Abstract

Endotoxin tolerance (ET) triggered by prior exposure to Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands provides a mechanism to dampen inflammatory cytokines. Receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140) interacts with NF-κB to regulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes. We identify lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of Syk-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation on RIP140 and RelA interaction with RIP140. These events increase recruitment of SOCS1-Rbx1 (SCF) E3 ligase to tyrosine-phosphorylated RIP140, thereby degrading RIP140 to inactivate inflammatory cytokine genes. Macrophages expressing a non-degradable RIP140 were resistant to the establishment of ET for specific genes. The results reveal RelA as an adaptor for SCF ubiquitin ligase to fine-tune NF-κB target genes by targeting co-activator RIP140, and an unexpected role for RIP140 protein degradation in resolving inflammation and ET.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), are responsible for sensing microbial infection, tissue damage, and initiation of innate immune responses. Upon exposure to TLR ligands in immune cells, TLRs trigger inflammatory signaling to activate NF-κB and MAPK pathways and promote proinflammatory cytokine production such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β)1, 2. These proinflammatory cytokines not only induce inflammation but also modulate the adaptive immune response. Recently, chronic inflammation and aberrant production of proinflammatory cytokines have been demonstrated to play critical roles in many diseases, especially metabolic diseases such as Type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and atherosclerosis 3–5. Therefore, tight control of proinflammatory cytokine production and resolution of inflammation after infection and/or tissue damage are important for maintaining tissue homeostasis. Diminished proinflammatory signaling, non-permissive histone modifications, chromatin remodeling and microRNA production induced by inflammatory stimuli have all been shown to resolve inflammation by impairing proinflammatory cytokine production via inhibiting NF-κB and MAP kinase (MAPK) activities 2, 6–9.

Endotoxin tolerance (ET) provides a protective mechanism to reduce over production of proinflammatory cytokines in response to infection. Defects in the establishment of ET lead to a higher incidence of septic shock and mortality in individuals with infection. However, individuals with ET become immunocompromised 10, 11. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms controlling ET is important to the design of interventions to fine tune immune responses. Besides monocytes, macrophages are the major cell type involved in ET in animals, and LPS, a TLR4 ligand, is most commonly used to induce ET in vivo and in vitro 9, 12. Although suppression of TLR-mediated inflammatory signaling pathways by negative regulators has been proposed as a mechanism for the establishment of ET, this mechanism cannot fully explain why and how certain genes are efficiently silenced whereas some other genes using the same signaling pathways can still be activated in tolerated macrophages 8. A growing number of studies have demonstrated that changes on chromatin, including loss of RelA binding, histone modification and chromatin remodeling, provide the major regulatory mechanisms for the suppression of specific genes in ET 8, 9, 12, 13. But how these changes on specific chromatin targets are controlled is largely unclear.

Receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140) can act as co-repressor or a co-activator for various transcriptional factors and nuclear receptors, and it is mainly expressed in metabolic organs and tissues, including adipose tissue, liver, and muscle 14–16. RIP140-null mice resist diet-induced T2DM, and RIP140 regulates lipid and glucose metabolism in metabolic tissues through its nuclear and cytoplasmic functions 15, 17–21. Proteomic analyses have identified various post-translational modifications of RIP140 that modulate its function and sub-cellular distribution, such as serine and threonine phosphorylation, lysine acetylation, sumoylation, and lysine and arginine methylation 22–25. But tyrosine phosphorylation has not been detected on RIP140 in earlier studies. Recently, RIP140 was found to function in macrophages as a co-activator for NF-κB by recruiting CREB-binding protein (CBP) to modulate TLR-induced (at least TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4) production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-1β, and IL-626. Additionally, modulation of RIP140 expression by microRNA-33 affected inflammatory potential of macrophages in response to intracellular cholesterol levels 27. These studies reveal a role for RIP140 in proinflammatory cytokine production, and suggest that it is important to regulate RIP140 expression to modulate inflammatory potential in macrophages.

Ubiquitin contains five lysine residues (K6, K11, K29, K48, and K63) that are involved in monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination. Specifically, K48-linked ubiquitination targets proteins to proteasome-mediated degradation 28. Ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated protein degradation are involved in both positive and negative regulation of TLR signal transduction. To this end, IκB degradation is best characterized, which controls NF-κB activity by regulating subcellular localization of NF-kB 1, 2. Additionally, SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine-signaling-1)-Rbx1 (ring-box protein 1) is known to interact with RelA and promote RelA degradation in nuclei 29, 30. But it is largely unknown how regulation on specific chromatin targets to negatively regulate the inflammatory response is achieved.

We report here that RIP140 degradation, triggered by exposure of macrophages to TLR ligands, as a novel mechanism for negatively regulating specific genomic targets in the inflammatory response to promote ET. LPS stimulates the interaction of RIP140 with RelA, which leads to the recruitment of SOCS1-Rbx1 (SCF) E3 ligase. In addition, LPS activates Syk-mediated phosphorylation of RIP140 on Tyr364, Tyr418 and Tyr436, facilitating its ubiquitination. Together these trigger efficient RIP140 protein degradation to dampen inflammation and induce ET. Prevention of RIP140 degradation by pre-treatment of macrophages with IFNγ or over-expression of a non-degradable RIP140 effectively diminished LPS-induced ET in vitro and in vivo. These results not only uncover a novel regulatory mechanism of inflammatory response by RIP140, but also show that RelA acts as an adaptor for E3 ligase to dynamically control its specific co-activator to fine-tune its own transcriptional activity for specific chromatin targets.

Results

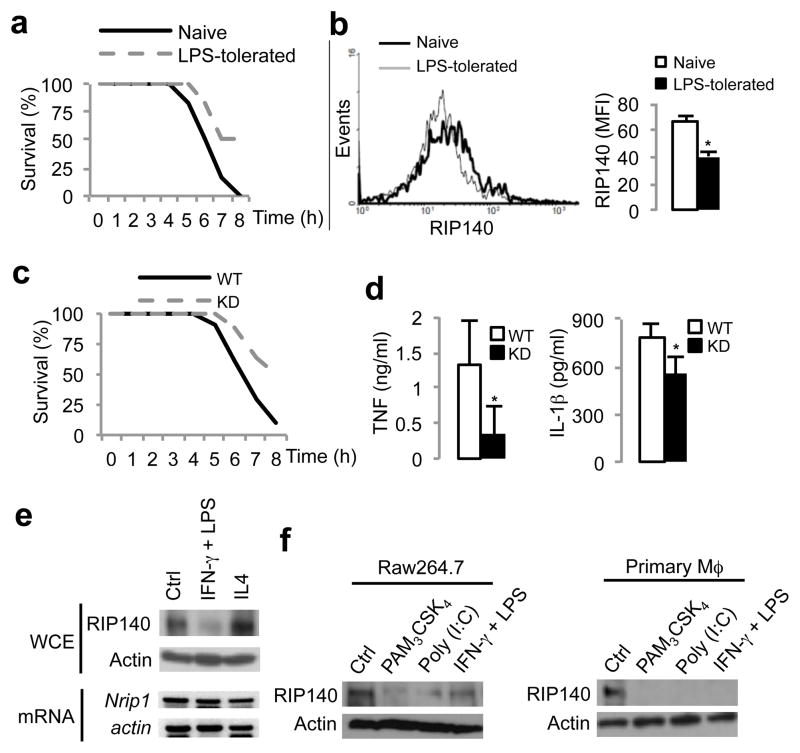

TLR ligands decrease RIP140 protein in macrophages

To determine whether RIP140 expression can be modulated by LPS exposure in the establishment of ET, we pre-injected mice with saline (control vehicle) or a low dose of LPS, challenged animals with a lethal dose of LPS and D-galatosamine 16 h later, and then monitored the animals’ survival (Supplementary Fig. 1). As predicted, exposure to a low dose of LPS prior to the lethal dose of LPS substantially increased the survival 31 (Fig. 1a). We monitored the intensity of RIP140 in F4/80+-peritoneal macrophages, and found RIP140 protein in LPS-tolerated mice decreased ~ 40% as compared to the saline group (Fig. 1b). We reasoned that since RIP140 modulates proinflammatory cytokine production by acting as an NF-κB co-activator 26, 27, down-regulation of RIP140 in macrophages may dampen inflammatory responses and improve the survival in acute sepsis. To test this theory we made a transgenic mouse model with macrophage-specific silencing of RIP140, because RIP140 whole body knockout mice exhibited altered lipid and glucose metabolism which made the use of this mouse line in a septic shock model intractable. The human CD68 promoter was used for macrophage-specific expression of RIP140-specific siRNA32 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Macrophages from these transgenic knock-down mice (KD) expressed lower mRNA levels of RIP140 (by ~20%) (Supplementary Fig. 2b). As predicted, RIP140 KD mice had a higher survival (Fig. 1c) and lower circulating TNF and IL-1β as compared to the wild type (WT) mice (Fig. 1d). These results show that down-regulation of RIP140 in macrophages can be protective against septic shock.

Figure 1.

Exposure to TLR ligands reduces RIP140 in macrophage in vitro and in vivo. (a) Survival of mice, monitored every hour after challenging with a lethal dose of LPS with D-galactosamine. (n=10 per group). Exposure to a low dose of LPS prior to the lethal dose of LPS substantially increased the survival. (b) Left: histogram of RIP140 expression in F4/80 positive population from isolated peritoneal macrophages. Right: Mean fluorescence intensity of RIP140. Results are presented in mean ± SD., n=3; *: P < 0.05. (c) Survival of wild type mice (Wt) and macrophage-specific RIP140 knockdown mice (KD), monitored every hour after challenging with a lethal dose of LPS with D-galactosamine. (n=8 per group). (d) Serum TNFα and IL-1β from WT and KD mice after stimulation of LPS for 2 h. Results are presented in mean ± SD., n=4; *: P < 0.05 as compared to wild type group. (e) Immunoblot and semi-quantitative PCR analyses of RIP140 protein and mRNA levels in primary peritoneal macrophages after stimulating with the vehicle (Ctrl), M1 stimulus (LPS plus IFN-γ) or M2 stimulus (IL-4) for 24 h. (f) Expression of RIP140 in Raw264.7 and primary peritoneal macrophages after treatments -vehicle (Ctrl), Pam3CSK4, poly (I:C) or LPS with IFN-γ, for 24 h.

Macrophage polarization, including classical (M1) and alternative (M2) activation plays a critical role in various diseases 33, 34. Since LPS is a stimulus for M1 activation, we asked whether RIP140 was differentially affected in M1 versus M2 activation in macrophages. In agreement with the in vivo data, M1 stimulus (IFNγ+LPS), but not M2 stimulus (IL4), reduced RIP140 protein in both primary (Fig. 1e) and Raw264.7 (RAW) macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 3) without significantly affecting RIP140 mRNA levels. Furthermore, LPS exposure decreased RIP140 protein in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 4). To differentiate various TLRs and adaptors’ signaling pathways, we examined the effects of Pam3CSK4 (TLR2 ligand) and poly (I:C) (TLR3 ligand) on RIP140 protein. Stimuli for TLR2, TLR3 or TLR4 could all reduce RIP140 (Fig. 1f). Altogether, these results reveal that RIP140 protein is down-regulated in macrophages after exposure to ligands for TLR2, TLR3 or TLR4, and suggest that reduction of RIP140 may provide a regulatory mechanism to reduce inflammatory response and the establishment of ET.

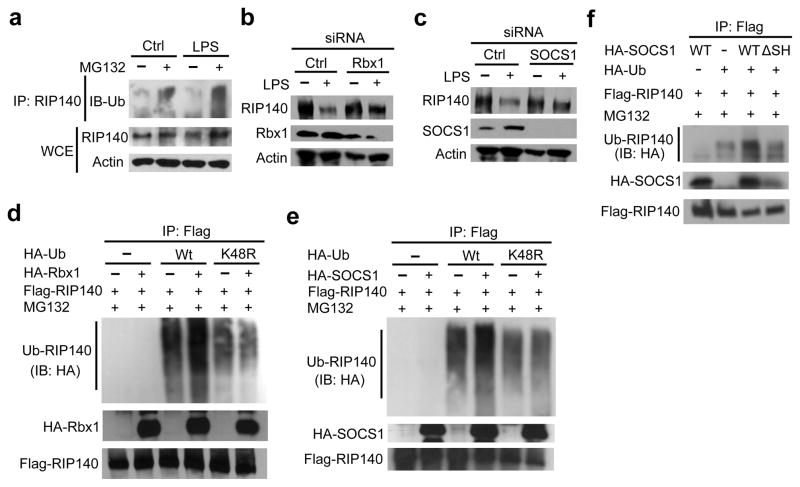

LPS triggers RIP140 degradation by SCF E3 ligase complex

To determine whether protein degradation contributes to LPS-triggered reduction in RIP140 protein, we treated RAW cells with LPS in the absence or presence of proteasome inhibitor, MG132. MG132 effectively increased ubiquitination on RIP140 under LPS treatment (Fig. 2a), suggesting that proteasome-mediated degradation of ubiquitinated RIP140 contributes to LPS-triggered reduction in RIP140 protein in tolerated macrophages. LPS also promoted RIP140 degradation when examined using a pulse-chase experiment (Supplementary Fig. 5). In a bacterial two-hybrid screening, we identified ring-box protein 1 (Rbx1) as an RIP140-interacting protein (data not shown). Because Rbx1 is a component of SCF (Skp, culin, F-box-containing) E3 ligase complex that transfers the polyubiquitin chain to lysine residues of target proteins 29, we then examined whether Rbx1 contributes to LPS-triggered ubiquitination of RIP140. Indeed knocking down Rbx1 blocked LPS-induced degradation of RIP140 in both primary macrophages (Fig. 2b) and RAW cells (Supplementary Fig. 6a). SOCS1, another component of SCF E3 ligase, can associate with Rbx1 and is responsible for target recognition, and SOCS1 also negatively regulates inflammation and contributes to the establishment of ET 35–37. We therefore examined whether SOCS1 was involved in LPS-triggered degradation of RIP140. As expected LPS induced the expression of SOCS1 protein; and silencing SOCS1 also reduced LPS-triggered RIP140 degradation in primary macrophages (Fig. 2c) and RAW cells (Supplementary Fig. 6b). To determine if RIP140 could be a direct target of SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase, we performed in vivo ubiquitination assay in 293T cells by ectopically co-expressing Flag-tagged RIP140 and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Rbx1 or SOCS1, in the presence of the wild type, or its mutant form, of ubiquitin. Indeed, both SOCS1 and Rbx1 promoted RIP140 ubiquitination in the presence of the wild type ubiquitin, but not the lysine-to-arginine (K48) mutated ubiquitin (Fig 2d and 2e). These experiments also confirm that RIP140 can associate with Rbx1 and SOCS1. Because SOCS1 recognizes tyrosine-phosphorylated substrates through its SH2 domain 29, 30, 37, we then determined whether SOCS1’s SH2 domain was required for RIP140 degradation by using an SH2-mutated SOCS1 (SOCS1-ΔSH) that failed to recognize its specific targets. Unlike the wild type SOCS1 that effectively stimulated RIP140 ubiquitination, SOCS1-ΔSH failed to do so (Fig. 2f). These results demonstrate that LPS triggers RIP140 degradation by promoting SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase-mediated ubiquitination of RIP140.

Figure 2.

LPS promotes RIP140 degradation through SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase-mediated K48 polyubiquitination. (a) Immunoblot analysis of RIP140 and polyubiquitinated RIP140 in Raw264.7 macrophages stimulated for 6 h with indicated treatments. (b) Immunoblot analysis of RIP140, Rbx1 and actin in primary peritoneal macrophages stimulated for 24 h with a control treatment or LPS after transfection with control or Rbx1 siRNAs. (c) Immunoblot analysis of RIP140, SOCS1 and actin in primary peritoneal macrophages stimulated for 24 h with a control treatment or LPS after trasfection with control or SOCS1 siRNAs. (d, e, f) In vitro ubiqtuination analysis of RIP140 in 293T cells. 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids as indicated and treated with 10 μM MG132 for 6 h before lysis. (d) Cell lysates were immunopreciptated with anti-Flag-agarose beads and immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Flag to detect Flag-RIP140 or anti-HA to detect polyubiquitinated RIP140 and HA-Rbx1. (e) Cell lysates were immunopreciptated with anti-Flag-agarose beads and immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Flag to detect Flag-RIP140 or anti-HA to detect polyubiquitinated RIP140 and HA-SOCS1. (f) 293T cells were transfected with Flag-tagged RIP140 and HA-tagged Ub in conjunction with HA-tagged SOCS1 wild type (Wt) or HA-tagged SOCS1-ΔSH (ΔSH). Cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 for 6 h before lysis. Cell lysates were immunopreciptated with anti-Flag-agarose beads and immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Flag to detect Flag-RIP140 or anti-HA to detect polyubiquitinated RIP140 and HA-SOCS1. All immunoblots were performed at least twice.

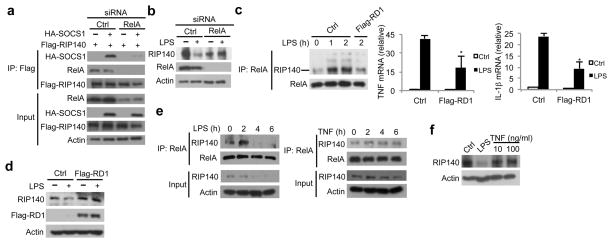

RelA is an adaptor for SOCS1 to associate with RIP140

Although we demonstrated that SOCS1-Rbx1 can associate with RIP140 in vivo, we failed to detect direct interaction of RIP140 with SOCS1 in vitro (data not shown). Since RelA has been shown as a target for nuclear SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase and RIP140 interacts with RelA to coactivate its transcriptional activity 26, 29, 30, we then asked whether RIP140 associates with SOCS1 in a RelA-dependent manner in co-immunoprecipitation assays. We found that, in 293T cells with ectopic expression of Flag-tagged RIP140 with or without HA-tagged SOCS1, RIP140 failed to associate with SOCS1 in RelA-silenced cells (Fig. 3a). Further, RIP140 could no longer be degraded in RelA-silenced primary macrophages (Fig. 3b) or RAW cells (Supplementary Fig. 6c), under LPS stimulation. These results suggest that the association of RIP140 with RelA provides a regulatory step for recruiting SOCS1 to RIP140. Because RelA interacts with the amino-terminus of RIP14026, we tested whether over-expressing a Flag-tagged amino-terminus of RIP140 (Flag-RD1) could reduce the association of RIP140 with RelA and LPS-triggered RIP140 degradation. Indeed, over-expressing Flag-RD1 reduced LPS-triggered association of RIP140 with RelA in RAW cells, down-regulated target genes’ expression (such as TNF and IL-1β) (Fig. 3c), and dampened LPS-triggered RIP140 degradation (Fig. 3d). Taken together, our results show that RelA acts as an adaptor for SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase to control RIP140’s degradation.

Figure 3.

RelA acts as adaptor for SCF ubiquitin ligase complex to trigger RIP140 degradation. (a) RelA is required for the interaction of RIP140 with SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase complex, determined by immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses. (b) Immunoblot analysis of RIP140, RelA and actin in primary peritoneal macrophages stimulated for 24 h with a control treatment or LPS after trasfection with control or RelA siRNA. (c) Over-expression of Flag-tagged RIP140 amino terminus (RD1) reduced the interaction of RIP140 with RelA. Raw264.7 macrophages were transfected with control plasmid (Ctrl) or Flag-tagged RD1 (RD1) and then stimulated with LPS for various durations. Cell lysates were collected and the interaction of RIP140 with RelA was determined by immunoprecipitation of RelA and then probed with RIP140. Right: the effect of RD1 on the basal and LPS-stimulated expression of TNF and IL-1β was determined by quantitative PCR. Results are presented in mean ± SD., n=3; *: P < 0.05 as compared to control treatment. (d) Raw264.7 macrophages were transfected with the indicated plasmid and then stimulated with, or without, LPS for 2 h. The expressions of RIP140 and indicated proteins were determined by immunoblot analysis. (e) Raw264.7 macrophages were treated with 10 μg/ml LPS (left panel) or 10 ng/ml TNF (right panel) for various durations and the interaction of RelA with RIP140 was determined by immunoprecipitation and immunblot. (f) The expression of RIP140 in primary peritoneal macrophages after 24 h treatments as indicated was determined by immunoblot analysis. All immunoblots were performed at least twice.

In addition to ligands for TLRs, TNF can also activate signaling cascade to promote NF-κB mediated proinflammatory cytokine production 3, 12, but it promotes ET through distinct mechanisms from that of LPS-induced ET 12. TNF failed to enhance RIP140-RelA complex formation above the basal level (Fig. 3e); and more importantly, after 24 h treatment, TNF still failed to decrease RIP140 protein in both primary macrophages (Fig. 3f) and RAW cells (Supplementary Fig. 7). These results further support our hypothesis that LPS-stimulated interaction of RIP140 with RelA results in the recruitment of SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase in a TLR-specific manner, which is required for RIP140’s degradation.

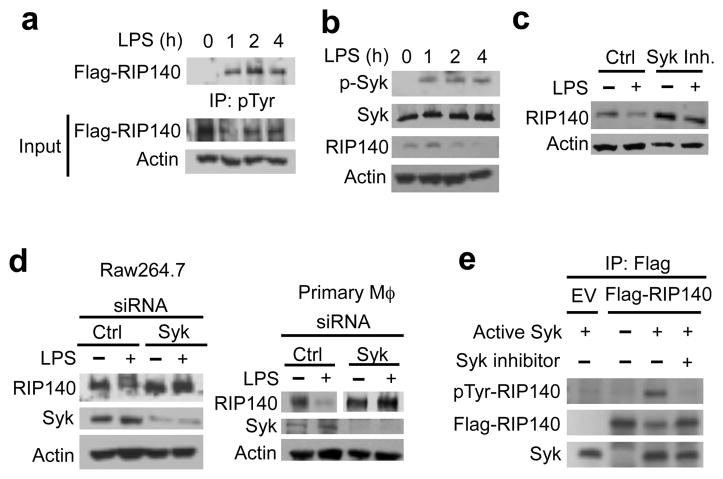

RIP140 degradation requires its phosphorylation

Tyrosine phosphorylation has a critical role in regulating proteasome-mediated protein degradation via various mechanisms 7, 28. Analysis of LPS-induced tyrosine phosphorylation on RIP140 revealed that RIP140 was phosphorylated within 1 h after LPS challenge, immediately before RIP140 degradation could be detected (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Syk, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, showed a similar activation kinetic after LPS challenge (Fig. 4b). Syk also plays an important role in resolving inflammation, and Syk-null mice are susceptible to LPS-induced sepsis 38, 39. We found that treating LPS-exposed RAW cells with the Syk inhibitor helped to sustain their RIP140 protein (Fig. 4c), and knocking down Syk prevented LPS-triggered RIP140 degradation in both primary macrophages and RAW cells (Fig. 4d). Additionally, we found that Syk was accumulated in the nuclei under LPS treatment (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Using a proximal ligation assay, we detected increased interaction of RIP140 with Syk in the nuclei of LPS-challenged RAW macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These results suggest that Syk may phosphoryate RIP140 to regulate its stability.

Figure 4.

Syk activity is required for LPS-induced RIP140 degradation. (a) Raw264.7 macrophages were transfected with Flag-tagged wild type RIP140 and then treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) in the presence of MG132 for indicated duration. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody-conjugated agarose. Phospho-RIP140 was determined by immunoblot of anti-flag. 10% input of cell lysate was used for immunblot. (b) Raw264.7 macrophages were treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for indicated duration. Whole cell lysates were collected and indicated proteins were examined by immunoblot. (c) Raw264.7 cells were pre-treated with a control vehicle or Syk inhibitor (Syk In.: Bay 61-3606) for 30 min and then cells were treated with LPS for 24 h. Cell lysates were collected and indicated proteins were determined by immunoblot analysis. (d) Immunoblot analysis of RIP140 expression in Raw264.7 macrophages and primary peritoneal macrophages transfected with control or Syk siRNAs after LPS treatment for 24 h. (e) Syk directly phosphorylates RIP140 in an in vitro kinase assay as described in method.

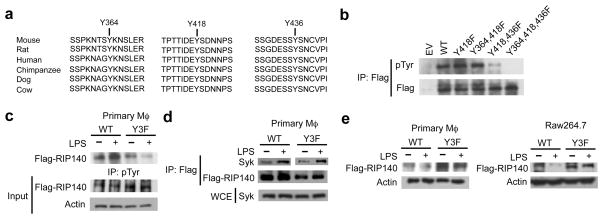

An in vitro kinase assay showed that Syk phosphorylated RIP140 on its tyrosine residues, and was blocked by the Syk inhibitor (Fig. 4e). Using group-based prediction system (GPS), we identified three highly conserved tyrosine residues on RIP140, which were predicted as Syk target sites (Fig. 5a). Using the same in vitro kinase assay, we demonstrated that mutations on all three tyrosine residues (Y3F: Y364F, Y418F and Y436F) effectively blocked Syk-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation on RIP140 (Fig. 5b). RIP140 with mutations on these three tyrosine residues (Y3F) exhibited drastically reduced tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 9) and became resistant to degradation in macrophages following LPS challenge (Fig. 5e). Both wild type and Y3F mutated RIP140’s still interacted with Syk in primary macrophages following LPS challenge (Fig. 5d). Although the Y3F mutated RIP140 exhibited a greater stability, it was possible that these mutations abolished the interaction of RIP140 with RelA, thereby reducing the association of RIP140 with SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase. It appeared that the Y3F mutant could still interact with RelA under the basal condition, and this interaction was also enhanced by LPS treatment (Supplementary Fig. 10). Further, this Y3F mutant remained associated with SOCS1 (Supplementary Fig. 11a). In vitro phosphorylated wild type Flag-RIP140 failed to associate with SOCS1 in a direct protein interaction assay (Supplementary Fig. 11b). These data support our conclusion that RelA acts as an adaptor to facilitate the association of RIP140 with SOCS1, and validate that Syk-mediated phosphorylation at three conserved tyrosine residues of RIP140 is critical for the conjugation of polyubiquitin chain on RIP140. But this is not required for SOCS1 to recognize RIP140 or the interaction of RIP140 with RelA.

Figure 5.

LPS-induced RIP140 degradation depends on Syk-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation on RIP140. (a) Schematic diagrams show the conserved amino acid sequences of RIP140 around the Syk target sites. (b) In vitro kinase assays of tyrosine phosphorylation on RIP140 with indicated mutations. (c) LPS-triggered tyrosine phosphorylation of WT RIP140 or tyrosine mutant RIP140 (Y3F) in vivo. Primary peritoneal macrophages were transfected with Wt RIP140 or tyrosine mutant RIP140 (Y3F) and then treated with or without LPS for 1 h. (d) The interaction of Flag-RIP140 with Syk in primary peritoneal macrophages challenged with LPS for 1 h. (e) Protein stability of WT RIP140 or tyrosine mutant RIP140 (Y3F) was determined by immunoblot analysis. Cells were treated with or without LPS for 24 h. All immunoblots were performed at least twice.

Attenuation of ET by preventing RIP140 degradation

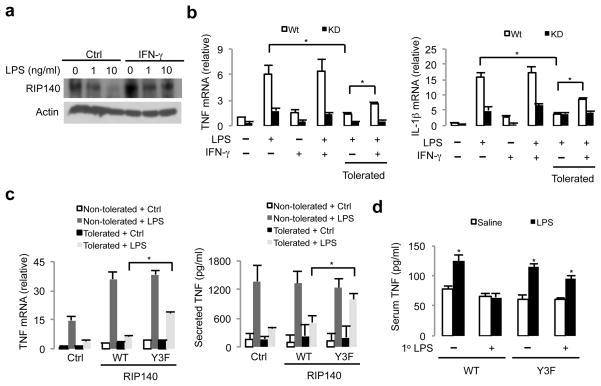

Exposure to LPS induced RIP140 degradation and reduced production of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages, suggesting that RIP140 degradation may resolve inflammation and promote the establishment of ET. IFN-γ activates macrophages to amplify the inflammatory response, and one of its important functions is to reduce ET and restore pro-inflammatory cytokine production 9, 40. Pre-treatment of macrophage with IFN-γ has been shown to overcome LPS-induced ET 9. Therefore we asked whether pre-treatment with IFN-γ could block RIP140 degradation, and if RIP140 was required for IFN-γ-restored inflammatory cytokine production, especially TNF and IL-1β, in tolerated macrophages. Indeed, pre-treatment with IFN-γ effectively suppressed LPS-triggered RIP140 degradation in primary (Fig. 6a) and RAW (Supplementary Fig. 12) macrophages, and IFNγ failed to restore TNF and IL-1β production when RIP140 was silenced (Supplementary Fig. 13). We also confirmed the requirement for RIP140 in IFN-γ’s effect to prevent ET, in experiments using primary peritoneal macrophages from wild type or macrophage-specific RIP140-silenced (KD) mice (Supplementary Fig. 14). IFN-γ effectively prevented ET in macrophages from the WT but not RIP140-silenced mice (Fig. 6b). To further investigate the role of RIP140 degradation in the establishment of ET, we introduced a control (Ctrl), wild type RIP140 (WT) or Y3F mutated RIP140 (Y3F) into RAW cells, induced their tolerance with LPS and then monitored production of proinflammatory cytokines under the second LPS stimulation. The Y3F mutant, but not the control or wild type RIP140, were resistant to tolerance induction with LPS, based on criteria like mRNA expression and protein production of TNF after the second LPS challenge (Fig. 6c). The effect on IL-1β mRNA expression was in agreement with this notion (Supplementary Fig. 15). Since altered signaling cascades in LPS-stimulated IKK and MAPK activations are also important characteristics of ET, we thus investigated whether the Y3F mutant prevented ET by augmenting these signaling pathways. This proved to be not the case because we did not observe any significant changes in these signaling cascades in RAW cells transfected with the wild type (WT) or Y3F mutant of RIP140, as compared to the control vector (Supplementary Fig. 16). These results show that expressing the non-degradable RIP140 (Y3F) attenuates ET, which occurs in a MAPK and IKK signaling-independent manner.

Figure 6.

Degradation of RIP140 is involved in the establishment of ET. (a) Pre-treatment of IFN-γ in primary peritoneal macrophages prevents LPS-facilitated degradation of RIP140. Cells were pre-treated with or without IFN-γ for 16 h and then challenged with LPS for another 6 h. (b) The mRNA levels of TNF (upper panel) and IL-1β (lower panel) from primary peritoneal macrophages treated according to the experimental design. (c) Raw264.7 macrophages were transfected with the control vector (Ctrl), Flag-tagged WT RIP140 or tyrosine mutant RIP140 (Y3F). Cells were treated with or without LPS for 16 h to become non-tolerated or tolerated states, respective. After 24 h, cells were then challenged with LPS. Upper: mRNA levels of TNF were determined by quantitative PCR. Lower: the levels of secreted TNF from culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. (d) Serum TNF production from macrophage reconstituted mice after stimulation of LPS for 1 h. Results are presented in mean ± SD., n=4; *: P < 0.05 as compared to saline group.

To further validate the effect of expressing the non-degradable RIP140 (Y3F) on ET in vivo, we introduced the wild type (WT) or Y3F mutant (Y3F) RIP140 into primary macrophages by lentiviral infection, and challenged them with LPS for 24 h. These macrophages were collected and injected into macrophage-depleted mice to achieve macrophage reconstitution (Supplementary Fig. 17). After macrophage reconstitution, mice were then challenged with LPS for 1 h and serum TNF was determined by ELISA. As expected, mice reconstituted with WT RIP140 macrophages failed to promote TNF production. However, mice reconstituted with Y3F mutant RIP140 macrophages still produced a higher amounts of serum TNFα in response to the second LPS challenge (Fig. 6d). Overall, our results demonstrate that RIP140 degradation is essential for the establishment of ET, at least based upon the criteria of TNF and IL-1β production. Moreover, prevention of RIP140 degradation, such as by pre-treatment with IFN-γ, can attenuate ET.

Non-degradable RIP140 reduces tolerance of specific genes

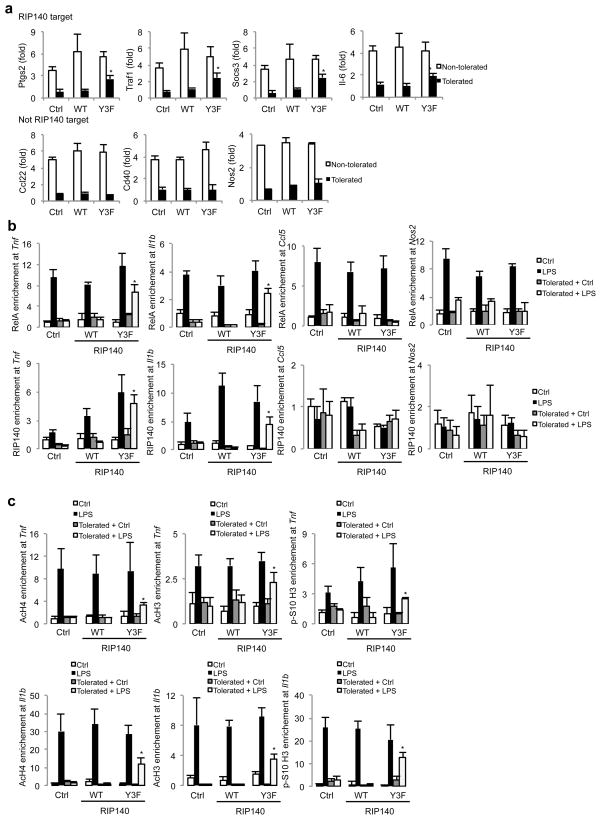

Genes expression from either LPS-tolerated or non-tolerated macrophages demonstrates TLR-induced histone modifications and chromatin remodeling in a gene-specific manner 8, 41. Microarray analysis has shown that most differentially expressed genes in RIP140-null macrophages were proinflammatory genes 26. We therefore compared the genes differentially expressed in RIP140-null macrophages to the tolerated and non-tolerated genes categorized in previous publications 8, 26, and found that nine of the tolerated genes but only one of the non-tolerated gene were RIP140 target genes (Supplementary Fig. 18). We examined whether over-expression of the non-degradable RIP140 (Y3F) in macrophages prevented ET for RIP140’s target genes. Ectopic expression of the Y3F mutant, but not the control vector or wild type RIP140, reduced tolerization of RIP140’s target genes (including Ptgs2, Traf1, Socs3 and Il6, in addition to Tnfα and Il1b). However, the Y3F mutated RIP140 failed to reduce tolerization of genes that are not the targets of RIP140, such as Ccl22, cd40 and Nos2 in both primary macrophages (Fig. 7a) and RAW cells (Supplementary Fig. 19). These results clearly show that RIP140 degradation contributes to the establishment of ET in a gene-specific manner.

Figure 7.

Prevention of RIP140 degradation retains RelA binding and increases active histone modification on tolerated genes’ promoters. (a) Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA of indicated genes in non-tolerated or tolerated primary peritoneal macrophages transfected with the control vector (Ctrl), wild type RIP140 (WT) or non-degradable RIP140 (Y3F). Cells were induced into non-tolerated or tolerated status and then re-challenged with 10 ng/ml LPS for another 2 h or 6 h. Relative folds of mRNA levels after the second stimulation with LPS were determined. Results are presented in mean ± SD., n=3; *: P < 0.05 as compared to the non-tolerated+LPS group. (b,c) Raw264.7 macrophages transfected with the control vector (Ctrl), wild type RIP140 (WT) or non-degradable RIP140 (Y3F) were induced into non-tolerated or tolerated status. Cells were then re-challenged with 10 ng/ml LPS for another 2 h. Chromatin IP (ChIP) was performed for indicated antibodies. (b) Relative occupancy of RelA (p65) (upper panel) and RIP140 (lower panel) on Tnf, Il1b, Ccl22 and Nos2 promoters were determined by real-time PCR analyses. (c) Relative occupancy of acetylated histone H4 (AcH4), acetylated histone H3 (AcH3) and phosphor-S10 histone H3 (p-S10 H3) on Tnf and Il1b promoters were determined by real-time PCR analyses. Results are presented in mean ± SD., n=3; *: P < 0.05 as compared to the control treatment of tolerated macrophages.

Most tolerated genes, such as TNF and IL-1β, are characterized by their non-permissive histone modifications and lower NF-κB binding on their promoters under LPS challenge8, 9, 12, 13, 41, 42. However, the underlying mechanism for these changes was unclear. Thus, we asked whether degradation of RIP140 is involved in changing these specific chromatin targets, by expressing the control vector, wild type RIP140 or Y3F mutant in RAW cells and inducing tolerance with LPS challenge. After stimulation with the second dose of LPS in macrophages, RelA and RIP140 binding on TNF, IL-1β, Ccl5 and Nos2 promoters were monitored by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). In response to LPS treatment, RIP140 binding on its targets (TNF and IL-1β) was enhanced, which did not happen on the non-RIP140 targets (Ccl5 and Nos2). RelA binding on promoters of TNF and IL-1β was also increased in the Y3F-transfected macrophages but not the other groups (Fig. 7b). We also monitored active histone modification, including acetylated histone H4 (AcH4), acetylated histone H3 (AcH3) and phosphor-S10 histone H3 (p-S10 H3) on RelA binding regions of TNF and IL-1β promoters. In addition to phosphor-S10 on histone H3, H3 and H4 acetylation was also increased in the Y3F-transfected macrophages, but not in the other groups in the tolerated state (Fig. 7c). Taken together, these results support the view that LPS-stimulated degradation of RIP140 contributes to the loss of RelA binding and active histone modifications on the promoters of pro inflammatory cytokine genes in tolerated macrophages.

Discussion

RIP140 promotes proinflammatory cytokine production by serving as a co-activator for NF-κB in macrophages exposed to TLR ligands. In this study, we show that exposure to TLR ligands triggers RIP140 degradation, leading to resolution of the inflammatory response and contributing to ET in a gene-specific manner. Syk-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation and RelA-dependent SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase recruitment are two prerequisites for LPS-triggered RIP140 degradation (Supplementary Fig. 20). To our knowledge, this unexpected finding is the first example of negative regulation of a TLR-mediated inflammatory response through targeting a specific NF-κB co-activator. This study also reveals that NF-kB, specifically the RelA subunit, can modulate its own transcriptional activity by recruiting the SCF (Skp, culin, F-box-containing) E3 ligase complex to target its associated co-activator.

Most studies of negative regulation of inflammation focus on TLR-mediated signal transduction and suggest that these regulations are involved in the establishment of ET 10, 11, 41. However, alterations on chromatin, including histone modifications and chromatin remodeling, have been shown to be able to render complete and gene-specific tolerance with a reduced signaling cascade 2, 41, 42. Although several potential negative regulatory mechanisms in the nucleus have been proposed, the link between these mechanisms and the specific changes on chromatin targets under ET induction was unclear. Among these nuclear regulatory events, it has been shown that the SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase, an SCF E3 ligase, can degrade RelA to terminate NF-κB’s transcriptional activity 29, 30, 43 and SOCS1 recognizes its substrate via its SH2 domain which interacts with phospho-tyrosine residues on substrate protein 37. We found Syk phosphorylates RIP140 on three tyrosine residues but failed to detect direct interaction of RIP140 with SOCS1, even for the RIP140 that had been phosphorylated by Syk. We did confirm that SH2 domain of SOCS1 to be essential for ubiquitination of RIP140. Since RelA association with SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase requires the SOCS1 SH2 domain 29, 43, and RelA directly interacts with RIP140, we conclude that RelA acts as an adaptor for SOCS1-Rbx1 E3 ligase to recruit RIP140 into the E3 complex. Consistent with this notion, SOCS1 knockout mice have a higher inflammatory response and reduced survival under septic shock, and SOCS1-deficient macrophages exhibit less ET 35, 36, which also supports our findings that SOCS1-mediated degradation of RIP140 resolves inflammation and promotes the establishment of ET. This study also reveals a previously unrecognized mechanism exerted by RelA itself to down-regulate its co-activator. This is the first case of regulation of a co-activator’s stability by an SCF E3 ligase via interaction with RelA.

Syk-null mice also have reduced survival and more severe inflammatory responses under LPS challenge, which suggests that Syk is involved in resolution of inflammation 38. A recent study reported that CD11b reduced TLR-triggered inflammatory response via Syk-mediated phosphorylation of MyD88 and TRIF 39. Our results presented here further support the role of Syk in negative regulation of inflammatory response in macrophages. Syk interacts with RIP140 in the nuclei and then phosphorylates RIP140 on three conserved tyrosine residues. The Y3F mutant RIP140 resists LPS-stimulated protein degradation, which may be due to inefficient ubiquitination on RIP140, because phosphorylation of these three tyrosine residues appears to be independent of RelA binding to RIP140 and the association of RIP140 with SOCS1. To this end, recent reports have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of a target protein can promote ubiquitination without affecting E3 ligase binding 44, 45. On the basis of results presented here, we propose that phosphorylation of the three tyrosine residues may change RIP140’s conformation and lead to exposure of specific lysine residues to E3 ligase. It remains to be determined which lysine residues on RIP140 are directly involved in ubiquitin conjugation and subsequent degradation.

This study demonstrates that RIP140 degradation contributes to ET in a gene-specific manner, which suggests that NF-κB interacts with RIP140 to activate only specific genes. Syk-mediated phosphorylation of RIP140 was ruled out as a regulator of the interaction of RIP140 with RelA. Because RelA possesses various post-translational modifications, depending on the stimuli 46, we postulate that specific modifications of RelA may regulate its interaction with RIP140, and may further determine its specific target genes. Therefore, it would be of interest to investigate the regulation of RelA-RIP140 interaction in the future. RIP140 acts, mainly, as a co-repressor for most transcription factors and nuclear receptors by recruiting HDAC and CtBP 47, 48, but it functions as a co-activator for NF-κB by recruiting CBP 26. It is possible that RIP140 may be modified by RelA-associated kinases or other enzyme machineries after interaction with RelA, which then leads to preferential recruitment of CBP. Recent studies have suggested that acetylation of histone H3 and H4 is important for NF-κB binding on chromatin 46. It would be important to investigate if the non-degradable RIP140 can facilitate RelA binding in the tolerated state by enhancing the acetyaltion status of histones around the RelA-binding region and how RIP140 may modulate chromatin configuration on these proinflammatory cytokine genes. Future analyses are needed to further elucidate the differences in these RIP140 protein complexes; these differences may be part of a novel mechanism for modulating RIP140’s biological activities.

It is generally believed that in metabolic tissues, RIP140 antagonizes the action of PGC-114. A previous study showed that a high-fat diet (HFD) increases RIP140 expression in macrophages, which enhances their proinflammatory potential 27. PGC-1β can promote M2 activation of macrophages 32 and RIP140 is important for proinflammatory cytokine production characteristic of M1 activation. It is very interesting that in this current study we find that degradation of RIP140 is essential to the establishment of ET, and that failure to degrade RIP140 attenuates ET induction in vitro and in vivo. It would be important to evaluate whether the stability of RIP140, or its protein, is related to individuals’ sensitivity to septic shock in clinical conditions.

Methods

Cell culture, transfection and mice

Raw264.7 macrophage cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in DMEM medium with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) were used for plasmid transfection. siRNAs were purchased from Qiagen and transfected by Hiperfect (Qiagen). All male C56BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson labtorary and maintained in the animal facility of Univerisity of Minnesota and were used at 6–12 weeks of age. Animal studies were performed with approval of University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Peritoneal macrophages were elicited by 4% thioglycolate and isolated as previous report 27. For the derivation of transgenic mice that overexpress shRNA to target RIP140 in macrophage lineage, the shRNA for RIP140 was mimicked as endogenous microRNA following reported method 49. The expression of this shRNA was driven by hCD68 promoter 32 and the expression DNA fragment was cloned into pWhere vector. Transgenic DNA fragment was excised by PacI and then injected into C57BL/6 mouse oocytes (Mouse genetics laboratory, University of Minnesota). Transgenic founder mice were genotyped by PCR using following primer set: Forward: 5′-GAGTTCTCAGACGCTGGAAAGCC-3′ and Reverse” 5′-GTCCAATTATGTCACACCACAGAAG-3′.F1–F4 progeny were used for this study.

Reagents

LPS and IFNγ were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Invitrogen, respectively. Recombinant mouse IL-4 was purchased from eBioscience. TNFα was from Cell Signaling. Mouse TNFα ELISA kit and mouse IL-1β ELISA kit were from BD Biosciences and Ray Biotech, respectively. siRNAs and Hiperfect were from Qiagene. Antibodies for actin, HA-tag, RelA (p65) and Syk were from Santa Cruz. Anti-RIP140 antibody was purchased from Abcam. Anti-SOCS1, anti-Rbx1 and anti-K48 conjugated ubiquitin antibodies were from Millipore. Protein G agarose-conjugated with anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody was ordered from Cell signaling. Anti-Syk antibody purchased from BioLegend and anti-RIP140 antibody were used for proximal ligation assay. MG132 was from Sigma-Aldrich and genistein was ordered from EMD chemicals.

Flow cytometry analysis

Mice were injected with 3ml 4% thioglycolate intraperitoneally. After two days, mice were injected intraperitoneally with low dose of LPS to achieve endotoxin tolerance (0.1 μg/25 g body weight) 27. After 24 h, mice were sacrificed and primary peritoneal macrophages were isolated and plated in DMEM with 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA for 1 h and then adherent cells were collected for flow cytometry analysis of RIP140 and F4/80. Flow cytometry analysis was performed as previous report 27.

In vivo ubiquitination assay

For in vivo ubiqtuination assay, 2 μg Flag-RIP140 and 0.2 μg HA-ubiquitin plasmids were transfected into 293T cell with or with 1 μg HA-SOCS1 or HA-Rbx1. After 24 h, the media were changed to normal culture medium with 5 μg/ml MG132 for another 6 h. Cells were collected and lysed with RIPA buffer. Immunoprecipitated complexes were subjected into SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-HA antibody.

Immunofluorescence analysis and proximal ligation assay

Immunofluorescence analysis was conducted as previous report 19. For proximal ligation assay to detect the interaction of RIP140 with Syk, anti-RIP140 antibody (ab-42126, Abcam) and anti-Syk antibody (626201, Biolegend) were used with Duolink PLA assay kit (Olink Bioscience). Images were acquired by FluoView 1000 IX2 confocal microscope (Olympus).

Syk kinase assay

For in vitro Syk kinase assay, wild type and mutant forms of Flag-RIP140 were purified from transfected 293T cell lysates by immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates were incubated with 10 ng active Syk (Cell Signaling) in Syk kinase assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 2.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1mM EGTA, 0.4 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM DTT and 200 μM ATP) at 25°C for 1h. After reaction, immunoprecipitates were subjected into SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted with anti-phospho-tyrosine.

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was conducted as the instruction of EZ ChIP kit (Millipore) with modifications. Briefly, 1 × 107 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h and then fixed by formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. Cells were then collected and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. Equal amount of cell lysates were used for chromatin immunoprecipitation by anti-p65 (Abcam), anti-acetylated-histone H4 (Millipore) and control IgG (Santa Cruz). DNA was purified by DNA purification column as manufacturer’s instruction (Qiagen). Relative occupancy was determined by quantitative PCR for sample from specific antibody versus control IgG.

Lentivirus production, concentration and transduction

Production and concentration of lentivirus were performed as described previously 21. Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with expression vectors (hCD68 promoter-driven expression of wild type or mutant forms of RIP140) and packing system (System Biosciences). Lentivirus-containing media were collected at 48 and 96 h after transfection. Virus was concentrated by lenti-X concentrator (Clontech). For transduction, 1×106 peritoneal macrophages in 1 ml medium with polybrene (10 μg/ml) were incubated with lentivirus (MOI:50). Cells were spun down at 1,000 × g for 1 h at 25°C and then plated in culture plates. After 16 h, the medium was changed to normal culture medium.

ET, acute septic shock animal model and macrophage reconstitution

For ET animal model, 6~8-week-old male C56BL/6J mice were injected peritoneally with 0.1 μg LPS/25 g body weight. After 16 h, mice were injected with LPS (100 μg/25 g body weight) and D-galactosamine (0.5 mg/g body weight) to induce acute septic shock. Survival was monitored every hour for the next eight hour. For macrophage reconstitution, 8~10-week-old male C56BL/6J mice were injected peritoneally with 200 μl clondronate-containing liposome (Encapsula Nano Sciences) to deplete their macrophages. After 2 day, 5 × 106 primary macrophages were injected peritoneally. 6 h later, mice were injected with LPS (500 μg/25 g body weight) and serum were collected 1 h after LPS injection. Reconstituted peritoneal macrophages were collected from 8~10-week-old male C56BL/6J mice and then transduced by lentivirus to over-express wild type RIP140 or tyrosine mutant RIP140 (Y3F). Transduction was performed twice in 5 day culture. On day 5 of culture, primary macrophages were treated with or without LPS (100 ng/ml). After 24 h, cells were collected and injected peritoneally into macrophage-depleted mice.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented in means ± SD. Statistical analysis was examined by Student’s t test and P value < 0.05 is statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants DK60521, DK54733, DA11190 and K02-DA13926, as well as the Distinguished McKnight University Professorship to L.-N. Wei. P.-C. Ho was funded by a AHA pre-doctoral fellowship. We thank P-T Liu, S. C. Chan, K.-C. Chang, Y.-S. Chuang, A. Smith, C. Korteum and P. Lam for technical help and S. Kaech for critical reading.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

P.-C. Ho designed and conducted most experiments and wrote the manuscript; Y.-C. Tsui performed animal experiments, and analyzed the results; X. Feng conducted animal experiments; D.R. Greaves provided essential reagent; L.-N. Wei supervised and analyzed the research, wrote the manuscript and provided financial support.

References

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill LA. When signaling pathways collide: positive and negative regulation of toll-like receptor signal transduction. Immunity. 2008;29:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011;13:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wen H, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabas I. Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheedy FJ, et al. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansell A, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 negatively regulates Toll-like receptor signaling by mediating Mal degradation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ni1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007;447:972–978. doi: 10.1038/nature05836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Ivashkiv LB. IFN-gamma abrogates endotoxin tolerance by facilitating Toll-like receptor-induced chromatin remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19438–19443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007816107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SH, Park-Min KH, Chen J, Hu X, Ivashkiv LB. Tumor necrosis factor induces GSK3 kinase-mediated cross-tolerance to endotoxin in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:607–615. doi: 10.1038/ni.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan C, Li L, McCall CE, Yoza BK. Endotoxin tolerance disrupts chromatin remodeling and NF-kappaB transactivation at the IL-1beta promoter. J Immunol. 2005;175:461–468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White R, et al. Role of RIP140 in metabolic tissues: connections to disease. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritah A, Christian M, Parker MG. The metabolic coregulator RIP140: an update. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E335–340. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00243.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CH, Chinpaisal C, Wei LN. Cloning and characterization of mouse RIP140, a corepressor for nuclear orphan receptor TR2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6745–6755. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonardsson G, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor RIP140 regulates fat accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8437–8442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401013101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christian M, et al. RIP140-targeted repression of gene expression in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9383–9391. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9383-9391.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho PC, Lin YW, Tsui YC, Gupta P, Wei LN. A negative regulatory pathway of GLUT4 trafficking in adipocyte: new function of RIP140 in the cytoplasm via AS160. Cell Metab. 2009;10:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho PC, Chuang YS, Hung CH, Wei LN. Cytoplasmic receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140) interacts with perilipin to regulate lipolysis. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1396–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho PC, Wei LN. Negative regulation of adiponectin secretion by receptor interacting protein 140 (RIP140) Cell Signal. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mostaqul Huq MD, Gupta P, Wei LN. Post-translational modifications of nuclear co-repressor RIP140: a therapeutic target for metabolic diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:386–392. doi: 10.2174/092986708783497382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huq MD, Ha SG, Barcelona H, Wei LN. Lysine methylation of nuclear co-repressor receptor interacting protein 140. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1156–1167. doi: 10.1021/pr800569c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta P, et al. PKCepsilon stimulated arginine methylation of RIP140 for its nuclear-cytoplasmic export in adipocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho PC, et al. Modulation of lysine acetylation-stimulated repressive activity by Erk2-mediated phosphorylation of RIP140 in adipocyte differentiation. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1911–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zschiedrich I, et al. Coactivator function of RIP140 for NFkappaB/RelA-dependent cytokine gene expression. Blood. 2008;112:264–276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-121699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho PC, Chang KC, Chuang YS, Wei LN. Cholesterol regulation of receptor-interacting protein 140 via microRNA-33 in inflammatory cytokine production. FASEB J. 2011;25:1758–1766. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-179267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clague MJ, Urbe S. Ubiquitin: same molecule, different degradation pathways. Cell. 2010;143:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Natoli G, Chiocca S. Nuclear ubiquitin ligases, NF-kappaB degradation, and the control of inflammation. Sci Signal. 2008;1:pe1. doi: 10.1126/stke.11pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maine GN, Mao X, Komarck CM, Burstein E. COMMD1 promotes the ubiquitination of NF-kappaB subunits through a cullin-containing ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 2007;26:436–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freudenberg MA, Galanos C. Induction of tolerance to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-D-galactosamine lethality by pretreatment with LPS is mediated by macrophages. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1352–1357. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1352-1357.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vats D, et al. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinjyo I, et al. SOCS1/JAB is a negative regulator of LPS-induced macrophage activation. Immunity. 2002;17:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakagawa R, et al. SOCS-1 participates in negative regulation of LPS responses. Immunity. 2002;17:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimitriou ID, et al. Putting out the fire: coordinated suppression of the innate and adaptive immune systems by SOCS1 and SOCS3 proteins. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:265–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamerman JA, Tchao NK, Lowell CA, Lanier LL. Enhanced Toll-like receptor responses in the absence of signaling adaptor DAP12. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:579–586. doi: 10.1038/ni1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han C, et al. Integrin CD11b negatively regulates TLR-triggered inflammatory responses by activating Syk and promoting degradation of MyD88 and TRIF via Cbl-b. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:734–742. doi: 10.1038/ni.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu X, Chakravarty SD, Ivashkiv LB. Regulation of interferon and Toll-like receptor signaling during macrophage activation by opposing feedforward and feedback inhibition mechanisms. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:41–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:692–703. doi: 10.1038/nri2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smale ST. Selective transcription in response to an inflammatory stimulus. Cell. 2010;140:833–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strebovsky J, Walker P, Lang R, Dalpke AH. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) limits NFkappaB signaling by decreasing p65 stability within the cell nucleus. FASEB J. 2011;25:863–874. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-170597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoon CH, Miah MA, Kim KP, Bae YS. New Cdc2 Tyr 4 phosphorylation by dsRNA-activated protein kinase triggers Cdc2 polyubiquitination and G2 arrest under genotoxic stresses. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:393–399. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoo Y, Ho HJ, Wang C, Guan JL. Tyrosine phosphorylation of cofilin at Y68 by v-Src leads to its degradation through ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Oncogene. 2010;29:263–272. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:695–708. doi: 10.1038/ni.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei LN, Hu X, Chandra D, Seto E, Farooqui M. Receptor-interacting protein 140 directly recruits histone deacetylases for gene silencing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40782–40787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vo N, Fjeld C, Goodman RH. Acetylation of nuclear hormone receptor-interacting protein RIP140 regulates binding of the transcriptional corepressor CtBP. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6181–6188. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6181-6188.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rao MK, Wilkinson MF. Tissue-specific and cell type-specific RNA interference in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1494–1501. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.