Abstract

Craniofacial morphology is highly heritable, but little is known about which genetic variants influence normal facial variation in the general population. We aimed to identify genetic variants associated with normal facial variation in a population-based cohort of 15-year-olds from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. 3D high-resolution images were obtained with two laser scanners, these were merged and aligned, and 22 landmarks were identified and their x, y, and z coordinates used to generate 54 3D distances reflecting facial features. 14 principal components (PCs) were also generated from the landmark locations. We carried out genome-wide association analyses of these distances and PCs in 2,185 adolescents and attempted to replicate any significant associations in a further 1,622 participants. In the discovery analysis no associations were observed with the PCs, but we identified four associations with the distances, and one of these, the association between rs7559271 in PAX3 and the nasion to midendocanthion distance (n-men), was replicated (p = 4 × 10−7). In a combined analysis, each G allele of rs7559271 was associated with an increase in n-men distance of 0.39 mm (p = 4 × 10−16), explaining 1.3% of the variance. Independent associations were observed in both the z (nasion prominence) and y (nasion height) dimensions (p = 9 × 10−9 and p = 9 × 10−10, respectively), suggesting that the locus primarily influences growth in the yz plane. Rare variants in PAX3 are known to cause Waardenburg syndrome, which involves deafness, pigmentary abnormalities, and facial characteristics including a broad nasal bridge. Our findings show that common variants within this gene also influence normal craniofacial development.

Main Text

Twin, family, and animal studies have consistently found that inheritance plays an important role in determining craniofacial morphology.1–4 Traditional two-dimensional measuring techniques on photographs or lateral skull radiographs tend to be imprecise because facial landmarks are subject to rotational, positional, and magnification errors.5 However, recent advances in high-resolution three-dimensional imaging technologies have provided the opportunity to better detail the spatial relationship between facial landmarks6 and to determine which genetic variants may influence these parameters.7,8

Facial development is affected in many congenital disorders, such as Down syndrome (MIM 190685), cleft lip and palate (MIM 225060), Prader-Willi syndrome (MIM 176270), and Treacher Collins syndrome (MIM 154500). The genetic basis for many of these disorders has been explored.9 In addition, quantitative trait analyses in nonhumans have identified loci associated with normal craniofacial variation in, for example, mice and baboons.10,11 A recent study has reported that genetic loci involved in nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate are also associated with normal variation. The authors found an association between rs1258763 and interalar width (as measured by two-dimensional photographs) in one sample and rs987525 and bizygomatic distance (determined by magnetic resonance imaging) in a separate sample.12 However, the results were not replicated in the reciprocal populations, which may be due to difficulty in identifying the same facial landmarks with two different image-capture techniques. Still very little is known about which genetic variants affect normal development of the face in general human populations. We have performed a genome-wide association study of normal facial morphology variation in 2,185 15-year-olds and attempted to replicate any genome-wide significant findings in a further 1,622 participants from the same cohort www.AJHG.com.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and their Children (ALSPAC) is a longitudinal population-based birth cohort that recruited pregnant women residing in Avon, UK, with an expected delivery date between 1st April 1991 and 31st December 1992. 14,541 pregnant women were initially enrolled with 14,062 children born.13 Biological samples including DNA have been collected for 10,121 of the children from this cohort. Ethical approval was obtained from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics committee and relevant local ethics committees, and written informed consent was provided by all parents.

Pertinent to the current study, the children were invited to a clinic when they were 15 years old. 5,253 attended, where two high-resolution facial images were taken by Konica Minolta Vivid 900 laser scanners.14 4,747 individuals had usable images (for 506 individuals this part of the assessment was not completed or the scans were of poor quality and consequently excluded).6

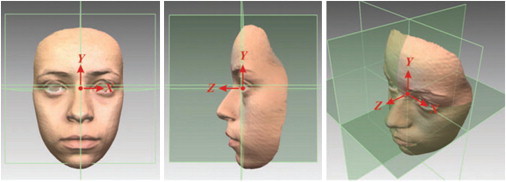

The facial shells were aligned to a common reference frame to facilitate consistency in lighting and orientation prior to undertaking landmark identification. The reference planes had their origin at the midendocanthion, with the sagittal plane (yz) running through the midline of the face, the coronal plane (xy) established as an average natural head posture, and the transverse plane (xz) being horizontal and perpendicular to the sagittal and coronal planes, the x axis lying horizontally from left to right, the y axis directed vertical, and the z axis pointing forward (Figure 1).15 We identified 22 landmarks, 21 on the facial surface6,16 and one constructed midendocanthion point (Figure 2), which has been shown previously to be the most reliable landmark of the face and stable over time.15

Figure 1.

Aligning the 3D Facial Images into Three Reference Planes

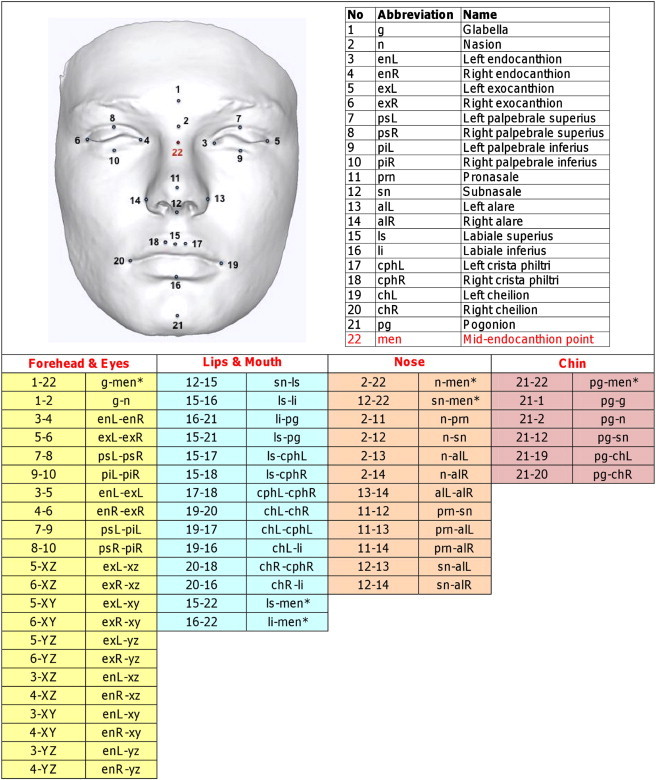

Figure 2.

Position and Definition of the 22 Landmarks and 54 Parameters Analyzed in the Genome-wide Association Discovery Phase

Parameters with pairs of numbers denote the direct 3D distance between pairs of landmarks. Those with “xz,” “xy,” or “yz” denote the prominence of the landmark from the xz, xy, or xz planes. ∗ “men” (point 22) denotes the midendocanthion or midintercanthal point (the midpoint between left and right endocanthi); this point does not lie on the facial surface.

The intra- and interexaminer reliability of these landmarks in the x, y, and z axes have been reported previously, with 89% of the coordinates recording an error of less than 1 mm and 39% of coordinates being within 0.5 mm.6 Fifty-four parameters (3D and 2D distances) characterizing different facial features (e.g., facial height, width, convexity, as well as prominence of landmarks in respect to the facial planes) were generated with the landmark coordinates (Figure 2). All linear measurements are in millimeters. The distributional plots are shown in Figure S1 available online.

To account for the covariance structure present in the data (Table S1), we also performed principal component analysis to determine independent groups of correlated coordinates, as described previously.6 Fourteen principal components were derived (PC1–PC14), explaining 82% of the total variance (Table S2).

3,714 participants were genotyped with either the Illumina 317K or 610K genome-wide SNP genotyping platforms by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (Cambridge, UK) and the Centre National de Génotypage (Evry, France). A common set of SNPs (present in both genotyping platforms) were extracted and the resulting raw genome-wide data were subjected to standard quality control methods. Individuals were excluded on the basis of having incorrect sex assignments; minimal (0.34) or excessive (0.36) heterozygosity; disproportionate levels of individual missingness (>3%); and evidence of cryptic relatedness (PI HAT > 0.11). The remaining individuals were assessed for evidence of population stratification by multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis, with CEU, YRI, JPT, and CHB individuals from the HapMap as reference ethnic groups. Only those clustering with the CEU individuals were included (an MDS plot of included individuals is presented in Figure S2). The underlying population stratification was thereafter controlled for with the first two EIGENSTRAT-derived ancestry informative covariates (EIG-PC1 and EIG-PC2) as well as any additional EIGENSTRAT-derived ancestry informative covariates that were correlated with the phenotype (EIG-PC3 for g-men; EIG-PC9 for exr.XY; EIG-PC4 for prn-alL; EIG-PC10 for ls-pg; EIG-PC5 for PC3; EIG-PC5 for PC11; EIG-PC9 for PC9). SNPs with a minor allele frequency of <0.5% and call rate of <97% were removed. Furthermore, only SNPs that passed an exact test of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > 5 × 10−7) were considered for analysis. The resulting data set consisted of 3,233 individuals and 285,531 SNPs. We then conducted imputation with MACH 1.0 Markov Chain Haplotyping software,17 with CEU individuals from phase 2 of the HapMap project as a reference set (release 22). The final imputed data set consisted of 3,233 subjects, each with 2,543,887 imputed autosomal markers. Only imputed genotypes with minor allele frequencies >1% and R-sqr > 0.3 were considered for association. Of these 3,233 with genetic data, 2,185 participants (1,080 males and 1,105 females) also had facial data available. The participants' mean age was 15 years, 4 months (with a standard deviation of 3 months).

We conducted discovery-phase genome-wide association analysis (n = 2,185) for the 54 facial distances and 14 principal components with 2,543,887 autosomal imputed expected SNP dosages with linear regression (adjusted for sex, EIG-PC1, EIG-PC2, plus any additional ancestry informative covariates as appropriate) in Mach2QTL.17 Although it is true that regressing a phenotype on expected allelic dosage will tend to be conservative, this effect is likely to be minimal, particularly at SNPs that have been imputed well.18 Indeed, the genomic inflation factor was similar regardless of whether imputed or genotyped SNPs were used to calculate λ and whether ancestry informative principal components were included in the regression equation.

We identified four associations reaching the traditional threshold for genome-wide significance (defined as p < 5 × 10−8) with three of the 3D distances (Table 1), with one (rs7559271 and n-men) reaching a stringent Bonferroni corrected threshold of p < 9 × 10−10 after adjusting for the 54 distances tested. All results for associations with p < 5 × 10−7 are shown in Table S3. There was little genomic inflation, with λ ranging from 1.00 to 1.02 for these three phenotypes (λ = 1.00 for all three in genotyped SNPs only and before ancestry EIG-PC adjustment, QQ plot for n-men is shown in Figure S3). Though we analyzed 54 distances, many of these are correlated (Table S1) and so a Bonferroni correction would be conservative. Therefore, we attempted to replicate all four associations with p < 5 × 10−8. No genome-wide significant associations were observed for any of the principal components (PCs) (Table S3). We examined the associations between rs7559271 and each of the principal components to see whether this SNP was just below the genome-wide significant threshold for any of the PCs. rs7559271 showed modest associations with PC5 (p = 2 × 10−4) and PC11 (p = 6 × 10−6) (Table S4). These PCs describe prominence of the eyes relative to the nasal bridge and prominence of the upper eyelids (Table S2) and so are relevant, but a GWAS of these PCs alone would fail to identify this SNP from the noise further down in the p value distribution. Although principal components capture information on covariance between traits and so would be successful in identifying genes that influence these correlated traits, if a genetic variant has a very specific localized effect (as in the case of rs7559271), then this effect will be diluted in a PC analysis.

Table 1.

Discovery Phase and Replication Phase Results for the Four Associations with p < 5 × 10−8 in the Discovery Phase

| Distance | Mean | SD | SNP | Chr:position | Gene | Effect:Alt Allele | Effect Allele Freq |

Discovery (n = 2,185); 49% Male; Mean Age 15yr4m (SD = 3 m) |

Replication (n = 1,622); 46% Male; Mean Age 15yr4m (SD = 3 m) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | p Value | Beta | SE | p Value | ||||||||

| enR.yz | 17.081 | 1.510 | rs10862567 | 12:81946438 | TMTC2 | T:A | 0.31 | 0.181 | 0.033 | 4.4 × 10−8 | 0.024 | 0.035 | 0.506 |

| n-men | 17.505 | 2.341 | rs7559271 | 2:222776530 | PAX3 | G:A | 0.38 | 0.169 | 0.027 | 2.2 × 10−10 | 0.161 | 0.032 | 4.0 × 10−7 |

| prn-alL | 26.596 | 1.896 | rs1982862 | 3:55039780 | CACNA2D3 | C:A | 0.88 | 0.257 | 0.046 | 1.8 × 10−8 | 0.067 | 0.049 | 0.167 |

| prn-alL | 26.596 | 1.896 | rs11738462 | 5:61046695 | C5orf64 | G:A | 0.83 | 0.204 | 0.036 | 1.8 × 10−8 | −0.025 | 0.039 | 0.527 |

Means and standard deviations (SDs) are in mm, betas are in standard deviations (per effect allele). Imputation quality scores for the four SNPs are rs10862567 (r2 = 0.96), rs7559271 (r2 = 1.00), rs1982862 (r2 = 0.80), and rs11738462 (r2 = 1.00).

Because only 2,185 of the available 4,747 facial scans were used in the discovery phase, we used the remainder of these and data from a subsequent genome-wide scan on the entire ALSPAC cohort for replication. 9,912 participants were genotyped with the Illumina HumanHap550 quad genome-wide SNP genotyping platform by 23andMe subcontracting the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (Cambridge, UK) and the Laboratory Corporation of America (Burlington, NC, US). Individuals were excluded on the basis of having incorrect sex assignments; minimal or excessive heterozygosity (<0.32 and >0.345 for the Sanger data and <0.31 and >0.33 for the LabCorp data); disproportionate levels of individual missingness (>3%); evidence of cryptic relatedness (>10% IBD); and being of non-European ancestry. The resulting data set consisted of 8,365 individuals. SNPs with a minor allele frequency of <1%, call rate of <95%, or not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibirum were removed. Genotypes were subsequently imputed, as before. Much stricter ethnicity inclusion criteria were used in the replication sample (see Figure S2) and so no ethnicity covariates were included in the replication analysis model. Of the 8,365 ALSPAC genotyped individuals, 1,622 (750 males, 872 females) also had facial data and were not included in the discovery sample. The participants' mean age was 15 years 4 months (with a standard deviation of 3 months).

Because four associations were tested in replication, applying a Bonferroni correction for this phase would yield α = 0.0125. The association between the nasion to midendocanthion distance and rs7559271 on chromosome 2q36.1 replicated strongly (p = 4.0 × 10−7) (Table 1). Soft-tissue nasion is defined as the deepest point on the nasal bridge (point 2 on Figure 2). The midendocanthion is the midpoint between the left and right endocanthi (point 22 on Figure 2). To further investigate the association between n-men and rs7559271, we combined the discovery and replication samples and carried out linear regression analysis in STATA v11.2. In an analysis combining the discovery and replication samples, the G allele of rs7559271 was associated with an increase in this 3D measure of 0.388 mm (SE = 0.047, p = 4.1 × 10−16) or 0.166 standard deviations, with this variant explaining 1.3% of the variance (Table 2). Analyses stratified by sex gave similar results (β = 0.428 mm, SE = 0.071, p = 2.1 × 10−9 for males and β = 0.350 mm, SE = 0.063, p = 4.0 × 10−8 for females), indicating that there was no sex-by-genotype interaction.

Table 2.

The Association between rs7559271 and the Distances and Angles Relating to the n-men Distance on the Face in the Combined Sample of 3,807 Participants

| Phenotype | Dimension | Mean | Standard Deviation | Interpretation | Covariates | Beta | SE | p Value | % Variance Explained by SNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-men 3D dist | xyz | 17.507 | 2.343 | sex | 0.388 | 0.047 | 4.1 × 10−16 | 1.3 | |

| n-men 1D dist | x | 0.573 | 0.452 | absolute lateral distance of nasion from men | sex | 0.029 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.2 |

| sex; y dist; z dist | 0.033 | 0.011 | 0.002 | ||||||

| n-men 1D dist | y | 9.184 | 2.324 | height of nasion above men | sex | 0.291 | 0.053 | 5.3 × 10−8 | 0.8 |

| sex; z dist; x dist | 0.309 | 0.054 | 9.1 × 10−9 | ||||||

| n-men 1D dist | z | 14.698 | 2.386 | prominence of nasion relative to men | sex | 0.272 | 0.046 | 4.4 × 10−9 | 0.6 |

| sex; y dist; x dist | 0.286 | 0.046 | 8.5 × 10−10 | ||||||

| n-men 2D dist | yz | 17.492 | 2.344 | prominence and height of nasion | sex | 0.390 | 0.047 | 3.1 × 10−16 | 1.3 |

| n-men z.yz angle | yz | 32.032 | 7.817 | angle between the yz vector and z axis | sex | 0.360 | 0.171 | 0.036 | 0.1 |

Distances are in mm (with betas, mm per G allele) and angles are in degrees (with betas, degrees per G allele).

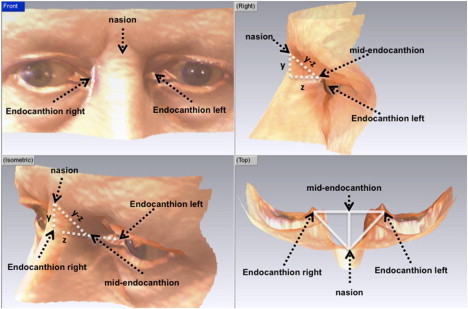

Variation in the 3D n-men distance may be driven by one-dimensional distances (and/or angles). Therefore, we deconstructed the n-men 3D distances into one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) distances and carried out exploratory analyses to investigate in which dimension(s) the associations were having an effect (Figure 3). A strong association was observed in the y distance (p = 5.3 × 10−8), which reflects height of the nasion relative to the midendocanthion, and the z distance, reflecting the prominence of nasion relative to men (p = 4.4 × 10−9) (Table 2). In contrast, there was much weaker association between rs7559271 in the x distance (p = 0.006), which reflects the lateral distance of nasion relative to the midendocanthion. Conditional analyses showed that the associations in the y and z dimensions were independent of each other and that there was only weak evidence of association between the SNP and yz angle between the nasion and midendocanthion. These results suggest that the association between rs7559271 and the 3D n-men distance is being mostly driven by the distance in the yz plane.

Figure 3.

Deconstruction of the 3D n-men Phenotype into Its Constituent One-Dimensional Distances

The midendocanthion is defined as the midpoint between the left and right endocanthi and is therefore not a surface point. The 3D nasion-midendocanthion (n-men) distance was deconstructed into the three 1D distances: the x (the lateral distance between the nasion and midendocanthion—a measure of how off-center the nasion is relative to the midendocanthion), the y (the vertical distance between the nasion and midendocanthion), and the z (the prominence of the nasion relative to the midendocanthion). The 2D yz distance was also constructed as was the angle between the yz and z components.

We used the Procrustes registration procedure with scaling19,20 to generate scaled n-men distances (3D) for individuals (adjusted for overall face size), and the association between rs7559271 and this scaled measure gave very similar results (β = 0.397, SE = 0.046, p = 1.0 × 10−17 in the combined analysis) to the unscaled analysis. rs7559271 was associated with only 1 of the other 53 unscaled measures (g-n, β = 0.122, SE = 0.022, p = 3.6 × 10−8) and was not associated with height or tanner score of puberty21 (data not shown). Adjusting for any of these phenotypes in the association with n-men did not attenuate the association (data not shown) and so the association does not appear to be driven by overall face or total body size.

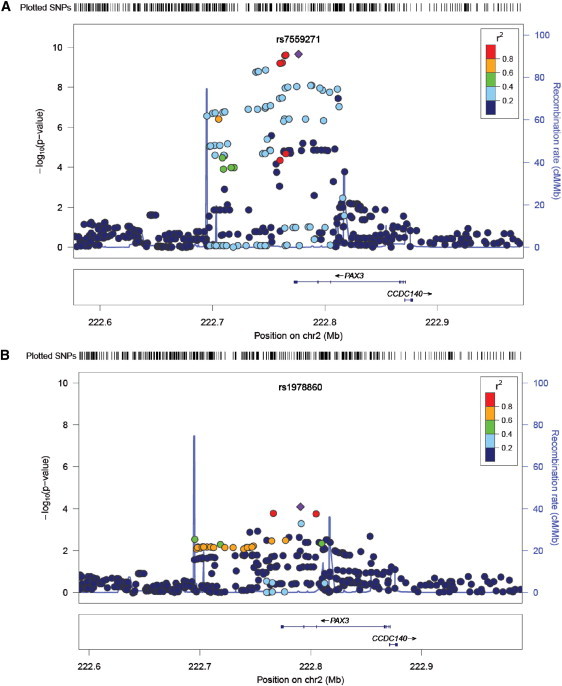

There was also evidence for a second independent signal in this region (Figure 4). After conditioning on rs7559271, the C allele of rs1978860 remained associated with n-men in the discovery sample (β = 0.355, SE = 0.09, p = 8.1 × 10−5). This association was replicated (β = 0.281, SE = 0.118, p = 0.017), although it did not reach genome-wide significance overall (β = 0.385, SE = 0.077, p = 6.5 × 10−7). Unlike the rs7559271 signal, this signal appears to be mostly driven by the distance in the z plane (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Association Plot of the Region Surrounding PAX3 for the Nasion-to-Midendocanthion Distance in the Discovery Phase

(A) The discovery results.

(B) Evidence of a second independent signal in the region—results after adjusting for the top hit (rs7559271) in the discovery data.

Produced with LocusZoom. Linkage disequilibrium (r2) is illustrated by color of the points (see key).

Table 3.

The Association between rs1978860 and the Distances and Angles Relating to the n-men Distance on the Face after Adjusting for rs7559271 in the Combined Sample of 3,807 Participants

| Phenotype | Dimension | Beta | SE | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-men 3D dist | xyz | 0.385 | 0.077 | 6.5 × 10−7 |

| n-men 1D dist | x | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.122 |

| n-men 1D dist | y | 0.195 | 0.087 | 0.025 |

| n-men 1D dist | z | 0.338 | 0.075 | 7.7 × 10−6 |

| n-men 2D dist | yz | 0.384 | 0.077 | 6.9 × 10−7 |

| n-men z.yz angle | yz | −0.018 | 0.279 | 0.949 |

Betas are in mm (for the distances) or degrees (for the angle) per C allele.

rs7559271 (and rs1978860) are intronic SNPs in PAX3 (paired box 3, MIM 606597). This gene encodes a transcription factor that plays a crucial role in fetal development. PAX3 was identified as being involved in Waardenburg syndrome (WS) Type I (MIM 193500) after the identification of a patient with a de novo inversion (inv[2][q35q37.3]).22 Approximately 85 different PAX3 point mutations have now been identified in Type I and Type III (MIM 148820) WS patients, approximately half of which are missense and half of which are truncating variants, and most of which are extremely rare.23 This syndrome affects ∼1 in 42,000 births24 and is characterized by deafness; hair, skin, and eye pigmentation abnormalities; as well as (specifically for Type I WS) characteristic facial features such as broad, high nasal root and wide spacing of the endocanthion of the eyes (telecanthus).25 We therefore investigated the association between the common PAX3 variant (rs7559271) and intercanthal width. Though this SNP is associated with the enL-n-enR angle (p = 7.6 × 10−13), it is not associated with the distance between the eyes (enL-enR, p = 0.847, Figure S4), demonstrating that the association is driven by the yz n-men vector and not the position of the endocanthi, in contrast to what is seen in people with rare PAX3 mutations resulting in WS.

We attempted to replicate the findings of a recent study investigating the role of nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate genetic variants on normal facial morphology.12 We found no association between rs1258763 and interalar width (alL-alR) in our sample (T allele β = −0.008, p = 0.774). Inconsistent results between studies could be explained by many factors, such as differences in the method of image capture and its resolution26 (the association in the previous study was observed with two-dimensional digital photographs), differences in methods of feature assessment for landmark definitions,6 inaccuracy in determining landmark positions or methods for determining parameters, and differences in age,14 gender,27 or ethnicity28 of the populations studied. We had no zygomatic landmarks and so could not attempt to replicate their other finding.

In summary, in this genome-wide association study of facial morphology, we have identified an association between rs7559271 and nasion position in a population cohort of 15-year-old adolescents. This SNP is within an intron of PAX3. Many rare variants in this gene have been associated with Waardenburg syndrome, which has symptoms including wide spacing of the endocanthi. Therefore, it is of interest that we now report that common variants in this gene are also associated with prominence and vertical position of the nasion in the general population, although these facial characteristics are different to those reported in Waardenburg syndrome.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the individuals who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses. We thank the Sanger Centre, Centre National de Génotypage, and 23andMe for generating the ALSPAC GWA data. The publication is the work of the authors and L.P. will serve as guarantor for the contents of this paper. The UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust (grant ref: 092731), and the University of Bristol provide core support for the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and their Children. The collection of the face data was funded by ALSPAC and Cardiff University. L.P., D.M.E., and this work were supported by a Medical Research Council New Investigator Award (MRC G0800582 to D.M.E.). A.M.T. was funded by a Cardiff University 3-year PhD program. J.P.K. was funded by a Wellcome Trust 4-year PhD studentship in molecular, genetic, and life course epidemiology (WT083431MA).

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

ALSPAC, http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/

LocusZoom, http://csg.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

References

- 1.Kohn L.A.P. The role of genetics in craniofacial morphology and growth. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1991;20:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter W.S., Balbach D.R., Lamphiear D.E. The heritability of attained growth in the human face. Am. J. Orthod. 1970;58:128–134. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakata N., Yu P.I., Davis B., Nance W.E. The use of genetic data in the prediction of craniofacial dimensions. Am. J. Orthod. 1973;63:471–480. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(73)90160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johannsdottir B., Thorarinsson F., Thordarson A., Magnusson T.E. Heritability of craniofacial characteristics between parents and offspring estimated from lateral cephalograms. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.07.033. quiz 260–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson P.E., Richmond S. A critical appraisal of measurement of the soft tissue outline using photographs and video. Eur. J. Orthod. 1997;19:397–409. doi: 10.1093/ejo/19.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toma A.M., Zhurov A.I., Playle R., Marshall D., Rosin P.L., Richmond S. The assessment of facial variation in 4747 British school children. Eur. J. Orthod. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr106. in press. Published online September 20, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klingenberg C.P. Evolution and development of shape: integrating quantitative approaches. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:623–635. doi: 10.1038/nrg2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leamy L.J., Klingenberg C.P., Sherratt E., Wolf J.B., Cheverud J.M. A search for quantitative trait loci exhibiting imprinting effects on mouse mandible size and shape. Heredity (Edinb) 2008;101:518–526. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochheiser H., Aronow B.J., Artinger K., Beaty T.H., Brinkley J.F., Chai Y., Clouthier D., Cunningham M.L., Dixon M., Donahue L.R. The FaceBase Consortium: a comprehensive program to facilitate craniofacial research. Dev. Biol. 2011;355:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh J., Wang C.J., Poole M., Kim E., Davis R.C., Nishimura I., Pae E.-K. A genome segment on mouse chromosome 12 determines maxillary growth. J. Dent. Res. 2007;86:1203–1206. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherwood R.J., Duren D.L., Havill L.M., Rogers J., Cox L.A., Towne B., Mahaney M.C. A genomewide linkage scan for quantitative trait loci influencing the craniofacial complex in baboons (Papio hamadryas spp.) Genetics. 2008;180:619–628. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehringer S., van der Lijn F., Liu F., Günther M., Sinigerova S., Nowak S., Ludwig K.U., Herberz R., Klein S., Hofman A. Genetic determination of human facial morphology: links between cleft-lips and normal variation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:1192–1197. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golding J., Pembrey M., Jones R., ALSPAC Study Team ALSPAC-the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. I. Study methodology. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2001;15:74–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kau C.H., Richmond S. Three-dimensional analysis of facial morphology surface changes in untreated children from 12 to 14 years of age. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:751–760. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhurov A.I., Richmond S., Kau C.H., Toma A. Averaging facial images. In: Kau C.H., Richmond S., editors. Three-Dimensional Imaging for Orthodontics and Maxillofacial Surgery. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2010. pp. 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toma A.M., Zhurov A., Playle R., Ong E., Richmond S. Reproducibility of facial soft tissue landmarks on 3D laser-scanned facial images. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2009;12:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2008.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y., Willer C.J., Ding J., Scheet P., Abecasis G.R. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet. Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng J., Li Y., Abecasis G.R., Scheet P. A comparison of approaches to account for uncertainty in analysis of imputed genotypes. Genet. Epidemiol. 2011;35:102–110. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gower J.C. Generalized Procrustes analysis. Psychometrika. 1975;40:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dryden I.L., Mardia K.V. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 1998. Statistical Shape Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanner J. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford, UK: 1962. Growth at Adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsukamoto K., Tohma T., Ohta T., Yamakawa K., Fukushima Y., Nakamura Y., Niikawa N. Cloning and characterization of the inversion breakpoint at chromosome 2q35 in a patient with Waardenburg syndrome type I. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1992;1:315–317. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.5.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pingault V., Ente D., Dastot-Le Moal F., Goossens M., Marlin S., Bondurand N. Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:391–406. doi: 10.1002/humu.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waardenburg P.J. A new syndrome combining developmental anomalies of the eyelids, eyebrows and nose root with pigmentary defects of the iris and head hair and with congenital deafness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1951;3:195–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Read A.P., Newton V.E. Waardenburg syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1997;34:656–665. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.8.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kau C.H., Richmond S., Zhurov A.I., Knox J., Chestnutt I., Hartles F., Playle R. Reliability of measuring facial morphology with a 3-dimensional laser scanning system. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bo Ic M., Kau C.H., Richmond S., Hren N.I., Zhurov A., Udovič M., Melink S., Ovsenik M. Facial morphology of Slovenian and Welsh white populations using 3-dimensional imaging. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:640–645. doi: 10.2319/081608-432.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kau C.H., Richmond S., Zhurov A., Ovsenik M., Tawfik W., Borbely P., English J.D. Use of 3-dimensional surface acquisition to study facial morphology in 5 populations. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137(4, Suppl) doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.04.022. S56, e1–e9, discussion S56–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.