Abstract

Objective

To determine whether resuscitation of infants who failed to develop effective breathing at birth increases survivors with neurodevelopmental impairment.

Study design

Infants unresponsive to stimulation who received bag and mask ventilation at birth in a resuscitation trial and infants who did not require any resuscitation were randomized to early neurodevelopmental intervention or control. Infants were evaluated by trained neurodevelopmental evaluators masked to both their resuscitation history and intervention group. The 12-month neurodevelopmental outcome data for both resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants randomized to the control groups are reported.

Results

The study provided no evidence of a difference between the resuscitated (N = 86) and the non-resuscitated infants (N = 115) in the percentage of infants at 12 months with a mental developmental index < 85 on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II (primary outcome) (18% versus 12%; p = 0.22) and in other neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Conclusions

The overwhelming majority of infants who received resuscitation with bag and mask ventilation at birth have 12-month neurodevelopmental outcomes in the normal range. Longer follow-up is needed because of increased risk for neurodevelopmental impairments.

Keywords: Resuscitation, intellectual disability, low and middle income countries, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, developmental outcome

Infants who require resuscitation at birth are at increased risk of neonatal mortality,1 cerebral palsy,2 and intellectual disabilities3. About six to 10% of all newly-born infants need some assistance to establish normal breathing at birth.4–6 Once spontaneous breathing is established, most of these infants survive without requiring further support during the post natal period.4

A multi-national controlled study (FIRST BREATH Trial) in which community birth attendants were trained in the World Health Organization (WHO) Essential Newborn Care course (which included bag and mask ventilation with room air) reduced stillbirths and perinatal mortality in deliveries performed by birth attendants.7 In a multi-center first level facility controlled study, implementation of the same educational program reduced 7-day (early) neonatal mortality.8

Because infants who survive following bag and mask ventilation are at higher risk for neurodevelopmental impairment, a subgroup of infants resuscitated during the FIRST BREATH Trial is being followed as part of a randomized controlled trial to determine if a home-based intervention program can improve neurodevelopmental outcome at 3 years. Before efforts to substantially scale up neonatal resuscitation are instituted, it is important to confirm that there will not be a marked increase in handicapped survivors. Thus, the investigators evaluated the 1-year data on the control groups (both resuscitated and not resuscitated) to assess the neurodevelopmental outcome without unblinding the trial. The current study was to explore the hypothesis that infants who received bag and mask resuscitation but did not have severe encephalopathy during the neonatal period would have comparable risk of low mental developmental index (MDI < 85) at 12 months to infants who did not require any resuscitation.

METHODS

Infants in three countries (India, Pakistan, and Zambia) in the FIRST BREATH Trial who had received bag and mask resuscitation were screened for the Brain Research to Ameliorate Impaired Neurodevelopment - Home-based Intervention Trial (BRAIN-HIT, clinicaltrials.gov ID# NCT00639184). The BRAIN-HIT is a randomized controlled trial aimed at ameliorating impaired neurodevelopment in survivors following bag and mask resuscitation using a home-based, early developmental intervention delivered by parents who were instructed and supervised by trained home visitors (parent trainers). Details on the trial design have been published.9 Birth asphyxia was defined as the inability to initiate or sustain normal breathing at birth using the WHO’s definition.10 This definition is very inclusive as in developing countries many neonates die due to primary or secondary apnea which is coded as birth asphyxia. Infants were ineligible if they weighed < 1500 grams at birth, their neurological examination at 7 days was severely abnormal (grade III by Ellis classification),11 or if the mother was < 15 years or unable/unwilling to participate. Infants with birth asphyxia unresponsive to stimulation and who had bag and mask ventilation at birth were randomly selected during the first week after birth using a computer generated list from infants enrolled in the FIRST BREATH Trial. These infants were matched for country and month of birth to infants without birth asphyxia or other perinatal complications. Consent was obtained after the 7-day neurological assessment. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International, and each participating clinical site.

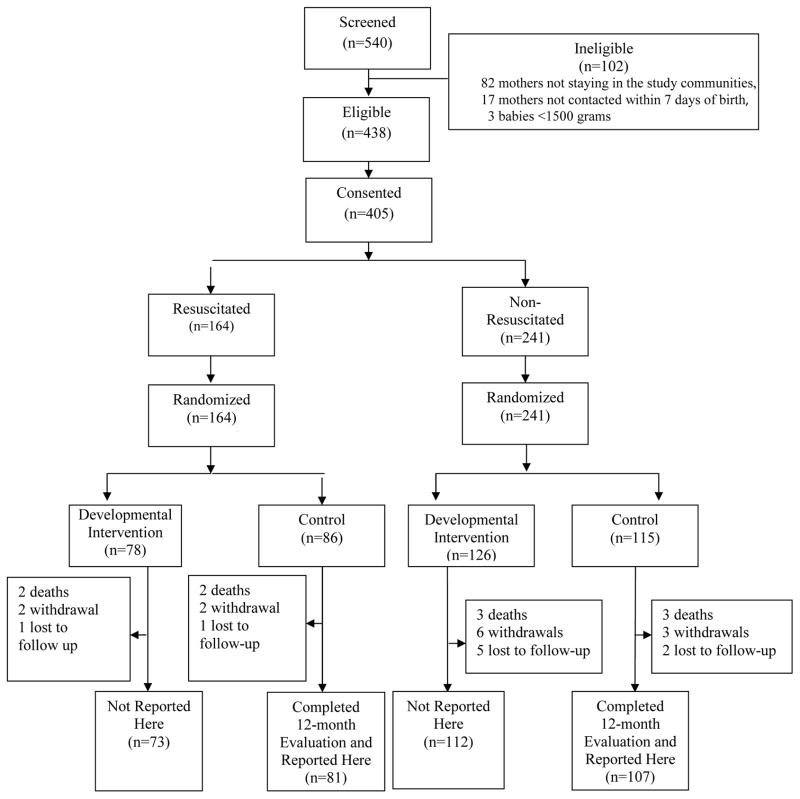

The two groups compared in this study were derived from a total of 540 infants screened from November 2006 to November 2008 (Figure). 188 of the 201 enrolled control infants who completed the 12-month evaluations are the subjects of this 1-year follow-up study. The infants randomized to the developmental intervention are not reported as the investigators are masked to their outcome until the three year follow-up is completed.

Figure 1.

Screening and randomization flow chart. Only control infants are reported in this study.

All neurodevelopmental assessment instruments were administered by certified study neurodevelopmental evaluators (pediatricians and psychologists who were familiar with the local language and culture) who were masked to the birth history and intervention group. Each evaluator was trained in an intensive 4-day training that covered purpose and correct administration of each item.

The Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II (BSID-II) underwent extensive pre-testing at each site to verify validity and a few items were slightly modified to make the BSID-II more culturally appropriate (e.g., image of a sandal instead of a shoe). The BSID-II was administered directly to each child in the appropriate language using standard material.12 The Ages and Stages Questionnaire, 2nd ed. (ASQ)13, which is a screening tool, was used to assess parent-reported child development in the domains of communication, gross motor and fine motor, problem solving, and personal-social development using age-specific forms. The ASQ provided a secondary measure of general child development observed in the home environment. To remove issues of literacy, the ASQ was administered in an interview format with the parent regarding the child’s behavior. This questionnaire has been previously used in low- and middle-income countries.14,15 Data on health measures collected included weight, height, head circumference, and hearing and vision impairment.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was the percentage of children with moderate to severe cognitive development as assessed by a BSID-II Mental Development Index (MDI) < 85. Secondary outcomes included a BSID-II MDI < 70, BSID-II Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) measures, the ASQ measures, and general health status measures. Severe impairment was defined as MDI < 70, PDI < 70, hearing impairment, and/or visual impairment. Moderate/severe impairment also included MDI < 85 and PDI < 85. Below normal ASQ domain scores indicating the need for further testing were determined using standardized cut points (2 standard deviations below the sample population mean). Weight, height, and head circumference percentiles were determined using the WHO growth curves16 Vision screening was assessed with tracking of an object 180°. Hearing screening was assessed with consistent responses to verbal commands and environmental sounds.

Data management

Maternal and neonatal data were collected by trained birth attendants who were supervised by community coordinators. Visit data were collected by parent trainers. Developmental outcome data were collected by the neurodevelopmental evaluators. The data were transmitted electronically to the Data Coordinating Center (RTI). Data edits and inter- and intra-form consistency checks were performed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for monitoring enrollment and retention, completion of home visits, and completion of the 12-month evaluation. Point and interval estimates of relative risk were calculated using standard large-sample formulae to determine differences in maternal and neonatal characteristics and outcomes between the two groups.

RESULTS

Of the infants randomized to the control groups (N = 201), 86 infants enrolled received bag and mask ventilation (Resuscitated) and 115 infants enrolled did not require any resuscitation (Non-Resuscitated) (Figure). Maternal and infant characteristics appeared to be comparable between the groups except that resuscitated babies had lower Apgar scores and poorer 7-day neurological exam scores (Table I). Adherence to the home visits to one year was 99% to 100% for both the resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants, excluding the 6% who dropped out of the study.

Table 1.

Maternal and Infant Characteristics by Resuscitation Status

| Maternal characteristics | Resuscitated | Non-resuscitated |

|---|---|---|

| Completed 12-month evaluation - N | 86 | 115 |

| Age (years) - mean (SD) | 24 ± 5 | 26 ± 6 |

| Formal schooling completed - n/N (%) | ||

| None, illiterate | 37/84 (44) | 53/108 (49) |

| None, literate/primary | 27/84 (32) | 35/108 (32) |

| Some secondary/university | 20/84 (24) | 20/108 (19) |

| Married - n/N (%) | 81/86 (94) | 108/115 (94) |

| Parity - mean (SD) | 2.7 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 2.3 |

| Primiparous - n/N (%) | 31/84 (37) | 30/114 (26) |

| Vaginal vertex delivery - n/N (%) | 82/84 (98) | 109/109 (100) |

| Prenatal care - n/N (%) | 70/86 (81) | 101/115 (88) |

| Infant characteristics | ||

| Gender (male) - n/N (%) | 51/86 (59) | 63/115 (55) |

| Birth weight (grams) - n/N (%) | ||

| 1500–2499 | 16/83 (19) | 24/107 (22) |

| 2500–2999 | 40/83 (48) | 48/107 (45) |

| ≥ 3000 | 27/83 (33) | 35/107 (33) |

| Gestational age (week) - mean (SD) | 37.3 ± 2.3 | 37.5 ± 1.9 |

| Gestational age categorized - n/N (%) | ||

| 28–36 | 31/86 (36) | 36/113 (32) |

| 37–41 | 52/86 (60) | 72/113 (64) |

| ≥ 42 | 3/86 (4) | 5/113 (4) |

| Apgar scores–median (25%ile–75%ile) | ||

| 1 minute | 5 (4 – 5) | 9 (9 – 10) |

| 5 minute | 9 (7 – 10) | 10 (9 – 10) |

| Resuscitated - n/N (%) | ||

| Type of resuscitation (all that apply) | ||

| Bag and mask | 83/84 (99) | 0/115 (0) |

| Chest compressions | 2/84 (2) | 0/115 (0) |

| Other | 1/84 (1) | 0/115 (0) |

| Neurological exam score - n/N (%) | ||

| Normal | 73/83 (88) | 110/110 (100) |

| Grade 1 (Mild) | 10/83 (12) | 0/110 (0) |

| Grade 2 (Moderate) | 0/83 (0) | 0/110 (0) |

| Location of birth - n/N (%) | ||

| Home | 37/84 (44) | 59/111 (53) |

| Clinic | 17/84 (20) | 25/111 (23) |

| Private/public/government hospital | 29/84 (35) | 27/111 (24) |

| Other | 1/84 (1) | 0/111 (0) |

| Birth attendant - n/N (%) | ||

| Physician | 9/84 (11) | 9/111 (8) |

| Nurse/midwife/health worker | 41/84 (49) | 48/111 (43) |

| Traditional Birth Attendant | 34/84 (40) | 49/111 (44) |

| Family/Unattended | 0/84 (0) | 5/111 (5) |

The primary outcome measure, MDI < 85, occurred in 18% of resuscitated and in 12% of non-resuscitated infants (Table II), but the location and width of the 95% confidence interval for the relative risk (0.77, 3.02) precluded a definitive decision about whether the groups differed clinically. Low PDI scores were more prevalent than low MDI scores (overall 27% of the infants had PDI < 85) but the point estimates of the relative risks for the PDI scores (Table II) suggested that differences between the resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants were relatively small. The rates of moderate and severe impairment did not differ between the resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants. ASQ fine motor scores indicating the need for further testing appeared higher among the resuscitated infants when compared with the non-resuscitated infants (17% versus 7%) but all other ASQ measures appeared comparable between groups.

Table 2.

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II Scores, Other Major Neurodevelopmental Outcomes by Resuscitation Status, and Ages and Stages Questionnaires Score

| Resuscitated (n=81) | Not Resuscitated (n=107) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDI <85 – n/N (%) | 15/81 (18) | 13/107 (12) | 1.52 (0.77, 3.02) |

| MDI <70 – n/N (%) | 5/81 (6) | 1/107 (1) | 6.60 (0.79, 55.44) |

| MDI – mean ± SD | 96 ± 16 | 98 ± 13 | -- |

| PDI <85 – n/N (%) | 24/81 (30) | 27/107 (25) | 1.17 (0.74, 1.87) |

| PDI <70 – n/N (%) | 11/81 (14) | 11/107 (10) | 1.32 (0.60, 2.89) |

| PDI – mean ± SD | 96 ± 22 | 95 ± 20 | -- |

| Hearing impairment – n/N (%) | 1/81 (1) | 0/107 (0) | -- |

| Visual impairment – n/N (%) | 1/81 (1) | 0/107 (0) | -- |

| Moderate/severe impairment – n/N (%) | 28/81 (35) | 34/107 (32) | 1.09 (0.72, 1.64) |

| Severe impairment – n/N (%) | 18/81 (16) | 11/107 (10) | 1.56 (0.74, 3.30) |

| ASQ – Total score | |||

| mean ± SD | 234 ± 66 | 247 ± 47 | -- |

| median (25%ile – 75%ile) | 263 (195–280) | 260 (220–280) | -- |

| Domain score indicating referral needed – n/N (%) | |||

| Communication (≤ 15.8) | 2/58 (3) | 0/90 (0) | -- |

| Gross motor (≤ 18.0) | 9/58 (16) | 9/90 (10) | 1.55 (0.65, 3.68) |

| Fine motor (≤ 28.4) | 10/58 (17) | 6/90 (7) | 2.59 (0.99, 6.73) |

| Problem solving (≤ 25.2) | 6/58 (10) | 7/90 (8) | 1.33 (0.47, 3.76) |

| Personal – social (≤ 20.1) | 7/58 (12) | 6/90 (7) | 1.81 (0.64, 5.12) |

(BSID-II) Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd Edition; (MDI) Mental Development Index; (PDI) Psychomotor Development Index; (ASQ) Ages and Stages Questionnaire

At 12 months of age, the resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants had comparable weight, height, and head circumference. However, rates of percentiles <5 were very common for weight (43 and 36%), height (51 and 53%) and head circumference (33 and 29%) for resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that infants born in rural communities in developing countries who survived following bag and mask resuscitation had an 82% chance of having normal mental development (MDI > 85%) and an 84% chance of being free of severe disability at 1 year. These results are comparable with those of the infants who did not require resuscitation at birth. Other neurodevelopmental and health outcomes also were comparable in resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants.

Study infants were part of a large multi-country study in which training of birth attendants in neonatal resuscitation and other essential newborn care knowledge and skills reduced stillbirths and perinatal mortality.7 Training of midwives with the same educational program reduced neonatal and perinatal mortality in a large multicenter study in a developing country.8 Thus, it appears that training birth attendants can reduce perinatal mortality and that the majority of the additional survivors are likely to have a normal outcome through 1 year after birth.

A limitation of this study is that infants with severe encephalopathy diagnosed at 1 week were excluded from this study. These infants were excluded because infants with severe neonatal encephalopathy are at high risk of death. In addition, because the main trial9 was designed to assess three year outcomes, there was a concern that those infants would not survive or would not benefit from the neurodevelopmental interventions in the randomized controlled trial. However, only three infants were excluded because of a severely abnormal neurological examination consistent with severe encephalopathy of the 540 infants screened. Another limitation is that infants were evaluated at 1 year when neurodevelopmental indications are less predictive of long term outcomes than later evaluations. Although outcomes may improve from infancy to school age17,18, studies have found that individual stability of scores was only moderate to high, despite comparable prevalence of disability at 6 and 11 years, in former preterm infants.19 It is possible that more survivors will have problems that manifest during childhood and adulthood.20–22 Although this is the largest study of its kind in developing countries, trends for increased risk for adverse outcomes in the resuscitated infants may be of clinical significance though the study did not have the power to draw firm conclusions about these differences. Larger studies and longer follow-up to school age is needed. The high prevalence of infants with anthropometric measures below the 5th percentile is due in part to the reference group of the WHO study, which was purposely designed to produce standards among healthy children living under conditions likely to favor the achievement of their full genetic growth potential.16 These curves, which includes subjects from Southeast Asia and Africa, were developed for worldwide use.

There are limited data on follow-up in infants from developing countries who were resuscitated at birth. In a study in China, infants with Apgar scores ≤ 6 at 5 minutes had only a 3% rate of cognitive impairment.23 These infants may be comparable with those in our study, although the inclusion criterion in our study was based on receipt of resuscitation rather than Apgar scores. However, mortality and morbidity markedly increase with more severe encephalopathy during the neonatal period, even for births in referral hospitals. In a study of newborn infants with severe encephalopathy in Nepal, mortality was 97%.24 In addition, 74% of the survivors who had moderate encephalopathy during the neonatal period and 26% of the survivors who had mild encephalopathy had abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes at 1 year. Almost 50% of the babies included in the current study were born at home. It is likely that survivors with severe encephalopathy following birth asphyxia born at home births died early during the first week of life. Therefore, because the study enrolled infants with mild to moderately abnormal neurologic exams at one week, it is likely that the infants with milder degrees of encephalopathy are over represented, which may be another reason for the low incidence of mortality and impairment in our study. The current study suggests that death or severe disability occurs in less than 10% of the infants born in communities in developing countries who survived following bag and mask resuscitation at birth. Because of the potential trends we observed and the risk for later manifestations of developmental impairment, further research is needed to assess the impact of neonatal encephalopathy on performance at school age, or even later in childhood, in the developing world and to assess the impact of early developmental stimulation programs.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants HD43464, HD42372, HD40607, and HD40636) and the Fogarty International Center (grant TW006703), and the Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Abbreviations

- MDI

Mental Development Index

- BSID-II

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II

- DALY

disability adjusted life years

- WHO

World Health Organization

- BRAIN-HIT

Brain Research to Ameliorate Impaired Neurodevelopment - Home-based Intervention Trial

- RTI

Research Triangle Institute

- ASQ

Ages and Stages Questionnaire, 2nd ed

- PDI

Psychomotor Development Index

- SD

Standard Deviation

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Trial registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00639184.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halloran DR, McClure E, Chakraborty H, Chomba E, Wright LL, Carlo WA. Birth asphyxia survivors in a developing country. J Perinatol. 2009;29:243–249. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Macki N, Miller SP, Hall N, Shevell M. The spectrum of abnormal neurologic outcomes subsequent to term intrapartum asphyxia. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlman JM, Risser R. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the delivery room. Associated clinical events. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:20–25. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170130022005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal N, McMillan DD, Yee WH, Akierman AR, Yee YJ. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the standardized neonatal resusitation program. J Perinatol. 2001;21:388–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deorari AK, Paul VK, Singh M, Vidyasagar D. Impact of education and training on neonatal resuscitation practices in 14 teaching hospitals in India. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2001;21:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, Chomba E, Tshefu A, Garces A, et al. Newborn-care training and perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:614–623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlo WA, McClure EM, Chomba E, Chakraborty H, Hartwell T, Harris H, et al. Newborn care training for midwives and neonatal and perinatal mortality rates in a developing country. Pediatrics. 2010 Nov;126:e1064–1071. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallander JL, McClure E, Biasini F, Goudar SS, Pasha O, Chomba E, et al. Brain research to ameliorate impaired neurodevelopment--home-based intervention trial (BRAIN-HIT) BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basic Newborn Resuscitation: A Practical Guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis M, Manandhar DS, Manandhar N, Wyatt J, Bolam AJ, Costello AM. Stillbirths and neonatal encephalopathy in Kathmandu, Nepal: an estimate of the contribution of birth asphyxia to perinatal mortality in a low-income urban population. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14:39–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development: Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squires J, Potter L, Bricker D. The ASQ’s user’s guide for the Ages and Stages Questionnaires: A parent-completed, child monitoring system. Baltimore, MD: Brooks; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heo KH, Squires J, Yovanoff P. Cross-cultural adaptation of a pre-chool screening instrument: comparison of Korean and US populations. J Intell Disab Re. 2008;52:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai HLA, McClelland MM, Pratt C, Squires J. Adaptation of the 36-month ages and stages questionnaire in Taiwan: results from a preliminary study. J Early Interv. 2006;28:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. [Accessed: October 14, 2011.];The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/mgrs/en/

- 17.Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, Samara M EPICure Study Group. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Wilson-Costello D, et al. Poor predictive validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for cognitive function of extremely low birth weight children at school age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:333–341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson S, Fawke J, Hennessy E, Rowell V, Thomas S, Wolke D, et al. Neurodevelopmental disability through 11 years of age in children born before 26 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e249–e257. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odd DE, Lewis G, Whitelaw A, Gunnell D. Resuscitation at birth and cognition at 8 years of age: a cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moster D, Lie RT, Irgens LM, Bjerkedal T, Markestad T. The association of Apgar score with subsequent death and cerebral palsy: A population-based study in term infants. J Pediatr. 2001;138:798–803. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.114694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorngren-Jerneck K, Herbst A. Low 5-minute Apgar score: a population-based register study of 1 million term births. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao X, Sun S, Yu R, Sun J. Early intervention improves intellectual development in asphyxiated newborn infants. Intervention of Asphyxiated Newborn Infants Cooperative Research Group. Chin Med J (Engl) 1997;110:875–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis M, Manandhar N, Shrestha PS, Shrestha L, Manandhar DS, Costello AM. Outcome at 1 year of neonatal encephalopathy in Kathmandu, Nepal. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:689–695. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]