Abstract

Mineralocorticoid (MR) and glucocorticoid receptors (GR) are abundantly expressed in the limbic brain and mediate cortisol effects on the stress-response and behavioral adaptation. Dysregulation of the stress response impairs adaptation and is a risk factor for depression, which is twice as abundant in women than in men. Because of the importance of MR for appraisal processes underlying the initial phase of the stress response we investigated whether specific MR haplotypes were associated with personality traits that predict the risk of depression. We discovered a common gene variant (haplotype 2, frequency ∼0.38) resulting in enhanced MR activity. Haplotype 2 was associated with heightened dispositional optimism in study 1 and with less hopelessness and rumination in study 2. Using data from a large genome-wide association study we then established that haplotype 2 was associated with a lower risk of depression. Interestingly, all effects were restricted to women. We propose that common functional MR haplotypes are important determinants of inter-individual variability in resilience to depression in women by differentially mediating cortisol effects on the stress system.

Keywords: cortisol, depression, female prevalence, mineralocorticoid receptor, optimism, single-nucleotide polymorphisms

Introduction

A fundamental question in mental health research is why some individuals can cope with stress while others can't and become vulnerable for depression. Tipping the balance from resilience to vulnerability occurs upon dysregulation of brain mineralo- (MR)- and glucocorticoid receptors (GR), which mediate the action of the adrenal hormone cortisol on the initiation and termination of the stress response, respectively.1, 2 Chronically elevated cortisol activating GR is a known risk factor for depression3 and blockade of excess cortisol with GR antagonists has been successful in the treatment of psychotic depression.4 In addition, abundant evidence points to MR activation in the limbic brain as a potential antidepressant strategy.3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Previously we identified two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located in exon 2 of the MR (NR3C2) gene (−2G/C and I180V; Figure 1a) that influence MR translation and/or its capacity to transactivate target genes in cell lines. These two SNPs caused differential neuroendocrine and sympathetic responses to psychological stressors.10, 11 In addition, these SNPs were associated with differences in the cortisol awakening response, depending on an interaction with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or after dexamethasone treatment.12, 13 Most of the associations found with the MR SNPs were sex-dependent. Here, we assessed whether the functional SNPs in exon 2 are linked to SNPs in the MR promoter region, which potentially influence MR transcription and its dynamic expression. We identified a common gene variant (haplotype 2, frequency ∼0.38) that enhances MR synthesis. Next, our objective was to examine if the MR haplotypes protect against depression. We discovered that MR haplotype 2 enhances resilience to depression, particularly in women and have replicated this finding in three independent studies, including data from a genome-wide association study.

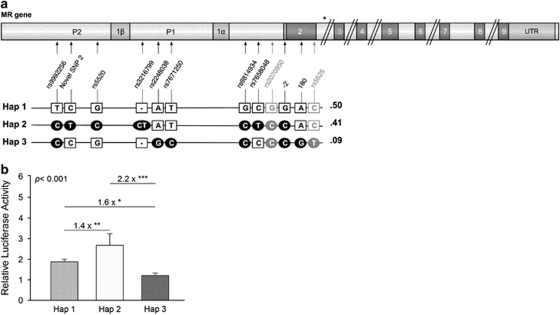

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic overview of the human mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) gene with its respective 5′ haplotypes and haplotype frequencies. Three haplotypes along a stretch of 4 kb of the 5′ untranslated region were identified based on the genotypes of 50 anonymous DNA samples and include eight single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The positioning and relation with the -2G/C (rs2070951) and I180 V (rs5522, control SNPs in grey) SNPs are indicated, which tag these three most common haplotypes. The haplotypes are not linked to common SNPs more 3′ in the MR gene sequence, as a recombination hotspot exists in intron 2 (asterisk). (b) Mean activity (±s.e.m., N=6) of the human MR promoter region associated with haplotype 1, 2 or 3. The figure shows representative results (of three independent experiments with two distinct sets of plasmid isolates) on the comparison of promoter activities associated with haplotype 1–3 relative to the activity of the pGL3-Basic plasmid, which activity was set to 1 (data not shown). Activities differed significantly between the three MR plasmids (F(2,15)=27.98; P<0.001). Data are firefly luminescent signals divided by the Renilla luminescent signals, hereby controlling for cell death and variability in transfection efficiency. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Abbreviations: P1, promoter 1; P2, promoter 2; UTR, untranslated region.

Materials and methods

SNP analysis of the MR promoter region and luciferase assays

A total of 50 anonymous blood samples were obtained from the general physician laboratory in Leiden. DNA was isolated and the MR gene's coding sequence was analyzed for the occurrence of SNPs, including the −2G/C and I180 V SNPs, as described by DeRijk et al.14 In the present study, a region of almost 4 kb (3870 basepairs) of the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) was amplified with multiple PCR reactions followed by sequence analysis. Based on the literature and with in silico analysis we verified whether the common SNPs in this 4 kb promoter region were located in (predicted) transcription factor- (TF) binding sites, glucocorticoid responsive elements, binding of other steroid receptors (using the TF databases TRANSFAC15 and JASPAR16), or whether they would influence splicing of the MR transcripts.17

Haplotypes were reconstructed and for the three haplotypes with a frequency above 0.03 (designated as haplotype 1, 2 or 3) firefly luciferase reporter plasmids were constructed using the pGL3-Basic plasmid (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands). Two separate bacterial cultures and plasmid DNA isolates were prepared for each of the three haplotype-firefly luciferase constructs on two distinct days. Differential promoter activity between the three haplotypes was tested in human neuroblastoma cells (BE(2)-M17; Health Protection Agency Culture Collections, Cat. No. 95011816). Cells were transfected with 200 ng of haplotype-firefly luciferase construct 1, 2 or 3, together with 10 ng of a Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL4.74 (hRluc/TK), Promega). In separate culture wells, 100 ng of pGL3-Basic or pGL3-Control vector (Promega) were transfected, functioning as, respectively, background measurement or positive control. Each construct was transfected in six separate wells. After 48 h of incubation, cells were lysed and firefly and Renilla luminescent activity was assessed. Experiments were performed three times on separate days for each of the two sets of plasmid DNA isolates. Relative light units were calculated by dividing the firefly luminescent signals by the corresponding Renilla luminescent signals in order to correct for variability in transfection efficiency or cell death (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1 for further details).

Study 1: association with dispositional optimism

The first study group consisted of 450 elderly men and women who previously participated in the 9.1-year longitudinal Arnhem Elderly Study18 (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 4 for sample characteristics). Dispositional optimism was assessed using the Dutch Scale of Subjective Well-being for Older Persons (Groningen University, The Netherlands).19 The Dutch Scale of Subjective Well-being for Older Persons consists of five subscales including Health, Self-respect, Morale, Contacts and Optimism. For each subscale an individual could indicate to what extent it conforms to a particular statement on a 3-point scale (from 0 to 2). An example of one of the seven statements for optimism is: ‘I still have positive expectations concerning my future' (our translation). A mean item score for the optimism subscale was calculated and multiplied by 10, resulting in scores ranging from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating a higher level of optimism. Participants provided a blood sample for genotype analysis. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Wageningen University (Wageningen, The Netherlands). All participants provided written informed consent.

Study 2: association with cognitive reactivity to sad mood

As a follow-up on the first study, this second study was performed to test the association between the MR haplotypes and hopelessness, which is by definition inversely related to optimism. The second study group consisted of 150 university students (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 5 for sample characteristics). Thoughts of hopelessness during sad mood as well as several other measures of cognitive reactivity were assessed with the Leiden Index of Depression Sensitivity-revised.20 It is a self-rating questionnaire consisting of 34 items and six subscales, namely Hopelessness/Suicidality, Acceptance/Coping, Aggression, Perfectionism/Control, Risk Aversion and Rumination. An example of one of the five statements for Hopelessness/Suicidality is: ‘When I feel down, I more often feel hopeless about everything'. Participants had to indicate whether and how their thinking patterns change when they experience mild dysphoria, by scoring each item on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 0 ‘not at all' to 4 ‘very strongly'. Scores for Hopelessness/Suicidality range from 0 to 20.

In addition, scores were assessed for neuroticism (Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Five-Factor Inventory21), current symptoms of anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale22) and the presence of current and past depression (Major Depression Questionnaire23). Participants provided a saliva sample for genotype analysis. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center (Leiden, The Netherlands). All participants gave written informed consent.

Study 3: association with the risk of depression

To test association of the MR haplotypes with major depressive disorder (MDD) in a larger study sample, data were used from a genome-wide association study, the GAIN-MDD study.24 MDD cases (n=1730) were mainly from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA; http://www.nesda.nl).25 The patients included here had a lifetime diagnosis of MDD as diagnosed with the DSM-IV Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 2.1.26 The control subjects (n=1793; mean age±s.d.=45.1±14.1), having no report of MDD, were mainly from the Netherlands Twin Registry (http://www.tweelingenregister.org).27 Participants provided a blood sample for genotype analysis. The NESDA and The Netherlands Twin Registry studies were approved by the Central Ethics Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. All subjects provided written informed consent (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 6 for sample characteristics).

DNA isolation and genotyping

DNA was isolated from the blood (first and third study group) or saliva (second study group) samples and genotypes were assessed for the functional MR −2G/C (rs2070951_GC) and I180V (rs5522_AG) SNPs, which tag the three most common haplotypes localized in exon 2 and extending into the promoter region (Figure 1a; see Supplementary Methods and Sullivan et al.24 for further details).

Statistical analysis

SNP allele frequencies were tested for Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium using HaploView (version 4.1. for Mac OS X; available online, http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/haploview).28 In addition, HaploView was used to assess inter-marker linkage disequilibrium (LD) scores (expressed as D' and r2) between the MR SNPs and to reconstruct haplotypes. Individual haplotypes were reconstructed in SNPHAP (version 1.3; available online, http://www-gene.cimr.cam.ac.uk/clayton/software/snphap.txt).

To compare promoter activities between the three constructs containing haplotype 1, 2 or 3, a one-way analysis of variance was conducted followed by a post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test.

Differences between men and women on the various demographics and health factors were tested using an independent-samples t-test, a χ2-test or a Mann–Whitney U-test, where appropriate. A square-root transformation was performed for the Hopelessness/Suicidality, Acceptance/Coping, Aggression, Perfectionism/Control, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-depression and -total scales and for age of the student participants of study 2 (when comparing age between men and women) in order to normalize their distributions. Figures 2, 3a and b and Supplementary Tables 4–6 represent untransformed data, while statistical tests were performed on transformed data where appropriate (indicated with an asterisk). Supplementary Table 7 represents transformed data and statistical analysis where appropriate.

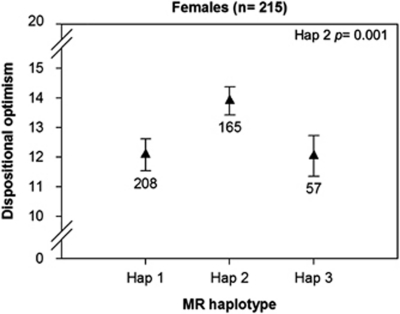

Figure 2.

Results of study 1, showing crude mean scores (±s.e.m.) for dispositional optimism according to three 5′ mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) haplotypes in women. Dispositional optimism scores increased 1.7 per haplotype 2 allele (on a range of 0 to 20) only in women (explained variance=7%) and not in men (Supplementary Table 7). To determine the effect of two haplotype 2- or 3-alleles, the effect calculated for one allele can be multiplied by 2. P-values represent adjusted comparison of haplotype 2 to the reference (haplotype 1 carriers) with linear regression. Note the breaks in the y axis.

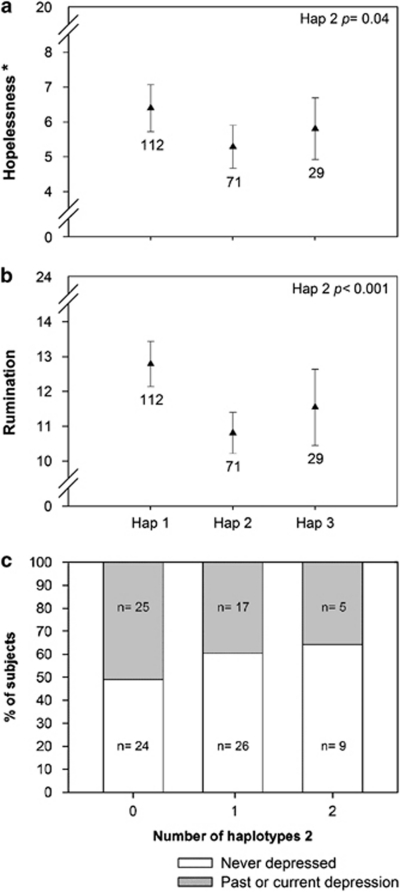

Figure 3.

(a, b) Results of study 2, showing crude mean scores (±s.e.m.) for cognitive reactivity according to three 5′ MR haplotypes in women. Hopelessness (a) scores decreased 1.1-fold per haplotype 2 allele (on a range of 0 to 20), only in women (explained variance=4%) but not in men (Supplementary Table 7). In addition, rumination (b) scores were lower only in the female haplotype 2 carriers, with a 2.1-fold reduction per haplotype 2 allele (on a range of 0 to 24; explained variance=11%). To determine the effect of two haplotype 2- or 3-alleles, the effect calculated for one allele can be multiplied by 2. P-values represent adjusted comparison of haplotype 2 to the reference (haplotype 1 carriers) with linear regression. Note the breaks in the y axis. * Statistical test based on transformed data. (c) Percentage of female students reporting a diagnosis for depression according to the number of haplotypes 2 (odds ratio=0.40; 95% confidence interval=0.16–0.95; P=0.04). For statistical test results see also Supplementary Table 8a.

For association analysis with the haplotypes, three dummy variables were created indicating whether a person carried zero, one or two alleles of haplotype 1, 2 or 3. With linear regression analysis the mean effect of one haplotype 2- or 3-allele on a psychological trait was determined relative to the reference group (scores in haplotype 1 carriers). To determine the effect of two haplotype 2- or 3-alleles, the effect calculated for one allele can be multiplied by 2. Because of possible sex differences, statistical interaction between the MR haplotypes and sex was determined by adding the two appropriate interaction terms to the model. Next, regression analyses were repeated in sex strata. In sensitivity analyses in study 2 subjects without a European ancestry were excluded. In study 2 associations between the haplotypes with the other Leiden Index of Depression Sensitivity-revised subscales, neuroticism and current symptoms of anxiety and depression was also tested. Logistic regression was used to test association with self-reported diagnosis of depression. In the third association study, logistic regression was used to test association with MDD. As sex-dependent associations are potentially due to differences in circulating sex steroids, the group of women of the GAIN-MDD study was additionally divided in women older and younger than the mean age for menopause (∼51 years). In all three studies, analysis was repeated while adjusting for potential confounding effects of sex (in the total group) and age.

A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. A Bonferroni correction was applied where appropriate. All statistical analysis was performed in SPSS, version 16.0 for Mac OSX (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

MR SNP and haplotype frequencies and predicted effects on MR transcription

In all, 16 SNPs were detected along the 4 kb MR promoter region. As of October 2011, three SNPs were still not reported elsewhere (GRCh37:4:149362585:149366454, Ensembl; novel SNP 1, 2 and 3). All allele frequencies of the MR SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (P>0.10; see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1 for an overview of individual SNP genotype frequencies and inter-marker r2 scores). Reconstruction of MR haplotypes resulted in one haplotype bin that was highly linked to the previously described MR -2G/C and I180V SNPs. On the basis of previous research by our lab and the HapMap database (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) we know that these exon 2 SNPs are not linked to the rest of the MR gene sequence starting in intron 2.14

Pooling the low frequency haplotypes (freq. <0.03) with the high frequency haplotypes (based on the −2G/C and I180V genotypes) resulted in three haplotypes with frequencies of 0.50, 0.41 and 0.09, which differ in eight MR 5′ UTR SNPs (Figure 1a). These eight MR 5′ UTR SNPs were not located at previously described TF-binding sites. However, in silico analysis using two different databases consistently predicted the SNP rs5520 to affect the number of possibilities for Sp1 binding, while the SNP rs3216799 influences Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1 b binding (see Supplementary Table 3). Of interest is that one database predicted the SNP 2248038 to affect a glucocorticoid responsive element-consensus sequence by influencing binding of NR3C1 (or GR), while the SNP rs3216799 was predicted to be located 1 nucleotide next to a glucocorticoid responsive element (data not shown). The SNPs did not alter predicted splicing of the MR transcripts.

Promoter haplotype 2 results in higher MR expression

Results of three independent experiments with two separate sets of plasmid isolates were highly similar. All three MR promoter regions were active under non-stimulating conditions, as the constructs resulted in a signal that was higher compared with the pGL3-Basic plasmid (Figure 1b). Activities between the three plasmids differed significantly (F(2,15)=27.98; P<0.001). Haplotype 2 resulted in a 1.4 times higher promoter activity compared with haplotype 1 (P<0.01) and a 2.2 times higher promoter activity compared with haplotype 3 (P<0.001).

Haplotype frequencies in the three association study groups

Allele frequencies of the MR SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (P>0.10). Genotype and haplotype frequencies (see Supplementary Tables 4–6) and inter-marker correlations between the MR -2G/C (rs2070951) and I180V (rs5522) SNPs (D'=1.0; r2=0.15) were similar as previously found.10

Study 1: MR haplotype 2 associates with higher dispositional optimism, specifically in women

MR haplotype 2 (freq. 0.36) was associated with higher dispositional optimism when compared with the reference group (haplotype 1 carriers; P=0.01; Supplementary Table 7). Importantly, a MR haplotype 2-by-sex interaction effect was found (P=0.01). Data stratification for sex revealed that only in women haplotype 2 was related to higher levels of dispositional optimism (Figure 2) with an explained variance was 7% (R2change=0.07), while no significant effect was found in men.

Study 2: MR haplotype 2 associates with fewer thoughts of hopelessness, specifically in women

Haplotype 2 was significantly associated with fewer thoughts of hopelessness, again only among female students (Figure 3a), with an explained variance of 4% (R2change=0.04).

Interestingly, additional analysis of the other five Leiden Index of Depression Sensitivity-revised subscales showed that in women haplotype 2 was also significantly associated with lower scores for aggression (P=0.007), risk aversion (P=0.05) and importantly, rumination (Figure 3b; P<0.001; after a Bonferroni correction for in total twelve tests for the association with six subscales in both sexes, with a significance threshold of P<0.004, this is still significant). Moreover, in women MR haplotype 2 associated with lower neuroticism scores (P=0.04), a lower odds ratio for self-reported diagnosis of depression according to a dominant model (0.40; 95% confidence interval=0.16–0.95; P=0.04; Figure 3c and Supplementary Table 8a; similar results were found with a linear model but showed smaller effect sizes) and a trend was found for less symptoms of depression (P=0.07, see Supplementary Results and Supplementary Table 7).

Results strengthened after excluding subjects (22 women, 4 men) who indicated that one or both of their parents did not have a European ancestry or who did not respond to this question.

Study 3: MR haplotype 2 associates with a lower risk of major depressive disorder, specifically in women

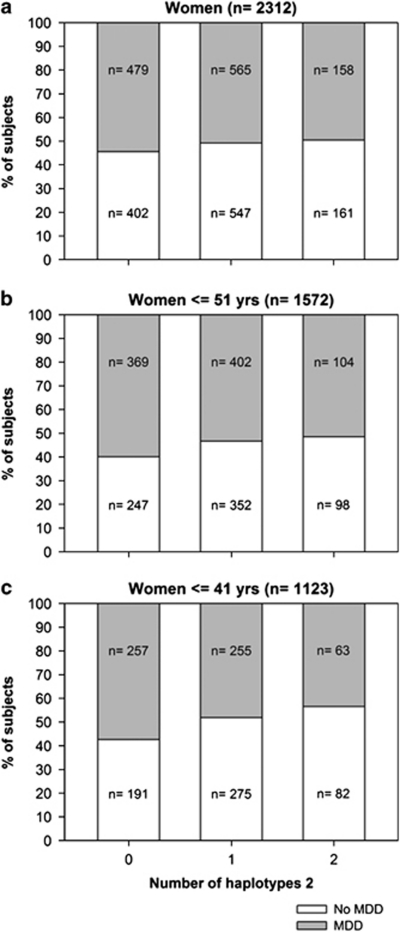

The data of study group 3 were analyzed in two steps and revealed that MR haplotype 2 was associated with a lower risk of depression again only in women and not in men, but strongly depending on whether the women were aged above or below the mean age for menopause (∼51 years). In the first step a trend was found for an association between MR haplotype 2 and a lower odds ratio for MDD in the total group of women (0.85; 95% confidence interval=0.72–1.02; P=0.08) and not in men (P=0.72), again according to a dominant model (Figure 4a and Supplementary Table 8b; similar results were found with a linear model but showed smaller effect sizes). Importantly, data stratification for the mean age for menopause in the second analysis step (MR haplotype 2-by-age split at 51 years interaction P=0.004) showed that MR haplotype 2 associated with a lower odds ratio for MDD specifically in the women with an age ⩽51 years (0.75; 95% confidence interval=0.60–0.93; P=0.009; after a Bonferroni correction for in total four tests for association analysis within both sexes and within the two age groups, with a significance threshold of P<0.0125, this is still significant; Figure 4b). The association particularly existed in the women with an age ⩽41 years (0.66; 95% confidence interval=0.52–0.86; P=0.002; Figure 4c; MR haplotype 2-by-age split at 41 years interaction P=0.008).

Figure 4.

Results of study 3, showing the percentage of women diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) according to the number of haplotypes 2. Results are presented for the total group of women (a) (odds ratio=0.85; 95% confidence interval=0.72–1.02; P=0.08), for the women aged ⩽51 years (odds ratio=0.75; 95% confidence interval=0.60–0.93; P=0.009) (b), or for the women aged ⩽41 years (odds ratio=0.66; 95% confidence interval=0.52–0.86; P=0.002) (c). MDD cases were mainly from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety cohort (NESDA),25 healthy controls were mainly from the Netherlands Twin Registry (NTR).27 For statistical test results see Supplementary Table 8b.

Discussion

The findings show that in three distinct groups of subjects the common and functional MR haplotype 2 was associated with optimism and a lower risk of depression in women. Haplotype 2, consisting of the known −2G/C and I180V SNPs11, 13, 29 and several promoter SNPs results in higher MR activity at the transcriptional, translational and transactivational level.10 Previously, MR expression was found to be decreased in the limbic brain of depressed subjects.6 Moreover, the MR is induced by antidepressant treatment, with MR induction potentially contributing to antidepressant treatment success.8, 9 MR agonists and antagonists either enhance or suppress antidepressant efficacy, respectively,5, 7 whereas modulatory effects of SNPs in the MR gene on the cortisol response to stress have been reported.10, 11 This implicates cortisol action via the MR as an important determinant of the inter-individual differences in stress responsiveness and vulnerability for depression. Indeed, in a previous study an association was found between the MR I180V SNP and geriatric depression.29

Possibly the MR promoter SNPs are to a large extent responsible for the inter-individual differences. MR expression is highly dynamic, showing changes during development, aging and after physical or psychological stress.30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 Context-dependent changes in MR expression can be established by distinct 5′ MR mRNA transcripts (MRα and MRβ), each having its own promoter containing regulatory elements and showing differential expression depending on tissue, time and availability of steroids and stress.6, 30, 36, 37, 38 SNPs may result in differential expression of MRα vs MRβ by affecting TF binding or splicing. Two of the eight common 5′ UTR SNPs were consistently predicted to influence TF binding while a third SNP was predicted to affect a glucocorticoid responsive element-consensus sequence (although not consistent). None of the SNPs was predicted to affect potential binding sites for sex steroids. Additional in vitro assays, like electrophoretic mobility shift assays, are necessary to identify allele-specific TF binding.

Intriguingly, the MR haplotype 2 appears to establish a lower risk of depression diagnosis only in women below 51 and in particular below 41 years of age. This suggests that female sex steroids may interact with the MR gene, thereby modulating resilience. The MR haplotypes are known to confer differences in MR activity with varying ligand availability, while hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) responses to stress are sex-specific.10, 39 Moreover, estrogens and progesterone are known to modulate MR mRNA and/or protein expression, with possible consequences for stress-reactivity.40, 41 These effects of sex steroids are superimposed on the remarkable promiscuity of the brain MR, which can bind also aldosterone and progesterone, but is particularly occupied by the much higher concentrations of circulating cortisol. This is because the cortisol-inactivating enzyme typical for aldosterone selectivity of the MR in kidney epithelial cells is absent in brain.42 However, no significant interaction effect was found between the haplotypes and the use of oral contraceptives (data not shown). Furthermore, the age difference in the association between the MR haplotypes and depression diagnosis may also be because of the impact of genetic factors, which is known to be larger for early-onset rather than late-onset depression.43 Although study group 1 and particularly study group 2 were small, with a rather low power to detect haplotype-related differences, the three independent studies, including the larger genome-wide association study dataset, all pointed to similar and significant associations.

In the limbic brain higher MR activity implies an enhanced reaction to novel information, allowing the individual to better appraise and perceive a new experience as either stressful or not. Individuals at risk of depression are thought to cope less efficiently with challenges,44 a phenomenon clearly linked to cortisol resistance in the brain to which haplotypes 1 and 3 with reduced activity of the MR may contribute. Also, hopelessness and rumination associated with these haplotypes are risk factors for depression; rumination is a strong predictor of depressive episodes (correlation=0.42 for previous Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) depression, 0.55 for current BDI depression), whereas hopelessness is not only a predictor of depressive episodes (correlation=0.57 for previous BDI depression, 0.40 for current BDI depression), it is also related to suicidal ideation during and between depressive episodes.45, 46, 47 In contrast, the dispositional optimism associated with haplotype 2 is a rather stable trait that relates to successful coping with stressful experiences and predicts a lower risk of depression (Spearman's correlation coefficient=−0.50 to −0.63 for depressive symptoms among elderly during 15 years of follow-up).48, 49

Our data strengthen the hypothesis that disturbed cortisol effects through impaired central MR signaling underlie in part the pathophysiology of depression.1, 3 The MR mediates cortisol-enhanced metaplasticity in the limbic brain involving the recently discovered membrane variants50 and the cortisol effects on appraisal, cognitive and behavioral flexibility and emotions.29, 51, 52, 53, 54 As the hormone cortisol drives gene-environment interaction, for better, but also for worse, the data raise the possibility that the cortisol-MR complex functions similarly as the recently designated ‘plasticity genes' (like the serotonin transporter gene with its well-known 5-HTTLPR polymorphism), with the reactive alleles rendering an individual more susceptible to adverse conditions, but also providing a benefit under supportive conditions.55

Here, we show that men's susceptibility to depression does not seem to be modulated by MR gene variability, while women's susceptibility depends on whether they carry MR haplotype 1 or 3 vs haplotype 2. That the MR haplotype 2 enhances psychological resilience particularly in women is fascinating considering the twice higher prevalence of depression in women.56 The finding provides a new lead towards a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this devastating affective disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicole Datson for critically reading the manuscript and the useful suggestions. The authors thank H Eka, D Suchiman and Patrizia Rizzu for SNP genotyping. This research was supported by the Netherlands Brain Foundation (15F07(2).24, 10F02(2).37), the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, NWO (VICI 453-06-005, SPI 56-464-14192), International Research Training Group IRTG funded by the DFG (GRH 1389/1) and NWO (DN95-420), psychiatric hospital Rivierduinen, ZonMW (904-61-090, 904-61-193, 480-04-004; 400-05-717), Center for Medical Systems Biology (NWO Genomics), Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, Geestkracht program (10-000-1002), the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the Foundation for the US NIH and NIMH (MH081802), European Research Council (ERC-230374), ESF Eurostress and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Karst H, DeRijk R, de Kloet ER. The coming out of the brain mineralocorticoid receptor. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:477–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBattista C, Belanoff J, Glass S, Khan A, Horne RL, Blasey C, et al. Mifepristone versus placebo in the treatment of psychosis in patients with psychotic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. The rationale for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor (CRH-R) antagonists to treat depression and anxiety. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:181–214. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)90056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klok MD, Alt SR, Irurzun Lafitte AJM, Turner JD, Lakke EAJF, Muller CP, et al. Decreased expression of mineralocorticoid receptor mRNA and its splice variants in postmortem brain regions of patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte C, Hinkelmann K, Moritz S, Yassouridis A, Jahn H, Wiedemann K, et al. Modulation of the mineralocorticoid receptor as add-on treatment in depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proof-of-concept study. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;44:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckl JR, Fink G. Antidepressants increase glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor mRNA expression in rat hippocampus in vivo. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;55:621–626. doi: 10.1159/000126180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zobel AW, Schulze-Rauschenbach S, von Widdern OC, Metten M, Freymann N, Grasmader K, et al. Improvement of working but not declarative memory is correlated with HPA normalization during antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen N, Bellingrath S, de Kloet ER, Zitman FG, DeRijk RH, Kudielka BM, et al. Human Mineralocorticoid Receptor (MR) gene haplotypes modulate MR expression and transactivation: implication for the stress response. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRijk RH, Wust S, Meijer OC, Zennaro MC, Federenko IS, Hellhammer DH, et al. A common polymorphism in the mineralocorticoid receptor modulates stress responsiveness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:5083–5089. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klok MD, Vreeburg SA, Penninx BWJH, Zitman FG, de Kloet ER, DeRijk RH. Common functional mineralocorticoid receptor polymorphisms modulate the cortisol awakening response: interaction with SSRIs. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen N, Kumsta R, Entringer S, de Kloet ER, Zitman FG, DeRijk RH, et al. Functional mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) gene variation influences the cortisol awakening response after dexamethasone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRijk RH, de Kloet ER, Zitman FG, van Leeuwen N. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Gene Variants as Determinants of HPA Axis Regulation and Behavior. Endocr Dev. Karger, Basel. 2011;20:137–148. doi: 10.1159/000321235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matys V, Fricke E, Geffers R, Gossling E, Haubrock M, Hehl R, et al. TRANSFAC: transcriptional regulation, from patterns to profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:374–378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engstrom P, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D91–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese MG, Eeckman FH, Kulp D, Haussler D. Improved splice site detection in Genie. J Comput Biol. 1997;4:311–323. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1997.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM, Zitman FG, Hoekstra T, Schouten EG. Dispositional optimism and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a prospective cohort of elderly dutch men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1126–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempelman CJJ. Welbevinden bij ouderen: Konstruktie van een Meetinstrument (Well-being in the Elderly: Development of the Scale Subjective Well-being Older Persons; in Dutch). Doctoral Dissertation. University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does W. Cognitive reactivity to sad mood: structure and validity of a new measure. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:105–120. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra HA, Ormel J, de FruytF. NEO-PI-R Handleiding. Hogrefe Uitgevers BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27:363–370. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does AJW, Barnhofer T, Williams JMG.The Major Depression Questionnaire (MDQ) . www.dousa.nl/publications , 2003

- Sullivan PF, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, James MR, Smit JH, Zandbelt T, et al. Genome-wide association for major depressive disorder: a possible role for the presynaptic protein piccolo. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:359–375. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Nolen WA, Spinhoven P, et al. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:121–140. doi: 10.1002/mpr.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, de Geus EJ, Vink JM, Stubbe JH, Distel MA, Hottenga JJ, et al. Netherlands Twin Register: from twins to twin families. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:849–857. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuningas M, de Rijk RH, Westendorp RG, Jolles J, Slagboom PE, van Heemst D. Mental performance in old age dependent on cortisol and genetic variance in the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1295–1301. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez DM, Lopez JF, Morano MI, Kwak SP, Watson SJ, Akil H. Alpha, beta, and gamma mineralocorticoid receptor messenger ribonucleic acid splice variants: differential expression and rapid regulation in the developing hippocampus. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3165–3177. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesing A, Bilang-Bleuel A, Droste SK, Linthorst AC, Holsboer F, Reul JM. Psychological stress increases hippocampal mineralocorticoid receptor levels: involvement of corticotropin-releasing hormone. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4822–4829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04822.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, Johansson IM, Soderstrom I, Lai M, Gido G, Wieloch T, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor expression and increased survival following neuronal injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1549–1555. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topic B, Oitzl MS, Meijer OC, Huston JP, de Souza Silva MA. Differential susceptibility to extinction-induced despair and age-dependent alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and neurochemical parameters. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;58:138–153. doi: 10.1159/000182890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Enthoven L, van Woezik JH, Levine S, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS. The dynamics of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during maternal deprivation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eekelen JA, Oitzl MS, De Kloet ER. Adrenocortical hyporesponsiveness and glucocorticoid feedback resistance in old male brown Norway rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:B83–B89. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.2.b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zennaro MC, Farman N, Bonvalet JP, Lombes M. Tissue-specific expression of alpha and beta messenger ribonucleic acid isoforms of the human mineralocorticoid receptor in normal and pathological states. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1345–1352. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.5.3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang P, Rogalska J, Walker CA, Burke M, Seckl JR, Macleod MR, et al. Injury-induced mineralocorticoid receptor expression involves differential promoter usage: a novel role for the rat MRbeta variant. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;305:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zennaro MC, Le Menuet D, Lombes M. Characterization of the human mineralocorticoid receptor gene 5′-regulatory region: evidence for differential hormonal regulation of two alternative promoters via nonclassical mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1549–1560. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: a review. Biol Psychol. 2005;69:113–132. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Deterd CH, de Koning J, Helmerhorst F, de Kloet ER. The influence of ovarian steroids on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation in the female rat. J Endocrinol. 1995;144:311–321. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1440311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinkler M, Meyer B, Bumke-Vogt C, Grossmann C, Gruber U, Oelkers W, et al. Agonistic and antagonistic properties of progesterone metabolites at the human mineralocorticoid receptor. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:789–799. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckl JR. 11beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the brain: a novel regulator of glucocorticoid action. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:49–99. doi: 10.1006/frne.1996.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Fiske A, Gardner CO, Gatz M. Delineation of two genetic pathways to major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:808–811. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS. The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: implications for prevention and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:255–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antypa N, Van der Does AJW, Penninx BW. Cognitive reactivity: investigation of a potentially treatable marker of suicide risk in depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhofer T, Chittka T. Cognitive reactivity mediates the relationship between neuroticism and depression. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay EJ, Zitman FG, Kromhout D. Dispositional optimism and the risk of depressive symptoms during 15 years of follow-up: the Zutphen Elderly Study. J Affect Disord. 2006;91:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst H, Berger S, Erdmann G, Schutz G, Joels M. Metaplasticity of amygdalar responses to the stress hormone corticosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14449–14454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan R, Perlis RH, Fagerness J, Pizzagalli DA. The impact of mineralocorticoid receptor ISO/VAL genotype (rs5522) and stress on reward learning. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte C, Moritz S, Yassouridis A, Koop M, Madrischewski AM, Wiedemann K, et al. Blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor in healthy men: effects on experimentally induced panic symptoms, stress hormones, and cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:232–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oitzl MS, de Kloet ER. Selective corticosteroid antagonists modulate specific aspects of spatial orientation learning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:62–71. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinks V, van der Mark MH, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS. Differential MR/GR activation in mice results in emotional states beneficial or impairing for cognition. Neural Plast. 2007;2007:90163. doi: 10.1155/2007/90163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:746–754. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s001270050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.