Abstract

Objectives

Cognitive dysfunction is common in patients with advanced, life-threatening illness and can be attributed to a variety of factors (e.g., advanced age, opiate medication). Such dysfunction likely affects decisional capacity, which is a crucial consideration as the end of life approaches and patients face multiple choices regarding treatment, family, and estate planning. This study examined the prevalence of cognitive impairment and its impact on decision-making abilities among hospice patients with neither a chart diagnosis of a cognitive disorder nor clinically apparent cognitive impairment (e.g., delirium, unresponsiveness).

Design

110 participants receiving hospice services completed a one-hour neuropsychological battery, a measure of decisional capacity, and accompanying interviews.

Results

In general, participants were mildly impaired on measures of verbal learning, verbal memory, and verbal fluency; 54% of the sample was classified as having significant, previously undetected cognitive impairment. These individuals performed significantly worse than the other participants on all neuropsychological and decisional capacity measures, with effect sizes ranging from medium to very large (0.43–2.70). A number of verbal abilities as well as global cognitive functioning significantly predicted decision-making capacity.

Conclusions

Despite an absence of documented or clinically obvious impairment, more than half of the sample had significant cognitive impairments. Assessment of cognition in hospice patients is warranted, including assessment of verbal abilities that may interfere with understanding or reasoning related to treatment decisions. Identification of patients at risk for impaired cognition and decision-making may lead to effective interventions to improve decision-making and honor the wishes of patients and families.

Keywords: dementia, delirium, hospice, neuropsychology, cognitive impairment, decision-making, palliative care

Impaired cognition is common in the palliative care population; rates of delirium range from 14–85% and up to 90% of patients demonstrate some sort of cognitive impairment before death (1–2). In addition, over 11% of patients receiving hospice care annually have a primary hospice diagnosis of advanced dementia (3), which includes impaired cognition as part of the diagnostic criteria. A pilot study from our group (4) demonstrated that among thirty acute care hospice inpatients with no chart diagnosis of dementia or other cognitive impairment, one-third met the cognitive criteria for a diagnosis of dementia, exhibiting impairments in verbal learning, verbal memory, verbal reasoning, and/or verbal fluency.

The etiology of cognitive dysfunction in seriously ill patients, including those with dementia, is likely multifaceted. Known risk factors include treatment with chemotherapy (5) or radiation therapy (6), opiate medication use (7–8), and the illness itself (e.g., cancer, dementia) (9). Because of these plausible sources of cognitive impairment in palliative care patients and the potential reversibility of delirium (10–11), careful attention to cognitive functioning in patients with advanced, life-threatening illness is warranted. In addition, there are enormous considerations associated with the final phase of a person’s life (e.g., estate planning, advance directives, achieving end of life goals, spending time with family and friends), further highlighting the need for cognitive assessment in this population.

An important consequence of impaired cognition is impaired decision-making (12–13). In the small number of published studies of patients with life-threatening illness, decision-making capacity and neuropsychological performance have been shown to be related. For example, one study found that patients with malignant glioma demonstrated impaired medical decision-making capacity relative to healthy controls, and that measures of verbal memory and verbal fluency predicted scores on measures of understanding and reasoning abilities on an instrument evaluating capacity to consent to treatment (14). In another sample of patients with advanced illness, poorer performance on the Mini Mental State Examination (15) was significantly related to poorer capacity to provide informed consent (16). Studies including patients without advanced illness but with cognitive impairment or dementia have yielded similar results: one study found that medical decision-making capacity in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment was significantly more impaired than in healthy controls, and that the ability to understand consent information significantly declined over time (17). Similarly, neuropsychological performance in attention, logical memory, language, and executive function significantly predicted capacity for treatment decisions in community participants with mild to moderate dementia (18).

Despite the profound implications of decisional capacity and associated cognitive decline in patients with advanced, life-threatening illness, there is no single clinically accepted method for assessing decision-making capacity (19–20). The most widely cited model formulates decisional capacity as including four components: 1) understanding information relevant to the decision, 2) appreciating the information (applying the information to one’s own situation), 3) reasoning with the information, and 4) expressing a consistent choice (21). In spite of this model, consistent formal or informal, structured or unstructured assessment of decisional capacity has remained elusive (22). The issue of decisional capacity and its determination in hospice patients is not well understood, prompting a need for more targeted exploration. Existing instruments to evaluate decisional capacity are research tools rather than clinical tools and are frequently burdensome and not clinically useful, highlighting the need for development of clinically relevant instruments to assess decisional capacity in potentially cognitively impaired populations.

Given these limited and variable conclusions about the precise relationship between cognition and decision-making in the hospice population, further investigation is needed to examine not only the prevalence and types of cognitive impairment in hospice care patients, but also the relationship of cognitive impairment to decision-making abilities. This study was designed to evaluate cognition and decision-making capacity in patients receiving either inpatient or home hospice care and who had no clinically obvious cognitive impairment and no chart diagnosis of a cognitive disorder. We hypothesized that 1) at least half of participants would demonstrate significant cognitive impairment, 2) those with significant cognitive impairment would perform worse on cognitive and decisional capacity measures relative to those without such impairment, and 3) cognitive impairment would be associated with diminished decision-making capacity.

METHOD

Participants

Participants included 110 patients receiving palliative care services from San Diego Hospice and the Institute for Palliative Medicine (SDHIPM). Fifty-five were recruited from an acute-care inpatient unit and 55 were receiving hospice care at home. Neuropsychological performance characteristics from thirty of the participants in this sample were included in pilot analyses published in 2008 (4). On average, participants were 70 years old and had completed 14 years of education; 53 participants (48%) were men, and 49 (45%) were married. The majority of the sample was Caucasian, and most were diagnosed with advanced cancer.

Procedure

This study was approved by SDHIPM and University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Boards. All patients who enrolled in SDHIPM services were screened for eligibility by a trained research nurse; participants who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. Patients were excluded if they: a) were under 18 years of age, b) did not speak English fluently, c) could not stay awake for at least one hour, d) had a diagnosis of dementia or delirium documented in the medical record, e) demonstrated clinically obvious cognitive impairment observed by the primary care provider, palliative care team, or the trained research nurse (e.g., disorientation, incoherence, unresponsiveness), f) had a history of neurological disease or injury (e.g., stroke, traumatic brain injury), or g) had other known cognitive impairment (e.g., mental retardation). Patients’ physical symptoms (e.g., pain) were sufficiently controlled to enable testing. All measures and interviews were administered by a trained research assistant in the location of the patient’s care (i.e., bedside at SDHIPM acute-care inpatient unit or at the patient’s home); rest breaks were provided as requested by the participant.

Measures

Assessment instruments were selected to evaluate the cognitive domains necessary to attend to, learn, reason with, and recall verbal information, with the intention of closely representing the abilities required for a realistic doctor-patient treatment discussion. The instruments were also chosen to reduce patient burden and minimize reliance on motor skills other than speaking. Because the primary purpose of the study was to evaluate cognitive impairment in general rather than to make specific DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of the type of cognitive impairment, structured diagnostic interviews or other diagnostic assessments (e.g., delirium versus dementia) were not employed. Participants also completed a measure of decision-making capacity and a self-report questionnaire assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression. The neuropsychological test battery included the following domains and measures:

Premorbid intellectual functioning (Wide Range Achievement Test - 3; WRAT-3; reading subtest; estimated premorbid verbal IQ) (24)

Global cognitive functioning (Mini Mental State Examination; MMSE; total correct) (15)

Attention and working memory (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – III; WAIS-III; Digit Span total correct Scaled Score) (25)

Verbal learning (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised; HVLT-R; total immediate recall T-score) (26)

Verbal memory (HVLT-R; total delayed recall T-score) (26)

Verbal reasoning (Delis-Kaplan Executive Functioning System; DKEFS; Word Context Test total consecutively correct Scaled Score) (27)

Verbal fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Test; COWAT; FAS total correct T-score and animals total correct T-score) (28–29)

Psychiatric symptom severity was measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; total anxiety score and total depression score) (30), which has been validated in palliative care populations (31).

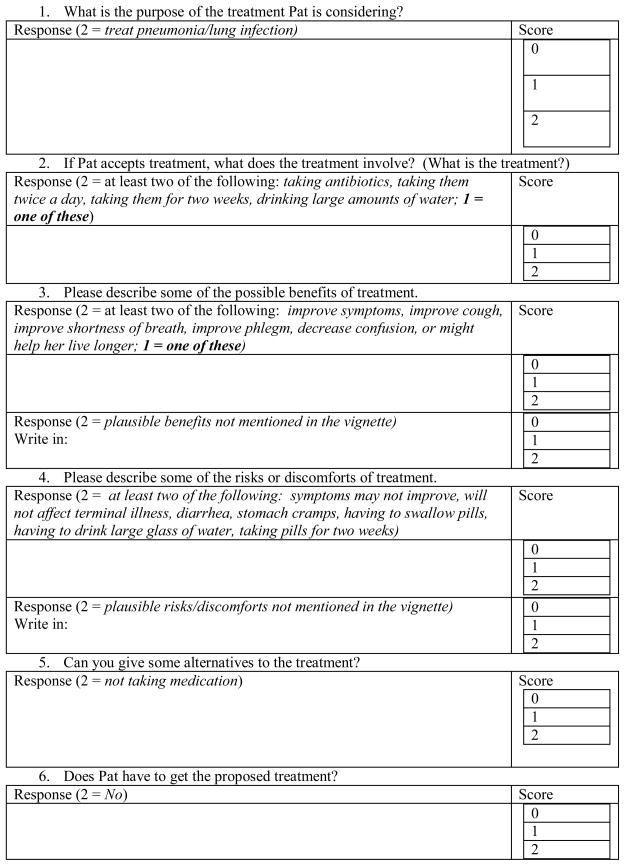

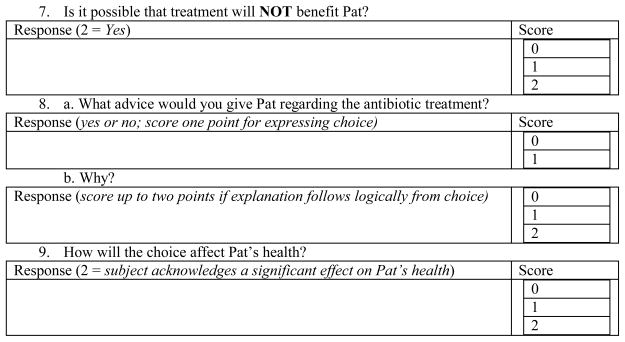

Decision-making capacity was measured with a modified version of the UCSD Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC) (32). The UBACC was originally developed for assessment of capacity to consent to research participation, but for the present study we modified the item content as appropriate for a treatment consent context (see Appendix A). Also, whereas the original UBACC is tailored to a decision specific to the individual, in the present study we used a standardized hypothetical but ecologically valid and relevant treatment scenario for all subjects: a patient with an advanced, life-threatening illness and pneumonia who must decide whether or not to be treated with antibiotics. The resulting “UBACC-T” was reviewed and piloted by the research team to assess acceptability and readability to interviewees, and then revised accordingly. Following presentation of the hypothetical scenario each patient was interviewed with the UBACC-T, consisting of ten questions worth 19 points: two points were awarded for a plausible answer, one point was awarded for a partially plausible answer, and zero points were awarded for a non-plausible answer, except for one question which was awarded only a one or a zero. To minimize the effect of recall on performance on this scale, the participant silently read the scenario as the examiner read it aloud and was permitted to refer to the printed vignette while answering questions.

Data Analyses

All variables were normally distributed. T-scores were scaled such that a score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 characterized the normal population, and higher scores indicated better performance. Similarly, scaled scores were scaled such that a score of 10 and a standard deviation of three characterized the normal population, and higher scores indicated better performance. To enable comparisons between testing sites, demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological features of the inpatient and homecare groups were analyzed with t-tests for independent samples and chi-square tests. A frequency count yielded the number of participants with “significant cognitive impairment,” which was defined using a portion of the DSM-IV-TR (23) criteria for dementia: “multiple cognitive deficits that include memory impairment and at least one of the following cognitive disturbances: aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or a disturbance in executive functioning” (page 148). For this study, ‘impairment’ was defined as a t-score lower than 40 or a scaled score lower than seven in a measured domain; participants were considered to have “significant cognitive impairment” if they were impaired in verbal memory and at least one other measured domain. To investigate whether medications affected cognitive performance, the total amount of any opiate, steroid, or benzodiazepine received over the 48 hours prior to testing for each inpatient subject was obtained from the medicine administration record and converted to total dosage equivalents (mg) of morphine (n=36), dexamethasone (n=27), and lorazepam (n=13). Medication data was not available from homecare patient records. Pearson correlations examined the relationships between total dosage equivalent received of each of the three medication classes over 48 hours prior to testing and performance on neuropsychological and decisional capacity measures.

Differences between participants who met the criteria for “significant cognitive impairment” and those who did not were analyzed with t-tests for independent samples and chi-square tests. Equal variances were not assumed for any t-test comparison in which Levene’s test for equality of variances was significant. To estimate the magnitude of effects, Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated comparing the group that met criteria for significant cognitive impairment and the group that did not on neuropsychological test performance (.20=small effect; .50=medium effect; .80=large effect) (33).

Pearson correlations were calculated to investigate the relationship between decision-making capacity and neuropsychological performance, followed by separate hierarchical linear regressions including each significant correlate as a predictor. Because education, minority ethnicity, and testing site were found to be significantly related to decisional capacity, these three variables were entered in step 1 of the regression, followed by the neuropsychological variable in step 2. Alpha for significance was set at 0.05 and all tests were two-tailed. Data were analyzed using PASW Statistics for Windows (Version 18).

RESULTS

Between 2006 and 2010, 4732 patients were screened; 4377 were not eligible and 242 were not interested in participating. The most common reasons for exclusion were altered mental status due to imminent death (50%), history of stroke or seizures (14%), inability to sustain wakefulness/verbal unresponsiveness (10%), or diagnosed dementia (10%). Cognitive performance for inpatient and homecare patients is presented in Table 1. Participants in both groups demonstrated average premorbid verbal intellectual functioning but were mildly impaired on a measure of verbal memory; both groups also reported “minimal” anxiety and depression as measured by the HADS. Inpatients were significantly older, more likely to be of minority ethnicity, and more likely to be married than homecare participants, and they lived significantly fewer days between testing and death; inpatients also performed significantly worse in virtually all measured cognitive domains (Table 1). Despite numerous differences in cognitive performance, these groups did not differ in rates of significant cognitive impairment (Table 1). Therefore, the groups were combined for the remaining analyses. Fifty-nine participants, 54%, (33 inpatient; 26 homecare) were found to have significant cognitive impairment (i.e., impairment in memory and at least one other cognitive domain). Opiate (morphine) and steroid (dexamethasone) dose equivalents were not significantly related to performance on any measure; for the small number of inpatients who were administered benzodiazepine, higher benzodiazepine (lorazepam) dose was significantly associated with better verbal fluency (COWAT animals t-score; n=13; r=.70; p=.008).

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Inpatient and Homecare Groups

| Inpatient (n=55) | Homecare (n=55) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (sd) or % | mean (sd) or % | t or χ2 | df | p | |

| Demographic variables | |||||

| Age, years | 64.2 (14.9) | 75.3 (13.7) | −4.03 | 108 | <.001 |

| Education, years | 13.3 (2.9) | 13.9 (2.9) | −1.05 | 107 | .296 |

| % Male | 44% | 53% | 0.91 | 1 | .340 |

| % Minority ethnicity | 16% | 0.04% | 4.95 | 1 | .026 |

| % Married | 55% | 35% | 4.45 | 1 | .035 |

| Clinical variables | |||||

| % Cancer diagnosis | 69% | 58% | 1.41 | 1 | .235 |

| Days lived between testing and death | 52.5 (63.7) | 95.2 (87.1) | −2.53 | 78 | .013 |

| HADS anxiety total score | 7.8 (5.0) | 5.6 (3.9) | 1.75 | 66 | .086 |

| HADS depression total score | 8.2 (5.6) | 6.2 (3.3) | 1.75 | 66 | .084 |

| Neuropsychological variables | |||||

| MMSE total score | 23.4 (3.2) | 25.2 (2.6) | −3.37 | 106 | .001 |

| WRAT-3 estimated premorbid verbal IQ | 100.7 (10.4) | 103.8 (8.9) | −1.69 | 107 | .093 |

| HVLT-R total immediate recall t-score | 34.2 (12.1) | 40.3 (11.3) | −2.75 | 108 | .007 |

| HVLT-R delayed recall t-score | 34.9 (13.1) | 37.4 (11.0) | −1.06 | 107 | .290 |

| WAIS-III digit span total scaled score | 7.8 (2.7) | 9.7 (2.8) | −3.72 | 108 | <.001 |

| DKEFS Word Context total consecutively correct scaled score | 6.0 (3.5) | 9.2 (3.5) | −4.77 | 104 | <.001 |

| COWAT FAS t-score | 35.1 (9.3) | 44.0 (10.7) | −4.62 | 107 | <.001 |

| COWAT animals t-score | 35.1 (10.8) | 43.0 (11.1) | −3.75 | 107 | <.001 |

| UBACC-T total score | 13.9 (3.5) | 15.9 (2.2) | −3.10 | 46.9 | .003 |

| ”Significant Cognitive Impairment” | 61% | 47% | 2.10 | 1 | .147 |

Note. Significant differences are indicated in bold font. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MMSE=Mini Mental State Exam; WRAT-3=Wide Range Achievement Test, Third Edition; HVLT-R=Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised; WAIS-III=Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition; DKEFS=Delis Kaplan Executive Function System; COWAT=Controlled Oral Word Association Test; UBACC-T=UCSD Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent for Treatment

No demographic or clinical differences, including medication dosage, were found between participants with and without significant cognitive impairment (Table 2). Although participants with significant cognitive impairment had statistically significantly lower premorbid IQ, their mean score was solidly in the average range and the difference between the groups was only 4 IQ points. Therefore, neuropsychological differences between the two groups are not likely to be due to pre-existing differences in verbal intelligence. Those with significant cognitive impairment performed significantly worse than those without such impairment on all neuropsychological measures, with effect sizes ranging from medium (0.43) to very large (2.70; all ps ≤ 0.05; see Table 2). Mean performance on the UBACC-T significantly differed between these groups, though the difference in scores was only about two points (p<0.001; d=0.90; Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic, Clinical, and Neuropsychological Characteristics of the Cognitive Impairment Groups

| “Significant Cognitive Impairment” (n=59) | No “Significant Cognitive Impairment” (n=50) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (sd) or % | mean (sd) or % | t or χ2 | df | p | Cohen’s d | |

| Demographic variables | ||||||

| Age, years | 68.4 (17.8) | 71.2 (16.2) | 0.94 | 107 | 0.351 | -- |

| Education, years | 13.4 (3.1) | 13.8 (2.5) | 0.63 | 106 | 0.530 | -- |

| % Male | 56 | 40 | 2.75 | 1 | 0.097 | -- |

| % Minority ethnicity | 14 | 6 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.192 | -- |

| % Married | 46 | 42 | 2.32 | 3 | 0.508 | -- |

| Clinical variables | ||||||

| % Cancer diagnosis | 60 | 69 | 1.16 | 1 | 0.282 | -- |

| % Inpatient | 56 | 42 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.147 | -- |

| Days to death | 64.9 (79.5) | 77.7 (72.8) | 0.73 | 77 | 0.468 | -- |

| HADS anxiety total score | 5.4 (3.6) | 6.6 (4.6) | 1.09 | 66 | 0.280 | -- |

| HADS depression total score | 6.5 (3.9) | 6.7 (4.0) | 0.13 | 66 | 0.898 | -- |

| Morphine dose equivalent (mg) | 1265.9 (1478.2) | 917.7 (1652.6) | −0.69 | 37 | 0.492 | -- |

| Dexamethasone dose equivalent (mg) | 28.3 (18.8) | 25.6 (13.8) | −0.43 | 28 | 0.672 | -- |

| Lorazepam dose equivalent (mg) | 3.8 (3.4) | 4.9 (2.3) | 0.59 | 11 | 0.571 | -- |

| Neuropsychological variables | ||||||

| MMSE total score | 23.4 (3.2) | 25.5 (2.3) | 3.83 | 105 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| WRAT-3 estimated premorbid verbal IQ | 100.3 (10.9) | 104.4 (7.8) | 2.23 | 102.6 | 0.028 | 0.43 |

| HVLT-R total immediate recall t-score | 28.4 (7.2) | 47.8 (7.3) | 13.94 | 107 | <0.001 | 2.70 |

| HVLT-R delayed recall t-score | 27.4 (6.7) | 46.5 (8.2) | 13.37 | 107 | <0.001 | 2.60 |

| WAIS-III digit span total scaled score | 7.9 (2.6) | 9.8 (2.9) | 3.58 | 107 | 0.001 | 0.70 |

| DKEFS Word Context total consecutively correct scaled score | 5.8 (3.2) | 9.7 (3.5) | 5.92 | 104 | <0.001 | 1.18 |

| COWAT FAS t-score | 36.1 (9.9) | 44.1 (10.4) | 4.07 | 106 | <0.001 | 0.80 |

| COWAT animals t-score | 34.8 (10.2) | 44.5 (11.0) | 4.76 | 106 | <0.001 | 0.93 |

| UBACC-T total score | 14.0 (3.1) | 16.4 (2.1) | 4.31 | 78.3 | <0.001 | 0.90 |

Note. One participant was not able to complete the verbal memory measure and was thus excluded from group classification. Significant differences are indicated in bold font. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MMSE=Mini Mental State Exam; WRAT-3=Wide Range Achievement Test, Third Edition; HVLT-R=Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised; WAIS-III=Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition; DKEFS=Delis Kaplan Executive Function System; COWAT=Controlled Oral Word Association Test; UBACC-T=UCSD Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent for Treatment

Pearson correlations and hierarchical linear regressions examining the relationship between decision-making and demographic features as well as cognitive abilities demonstrated that worse performance on the UBACC-T was significantly correlated with less education (n=88; r=.35; p=.001), minority ethnicity (minority M=11.14; SD=3.49; Non-hispanic Caucasian M=15.49; SD=2.58; t=4.17; df=86; p<.001), and inpatient status (inpatient M=13.85; SD=3.47; homecare M=15.93; SD=2.15; t=−3.10; df=46.93; p=.003). After first accounting for variance attributable to education, ethnicity, and inpatient/outpatient status by forced entry into the model, global cognitive functioning, verbal learning, verbal memory, verbal reasoning, and verbal (semantic) fluency significantly predicted decision-making capacity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Regression Controlling for Education, Minority Status, and Inpatient/Outpatient Status

| Beta | t | p | Semi-partial correlation | R square | R square change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE total score | .364 | 4.11 | <.001 | .340 | .433 | .317 |

| WRAT-3 estimated premorbid verbal IQ | .191 | 1.83 | .071 | .163 | .344 | .026 |

| HVLT-R total immediate recall t-score | .399 | 4.81 | <.001 | .386 | .466 | .149 |

| HVLT-R delayed recall t-score | .360 | 4.27 | <.001 | .353 | .438 | .125 |

| WAIS-III digit span total scaled score | .175 | 1.79 | .077 | .159 | .343 | .025 |

| DKEFS Word Context total consecutive correct scaled score | .420 | 4.50 | <.001 | .368 | .457 | .136 |

| COWAT FAS t-score | .241 | 2.55 | .013 | .222 | .367 | .049 |

Note. Each regression equation included education, minority status, inpatient/outpatient status, and a single neuropsychological variable, so the degrees of freedom for each equation were four. Significant differences are indicated in bold font. MMSE=Mini Mental State Exam; WRAT-3=Wide Range Achievement Test, Third Edition; HVLT-R=Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised; WAIS-III=Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition; DKEFS=Delis Kaplan Executive Function System; COWAT=Controlled Oral Word Association Test

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated important and understudied factors in hospice care: cognition and decision-making capacity in patients receiving hospice care and who had no chart diagnosis of a cognitive disorder and no clinically obvious cognitive impairment (e.g., disorientation, incoherence, unresponsiveness). In general, it appears that patients receiving inpatient care are more cognitively impaired than their homecare counterparts, possibly because they are nearer to death or very ill with symptoms that may have interfered with cognition. As hypothesized, however, these results indicate that regardless of inpatient/outpatient status, more than half (54%) of hospice patients with no known or obvious cognitive impairment nonetheless manifest significant impairments in a variety of cognitive domains. The results also suggest that this cognitive impairment may not be attributable to mere medication effects, as there was no significant relationship between opiate/steroid medication dosage and neuropsychological performance, at least in patients receiving inpatient hospice care.

With regard to the relationship between neuropsychological performance and decisional capacity, participants with significant cognitive impairment performed significantly worse on the decision-making measure than those without such impairment. In addition, these results suggest that performance on measures of general cognitive function, verbal learning, verbal memory, verbal reasoning, and verbal (semantic) fluency predict decision-making capacity.

These findings are consistent with previous research indicating high rates of cognitive impairment in the palliative care population (1). It appears that, consistent with the published literature (5–9), the sources of cognitive impairment in hospice patients are numerous and could be cumulative as the illness advances. In addition, the results from this larger sample (which includes participants from our previous published results) indicate a greater frequency of cognitive impairment than those reported previously (4). Our results also extend previous findings that verbal abilities predict decisional capacity (14), as verbal learning, verbal memory, verbal reasoning, and verbal fluency were among the significant predictors of decisional capacity. It should be noted that only a small percentage of those screened met inclusion criteria for the study, indicating that a large proportion of hospice patients have a clinical presentation that interferes with research participation and testing. Thus, the overwhelming majority of patients receiving hospice care have clinically obvious and/or documented cognitive impairments. These clinical features likely translate to lack of decision-making capacity, such that this study seriously underestimates the prevalence of diminished cognitive ability and decisional capacity in all patients receiving hospice care.

Limitations of the study include lack of longitudinal information regarding cognitive decline and its impact on psychosocial functioning, which precluded formal diagnoses of dementia or other cognitive disorders for participants who demonstrated significant cognitive impairment. Further investigations are needed to yield more precise diagnoses. In addition, our criteria for significant cognitive impairment may have excluded those with more subtle, subclinical cognitive dysfunction. However, the correlational analysis of cognitive performance and decisional capacity incorporated all levels of performance and would have captured this subclinical cognitive impairment that could affect decision-making ability. Although we explored a number of factors hypothesized to contribute to impaired cognition (e.g., medication, psychiatric symptoms), the negative findings suggest that there are other contributing factors that were not measured, including sequelae of the advanced illness itself. Further, the measure for decisional capacity, the UBACC-T, is a newly developed instrument and its psychometric properties are not yet established; our results should therefore be interpreted with caution as the UBACC-T is not a validated instrument. Follow-up studies should include examination of the reliability and validity of the UBACC-T, and perhaps include a known valid instrument for decision-making to assess concurrent validity (e.g., the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool – Treatment; MacCAT-T) (34). Also, the scenario presented in the UBACC-T was hypothetical (albeit relevant), so it may not fully generalize to real-world decisions in which patients are invested and likely to pay close attention. Despite these limitations, this study augments the existing literature on cognitive ability and decision-making capacity in patients receiving hospice care. Participants were selected through rigid adherence to exclusion criteria in an effort to create the most cognitively “normal” appearing sample possible based on clinical judgment via usual hospice care. Although the vast majority of screened patients were excluded, these results indicate that of those who would likely be considered cognitively intact based on clinical impression, over half exhibit significant cognitive impairment.

Because a large proportion of this sample demonstrated cognitive impairment and these deficits were found to be related to poorer decisional capacity, there may be implications for treatment. Greater attention could be paid to cognition in hospice patients, including impairment in verbal abilities (learning, memory, reasoning, fluency) that could contribute to poor communication among patients, providers, and family members, as well as impaired understanding or reasoning related to treatment decisions, including medication or other treatment adherence. Clinicians should be cognizant of the strong potential for impaired cognition and decision-making capacity, particularly in patients who otherwise appear intact. Assessing capacity can be done at the bedside with or without structured instruments, but needs to be considered especially when high stakes decisions are at hand. Clinicians can identify patients at risk for impaired decision-making and ameliorate impaired capacity when possible. Ensuring that family or other interested parties are enlisted to help in decision-making is a good option, especially early in the illness trajectory. Previous research has demonstrated that more than 75% and perhaps greater than 90% of patients near the end of life want a family member to help them make decisions with the doctor about their care (35–36). Many clinicians favor advance care planning because it facilitates discussion of end of life issues between patients, physicians, and caregivers, and provides an opportunity to respect a patient’s predetermined wishes even if the patient lacks decision-making capacity at some point in the future (37). Advance care planning may also decrease stress in the surrogate decision maker (38), however, many individuals with cognitive impairment still do not complete advance care planning, raising the possibility that patients and families need more information or counseling related to understanding the goal of advance directives and the options they provide (39).

Patients who have difficulty understanding or appreciating information may benefit from brief interventions like multiple learning trials and summaries of information, receiving information through multiple methods (e.g. hearing, seeing), and being provided ample time and opportunity to paraphrase what was explained and to review information again (40). Further research on methods to improve the identification of cognitive and decisional impairments at the end of life are needed, as the stakes of advanced, life-threatening illnesses for an individual, their family, and society in general can be immense. Armed with the knowledge that hospice patients often exhibit cognitive deficits and that such deficits could contribute to impaired decisional capacity, palliative care clinicians can initiate interventions to improve cognitive function and/or decisional capacity to enhance end of life communication and outcomes for both patients and families.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carlene Gibbons, Linda Lloyd, Laura Chambers, Karen Lamphere, Rosene Pirrello, and Betty Richardson for their assistance with this project.

This work was supported, in part, by the National Palliative Care Research Center, the John A. Hartford Center of Excellence in Geriatric Psychiatry at UCSD, Award Number K23MH091176, from the National Institute of Mental Health, and by donations from the generous benefactors of the education and research programs at the Institute for Palliative Medicine. Additional support includes NIMH Award Number RO1MH064722 and NIA Award Number RO1AG028827.

Appendix A. UCSD Brief Assessment for Capacity to Consent to Treatment

This is completely hypothetical (imaginary).

Imagine you have a good friend named Pat. Pat has a terminal illness and is receiving hospice care at her home. Her doctors think she has several weeks to several months to live. She would like to stay at home until she dies. It is difficult for Pat to swallow food or fluids.

Pat has had a lung infection (pneumonia) several times, and has been diagnosed with pneumonia again. She wants your advice. Pat needs to decide whether she should take antibiotics to treat the pneumonia or not.

Pat says that when she gets pneumonia, she coughs up phlegm, feels short of breath, and feels confused.

If Pat DOES take the antibiotics, the doctors say that there is about a 50% (1 in 2) chance that her lung infection will get better.

The antibiotics might help Pat live longer, but will not change the fact she has a terminal illness. More than 10% of people (1 in 10) treated with antibiotics get bad diarrhea and stomach cramps. The antibiotic pills are large and would have to be swallowed twice a day with a large glass of water for two weeks.

If she does NOT take the antibiotics, she might die from the pneumonia.

Pat asks you, should she take the antibiotics?

Modified UCSD Brief Assessment for Capacity to Consent (UBACC-T)

|

Footnotes

No Disclosures to Report

References

- 1.Breitbart W, Bruera E, Chochinov H, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes and psychological symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:131–141. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00075-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hjermstad MJ, Loge JH, Kaasa S. Methods for assessment of cognitive failure and delirium in palliative care patients: implications for practice and research. Palliat Med. 2004;18:494–506. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm920oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. [Accessed January 7, 2011.];NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America [NHPCO online] 2010 September; Available at: http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/Hospice_Facts_Figures_Oct-2010.pdf.

- 4.Irwin SA, Zurhellen CH, Diamond LC, et al. Unrecognised cognitive impairment in hospice patients: a pilot study. Palliat Med. 2008;22:842–847. doi: 10.1177/0269216308096907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, et al. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trail. Cancer. 2004;100:2292–2299. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa DD. Neurocognitive function in brain tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:232–239. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherrier MM, Amory JK, Ersek M, et al. Comparative cognitive and subjective side effects of immediate-release oxycodone in healthy middle-aged and older adults. J Pain. 2009;10:1038–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood MM, Ashby MA, Somogyi AA, et al. Neuropsychological and pharmacokinetic assessment of hospice inpatients receiving morphine. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira J, Hanson J, Bruera E. The frequency and clinical course of cognitive impairment in patients with terminal cancer. Cancer. 1997;79:835–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centeno C, Sanz A, Bruera E. Delirium in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2004;18:184–194. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm879oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:786–794. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer BW, Savla GN. The association of specific neuropsychological deficits with capacity to consent to research or treatment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:1047–1059. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707071299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer BW, Savla GN, Harmell AL. Capacity to decide about healthcare, in Civil capacities in clinical neuropsychology: Research findings and practical applications. Demakis GJ. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triebel KL, Martin RC, Nabors LB, et al. Medical decision-making capacity in patients with malignant glioma. Neurology. 2009;73:2086–2092. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67bce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination user’s guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorger BM, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Decision-making capacity in elderly, terminally ill patients with cancer. Behav Sci Law. 2007;25:393–404. doi: 10.1002/bsl.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okonkwo OC, Griffith HR, Copeland JN, et al. Medical decision-making capacity in mild cognitive impairment: a 3-year longitudinal study. Neurology. 2008;71:1474–1480. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334301.32358.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurrera RJ, Moye J, Karel MJ, et al. Cognitive performance predicts treatment decisional abilities in mild to moderate dementia. Neurology. 2006;66:1367–1372. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210527.13661.d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, et al. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instruments. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1323–1334. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones RC, Holden T. A guide to assessing decision-making capacity. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:971–975. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.12.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: A guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:237–243. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson GS. WRAT-3 manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. (WAIS-III) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised. Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. DKEFS examiner’s and technical manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benton AL, Hamsher KS. Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa City, IA: AJA Associated; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gladsjo JA, Schuman CC, Evans JD, et al. Norms for letter and category fluency: demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1999;6:147–178. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd-Williams M, Spiller J, Ward J. Which depression screening tools should be used in palliative care? Palliat Med. 2003;17:40–43. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm664oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, et al. A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:966–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: A clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415–1419. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.11.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold RM, Kellum J. Moral justifications for surrogate decision making in the intensive care unit: implications and limitations. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S347–S353. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065123.23736.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SH, Kjervik D. Deferred decision making: Patients’ reliance on family and physicians for CPR decisions in critical care. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12:493–506. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne817oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavalieri TA. Ethical issues at the end of life. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2001;101:616–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: The effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:335–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garand L, Dew MA, Lingler JH, et al. Incidence and predictors of advance care planning among persons with cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;00:1–9. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faebef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunn LB, Jeste DV. Enhancing informed consent for research and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:595–607. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]