Background: PPARGC1A produces PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α, but alternative splicing from exon 1b generates additional PGC-1α isoforms.

Results: Thermoregulatory thermogenesis is uncompromised in mice that lack PGC-1α but retain expression of slightly shorter forms of NT-PGC-1α.

Conclusion: NT-PGC-1α is sufficient to link β3-AR activation to the components of adaptive thermogenesis in adipose tissue.

Significance: NT-PGC-1α plays a crucial role in the physiological effects of PGC-1α.

Keywords: Adipose Tissue Metabolism, Adrenergic Receptor, Alternative Splicing, Tissue-specific Transcription Factors, Uncoupling Proteins, Adaptive Thermogenesis, PGC-1α

Abstract

PGC-1α is an inducible transcriptional coactivator that regulates cellular energy metabolism and adaptation to environmental and nutritional stimuli. In tissues expressing PGC-1α, alternative splicing produces a truncated protein (NT-PGC-1α) corresponding to the first 267 amino acids of PGC-1α. Brown adipose tissue also expresses two novel exon 1b-derived isoforms of PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α, which are 4 and 13 amino acids shorter in the N termini than canonical PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α, respectively. To evaluate the ability of NT-PGC-1α to substitute for PGC-1α and assess the isoform-specific role of NT-PGC-1α, adaptive thermogenic responses of adipose tissue were evaluated in mice lacking full-length PGC-1α (FL-PGC-1−/−) but expressing slightly shorter but functionally equivalent forms of NT-PGC-1α (NT-PGC-1α254). At room temperature, NT-PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α254 were produced from conventional exon 1a-derived transcripts in brown adipose tissue of wild type and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, respectively. However, cold exposure shifted transcription to exon 1b, increasing exon 1b-derived mRNA levels. The resulting transcriptional responses produced comparable increases in energy expenditure and maintenance of core body temperature in WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice. Moreover, treatment of the two genotypes with a selective β3-adrenergic receptor agonist produced similar increases in energy expenditure, mitochondrial DNA, and reductions in adiposity. Collectively, these findings illustrate that the transcriptional and physiological responses to sympathetic input are unabridged in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, and that NT-PGC-1α is sufficient to link β3-androgenic receptor activation to adaptive thermogenesis in adipose tissue. Furthermore, the transcriptional shift from exon 1a to 1b supports isoform-specific roles for NT-PGC-1α in basal and adaptive thermogenesis.

Introduction

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) plays a central role in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation (1–5), but it also regulates tissue-specific metabolic programs such as adaptive thermogenesis in brown fat (1), hepatic gluconeogenesis, metabolic response to starvation (6–8), and fiber type switching in muscle (9). In each of these cellular contexts, the function of PGC-1α is regulated by signaling inputs that increase transcription of the PGC-1α gene and activity of expressed protein. This allows PGC-1α to function as an inducible conduit that links environmental and nutritional stimuli to tissue-specific transcriptional programs of cellular adaptation.

Alternative splicing of PGC-1α between exons 6 and 7 produces an additional transcript that codes for a shorter isoform of the gene called NT-PGC-1α (10, 11). The expressed protein includes the first 267 amino acids of PGC-1α and three additional amino acids from the inserted intron. Cold-induced transcriptional activation of the PGC-1α gene produces a comparable increase in the mRNAs for PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α in adipose tissue (10). Both PGC-1α isoforms are transcriptionally active, but because the proteins are co-expressed, the specific role of NT-PGC-1α in the overall function of PGC-1α remains uncertain.

Mice lacking PGC-1α were produced by two groups using different targeting strategies (12, 13). Evaluation of their respective phenotypes revealed many similarities, but several interesting differences emerged with respect to brown fat morphology and thermogenic responses to cold. For example, in the null line produced by Lin et al. (12), the mice were cold-intolerant and their brown adipose tissue (BAT)4 exhibited abnormal accumulation of large lipid droplets. In contrast, the morphology of brown adipose tissue was essentially normal in the null line described by Leone et al. (13). Of particular interest was the finding that the mice were cold-sensitive for ∼2 weeks after weaning, whereas slightly older null mice (42–77 days of age) were cold-tolerant (13). The gene targeting strategy employed by Leone et al. (13) involved insertion of a targeting vector containing an exon 3 between exons 5 and 6 to create a coding region frameshift at the junction between exons 5 and 3. The frameshift generated a premature termination codon at amino acid 255, which effectively blocked expression of full-length PGC-1α (FL-PGC-1α). However, the question of whether these FL-PGC-1α−/− mice retained the ability to express a truncated PGC-1α protein from the imputed transcript was not established (13). We show here that the FL-PGC-1α−/− mice developed by Leone et al. (13) retain expression of a slightly shorter form of NT-PGC-1α protein (amino acids 1–254). At room temperature, expressed protein in BAT is produced from a conventional exon 1 (exon 1a)-derived transcript, whereas acute cold exposure shifts transcription to the recently identified alternative exon 1 (exon 1b), producing new exon 1b-derived transcripts (14). Using a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches, we show that NT-PGC-1α254 is functionally equivalent to NT-PGC-1α and that the cold-induced isoforms of NT-PGC-1α254 effectively couple β-adrenergic receptors to the in vivo components of adaptive thermogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All animal experiments were conducted according to procedures reviewed and approved by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee on the basis of guidelines established by the National Research Council, the Animal Welfare Act, and the Public Health Service Policy on the human care and use of laboratory animals. FL PGC-1α−/− mice (13) were obtained from Dr. Dan Kelly (Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute). All experiments were performed using 8- or 10-week-old male C57BL/6J mice that are homozygous for the wild type allele (WT) and FL-PGC-1α−/− genotype. For cold exposure experiments, WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice were singly housed and placed at 4 °C for 5 h. Core rectal temperature was measured at baseline and every 1 h over the 5-h period as described previously (15). Following the 5-h cold exposure, mice were rapidly euthanized, and tissues were harvested for RNA and protein isolation. To conduct metabolic phenotyping, eight WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice were provided a low fat (10 kcal % fat) diet (D12450B, Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) ad libitum for 2 weeks. Thereafter, mice were weighed, and their body composition was determined by NMR using a Bruker Mouse Minispec (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA) prior to transfer of the mice into indirect calorimetry chambers. After an overnight acclimation, oxygen consumption (VO2) was monitored at 18-min intervals for 7 days using a Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Physical activity was monitored using an OPTO-M3 sensor system while the mice were in the chamber. After 3 days in the chamber, mice were switched to the same low fat diet but formulated by Research Diets, Inc. (New Brunswick, NJ) to contain 0.001% CL316,243 as described previously (16), and oxygen consumption was continuously monitored for four additional days. Thereafter, body weight and composition were determined prior to harvest of brown and white adipose tissue. Energy expenditure was calculated as {VO2 × [3.815 + (1.232 × RQ)] × 4.187} and expressed as either kilojoules per hour per kilogram body weight or per kilogram fat free mass for analysis. In a separate cohort of age-matched WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, morphological remodeling of brown and white adipose tissue was assessed after consumption of the CL316,243-containing low fat diet for 6 days.

Plasmids

pcDNA3.1-NT-PGC-1α-HA has been described previously (10). NT-PGC-1α254 was cloned into pCR4Blunt-TOPO (Invitrogen) from BAT cDNA that was obtained by reverse transcription of mRNA isolated from FL-PGC-1α−/− mouse BAT using primers: forward, 5′-GGATCCAGGATGGCTTGGGACATGTGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCGAGTTAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTAGCCTCTATCTTCTTGAGCATGTTGCGAC-3′. Then, the BamHI/XhoI fragment containing NT-PGC-1α254 was subcloned to pcDNA3.1. Two additional exon 1b-derived isoforms (b and c) of NT-PGC-1α were cloned from BAT cDNA from WT or FL-PGC-1α−/− mouse using the primers described previously (14). pcDNA3.1-GAL4-ERRα-LBD, pSG51-mERRα, and pERRα-promoter luc were gifts from Dr. Natasha Kralli (Scripps Research Institute).

Real-time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center) and RNeasy kits (Qiagen). For quantitative RT-PCR analysis, 2 μg of RNA samples were reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) primers and M-MLVreverse transcriptase (Promega), and 10 ng of cDNA were used in quantitative PCR reactions in the presence of a fluorescent dye (Cybergreen, Takara) on a Smart Cycler (Cepheid) or Applied Biosystems 7900 (Applied Biosystems). Relative abundance of mRNA was normalized to that of cyclophilin mRNA. The following primers were used: for PGC-1α, 5′-TGCCATTGTTAAGACCGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTGGGGTCATTTGGTGAC-3′ (reverse); for NT-PGC-1α, 5′-GGTCACTGGAAGATATGGC-3′ (reverse); for NT-PGC-1α254, 5′-TATCTTCTTGAGCATGTTGCG-3′ (reverse); for Dio2, 5′-CAGTGTGGTGCACGTCTCCAATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGAACCAAAGTTGACCACCAG-3′ (reverse); for COXII, 5′-TGAAGACGTCCTCCACTCATGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCTGGGATGGCATCAGTT-3′ (reverse); for LCAD, 5′-GCCCGATGTTCTCATTCTGGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCTTGCCAGCTTTTTCCCAG-3′ (reverse). The primers for PGC-1α isoforms (a, b, c) (14), UCP1 (10), cyclophilin (10), CIDEA (17), Cox8b (18) were described previously.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

ChIP was conducted to examine the recruitment of NT-PGC-1α254 onto the UCP1 enhancer as described previously (10). In brief, 200 μg of the cross-linked nuclear BAT protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the N terminus of PGC-1α or anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Real-time PCR was used to quantify the amount of the Ucp1 enhancer immunoprecipitated with the protein. A non-targeting intragenic region of the UCP1 gene was amplified as a control genomic region. Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least three independent ChIP experiments.

Western Blot

Adipose tissues were homogenized under liquid nitrogen. Expression of PGC-1α isoforms were measured by Western blot using a monoclonal antibody directed against the N terminus of PGC-1α as described previously (10). β-Actin was from Abcam.

Immunocytochemistry

CHO-K1 cells were seeded on coverslips and transiently transfected with three different isoforms of NT-PGC-1α or NT-PGC-1α254 using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science). Cell fixation and immunocytochemistry were carried out as described previously (11). Briefly, the fixed cells were incubated with the blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum and 5% BSA in 1× PBS), followed by incubation with a 1:5000 diluted rabbit anti-HA antibody (Abcam) for 1 h. After washing with 1× PBS three times, cells were incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin secondary antibody for 0.5 h (Invitrogen). Cells were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). Subcellular localization was examined with a Plan-Neofluar 40×/0.85 numerical aperture NA objective on a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

COS-1 cells were transiently transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) with GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter gene (pGK), plasmids expressing GAL4-DBD-fused mouse PPARγ and ERRα-LBD, and plasmids pcDNA3.1/NT-PGC-1α-HA/NT-PGC-1α254-HA. For a luciferase reporter assay with full-length PPARγ and ERRα, (PPRE)3-TK-luc and pERRα-promoter luc were used, respectively. pRL-SV40 control plasmid expressing Renilla luciferase was used for normalization. The cells were treated with vehicle, BRL49653, or WY14693 24 h after transfection. Cells were harvested for luciferase assay 30 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was determined using a Promega Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega). The firefly luciferase activity was normalized with Renilla luciferase activity. Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least four independent experiments.

Analysis of Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Brown and white adipose tissues dissected from PBS-perfused mice were stained with 300 to 500 nm Mitotracker Red CMXROS (Invitrogen) in DMEM for 1 h at 37 °C as described previously (19). After washing with 1× PBS three times, tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h and imaged by Leica CTR 6500 confocal microscopy (Leica). For quantitative assessment of mitochondrial biogenesis, the ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear DNA was analyzed using quantitative RT-PCR (20). The primers for the NADH dehydrogenase subunit I were as follows: 5′-CCCATTCGCGTTATTCTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGTTGATCGTAACGGAAGC-3′ (reverse); and for the lipoprotein lipase, primers were as follows: 5′-GGATGGACGGTAAGAGTGATTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATCCAAGGGTAGCAGACAGGT-3′ (reverse).

RESULTS

Expression of Cold-inducible NT-PGC-1α Isoforms by FL-PGC-1α−/− Mice

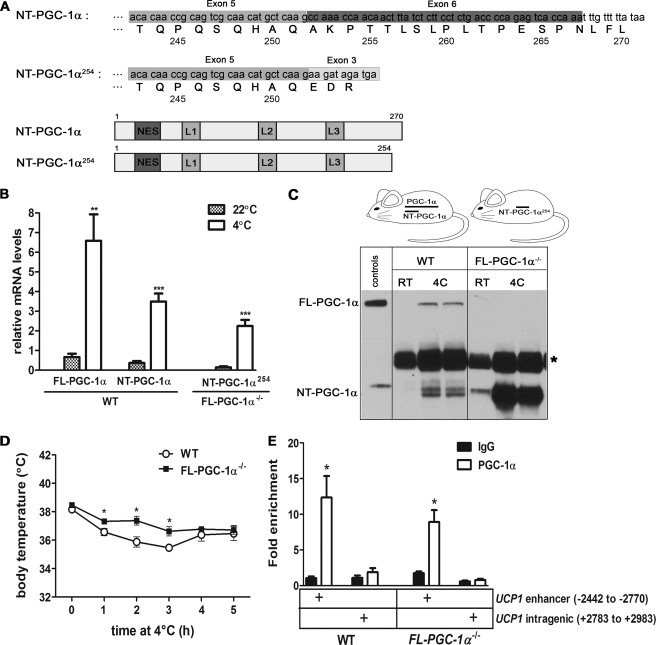

Various components of the phenotype of mice lacking PGC-1α were reported previously by two groups (12, 13). Lin et al. (12) employed homologous recombination/Cre-mediated excision of exons 3 to 5 of the PGC-1α gene, which would effectively disrupt expression of both full-length PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α, a 270-amino acid splice variant previously reported by our group (10, 11). Leone et al. (13) utilized a homologous recombination/insertion strategy to disrupt PGC-1α, resulting in an exon 3 duplication between exons 5 and 6. This insertion created a coding region frameshift at the junction between exons 5 and 3, generating a three codon addition and premature termination at amino acid 255 (Fig. 1A). The predicted PGC-1α protein (amino acids 1 to 254; NT-PGC-1α254) was not initially detected by Western blot analysis (13). However, the observed differences in specific components of the phenotype between the two lines raise the possibility that the PGC-1α−/− mice developed by Leone et al. (13) could be expressing NT-PGC-1α254, a slightly shorter but potentially bioactive form of naturally occurring NT-PGC-1α.

FIGURE 1.

The FL-PGC-1α−/− mice expressing a cold-inducible NT-PGC-1α254 are cold-tolerant. A, schematic diagram of NT-PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α254 mRNAs and proteins. B, quantitative real-time PCR analysis of full-length PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α mRNA in BAT from WT mice and NT-PGC-1α254 mRNA in BAT from FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, respectively, placed at room temperature (22 °C) or 4 °C for 5 h. Data represent mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. C, Western blot analysis of full-length PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α254 proteins in brown fat extracts from WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, respectively, placed at room temperature (RT; 22 °C) or 4 °C (4C) for 5 h. Asterisk represents nonspecific bands. Lysates containing full-length PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α were used as a positive control. D, body temperature of 10-week-old WT (n = 4) and FL-PGC-1α−/− (n = 4) mice exposed to cold (4 °C). Core body temperature was measured with a rectal thermometer every hour. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. E, recruitment of NT-PGC-1α254 onto the UCP1 enhancer in BAT. The amount of the UCP1 enhancer immunoprecipitated with IgG or PGC-1α antibody from WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− BAT was analyzed by quantitative PCR. A nonspecific intragenic region of the UCP1 gene was used as an additional negative control. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05.

To test for expression of a putative NT-PGC-1α254 transcript for PGC-1α−/− mice in Leone et al. (13), primers were designed to amplify the NT-PGC-1α254 transcript containing the exon 5–3 junction (Fig. 1A). In WT mice, PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α mRNA in BAT increase rapidly in response to cold and reach to peak levels within 5–6 h (10, 21). In BAT from the PGC-1α−/− mice of Leone et al. (13), NT-PGC-1α254 mRNA was readily detected at room temperature (22 °C) and increased by 16-fold after 5 h of cold exposure (Fig. 1B). Basal and cold-induced levels of NT-PGC-1α254 mRNA were slightly lower than NT-PGC-1α mRNA levels observed in WT mice (Fig. 1B), but the cold-induced induction of transcription was comparable between the genotypes (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the NT-PGC-1α254 transcript was translated into protein, Western blots were conducted using a N-terminally directed monoclonal PGC-1α antibody developed by our group (10). As reported previously, PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α were detected weakly in BAT from WT mice housed at room temperature but significantly increased by 5 h of cold exposure (Fig. 1C) (10). In contrast, NT-PGC-1α254 protein was abundant in BAT from PGC-1α−/− mice at room temperature and cold exposure produced a significant additional increase in expression of NT-PGC-1α254 (Fig. 1C). And as expected, the PGC-1α−/− mice from Leone et al. (13) did not express full-length PGC-1α at either temperature (Fig. 1C). Thus, our data confirm that the PGC-1α−/− mice from Leone et al. (13) express no full-length PGC-1α but reveal that the mice express a slightly shorter form of NT-PGC-1α (NT-PGC-1α254). Therefore, we have designated the mice developed by Leone et al. (13) as FL-PGC-1α−/− mice to denote the specific absence of full-length PGC-1α expression.

The PGC-1α−/− mice developed by Lin et al. (12) are cold-intolerant, and we have previously established that these mice express neither NT-PGC-1α nor PGC-1α (10). In contrast, the FL-PGC-1α−/− mice express NT-PGC-1α254 (Fig. 1) and although they are sensitive to cold for ∼2 weeks after weaning, mice tested after 6 weeks of age were cold-tolerant (13). To examine the temporal pattern and effectiveness of the adaptive thermogenic response in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, changes in core temperature were measured in 10-week-old FL-PGC-1α−/− mice housed at 4 °C during a 5-h period. Core body temperature was similar between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice at room temperature, and the FL-PGC-1α−/− mice actually maintained a higher body temperature than WT mice after exposure to cold (Fig. 1D). WT mice exhibited an initial drop of 2.7 °C within 3 h, whereas the mean decline in body temperature of FL-PGC-1α−/− mice was 1.85 °C (Fig. 1D). At the 4- and 5-h time points, WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice maintained similar core temperatures (Fig. 1D). As originally shown by Leone et al. (13), we found that induction of UCP1 expression in BAT did not differ between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (data not shown).

To examine the predicted recruitment of NT-PGC-1α254 to an established target gene promoter, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were employed using BAT from WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice after brief cold exposure, and NT-PGC-1α bound to the UCP1 enhancer (-2442 to −2270) containing cis-acting elements (e.g. PPRE and TRE) (10, 22, 23) was analyzed by quantitative PCR. A polyclonal antibody directed against the N terminus of PGC-1α efficiently immunoprecipitated PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α from WT BAT and NT-PGC-1α254 from FL-PGC-1α−/− BAT, respectively (supplemental Fig. S1). Fig. 1E shows that cold exposure produced a 6.6-fold increase in enrichment of PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α at the UCP1 enhancer (−2442 to −2270) over a non-targeting intrangenic region of UCP1 gene (+2783 to +2983) in WT BAT, indicating their specific recruitment to the UCP1 enhancer. Similarly, the enrichment of NT-PGC-1α254 at the UCP1 enhancer relative to a non-targeting region was 10.9-fold higher in BAT of FL-PGC-1α-KO after cold exposure. The relative amount of UCP1 enhancer immunoprecipitated with PGC-1α antibody from WT and FL-PGC-1α-KO BAT was 11.6- and 5.1-fold increased, respectively, when compared with IgG (Fig. 1E). The data show that NT-PGC-1α254 is efficiently and specifically recruited to the UCP1 enhancer in FL-PGC-1α−/− BAT.

Induction of Alternative Exon 1b-derived Isoforms of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α by Cold Exposure in BAT

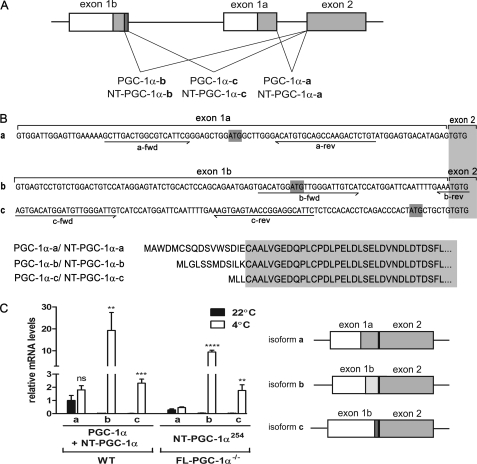

Recently, two novel PGC-1α transcripts (BB853729 and AW012094), reported in the murine expressed sequencing tag (EST) databases at NCBI, have been characterized and found to be expressed in a tissue-specific manner and induced by cold and exercise in mouse BAT and skeletal muscle, respectively (14). The PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c transcripts are derived by alternative splicing of a novel exon 1 (designated exon 1b) at two different 5′ splice sites to the canonical exon 2. The alternative first exon, which is also conserved in human, is located 13.7 kb upstream from the canonical exon 1 (designated exon 1a) of the PGC-1α gene (Fig. 2A) (14, 24, 25). The N-terminal 16 amino acids in PGC-1α differ from those of PGC-1α-b or PGC-1α-c with 4 and 13 amino acids shorter N termini of PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c than that of PGC-1α (PGC-1α-a), respectively (Fig. 2B) (14).

FIGURE 2.

Cold-inducible exon 1b-derived isoforms of PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α. A, schematic structure of the 5′ region of the murine PGC-1α gene. The schematic structure was slightly adapted from the Miura et al. (14). Boxes indicate exons, and lines indicate introns. The coding regions and untranslated regions are shown in gray and white, respectively. An alternative exon 1b and a canonical exon 1a are spliced to the common exon 2 by three different splicing events. Three different isoforms of NT-PGC-1α are also produced with combination of alternative 3′ splicing at the intron between exons 6 and 7. B, mRNA and protein sequences of exon 1a- and exon 1b-derived isoforms of PGC-1α/NT-PGC-1α. The 5′ region sequences of exon 1a- and exon 1b-derived transcripts are shown with isoform-specific primers underlined (top). Amino acid sequences of exon 1a- and exon 1b-derived isoforms. The gray box represents the common coding sequences of exon 2 (bottom). C, cold induction of exon 1b-derived transcripts in BAT. Using isoform-specific primers, quantitative real-time PCR analysis was carried out to examine expression of exon 1a- and exon 1b-derived transcripts in BAT from WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, respectively. Mice were placed at room temperature (22 °C) or cold-exposed for 5 h. Data represent mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. rev, reverse; fwd, forward.

The findings of two additional exon 1b-derived transcripts suggest that the molecular mechanism by which cold induces PGC-1α expression in BAT is more complex than proposed previously. NT-PGC-1α is generated by alternative 3′ splicing at the intron between exons 6 and 7 (10). Thus, the single PGC-1α gene has the potential to produce six different transcripts (e.g. PGC-1α-a, -b, and -c and NT-PGC-1α-a, -b, and -c). To examine this possibility in greater detail, we analyzed basal and 5-h cold-induced expression of three different isoforms (a, b, c) in BAT of WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice using the isoform-specific primers previously described (Fig. 2B) (14). It should be noted that the isoform-specific PCR products are amplified from both PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α transcripts by these primers (named total PGC-1α). As previously reported, basal mRNA levels of total PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c in BAT of WT mice were very low when compared with that of total PGC-1α-a (Fig. 2C). However, total PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c mRNA were markedly induced (∼2000-fold and ∼416-fold, respectively) after 5 h of cold exposure, whereas the increase in total PGC-1α-a mRNA did not differ from basal levels (Fig. 2C). Similarly, NT-PGC-1α254-a mRNA was the dominant transcript in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice housed at RT, whereas after cold exposure only the mRNAs derived from exon 1b (NT-PGC-1α254-b and NT-PGC-1α254-c) were increased significantly (Fig. 2C). The quantitative PCR data demonstrate that novel exon 1b-derived transcripts (b and c) are preferentially induced by cold in both WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, whereas the canonical exon 1a-derived mRNA produces the primary mRNA species expressed under basal conditions (Fig. 1C).

NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c Are Functional Transcriptional Coactivators

Miura et al. (14) demonstrated that the two exon 1b-derived isoforms of PGC-1α, PGC-1α-b, and PGC-1α-c, are functionally active and induce PPAR-dependent transcription to an extent comparable with PGC-1α-a. It was also shown that overexpression of PGC-1α-b or PGC-1α-c in skeletal muscle preferentially up-regulated genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation (14). To examine whether NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c transcripts produce functional coactivators and compare their functional properties relative to the originally described NT-PGC-1α-a isoform (10), the respective cDNAs of NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c were cloned from a murine BAT cDNA library into an expression vector. The sequencing of PCR products confirmed that NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c cDNA had the unique exon 1b sequences, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2B. In addition, the exon 2-downstream sequences were identical in all isoforms.

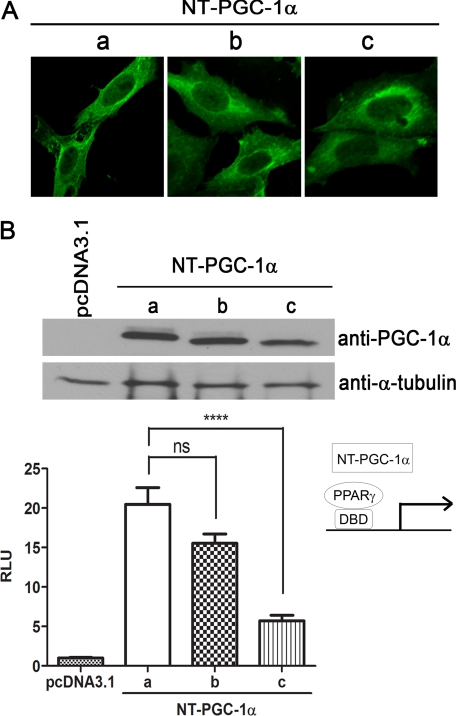

NT-PGC-1α-a, -b, and -c were expressed in CHO-K1 cells to compare their subcellular distributions. Full-length PGC-1α is a nuclear protein, but the lack of C-terminal nuclear localization signals leads NT-PGC-1α-a to shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm, residing primarily in the cytoplasm (11). Comparison of the subcellular distributions of NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c by confocal microscopy showed that they, like NT-PGC-1α-a, were found primarily in the cytosol (Fig. 3A). Treatment of cells with Bt2cAMP, which rapidly increases the nuclear concentration of NT-PGC-1α-a (11), also increased nuclear content of NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c (data not shown). To assess the transcriptional activity of the respective isoforms, their ability to bind and transactivate PPARγ was compared by co-expressing a GAL4-DNA binding domain-fused PPARγ, a GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter, and the respective NT-PGC-1α-a, -b, and -c isoforms. The upper panel of Fig. 3B shows that the NT-PGC-1α isoforms were expressed at comparable levels, and the lower panel illustrates that co-activation of PPARγ by NT-PGC-1α-a (∼20-fold) and NT-PGC-1α-b (∼15-fold) did not differ. However, the 5-fold increase in co-activation of PPARγ by NT-PGC-1α-c was significantly lower than that of the other isoforms (Fig. 3B). This may be in part due to its slightly lower expression level. Although not shown, co-activation of other nuclear receptors followed a similar pattern, demonstrating that NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c physically interact with and co-activate nuclear receptors.

FIGURE 3.

Exon 1b-derived NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c are functional transcriptional coactivators. A, identical localization of NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α-c to NT-PGC-1α-a. Three different isoforms of NT-PGC-1α-HA were expressed in CHO-K1 cells, and their localization was analyzed by immunocytochemistry using anti-HA antibody. B, transcriptional coactivation assay. pcDNA3.1 and NT-PGC-1α-HA (a, b, c) were co-transfected in COS-1 cells with a GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter, GAL4-PPARγ, and a Renilla luciferase reporter, respectively. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with BRL49653. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection, and the relative luciferase units (RLU) were normalized using Renilla luciferase activity. Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least five independent experiments. ****, p < 0.0001 and ns, not significant. DBD represents DNA-binding domain. The same lysates were used for protein expression of three different isofoms of NT-PGC-1α-HA using anti-PGC-1α antibody. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luciferase units.

Functional Properties of NT-PGC-1α254 Isoforms Expressed in FL-PGC-1α−/− Mice

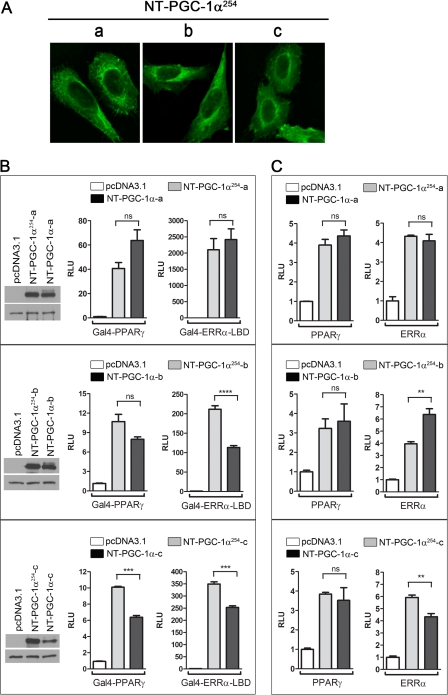

Figs. 1 and 2 establish that FL-PGC-1α−/− mice retain expression of cold-inducible NT-PGC-1α254 isoforms in BAT, but it is unclear whether these slightly shorter isoforms retain the full functionality of the native NT-PGC-1α isoforms. To address this question, cDNAs of the PGC-1α254 isoforms were cloned from a FL-PGC-1α−/− BAT cDNA library, expressed in CHO cells, and compared with the native PGC-1α isoforms with respect to subcellular localization and co-activation of nuclear receptors. As reported previously for NT-PGC-1α-a (10, 11) and shown for NT-PGC-1α-b and -c (Fig. 3A), the subcellular localization of all three isoforms of NT-PGC-1α254 was cytoplasmic (Fig. 4A). A side-by-side comparison of coactivation of Gal4-PPARγ and Gal4-ERRα-LBD by NT-PGC-1α-a versus NT-PGC-1α254-a showed comparable co-activation of each nuclear receptor by the two proteins (Fig. 4B). In the context of PPARγ and ERRα, NT-PGC-1α254-a coactivated PPARγ and ERRα to levels similar to NT-PGC-1α-a (Fig. 4C). Likewise, NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α254-b showed comparable co-activation of Gal4-PPARγ and PPARγ (Fig. 4, B and C). In contrast, a slightly different pattern emerged from the comparison of NT-PGC-1α-b and NT-PGC-1α254-b in the coactivation of Gal4-ERRα-LBD and ERRα. NT-PGC-1α254-b was 2-fold better than the native NT-PGC-1α-b in activating Gal4-ERRα-LBD, whereas NT-PGC-1α-b was slightly more effective than NT-PGC-1α254-b in transactivation of ERRα (Fig. 4, B and C). Transactivation of Gal4-fused or full-length nuclear receptors by NT-PGC-1α254-c was greater than NT-PGC-1α-c, but this may have been due to the slightly higher expression of NT-PGC-1α254-c (Fig. 4B, left panel). Together, these results indicate that the ability of the NT-PGC-1α254 isoforms to interact with and co-activate nuclear receptors is intact and similar to the properties of native NT-PGC-1α isoforms.

FIGURE 4.

Three isoforms of NT-PGC-1α254 retain the functional properties of NT-PGC-1α. A, localization of three different isoforms of NT-PGC-1α254. NT-PGC-1α254-HA (a, b, and c) were expressed in CHO-K1 cells, and their localization was analyzed by immunocytochemistry using anti-HA antibody. B, transcriptional coactivation assay. Each isoform of NT-PGC-1α254-HA and NT-PGC-1α-HA was co-transfected in COS-1 cells with a GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter, GAL4-PPARγ, or GAL4-ERRα-LBD. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection, and the relative luciferase units (RLU) were normalized using Renilla luciferase activity. Data represent mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. The same lysates were used for protein expression of each isoform of NT-PGC-1α254-HA and NT-PGC-1α-HA using anti-PGC-1α antibody. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. C, transcriptional coactivation assays were performed as described above. PPARγ/(PPRE)3-TK-luc and ERR/pERRα-promoter luc were used, respectively. ns, not significant.

In Vivo Functionality of NT-PGC-1α254 Isoforms Expressed in FL-PGC-1α−/− Mice

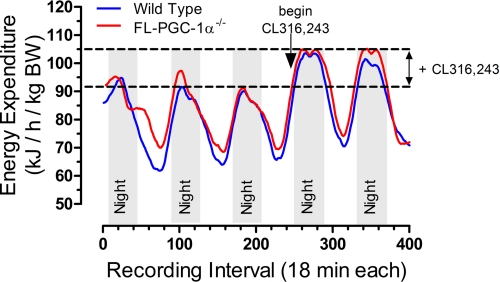

Fig. 4 demonstrates that the NT-PGC-1α254 isoforms are fully functional in their ability to transactivate nuclear receptors, whereas Figs. 1 and 2 show that FL-PGC-1α−/− mice are cold-tolerant and express inducible NT-PGC-1α254 isoforms in BAT. Although data are not shown, we have also detected expression of NT-PGC-1α254 in other tissues so the contribution of PGC-1α254 expression in BAT to the overall thermogenic response of FL-PGC-1α−/− mice remains uncertain. To address this question and compare the relative contribution of adipose tissue to the increase in energy expenditure produced by SNS stimulation, we used indirect calorimetry to evaluate changes in O2 consumption in WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice treated with a selective β3-adrenergic agonist, CL316,243. This strategy takes advantage of the adipose tissue-specific expression of the β3-adrenergic receptor to evaluate how the expression of NT-PGC-1α254 isoforms in the absence of FL-PGC-1α affects the response of adipose tissue to a sympathomimetic agonist. This was accomplished by careful metabolic phenotyping of the respective genotypes during a 3-day pre-experimental period prior to introduction of the agonist, followed by careful measurement of the changes in their metabolic phenotype after introduction of the agonist. With this approach, the agonist-dependent changes in the responses provide pairwise comparisons of the contribution of adipose tissue to various components of energy balance between the genotypes. In the pre-experimental period prior to introduction of the agonist, body weights, adiposity, and food intake did not differ between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Table 1). Energy expenditure (EE), expressed either per unit body weight (BW) or fat free mass was ∼3% higher in FL-PGC-1α−/− compared with WT mice, but this difference was significant because of the higher precision of measurements made over the 3-day period (Table 1). In contrast, voluntary activity was significantly lower in FL-PGC-1α−/− compared with WT mice (Table 1). The 4-day treatment with the β3-adrenergic receptor (AR) agonist produced no change in BW or food intake in either genotype, but it did produce a comparable reduction in adiposity in WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Table 1). The initial introduction of β3-AR agonist was the beginning of the dark cycle on day 3. Fig. 5 illustrates that it immediately increased EE from a nighttime zenith of ∼90 kJ/h/kg BW to ∼105 kJ/h kg BW in both WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice. The β3-AR agonist also produced a modest increase in daytime EE in both genotypes (Fig. 5), and a comparable 11–16% increase in total 24 h EE in both genotypes (Table 1). In contrast, CL316,243 decreased voluntary activity by ∼40% in WT mice and ∼25% in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Table 1). Collectively, these data illustrate that the energy balance phenotype (BW, energy intake, adiposity) and the ability of adipose tissue to increase EE and mobilize fat is completely intact and uncompromised in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice.

TABLE 1.

Responses of wild type and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice to treatment with vehicle or β3-adrenergic agonist (CL316,243)

Male C57BL/6J mice (WT) or FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (13) were provided a low fat diet (10 kcal % fat) for 2 weeks beginning at 8 weeks of age and then switched to the same diet formulated to contain CL316,243 as described under “Materials and Methods.”

| Response variable | WT micea |

FL-PGC-1α−/− mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CL316,243 | Control | CL316,243 | |

| Body weight (g) | 24.9 ± 0.6* | 24.7 ± 0.8* | 23.4 ± 0.7* | 23.4 ± 1.0* |

| Food consumption (g/day) | 3.02 ± 0.10* | 3.08 ± 0.32* | 2.89 ± 0.08* | 2.68 ± 0.10* |

| % adiposity (g fat mass/g of body weight × 100) | 14.9 ± 0.9* | 11.9 ± 0.9** | 13.4 ± 1.1* | 10.0 ± 0.9** |

| Total energy expenditure (kJ/h/kg of body weight) | 79 ± 0.8* | 88 ± 1.1** | 82 ± 0.7*** | 91 ± 1.0** |

| Total energy expenditure (kJ/h/kg of fat free mass) | 102 ± 0.9* | 115 ± 0.9** | 105 ± 0.8*** | 122 ± 0.8**** |

| Total activity (arbitrary units) | 877 ± 46* | 625 ± 38** | 556 ± 28*** | 444 ± 25*** |

a Body weight and composition were determined prior to transfer of mice into the metabolic chambers and 7 days later. Group means for total energy expenditure per unit fat free mass (FFM) and per unit BW, and total voluntary activity were calculated for the 3-day pre-experimental period and for the 4 days after introduction of CL316,243. Energy expenditure was calculated from repeated measures of O2 consumption made at 18-min intervals for the 3-day pre-experimental period (n = 216/mouse) and for 4 days (n = 288) after introduction of CL316,243. Group means were compared using a one-way analysis of variance and means annotated with different superscripts differ at p < 0.05.

FIGURE 5.

Change in energy expenditure of FL-PGC-1α−/− mice after treatment with selective β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. WT (n = 8) and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (n = 8) were provided a low fat diet for 2 weeks prior to measurement of O2 consumption for a total of 5 days, the first three days while consuming the low fat diet containing vehicle followed by 2 days of consuming the same diet containing 0.001% CL316,243, a selective β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Energy expenditure was calculated as described under “Materials and Methods” and expressed per unit body weight (BW) because weight and body composition did not differ between the genotypes.

Remodeling of Adipose Tissue in FL-PGC-1α−/− Mice by Activation of β3-AR Signaling

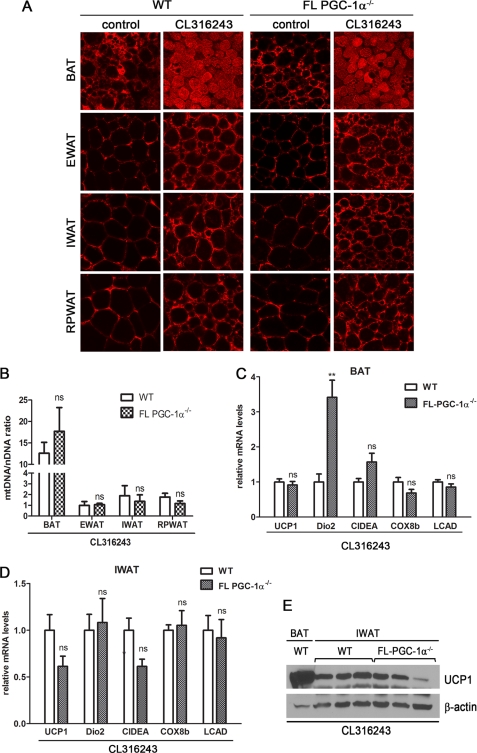

Prolonged sympathetic stimulation of adipose tissue, as produced by cold exposure or treatment with β3-AR agonists, induces the transcriptional program of adaptive thermogenesis in BAT and WAT and induces extensive remodeling of adipocyte morphology (19, 26–29). The β3-AR-dependent remodeling of adipose tissue included a reduction in adipocyte cell size, a decrease in lipid droplet size, and increase in the number of multilocular adipocytes. These changes in cell morphology occurred across all adipose tissue depots, and the responses did not differ between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Fig. 6A). The agonist-dependent increase in multilocular adipocytes was correlated with an increase in mitochondrial staining among the depots of both genotypes (Fig. 6A). At the molecular level, the morphological remodeling is associated with induction of mitochondrial biogenesis and expression of thermogenic and brown adipocyte-specific genes (e.g. UCP1, Dio2, CIDEA, and Elovl3). The ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear DNA across all CL316,243-treated depots of both genotypes was similar (Fig. 6B), and relative to EWAT, the ratio was 10- to 20-fold higher in BAT. CL316,243-induced mitochondrial density in BAT was comparable between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Fig. 6B), and the expression levels of mitochondrial genes were comparable between genotypes (Fig. 6C). The one notable exception was the ∼3.3-fold higher type 2 deiodinase (Dio2) mRNA in FL-PGC-1α−/− compared with WT mice (Fig. 6C). Among the WAT depots, CL316,243-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in EWAT, IWAT, and RPWAT was comparable between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Fig. 6B). Examination of the transcriptional responses to the agonist in IWAT revealed comparable increases in UCP1, Dio2, CIDEA, COX8b, and LCAD mRNAs from the two genotypes (Fig. 6D). UCP1 mRNA is highly induced by CL316,243 in IWAT, but to a lesser degree in EWAT and RPWAT of C57BL/B6 mice (27, 30). The significance of this response to the remodeling of WAT in the present study is shown in Fig. 6E, where the CL316,243-dependent induction of UCP1 produced protein levels in IWAT that were within the range of the levels expressed in BAT (Fig. 6E). In addition, Fig. 6E shows that the agonist produced comparable increases in IWAT UCP1 expression in WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice. Together, these data show that β3-AR-dependent morphological and transcriptional remodeling of adipose tissue was uncompromised in brown and white adipose tissue of FL-PGC-1α−/− mice.

FIGURE 6.

Morphological and transcriptional remodeling of adipose tissue in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice after treatment with selective β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. A, CL316,243-mediated induction of morphological changes and mitochondrial biogenesis in adipose tissue. Brown and white adipose tissues of wild-type (n = 4) and FL-PGC-1α−/− (n = 4) mice given the low fat diet (LF) (control) or LF+CL diet for 6 days were stained with Mitotracker Red and imaged by confocal microscopy. B, quantitative analysis of mitochondrial biogenesis. The ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear DNA was analyzed in BAT, EWAT, IWAT, and RPWAT from WT (n = 8) and FL-PGC-1α−/− (n = 8) mice given the LF+CL diet for 4 days. C and D, quantitative real time PCR analysis of gene expression in BAT and IWAT from WT (n = 8) and FL-PGC-1α−/− (n = 8) mice given the LF+CL diet for 4 days, respectively. Data represent mean ± S.E. E, CL316,243-mediated induction of UCP1 protein in IWAT. Immunoblotting of UCP1 protein in IWAT from WT (n = 3) and FL-PGC-1α−/− (n = 3) mice given the LF+CL diet for 4 days. The BAT lysates from WT mice given the LF+CL diet were used as a positive control. β-Actin was used as a control for equal loading of the samples. ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The PGC-1α gene was originally thought to produce a single protein, but recent studies have established that alternative RNA splicing generates multiple mRNAs and proteins (10, 11, 14, 31). For example, alternative splicing of PGC-1α between exons 6 and 7 generates a transcript with an in-frame stop codon and a truncated (270 amino acids) N-terminal isoform of PGC-1α that efficiently co-activates many genes regulated by full length PGC-1α (10, 11). Additional splice variants of PGC-1α are generated by alternative splicing of a novel exon 1b at two different 5′ splice sites to exon 2, producing transcripts for PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c which are translated into functional proteins that are 4 and 13 amino acids shorter in their N termini than canonical PGC-1α-a (14, 31). Of particular interest is the tissue-specific regulation of exon 1b-derived PGC-1α isofoms. For example, cold or exercise preferentially increases alternative exon 1b-derived PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c mRNA in BAT and muscle, whereas fasting in liver produces a selective increase in exon 1a-derived PGC-1α-a mRNA (14). We report for the first time that the alternative first exon giving rise to PGC-1α-b and -c isoforms in BAT functions in tandem with alternative splicing between exons 6 and 7 to produce the corresponding transcripts for NT-PGC-1α-b and -c. In practice, we found that in mice housed at 22 °C (e.g. basal conditions) transcription of PGC-1α in BAT occurs primarily from exon 1a, producing fairly equivalent levels of PGC-1α-a and NT-PGC-1α-a mRNAs. However, activation of PGC-1α by cold exposure shifts transcription to exon 1b, with PGC-1α-b, -c and NT-PGC-1α-b, -c becoming the primary transcripts produced from the gene. Thus, our findings extend the observations of Miura et al. (32), and show that the exon 1a to 1b switching produced by cold exposure in BAT produces not only PGC-1α-b and -c mRNA, but also a corresponding increase in expression of the NT-PGC-1α-b and -c isoforms. Thus, the molecular mechanisms through which environmental and nutritional stimuli regulate PGC-1α gene expression are significantly more complex than originally appreciated.

Transcriptional activation of PGC-1α involves cAMP-dependent activation of ATF2, increased binding of ATF2 to a cAMP-response element in the promoter (1, 33–35), and recruitment of additional transcription factors (CREB and C/EBPβ) to the CRE in the PGC-1α promoter (36). The exon 1b promoter also contains CRE sequences, a variant and a palindromic (antisense) CRE (24), but it is unclear why transcription shifts from exon 1a to 1b after sympathetic stimulation of BAT. The biological significance of the exon 1b-derived isoforms is also unclear. An initial in vitro assessment of transactivation efficacy of the three NT-PGC-1α isoforms revealed subtle differences but no obvious evidence of distinct differences between the exon 1a- and 1b-derived isoforms.

A more fundamental but as yet unanswered question is: Relative to the PGC-1α isoforms, what are the specific functions of the corresponding NT-PGC-1α isoforms and do they have tissue-specific roles. We have addressed this question in the present report through a loss of function approach after finding that the gene targeting strategy used to disrupt in vivo expression of PGC-1α by Leone et al. (37) effectively eliminated expression of full length PGC-1α, but the mice unexpectedly retained expression of 3 slightly shorter isoforms that were transcribed from the altered PGC-1α gene. We have denoted these shorter isoforms of NT-PGC-1α as NT-PGC-1α254-a, -b, and -c. These studies began with the hypothesis that the unique phenotype of the FL-PGC-1α−/− mice of Leone et al. (37) was due to expression of a shorter but functional form of NT-PGC-1α that was able to fully or partially substitute for the missing full length PGC-1α. We have utilized the retention of NT-PGC-1α254 expression in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice to test its ability to link β3-adrenergic receptor activation in adipose tissue to the transcriptional, morphological, and physiological components of adaptive thermogenesis. More careful examination of the induction of NT-PGC-1α254 in BAT showed that cold exposure shifted transcription from exon 1a to 1b and the increase in NT-PGC-1α254 mRNA was primarily due to increased expression of NT-PGC-1α254-b and to a lesser extent NT-PGC-1α254-c (Fig. 2).

The exon 1a to 1b switching after gene activation was comparable between WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice, but surprisingly, basal and cold-induced NT-PGC-1α254 protein expression was significantly higher than NT-PGC-1α expression in WT mice. In the absence of higher mRNA, this observation suggests potential differences in stability or the interesting possibility that full-length PGC-1α may regulate the levels of NT-PGC-1α at the post-transcriptional level. Exogenous expression of NT-PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α254 under a CMV promoter produced comparable levels of proteins, suggesting no difference in protein stability itself. The higher expression may be indicative of a mechanism to compensate for the absence of full length PGC-1α, but it may also reflect tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms since NT-PGC-1α254 and NT-PGC-1α expression in the CNS of FL-PGC-1α−/− and WT mice was comparable (data not shown). Further experiments will be required to address the underlying causes and significance of these tissue-specific differences in NT-PGC-1α254 expression.

In contrast to the observed cold intolerance of mice lacking both NT-PGC-1α and full length PGC-1α (12), we found that FL-PGC-1α−/− mice were better able to maintain core body temperature than WT mice after cold exposure, and that NT-PGC-1α254 in FL-PGC-1α−/− BAT was efficiently recruited to the UCP1 enhancer in response to cold (Fig. 1). The initial thermogenic response to cold involves a SNS- and cAMP-dependent increase in fatty acid mobilization and activation of existing UCP1, while chronic increases in cAMP expand the thermogenic capacity of BAT and WAT by activating the PGC-1α-dependent transcriptional programs of adaptive thermogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis. The transcriptional responses in adipose to chronic β3-AR activation were uncompromised in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Fig. 6), and produced a 20–25% decrease in adiposity in both WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Table 1). In addition, the β3-AR agonist-induced increase in EE was comparable in WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice (Table 1 and Fig. 5). Two design features make it possible to attribute the observed 14% increase in EE to adaptive thermogenic responses in adipose tissue. First, measurement of in vivo O2 consumption in each mouse prior to and after introduction of the β3-AR agonist creates a paired design by allowing each animal to serve as its own control. This design strategy effectively isolates within-group variation of animals from the variance term used to test for genotypic differences, and focuses on differences in responses of individuals within each genotype to the agonist. In addition, because β3-AR expression is limited to adipose tissue, the increase in EE after introduction of the β3-AR-selective agonist effectively defines and compares baseline thermogenic capacity of adipose tissue (BAT and WAT) in the two lines. These data demonstrate that the uninduced thermogenic capacity of adipose tissue in WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice is indistinguishable (Fig. 5). Extending the comparison to the overall metabolic phenotype of WT and FL-PGC-1α−/− mice supports the view that overall energy homeostasis, adiposity, and the adaptive thermogenic capacity of adipose tissue were not compromised by the absence of full length PGC-1α in FL-PGC-1α−/− mice. Thus, these findings establish that NT-PGC-1α alone is sufficient for linking β-adrenergic signaling to the transcriptional remodeling of adipose tissue. However, our findings do not exclude the possibility that NT-PGC-1α and PGC-1α function interchangeably in this role. Addressing this question and establishing that NT-PGC-1α is both sufficient and necessary in this tissue-specific role will require an in vivo model that selectively disrupts NT-PGC-1α while retaining expression of full length PGC-1α. In practice, this distinction may be somewhat academic, given that the isoforms of PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α are both co-expressed and co-induced in adipose tissue after cold exposure. In contrast to adipose tissue, the role of NT-PGC-1α may be less significant in other tissues such as the brain, where the phenotype of FL-PGC-1α−/− and the complete PGC-1α−/− mice of Lin et al. (12) was more similar. We have shown that brain expresses both PGC-1α and NT-PGC-1α (10), but the physiological significance of NT-PGC-1α in the brain remains undefined. Thus, although the focus of the present report was on adipose tissue, our findings demonstrate the potential utility of FL-PGC-1α−/− mice as a unique new model to investigate the in vivo functions of NT-PGC-1α in other tissues where it may be more or less important than adipose tissue.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Dan Kelly and Natasha Kralli for providing FL-PGC-1α−/− mice and pcDNA3.1-GAL4-ERRα-LBD, pSG51-mERRα, and pERRα-promoter luc, respectively. We also thank Dr. Leslie Kozak, Dr. Dan Kelly, and Teresa Leone for invaluable input. We thank Anik Boudreau, Eric Plaisance, Amanda Laque, Nancy Van, Manda Orgeron, and David Burk for technical contributions and advice. We thank Anne Gooch for excellent administrative support.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 DK 074772 (to T. W. G.) and P20-RR021945 (to T. W. G. and J. S. C.). This work was also supported by PBRC Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NORC) Pilot and Feasibility Grant 1P30 DK072476 (to JSC). This work used Cell Biology & Bioimaging and Genomics core facilities, which are supported in part by COBRE (National Institutes of Health Grant P20-RR021945) and NORC (National Institutes of Health 1P30-DK072476) center grants from the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- β3-AR

- β3-androgenic receptor

- Bt2cAMP

- dibutyryl cyclic AMP

- EE

- energy expenditure

- BW

- body weight

- LBD

- ligand binding domain

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PPRE

- PPAR response element

- EWAT

- epididymal white adipose tissue

- IWAT

- inguinal white adipose tissue

- RPWAT

- retroperitoneal white adipose tissue

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- ERR

- estrogen-related receptor

- LCAD

- long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Puigserver P., Wu Z., Park C. W., Graves R., Wright M., Spiegelman B. M. (1998) A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92, 829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu Z., Puigserver P., Andersson U., Zhang C., Adelmant G., Mootha V., Troy A., Cinti S., Lowell B., Scarpulla R. C., Spiegelman B. M. (1999) Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lehman J. J., Barger P. M., Kovacs A., Saffitz J. E., Medeiros D. M., Kelly D. P. (2000) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 847–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mootha V. K., Lindgren C. M., Eriksson K. F., Subramanian A., Sihag S., Lehar J., Puigserver P., Carlsson E., Ridderstråle M., Laurila E., Houstis N., Daly M. J., Patterson N., Mesirov J. P., Golub T. R., Tamayo P., Spiegelman B., Lander E. S., Hirschhorn J. N., Altshuler D., Groop L. C. (2003) PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately down-regulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 34, 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schreiber S. N., Emter R., Hock M. B., Knutti D., Cardenas J., Podvinec M., Oakeley E. J., Kralli A. (2004) The estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα) functions in PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6472–6477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herzig S., Long F., Jhala U. S., Hedrick S., Quinn R., Bauer A., Rudolph D., Schutz G., Yoon C., Puigserver P., Spiegelman B., Montminy M. (2001) CREB regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis through the coactivator PGC-1. Nature 413, 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yoon J. C., Puigserver P., Chen G., Donovan J., Wu Z., Rhee J., Adelmant G., Stafford J., Kahn C. R., Granner D. K., Newgard C. B., Spiegelman B. M. (2001) Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature 413, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rhee J., Inoue Y., Yoon J. C., Puigserver P., Fan M., Gonzalez F. J., Spiegelman B. M. (2003) Regulation of hepatic fasting response by PPARγ coactivator-1α (PGC-1): Requirement for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α in gluconeogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4012–4017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin J., Wu H., Tarr P. T., Zhang C. Y., Wu Z., Boss O., Michael L. F., Puigserver P., Isotani E., Olson E. N., Lowell B. B., Bassel-Duby R., Spiegelman B. M. (2002) Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 α drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibers. Nature 418, 797–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang Y., Huypens P., Adamson A. W., Chang J. S., Henagan T. M., Boudreau A., Lenard N. R., Burk D., Klein J., Perwitz N., Shin J., Fasshauer M., Kralli A., Gettys T. W. (2009) Alternative mRNA splicing produces a novel biologically active short isoform of PGC-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32813–32826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang J. S., Huypens P., Zhang Y., Black C., Kralli A., Gettys T. W. (2010) Regulation of NT-PGC-1α subcellular localization and function by protein kinase A-dependent modulation of nuclear export by CRM1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18039–18050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin J., Wu P. H., Tarr P. T., Lindenberg K. S., St-Pierre J., Zhang C. Y., Mootha V. K., Jäger S., Vianna C. R., Reznick R. M., Cui L., Manieri M., Donovan M. X., Wu Z., Cooper M. P., Fan M. C., Rohas L. M., Zavacki A. M., Cinti S., Shulman G. I., Lowell B. B., Krainc D., Spiegelman B. M. (2004) Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1α null mice. Cell 119, 121–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leone T. C., Lehman J. J., Finck B. N., Schaeffer P. J., Wende A. R., Boudina S., Courtois M., Wozniak D. F., Sambandam N., Bernal-Mizrachi C., Chen Z., Holloszy J. O., Medeiros D. M., Schmidt R. E., Saffitz J. E., Abel E. D., Semenkovich C. F., Kelly D. P. (2005) PGC-1α deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: Muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control, and hepatic steatosis. PLoS Biol. 3, e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miura S., Kai Y., Kamei Y., Ezaki O. (2008) Isoform-specific increases in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) mRNA in response to β2-adrenergic receptor activation and exercise. Endocrinology 149, 4527–4533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hasek B. E., Stewart L. K., Henagan T. M., Boudreau A., Lenard N. R., Black C., Shin J., Huypens P., Malloy V. L., Plaisance E. P., Krajcik R. A., Orentreich N., Gettys T. W. (2010) Dietary methionine restriction enhances metabolic flexibility and increases uncoupled respiration in both fed and fasted states. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 299, R728–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Surwit R. S., Feinglos M. N., Rodin J., Sutherland A., Petro A. E., Opara E. C., Kuhn C. M., Rebuffé-Scrive M. (1995) Differential effects of fat and sucrose on the development of obesity and diabetes in C57BL/6J and A/J mice. Metabolism 44, 645–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Uldry M., Yang W., St-Pierre J., Lin J., Seale P., Spiegelman B. M. (2006) Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 3, 333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Villena J. A., Hock M. B., Chang W. Y., Barcas J. E., Giguère V., Kralli A. (2007) Orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor α is essential for adaptive thermogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1418–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Granneman J. G., Li P., Zhu Z., Lu Y. (2005) Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue I: Effects of β3-adrenergic receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 289, E608–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Medeiros D. M. (2008) Assessing mitochondria biogenesis. Methods 46, 288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coulter A. A., Bearden C. M., Liu X., Koza R. A., Kozak L. P. (2003) Dietary fat interacts with QTLs controlling induction of Pgc-1 α and Ucp1 during conversion of white to brown fat. Physiol. Genomics 14, 139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sears I. B., MacGinnitie M. A., Kovacs L. G., Graves R. A. (1996) Differentiation-dependent expression of the brown adipocyte uncoupling protein gene: Regulation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 3410–3419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rabelo R., Schifman A., Rubio A., Sheng X., Silva J. E. (1995) Delineation of thyroid hormone-responsive sequences within a critical enhancer in the rat uncoupling protein gene. Endocrinology 136, 1003–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshioka T., Inagaki K., Noguchi T., Sakai M., Ogawa W., Hosooka T., Iguchi H., Watanabe E., Matsuki Y., Hiramatsu R., Kasuga M. (2009) Identification and characterization of an alternative promoter of the human PGC-1α gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 381, 537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Norrbom J., Sällstedt E. K., Fischer H., Sundberg C. J., Rundqvist H., Gustafsson T. (2011) Alternative splice variant PGC-1α-b is strongly induced by exercise in human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 301, E1092–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cousin B., Cinti S., Morroni M., Raimbault S., Ricquier D., Pénicaud L., Casteilla L. (1992) Occurrence of brown adipocytes in rat white adipose tissue: Molecular and morphological characterization. J. Cell Sci. 103, 931–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guerra C., Koza R. A., Yamashita H., Walsh K., Kozak L. P. (1998) Emergence of brown adipocytes in white fat in mice is under genetic control. Effects on body weight and adiposity. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 412–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Himms-Hagen J., Cui J., Danforth E., Jr., Taatjes D. J., Lang S. S., Waters B. L., Claus T. H. (1994) Effect of CL-316243, a thermogenic β3-agonist, on energy balance and brown and white adipose tissues in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 266, R1371–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Himms-Hagen J., Melnyk A., Zingaretti M. C., Ceresi E., Barbatelli G., Cinti S. (2000) Multilocular fat cells in WAT of CL-316243-treated rats derive directly from white adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C670–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagase I., Yoshida T., Kumamoto K., Umekawa T., Sakane N., Nikami H., Kawada T., Saito M. (1996) Expression of uncoupling protein in skeletal muscle and white fat of obese mice treated with thermogenic β3-adrenergic agonist. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 2898–2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tadaishi M., Miura S., Kai Y., Kawasaki E., Koshinaka K., Kawanaka K., Nagata J., Oishi Y., Ezaki O. (2011) Effect of exercise intensity and AICAR on isoform-specific expressions of murine skeletal muscle PGC-1α mRNA: A role of β2-adrenergic receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 300, E341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dankert J. R., Olson B., Si J. (2008) Asynchronous decision making in a memorized paddle pressing task. J. Neural. Eng. 5, 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boss O., Bachman E., Vidal-Puig A., Zhang C. Y., Peroni O., Lowell B. B. (1999) Role of the β3-adrenergic receptor and/or a putative β4-adrenergic receptor on the expression of uncoupling proteins and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261, 870–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gómez-Ambrosi J., Frühbeck G., Martínez J. A. (2001) Rapid in vivo PGC-1 mRNA up-regulation in brown adipose tissue of Wistar rats by a β3-adrenergic agonist and lack of effect of leptin. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 176, 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cao W., Daniel K. W., Robidoux J., Puigserver P., Medvedev A. V., Bai X., Floering L. M., Spiegelman B. M., Collins S. (2004) p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 3057–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karamanlidis G., Karamitri A., Docherty K., Hazlerigg D. G., Lomax M. A. (2007) C/EBPβ reprograms white 3T3-L1 preadipocytes to a Brown adipocyte pattern of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24660–24669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheng X., Kanki T., Fukuoh A., Ohgaki K., Takeya R., Aoki Y., Hamasaki N., Kang D. (2005) PDIP38 associates with proteins constituting the mitochondrial DNA nucleoid. J. Biochem. 138, 673–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]