Background: Insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) can be down-regulated by antibodies and ligand, but its ubiquitination sites remain unknown.

Results: The IGF-IR ubiquitination sites were mapped to its activation loop adjacent to the phosphorylation sites.

Conclusion: IGF-IR requires phosphorylation of its activation loop followed by Lys-48- and Lys-29-linked ubiquitination for down-regulation.

Significance: This is the first mapping of IGF-IR ubiquitination sites.

Keywords: Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF), Protein Degradation, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, Signal Transduction, Ubiquitination, Down-regulation

Abstract

Ubiquitination has been implicated in negatively regulating insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) activity. Because of the relative stability of IGF-IR in the presence of ligand stimulation, IGF-IR ubiquitination sites have yet to be mapped and characterized, thus preventing a direct demonstration of how the receptor ubiquitination contributes to downstream molecular cascades. We took advantage of an anti-IGF-IR antibody (h10H5) that induces more efficient receptor down-regulation to show that IGF-IR is promptly and robustly ubiquitinated. The ubiquitination sites were mapped to the two lysine residues in the IGF-IR activation loop (Lys-1138 and Lys-1141) and consisted of polyubiquitin chains formed through both Lys-48 and Lys-29 linkages. Mutation of these ubiquitinated lysine residues resulted in decreased h10H5-induced IGF-IR internalization and down-regulation as well as a reduced cellular response to h10H5 treatment. We have therefore demonstrated that IGF-IR ubiquitination contributes critically to the down-regulating and antiproliferative activity of h10H5. This finding is physiologically relevant because insulin-like growth factor I appears to mediate ubiquitination of the same major sites as h10H5 (albeit to a lesser extent), and ubiquitination is facilitated by pre-existing phosphorylation of the receptor in both cases. Furthermore, identification of a breast cancer cell line with a defect in IGF-IR ubiquitination suggests that this could be an important tumor resistance mechanism to evade down-regulation-mediated negative regulation of IGF-IR activity in cancer.

Introduction

Ubiquitination plays an important role in regulating the localization, stability, and activity of receptor tyrosine kinases (1–3). The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to a substrate can be in the form of monoubiquitination of single or multiple lysine residues (multiubiquitination) or polyubiquitination connected through its own lysine residues. Although monoubiquitination is implicated in receptor tyrosine kinase internalization and endocytosis (4), polyubiquitination can have distinct functions depending on the lysine linkage. Canonical Lys-48-linked polyubiquitin is commonly assumed to play the role of targeting proteins for degradation by the 26 S proteasome (5, 6), whereas Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin can function in non-degradation pathways as a scaffold to help assemble multisubunit complexes involved in endocytosis, signal transduction, and DNA repair (7–9). Much less is known about the functions of so-called “atypical ubiquitin” linked via other lysine residues, Lys-6, Lys-11, Lys-27, Lys-29, and Lys-33 (7, 10).

Insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR)5 is a receptor tyrosine kinase critical for cellular proliferation, survival, and transformation (11–13). Upon IGF ligand binding, the intracellular kinase is activated through an autophosphorylation-induced conformational change within the activation loop, which functions as a pseudosubstrate, blocking the catalytic site in the unstimulated state (14). However, the role of ubiquitination in IGF-IR signaling is less well characterized, in part due to the relative stability of IGF-IR upon ligand stimulation (15). Recent studies have identified specific systems and conditions under which IGF-IR exhibits IGF-I-dependent ubiquitination and down-regulation (16–19). Similar to other receptor tyrosine kinases (20, 21), IGF-IR phosphorylation appears to be required for its ubiquitination upon ligand stimulation because mutation of either the catalytic lysine residue (K1003R) or phosphate-modifiable tyrosine residues (Tyr-1131, Tyr-1135, and Tyr-1136) in the activation loop compromises ubiquitination (19).

Three E3 ligases Nedd4, Mdm2, and c-Cbl have been implicated in mediating IGF-IR ubiquitination (16, 17, 22). Although exactly how c-Cbl interacts with IGF-IR remains unknown, Nedd4 and Mdm2 have been demonstrated to exhibit their effects through adaptor molecules Grb10 and β-arrestin, respectively (16, 17). Because Nedd4, Mdm2, and c-Cbl are also E3 ligases for multiple other substrates, analyses of their effects on IGF-IR ubiquitination are often complicated by accompanying changes in these other substrates. Previous deletion analysis revealed that the carboxyl-terminal domain of IGF-IR is required for receptor ubiquitination as well as for downstream MAPK pathway activation (19). However, whether this simply removes the ubiquitin modification sites, prevents binding of adaptor molecule(s)/E3 ligase(s), or causes a gross conformational change remains to be determined. Identification of the exact ubiquitination sites on IGF-IR should permit dissection of the role of ubiquitination in IGF-IR signaling, endocytosis, and down-regulation.

In contrast to the minimal to modest effect of IGF-I on IGF-IR stability, several antagonist anti-IGF-IR antibodies induce efficient receptor endocytosis and degradation (15, 23–30), a mechanism likely contributing to their inhibitory activities. We took advantage of one such antibody, h10H5, to investigate its mechanism of IGF-IR internalization and down-regulation. h10H5 inhibits IGF-IR-mediated signaling by a dual mechanism mediated both by blocking IGF-I/IGF-II binding and by inducing receptor down-regulation without any detectable agonist activity (30). Here we identify the lysines ubiquitinated upon h10H5 treatment and demonstrate that prior phosphorylation and ubiquitination are required for efficient IGF-IR internalization, down-regulation, and inhibition of proliferation by this antibody. The discovery of a human cancer cell line with a defect in IGF-IR ubiquitination and down-regulation but normal signaling capacity lends further support to the importance of this negative regulatory mechanism for IGF-IR function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Cell Lines

Mouse anti-human IGF-IR antibodies h10H5 and 10F5 (Genentech) were generated as described previously (30). Commercially available antibodies were purchased as follows: anti-Mdm2 (Calbiochem), anti-Nedd4 and anti-phosphotyrosine 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology), anti-HA tag clone 12CA5 (Berkeley Antibody Co.), anti-Cbl (BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-Cbl-b (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-β-actin (Sigma), and anti-IGF-IRβ and anti-ubiquitin P4D1 (Cell Signaling Technology).

A549, SK-N-AS, HCC1419, and MHH-ES-1 cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured according to their recommendations. IGF-IR-null murine embryonic fibroblasts (R− MEFs; Ref. 31) were kindly provided by Dr. Renato Baserga (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA). Because serum contains IGF-I, all experiments examining the effect of IGF-I (R&D Systems, catalogue number 291-G1) stimulation were performed in serum-free medium following 5-h serum starvation. Unless otherwise indicated, h10H5 treatment was performed in complete (10% FBS) medium.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis

Immunoprecipitated samples were reduced (with 10 mm DTT) in SDS sample buffer, alkylated with 20 mm iodoacetamide, and separated by 4–20% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE. After Coomassie Blue staining and destaining, gel bands were excised and digested overnight at 37 °C with 0.1 μg of trypsin (Promega). The reactions were quenched, concentrated, and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis. Samples were injected via an autosampler onto an Agilent 1100 microflow HPLC system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Peptides were eluted directly into a nanospray ionization source and analyzed using a Linear Trap Quadrupole-Fourier Transform (LTQ-FT) hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA). Data were collected in data-dependent mode with the parent ion analyzed in the Fourier Transformation Mass Spectrometer (FTMS), and the top five most abundant ions were selected for fragmentation and analysis in the Linear Trap Quadrupole (LTQ). Resultant data were analyzed either using the search algorithm Mascot (Matrix Sciences, London, UK) or by de novo interpretation.

siRNA Knockdowns

The following siRNAs were transfected into A549 or SK-N-AS cells for 72 h using Dharmafect-1 according to the manufacturer's protocol: CCACAAAUCUGAUAGUAUUTT and AAUACUAUCAGAUUUGUGGTT for MDM2, GGAGAGACCAUAUACAUUUTT and AAAUGUAUAUGGUCUCUCCTT for NEDD4, GACACUUUCCGGAUUACUATT and UAGUAAUCCGGAAAGUGUCTT for CBL, and GGACAGACGGAAUCUCACATT and UGUGAGAUUCCGUCUGUCCTT for CBL-B. Non-targeting control siRNAs were ordered from Dharmacon.

Expression Constructs and Retroviral Transduction

Mutations in the kinase domain of IGF-IR were generated by replacing the lysine residues with arginines (KR mutants) using the QuikChangeTM Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The mutants were 2KR (K1138R/K1141R), 5KR (2KR + K1155R/K1203R/K1224R), 13KR (5KR + K968R/K989R/K993R/K1025R/K1058R/K1081R/K1100R/K1120R), K1003R, and 3YF (Y1131F/Y1135F/Y1136F). In addition, an HA tag was introduced at the carboxyl terminus of WT and mutant IGF-IRs. R−, A549, or MHH-ES-1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant IGF-IR were generated by retroviral transduction as described (32). Bulk puromycin-resistant cells with comparable IGF-IR levels were used for biochemical and/or functional analysis.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Sigma), and IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated from lysates using anti-IGF-IR antibody 10F5 (which does not compete with h10H5) as before (30) or alternatively with anti-HA for IGF-IRβ-HA where stated. For analyzing IGF-IR ubiquitination, cell lysis was carried out in dissociation buffer (120 mm sodium chloride, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 25 μm MG-132, and 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide). To ensure that IGF-IR-associating proteins were separated from the receptor, cell lysates were dissolved in 1% (v/v) SDS and heated at 90 °C for 5 min followed by 10-fold dilution with dissociation buffer prior to immunoprecipitation as described above. Cell lysates or immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen), and probed with the indicated antibodies.

Immunofluorescence

R− MEFs stably transfected with WT or mutant IGF-IR were incubated in 8-well glass slides (Lab-Tek II) for 7 or 60 min with 5 μg/ml h10H5 and 25 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 488-transferrin (Molecular Probes) in cell medium containing lysosomal protease inhibitors (5 μm pepstatin A and 10 μg/ml leupeptin (Roche Applied Science)), washed five times on ice, and fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde. Following saponin permeabilization, samples were processed for immunofluorescence as described previously (30) using Cy3-anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, catalogue number 709-166-149) to detect internalized h10H5 and rat anti-mouse lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (1D4B, BD Pharmingen) followed by Cy5-anti-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, catalogue number 712-175-153) to label lysosomes. Slides were viewed by deconvolution microscopy using a DeltaVision® RT System (Applied Precision) using a 60× Olympus Uplano Apo objective. Images were captured with a Photometrics CH350 charge-coupled device camera powered by SoftWorx (version 3.4.4) software and assembled in Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Quantitation of h10H5 Uptake

R− MEFs stably transfected with WT or mutant IGF-IR were plated in 6-well plates to reach ∼80% confluence 2 days later. Cells were incubated with 3 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 488-labeled h10H5 (3.3 molecules of dye/antibody; labeled according to Molecular Probes' instructions) on ice in complete (10% FBS-, 2 mm glutamine-, and 10 mm HEPES-containing) carbonate-independent medium (Invitrogen) for 1 h, washed three times, and then chased in growth medium at 37 °C for 0, 20, or 60 min. Cells were then chilled, detached with 5 mm EDTA in PBS, and either fixed immediately in 2% paraformaldehyde (unquenched) or after quenching for 1 h on ice with 25 μg/ml anti-Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes). Fluorescence intensities were measured by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences), and the amount of internalization for each construct was calculated as the fluorescence of the quenched sample as a percentage of the unquenched sample at each time point after correcting for incomplete quenching and any antibody losses during the chase as described previously (33). Each sample was performed in duplicate, and the results are the average and S.D. of three independent experiments. Statistical significance compared with WT normalized to 100% was determined using the Student's t test with 2 degrees of freedom.

Proliferation Assay

MHH-ES-1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant IGF-IR were seeded onto 96-well plates at 8,000 cells/well and incubated overnight with 10% serum-containing medium containing 4 μg/ml h10H5 or isotype control antibody (gp120) for 1, 2, or 3 days, and then cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescence kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

h10H5 Induces IGF-IR Ubiquitination within the Activation Loop

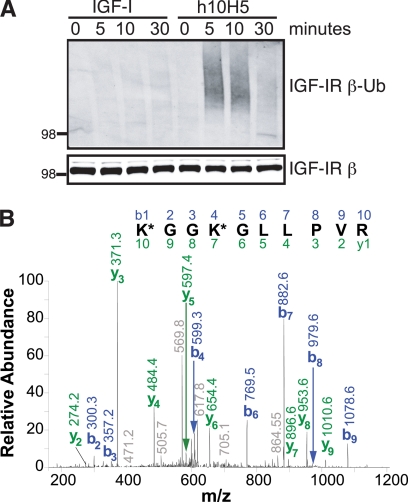

We previously showed that, unlike IGF-I ligand, the anti-IGF-IR antibody h10H5 induces rapid (within 1 h) down-regulation of IGF-IR in SK-N-AS cells via both lysosomal and proteasomal pathways (30). Here we further investigate the molecular mechanisms of this antibody-mediated down-regulation. Because ubiquitination of IGF-IR has recently been implicated in IGF-I and anti-IGF-IR antibody-mediated receptor down-regulation (16, 17, 19, 34), we tested whether a similar mechanism was also utilized after engagement with the antibody h10H5. Serum-starved SK-N-AS cells were thus treated with 100 ng/ml (13 nm) IGF-I or 4 μg/ml (28 nm) h10H5 after which IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated using the non-competing monoclonal antibody 10F5 (30) and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody. IGF-I treatment only slightly increased IGF-IR ubiquitination above basal levels (Fig. 1A); however, h10H5 induced robust, albeit transient, IGF-IR ubiquitination, which peaked at 5–10 min of treatment and waned by 30 min, preceding any significant down-regulation at the receptor level.

FIGURE 1.

h10H5 induces IGF-IR ubiquitination within the activation loop. A, SK-N-AS cells were serum-starved overnight followed by stimulation with either 100 ng/ml IGF-I or 4 μg/ml h10H5 for the indicated times (in minutes). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 10F5 anti-IGF-IR and Western blotted with anti-ubiquitin (Ub) P4D1 (upper panel) and anti-IGF-IRβ subunit (lower panel; ∼100 kDa) antibodies. B, tandem mass spectrum of the [M + 2H]2+ ion (m/z 626.8779) of the doubly ubiquitinated (K*) peptide K*GGK*GLLPVR from IGF-IR. The spectrum was found during data-dependent analysis of the total immunoprecipitate of IGF-IR on the LTQ-FT hybrid mass spectrometer. The m/z matches within −0.06 Da, and the b ion series (in blue; right to left above the sequence) and y ion series (in green; left to right below the sequence) show complete sequence coverage of this peptide.

This strong h10H5-mediated ubiquitination prompted us to search for modification sites on IGF-IR. IGF-IR was therefore immunoprecipitated from SK-N-AS cells that had been treated with h10H5 for 5 min to maximize receptor ubiquitination and analyzed by high resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Ubiquitinated tryptic peptides are characterized by the addition of two glycine residues (molecular mass of 114 Da) for each lysine modification site (35). HPLC-MS/MS analysis revealed a doubly ubiquitinated IGF-IR tryptic peptide (Fig. 1B), which was manually validated and found to match with the precursor mass within 0.7-parts per million (ppm) mass accuracy. This peptide was only identified in the h10H5-treated sample and was absent in the control antibody-treated cells. The identified tryptic peptide contained two lysine residues, Lys-1138 and Lys-1141, which are located in the activation loop of the IGF-IR kinase domain; both residues interestingly are juxtaposed to the phosphorylatable tyrosine residues Tyr-1131, Tyr-1135, and Tyr-1136. Based on the crystal structures of inactive and active IGF-IR kinase domains (14, 36), Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 become more surface-exposed upon phosphorylation-induced conformational changes in the activation loop (supplemental Fig. 1), likely rendering these sites more accessible to ubiquitination. Because various ubiquitin linkages are associated with distinct functions, we performed similar HPLC-MS/MS analyses to determine the nature of the IGF-IR ubiquitination. This revealed polyubiquitination via both canonical Lys-48 and non-canonical Lys-29 polyubiquitin chain linkages in qualitatively similar amounts (supplemental Fig. 2), thus potentially marking IGF-IR for degradation by different pathways. Lys-29 is not a commonly observed polyubiquitin chain linkage and in a global cell lysate analysis typically contributes toward a minimal amount of the total linkages (37), and so this was an unexpected finding.

IGF-IR Ubiquitination Is Required for Efficient Receptor Down-regulation

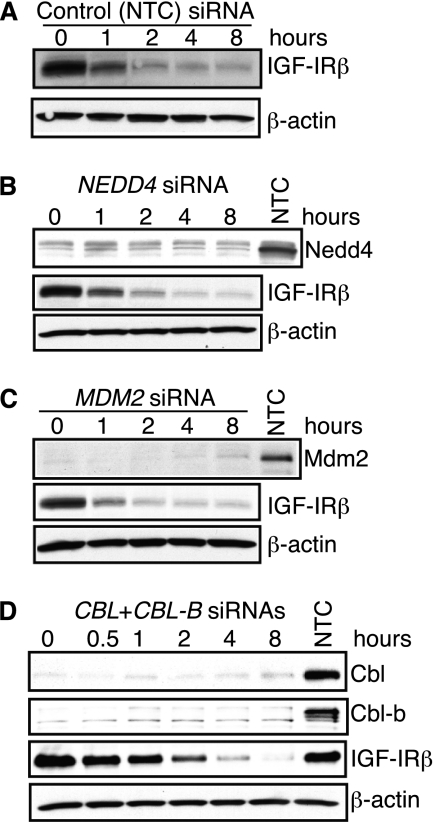

To confirm whether ubiquitination is the key triggering event for h10H5-mediated downstream processes, we took a loss-of-function approach to disrupt this regulation. Three E3 ligases, Nedd4, Mdm2, and c-Cbl, have been reported to participate in ligand-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination (16, 17, 22). Because A549 human lung cancer cells have been shown to undergo IGF-IR ubiquitination upon IGF-I treatment and are more readily transfected than SK-N-AS cells (18), we transfected them with siRNAs to the above E3 ligases. siRNAs against NEDD4, MDM2, or c-CBL/CBL-B, but not the non-targeting control siRNA, caused significant depletion of their respective proteins but did not alter the kinetics of h10H5-mediated IGF-IR down-regulation (Fig. 2), suggesting redundancy among these and/or use of other E3 ligases.

FIGURE 2.

siRNA-mediated MDM2, NEDD4, or CBL and CBL-B depletion does not affect h10H5-induced IGF-IR degradation. Non-targeting control (NTC) siRNA (A) or siRNAs against NEDD4 (B), MDM2 (C), or a mixture of CBL and CBL-B (D) were transfected into A549 cells. After 72 h, the cells were treated with 2 μg/ml h10H5 and harvested at the indicated time points. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting (without prior immunoprecipitation) with anti-IGF-IRβ antibodies to examine down-regulation of endogenous IGF-IR (A–D) and anti-Nedd4 (∼100 kDa) (B), anti-Mdm2 (∼90 kDa) (C), and anti-Cbl and anti-Cbl-b (∼120 kDa) (D) antibodies to verify gene knockdown. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

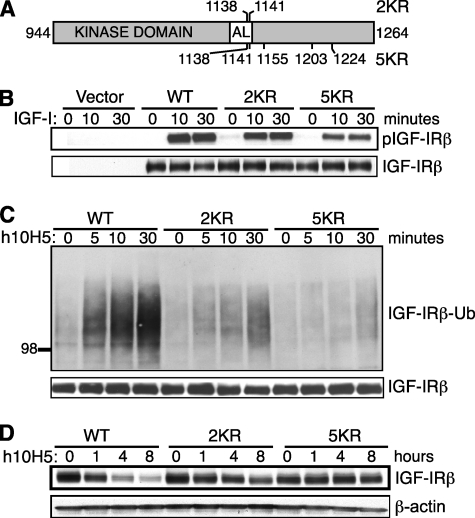

Identification of the ubiquitination sites allowed us to take an alternative approach to investigate the role of IGF-IR ubiquitination by mutating them to prevent ubiquitination. We thus generated lysine to arginine mutations in IGF-IR: 2KR has both the identified lysines mutated (K1138R/K1141R), and 5KR (2KR + K1155R/K1203R/K1224R) has the three additional neighboring lysine residues mutated to prevent any utilization of cryptic ubiquitination sites when the major sites are mutated (Fig. 3A). WT, 2KR, and 5KR IGF-IR expression vectors were retrovirally transduced into R− MEFs (31), which were chosen to avoid any potential interference from endogenous IGF-IR signaling. Similar levels of IGF-IR proteins were produced from the puromycin-resistant cell pools for all three versions of IGF-IR (Fig. 3B, bottom panel), so we compared their signaling capacity and their response to h10H5 treatment. Serum-starved R− MEF lines were stimulated with IGF-I, and then IGF-IRs were immunoprecipitated and examined for tyrosine phosphorylation by Western blotting. 2KR IGF-IR exhibited comparable (or only slightly decreased) phosphorylation relative to the WT receptor, whereas 5KR showed more decreased levels (Fig. 3B). Phosphorylation of AKT and MAPK, two major downstream pathways, was similar among WT, 2KR, and 5KR IGF-IRs (data not shown), although IGF-IR phosphorylation may not be a rate-limiting step for these signaling events. Therefore, the conservative changes in 2KR and 5KR have a mild effect on IGF-IR kinase activity, which was somewhat unexpected. We next extended our analysis to the antibody-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination by treating the (non-starved) cells with h10H5 and probing the IGF-IR immunoprecipitates with anti-ubiquitin. Although WT IGF-IR exhibited the expected rapid increase ubiquitination within 5–30 min of h10H5 treatment, there was significantly less ubiquitination of 2KR and even less ubiquitination of 5KR over the same time course (Fig. 3C), supporting the identification of Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 in the activation loop as the primary modification sites. However, residual ubiquitination was still present in both mutants, indicating additional minor modification sites and/or that other lysine residues can partially substitute for mutated Lys-1138/1141. In accordance with the reduced ubiquitination in 2KR and 5KR mutants, their kinetics of h10H5-induced receptor down-regulation were also delayed (Fig. 3D). WT IGF-IR was depleted by 80% within 4 h of treatment, whereas 2KR IGF-IR was more stable with only ∼50% degraded in 4 h and ∼70% degraded in 8 h. 5KR IGF-IR was more stable still with essentially no detectable degradation during the 8-h time course. Taken together, these data suggest that IGF-IR ubiquitination induced by h10H5 is required for efficient receptor down-regulation.

FIGURE 3.

2KR and 5KR IGF-IRs exhibit decreased h10H5-induced ubiquitination and receptor down-regulation. A, schematic of the IGF-IR kinase domain (amino acids 944–1264 of human IGF-IR in gray with the activation loop (AL; amino acids 1122–1143) in white) drawn to scale, showing the positions of the lysine to arginine substitutions in mutants 2KR (above) and 5KR (below). B, 2KR and 5KR IGF-IRs are competent for signaling. R− MEFs stably expressing WT, 2KR, or 5KR IGF-IR or empty vector were serum-starved for 5 h and stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I for the indicated time points. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-IGF-IR antibody 10F5 and Western blotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (upper panel) or IGF-IRβ subunit (lower panel; loading control). C, 2KR and 5KR IGF-IRs exhibit decreased h10H5-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination. R− MEFs stably expressing WT or mutant IGF-IR were treated with 4 μg/ml h10H5 (in 10% FBS medium) for the indicated time points. IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated with 10F5 and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody P4D1 and IGF-IRβ subunit (loading control). D, 2KR and 5KR IGF-IRs are more resistant to h10H5-induced IGF-IR down-regulation. Cells were treated as in C except for longer time points, and the kinetics of IGF-IR down-regulation were analyzed by direct Western blotting with anti-IGF-IRβ versus β-actin loading control.

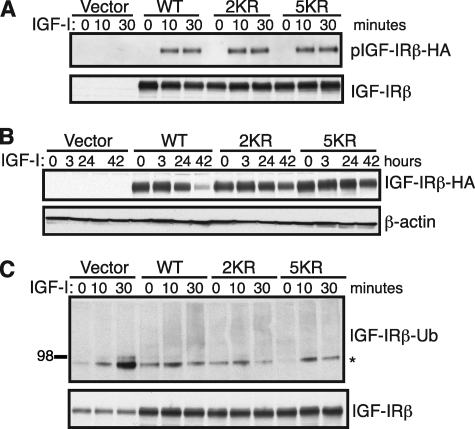

Because anti-IGF-IR antibodies represent a therapeutic intervention rather than normal receptor physiology, we next examined whether the same ubiquitination sites are also utilized during normal ligand-dependent stimulation by IGF-I. To this end, we transduced A549 cells with HA-tagged WT, 2KR, or 5KR IGF-IR to enable immunoprecipitation of exogenous IGF-IR with anti-HA tag antibodies. HA-tagged WT and mutant IGF-IRs exhibited comparable expression (Fig. 4A, lower panel, 0 min lanes) and similar levels of IGF-I-induced receptor tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 4A, upper panel). The lack of changes in phosphorylation compared with the mild decreases in R− cells (Fig. 3B) may be attributable to the existence of endogenous IGF-IR in A549 cells that can heterodimerize with the transfected proteins and obscure any small changes in phosphorylation. Nonetheless, compared with h10H5, IGF-I stimulation resulted in much slower kinetics of receptor down-regulation (Fig. 4B) as seen previously for endogenous IGF-IR in MCF7 cells (30). WT IGF-IR did not show any detectable down-regulation until 42 h, by which time it was depleted by 81% compared with only 36 and 25% for 2KR and 5KR, respectively, suggesting that these mutations also reduce ligand-dependent IGF-IR turnover. We also examined their ubiquitination and found that it was defective in both mutants, although the differences compared with WT were smaller because IGF-I-mediated ubiquitination levels were so low even in WT that they were only just detectable at the 30-min time point (Fig. 1C). Thus, our data suggest that Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 are utilized as the key modification sites in IGF-I-induced as well as h10H5-induced receptor ubiquitination.

FIGURE 4.

2KR and 5KR mutations affect IGF-I-induced IGF-IR down-regulation and ubiquitination. A, HA-tagged WT, 2KR, and 5KR IGF-IRs are comparable in their signaling capacity. A549 cells stably expressing WT or 2KR or 5KR mutant IGF-IRβ-HA were serum-starved for 5 h and stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I for 10 or 30 min. Transfected IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10. B, 2KR and 5KR IGF-IRs are more resistant to IGF-I-mediated IGF-IR down-regulation. A549 cells stably expressing HA-tagged WT or mutant IGF-IR were treated with 4 μg/ml h10H5 for 3, 24, or 42 h. The kinetics of receptor down-regulation were analyzed by direct Western blotting with an anti-HA antibody. C, 2KR and 5KR IGF-IRs exhibit decreased IGF-I-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination. Cells were treated as in A except immunoprecipitates were Western blotted with the anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody P4D1. Total IGF-IR (A and C) and β-actin (B) were used as loading controls. Note that the ubiquitination induced by IGF-I is much less extensive than that induced by h10H5 in Fig. 3. The asterisk denotes a nonspecific ubiquitin band immunoprecipitated by the anti-HA antibody (present also in the empty vector control cells).

Phosphorylation Facilitates h10H5-induced Ubiquitination

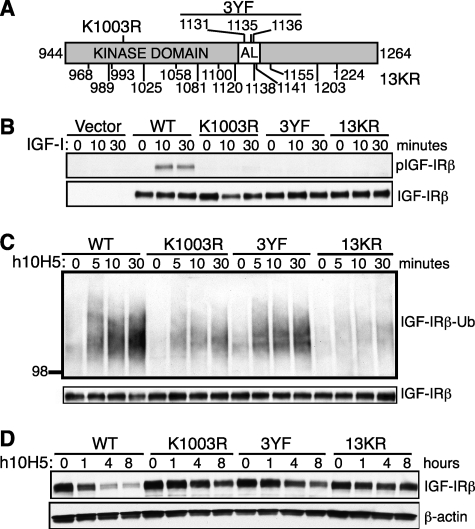

Phosphorylation of IGF-IR appears to be required for IGF-I-mediated receptor ubiquitination (19). To determine whether a similar relationship also exists for h10H5, we generated R− cells expressing two mutants defective in IGF-IR phosphorylation: an inactive kinase with its catalytic lysine replaced with arginine (K1003R) and a mutant IGF-IR with its activation loop locked in the inactive conformation (3YF; Y1131F/Y1135F/Y1136F; Fig. 5A). In addition, we substituted all 13 lysine residues in the kinase domain except Lys-1003 with arginine to control for background levels of ubiquitination (13KR). All mutants were expressed at similar levels (Fig. 5B, bottom panel), and as expected, neither K1003R nor 3YF exhibited any IGF-I-dependent receptor phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, top panel). Surprisingly, the 13KR ubiquitination mutant was as defective in phosphorylation as K1003R and 3YF despite retaining the catalytic lysine at Lys-1003. It is unclear whether this is due to a conformational change induced by so many mutations or whether ubiquitination affects the stability of the phosphorylation groups. The kinetics of h10H5-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination revealed a moderate decrease in ubiquitination in 3YF and a strong decrease in K1003R, although to a lesser extent than the positive control ubiquitination mutant 13KR. Thus, IGF-IR phosphorylation is important for efficient receptor ubiquitination, although it is not absolutely required. The time courses of degradation were also compared: correlating with the extent of the receptor ubiquitination, WT IGF-IR was depleted 28, 72, and 76% after 1, 4, and 8 h of continuous h10H5 treatment, respectively, whereas K1003R and 3YF were only decreased 29 and 51% at 8 h, respectively. 13KR exhibited minimal changes in receptor levels over the entire time course in agreement with its lack of ubiquitination. Taken together, these data demonstrate that IGF-IR phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and down-regulation are a series of interdependent events with the robustness of the latter events depending on the former events.

FIGURE 5.

IGF-IR phosphorylation is required for efficient receptor ubiquitination. A, to-scale schematic of the IGF-IR kinase domain (gray with the activation loop (AL) in white) showing the positions of the K1003R, 3YF (three tyrosines to phenylalanines), and 13KR (all 13 lysines in the kinase domain to arginines (except K1003)) mutants. B, K1003R, 3YF, and 13KR IGF-IRs are defective in IGF-I-mediated signaling. R− MEFs with WT or mutant IGF-IR or empty vector were serum-starved for 5 h and stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I for 10 or 30 min. IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated with 10F5 and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10. C, K1003R, 3YF, and 13KR IGF-IRs exhibit decreased h10H5-mediated receptor ubiquitination. R− MEFs stably expressing WT or mutant IGF-IR were treated with 4 μg/ml h10H5 in complete (10% FBS, which contains IGF-I) medium for 5, 10, or 30 min, and then IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated with 10F5 and Western blotted with anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody P4D1. D, as in C except h10H5 treatment was for 1, 4, or 8 h, and the lysates were Western blotted with anti-IGF-IRβ subunit antibody without prior immunoprecipitation to analyze the kinetics of receptor down-regulation. Total IGF-IR (B and C) and β-actin (D) were used loading controls.

IGF-IR Ubiquitination Facilitates Efficient Receptor Endocytosis

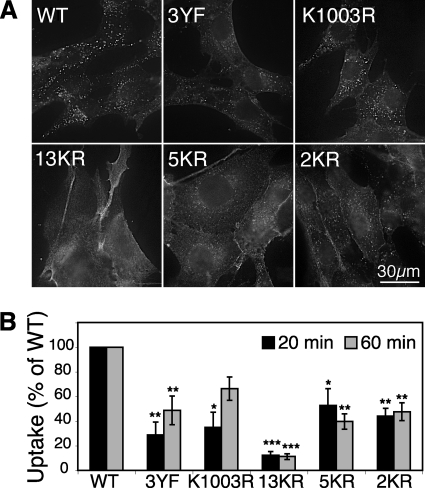

Our studies have clearly demonstrated a link between h10H5-induced IGF-IR ubiquitination and down-regulation. However, there are several intermediate steps, such as receptor internalization and trafficking, before IGF-IR becomes accessible to the proteasomal and lysosomal degradation machineries (30, 34). We therefore examined internalization of h10H5 by all five ubiquitination-defective IGF-IR mutants in R− cells by immunofluorescence. Consistent with previous studies in MCF7 cells (30), WT IGF-IR was rapidly internalized by h10H5 as demonstrated by numerous h10H5-positive cytoplasmic puncta after 7 min; most of the WT IGF-IR vesicles co-localized with the clathrin-mediated endocytic cargo transferrin (supplemental Fig. 3). 2KR and 5KR mutants produced far fewer h10H5-positive vesicles, although their similar co-localization with transferrin implies they also are internalized via a clathrin-dependent route, whereas no vesicles were detected at all for the other three mutants (13KR, K1003R, and 3YF) at this early time point, suggesting that autophosphorylation may be more important than ubiquitination for initiation of IGF-IR endocytosis. After 60 min of uptake, the majority of the h10H5 signal was internalized in WT IGF-IR cells (Fig. 6A), mostly co-localizing with the late endosomal and lysosomal marker lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (supplemental Fig. 4). By contrast, plasma membrane signal was still readily visible in all the mutants, indicating less uptake, particularly for 13KR, which remained almost exclusively at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6A), comparable with cells retained on ice (data not shown). 2KR, 5KR, K1003R, and 3YF mutants all exhibited decreases in the numbers of cytoplasmic vesicles and extent of lysosomal co-localization compared with WT (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. 4).

FIGURE 6.

Immunofluorescence and quantitative flow cytometry analysis of h10H5 uptake. A, R− MEFs transfected with WT or all the mutant IGF-IRs (or vector alone, which gave no specific signal; not shown) were incubated for 60 min with h10H5 in the presence of lysosomal protease inhibitors to inhibit lysosomal degradation, fixed, and permeabilized, and the total antibody was detected with Cy3-anti-human IgG. Scale bar, 30 μm. See supplemental Fig. 4 for overlays with lysosomes. B, R− MEFs transfected with WT or mutant IGF-IR were incubated on ice for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled h10H5, washed, and chased for 20 or 60 min in the presence of lysosomal protease inhibitors, and then any remaining surface antibody was quenched with anti-Alexa Fluor 488 antibodies. Following flow cytometry measurements, the percentage of internalized h10H5 at each time point (after correcting for any losses or incomplete quenching) was calculated from three independent duplicate experiments, each normalized to WT as 100%, with mean and Standard Deviation of the Mean shown. *, p = 0.05; **, p = 0.01; ***, p = 0.001 versus WT (by Student's t test).

These results were confirmed quantitatively by flow cytometry using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated h10H5 prebound to cells on ice. After chasing at 37 °C for 20 or 60 min, any remaining surface Alexa Fluor 488-h10H5 was quenched with anti-Alexa Fluor 488 antibodies to determine the percentage of internalized h10H5. After 20 min, internalization was significantly defective compared with WT in all the mutants: 13KR, internalization decreased to 12% of WT levels; 2KR, 44%; 5KR, 53%; 3YF, 29%; and K1003R, 35%. Prolonged incubation for 60 min did not further enhance the internalization of the 13KR, 2KR, or 5KR mutants, whereas a modest increase was observed for the phosphorylation-defective mutants, albeit still less than WT: 66% of WT levels for K1003R and 49% for 3YF. Taken together, these data confirm that h10H5-induced IGF-IR ubiquitination is important for efficient receptor internalization and subsequent delivery to lysosomes, with the two identified lysines (2KR) playing a major, but not the only, role.

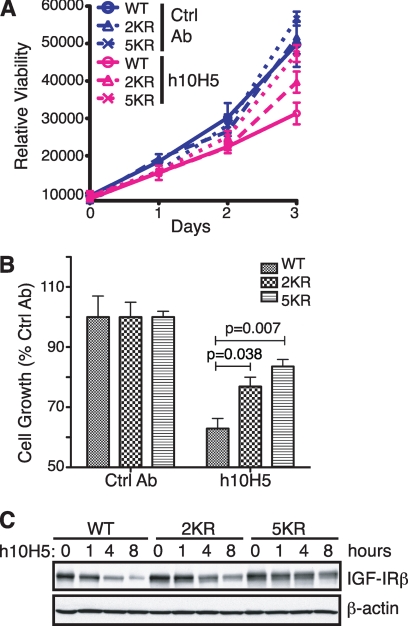

Ubiquitination-dependent IGF-IR Down-regulation Contributes to Inhibitory Activity of h10H5

Two independent mechanisms of action have been described for several anti-IGF-IR antibodies: first, blocking IGF ligand binding to IGF-IR, thereby inhibiting ligand-dependent downstream signaling, and second, actively inducing IGF-IR down-regulation (15, 23, 26–28, 30). However, it remains to be determined how these two mechanisms contribute to the full activity of the antibodies. The ubiquitination mutants provided us with an opportunity to analyze these two distinct roles separately for h10H5. We first identified a cell line that was responsive to h10H5 inhibition (presumably possessing the downstream signaling machinery) but expressed IGF-IR at levels low enough not to interfere with transfected IGF-IR constructs: MHH-ES1 cells, a human Ewing sarcoma cell line. WT, 2KR, and 5KR IGF-IR expression vectors were transduced into MHH-ES1 cells, and growth was measured using an in vitro proliferation assay. MHH-ES1 cells expressing WT and mutant IGF-IRs were comparable in their growth rates in the presence of a control antibody (Fig. 7, A and B). However, h10H5 treatment resulted in 37% growth inhibition in the cells expressing WT IGF-IR at 72 h, but only 23 and 16% inhibition in the 2KR- and 5KR-expressing cells, respectively (Fig. 7, A and B); both mutants were statistically significantly different from WT. As expected, mutant IGF-IRs, especially 5KR, in the MHH-ES1 cells were relatively stable despite h10H5 treatment (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the low extent of growth inhibition in these mutants is primarily due to the ligand-blocking activity of h10H5. The extra inhibition (37 − 16% = 21%; i.e. ∼half) observed in the cells carrying WT IGF-IR likely results from combined down-regulation of the receptor in addition to ligand blocking; thus, h10H5 likely utilizes both mechanisms to inhibit tumor growth (30).

FIGURE 7.

Cells expressing 2KR or 5KR IGF-IR are more resistant to h10H5-mediated growth inhibition. A, time course of the effect of h10H5 treatment on the viability of MHH-ES-1 cells stably expressing HA-tagged WT or 2KR or 5KR mutant IGF-IR. Cells were treated with 10 μg/ml h10H5 or isotype control anti-gp120 antibody (Ctrl Ab), and cell growth was monitored by the CellTiter-Glo luminescence viability assay at 1, 2, and 3 days with means and Standard Deviation of the Mean of triplicates shown. B, 3-day CellTiter-Glo time point from A normalized to 100% for the gp120 control antibody. Statistical analysis using the Student's t test was performed by comparing mutant versus WT IGF-IR groups treated with h10H5. C, MHH-ES-1 cells expressing WT, 2KR, or 5KR IGF-IR-HA were treated with 2 μg/ml h10H5 for the indicated time points. The kinetics of receptor down-regulation were analyzed by direct Western blotting with anti-HA versus β-actin loading control.

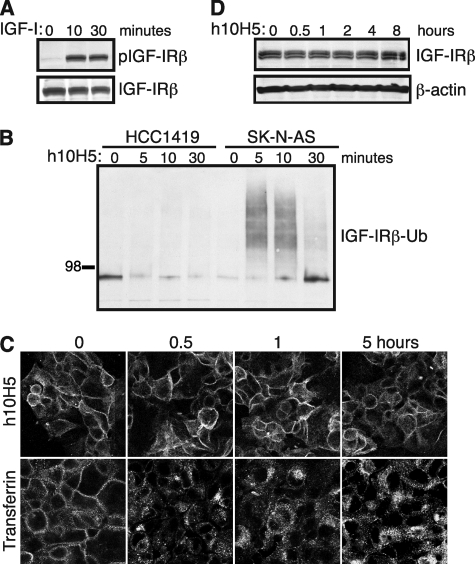

Deficiency of h10H5-induced Ubiquitination in Cancer Cells

Our data suggest that IGF-IR ubiquitination negatively regulates receptor-mediated signaling by promoting receptor down-regulation. We therefore examined IGF-IR ubiquitination in a panel of cancer cell lines to determine whether any of the cell types had developed mechanisms of evading such regulation. One cell line, human breast cancer HCC1419 cells, exhibited increased receptor phosphorylation upon IGF-I treatment (Fig. 8A), showing that they are ligand-responsive, in line with their lack of IGF-IR mutations as determined by sequencing (data not shown). However, unlike SK-N-AS cells, they failed to show any IGF-IR polyubiquitination upon h10H5 treatment (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, HCC1419 cells were specifically defective in IGF-IR internalization but were competent at internalizing transferrin (Fig. 8C) and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF; data not shown). Correlating with these ubiquitination and internalization defects, IGF-IR was stable throughout the entire 8-h time course of h10H5 treatment (Fig. 8D). Thus, HCC1419 cells do not down-regulate IGF-IR upon antibody treatment due to a defect in receptor ubiquitination.

FIGURE 8.

HCC1419 breast cancer cells exhibit defective h10H5-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination, internalization, and down-regulation. A, HCC1419 cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 100 ng/ml IGF-I for 0, 10, or 30 min. Endogenous IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated with 10F5 and analyzed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10. Total IGF-IRβ subunit was used a loading control. B, HCC1419 and SK-N-AS cells were treated with h10H5 for the time points indicated, and IGF-IR was immunoprecipitated with 10F5 and analyzed with anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody P4D1. C, HCC1419 cells were incubated on ice for 30 min with Alexa Fluor 555-h10H5 (top) or Alexa Fluor 555-transferrin (bottom); washed; chased at 37 °C for 0.5, 1, or 5 h; then fixed, and imaged. D, HCC1419 cells were treated with h10H5 for the indicated time points, and IGF-IRβ subunit levels were analyzed by direct Western blotting compared with β-actin loading control.

DISCUSSION

We mapped h10H5-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination sites to Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 in the activation loop of the kinase domain adjacent to phosphorylation sites Tyr-1134 and Tyr-1135 and provided clear evidence through mutagenesis that IGF-IR ubiquitination is a key triggering event leading to efficient receptor internalization and degradation in multiple cell lines, thereby contributing to the antiproliferative activity of this antibody. Substitution of the two major ubiquitinated lysines with arginines (2KR) decreased h10H5-induced ubiquitination, endocytosis, and down-regulation, suggesting that IGF-IR ubiquitination at these sites is important for endocytic down-regulation. The same mutations also decreased IGF-I-dependent receptor down-regulation, suggesting that Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 are also crucial for ligand-induced IGF-IR ubiquitination. The similarity between IGF-I- and h10H5-induced IGF-IR ubiquitination extends beyond the conserved ubiquitination sites, with both processes having similar wax and wane kinetics and possibly depending on IGF-IR phosphorylation because IGF-IR phosphorylation mutants also failed to exhibit significant IGF-I- or antibody-induced ubiquitination. These data help delineate an interdependent molecular cascade, which starts with IGF-I/II-induced IGF-IR autophosphorylation followed sequentially by h10H5-induced receptor ubiquitination, endocytosis, and down-regulation with IGF-IR ubiquitination as a critical trigger for the latter events. Although IGF-IR phosphorylation appears to facilitate ubiquitination, it is not absolutely required because the 3YF mutant (which blocks phosphorylation of the activation loop) and the K1003R mutant (which is catalytically inactive) did exhibit low levels of ubiquitination. It is unclear, however, whether ubiquitination reciprocally regulates IGF-IR phosphorylation given that in R− cells the 5KR and 13KR (and to a lesser extent the 2KR) ubiquitination mutants also showed defects in phosphorylation. In WT IGF-IR, the Lys-1138 residue forms a salt bridge to phosphorylated Tyr-1136, stabilizing the active conformation of the kinase domain (14). Ubiquitination of Lys-1138 would disrupt this salt bridge with correspondingly reduced kinase activity and hence autophosphorylation. Mutation of Lys-1138 to Arg would not necessarily prevent salt bridge formation but could change its conformation somewhat. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other kinases may mediate IGF-IR phosphorylation at other sites, although current models posit that IGF-IR is only transphosphorylated by itself (14, 44).

The identification of ubiquitination sites Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 in the intracellular activation loop helps explain our previous finding that the stability of the intracellular domain of IGF-IR is increased by proteasomal inhibition (30). Although we did not map IGF-dependent IGF-IR ubiquitination sites, the 2KR and 5KR mutations that inhibited h10H5 ubiquitination and down-regulation also delayed the kinetics of ligand-induced down-regulation, suggesting that the primary Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 modification sites are shared by h10H5 and IGF-I. This is perhaps not surprising given that both the antibody and ligand require receptor phosphorylation for efficient ubiquitination: IGF-I induces phosphorylation, whereas h10H5 ubiquitination is facilitated by prior phosphorylation of the receptor (likely via IGF-I/II in the FBS because this antibody blocks IGF binding). Such priming of ubiquitination by prior phosphorylation has been well documented for cytosolic proteins such as Skp1-Cullin1-F-box (SCF) E3 ligase substrates (for a review, see Ref. 38) but is poorly documented for cell surface receptors. In the case of IGF-IR, priming may be explained by structural modeling, which suggests that phosphorylation-induced structural changes in the activation loop could render Lys-1138 and Lys-1141 more accessible to ubiquitination. Alternatively, because the phosphorylation mutants (3YF and K1003R) also showed delayed internalization (especially at early time points), it is possible that phosphorylation facilitates endocytic trafficking of IGF-IR to a site harboring the E3 ligases that mediate ubiquitination. Despite sharing the same ubiquitination sites, the efficiency of ubiquitination is far lower for IGF-I than h10H5, likely explaining the much less efficient ligand-mediated down-regulation.

Other than the extent of ubiquitination and down-regulation, there are also notable differences between ligand- and antibody-induced IGF-IR ubiquitination with respect to the E3 ligases utilized. Three E3 ligases, Nedd4, Mdm2, and Cbl, have been implicated in ligand-mediated ubiquitination (16, 17, 22). Nedd4-dependent ubiquitination was shown by the use of antibodies preferentially recognizing polyubiquitin chains over single ubiquitin molecules to induce multiubiquitination of IGF-IR (39). In contrast, Mdm2 and c-Cbl conjugate polyubiquitin chains onto IGF-IR with distinct Lys-63 and Lys-48 linkages in an in vitro reconstitution system, respectively (22). The engagement of Mdm2 and c-Cbl correlates with low (5 ng/ml) and high (50–100 ng/ml) IGF-I levels, respectively. Therefore, ligand-mediated IGF-IR ubiquitination is subject to a complex regulation that is influenced by cellular context and growth conditions.

By contrast, anti-IGF-IR antibodies, including h10H5, can induce IGF-IR down-regulation more robustly and consistently than ligand in a variety of cells, utilizing both lysosomal and proteasomal degradation pathways (30). Depletion of NEDD4, MDM2, or c-CBL/CBL-B individually by siRNA treatment did not affect the kinetics of h10H5-induced down-regulation, suggesting simultaneous engagement of at least two of the known E3 ligases or the involvement of uncharacterized E3 ligase(s) in this process. Nedd4 and Mdm2 may be the most likely candidates because they have been associated with clathrin-dependent endocytosis, the route by which h10H5 was likely internalized in our cell lines (supplemental Fig. 3 and Ref. 30), whereas c-Cbl has been associated with caveolin-dependent endocytosis of IGF-IR (22). h10H5 treatment resulted not only in Lys-48-linked polyubiquitination, marking the receptor for proteasomal degradation similar to c-Cbl, but also in Lys-29-linked polyubiquitination. This adds IGF-IR to a short list of proteins known to use Lys-29 linkages, including NFκB essential modulator (NEMO) and p65 (ubiquitinated by TRAF7) in the NFκB pathway (9, 40) and Deltex (ubiquitinated by AIP4/Itch) in the Notch pathway (41), all of which are thus targeted for lysosomal degradation as we now observed for IGF-IR. However, not all known cases of Lys-29-mediated polyubiquitination result in lysosomal degradation because on the AMP-activated protein kinase-related kinases NUAK1 and MARK4 ubiquitination via Lys-29 (and Lys-33) linkages appears to inhibit their phosphorylation and activation by the kinase LKB1 instead (42); thus, the known functions of Lys-29-linked ubiquitin are not yet fully understood. As discussed above, we cannot exclude a role for ubiquitination in regulating IGF-IR phosphorylation, although our data clearly show that lysosomal trafficking and IGF-IR degradation were impaired if ubiquitination was defective.

Ubiquitination of receptor tyrosine kinases is frequently associated with their internalization. However, mutation of the major ubiquitination sites in EGF receptor only resulted in increased receptor stability while failing to decrease EGF receptor internalization (43). In our study, 2KR and 5KR IGF-IR mutants exhibited decreased internalization as well as increased stability, suggesting that IGF-IR internalization is a prerequisite for intracellular lysosomal and proteasomal degradation. The difference between the two systems could be due to their different ubiquitin modifications. Over 50% of EGF receptors have Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin in response to EGF stimulation, whereas IGF-IR exhibits exclusively Lys-48- and Lys-29-linked polyubiquitin upon h10H5 treatment (although it is unclear whether IGF-I ligand does the same). Thus, the nature and extent of polyubiquitination seem to dictate the functional outcome (although again the triggers are different).

In conclusion, we delineated the order of a series of h10H5-triggered molecular events, starting with pre-existing IGF-IR phosphorylation followed by sequential receptor ubiquitination, internalization, and down-regulation. Furthermore, we identified a cell line (HCC1419) that is resistant to ubiquitination and down-regulation despite having no ubiquitination site or other IGF-IR mutations. It therefore appears possible for cancer cells to develop a defect in IGF-IR ubiquitination that prevents the negative regulation of receptor activity, further supporting IGF-IR ubiquitination as an upstream event required for receptor internalization and down-regulation. Although it remains to be determined how this defect in ubiquitination occurs and how common this is among tumor cells, we speculate that resistance to ubiquitination might be an important mechanism to maximize IGF-dependent signaling for tumor growth or to become resistant to anti-IGF-IR antibody therapeutics. Furthermore, monitoring receptor ubiquitination could possibly be a means of identifying anti-IGF-IR non-responders in the clinic. Anti-IGF-IR antibodies have provided successful examples of how to inhibit receptor tyrosine kinase activity by increasing receptor ubiquitination and down-regulation. Promoting the turnover of key signaling molecules required for cancer growth and survival could be applied as a general therapeutic strategy. In addition to enhancing recruitment of E3 ligases, inhibiting deubiquitinating enzymes offers an alternative approach to regulate protein stability. A combination of both strategies may further augment the inhibition of the signaling pathways critical for tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Renato Baserga for generously providing IGF-IR-null MEFs.

All authors conducted this work while employees of Genentech, a member of the Roche group.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- IGF-IR

- insulin-like growth factor I receptor

- IGF

- insulin-like growth factor

- R−

- IGF-IR-null

- MEF

- murine embryonic fibroblast.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dikic I., Giordano S. (2003) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marmor M. D., Yarden Y. (2004) Oncogene 23, 2057–2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miranda M., Sorkin A. (2007) Mol. Interv. 7, 157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haglund K., Sigismund S., Polo S., Szymkiewicz I., Di Fiore P. P., Dikic I. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chau V., Tobias J. W., Bachmair A., Marriott D., Ecker D. J., Gonda D. K., Varshavsky A. (1989) Science 243, 1576–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gregori L., Poosch M. S., Cousins G., Chau V. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 8354–8357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ikeda F., Dikic I. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 536–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Z. J., Sun L. J. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jin Z., Li Y., Pitti R., Lawrence D., Pham V. C., Lill J. R., Ashkenazi A. (2009) Cell 137, 721–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu P., Duong D. M., Seyfried N. T., Cheng D., Xie Y., Robert J., Rush J., Hochstrasser M., Finley D., Peng J. (2009) Cell 137, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baserga R., Peruzzi F., Reiss K. (2003) Int. J. Cancer 107, 873–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LeRoith D., Roberts C. T., Jr. (2003) Cancer Lett. 195, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollak M. N., Schernhammer E. S., Hankinson S. E. (2004) Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 505–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Favelyukis S., Till J. H., Hubbard S. R., Miller W. T. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 1058–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burtrum D., Zhu Z., Lu D., Anderson D. M., Prewett M., Pereira D. S., Bassi R., Abdullah R., Hooper A. T., Koo H., Jimenez X., Johnson D., Apblett R., Kussie P., Bohlen P., Witte L., Hicklin D. J., Ludwig D. L. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 8912–8921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Girnita L., Girnita A., Larsson O. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8247–8252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vecchione A., Marchese A., Henry P., Rotin D., Morrione A. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3363–3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carelli S., Di Giulio A. M., Paratore S., Bosari S., Gorio A. (2006) J. Cell. Physiol. 208, 354–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sehat B., Andersson S., Vasilcanu R., Girnita L., Larsson O. (2007) PLoS One 2, e340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Ettenberg S. A., Katz M., Tsygankov A. Y., Alroy I., Lavi S., Iwai K., Reiss Y., Ciechanover A., Lipkowitz S., Yarden Y. (1999) Mol. Cell 4, 1029–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peschard P., Fournier T. M., Lamorte L., Naujokas M. A., Band H., Langdon W. Y., Park M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 995–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sehat B., Andersson S., Girnita L., Larsson O. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 5669–5677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maloney E. K., McLaughlin J. L., Dagdigian N. E., Garrett L. M., Connors K. M., Zhou X. M., Blättler W. A., Chittenden T., Singh R. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 5073–5083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. García-Echeverría C., Pearson M. A., Marti A., Meyer T., Mestan J., Zimmermann J., Gao J., Brueggen J., Capraro H. G., Cozens R., Evans D. B., Fabbro D., Furet P., Porta D. G., Liebetanz J., Martiny-Baron G., Ruetz S., Hofmann F. (2004) Cancer Cell 5, 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mitsiades C. S., Mitsiades N. S., McMullan C. J., Poulaki V., Shringarpure R., Akiyama M., Hideshima T., Chauhan D., Joseph M., Libermann T. A., García-Echeverría C., Pearson M. A., Hofmann F., Anderson K. C., Kung A. L. (2004) Cancer Cell 5, 221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen B. D., Baker D. A., Soderstrom C., Tkalcevic G., Rossi A. M., Miller P. E., Tengowski M. W., Wang F., Gualberto A., Beebe J. S., Moyer J. D. (2005) Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 2063–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goetsch L., Gonzalez A., Leger O., Beck A., Pauwels P. J., Haeuw J. F., Corvaia N. (2005) Int. J. Cancer 113, 316–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Y., Hailey J., Williams D., Wang Y., Lipari P., Malkowski M., Wang X., Xie L., Li G., Saha D., Ling W. L., Cannon-Carlson S., Greenberg R., Ramos R. A., Shields R., Presta L., Brams P., Bishop W. R., Pachter J. A. (2005) Mol. Cancer Ther. 4, 1214–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yee D. (2006) Br. J. Cancer 94, 465–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shang Y., Mao Y., Batson J., Scales S. J., Phillips G., Lackner M. R., Totpal K., Williams S., Yang J., Tang Z., Modrusan Z., Tan C., Liang W. C., Tsai S. P., Vanderbilt A., Kozuka K., Hoeflich K., Tien J., Ross S., Li C., Lee S. H., Song A., Wu Y., Stephan J. P., Ashkenazi A., Zha J. (2008) Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 2599–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li S., Ferber A., Miura M., Baserga R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 32558–32564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. John G. B., Shang Y., Li L., Renken C., Mannella C. A., Selker J. M., Rangell L., Bennett M. J., Zha J. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1543–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Austin C. D., De Mazière A. M., Pisacane P. I., van Dijk S. M., Eigenbrot C., Sliwkowski M. X., Klumperman J., Scheller R. H. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5268–5282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Broussas M., Dupont J., Gonzalez A., Blaecke A., Fournier M., Corvaïa N., Goetsch L. (2009) Int. J. Cancer 124, 2281–2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kirkpatrick D. S., Denison C., Gygi S. P. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 750–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Munshi S., Hall D. L., Kornienko M., Darke P. L., Kuo L. C. (2003) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 1725–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Phu L., Izrael-Tomasevic A., Matsumoto M. L., Bustos D., Dynek J. N., Fedorova A. V., Bakalarski C. E., Arnott D., Deshayes K., Dixit V. M., Kelley R. F., Vucic D., Kirkpatrick D. S. (2011) Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 10, 10.1074/mcp.M110.003756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hunter T. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 730–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Monami G., Emiliozzi V., Morrione A. (2008) J. Cell. Physiol. 216, 426–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zotti T., Uva A., Ferravante A., Vessichelli M., Scudiero I., Ceccarelli M., Vito P., Stilo R. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22924–22933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chastagner P., Israël A., Brou C. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7, 1147–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Al-Hakim A. K., Zagorska A., Chapman L., Deak M., Peggie M., Alessi D. R. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang F., Kirkpatrick D., Jiang X., Gygi S., Sorkin A. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 737–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wu J., Li W., Craddock B. P., Foreman K. W., Mulvihill M. J., Ji Q. S., Miller W. T., Hubbard S. R. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 1985–1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]