Abstract

The voltage-sensitive phosphatase Ci-VSP consists of an intracellular phosphatase domain (PD) coupled to a transmembrane voltage-sensor domain (VSD). Depolarization triggers the selective dephosphorylation of phosphoinositides. However, the molecular mechanisms of coupling are still elusive. To clarify the role of the VSD-PD linker as a putative partner for electrostatic interactions with the membrane, we carried out a cysteine-scanning mutagenesis of the whole motif M240-K257. Upon coexpression with PI(4,5)P2-sensitive KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels in Xenopus oocytes, we identified four positions (A242C, R245C, K252C, and Y255C) with a completely abrogated PD activity. Because the mutation effect occurred periodically, we hypothesize that α-helical elements exist within the linker, with a gap near position S249. The combination of these results with the analysis of transient sensing currents of the VSD revealed distinct roles for the N-terminal (M240-S249) and C-terminal (Q250-K257) linker motifs in the VSD-PD coupling. According to our functional results, the computational structure prediction of the Q239-D258 fragment confirmed α-helical structures within the linker, with a short β-turn around S249 in the activated conformation. Remarkably, the position K252 may be a candidate for interacting with the PD rather than for binding to the membrane. This provides the first insight (to our knowledge) into the direct intervention of the linker in the VSD-PD coupling process.

Introduction

Electrical stimulations lead to various specific cellular responses. Originally, only ion channels and transporters were believed to respond to changes in the membrane potential. The voltage-sensitive phosphatase Ci-VSP was the first protein to be described as having its catalytic activity directly controlled by the transmembrane potential (1). The molecular origin of that functionality is the modular structure of the protein, which is composed of a transmembrane voltage-sensor domain (VSD) and a cytosolic phosphatase domain (PD; Fig. 1 A). For both submodules, the individual activity has already been demonstrated (1–3).

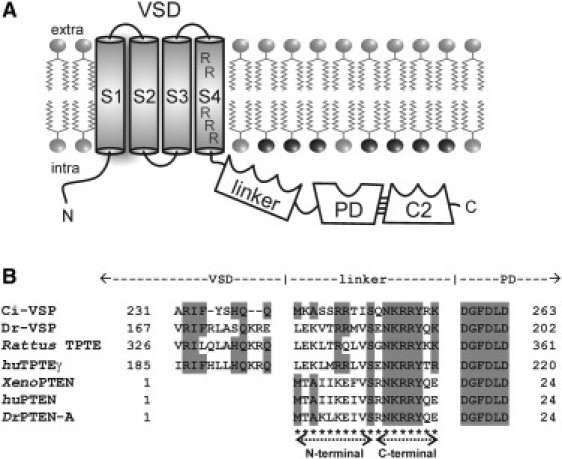

Figure 1.

(A) Topology scheme of Ci-VSP with the transmembrane VSD, the linker, which contains a PBM, the cytosolic domain comprising the PD and the C-terminal C2 domain (C2). The VSD consists of four putative α-helices, S1–S4. Arginines in S4, which are mainly responsible for the voltage sensation of the protein, are denoted. Further emphasized in black are the headgroups of the Ci-VSP substrate PI(4,5)P2. (B) Alignment between the VSD-PD-linker sequence of Ci-VSP and homologs from different species (Dr, Danio rerio; Rattus, Rattus norvegicus; hu, human; Xeno, Xenopus laevis). Amino acid identities to Ci-VSP are colored in gray. Cysteine mutations, which were generated here, are denoted with asterisks. The N- and C-terminal linker parts comprise amino acids M240-S249 and Q250-K257, respectively.

The VSD of Ci-VSP consists of four putative α-helical transmembrane segments, S1–S4. Analogously to voltage-gated ion channels, S4 contains several positively charged amino acids in the typical periodicity, and translocations of these protein-bound charges across the membrane are observable as transient sensing currents (1,4).

The conformational change of the VSD is correlated with the activity of the PD. Upon depolarization of the plasma membrane, the PD selectively dephosphorylates membranous phosphoinositides at the 5′-position of the inositol ring (5,6). This reaction has dramatic consequences because phosphoinositides are involved in diverse cellular signaling cascades (7). Of special interest in this context is the phospholipid PI(4,5)P2, which directly regulates the activity of many ion channels, such as the potassium channels GIRK2 and KCNQ2/KCNQ3 (8–10). Upon depolarization, PI(4,5)P2 levels decrease when Ci-VSP is present, causing these channels to inactivate within a few seconds (1).

But how does the signal transduction occur from the conformational change of the VSD of Ci-VSP to the activation of the PD?

For this coupling process, several groups have described the crucial role of the positively charged linker motif that contains the amino acids M240–K257 and links both protein modules (1,3,11,12). A homology analysis of Ci-VSP and its related proteins revealed a high degree of amino acid identity within this region (Fig. 1 B). These similarities persist between Ci-VSP and other transmembrane phosphatases as TPTE (13) and TPTE2 (formerly termed TPIP) (14), as well as soluble phosphatases similar to PTEN (15).

The human tumor suppressor PTEN shares ∼40% overall amino acid homology to the PD of Ci-VSP. In PTEN, the motif homologous to the linker in Ci-VSP acts as a phospholipid-binding motif (PBM) (16–18). It not only ensures the binding of the enzyme at its substrate but also seems to regulate the catalytic activity directly (19,20). Campbell et al. (16) suggested that the PBM acts in the form of a single binding site selectively for PI(4,5)P2, which requires an exact three-dimensional protein fold of that motif. In addition, Redfern et al. (18) confirmed that the whole N-terminal sequence of PTEN, including the PBM, induces conformational changes in the PD upon binding to PI(4,5)P2-containing membranes, which leads to the activation of the catalytic domain in an allosteric way. All of these results imply that for PTEN, structural changes are required in both the PD and the PBM to enable the enzymatic catalysis.

But can these considerations be transferred to the function of the Ci-VSP linker?

Several studies have shown that neutralizations of positively charged amino acids in the putative PBM of Ci-VSP impair the activity of the PD and affect the kinetics of the VSD (3,11). Kohout et al. (3) described a reduced interaction between the cytosolic domain and PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane for three neutralization mutations. The authors argued that PI(4,5)P2 stabilizes the binding of the linker at the membrane and consequently ensures the catalytic activity of the PD.

In this context, Villalba-Galea et al. (11) observed different effects on the activity of the PD when mutations of arginines in close vicinity to the S4 segment (R245/R246) were compared with those of more distally located arginines (R253/R254). Differences in the function of these N- and C-terminal linker arginines were proposed, with R253 and R254 being more crucial for binding the PBM at the membrane, and R245 and R246 suggested to stabilize this binding. Furthermore, upon simultaneous mutation of the distal arginines into lysines to maintain the electrical charges of these positions, the resulting mutant R253K/R254K showed accelerated VSD kinetics compared with the wild-type (WT) and an abrogated PD activity. This indicates that not only electrostatic conditions but also the structural properties of the PBM are essential to maintain the coupling.

However, up to now, concrete structural information about this motif has been elusive. With a detailed cysteine scanning mutagenesis of the whole linker motif M240-K257 (Fig. 1 B), we demonstrate that mutations in the N-terminal linker (M240-S249) and C-terminal linker (Q250-K257) differentially affect the relaxation kinetics of the VSD. By using various stimulation strategies and coexpression assays with the PI(4,5)P2-sensitive ion channels KCNQ2/KCNQ3, we analyzed the individual catalytic activities for all mutants. Here, we show that the C-terminal linker plays a more crucial role in preserving the activity of the PD. Furthermore, our results provide insights into the secondary structure of the linker motif.

The combination of the electrophysiological data with computational structure predictions suggests the existence of α-helical elements in the linker, which are presumably interrupted structurally around position S249 during the activation process. Furthermore, K252 was identified as a possible candidate to interact directly with the PD. With these results, we substantiate the hypothesis that in addition to the electrostatic interactions, the structural integrity of the linker is essential for the intact interaction of the Ci-VSP modules.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis

Ci-VSP cDNA was subcloned into the modified pcDNA3 vector pFROG3, which was optimized for protein expression in Xenopus oocytes (21). Ci-VSP mutations (M240C-K257C, S249A, Y255F, and K257stop) were generated with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and verified by sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany).

cRNA synthesis

Ci-VSP cDNA was linearized with KspAI (Fermentas). Afterward, cRNA was synthesized with the use of the T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 cDNA (subcloned into the plasmid vector pTLN) was linearized with NotI (Fermentas) and transcribed into cRNA with the SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Treatment of oocytes

Oocytes were obtained by partial ovariectomy from anesthetized Xenopus laevis females. After treatment with Collagenase 1A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 2–3 h, individual cells were isolated and stored at 4°C in ORI buffer (contents (in mM): 110 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 50 mg/L gentamycin. To record transient sensing currents of Ci-VSP, we injected 50 nL of 0.5 μg/μL Ci-VSP cRNA per oocyte. To measure phosphatase activity, we injected 50 nL of a KCNQ2/KCNQ3/Ci-VSP mixture (0.04:0.04:0.12 μg/μL). After injection, the oocytes were stored for 3–4 days at 18°C in ORI buffer containing 50 mg/L gentamycin.

Electrophysiology

Three to four days after injection, we recorded currents at 21–23°C with the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique using a Turbotec 10CX amplifier (NPI Instruments, Tamm, Germany). The experimental solutions were (in mM) ND96 (96 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.2 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, pH 7.4) for KCNQ2/KCNQ3-Ci-VSP coexpression measurements, and NMDG96-TEA (96 NMDG, 1 TEACl, 1 MgCl2, 0.2 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, 18 HCl, 80 glutamic-acid, pH 7.4) to monitor transient sensing currents. To record transient sensing currents, we used voltage-step protocols starting from a holding potential of −60 mV, followed by steps to various test potentials between −40 and +140 or +160 mV (increment 20 mV, duration 500 ms, interpulse holding time 1 min). VSD off-currents were measured by stepping back to −50 mV after the test potential phase. For kinetic analyses, the duration of the off-pulse was 500 ms. Linear leak and capacitative currents were subtracted by using the P/x-compensation method (1) with x = −4 and a subsweep holding level of −60 mV. Signals of sensing currents were filtered at 3 kHz and sampled with 10 kHz. For ionic currents of KCNQ2/KCNQ3, we measured signals by stepping from a holding potential of −60 mV to various test potentials between −100 and +160 mV at maximum (increment 20 mV, duration 1 s, interpulse holding time 1 min), followed by a tail pulse at −30 mV. From these signals, the initial current amplitude during the tail pulse was determined and normalized to the value corresponding to the test potential at 0 mV. Signals of ionic currents were filtered at 1 kHz and sampled with 2 kHz. To determine τ10% and τ50% during long-lasting depolarization, signals were monitored from a holding potential of −80 mV (filtered at 200 Hz, sampled with 500 Hz). As shown in Fig. 2A, stimulation potentials to +80 mV or more positive values were applied for an expanded time period. Stimulations were repeated after a recovery phase of 1–2 min at −80 mV.

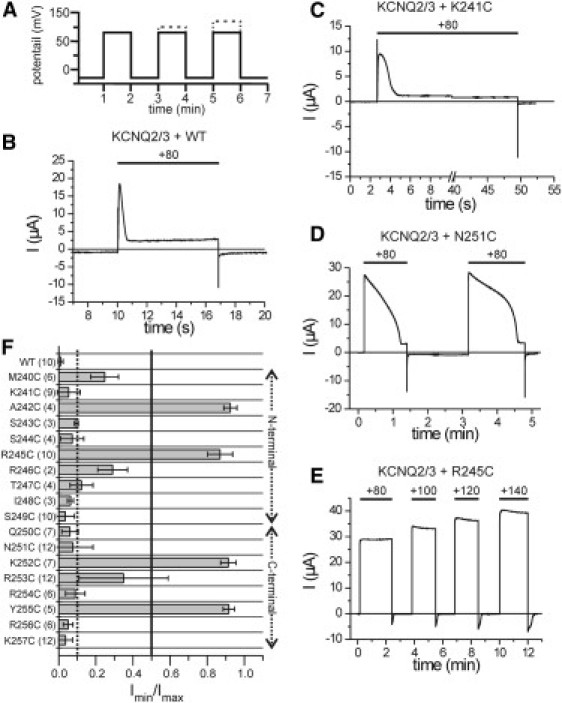

Figure 2.

Individual phosphatase activities of all cysteine mutants were determined in coexpression with KCNQ2/KCNQ3 by long-lasting voltage pulses. (A) Voltage protocol of the stimulation strategy. From a holding potential of −80 mV, a test pulse to +80 mV was applied for an extended time period. In the case of no inhibitory activity on the KCNQ-channels at +80 mV, the stimulation voltage was increased up to +120 or +140 mV. (B–E) Representative current traces are shown for the Ci-VSP WT and several mutants, as indicated. (F) Quantitative analysis of the current responses of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 during the long-lasting depolarization. In coexpression with Ci-VSP constructs, the minimal current amplitude (Imin) was determined from the steady-state current during the first stimulation phase at +80 mV. Imin was normalized to the maximal peak current amplitude during the initial phase of the potential step (Imax). Thresholds for a current decrease to 10% and 50% are shown as dotted and straight lines, respectively. Corresponding time durations (τ10% and τ50%) are listed in Table S1.

Data acquisition and analysis

Currents were acquired with the use of pClamp 10 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Data were analyzed with pClampfit 10 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 7.0 (Microcal, Northampton, MA). The time constants τoff for the VSD off-currents were determined by exponential approximation:

| (1) |

with N = 1 for monoexponential and N = 2 for biexponential kinetics.

According to Eq. 1, we used a data set for the fitting session that started from t = 5 ms to calculate the initial current amplitudes at the onset of the off-pulse directly from the fitted function, and to eliminate residual capacitive artifacts. The charge that translocated during the VSD off-motion, Qoff, was determined from the fitting parameters from Eq. 1 with:

| (2) |

Qoff,fast was calculated from the product of τoff,fast and its corresponding initial current amplitude Ioff,fast. Qoff,slow was determined analogously with the values of τoff,slow and Ioff,slow.

We determined the values that described the voltage dependence of the VSD off-kinetics, V0.5 and zq, by fitting the Qoff-V relationship with a Boltzmann-type function:

| (3) |

where F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin.

For statistics, at least three independent measurements were analyzed. Oocytes were obtained from at least two different cell batches. Unless otherwise mentioned, means±standard deviations are presented.

Structure prediction

We predicted the secondary structure of the linker motif M240-K257 by using the Robetta server (22). By including the two neighboring residues (Q239 and D258), we obtained a 20-amino-acid-long sequence for the modeling. Because up to now detailed structural information about the linker has been lacking, we carried out a de novo prediction, implemented in Robetta. The prediction was independently performed twice. Each procedure provided five individual structure models. We compared these single structures by evaluating the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the backbone atoms using the visual molecular-dynamics software VMD 1.8.7 (23). We identified two models out of five as being reproducible and energetically most favorable. Both structure models were in agreement with results obtained by the secondary structure prediction tools PsiPred (24) and SAM (25,26).

Results

PD activity is differentially affected by N- and C-terminal linker mutations

To further understand the role played by the linker region in the coupling between the Ci-VSP modules, we carried out a cysteine scanning mutagenesis of the whole motif M240-K257. In similarity to previous studies, we heterologously coexpressed the cysteine mutants of Ci-VSP with the PI(4,5)P2-sensitive ion channels KCNQ2/KCNQ3 in Xenopus oocytes.

First, we recorded the current response of the ion channels to variable short-period potential pulses (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). Under these conditions, almost all mutants of the N-terminal linker region (M240C-S249C) were able to inhibit the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 currents similarly to WT Ci-VSP (Fig. S1, C and D), except for A242C and R245C, which had no effect on the channel currents (Fig. S1 E). In contrast, all mutations in the C-terminal linker, with the exception of Q250C and K257C, seemed to abrogate the PD activity completely (Fig. S1, F and G). However, for one C-terminal mutant, R256C, a slight reduction of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 currents was observable under these stimulation conditions (Fig. S1, B and G), which led us to assume that the duration of the voltage pulses was not long enough to elicit the PI(4,5)P2-depletion activities of the cysteine mutants reliably. Therefore, we prolonged the duration of the stimulation pulses as shown in Fig. 2 A.

We quantified the corresponding currents by determining the minimal steady-state current amplitude of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels during the first stimulation period. This value was normalized to the maximal current amplitude during the initial phase of the depolarization pulse to determine the extent of inhibition for every mutant (Fig. 2 F). Furthermore, we determined the time that was needed to reduce the channel currents to 50% and 10% of the initial maximal amplitude (see Table S1).

In contrast to the short stimulation assay, here only four mutants (A242C, R245C, K252C, and Y255C) showed a completely abrogated PI(4,5)P2-depletion activity (Fig. 2 F) even upon a further increase of the stimulation potential to +140 mV (Fig. 2 E, Fig. S2). Remarkably, several mutations within the C-terminal part of the linker dramatically slowed down the decay of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 currents (e.g., N251C; Fig. 2 D, Table S1). These results suggest that mutations in the C-terminal linker are more destructive to Ci-VSP function compared with mutations in the N-terminal region.

Structural information about the linker based on different PD activities

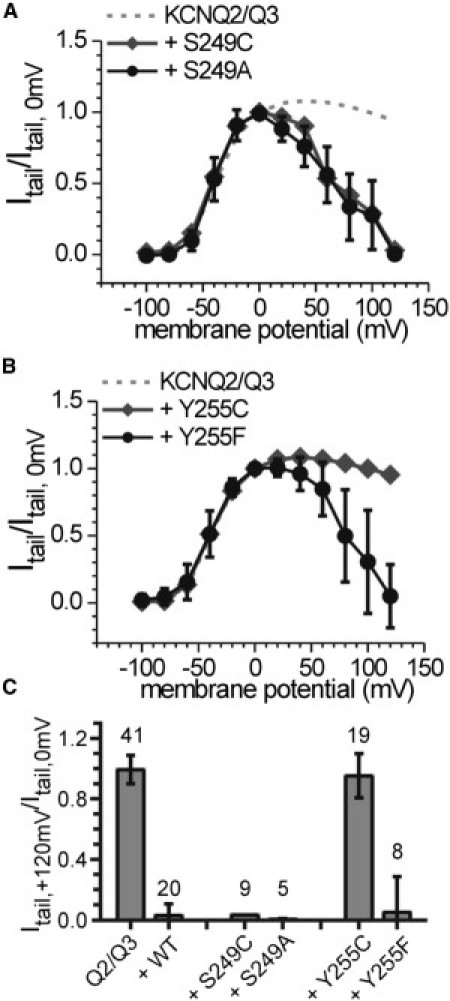

The sequence of inactivating linker mutations (A242C and R245C, and K252C and Y255C; Fig. 2F) evinces a three-amino acid periodicity, which is a characteristic feature of α-helical structures in proteins. However, this α-helical pattern exhibits a gap at the center of the linker near residues I248 and S249. A comparison of the native amino acids with the introduced cysteine suggests that the S249C substitution would have less impact on the activity, because of the sterical and hydrophobic similarities between serine and cysteine. To further elucidate the role of the serine side chain, we mutated S249 into alanine. As shown in Fig. 3, A and C, the S249A mutant also inhibits the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 currents as efficiently as the WT.

Figure 3.

Tail currents recorded from oocytes coexpressing KCNQ2/KCNQ3 with the Ci-VSP mutants (A) S249A and (B) Y255F (black circles and lines, respectively) normalized to the tail-current amplitude observed after a test potential of 0 mV. Results of the corresponding cysteine mutants (S249C and Y255C) are inserted as well as the signals that were received when KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels were expressed alone. (C) Summary of normalized tail currents at +120 mV (numbers of experiments are indicated).

In addition, I248C shows an impaired but not completely abrogated PD activity (Fig. S1 G, Fig. 2 F), although this substitution mutation should have more dramatic consequences for the structural integrity of the linker at this position. For mutations in the region I248C to Q250C, the enzymatic activities are not severely reduced (Fig. S1 G, Fig. 2 F). It seems that this region is less important for the VSD-PD interaction, because mutations of that sequence do not dramatically alter the functionality of the protein. Additionally, at position S249, small amino acids seem to be tolerated well. Given this structural information, it is conceivable that a certain degree of flexibility is mediated around this position, which might enable different functionalities for the N- and C-terminal regions of the linker.

Furthermore, besides R245 and K252, two hydrophobic residues, A242 and Y255, were identified to be crucial for maintaining the activity of the PD. This finding supports the previous assumption that not only the electrostatic conditions but also the structural integrity of the linker is important for the VSD-PD coupling (11,12). To determine the functional role of these hydrophobic residues, we tested the importance of the hydroxyl group of the tyrosine, which may act as a partner for hydrogen bonds, by analyzing the substitution mutant Y255F. Interestingly, the Y255F mutant inhibits the KCNQ2/KCNQ3-channel currents similarly to Ci-VSP WT (Fig. 3, B and C). Thus, the phenyl ring itself, and not the hydroxyl group, seems to be important for the intact function of the linker.

Taken together, these results confirm the notion that, in addition to the electrostatic properties, the structural integrity of the linker is essential for maintaining the VSD-PD interaction.

Recording conditions to analyze the VSD off-currents on a Ci-VSP WT background

In addition to the PD activity analyses, we also wanted to investigate the effect of linker mutations on the VSD kinetics. Previous studies that addressed this issue were based on the catalytically inactive mutant C363S (4,11), because data suggested that the interaction of the PBM with the Ci-VSP substrate PI(4,5)P2 influences the conformational changes of the VSD directly (3).

However, the use of C363S as background for analyzing transient sensing currents requires careful consideration. It should be noted that for PTEN, it is presumed that the homologous mutation C124S increases the membrane binding of the protein in comparison with the WT (20). Initially, this effect was believed to be due to the inactivity of the mutant against phosphoinositides, because a lack of depletion could entail an unconstrained binding to these lipids. However, other mutations of PTEN that also render the phosphatase inactive (i.e., G129R and D92A) did not show this binding enhancement (27). It is conceivable that the C124S substitution at the active site of the PD creates conditions in which the substrate-binding pocket gets trapped at the membrane during the catalytic cycle and hence causes the increase in binding of the whole cytosolic domain.

Similarly, for Ci-VSP, it also could be possible that the inactivating mutation C363S induces an enhanced binding behavior of the PD to the membrane, which may affect the VSD kinetics. This hypothesis is supported by Kohout et al. (3), who demonstrated that C363S indeed alters the return of the VSD gating charges after depolarization. In agreement with these results, we also observed differences in the VSD off-kinetics between C363S and the WT (Fig. S3).

Because the effects caused by C363S could interfere with those of the linker mutants, we used WT Ci-VSP as background for our kinetic analyzes. A caveat of this experiment is that the PI(4,5)P2-depletion activity of the WT may induce an acceleration of the VSD off-motion, because PI(4,5)P2 itself is known to stabilize the binding of the PBM at the membrane (3), which subsequently might cause a slow-down of the VSD off-currents. Therefore, we ensured a recovery of the PI(4,5)P2 concentration at the membrane after a depolarization pulse by using the following strategy: In coexpression with the WT, the current amplitude of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels regenerates between repeatedly applied depolarization pulses when the cell is hyperpolarized to keep the PD of Ci-VSP inactive (Fig. S4). Because the ionic currents are completely regenerated within 1 min at a subpulse holding potential of −60 mV (Fig. S4 H), we assumed that these conditions would be sufficient to restore the effective PI(4,5)P2 concentration at the membrane to the level observed before the first stimulation pulse was applied. Therefore, we obtained all recordings of VSD kinetics in response to voltage steps by holding individual cells for 1 min at a recovery potential of −60 mV between pairs of test pulses.

Insights into the membrane-binding processes of the cytosolic domain by VSD dynamics

Under the conditions described above, we first analyzed the VSD dynamics of the Ci-VSP WT (Fig. 4). We quantified the off-currents of the VSD, which occur upon return from the variable test potentials to a constant off-pulse at −50 mV.

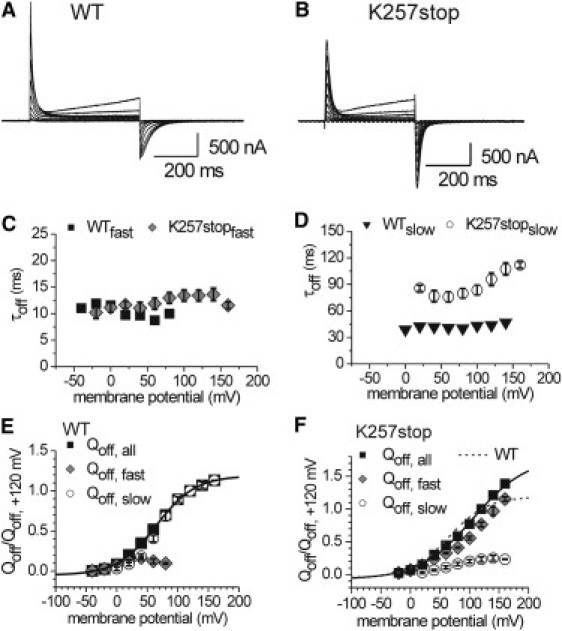

Figure 4.

Transient sensing currents recorded from oocytes expressing (A) Ci-VSP WT and (B) the mutant K257stop in response to variable test potentials between −40 and +160 mV. Off-currents were obtained by stepping back from the test potential to −50 mV as result of the inward motion of the VSD. (C and D) Time constants for the off-kinetics (τoff) were determined by exponential approximation of the VSD off-currents. Represented are the (C) fast and (D) slow τoff-values for the WT and K257stop. (E and F) Voltage-dependent Qoff distributions were determined as described in Materials and Methods, and are presented for the (E) WT and (F) K257stop. Plotted are the fast (Qoff,fast) and slow (Qoff,slow) Qoff fractions, as well as the sum of both (Qoff,all). Qoff,all was approximated by a Boltzmann-type function. Fitting parameters V0.5 and zq are listed in Table S2.

After test potentials of −40 and −20 mV, the off-currents of the WT are small because the potential differences of the repolarization steps are small and probably cause only limited translocations of sensing charges (Fig. 4 E). Furthermore, in this potential range, the VSD off-currents occur rapidly and monoexponentially (Fig. 4, C and E). Between 0 and +80 mV, the off-kinetics are more complex and comprise two exponential components. The analyses of the amount of translocated gating charge (Qoff; Fig. 4 E) revealed that the fast and slow Qoff fractions contribute almost equally to the VSD off-kinetics between 0 and +40 mV, whereas at more positive potentials the off-currents are dominated by the slow fraction. Above +80 mV, the slow component defines the off-kinetics completely.

What could the slow Qoff fraction mean on a molecular level? Previous studies demonstrated that during long depolarization pulses, the VSD goes into a relaxed state (4,28), which results in a retardation of the transition into the resting state at hyperpolarization. In the light of these results, we cannot exclude the possibility that the VSD undergoes conformational changes upon our depolarizing stimulation, causing the off-kinetics to be slowed down. However, for the WT, the occurrence of the slow Qoff fraction correlates with the enzymatic activity of the PD (Fig. S1 C). Therefore, we assume that the slow Qoff component of the VSD kinetics is associated with the dissociation of bound cytosolic parts of the protein from the membrane. Furthermore, we suggest that the more Qoff,slow was delayed, the more efficiently was the PD bound during the test potential phase. In particular, we presume that this membrane binding of the PD is one of the most crucial steps in enabling the enzymatic catalysis.

To discriminate this process from putative intrinsic conformational changes of the VSD, we created the mutant K257stop, which lacks the cytosolic domain from position D258 onward and only comprises the entire N-terminal VSD and linker motif. As the WT, this mutant was able to generate robust sensing currents (Fig. 4 B). The Qoff-V distribution of the off-currents is composed of two distinct fractions for potentials above 0 mV (Fig. 4 F). Interestingly, the slow time constant shows a significant voltage dependence (Fig. 4 D), which is presumably associated with intrinsic conformational changes of the VSD or binding events mediated by the PBM. However, the slow Qoff-fraction remains almost constant over the whole potential range, whereas the fast Qoff-fraction dominates the off-kinetics of K257stop the more the membrane is depolarized (Fig. 4 F). These results confirm our hypothesis that the dominating slow Qoff fraction observed for the WT is associated primarily with binding processes caused by the cytosolic domain of the protein, and only slightly by the VSD itself.

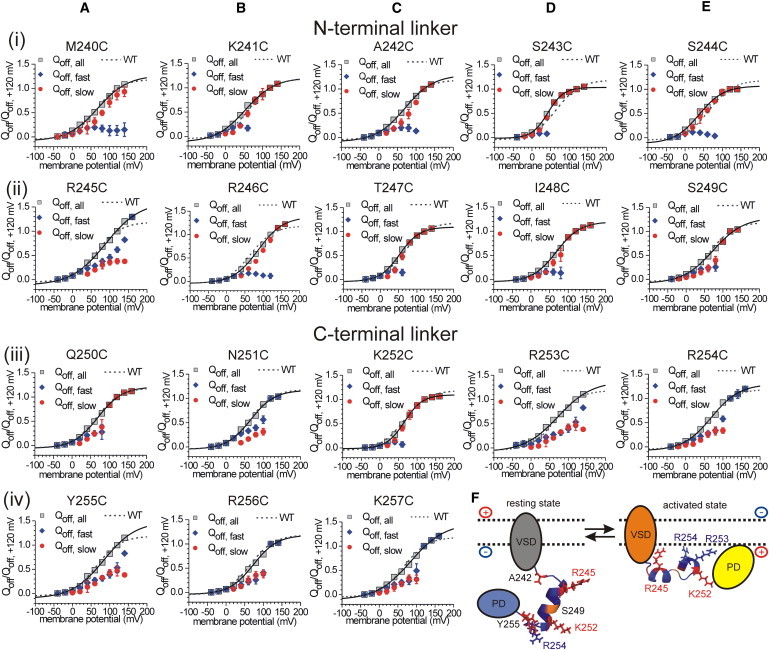

The N- and C-terminal linker parts differ in their VSD off-kinetics

We further analyzed the effects of the cysteine linker mutations on the VSD off-kinetics. For all mutants except K252C (see below), we observed a different kinetic behavior compared with the WT (Fig. 5, Fig. S5, and Fig. S6). In some cases, these changes are combined with a change in the voltage dependence of the Qoff-V distribution. For example, the VSD off-kinetics of several mutants comprises two Qoff-fractions over the whole potential range (e.g., M240C and R253C; Fig. 5), which is correlated with a reduced enzymatic activity (Fig. 2 F). Furthermore, the mutations S243C and S244C lead to a significant negative shift and an increase in slope of the Qoff-V distribution (Fig. 5, Table S2). Of note, only in the case of S243C is the voltage-dependent catalytic activity also negatively shifted compared with the WT (Fig. S1 D), which may be due to an enhanced VSD-PD interaction for this mutant.

Figure 5.

(A–E) Voltage dependence of translocated sensing charges (Qoff) obtained from the VSD off-currents after a test potential phase between -40 and +160 mV. Plotted are the fast (Qoff,fast) and slow (Qoff,slow) fractions of the Qoff-V distribution, and the sum of both (Qoff,all). Individual Qoff-values obtained per oocyte were normalized to the respective Qoff,all-value at +120 mV. Results are subdivided into N-terminal (line i-ii) and C-terminal (line iii-iv) linker mutants. For comparison, the Qoff,all-V distribution of the WT is plotted as a dotted line. (F) Secondary structure of the linker motif as predicted by the Robetta server (see Materials and Methods). The two most favorable structure models are represented as a long α-helix of 11 amino acids (S244–R254, left), and an α-helical conformation from S243 to K257 interrupted by the short sequence S249–N251, which adopts a β-turn (right). Color code: red, positions that have an abrogated PD activity upon substitution against cysteine (A242, R245, K252, and Y255); orange, the backbone of S249; blue, the backbone of all other linker positions. Arginines R253 and R254 are indicated as sticks.

In addition, all of the linker mutants (except for K252C) with a reduced or an abrogated enzymatic activity (e.g., R245C, N251C, and Y255C) consistently exhibited a pronounced fast Qoff fraction in their VSD off-kinetics (Figs. 2 F and 5). In the case of A242C, the Qoff-V distribution is dominated by the slow fraction; however, the slow time constant is significantly faster compared with the WT at potentials above +60 mV (Fig. S6).

Taken together, the kinetic data are consistent with the results obtained from the analysis of the PD activities. Even though the kinetic data alone do not provide further detailed information about the suggested α-helical character of the linker region, these results demonstrate that mutation of a single amino acid in the linker alters the off-motion of the VSD, which emphasizes the importance of the whole linker motif for the VSD-PD interaction.

Of special interest in this context are the differences between the fast and slow Qoff fractions for the N- and C-terminal linker regions. Whereas the slow Qoff fraction dominates the kinetics for most of the N-terminal mutants, the off-currents of the C-terminal mutants are largely determined by the fast component (except for Q250C and K252C; Fig. 5). Furthermore, the C-terminal Qoff-V distributions resemble the results obtained with the K257stop mutant. Therefore, our results strongly suggest that mutations in the C-terminal linker interfere more severely with the binding of cytosolic parts of the protein to the membrane than the mutations in the N-terminal region.

Differences in the VSD kinetics of K252C indicate a special role of this position in coupling

Of note, K252C is the only exception for the correlation between the reduced PD activity and accelerated VSD kinetics. Kohout et al. (3) previously demonstrated that the mutation of K252 into glutamine impairs the PD activity. In accord with these results, in our study the substitution K252C abrogated the PD activity completely (Fig. S2 B). However, in terms of the VSD off-kinetics, K252C behaves differently compared with the other inactive mutants (A242C, R245C, and Y255C; Fig. S5 and Fig. S6). Furthermore, the VSD off-kinetics of K252C is similar to that of the WT, with a dominating slow Qoff fraction at more positive potentials (Fig. 5 C, line iii), which suggests that the membrane binding of the cytosolic domain is not affected by the mutation.

These results led us to speculate that binding of the PD alone is not sufficient to initiate or pass through the whole catalytic cycle. This hypothesis is supported by the kinetic results of C363S (Fig. S3). This mutation directly affects the active site of the protein and abolishes the enzymatic activity. However, the mutation obviously does not cause a reduced membrane binding, because the slow Qoff fraction dominates the VSD off-kinetics similarly to or even more so compared with the WT (Fig. S3, F and G).

Given the results obtained for C363S and K252C, it is conceivable that the active site of the protein has to be positioned correctly during the binding of the PD at the membrane and also during the catalytic cycle. Whereas C363S presumably interferes with catalysis, K252C seems to directly affect processes that are crucial for positioning the active site without impairing the membrane binding of the cytosolic domain per se.

Discussion

The Ci-VSP molecule is composed of two different submodules: a transmembrane VSD and a cytosolic PD. This modular structure enables the voltage-dependent activity of the protein, which was identified as dephosphorylation of phosphoinositides upon depolarization of the plasma membrane (5,6,29). It was previously demonstrated that both submodules are able to function independently (1–3). Moreover, Alabi et al. (30) transferred parts of the VSD from Ci-VSP to voltage-gated potassium channels without disrupting the ion channel function. Quite recently, Lacroix et al. (12) were able to generate PTEN-/Ci-VSP chimera by substituting the whole cytosolic domain of Ci-VSP with the homologous domain of PTEN. Interestingly, the resulting artificial phosphatases had the substrate specificity of PTEN and a voltage-dependent PD activity similar to Ci-VSP. Taken together, these results emphasize the extensive range of possible applications of the Ci-VSP modularity.

Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms of the intermodular coupling in Ci-VSP are still not fully understood. In this context, the role of the region that links the VSD with the PD (M240-K257) has been particularly debated in recent years (3,11,12,31). For PTEN, the N-terminal motif, which is homologous to the Ci-VSP linker (Fig. 1 B), is generally accepted to act as a PBM (16–19). This proposed functionality is based on the positively charged character of the PBM, which enables electrostatic interactions with negatively charged membrane surfaces. It is assumed that the binding of the PBM at the membrane initiates the recruitment of the PD to its membranous substrate, which leads to activation of the catalytic cycle (16–20).

Previous studies demonstrated that the Ci-VSP linker also acts as a PBM, because it comprises several positively charged amino acids that presumably interact with membrane surfaces via electrostatic interactions (3,11,31). However, Villalba-Galea et al. (11) proposed that maintaining the electrostatic properties in the linker is not sufficient to maintain the proper function of the PBM. They found that the simultaneous mutation of pairs of C-terminal arginines into lysines (R253K/R254K) abrogated the PD activity and accelerated the VSD off-kinetics in comparison with the WT, even though the positive charges of these linker positions remained (11).

Our work shows that mutations of the two hydrophobic positions, A242 and Y255, into cysteines abrogated the PD activity completely. For Y255, substitution of tyrosine to phenylalanine maintained the catalytic activity, which demonstrates the importance of the phenyl ring at this position. These results confirm the notion that, in addition to its electrostatic properties, the structural integrity of the linker is crucial for its functionality.

Furthermore, our data provide several informations about the putative secondary structure of this motif. The periodicity of the effect on the PD activity by the cysteine mutations indicates an α-helical pattern for the N- and C-terminal linker regions, with a structural gap around position S249. Based on the differences for the N- and C-terminal linker parts in the PD activities, as well as in the VSD off-kinetics, we assume that both regions differently affect the coupling process. But what do these differences mean in terms of function?

For PTEN, it has been suggested that its N-terminal motif, which is homologous to the Ci-VSP linker, might act as a direct regulator of the catalytic cycle (16,19,20). Iijima et al. (19) revealed that a deletion of the motif changes the substrate specificity of the PD against soluble phosphoinositides, which indicates a direct influence of this region on catalysis, possibly by occlusion of the active site in the resting state.

In the case of Ci-VSP, Kohout et al. (3) demonstrated that the PD, which lacks the VSD and the linker, completely loses its catalytic activity against both membrane-bound and soluble substrates. Although these results differ from those obtained for PTEN, they suggest an active role for the linker in phospholipid catalysis, because its presence seems to be crucial for keeping the PD active. Additionally, Lacroix et al.'s (12) study of PTEN-/Ci-VSP chimera revealed that the portability of a functional PD from PTEN to Ci-VSP strongly depends on the sequence of the linker. Based on these results, the authors proposed that the linker has to match its PD to maintain the coupling. Furthermore, they proposed that the motif may act as an adaptor for binding between the membrane and the PD.

In line with this hypothesis, our results suggest that K252 in the C-terminal linker may interact directly with the PD. To accomplish such a direct interaction, K252 would have to be oriented away from the negatively charged membrane surface into the direction of the PD. Unfortunately, our experimental data alone do not prove this hypothesis satisfactorily, and the published crystal structures of the cytosolic domain of Ci-VSP (32) and of PTEN (33) do not comprise the N-terminal linker region. Hence, there is no well-defined starting point for structurally guided mutagenesis approaches to identify which amino acids in the PD could potentially interact with K252.

To overcome this lack of information, we carried out computational modeling of the linker structure using the Robetta server (see Materials and Methods). Fig. 5 F shows the two favored structural predictions indicating that the linker can adopt two different conformations. The first one consists of a long α-helix ranging from S244 to R254 (Fig. 5 F, left), in which the hydrophobic residues A242 and Y255 seem to stabilize the boundaries of the helix. The second structure exhibits a helix break around S249 by adopting a short β-turn (Fig. 5 F, right). The conformational change between these two structures may lead to the separation of the two helical linker regions that is predicted to occur during the activation process. In this model, the N-terminal residue R245 presumably initiates the binding of the linker to the negatively charged membrane surface. Afterward, the C-terminal arginines R253 and R254 follow and bind at the membrane, enabled by the structural break within the linker. These binding events may result in the recruitment of the cytosolic domain to the membrane, whereby K252 is reoriented into the direction of the PD. In this way, the interactions between K252 and residues inside the PD could be facilitated, ultimately leading to the coordination of the active site and activation of the catalytic cycle.

With this model, it is possible to explain our data consistently. If the binding of the C-terminal linker, and primarily of R253 and R254, were crucial for the subsequent recruitment of the PD to the membrane, mutations of the respective linker positions would interfere with both the binding of the C-terminal linker and the recruitment of the PD. This explains the differences observed in the VSD off-kinetics for the N- and C-terminal linker mutants.

Furthermore, assuming that interactions between K252 and the PD have to be formed to initiate the catalytic cycle, it is probable that mutations in close vicinity of K252 would slow down the formation of these interactions. These considerations would explain the significantly delayed PD activities of the C-terminal linker mutants, especially of N251C and R253C (Fig. 2 F, Table S1).

Lastly, if R245 were responsible for initiating the membrane binding of the N-terminal linker, the subsequent structural break around position S249, and the binding of the C-terminal linker and subsequently of the PD, it would be logical to conclude that the R245C mutation abrogates the whole activation process. Consequently, in the R245C mutant, the PD is neither recruited to the membrane (as highlighted by the fast VSD off-currents) nor activated (as indicated by the complete loss of PI(4,5)P2-depletion activity).

Although the hypothesized processes are compatible with our experimental results and structural predictions, we are aware that further structural and mutagenesis work is required to shed light on the conformational dynamics of Ci-VSP and to identify putative binding partners of K252 within the PD. However, the results of this study provide important insights into the coupling process on a molecular level, and especially highlight the differential role of the N- and C-terminal linker parts.

Conclusion

The motif M240-K257, which links the voltage sensor and the PD in Ci-VSP, seems to be more than a partner for the electrostatic binding to the plasma membrane. Its structural integrity is presumably important for four different molecular mechanisms, which we suggest are equally crucial for the linker-mediated coupling: 1), stabilizing the whole motif in a self-contained structure through its hydrophobicity (A242 and Y255); 2), enabling structural changes of the sequence during the activation process through its spatio-sterical properties (S249); 3), binding to the plasma membrane through electrostatic interactions (R245, R253, and R254); and 4), providing electrostatic interactions between the linker with the PD (K252), which transfers the conformational change from the VSD directly to the PD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Yoshimichi Murata for providing the Ci-VSP cDNA, Ina Seuffert for excellent technical assistance, Susan Spiller (née Meier) and Karen Mruk for critical readings of the manuscript, and all members of the T. Friedrich laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was funded by grants from the Cluster of Excellence Unifying Concepts in Catalysis, and the Berlin International Graduate School of Natural Science and Engineering (scholarship for K.H.), both launched by the German federal and state governments.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Murata Y., Iwasaki H., Okamura Y. Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature. 2005;435:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature03650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundby A., Mutoh H., Knöpfel T. Engineering of a genetically encodable fluorescent voltage sensor exploiting fast Ci-VSP voltage-sensing movements. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohout S.C., Bell S.C., Isacoff E.Y. Electrochemical coupling in the voltage-dependent phosphatase Ci-VSP. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villalba-Galea C.A., Sandtner W., Bezanilla F. S4-based voltage sensors have three major conformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17600–17607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807387105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki H., Murata Y., Okamura Y. A voltage-sensing phosphatase, Ci-VSP, which shares sequence identity with PTEN, dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7970–7975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803936105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halaszovich C.R., Schreiber D.N., Oliver D. Ci-VSP is a depolarization-activated phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate 5′-phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:2106–2113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803543200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suh B.-C., Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C.L., Feng S., Hilgemann D.W. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature. 1998;391:803–806. doi: 10.1038/35882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H., He C., Logothetis D.E. Activation of inwardly rectifying K+ channels by distinct PtdIns(4,5)P2 interactions. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:183–188. doi: 10.1038/11103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Gamper N., Shapiro M.S. Regulation of Kv7 (KCNQ) K+ channel open probability by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9825–9835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2597-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villalba-Galea C.A., Miceli F., Bezanilla F. Coupling between the voltage-sensing and phosphatase domains of Ci-VSP. J. Gen. Physiol. 2009;134:5–14. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacroix J., Halaszovich C.R., Villalba-Galea C.A. Controlling the activity of a phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) by membrane potential. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:17945–17953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tapparel C., Reymond A., Antonarakis S.E. The TPTE gene family: cellular expression, subcellular localization and alternative splicing. Gene. 2003;323:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker S.M., Downes C.P., Leslie N.R. TPIP: a novel phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase. Biochem. J. 2001;360:277–283. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Yen C., Parsons R. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell R.B., Liu F., Ross A.H. Allosteric activation of PTEN phosphatase by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33617–33620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker S.M., Leslie N.R., Downes C.P. The tumour-suppressor function of PTEN requires an N-terminal lipid-binding motif. Biochem. J. 2004;379:301–307. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redfern R.E., Redfern D., Gericke A. PTEN phosphatase selectively binds phosphoinositides and undergoes structural changes. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2162–2171. doi: 10.1021/bi702114w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iijima M., Huang Y.E., Devreotes P.N. Novel mechanism of PTEN regulation by its phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding motif is critical for chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16606–16613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vazquez F., Devreotes P. Regulation of PTEN function as a PIP3 gatekeeper through membrane interaction. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1523–1527. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.14.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenderink J.B., Zifarelli G., Friedrich T. Na,K-ATPase mutations in familial hemiplegic migraine lead to functional inactivation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1669:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim D.E., Chivian D., Baker D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh468. W526-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14 doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 33–8, 27–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones D.T. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karplus K., Barrett C., Hughey R. Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:846–856. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park J., Karplus K., Chothia C. Sequence comparisons using multiple sequences detect three times as many remote homologues as pairwise methods. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:1201–1210. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vazquez F., Matsuoka S., Devreotes P.N. Tumor suppressor PTEN acts through dynamic interaction with the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3633–3638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510570103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villalba-Galea C.A., Sandtner W., Bezanilla F. Charge movement of a voltage-sensitive fluorescent protein. Biophys. J. 2009;96:L19–L21. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murata Y., Okamura Y. Depolarization activates the phosphoinositide phosphatase Ci-VSP, as detected in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing sensors of PIP2. J. Physiol. 2007;583:875–889. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alabi A.A., Bahamonde M.I., Swartz K.J. Portability of paddle motif function and pharmacology in voltage sensors. Nature. 2007;450:370–375. doi: 10.1038/nature06266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamura Y. Another story of arginines in voltage sensing: the role of phosphoinositides in coupling voltage sensing to enzyme activity. J. Gen. Physiol. 2009;134:1–4. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda M., Takeshita K., Nakagawa A. Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-like region of Ciona intestinalis voltage-sensing phosphatase provides insight into substrate specificity and redox regulation of the phosphoinositide phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23368–23377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J.O., Yang H., Pavletich N.P. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell. 1999;99:323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.