Abstract

Intellectual disability (ID) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous common condition that remains etiologically unresolved in the majority of cases. Although several hundred diseased genes have been identified in X-linked, autosomal-recessive, or syndromic types of ID, the establishment of an etiological basis remains a difficult task in unspecific, sporadic cases. Just recently, de novo mutations in SYNGAP1, STXBP1, MEF2C, and GRIN2B were reported as relatively common causes of ID in such individuals. On the basis of a patient with severe ID and a 2.5 Mb microdeletion including ARID1B in chromosomal region 6q25, we performed mutational analysis in 887 unselected patients with unexplained ID. In this cohort, we found eight (0.9%) additional de novo nonsense or frameshift mutations predicted to cause haploinsufficiency. Our findings indicate that haploinsufficiency of ARID1B, a member of the SWI/SNF-A chromatin-remodeling complex, is a common cause of ID, and they add to the growing evidence that chromatin-remodeling defects are an important contributor to neurodevelopmental disorders.

Main Text

Intellectual disability (ID) is a severely incapacitating condition that imposes a significant burden on affected individuals and their families. The incidence is estimated at 2%–3%, and severe forms (intelligence quotient [IQ] < 50) account for about 0.5% of all newborns. It is now accepted, at least in developed countries, that the vast majority of cases are of genetic origin.1 Some 10% of affected boys are estimated to have an X-linked condition, and in about 80% of X-linked families, the underlying genetic defect has now been uncovered through systematic sequencing of all X-chromosomal coding segments.1,2 Autosomal-recessive forms are amenable to positional cloning in consanguineous families, and this strategy has recently led to the identification of an important number of genes harboring recessive mutations.3,4 Investigating sporadic cases from nonconsanguineous couples is more difficult, but the discovery of several genes involved has been enabled by either synaptic candidate-gene approaches or the de novo occurrence of copy-number variants (CNVs) or chromosomal translocations.5–8 Whole-exome sequencing in 10 and 20 trios confirmed the power of this technique to identify ID-associated genes, and several studies proposed that many sporadic cases might arise from de novo mutations.9,10 Despite important advances in identifying the underlying genes, some 50% of all cases and the vast majority of unspecific patients remain undiagnosed.11 This is probably a result of the enormous locus heterogeneity because most genes with autosomal-dominant mutations only account for a few cases each.

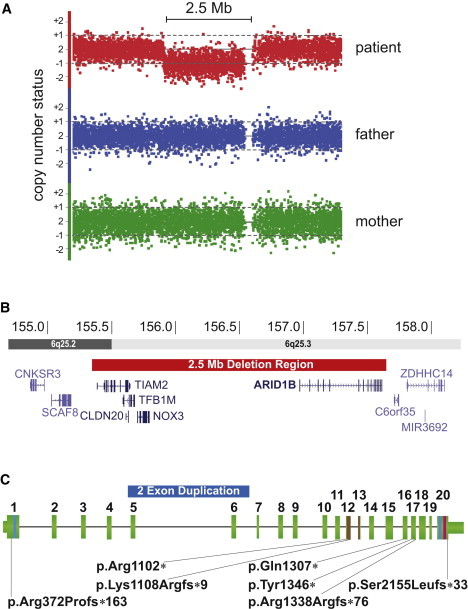

The German Mental Retardation Network (MRNET) aims to systematically uncover the genetic basis of ID. Over several years, we recruited from eight different medical-genetics centers a large study group of affected individuals mostly of German origin. The study was approved by all institutional review boards of the participating institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. We screened 1,986 of the individuals with array-based molecular karyotyping by using high-resolution platforms. In one male infant, we identified a 2.5 Mb deletion containing five genes in chromosomal region 6q25.3 (Figure 1) by using the high-resolution Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California) and the Affymetrix Genotyping Console Software (version 3.0.2). Segregation analysis of both parents revealed a de novo origin of the deletion. The familial relationship was confirmed. Because the phenotype of our patient resembled that of the patients with larger deletions,12 we hypothesized that one of the five deleted genes would show haploinsufficiency and would represent a phenocritical gene responsible for the ID.

Figure 1.

Summary of the Nine De Novo CNVs and Point Mutations Detected in ARID1B

(A) De novo deletion in patient 1 detected with molecular karyotyping by the Affymetrix SNP6.0 platform. The signal reduction of 1,568 markers indicating the deletion region is detected only in patient 1 (red dots) and is absent in both parents.

(B) 2.5 Mb deletion (red bar) in chromosomal region 6q25, which includes five RefSeq genes, among them ARID1B. Two gray scales are illustrating two different chromosomal bands as indicated in the horizontal bars. Genomic positions are in million bp.

(C) Genomic structure of ARID1B. Vertical green bars illustrate the exons with their respective number above. Narrow green bars illustrate the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. The three known ARID1B domains are indicated by colored lines (blue, LXXLL; brown, ARID; and magenta, BC-Box). The duplication in patient 2 is indicated by a blue bar encompassing exons 5 and 6. The localization of mutations in patients 3–9 is indicated by black lines leading to the mutation identifiers.

Using Sanger sequencing, we screened all five genes from this region, including TFB1M (MIM 607033), NOX3 (MIM 607105), and three brain-expressed genes, TIAM2 (MIM 604709), CLDN20, and ARID1B, for point mutations in 121 individuals with moderate to severe ID without a known genetic cause; these individuals were from the Erlangen subgroup of the German Intellectual Disability Network (MRNET). Microarray analyses for CNVs >200 kb had been previously performed in 82 (68%) of the individuals, and no obvious pathogenic CNV was found. For sequencing, we used Applied Biosystems (ABI) BigDye Terminator chemistry and purification with Agencourt AMPure and CleanSEQ kits (Beckman-Coulter) on an ABI 3730 sequencer with Sequencing Analysis v.3.6.1 (Applied Biosystems) and Sequencher 4.9 (Gene Codes Corporation) software packages. Although no mutation was detected in TFB1M, NOX3, TIAM2, or CLDN20, we identified a c.3919C>T (p.Gln1307∗) nonsense mutation in exon 16 of ARID1B in patient 3 and an 11 bp deletion in exon 20 of ARID1B (NM_020732.3) in patient 4; the latter mutation (c.6463_6473del [p.Ser2155Leufs∗33]) lead to a frameshift and a premature termination codon after 33 residues. We used original, nonamplified DNA samples for independent PCR and bidirectional sequencing to confirm the mutations. In addition, we reanalyzed the genomic region of ARID1B for CNVs <200 kb in this subgroup, and we detected in another patient a 180 kb duplication encompassing exons 5 and 6 (hg18 chr6: 157,299,982–157,474,352). Using the SALSA multiple ligation probe amplification (MLPA) reagents EK5 (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and copy-number calculation with Seqpilot software (JSI Medical Systems, Kippenheim, Germany), we confirmed this mutation by MLPA with customized probes for exons 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (Table S3, available online). We studied a common SNP in exon 6 by using cDNA generated from RNA isolated from fresh blood leukocytes with the PAXgene Blood RNA System (PreAnalytics) in conjunction with the Superscript Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen) and random hexamers. This analysis revealed that the duplication arose on the paternal allele and led to monoallelic expression of the wild-type allele (Figure 2A). Analysis of parental DNA confirmed the biological relationships and revealed that all mutations arose de novo. Given that all mutations occurred de novo and were predicted to cause loss of function, we hypothesized that haploinsufficiency of ARID1B would underlie the ID in patients with 6q25.3 microdeletion syndrome.

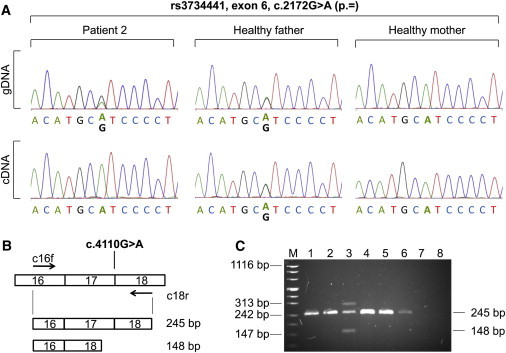

Figure 2.

Transcript Analysis for the ARID1B Mutations in Patients 2 and 7

(A) Partial sequence electropherograms of ARID1B exon 6 obtained from gDNA and cDNA from patient 2 with a de novo duplication of exons 5 and 6 and his healthy parents. Patient 2 and his father are heterozygous for rs3734441 (c.2172G>A on exon 6) at the gDNA level. Note that the amount of guanine is doubled in the patient. At the cDNA level, the father shows biallelic expression, whereas monoallelic expression of adenine in patient 2 indicates that the duplication leads to a null allele.

(B and C) Synonymous variant in the last codon of exon 17 induces exon skipping of exon 17 in patient 7. Using primers located in exons 16 and 18 (c16f and c18r, respectively), indicated by arrows for RT-PCR on RNA from peripheral blood leukocytes, resulted in an additional aberrant product of 148 bp in the patient (lane 3), whereas both parents (lanes 1 and 2) and controls (lanes 4–6) showed only the expected 245 bp fragment (lane 7, genomic DNA control; lane 8, no template control; M, size standard). Exon skipping in the patient was verified by the sequencing of amplified products and is predicted to result in a frameshift and premature stop codon after 76 amino acids (p.Arg1338Argfs∗76). In the patient's lane, an additional third band with a molecular size of ∼310 bp represents a heteroduplex.

Given the relatively high frequency of mutations identified in the first subgroup, we extended the mutation screen (consisting of exons 2–20, including flanking intronic regions) to another 766 ID-affected individuals from the MRNET consortium (for a detailed description of the study group, see supplemental data). As a result of its high GC content, we amplified exon 1 with the Fast Amplification Kit (QIAGEN) by using a set of nested PCR fragments with different sequencing primers (Table S4). In this group, we further identified four nonsense mutations and one synonymous variant in the last base pair of exon 17; these mutations are predicted to affect the consensus splice donor site (Table 1 and Table S1). The skipping of exon 17 was confirmed by RT-PCR from RNA extracted from the patients' blood (Figures 2B and 2C) and was predicted to cause a frameshift resulting in a premature translational termination (p.Arg1338Argfs∗76). All mutations were shown to have occurred de novo, and the parental relationships were confirmed by a forensic set of microsatellites (Promega) in all instances. These mutations confirmed the initial hypothesis of the causative role of ARID1B in ID and increased the total number of bona fide mutations to eight (0.9%) in the entire cohort of 887 individuals. In addition, we observed 101 unique variants not annotated in dbSNP (build 132) (Table S1). We investigated segregation in 18 out of 23 cases with missense variants—when parental material was available—and could show segregation from a healthy parent (10 maternal and 8 paternal) in all instances. The remaining five variants are not located in any known domain and were not suspicious when investigated with various prediction programs (Table S2), suggesting that these 23 missense variants are benign. However, we cannot exclude some milder effect on protein function. Our findings thus indicate that ARID1B-haploinsufficiency-causing mutations, but not missense variants, are a common cause of ID. This association is further supported by recent reports on microaberrations affecting ARID1B. One case with a frameshift intragenic 281 kb deletion affecting the ARID domain was reported in a patient with autism,13 a complex chromosomal translocation leading to a fusion gene of ARID1B and MRPP3 was found in an individual with ID,14 and one translocation, four larger deletions (including ARID1B), and 3 intragenic deletions were reported by Halgren et al.15 in patients with ID.

Table 1.

Clinical Data from Patients with ARID1B Deletions or Mutations

| Nagamani et al.12(N = 4) | Halgren et al.15(N = 8) | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARID1B defect | deletion of several genes, including ARID1B | one translocation, four larger deletions (including ARID1B), and three intragenic deletions | deletion of five genes (chr6: 155,364,154–157,681,073∗) | duplication of exons 5 and 6 (chr6: 157,299,982–157,474,352∗) | c.3919C>T (p.Gln1307∗) | c.6463_6473del (p.Ser2155Leufs∗33) | c.3304C>T (p.Arg1102∗) | c.3323_3324delAA (p.Lys1108Argfs∗9) | c.4110G>A (p.Arg1338Argfs∗76) | c.4038T>A (p.Tyr1346∗) | c.1114 dupC (p.Arg372Profs∗163) |

| Inheritance | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo |

| Sex | 2 F, 2 M | 6 F, 2 M | F | F | M | M | F | F | F | M | M |

| Age at last follow-up examination | 10–33 months | 3–46 years | 3 years, 3 months | 4 years, 11 months | 3 years, 5 months | 7 years, 3 months | 12 years, 8 months | 4 years | 6 years, 3 months | 17 years | 20 years |

| Birth parameters (weight, length, OFC) | 3 ≤ 3rd ct 2 ≤ 5th ct 3 < 3rd ct | 3/7 ≤ 10th ct 5/6 ≤ 10th ct 5 ≤ 10th ct | 50th ct 3rd−10th ct 50th−75th ct | 25th ct 50th ct 25th ct | 50th ct 25th ct 25th ct | 50th ct 50th ct 50th ct | 25th ct 25th ct 50th ct | 3rd−10th ct 50th ct 3rd−10th ct | 50th−75th ct >97th ct 75th ct | 10th−50th ct 50th ct 10th−50th ct | 10th ct 50th ct 50th ct |

| Length and/or height and OFC | 2/4 < 3rd ct 4/4 < 3rd ct | 7/7 ≤ 5th ct 1/5 < 3rd ct | 10th ct 10th−25th ct | 3rd−10th ct <3rd ct | 3rd−10th ct 50th ct | <3rd ct 25th−50th ct | <3rd ct 25th –50th ct | 10th−25th ct 75th ct | 25th−50th ct 75th ct | 50th ct >97th ct | <3rd ct <3rd ct |

| Developmental delay | 4/4 | 8/8 | severe | moderate | severe | moderate IQ = 50 (tested) | severe | mild to moderate | moderate to severe | moderate | moderate |

| Speech | 1/4 spoke two words at 33 months | 8/8 were severely impaired or absent | – | first words at 3–4 years and sentences at 4 years, 11 months | single words | – | first words at >5 years and two-word sentences at 12 years | at age of 24 months, corresponding to age of 17 months | single words | short sentences and sufficient working vocabulary | delayed |

| Age of walking | 1/4 at 23 months | 1/1 at 30 months | 28 months | 24 months | 20 months | + | 27 months | 24 months | 24 months | 18 months | 20 months |

| Muscular hypotonia | 2/4 | 7/7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | – |

| MRI scan anomaly | 2/3 (2 with ACC) | 4/5 with ACC or HCC | retrocerebellar cyst | delayed myelination | NA | – | – | NA | asymmetric calvaria | NA | – |

| Seizures | 1/4 | 3/7 | – | – | – | – | +∗∗ | – | +∗∗ | + | – |

| Hearing loss | 4/4 | ? | – | – | – | – | + (unilateral) | – | – | – | – |

| Heart malformation | 1/4 (ASD) | ? | – | + | – | + (ASD) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cleft palate | 0/4 with cleft palate and 2/4 with palatal anomalies | ? | – | – and high palate | – | + | + | – | – and high palate | – | – |

| Abnormal shape of head | 3/4 with plagiocephaly | 5/5 with low hairline | plagiocephaly and frontal bossing | plagiocephaly and frontal bossing | prominent forehead | – | brachycephaly and low forehead | frontal bossing | low forehead | – | brachycephaly |

| Low-set and/or posteriorly rotated ears | 4/4 | 2/2 | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| Abnormally shaped ears | 2/4 | ? | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | + |

| Downslanting palpebral fissures | 2/4 | ? | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| Strabism | + | 2 | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bulbous nasal tip | 3/3 | 3/3 | + | + | – | + | +/– | +/− | + | – | – |

| Thin upper lip | 2/4 | 3/4 | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Teeth anomalies | ? | ? | – | small and pointed | pointed | small | first teeth small and widely spaced | – | small | malocclusion and delayed second dentition | NA |

| Retro/micrognathia | 2/3 | ? | + | + | – | – | – | + | - | + | – |

| Hand and feet anomalies | 1/4 with clinodactyly and 0/4 with single palmar crease | ? | – | single palmar creases and brachydactyly V | brachydactyly | single palmar creases, sandal gaps, and hypoplastic nails | sandal gaps, clinodactyly V, and hypoplastic toe nails V | long toes | – | – | single palmar creases, clinodactyly V, deep set thumbs, and Hallux valgus |

| Other abnormalities | 2/4 with retinal anomalies; 1/4 with genitourinary anomaly | 5/7 with AuSD or autistic traits, 4 with myopia/hypermetropia, 1 with cataracts, 4 with hypertrichosis, and 5 with feeding problems | clitoris hypertrophy and long philtrum | ataxic gait, sparse hair, sacral dimple, and three hemangiomas | allergy, recurrent infections, autistic features, and aggression | cryptorchism and myopia | allergy, myopia, megaureter, wide mouth, dry hair, and hypothyreosis | hypertrichosis and myopia | hypertrichosis | myopia, skin hypopigmentation, and hypertelorism | unilateral myopia, blocked nasolacrimal duct, dermoid cyst, atlanto/occipital abnormalities, discreet rhizomelic shortening of arms and legs, scoliosis, and cryptorchism |

The following abbreviations are used: N, number of patients; F, female; M, male; ct, percentile; OFC, occipital-frontal circumference; IQ, intelligence quotient; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; +, present; –, absent; NA, not analyzed; ACC, agenesis of corpus callosum; HCC, hypoplastic corpus callosum; ASD, atrial septum defect; AuSD, autism spectrum disorder; post., posteriorly; ∗, hg18; and ∗∗, occurrence of singular seizure.

The phenotype associated with nonsense and frameshift mutations in ARID1B is shown in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 1. All individuals presented with moderate to severe psychomotor retardation, and most showed evidence of muscular hypotonia. In many of the patients, expressive speech was reported to be more severely affected than receptive function. Although no distinct recognizable facial gestalt could be discerned, consistent findings in most of the patients were an abnormal head shape and low-set, posteriorly rotated, and abnormally shaped ears. Even though many other minor anomalies such as downslanting palpebral fissures, a bulbous nasal tip, a thin upper lip, minor teeth anomalies, and brachydactyly or single palmar creases were observed frequently, gross malformations such as congenital heart defects, structural brain anomalies, or cleft palate were only rarely observed. The majority of patients had short stature of postnatal onset or body height within the lower normal range. With regard to these aspects, the phenotype of patients with point mutations overlaps with that observed in patients with large genomic deletions on chromosome 6q or intragenic deletions within ARID1B12,15 (such as in patient 1), further confirming that haploinsufficiency of ARID1B is indeed responsible for most of the symptoms. However, either autism spectrum disorder or autistic traits were reported in five patients with larger genomic or intragenic deletions13,15 but were observed in only one of our patients. Three of our five patients who underwent a cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan had minor unspecific anomalies such as retrocerebellar cysts, delayed myelination, and asymmetric calvaria, but none showed a hypoplastic or aplastic corpus callosum, which was considered a hallmark of the ARID1B deficiency by Halgren et al.15 (it was only reported in patients with larger deletions there). In addition, hearing loss was also more consistently observed in patients with larger deletions12 than in our patients with point mutations in ARID1B. These two aspects might therefore be more related to the contribution of additional genes affected by chromosomal aberrations than to haploinsufficiency of ARID1B itself.

Figure 3.

Facial Appearance of Patients with Deletions or Mutations in ARID1B

Note consistently low-set, posteriorly rotated, and abnormally shaped ears and other frequent dysmorphisms such as frontal bossing, downslanting palpebral fissures, a bulbous nasal tip, and a thin upper lip.

(A and B) Patient 1 at age 3 years, 3 months.

(C and D) Patient 2 at age 4 years, 11 months.

(E and F) Patient 3 at age 3 years, 5 months.

(G) Patient 4 at age 5 months.

(H and I) Patient 4 at age 7 years, 3 months.

(J) Patient 5 at age 4 years, 11 months.

(K and L) Patient 5 at age 12 years, 8 months.

(M and N) Patient 6 at age 6 years, 3 months.

(O and P) Patient 7 at age 3 years, 10 months.

(Q and R) Patient 8 at age 17 years.

ARID1B is highly expressed in the brain and in embryonic stem cells and encodes AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1B, also known as BAF250b, the largest subunit of the mammalian SWI/SNF-A chromatin-remodeling complex. This complex facilitates DNA access with the use of transcription factors and the transcription machinery.16 BAF250b has a DNA-binding domain known as ARID (AT-rich interaction domain) and is thought to target the complex to specific genes.17 BAF250b and its ortholog BAF250a (encoded by ARID1A [MIM 603024]) associate with E2F transcription factors and play important roles in cell-cycle control.18 Recently, it has been shown that BAF250b is also part of an E3-ubiquitin-ligase complex targeting histone H2B at lysine 120 for monoubiquitination in vitro.16 Histone H2B ubiquitination has been shown to be required for transcriptional activation in vitro19 and associates with transcriptionally active genes in vivo.20,21 BAF250b interacts with Elongin B/C through its B/C box and with Cullin 2 (CUL2 [MIM 603135]) through both the ARID1B and B/C boxes and assembles the complex in a manner similar to that of the well-characterized Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) complex, which targets the hypoxia inducible factor HIF1α (MIM 603348).16

We conclude that ARID1B haploinsufficient mutations are a relatively frequent cause of moderate to severe ID, and our findings add to the growing evidence of a role of altered chromatin remodeling in the pathogenesis of ID.4,22–24

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for their cooperation. We also thank Angelika Diem, Petra Rothe, Daniela Schweizer, and Olga Zwenger for the excellent technical support. This study was supported by the German Intellectual Disability Network through a grant from the German Ministry of Education and Research to G.R., E.S., D.W., O.R., H.E., A. Rauch, and A. Reis. (01GS08160).

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP), http://www.fruitfly.org/

Human Splicing Finder (HSF), http://www.umd.be/HSF/

NetGene2 server, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetGene2/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

PANTHER 7.0, http://www.pantherdb.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

SIFT, http://sift.jcvi.org/

SpliceView, http://zeus2.itb.cnr.it/∼webgene/wwwspliceview_ex.html

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/

References

- 1.Ropers H.H. Genetics of early onset cognitive impairment. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2010;11:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarpey P.S., Smith R., Pleasance E., Whibley A., Edkins S., Hardy C., O'Meara S., Latimer C., Dicks E., Menzies A. A systematic, large-scale resequencing screen of X-chromosome coding exons in mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:535–543. doi: 10.1038/ng.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abou Jamra R., Philippe O., Raas-Rothschild A., Eck S.H., Graf E., Buchert R., Borck G., Ekici A., Brockschmidt F.F., Nöthen M.M. Adaptor protein complex 4 deficiency causes severe autosomal-recessive intellectual disability, progressive spastic paraplegia, shy character, and short stature. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Najmabadi H., Hu H., Garshasbi M., Zemojtel T., Abedini S.S., Chen W., Hosseini M., Behjati F., Haas S., Jamali P. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endele S., Rosenberger G., Geider K., Popp B., Tamer C., Stefanova I., Milh M., Kortüm F., Fritsch A., Pientka F.K. Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1021–1026. doi: 10.1038/ng.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamdan F.F., Gauthier J., Spiegelman D., Noreau A., Yang Y., Pellerin S., Dobrzeniecka S., Côté M., Perreau-Linck E., Carmant L., Synapse to Disease Group Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal nonsyndromic mental retardation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:599–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamdan F.F., Piton A., Gauthier J., Lortie A., Dubeau F., Dobrzeniecka S., Spiegelman D., Noreau A., Pellerin S., Côté M. De novo STXBP1 mutations in mental retardation and nonsyndromic epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2009;65:748–753. doi: 10.1002/ana.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zweier M., Gregor A., Zweier C., Engels H., Sticht H., Wohlleber E., Bijlsma E.K., Holder S.E., Zenker M., Rossier E., Cornelia Kraus Mutations in MEF2C from the 5q14.3q15 microdeletion syndrome region are a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and diminish MECP2 and CDKL5 expression. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:722–733. doi: 10.1002/humu.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Roak B.J., Deriziotis P., Lee C., Vives L., Schwartz J.J., Girirajan S., Karakoc E., Mackenzie A.P., Ng S.B., Baker C. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:585–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vissers L.E., de Ligt J., Gilissen C., Janssen I., Steehouwer M., de Vries P., van Lier B., Arts P., Wieskamp N., del Rosario M. A de novo paradigm for mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1109–1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauch A., Hoyer J., Guth S., Zweier C., Kraus C., Becker C., Zenker M., Hüffmeier U., Thiel C., Rüschendorf F. Diagnostic yield of various genetic approaches in patients with unexplained developmental delay or mental retardation. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:2063–2074. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagamani S.C., Erez A., Eng C., Ou Z., Chinault C., Workman L., Coldwell J., Stankiewicz P., Patel A., Lupski J.R., Cheung S.W. Interstitial deletion of 6q25.2-q25.3: A novel microdeletion syndrome associated with microcephaly, developmental delay, dysmorphic features and hearing loss. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;17:573–581. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nord A.S., Roeb W., Dickel D.E., Walsh T., Kusenda M., O'Connor K.L., Malhotra D., McCarthy S.E., Stray S.M., Taylor S.M., STAART Psychopharmacology Network Reduced transcript expression of genes affected by inherited and de novo CNVs in autism. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:727–731. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backx L., Seuntjens E., Devriendt K., Vermeesch J., Van Esch H. A balanced translocation t(6;14)(q25.3;q13.2) leading to reciprocal fusion transcripts in a patient with intellectual disability and agenesis of corpus callosum. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2011;132:135–143. doi: 10.1159/000321577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halgren C., Kjaergaard S., Bak M., Hansen C., El-Schich Z., Anderson C., Henriksen K., Hjalgrim H., Kirchhoff M., Bijlsma E. Corpus callosum abnormalities, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and autism in patients with haploinsufficiency of ARID1B. Clin. Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01755.x. Published online July 29, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X.S., Trojer P., Matsumura T., Treisman J.E., Tanese N. Mammalian SWI/SNF—a subunit BAF250/ARID1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets histone H2B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:1673–1688. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00540-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Nagl N.G., Wilsker D., Van Scoy M., Pacchione S., Yaciuk P., Dallas P.B., Moran E. Two related ARID family proteins are alternative subunits of human SWI/SNF complexes. Biochem. J. 2004;383:319–325. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagl N.G., Jr., Wang X., Patsialou A., Van Scoy M., Moran E. Distinct mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes with opposing roles in cell-cycle control. EMBO J. 2007;26:752–763. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavri R., Zhu B., Li G., Trojer P., Mandal S., Shilatifard A., Reinberg D. Histone H2B monoubiquitination functions cooperatively with FACT to regulate elongation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 2006;125:703–717. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davie J.R., Murphy L.C. Inhibition of transcription selectively reduces the level of ubiquitinated histone H2B in chromatin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;203:344–350. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minsky N., Shema E., Field Y., Schuster M., Segal E., Oren M. Monoubiquitinated H2B is associated with the transcribed region of highly expressed genes in human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:483–488. doi: 10.1038/ncb1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gécz J., Shoubridge C., Corbett M. The genetic landscape of intellectual disability arising from chromosome X. Trends Genet. 2009;25:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraft M., Cirstea I.C., Voss A.K., Thomas T., Goehring I., Sheikh B.N., Gordon L., Scott H., Smyth G.K., Ahmadian M.R. Disruption of the histone acetyltransferase MYST4 leads to a Noonan syndrome-like phenotype and hyperactivated MAPK signaling in humans and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:3479–3491. doi: 10.1172/JCI43428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer J.M., van Bokhoven H. Genetic and epigenetic defects in mental retardation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;41:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.