Abstract

Dysfunctional basal ganglia loops are thought to underlie the clinical picture of Tourette syndrome (TS). By altering dopaminergic activity in the affected neural structures, bilateral deep brain stimulation is assumed to have a modulatory effect on dopamine transmission resulting in an amelioration of tics. While the majority of published case reports deals with the application of bilateral stimulation, the present study aims at informing about the high effectiveness of unilateral stimulation of pallidal and nigral thalamic territories in TS. Potential implications and gains of the unilateral approach are discussed.

Keywords: deep brain stimulation, motor-loop activity, thalamus, Tourette syndrome, unilateral stimulation

Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neuropsychiatric disorder with childhood onset that manifests itself in motor and phonic tics. Both, tic frequency and severity usually increase during childhood and peak during pre-pubescent years but decline as patients enter adulthood. Hence, more than one-third of the affected individuals become symptom-free and another third at least achieves substantial remission by the age of 18. However, in a fraction of patients, tics do not dissolve and are unresponsive to conventional behavioral or pharmacological treatments.1

In 1999, deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been introduced as a treatment option for otherwise treatment refractory TS2 after it had been proven to be effective in reducing the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease (PD). Since then, research has indicated that stimulation of various neural targets, including different thalamic3, 4 pallidal5, 6 and limbic structures,7 is able to promote an amelioration of TS symptoms. Most published cases, however, describe the effects of bilateral stimulation. The need to quantify the efficiency of bilateral and unilateral stimulation in PD has just recently been addressed in the frame of the National Institutes of Health COMPARE cohort.8 However, there is hardly any literature describing the effects of unilateral stimulation in TS.

Therefore, the present report aims to contribute to the establishment of a well-grounded database by informing about the clinical outcome of two TS patients who have received only unilateral thalamic stimulation.

Materials

As previous behavioral and medical treatment did not yield an essential amelioration of symptoms, DBS was administered to both patients in an individual treatment attempt. The decision to administer DBS to both patients was furthermore guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria for DBS in TS formulated by Mink et al.9 To scientifically document the course of the Tourette syndrome after surgery, patients were included into ongoing research projects (KFO-219 and ELSA-DBS, see also acknowledgements), carried out at our site. Approval for the projects had been obtained by the ethics committee of the University Hospital Cologne. Although the projects include roughly half a dozen patients, the present report is limited to two TS patients whose tics were not only but predominantly one-sided and who have therefore received only contralateral thalamic stimulation.

Surgery

Surgery was performed under a local anesthetic to allow intraoperative test stimulation. A detailed description of the surgical procedure was published elsewhere.7 Stereotactic planning of the electrode trajectory was based on Hassler's10 classification of the thalamus, thereby targeting the nucleus ventrooralis posterior (VOP), and the ventrooralis anterior and the ventrooralis internus complex. According to more recent thalamic classification systems like those of Mai11 or Ilinsky and Kultas-Ilinsky12 the electrode planning aimed at targeting the ventral anterior (VA) nucleus and the ventrolateral (VL) nucleus of the thalamus.

Patients

Patient 1

This female patient was 27 years of age at the time of surgery. TS symptoms first emerged in early childhood in the form of spitting and eye blinking. During adolescence, motor symptoms worsened and at the time of surgery, this patient presented with a permanent rotation of the right shoulder, a right tilted head posture and intermittent occasional vocalizations. Psychopharmacological treatments, including tiapridex, amisulpride, fluvoxamine, risperidone, clonidine and haloperidol, were not tolerated or did not lead to a satisfying tic reduction. Until surgery, the patient's continuous worsening of TS symptoms had resulted in a markedly impaired job performance and an insuperable feeling of shame when leaving the house. In addition, the severe tic symptomatology presented a burden to the intimate relationship patient 1 was maintaining at that time. The patient received left thalamic stimulation. Target coordinates were defined according to the AC/PC line: x=−8.5, y=−6.6 and z=−1.5. (Medtronic GmbH (Meerbusch, Germany), electrode model 3387).

Patient 2

The 39-year-old male patient presented with face and bilateral shoulder jerks and contractions of the left forearm, which first appeared during childhood but worsened during the years preceding surgery. Vocal tics in the form of sniffing and blowing one's nose added to the symptomatology. As a result of persistent TS symptoms in adulthood, the patient suffered from tic-related pain of the cervical and the thoracic spine. Treatment attempts before surgery involved behavior therapy and pharmacological treatment, including tiapridex, aripripazole, fluphenazine and clonidine, but did not lead to a successful improvement. Due to repeated medical leaves, the patient's loss of work was imminent and feelings of shame when leaving the house started to become a burden to the patient's relationship. The patient received right thalamic stimulation (Medtronic GmbH, electrode model 3387; x=8.9, y=−6.5 and z=−3.5).

Adjustment of stimulation parameters

Different stimulation parameters were tested during intraoperative test stimulation, thereby allowing an early assessment of both tic-suppression and also the subjective stimulation experience of each patient. Under the stimulation settings that were most effective in suppressing the tics, both patients reported an acute and pleasant feeling of inner appeasement. Postoperatively, all electrode contacts were repeatedly test-stimulated, but for both patients no stimulation setting appeared as effective as the setting identified as the most optimal setting during the intraoperative test stimulation.

As characteristic for thalamic stimulation, both patients described an instant feeling of dizziness, lasting for a few seconds only, when the stimulation settings were changed. Under higher voltages, patient 1 described disturbances of her fine motor skills. The patients reported no further side effects.

Testing

Next to inventories assessing the patients' satisfaction with major life aspects, such as emotional, social or occupational functioning, the ELSA–DBS project, as well as the KFO-219 project include a multitude of psychological and neuropsychiatric tests. The DBS outcome data that are reported here represent merely a selection of tests thereby encompassing measures of tic improvement (Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS), Modified Rush Videotape Rating Scale (MRVRS)), mood (beck depression inventory (BDI-2)), cognition (verbal fluency) and global functioning (global assessment of functioning). Data were gathered at baseline, 1 week, 3 months and 12 months after surgery by blinded raters trained in administering and evaluating the behavioral data.

Results

The stimulation parameters that appeared most effective and were not accompanied by adverse reactions were determined for both patients during a postoperative phase of adjustment (Table 1).

Table 1. Stimulation settings.

| Electrode settings | Amplitude | Frequency (Hz) | Pulse width (μs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 0−, 1−/case+ | 4.5 | 130 | 120 |

| Patient 2 | 1−, 2−/case+ | 3.1 | 90 | 120 |

Reduction of Tourette symptoms

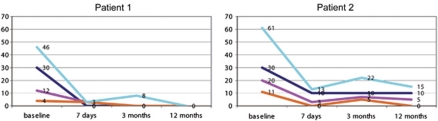

Intraoperative test stimulation already resulted in a substantial amelioration of tics. Evaluation of pre- and postoperative videotapes that were recorded to obtain the MRVRS score revealed a 100% TS symptom reduction in patient 1 (Video Supplement) and an at least 63% reduction of TS symptoms in patient 2. The patients' YGTSS scores revealed a similar picture. Again, patient 1 benefited markedly as indicated by a 100% improvement on all YGTSS sub scores from pre- to 12-months postsurgery assessment. Within the same time frame, patient 2 displayed a 100% improvement of vocal tics, a 75% reduction of both motor and total YGTSS scores and a 67% improvement in perceived impairment due to the disorder (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical course of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) scores of both patients from baseline to 12 months after surgery. Each colored line refers to a different YGTSS score. The following specifications apply for legend 1: line color: turquoise, blue, magenta and orange. Corresponding YGTSS score: total score, impairment score, motor score and vocal score.

DBS effects on mood

DBS did not impact negatively on the patients' mood (Table 2). Although patient 1 displayed a three-point increase on the BDI from baseline to 1-year follow-up, the increase was due to an unintended 16-pound weight loss, which according to the patient, was neither associated with a change in eating habits nor appetite.

Table 2. DBS outcome data for patient 1 and 2.

|

Baseline |

3 months |

12 months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |

| MRVRS | 13 | 13 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 |

| BDI-2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| GAF | 51 | 58 | 83 | 74 | 88 | 88 |

| Verbal fluency sumscore | 37 | 61 | 29 | 41 | 28 | 46 |

Abbreviations: BDI, beck depression inventory; DBS, deep brain stimulation; GAF, global assessment of functioning; MRVRS, Modified-Rush-Videotape Rating Scale.

DBS effects on global functioning

Both patients displayed a continuous improvement in global functioning during the 12-months interval of the study (Table 2).

DBS effects on cognitive functioning

One year after surgery, both patients displayed a reduced ability on a verbal fluency task that asked them to name as many words as possible starting with a certain letter, within a given period of time (1 min or 2 min). The four-letter sum score of patient 1 had decreased by 24%, and by 25% in patient 2, 1 year after surgery (Table 2).

Discussion

The pathophysiology of TS is thought to involve a dysfunction of basal ganglia-related circuits, which might be caused by hyperactive dopaminergic innervations.

A multitude of reports has been published showing that bilateral DBS of different structures in the assumed dysregulated loops is effective in diminishing TS symptoms,13 presumably by modulating the dopaminergic transmission.14 However, as both of our patients have experienced a major attenuation of their TS symptoms, unilateral DBS might, at least in some cases, be of comparable effectiveness.

To the best of our knowledge, there exist only a few reports about one-sided DBS in general15 and only one report about unilateral stimulation in TS specifically. Gallagher et al.16 reported about a TS patient, who initially received bilateral thalamic and internal pallidal stimulation. Due to infection, the left lead had to be removed. After removal, motor tics reappeared on the right side, whereas tics on the side contralateral to the functioning electrode remained absent. While this accidental finding strongly supports the notion of a lateralized dysfunction in TS,17 reports on DBS for PD indicate that unilateral stimulation might yet produce bilateral effects. Walker et al.,18 for example, found that unilateral STN stimulation did not only lead to a significant contralateral but also a significant ipsilateral improvement of motor symptoms in a sample of 37 PD patients at both a 3- and 6-month postsurgery assessment. However, in contrast to the contralateral UPDRS score, improvement of the ipsilateral UPDRS score did not anymore reach significance at another 12-month postsurgery assessment.

Our findings likewise support the notion that the effects of unilateral stimulation are not necessarily limited to the side contralateral to the electrode, as indicated by the 100% tic reduction 1 year after surgery in patient 1. Although tics were present at both sides of the body, it is possible that our patients benefited so markedly from the unilateral stimulation as both presented predominantly with one-sided tics. In line with this, Taba et al.8 found that unilateral stimulation of either the STN or the GPi yielded the best results in a subset of Parkinson patients that was characterized by a higher asymmetry index, that is lower contralateral than ipsilateral UPDRS scores.

Similar to these cases of successful unilateral stimulation in PD disease, the present results show that unilateral stimulation of those thalamic structures that have been targeted in the present two cases was able to profoundly improve motor TS symptoms. According to recent thalamic classifications, the VA, which embeds Hassler's ventrooralis anterior and the anterior part of the ventrooralis internus, receives pallidal and nigral input,12 and is therefore designated a motor structure within the thalamus. Hence, the pallidal and nigral afferents of the VA could explain the beneficial stimulation effects on the patients' motor TS symptoms. In contrast to this, appraising the motor effects of stimulating the VL, which encompasses Hassler's VOP, bears greater difficulties. Although the VOP is localized within the VL, which is mainly a cerebellar territory, physiological findings support the notion of the VOP receiving pallidal afferents. The classification of the VOP as either cerebellar or pallidal is therefore still being debated.11 Yet, the pallidal input to the VOP could likewise account for the witnessed attenuation of motor symptoms.

VA and VL are located within close proximity to the mediodorsal (MD) nucleus of the thalamus, which receives not only pallidal and nigral inhibitory input but also excitatory input from the amygdala,11 and is therefore part of the so-called limbic basal ganglia–cortex loop.19 To account for affective disturbances resulting from a co-stimulation of this seed region due to the narrow distance between VA, VL and MD, measures of the patients' mood had been taken pre- and postoperatively. As the data do not show an altered subjective perception of mood on the part of the patients, it can be assumed that an accidental co-stimulation of the MD did not occur. This notion is further supported by the finding that none of the patients described any olfactory deficits as a stimulation side effect although lesions of the MD often lead to deficits in olfactory processing.11

Concerning the effect of unilateral stimulation on cognition, our data do not parallel those of Huff et al.,15 who applied right-sided unilateral stimulation to the nucleus accumbens in 10 OCD patients. While the OCD patients improved slightly, although not significantly, on a verbal fluency examination task, our patients showed a decreased ability on the same task 1 year after electrode implantation. Likewise, Ackermans et al.20 found that bilateral thalamic stimulation impacted negatively on letter fluency in four of six TS patients. A possible explanation for these conflicting findings is that the occurrence of side effects on cognition might vary as a function of target selection, with thalamic stimulation having a greater impact on verbal fluency than nucleus accumbens stimulation. Unilateral thalamic stimulation, however, could thereby possibly curtail the impact of DBS on cognition.

A drawback of the present study is its single-blinded design. That is, only the clinically trained researchers gathering the behavioral data were blind to the stimulation status while the patient was informed whether the stimulation was currently switched on or off. To at least partly account for the possibility of a subjective bias on part of the patient due to this shortcoming, the YGTSS and the MRVRS were each evaluated by a different independent and clinically trained rater. Given the blinding of both raters and the high accordance between the level of improvement of TS symptomatology found with both test instruments (100% each for patient 1, and 63 and 75% for patient 2, respectively), it is highly unlikely that the single-blinded design could have accounted for a placebo effect that powerful. Yet, a double-blinded design, in which the patients would as well have been unaware of the stimulation status, would have been most optimal.

Another important aspect that must not be neglected is that both patients presented with prominent motor but only mild vocal tics. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the outstanding effects of DBS on tic reduction found here are generalizable to patients suffering predominantly from vocal tics. Hence, another limitation of the present report is that it is restricted to two patients only and does therefore not encompass a sample of patients that is more diverse in terms of TS symptomatology.

Yet, the beneficial bilateral effects that could be achieved for both patients are promising and should therefore encourage a further investigation of the prospect of impacting upon dysfunctional bilateral basal ganglia loops by unilateral stimulation. Although DBS is a relatively safe procedure, the risk of adverse events, such as infection or bleedings, could be markedly reduced if there was a common understanding about which patients could be satisfactorily treated by solely unilateral stimulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (ELSA-DBS grant; ethical, legal and social aspects of DBS) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO-219 grant; Basal Ganglia - Cortex Loops: Mechanisms of Pathological Interactions and Their Therapeutic Modulation) for financial support.

CB, DH, JD, CW and SH reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest in this investigation. JK received financial support for DBS studies (not the present investigation) from Medtronic GmbH (Meerbusch, Germany). DL reports having received financial assistance for travel to congresses from Medtronic AG. MM has occasionally received honoraria from Medtronic for lecturing at conferences and consulting. VS disclosed financial support for studies and travel to congresses by lecture fees from Medtronic AG and Advanced Neuromodulation Systems. He also reported to be coholder of patents on desynchronized brain stimulation and joint founder of ANM-GmbH Jülich, a company that intends to develop new stimulators.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Kurlan R. Tourette's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2332–2338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1007805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandewalle V, van der Linden C, Groenewegen HJ, Caemaert J. Stereotactic treatment of Gilles de la Tourtete syndrome by high frequency stimulation of thalamus. Lancet. 1999;353:724. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houeto JL, Karachi C, Mallet L, Pillon B, Yelnik J, Mesnage V, et al. Tourette's syndrome and deep brain stimulation. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:992–995. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.043273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta M, Sassi M, Ali F, Cavanna AE, Servello D. Neurosurgical treatment for Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome: the Italian perspective. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermans L, Temel Y, Cath D, van der Linden C, Bruggeman R, Kleijer M, et al. Deep brain stimulation in Tourette's syndrome: two targets. Mov Disord. 2006;21:709–713. doi: 10.1002/mds.20816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela Filho O, Ragazzo PC, Silva DJ, Souza JT, Oliveira PM, Ribeiro TM. Bilateral GPe-DBS for Tourette's syndrome. Neuro Target. 2008;3:65. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn J, Lenartz D, Mai JK, Huff W, Lee SH, Koulousakis A, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens and the internal capsule in therapeutically refractory Tourette-syndrome. J Neurol. 2007;254:963–965. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taba HA, Wu SS, Foote KD, Hass CJ, Fernandez HH, Malaty IA, et al. A closer look at unilateral versus bilateral deep brain stimulation: results of the National Institutes of Health COMPARE cohort. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:1224–1229. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.JNS10312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW, Walkup J, Frey KA, Como P, Cath D, Delong MR, et al. Patient selection and assessment recommendations for deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1831–1838. doi: 10.1002/mds.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassler R.Architectonic organization of the thalamic nucleiIn: Waiker AE, Schaltenbrand G (eds). Stereotaxy of the Human Brain Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany; 1982140–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mai J, Forutan F.ThalamusIn: Mai JK, Paxinos G (eds). The Human Nervous System Elsevier: San Diego, California, USA; (in press), pp620–679. [Google Scholar]

- Ilinsky IA, Kultas-Ilinsky K. Motor thalamic circuits in primates with emphasis on the area targeted in treatment of movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2002;17:9–14. doi: 10.1002/mds.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welter ML, Mallet L, Houeto JL, Karachi C, Czernecki V, Cornu P, et al. Internal pallidal and thalamic stimulation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:952–957. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.7.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernaleken I, Kuhn J, Lenartz D, Raptis M, Huff W, Janouschek H, et al. Bithalamical deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome is associated with reduction in dopaminergic transmission. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff W, Lenartz D, Schormann M, Lee SH, Kuhn J, Koulousakis A, et al. Unilateral deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in patients with treatment –resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: Outcomes after one year. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CL, Garell PC, Montgomery EB., Jr Hemi tics and deep brain stimulation. Neurology. 2006;66:E12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000190258.92496.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW. Basal ganglia dysfunction in Tourette's syndrome: a new hypothesis. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;25:190–198. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HC, Watts RL, Guthrie S, Wang D, Guthrie BL. Bilateral effects of unilateral subthalamic deep brain stimulation on Parkinson's disease at 1 year. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:302–310. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000349764.34211.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, Jenkinson N, Owen SL, Aziz TZ. Translational principles of deep brain stimulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:623–635. doi: 10.1038/nrn2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermans L, Duits A, van der Linden C, Tijssen M, Schruers K, Temel Y, et al. Double-blind clinical trial of thalamic stimulation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2011;134:32–844. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.