Abstract

Medicine is rapidly applying exome and genome sequencing to the diagnosis and management of human disease. Somatic mosaicism, however, is not readily detectable by these means, and yet it accounts for a significant portion of undiagnosed disease. We present a rapid and sensitive method, the Continuous Distribution Function as applied to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data, to quantify somatic mosaicism throughout the genome. We also demonstrate application of the method to novel diseases and mechanisms.

1. Introduction

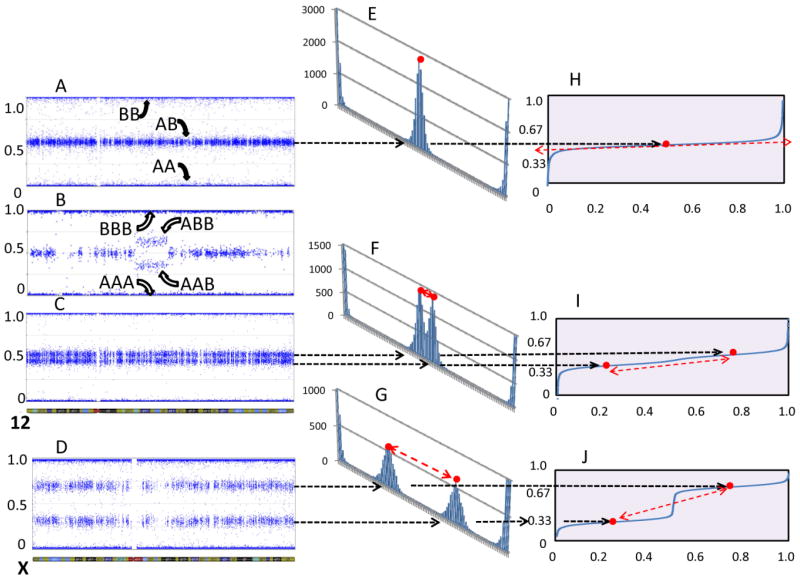

Somatic mosaicism, including whole chromosome aneuploidy, segmental aneuploidy [Youssoufian and Pyeritz, 2002; Conlin et al., 2010] and uniparental disomy [1], play a crucial role in determining the phenotype of genetic disorders [2]. Since mosaicism often occurs differentially among tissues [2, 3], its ascertainment can be challenging [4-6]. Methods of detection have evolved from the gross counting of Giemsa-stained metaphase chromosomes to locus-by-locus analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data using B allele frequency plots [7]. SNP-based oligonucleotide arrays are run under a single hybridization condition, which limits the dynamic range at each locus to simple dizygous genotyping calls, i.e., AA, AB or BB (Fig. 1A). With duplications, however, there are four equally spaced genotypes, AAA, AAB, ABB and BBB [7, 8], and the two heterozygous states appear as a split of the middle (heterozygous) fluorescence intensity on a B allele frequency plot (Fig. 1B). Mosaic mixtures of aneuploid cells give fractional spacing of these states and yield unequally spaced data in these plots [9].

Fig. 1.

B allele plots for duplication, normal dizyogous chromosome (a), an interstitial duplication (b), a trisomy/monosomy mosaic (c) and a monosomy/disomy chromosome (d). Binned counts for SNPs with B allele frequency values for 200 bins from 0 to 1.0, summed along the entire chromosome length e corresponding to a, f corresponding to c, g corresponding to d. Note that the non-homozygous regions of the binned counts form a quasi-normal distribution with a single mode for normal, and overlapping and non-overlapping bimodal peaks for the mosaic examples. Continuous distribution functions are shown for the normal h, and respective mosaic examples i, j.

Even in normal dizgyous experimental data, the fluorescent intensities are displaced from their theoretical B allele frequencies of 0.0, 0.5 and 1.0 by many factors, including variations in the chemistry and methodology of fluorescent hybridizations and PCR amplifications. As a result, SNP array fluorescence intensities represent only quasi-normalized stochastic data. For such data, the use of a Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) is superior to simple averaging to detect a central tendency [10]. An implementation of this is the Distribution Analysis by Fitting Integrated Probabilities (DANFIP), which uses an inverse CDF fit to deconvolve the central tendencies of overlapping distributions in quasi-normalized data [11]. The B-allele frequency in a nonhomozygous region of SNP array data reflects contributions of the central tendencies of two distributions, i.e., the degree of mosaicism. Hence, DANFIP provides an ideal method of data transformation to determine the percent mosaicism.

To test this hypothesis, we applied the DANFIP method to SNP data from patients enrolled in the NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program (UDP) or other rare disease studies. The analysis detected unsuspected full and partial chromosomal mosaicism with remarkable sensitivity, creating numerous diagnostic and research opportunities and highlighting a new disease mechanism.

2. Results

2.1 DANFIP detects mosaicism with sensitivity greater than pipetting accuracy

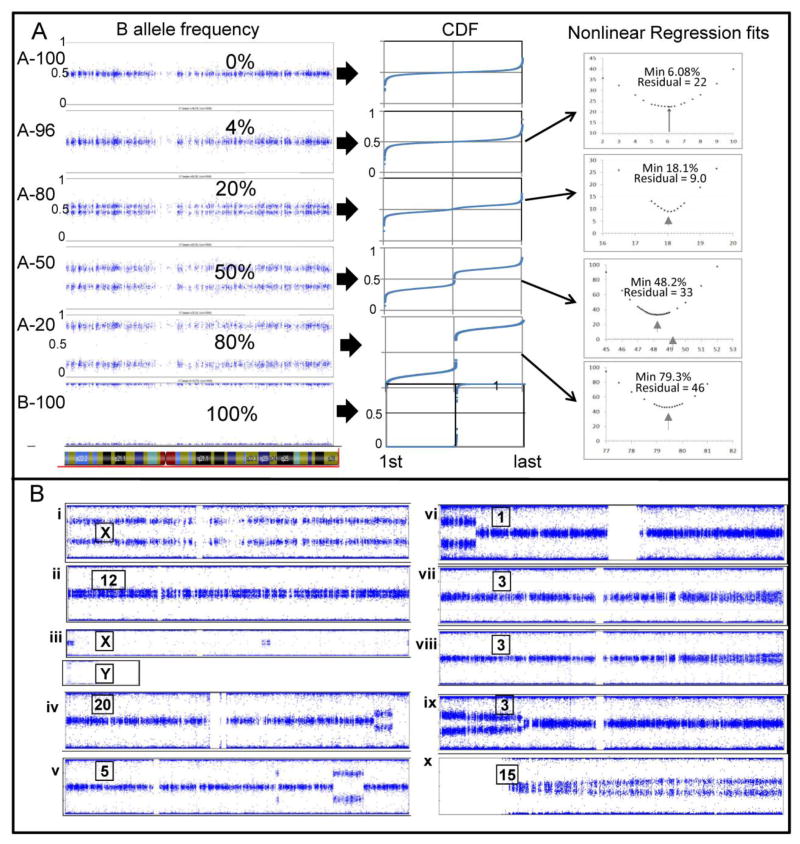

To assess the DANFIP method’s sensitivity to quantify mosaicism, we tested a series of DNA mixtures from a mother and son, a model for whole X chromosome mosaicism (Supp. Manual; Fig. 4A). The CDF regression quantified this artificial mosaicism to within 0.1% across the entire range of values from 4% to 80% monosomy/disomy mosaicism; the fitting of the X chromosome mixing experiment (“mosaic”) data to control disomy X data using the monosomy/disomy model (Fig. 3) is demonstrated visually in the supplemental video. The regression minimum approximated the percent mosaicism introduced by the artificial monosomy to within pipetting error. All nonlinear regressions converged successfully, and repetitions starting with different initial seeds all converged to the same solution. This sensitivity is sufficient to address the possibility that cell-specific monosomy X mosaicism may be one explanation for the longstanding enigma of a gender differential for autoimmune diseases [12].

Fig. 4.

B allele plots derived from SNP array data. (a) Mixing experiment showing B allele frequency plots of the normalized cumulative distribution function (CDF) of data points in the heterozygous region. The CDF is formed from the data values between 0.15 and 0.85 on the 0% monosomy data set and all the corresponding loci on the other plots. For the CDF plots, the modelled fitted data and experimental data are both superimposed on this scale. A series of iterated fits to the real data, with resulting residuals, is graphed next to each mixture. The minimum number of residuals converges on the experimental data’s true mosaic percent, within pipetting error. (b) B allele plots for 10 selected chromosomes from 10 separate individuals. [i] Monosomy/disomy X (58%, varies with cell type). [ii] Disomy/trisomy12 (15.6%). [iii] Mosaic Y monosomy (18.9%) in a male with pseudoautosomal region of X. [iv] Partial mosaicism for 20q13.32 to qter with distal region of homozygosity. The log R ratio excludes a deletion of the region of homozygosity at 20q13.33 [v] Partial disomy/monosomy for two separate regions of chromosome 5 (63%, varies with cell type). [vi] Mosaicism for 1pter to 1p35. [vii and viii] Two siblings with variable mosaicism for 3q. Approximate mosaicism for iv:1.1% cen-q21.1, 6.2% q21.2-q25, 10.3%q25.1-q26.31, 14.9%q26.31-q27.3 and 15.8% from q28 to qter). [ix] Variable mosaic 3p. [x] Variable mosaicism for chromosome 15q from 0% to 31.7% at qter.

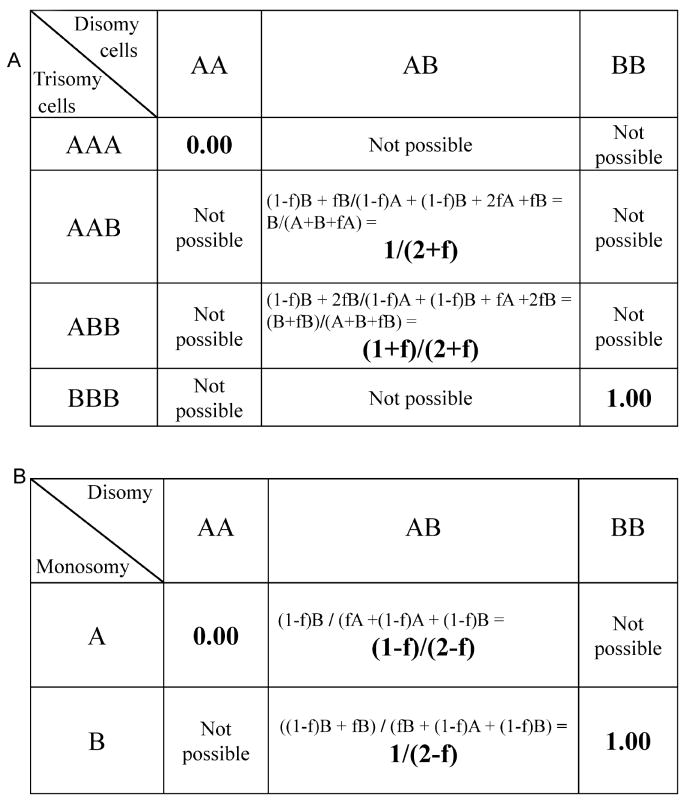

Fig. 3.

Punit square data for models of mosaicism.

a.) Graphical representation of the possible number of alleles in a single locus for a disomy/trisomy mosaicism. In this representation, A is the more frequent allele and B the less frequent allele at every polymorphic locus. All possible combinations of the disomy cell line and the derived trisomy cell line are shown. There are only four possible states for the trisomy cell line, and only four possible states can arise from the three states in the disomy cell line that gave rise to the trisomy line. The equations for the net B allele frequency are the fraction of each allele contributed by the trisomy line (f) times the specific allele (A, A and B for one and A, B, B for the other) plus the remaining fraction of the disomy line (1-f) times the specific allele for that line (A, B), divided by the total sum of all the alleles in both cell lines. If the B allele intensity is presumed to be equal between the A and B alleles, then these equations reduce to 1/(2+f) and (1+f)/(2+f), respectively.

b.) Graphical representation of the possible number of alleles in a single locus for a monosomy/disomy mosaic mixture. There are only four possible outcomes at any one locus for a fraction of the monosomy line of f. The allele equations for the B allele frequency are as described above and for equal intensities of the A and B alleles (the non homozygous possibilities) they reduce to the terms (1-f)/(2-f) and 1/(2-f), respectively. It is important to note that only one of these possibilities exists at each locus in the actual experimental data, but that all four possible states are present many times in the many loci that are sampled by a high density SNP array.

2.2 DANFIP identifies clinically relevant mosaicism in 10 different individuals

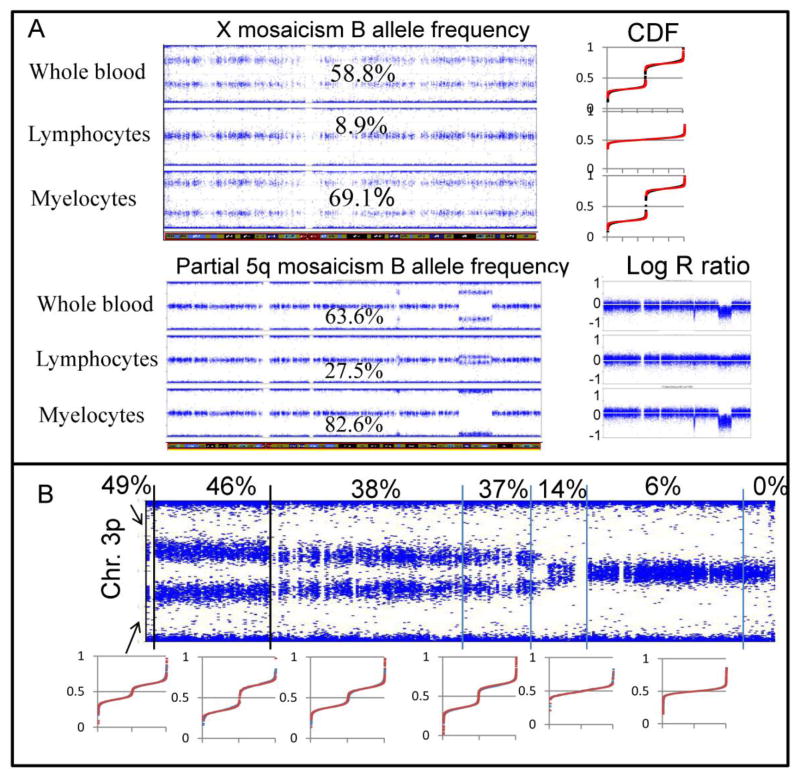

Of 10 examined individuals with mosaicism, 3 had whole chromosome mosaicism. These included (i) 57% monosomy X, (ii) 15.6% trisomy 12, and (iii) 18.9% monosomy Y (Fig. 4B i-iii). In case i, the clinical karyotype reported 12% monosomy X, which is the upper limit of normal for age. Our initial mosaic estimate for this case by CDF analysis was 56.9%, very discrepant with the commercial karyotype report. After review and interphase FISH of 200 cells from the cytogenetic culture, the estimated mosaicism was revised to only 18%. One possible reason for the discrepancy with the SNP analysis on uncultured whole blood DNA was an unequal level of mosaicism in the lymphocyte (cytogenetic) versus non-lymphocyte (SNP) cell types. To test this, a second independent sample was obtained and subjected to SNP-based CDF regression analysis as well as interphase FISH studying 200 nuclei using whole uncultured blood. Both studies substantiated the prior SNP-based CDF regression result. Furthermore, since the karyotype was performed on cultured T cells, we fractionated T cells and myeloid cells to determine the source of the mosaicism. SNP-based CDF regression and interphase FISH of the T cells showed 10.5% and 8.9% mosaicism, respectively (Fig. 5A). For the myeloid cells, the values were 56.5% and 69.1% mosaicism, respectively (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Examples of complex mosaicism detected by SNP/CDF analysis. (a) B allele plots of X monosomy/disomy mosaic after cell fractionation. The CDFs for each fraction are to the right of each B allele frequency plot; black CDF dots are actual data and red are the fitted regression. Also shown are the B allele plots of the partial 5p monosomy/disomy mosaicism after cell type fraction. The log R ratios for these samples are shown to the right of each plot, and the very minimal change in the T cell intensity is apparent. (b) Variable degree of monosomy/disomy for the distal portion of 3p. Subregions of the B allele plot were analyzed by CDF for percent mosaicism as shown in the corresponding CDF plots in the bottom half of the figure. Blue dots are actual CDF data; red dots show regression fit.

For case ii, who had a trisomy/disomy mosaicism of chromosome 12, there was no difference between the SNP-based CDF regression and cytogenetic cell counts, suggesting that T lymphocytes and myelocytes had the same degree of mosaicism in that blood sample. The preliminary cytogenetic report was actually normal 46,XY, but on inquiry, a single trisomy 12 cell was seen among the first 20 cells counted by Giemsa banding; after the SNP-based CDF regression results were made known, the mosaicism was confirmed on analysis of 200 nuclei by interphase FISH. For case (iii), the patient declined participation in confirmatory cytogenetic studies.

Seven individuals with hematologic diagnoses exhibited mosaicism for regions of different chromosomes ((iv)-(x) in Fig. 4B)). CDF analysis of the mosaic regions gave percentages of mosaicism with precisions of 1% or better. Subsequent fractionation of blood cells into myeloid and lymphocytic cells for one individual confirmed low mosaicism for a region on 5q in lymphocytes and high mosaicism for the same region in myeloid cells (Fig. 5A) (manuscript in preparation). Interestingly, four of the seven individuals ((vii), (viii), (ix), and (x) in Fig. 4B), who are described elsewhere [13], had bone marrow failure and graded mosaicism for loss of the distal portions of single ends of a single chromosome (3q, 3p or 15q). This previously undescribed mosaicism was characterized by greater monosomy in the distal telomeric region and progressively less monosomy centrally and was verified by qPCR [13]. Illustrating this, segmented analysis of one data set showed a decrease in monosomy from 49% to 0% over 50.3Mb (Fig. 5B). This strongly suggests that several different cell subpopulations are losing more and more of a single end of a single chromosome, until a subpopulation has too little chromatin for viability. The positions where monosomy begins (i.e., where disomy is no longer required for survival) may mark the location of dosage-sensitive viability genes. Cell lines with such variable degrees of mosaicism may be models for studying telomere maintenance. Additionally, this finding suggests that uniform telomere loss is not the sine qua non of bone marrow failure disorders [14, 15].

3. Discussion

We illustrate several advantages of CDF regression analysis [11] for quantifying mosaicism from SNP arrays. First, due to the hundreds-to-thousands of data points that occur in the heterozygous region of the B allele frequency plot even for segmental mosaicism, the DANFIP method detects mosaicism with a precision and accuracy of at least 0.1% and 4%, respectively. Second, the method surveys the entire genome at high resolution, whereas flow cytometry, qPCR and FISH probes are directed at specific regions. Third, this approach avoids cell culture artefacts. Fourth, it does not require live cells and is not dependent upon the mosaicism being present in T cells, because it can be performed on any tissue from which sufficient DNA can be extracted, including cells that cannot be sorted.

As for any technique, there are limitations to the DANFIP method. First, it requires at least one, and ideally several, normal diploid specimen(s) to serve as the reference sample. Second, the mosaic model must be known or inferred to fit the appropriate mosaic CDF. Finally, like any other technique analyzing the B allele frequency from SNP chip data, CDF analysis will be degenerate for complex mosaicism such as that seen in tumors; however, the degenerate models can inform follow-up studies in the proper regions. Nonetheless, most mosaicism encountered in undiagnosed heritable human diseases is simple deletion monosomy, partial monosomy, simple trisomy, partial trisomy, or uniparental disomy with trisomy mosaicism, and these are well suited to detection and characterization by the DANFIP technique.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrate that the DANFIP method of CDF analysis for high-density SNP array data quantifies mosaicism in a simple, rapid, and precise manner and adds to the proven uses of SNP arrays. In this context, SNP array data provide an excellent complement to exome and genome sequencing in the quest for disease-causing genomic aberrations.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1 DNA samples

Whole blood samples were obtained by peripheral venipuncture with informed consent under protocol 76-HG-0238 (“Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Other Genetic Disorders”), approved by the NHGRI institutional review board. Normal controls were obtained from unaffected relatives enrolled in the NIH UDP and consented to the same protocol. DNA was extracted from ten milliliters of whole blood using the Gentra Puregene Blood kit (Qiagen, Inc, Valencia, CA USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Anonymous samples from patients enrolled in two bone marrow failure protocols were provided by coauthors and processed in the same manner. DNA purity was determined by measuring absorbance at 280/260 (nanodrop, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE USA.). Pipetting samples was performed with adjustable standard laboratory micropippets with typical DNA concentrations of 70ng/ul and typical volumes of 5 to 20ul. The estimated accuracy and precision was ±5% for samples combined in the mixing experiment.

5.2 Blood cell subtype separations and DNA purification for SNP analysis

White blood cells were separated from whole blood using EasySep magnetic beads (STEMCELL Technologies Inc. Vancouver, BC, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Monocytes were separated using CD33+, CD66b+ antibody coupled magnetic beads (EasySep Kit#186783). Lymphocytes were isolated with CD3+ antibody coupled magnetic beads (EasySep Kit#18081). Isolated T cells and monocytes were split into aliquots for FISH and karyotyping and for DNA extraction, which was performed using the Puregene protocol (Qiagen Inc., Valencia CA, USA). To remove the magnetic beads attached to the cells at the start of the extraction, centrifugation was performed at 45,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C after the protein precipitation step instead of the suggested 2,000 × g for 10 min, and at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 20°C after the final DNA hydration. DNA concentrations less than 300 ng/ul worked best to allow sedimentation of all traces of magnetic beads. A repeat spin was performed under the same conditions when needed. DNA prepared by this method had the same call rate success when run on SNP chips as whole blood DNA prepared without any magnetic bead separations.

For one case with bone marrow failure case, myeloid cells were enriched by serially depleting the peripheral white blood cells of T and B cells using CD3+ and CD20+ antibody coated magnetic beads. The DNA isolations were performed as above.

5.3 Karyotype and FISH analyses

Quest Labs, Inc. (Chantilly VA), a CLIA approved company, performed the karyotyping and FISH analyses using standard, CLIA-approved procedures. A 72 hr phytohemagglutinin-stimulated culture was used to generate metaphase cells for Giemsa staining. FISH was performed on cultured cells, and upon our request, on unstimulated white blood cells. All blood cell fractions were processed in the same manner as the whole blood specimens. No attempt was made to remove the magnetic beads from these specimens, as they did not interfere with either the cytogenetic culture nor the FISH probe hybridization.

5.4 SNP chip hybridization

Illumina Omniquad and OmniExpress SNP chips (Illumina Inc. SanDiego CA) were run in the NHGRI core lab using purified whole blood or enriched-cell DNA without modification of the standard protocols. Results were processed in Genome Studio Softwarev2010.1. The call rates were over 99.5% in all samples. The data were normalized, meaning that the Illumina chip reader has scaled each intensity measurement so that the B allele frequency range is between 0.0 to 1.0, and forces the average value for all loci with even numbers of A and B allele intensities to be 0.5 accross the entire data set of samples in Genome Studio project. This occurs as part of the standard function of importing data by the Genome Studio software.

Regions of mosaicism are detected by observing the presence of a split in the middle band of the B allele frequency plot (Fig. 1C, D); this visual survey is rapid and straightforward. The model for analysis, either monosomy/disomy or trisomy/monosomy, is inferred by other means, such as a B allele split wider than 0.7 (only possible in monosomy/disomy), and inspection of the absolute intensity of the log R ratio. Log R ratio intensities can also differentiate mosaicism from duplication when the B allele frequency split of the middle two bands are near 0.33 and 0.67. Levels of mosaicism below 15% were primarily recognized by the fact that the middle, or “heterozygous” (AB) band of the B allele frequency plot was wider than other regions of the same sample and wider than the same region of other concurrently run samples. Mosaic mixtures as small as 4% alter the kurtosis value for a B allele frequency middle band and thus can be distinguished from a normal middle band even when visual widening of that band is not obvious; see the mother/son mixing experiment. The lower limits of detecting mosaicism are not the focus of this report and is left for future work.

In general, data points from the mosaic regions were filtered to select only B allele frequencies between 0.15 and 0.85. The absolute values of these limits differ, however, depending upon the experimentally observed separation of the distribution of the middle band(s) of the B allele plot from the homozygous (all A or all B) bands for any set of chips. Therefore, for the X chromosome mixing experiments and the X chromosome mosaic cell fractionation experiments, concurrently run chips producing the narrowest distribution of that middle band provided the set of SNP loci whose B allele frequencies were between 0.15 and 0.85. These same SNP loci were then used for the analysis of all other samples in the experiments.

5.5 Data analysis (DANFIP method)

The algorithm for analysis of mosaicism using the DANFIP method is outlined in Figure 2. The initial step was to extract the data from the heterozygous SNPs within the chromosomal segment to be analyzed for mosaicism (i.e., the AB region of a B-allele frequency plot). Any size region may be selected ranging from an entire chromosome to only a few hundred contiguous SNPs corresponding to approximately 1Mb at current SNP densities. For cases of varying levels of mosaicism, several regions may be selected. Each region is typically analyzed separately, but if two regions of the same chromosome appear to have the same level of mosaicism, they could be combined (for example see Fig. 5Bv).

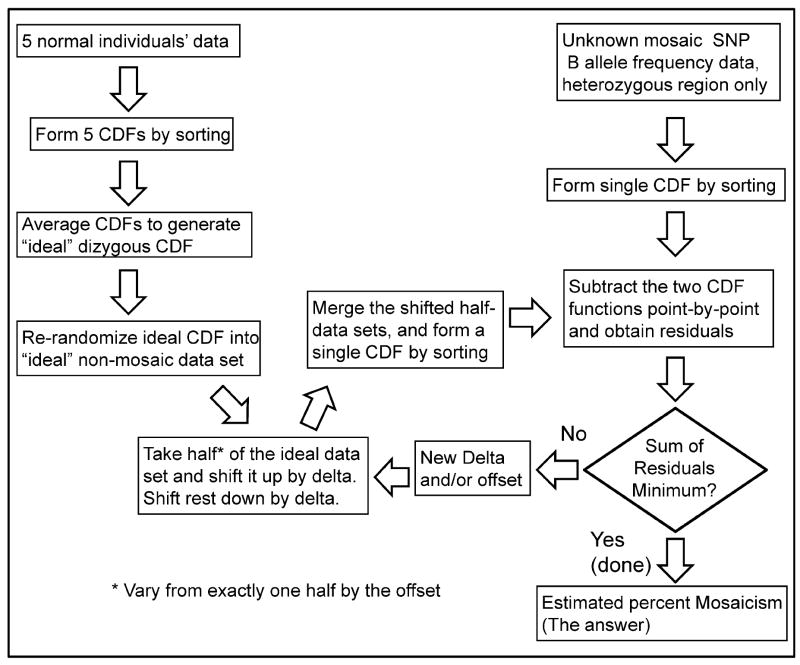

Fig. 2.

Block algorithm for implementing the DANFIP analysis for the nonhomozygous B allele frequency data from a series of 5 controls and an experimental region of mosaic data. CDF refers to a Continuous Distribution Function; delta is described in the Methods.

Next, an equivalent number of heterozygous control data points are selected from the region analogous to that for which the mosaicism data are being analyzed. These may come from other regions of the same sample not visually thought to be mosaic or, as we chose, the same region from other samples run concurrently and containing no evidence of mosaicism as determined by the samples with the narrowest B allele frequency distribuitions in the same regions as the mosaic sample to be quantified. The control data points are formed into their CDFs and all CDF data are normalized to a global average B allele frequency value of 0.5 (Fig. 1E, H). The control CDF values are averaged point by point to create a smoothed CDF. The next step involves modeling a mosaic data set by separating data into two equivalently distributed subsets and shifting upward half these points and shifting downward the other half, but the selection of which direction any point of the smoothed CDF will be shifted must be random. Therefore, the experimentally derived, smoothed control CDF is re-randomized prior to applying the shift to each point.

Next comes a series of iterative control data shifts, with half of the points shifted up and half down. The purpose is to iterate towards the magnitude of the shift that best fits the actual mosaic data determines the percent mosaicism. For the initial normal data shift, an arbitrary seed value can be used for the initial value for the fraction of mosaicism(f); the CDF is smooth and continuous and has no local minima. The type of mosaicism also determines the magnitude of the shift for a given fraction of mosaicism.(see Fig. 3A, B for examples of trisomy/disomy and monosomy/disomy models). The magnitude of the shift delta (δ) is half the distance defined by the splitting of the two middle bands of the B allele frequency for any specific model of mosaicism and for that fraction (f) of mosaicism. For example, delta is -0.5±(1/(2+f)) for a trisomy/monosomy mosaic B allele frequency plot.

Once the initial shift of half the data up and half down is accomplished, the shifted control data are combined and reformed into a new, working estimate of the experimental CDF that now represents a mosaicism of fraction f. The mosaic experimental data are also formed into a CDF (Fig. 1F, I, G, J) and paired to the working estimated CDF representing a mosaicism of fraction f. (See Fig. 1 and Supp. Video for a visualization of this process.) The absolute values of the point-by-point differences (residuals) between the working estimate mosaic CDF made from the shifted control data, and the experimental mosaic CDF made from the region that is being analyzed are summed to give the global magnitude of residuals between theoretical and actual CDFs. The sum of those residuals is a single parameter that measures how well the theoretical model fits the experimental data.

The initial guess of the fraction of mosaicism can be followed by repeated additional guesses, with comparison to the actual data and determination of residuals for each value “f” and each shift of delta. Using a nonlinear regression algorithm, these iterative functions will converge on a minimum sum of residuals; that is the best estimate of “f”, the true fraction of mosaicism. The analysis will proceed efficiently because the CDF functions are continuous and well behaved for all mosaic chromosome regions that contain more than a few dozen heterozygous SNPs. In our analyses, all regressions converged on the global minimum in less than 120 seconds using an unmodified standard commercial desktop computer running an unsophisticated nonlinear regression module (Excel Solver), even for whole chromosomes with tens to hundreds of thousands of data points. This was the same machine that runs the Illumina Genome studio software, obviating the need to change machines or operating systems when applying this method to data from Genome Studio. The manual for constructing an excel spreadsheet that implements this method is contained in the Supp. 2.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

It defines an efficient and rapid method of quantifying mosaicism detected by broadening or splitting of the middle (heterozygous) fluorescence intensity on a B allele frequency plot.

It justifies this approach to recombination mapping by showing its ability to detect artificial X-chromosome monosomy to within pipetting error.

It shows that this techniques was able to diagnose full and partial chromosome mosaicism missed by other techniques.

It identified a new disease mechanism of single graded telomere loss.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roxanne Fischer, Richard Hess, MaryPat Jones and Ursula Harper in the NHGRI Genomics Core for their excellent technical contributions. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute. Dr. Farrar was supported by NIH grant K08 HL092224. Dr. Lipton and Dr. Vlachos are supported by RO1 HL 079571.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nazarenko SA, Timoshevsky VA, Sukhanova NN. High frequency of tissue-specific mosaicism in Turner syndrome patients. Clin Genet. 1999;56:59–65. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lespinasse J, Gicquel C, Robert M, Le Bouc Y. Phenotypic and genotypic variability in monozygotic triplets with Turner syndrome. Clin Genet. 1998;54:56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velagaleti GV, Tapper JK, Rampy BA, Zhang S, Hawkins JC, Lockhart LH. A rapid and noninvasive method for detecting tissue-limited mosaicism: detection of i(12)(p10) in buccal smear from a child with Pallister-Killian syndrome. Genet Test. 2003;7:219–223. doi: 10.1089/109065703322537232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballif BC, Rorem EA, Sundin K, Lincicum M, Gaskin S, Coppinger J, Kashork CD, Shaffer LG, Bejjani BA. Detection of low-level mosaicism by array CGH in routine diagnostic specimens. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:2757–2767. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung SW, Shaw CA, Scott DA, Patel A, Sahoo T, Bacino CA, Pursley A, Li J, Erickson R, Gropman AL, Miller DT, Seashore MR, Summers AM, Stankiewicz P, Chinault AC, Lupski JR, Beaudet AL, Sutton VR. Microarray-based CGH detects chromosomal mosaicism not revealed by conventional cytogenetics. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1679–1686. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross J, Peters G, Wu Z, Brohede J, Hannan GN. Resolution of trisomic mosaicism in prenatal diagnosis: estimated performance of a 50K SNP microarray. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:1197–1204. doi: 10.1002/pd.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlin LK, Thiel BD, Bonnemann CG, Medne L, Ernst LM, Zackai EH, Deardorff MA, Krantz ID, Hakonarson H, Spinner NB. Mechanisms of mosaicism, chimerism and uniparental disomy identified by single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1263–1275. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conlin LK, Spinner NB. Cytogenetics into Cytogenomic: SNP Arrays Expand the Screening Capabilities of Genetics Laboratories. Illumina Corporation; San Diego: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jinawath N, Zambrano R, Wohler E, Palmquist MK, Hoover-Fong J, Hamosh A, Batista DA. Mosaic trisomy 13: understanding origin using SNP array. J Med Genet. 2011;48:323–326. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.083931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson TW, Darling DA. Asymptomatic theory of certain “goodness of fit” criteria based on stochastic processes. Am Math Stat. 1952;23:193–212. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wampler JE. Analysis of the probability distribution of small random samples by nonlinear fitting of integrated probabilities. Anal Biochem. 1990;186:209–218. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Invernizzi P, Pasini S, Selmi C, Gershwin ME, Podda M. Female predominance and X chromosome defects in autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrar JE, Vlachos A, Atsidaftos E, Carlson-Donohoe H, Markello TC, Arceci RJ, Ellis SR, Lipton JM, Bodine DM. Ribosomal protein gene deletions in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alter BP, Baerlocher GM, Savage SA, Chanock SJ, Weksler BB, Willner JP, Peters JA, Giri N, Lansdorp PM. Very short telomere length by flow fluorescence in situ hybridization identifies patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2007;110:1439–1447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calado RT. Telomeres and marrow failure. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:338–343. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.