Abstract

The offspring of older fathers have an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism. In light of the evidence implicating copy number variants (CNVs) with schizophrenia and autism, we used a mouse model to explore the hypothesis that the offspring of older males have an increased risk of de novo CNVs. C57BL/6J sires that were 3- and 12–16-months old were mated with 3-month-old dams to create control offspring and offspring of old sires, respectively. Applying genome-wide microarray screening technology, 7 distinct CNVs were identified in a set of 12 offspring and their parents. Competitive quantitative PCR confirmed these CNVs in the original set and also established their frequency in an independent set of 77 offspring and their parents. On the basis of the combined samples, six de novo CNVs were detected in the offspring of older sires, whereas none were detected in the control group. Two of the CNVs were associated with behavioral and/or neuroanatomical phenotypic features. One of the de novo CNVs involved Auts2 (autism susceptibility candidate 2), and other CNVs included genes linked to schizophrenia, autism and brain development. This is the first experimental demonstration that the offspring of older males have an increased risk of de novo CNVs. Our results support the hypothesis that the offspring of older fathers have an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia and autism by generation of de novo CNVs in the male germline.

Keywords: advanced paternal age, autism, behavior, copy number variation, C57BL/6J, schizophrenia

Introduction

The offspring of older fathers have an increased risk of a range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism,1 schizophrenia,2, 3 bipolar disorder4 and epilepsy.5 The mechanisms underlying the increased risk of various neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring of older fathers remain unclear; however, it has been proposed that de novo point mutations and copy number variants (CNVs) in the continually dividing spermatogonia in older males underlie this association.2, 6

Copy number variants refer to regions of the genome with deletions, inversions or expansions of ∼1 kb up to several 100 kb in size.7 These may occur throughout the genome, but are enriched in regions flanked by segmental duplication in both humans8, 9 and mouse.10, 11 When CNVs encompass genes, they can give rise to an increase or a decrease in gene copy number, or they can contribute to the generation of pseudogenes. CNVs have been associated with neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism,12, 13, 14 schizophrenia,15, 16, 17, 18 epilepsy19, 20 and mental retardation.21, 22 Carriers of such CNVs tend to present with a variable phenotype, and a number of these CNVs can occur in apparently healthy individuals.23

In light of the links between advanced paternal age (APA) and neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia and autism, various rodent-based models have been developed to explore the phenotypic correlates of APA.24, 25, 26 On the basis of an APA C57BL/6J mouse model, we have previously reported that the offspring of older sires had subtle changes in anxiety-related outcomes and changes in cortical thickness.27 To date, we have not explored our model with respect to de novo CNVs. In this preliminary study, we explored the feasibility of CNV detection in our APA model. We hypothesized that the offspring of older sires would have more de novo CNVs than would the offspring of control sires. As the offspring used in this study had also been assessed on selected behavioral tests and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we also had the opportunity to explore phenotypic correlates of identified CNVs as a secondary research question.

Materials and methods

Generation of control and APA families

Families with control sires and those with old sires were generated as described in detail elsewhere.27 Virgin 3-month-old (control) and 12–16-month-old (APA) male C57BL/6J mice were selected to sire offspring; each was time mated with a 3-month-old female of the same strain. Offspring from 3-month-old males were used as controls, whereas offspring from males aged 12–16 months comprised the APA condition. Offspring were housed in groups of two to five with littermates where possible, but always with offspring from the same paternal condition. Mice were obtained from the University of Queensland C57BL6/J (JAX) mouse stock, and all procedures were performed with approval from the University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee, under the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Guidelines. Further details are available in Supplementary Material S1.

Array hybridization and detection of CNVs

Two arrays were used in combination to identify CNVs. For genome-wide screening, a commercially available microarray-based Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) (Mouse Genome CGH 244A Oligo Microarray, Agilent Technologies Australia, Forest Hill, Victoria, Australia) was used, which contained 236 000 mapped 60-mer probes tiling the entire mouse genome at an average distance of ∼11 kb. CNVs occur with higher frequency in the vicinity of segmental duplication, and the genomic structure in these regions is often complex in nature.10 Furthermore, it becomes more difficult to distinguish a one-copy change in a target region already present in multiple copies in the general population, as the expected log(2) intensity ratio derived from a two-color array decreases as a function of increasing reference copy number. To address these considerations, a custom array targeting CNVs identified recently by She et al.28 in a comprehensive comparison of different strains with C57BL/6J was used. Designed by Dr S. Chong and printed by Agilent, this array contained 11 800 60-mer probes spread over the genome at random and 15 580 targeted probes printed in duplicate. Selecting CNVs that could be targeted with at least two pre-designed and computationally validated probes, the custom array achieved 40% coverage of the variant intervals mapped by She et al.28 The resulting probe spacing at CNV loci varied but averaged at 1.5 kb.

Using these two arrays, we examined CNVs in two APA and two control families (three offspring in each of the families and equal number of sexes within each experimental group; total offspring n=12). To control for sex chromosome loading, each female test sample was competitively hybridized against a common female reference sample, and each male test sample against a common male reference sample. A comparison of the references allowed detection of any bias in autosomal and pseudoautosomal regions where aberrations were identified on the arrays. Preparation and labeling of genomic DNA, array hybridization, scanning and feature extraction were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's recommended protocols. Arrays were analyzed further using the Agilent DNA Analytics v4.0.76 software to assure hybridization quality and to detect aberrations. Detected aberrations were subjected to further filtering to select distinct amplifications and deletions for further inspection. These procedures are described in detail in Supplementary Material S1.

Validation and examination of candidate CNVs in an independent sample

The candidate CNVs identified by arrays were validated with Sequenom (Sequenom, QLD, Australia), which combined competitive quantitative PCR and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry29, 30 (see Supplementary Material S1). In brief, assays were designed targeting regions of interest (seven CNVs in total and four control regions without genomic aberrations). CNV2 to CNV7 and control regions were targeted by one assay each. CNV1 was targeted by three assays. Using these same methods, we also evaluated the prevalence of the selected CNVs in an independent sample of 77 offspring. These additional offspring, which were generated from 10 APA and 10 control breeding pairs, included 18 APA female and 16 APA male offspring, as well as 24 control female and 19 control male offspring. On the basis of the combined samples, all families were carefully evaluated for de novo CNV aberrations in offspring. A CNV that was detected in an offspring but was not detected in either parent was classified as ‘de novo'.

Behavioral and neuroanatomical phenotyping

Behavioral phenotyping was conducted when the offspring were 10 weeks of age and on separate and consecutive days in the following order: elevated plus maze, hole board, light/dark emergence, 2-day forced swim test and 2-day novelty-suppressed feeding. The order of testing was such that the tests most sensitive to handling were performed first and those most stressful performed last. After 1 week of free feeding, animals were tested on a 3-day active avoidance and extinction protocol, tests for nociception and prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response. All behavioral observations were made blind to CNV status and recorded from a central overhead camera, which was attached to computerized tracking and event-recording software, EthoVision version 3.1 (Noldus, Wageningen, The Netherlands). Mice were acclimated to the testing room for 1 h before testing and all arenas and apparatus were cleaned between trials with 20% ethanol. After completion of behavioral testing, animals were killed with pentobarbitone and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde containing 1% of a separate MRI contrast-enhancement agent, Magnevist (gadopentetate dimeglumine; Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) to optimize gray/white matter boundaries). Immediately before imaging, the brains were suspended in fomblin. Animals were imaged in the 16.4-T microimaging facility (Centre for Advanced Imaging, University of Queensland). Using a 15-mm diameter solenoid coil, fast-low action shot images were obtained in three dimensions with 50-μm voxel resolution. Regions-of-interest volumetric estimates were derived using the OsiriX software package (Rosset; GNU General Public License) with boundaries determined from a mouse brain atlas.31 Brain regions assessed included the hippocampus, striatum, septum, corpus callosum and anterior commissure. All measurements were made blind to CNV status and analyzed as proportions of total brain volume. Further details of these measures are described in a related publication.27

Statistics and data analysis

We hypothesized that the offspring of older sires would have significantly more de novo CNVs than would the offspring of control sires. On the basis of the number of de novo CNVs in the offspring of the APA and control groups, the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (two-tailed) were calculated. As no CNVs were called in the control offspring, we used the Haldane correction by adding 0.5 to each cell in the table, to generate a finite odds ratio. For phenotype assessments, all offspring (regardless of paternal age) were assessed with either (1) t-tests, in which we could clearly allocate CNV present versus absent status, or regression analyses between the relative copy number and the outcome of interest, in which a CNV was prevalent and hypervariable.

Bioinformatic analysis of detected CNVs

The expression of genes in the mouse and the human brains was established using the Allen Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org/). The CNV regions were mapped to the human genome using the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). The association of these loci with human disease was established with the Sullivan Lab Evidence Project (https://slep.unc.edu/evidence/)32 and the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim)33, 34 databases. The occurrence of CNVs in the syntenic genomic regions in humans in control cases and cases with neurocognitive dysfunction was explored using the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/project.html),35, 36 the DECIPHER (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/) and the National Centre of Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) databases.

Results

Identification and prevalence of CNVs

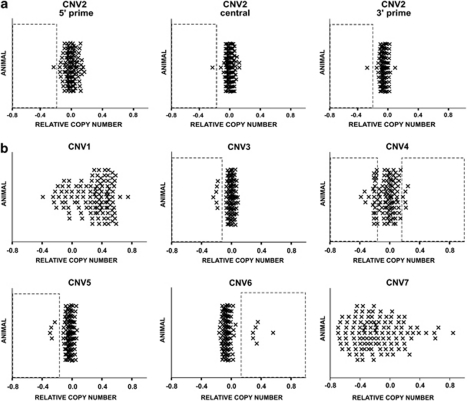

Seven CNVs were identified in the array-based sample. All of these CNVs were successfully validated by Sequenom (Supplementary Material S2). Each CNV contained or overlapped with at least one gene (Table 1, Supplementary Material S3). The prevalence of these CNVs in the combined samples is shown in Figure 1. The prevalence of CNVs within the total cohort of mice tested in this study (including the relationship of animals to each other, the experimental group status and the individual relative copy numbers (rCNs)) can be found in Supplementary Material S4.

Table 1. Details of CNVs identified in the array-based sample.

|

CNV number |

CNV1 |

CNV2 |

CNV3 |

CNV4 |

CNV5 |

CNV6 |

CNV7 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array | B | A | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | A |

| Total number of probes | 15 | 35 | 25 | 32 | 76 | 1172 | 33 | 428 | 12 | 8 |

| Size (bp) | 2 025 740 | 252 355 | 3 164 549 | 2 543 203 | 506 199 | 428 532 | 211 341 | 157 741 | 85 722 | 198 616 |

| Genomic coordinates | Chr4qA5 41.6–43.6 Mb | Chr5qG2 132.5–132.7 Mb | Chr7qA3 21.0–24.1 Mb | Chr14qA3 26.7–27.2 Mb | Chr14qD2 69.9–70.1 Mb | ChrXqF5 166.3–166.4 Mb | ChrXqF5 166.4–166.6 Mb | |||

| Genes | Cntfr, Dctn3, Arid3c, Sigmar1, Galt, Il11ra1, Il11ra2, Ccl27a, Ccl27b, Ccl19, Ccl21a, Ccl21b, Ccl21c, Dnajb5, Fancg, Pigo, Stoml2, Unc13b, Atp8b5, Vcp, Rusc2, Fam166b, Tesk1, Cd72, Sit1, Rmrp, Ccdc107, Car9, Tpm2, Tln1, Creb3, Gba2, Rgp1, Msmp,1700022I11Rik, 2810432D09Rik, 4933409K07Rik, B230312A22Rik, BC049635, E130306D19Rik, N28178 | Auts2 | EG667283, Nlrp4e, Vmn1r gene family | Anxa11, Plac9, D14Ertd449e, Cphx, Duxbl | Slc25a37, D930020E02Rik, Entpd4, Loxl2 | Mid1 | Mid1 | |||

Abbreviation: CNV, copy number variant.

CNVs were detected using a (A) commercial, genome-wide aCGH array and/or (B) a targeted, custom CNV array, pending on suitable probes being present. The total number of probes supporting each CNV, its estimated size and genomic location are listed together with the genes that were either contained or affected by the CN.

Figure 1.

Relative copy number (rCN) in the combined samples established by Sequenom. rCN in the combined samples was examined by Sequenom competitive quantitative PCR. The data from both sets of animals are shown with all values scaled to set a relative CN of 1 at 0. (a) Variation in CNV2 was established using three separate assays targeting the 5′ prime, central or 3′ prime region of this CNV, respectively. (b) The remaining CNVs were detected by one assay, each. CNV2–CNV6: Boxes denote positive calls for amplifications or deletions. No formal assignment of calls was performed for the highly variable loci CNV1 and CNV7. CNV, copy number variant.

Both CNV1 and CNV7 were found to be prevalent and hypervariable in both the parents and the offspring (the wide distribution of rCN for these CNVs in Figure 1 must be noted). Therefore, it was not possible to determine whether these particular CNVs in the offspring were de novo or inherited. The detailed counts for the remaining five CNVs are shown in Table 2. On the basis of these CNVs, in the combined samples, we identified a total of six de novo CNVs, in the offspring of aged sires—one offspring with a deletion in CNV2, four offspring with deletions in CNV4 and one of CNV6. The latter was a reversion of an X-linked region in a daughter of an aged sire with an expansion in this locus (Supplementary Material S4). No de novo CNVs were detected in the offspring of control sires. We estimate that the offspring of aged sires were 16 times more likely to have a de novo CNV compared with the offspring of control sires (Haldane correction applied to all counts; odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals=15.9, 2.2—undefined, mid-P-exact=0.005).

Table 2. Occurrence of CNV2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 in the combined samples.

| Parameter | n | CNV2 | CNV3 | CNV4 | CNV5 | CNV6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced paternal age group | ||||||

| Sire | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Dam | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Female offspring | 21 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Male offspring | 19 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Sum | 60 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 7 |

| Control group | ||||||

| Sire | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Dam | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Female offspring | 27 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Male offspring | 22 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Sum | 69 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Total number of animals (%) | 129 | 1 (1) | 14 (5) | 28 (22) | 8 (3) | 14 (5) |

| De novo calls | ||||||

| Advanced paternal age group | 6 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Control group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviation: CNV, copy number variant.

The number of sires, dams, male and female offspring tested in each experimental group by either array and/or Sequenom is shown (n) together with the number of those animals affected by an aberration. In addition, the total number and proportion of all animals (%) affected and the number of de novo calls for each CNV and each experimental group is detailed.

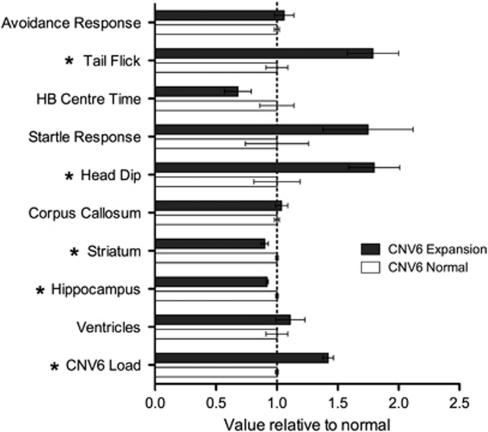

Correlation between CNV load and selected phenotypic measures

We identified significant correlates for two of the CNVs with behavioral and MRI-derived neuroanatomical phenotypes. For CNV1 (a prevalent and hypervariable locus), offspring with higher rCN had significantly more avoidance responses (R=0.489, F=8.78, df=28, P=0.006). For CNV6 (an X-linked locus) both behavioral and neuroanatomical features were significantly correlated (see Figure 2). As expected, the X-linked CNV6 expansion was only seen in female offspring. When compared with CNV-negative APA females, those with CNV6 expansion had a higher score for tail flick (a measure related to pain threshold; t(14)=4.0, P<0.001) and higher scores on head dip on the hole board test (a measure related to exploratory behavior; t(14)=2.7, P=0.02). With respect to the MRI measures, those with CNV6 expansion had smaller striatal (t (14)=3.89, P<0.01) and hippocampal volumes (t (14)=4.84, P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Normalized values on CNV6 load—MRI and behavioral measures. HB center time=proportion of time spent in center zone of the hole board arena. Avoidance response and head dip are count variables. Tail flick and HB center time are timed outcomes (in seconds). Startle response is average amplitude of response to 120 decibels. MRI outcomes include volume of the striatum, hippocampus and ventricles, and width of the corpus callosum. Statistically significant group differences by CNV6 status are shown with an asterisk. CNV, copy number variant; HB, hole board; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Bioinformatic analysis of syntenic regions in humans

Copy number variant 1 spanned 33 characterized genes on mouse chromosome 4 and their orthologs in the syntenic region of this CNV in humans on chromosome 9. Within this region, amplifications and deletions have been observed. A gene encompassed by CNV1 (Sigmar1) has been associated with alcoholism,37 schizophrenia38 and dementia.39

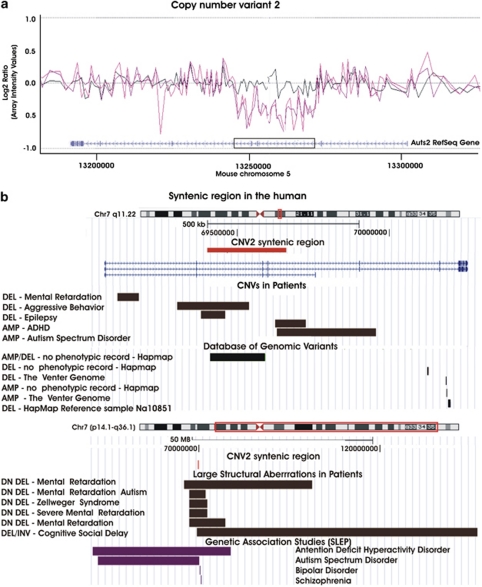

Copy number variant 2 spanned exons 3 and 4 in the mouse and the syntenic human Auts2 gene (see Figure 3). This locus has been associated with autism,40 schizophrenia,41 bipolar disorder,42 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder43 and alcoholism.44 Moreover, this gene was reported as differentially methylated in a study on patients with schizophrenia and major psychosis in schizophrenics.45 Although several small CNVs have been observed in the general population,46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 separate aberrations within this gene and overlapping with CNV2 have been reported in cases with neurodevelopmental disorders.19, 52, 53, 54 Balanced translocations disrupting Auts2 have been observed in additional cases with autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation.55 In addition, larger aberrations encompassing Auts2 have been reported in cases with mental retardation,54, 56, 57, 58 Zellweger's syndrome59 and social cognitive delay.60

Figure 3.

CNV2 details. (a) Array log(2) signal intensity ratios of the individual probes are plotted along mouse chromosome 5 and connected with a trend line based on triangular smoothening. A de novo deletion (CNV2) affecting the Auts2 gene was detected in one female offspring of an old sire. The two purple lines depict the result of a technical replicate with the animal containing the deletion. The black line visualizes the result obtained from a self-hybridization array, which was used to control for noise. The location of the CNV on the mouse genome is boxed. (b) CNV2 was aligned to the human genome using the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) together with copy variants observed in the human and genomic regions associated with neurocognitive disease. HapMap: Case from the International Hapmap Project. SLEP, Sullivan Laboratory Evidence Project; CNV, copy number variant; DEL, deletion; AMP, amplification; DN, de novo.

For CNV4, three (Anxa11, Plac9 and D14Ertd449e) of the five genes affected by this CNV mapped to human chromosome 10. One patient with schizophrenia61 and two with autism spectrum disorder54 carried aberrations <600 kb in size that also contained these genes. CNV5 mapped to a locus in human chromosome 8 that has been associated with schizophrenia in a meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies.62 An aberration containing this region was present in a patient with mental retardation.54

Both CNV6 and CNV7 affected the Mid1 gene on chromosome X. In the mouse, a pseudoautosomal boundary is situated between exons 3 and 5 of Mid1.63 The region upstream of exon 3 is specific to the X chromosome, whereas the region downstream of this exon is located on both sex chromosomes.63 The pseudoautosomal portion is highly variable within C57BL/6J.28, 64, 65 In our current study, CNV6 spanned exons 2 and 3 and is, therefore, X-linked. The two breakpoints for CNV7 were between exons 3 and 4 and ∼11 kb downstream of this gene in the pseudoautosomal region. CNV6 and CNV7 map to the same location in Mid1 in humans, where the entire gene is X linked. Genetic loss of function mutations in Mid1, has been found causative for the Opitz G/BBB syndrome, which is characterized by a varied phenotype that might include a range of midline birth defects and mental retardation.66 A patient with Opitz G/BBB syndrome and autism carried a discrete deletion of Mid1 exon 2 (contained in CNV6).67 A separate case with autism but without Opitz G/BBB syndrome carried a duplication that included the Mid1 gene from exon 2 onwards to a region ∼500 kb downstream of his gene.68

Discussion

We report, for the first time, experimental evidence indicating that the offspring of older males have an increased risk of de novo CNVs. Although the field has long appreciated that male germ cells would be at risk of more copy error mutations compared with female germ cells,69, 70 the empirical evidence has rested on the observation that particular types of paternally derived translocations seem to be more common in offspring of older men,71, 72 and studies that compared the counts of candidate point mutations in the sperm of men of different ages.73, 74 Here, we used a well-controlled mouse model to investigate the impact of paternal age on CNVs in the offspring. Although our sample size was small, we identified six de novo CNVs in this study, and all de novo CNVs were in the offspring of aged sires.

On the basis of detailed comparisons between C57BL/6J and closely related strains, Egan et al.65 estimated that de novo CNVs occurred once in every 46–139 offspring. The lack of de novo CNVs in the offspring of control animals is consistent with these estimates. In contrast, for the offspring of aged sires, we estimate that the incidence of de novo CNVs is once in every six or seven offspring. Although we cannot be certain that the de novo CNVs originated in the paternal germline, because the age of the dams was the same in the two groups, we would have expected an even distribution of maternally derived mutations in the two groups. Similarly, somatic mutations after fertilization should be equally represented in both groups. On the balance of probability, it is likely that these CNVs were derived from the male germline. Future studies could use dams and sires from different mouse strains to allocate de novo CNVs to maternal or paternal chromosomes.

With respect to the clinical relevance of our findings in humans, our mouse model detected CNVs that impact on genes previously linked to autism, schizophrenia and mental retardation. Three of the CNVs occurred in regions of prominent segmental duplication, which suggests that non-allelic homologous recombination may underlie at least some of the age-related CNVs. The two prevalent and hypervariable CNVs (CNV1 and CNV7) are of interest and potentially important for interpreting within-colony variation in this strain of mouse. However, these may be less relevant to human health outcomes as disease-related CNVs tend to be rare and ‘privileged' within pedigrees.23 It should also be noted that mechanisms other than CNVs may contribute to the association between APA and increased risk of disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism. For example, it is feasible that epigenetic changes identified in sperm from older males may also contribute to adverse health outcomes in the offspring.75

The study has several important limitations. As our study was exploratory in nature, the sample size was small, and we used readily accessible technology to assess CNVs. The use of (1) aCGH arrays with greater probe coverage, and/or deep sequencing technology and (2) larger sample sizes, would optimize more complete CNV discovery in our APA model. Unfortunately, our experimental protocols required killing animals for ex vivo MRI before the results of the CNV analysis were completed, thus we were not able to establish breeding lines from the offspring carrying APA-related de novo CNVs. Adequate numbers of CNV-bearing offspring would be required for optimal behavioral and neuroanatomical phenotyping. Furthermore, the broad range of phenotypic measures used in our standard APA screening battery involve many comparisons, inflating type I error (our results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons). As such, the phenotypic findings reported in this study should be considered exploratory in nature and require replication in well-powered samples.

As sequencing technology improves, it may also be feasible to examine the mechanism underpinning APA directly in the sperm of young versus older males. Studies based on point mutations in a candidate gene have already demonstrated the utility of this strategy in pooled sperm samples.73, 74 Furthermore, the mouse may not be the ideal species with respect to exploring human paternal age-related mutagenesis. For example, the human genome contains slightly less segmental duplication compared with the mouse (2.3 and 4.3%, respectively)76 and is enriched for different types of retrotransposal elements. As more human genomes are sequenced (especially mother-father-offspring trios), and CNVs are more accurately detected, we predict that the offspring of older fathers will carry more de novo CNVs. It will be of interest to explore the taxonomy of paternal age-related CNVs and explore whether these mutations differentially impact on neuropsychiatric health outcomes. It is feasible that these mutations could ‘decanalize' brain development and increase the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism.77

The age of parenthood is increasing in many societies,78 and thus it is feasible that the incidence of paternal-age related de novo CNVs will increase over time. Worryingly, these CNVs can be inherited and may accumulate over several generations, with some clinical phenotypes ‘breaking through' only after a critical threshold of inherited and de novo mutations have accumulated.79 In light of the clues from epidemiology linking APA to increased risk of schizophrenia and autism, and given the convergent evidence linking rare CNVs to these two disorders, the results of our study provide a parsimonious biological mechanism that may contribute to these disabling and poorly understood disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study was support by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP569528). This study makes use of data generated by the DECIPHER Consortium. A full list of centers that contributed to the generation of the data is available from http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk and through e-mail from decipher@sanger.ac.uk. Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust. Those who carried out the original analysis and collection of the data bear no responsibility for the further analysis or interpretation of these data. Dr Naomi Wray from the Queensland Institute for Medical Research assisted with the interpretation of the aCGH data. We acknowledge support from the University of Queensland Centre for Advanced Imaging for access to the animal MRI.

Author contributions. The overall design was conceived by JJM, DWE, TF-B and EW. The animal breeding, behavioral and imaging components were undertaken by CJF. SC designed the custom array. RJM conducted the Sequenom analyses and TF-B performed the microarray assays and all the assessment of CNVs. TF-B and JJM wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Hultman CM, Sandin S, Levine SZ, Lichtenstein P, Reichenberg A.Advancing paternal age and risk of autism: new evidence from a population-based study and a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies Mol Psychiatryin press (e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Malaspina D, Harlap S, Fennig S, Heiman D, Nahon D, Feldman D, et al. Advancing paternal age and the risk of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:361–367. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Messias E, Miettunen J, Alaraisanen A, Jarvelin MR, Koponen H, et al. Meta-analysis of paternal age and schizophrenia risk in male versus female offspring Schizophr Bullin press (e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frans EM, Sandin S, Reichenberg A, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N, Hultman CM. Advancing paternal age and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1034–1040. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard M, Mork A, Madsen KM, Olsen J. Paternal age and epilepsy in the offspring. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:1003–1005. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-4250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Barnett AG, Foldi C, Burne TH, Eyles DW, Buka SL, et al. Advanced paternal age is associated with impaired neurocognitive outcomes during infancy and childhood. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e40. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JL, Perry GH, Feuk L, Redon R, McCarroll SA, Altshuler DM, et al. Copy number variation: new insights in genome diversity. Genome Res. 2006;16:949–961. doi: 10.1101/gr.3677206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Troge J, Alexander J, Young J, Lundin P, et al. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, et al. Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:78–88. doi: 10.1086/431652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jiang T, Mao JH, Balmain A, Peterson L, Harris C, et al. Genomic segmental polymorphisms in inbred mouse strains. Nat Genet. 2004;36:952–954. doi: 10.1038/ng1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubert TA, Cahan P, Edwin D, Selzer RR, Richmond TA, Eis PS, et al. A high-resolution map of segmental DNA copy number variation in the mouse genome. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Shen Y, Weiss LA, Korn J, Anselm I, Bridgemohan C, et al. Microdeletion/duplication at 15q13.2q13.3 among individuals with features of autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders. J Med Genet. 2009;46:242–248. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Pagnamenta AT, Klei L, Anney R, Merico D, Regan R, et al. Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2010;466:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy SE, Makarov V, Kirov G, Addington AM, McClellan J, Yoon S, et al. Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/ng.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Scherer SW, Brzustowicz LM. Copy number variations in schizophrenia: critical review and new perspectives on concepts of genetics and disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:899–914. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09071016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Roos JL, Levy S, van Rensburg EJ, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:880–885. doi: 10.1038/ng.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Schizophrenia C Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefford HC, Muhle H, Ostertag P, von Spiczak S, Buysse K, Baker C, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation in epilepsy: novel susceptibility loci in idiopathic generalized and focal epilepsies. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig I, Mefford HC, Sharp AJ, Guipponi M, Fichera M, Franke A, et al. 15q13.3 microdeletions increase risk of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:160–162. doi: 10.1038/ng.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries BB, Pfundt R, Leisink M, Koolen DA, Vissers LE, Janssen IM, et al. Diagnostic genome profiling in mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:606–616. doi: 10.1086/491719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenstaller J, Spranger S, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Kazmierczak B, Nathrath M, Wahl D, et al. Copy-number variations measured by single-nucleotide-polymorphism oligonucleotide arrays in patients with mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:768–779. doi: 10.1086/521274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan MC, Kirov G, Owen MJ. Phenotypic variations on the theme of CNVs. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1392–1393. doi: 10.1038/ng1208-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auroux M. Decrease of learning capacity in offspring with increasing paternal age in the rat. Teratology. 1983;27:141–148. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420270202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RG, Kember RL, Mill J, Fernandes C, Schalkwyk LC, Buxbaum JD, et al. Advancing paternal age is associated with deficits in social and exploratory behaviors in the offspring: a mouse model. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Palomares S, Pertusa JF, Minarro J, Garcia-Perez MA, Hermenegildo C, Rausell F, et al. Long-term effects of delayed fatherhood in mice on postnatal development and behavioral traits of offspring. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:337–342. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.072066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldi CJ, Eyles DW, McGrath JJ, Burne TH. Advanced paternal age is associated with alterations in discrete behavioural domains and cortical neuroanatomy of C57BL/6J mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:556–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She X, Cheng Z, Zollner S, Church DM, Eichler EE. Mouse segmental duplication and copy number variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:909–914. doi: 10.1038/ng.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Williams H, Majounie E, Norton N, Glaser B, Morris HR, et al. Analysis of copy number variation using quantitative interspecies competitive PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding C, Maier E, Roscher AA, Braun A, Cantor CR. Simultaneous quantitative and allele-specific expression analysis with real competitive PCR. BMC Genet. 2004;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, K F.The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates3rd edn.Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Konneker T, Barnes T, Furberg H, Losh M, Bulik CM, Sullivan PF. A searchable database of genetic evidence for psychiatric disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:671–675. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33 (Database issue:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberger J, Bocchini CA, Scott AF, Hamosh A. McKusick's Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37 (Database issue:D793–D796. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Feuk L, Duggan GE, Khaja R, Scherer SW. Development of bioinformatics resources for display and analysis of copy number and other structural variants in the human genome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;115:205–214. doi: 10.1159/000095916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyatake R, Furukawa A, Matsushita S, Higuchi S, Suwaki H. Functional polymorphisms in the sigma1 receptor gene associated with alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa R, Hashimoto K, Tochigi M, Kawakubo Y, Marumo K, Sasaki T, et al. Association between sigma-1 receptor gene polymorphism and prefrontal hemodynamic response induced by cognitive activation in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luty AA, Kwok JB, Dobson-Stone C, Loy CT, Coupland KG, Karlstrom H, et al. Sigma nonopioid intracellular receptor 1 mutations cause frontotemporal lobar degeneration-motor neuron disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:639–649. doi: 10.1002/ana.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen-Brady K, Miller J, Matsunami N, Stevens J, Block H, Farley M, et al. A high-density SNP genome-wide linkage scan in a large autism extended pedigree. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:590–600. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Lin D, Tzeng JY, van den Oord E, Perkins D, Stroup TS, et al. Genomewide association for schizophrenia in the CATIE study: results of stage 1. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:570–584. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, et al. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K, Dempfle A, Arcos-Burgos M, Bakker SC, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage scans of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1392–1398. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann G, Coin LJ, Lourdusamy A, Charoen P, Berger KH, Stacey D, et al. Genome-wide association and genetic functional studies identify autism susceptibility candidate 2 gene (AUTS2) in the regulation of alcohol consumption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7119–7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017288108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, et al. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, Feuk L, Perry GH, Andrews TD, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills RE, Walter K, Stewart C, Handsaker RE, Chen K, Alkan C, et al. Mapping copy number variation by population-scale genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;470:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature09708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang AW, MacDonald JR, Pinto D, Wei J, Rafiq MA, Conrad DF, et al. Towards a comprehensive structural variation map of an individual human genome. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R52. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan KJ, Peckham HE, Costa GL, McLaughlin SF, Fu Y, Tsung EF, et al. Sequence and structural variation in a human genome uncovered by short-read, massively parallel ligation sequencing using two-base encoding. Genome Res. 2009;19:1527–1541. doi: 10.1101/gr.091868.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL, Walenz BP, et al. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju YS, Hong D, Kim S, Park SS, Lee S, Park H, et al. Reference-unbiased copy number variant analysis using CGH microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e190. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusco I, Medrano A, Gener B, Vilardell M, Gallastegui F, Villa O, et al. Autism-specific copy number variants further implicate the phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway and the glutamatergic synapse in the etiology of the disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1795–1804. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia J, Gai X, Xie HM, Perin JC, Geiger E, Glessner JT, et al. Rare structural variants found in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder are preferentially associated with neurodevelopmental genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DECIPHER . DECIPHERv5.1. The DECIPHER consortium, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huang XL, Zou YS, Maher TA, Newton S, Milunsky JM. A de novo balanced translocation breakpoint truncating the autism susceptibility candidate 2 (AUTS2) gene in a patient with autism. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2112–2114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer RA. Interstitial deletion of a chromosome 7 (q11.2q22.1) in a child with splithand/splitfoot malformation. Ann Genet. 1984;27:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillar PJ, Kaye CI, Ryan SG, Moore CM. Proximal 7q interstitial deletion in a severely mentally retarded and mildly abnormal infant. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:138–141. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RS, Weaver DD, Kukolich MK, Heerema NA, Palmer CG, Kawira EL, et al. Terminal and interstitial deletions of the long arm of chromosome 7: a review with five new cases. Am J Med Genet. 1984;17:437–450. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320170207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naritomi K, Hyakuna N, Suzuki Y, Orii T, Hirayama K. Zellweger syndrome and a microdeletion of the proximal long arm of chromosome 7. Hum Genet. 1988;80:201–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00702873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkaloglu B, O'Roak BJ, Louvi A, Gupta AR, Abelson JF, Morgan TM, et al. Molecular cytogenetic analysis and resequencing of contactin associated protein-like 2 in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozeva D, Kirov G, Ivanov D, Jones IR, Jones L, Green EK, et al. Rare copy number variants: a point of rarity in genetic risk for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:318–327. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MY, Levinson DF, Faraone SV, Suarez BK, DeLisi LE, Arinami T, et al. Meta-analysis of 32 genome-wide linkage studies of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:774–785. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S, Perry J, Kipling D, Ashworth A. A gene spans the pseudoautosomal boundary in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12030–12035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Zotto L, Quaderi NA, Elliott R, Lingerfelter PA, Carrel L, Valsecchi V, et al. The mouse Mid1 gene: implications for the pathogenesis of Opitz syndrome and the evolution of the mammalian pseudoautosomal region. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:489–499. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan CM, Sridhar S, Wigler M, Hall IM. Recurrent DNA copy number variation in the laboratory mouse. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1384–1389. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanella B, Russolillo G, Meroni G. MID1 mutations in patients with X-linked Opitz G/BBB syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:584–594. doi: 10.1002/humu.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TC, Allen LR, Cox LL, Hopwood B, Goodwin B, Haan E, et al. New mutations in MID1 provide support for loss of function as the cause of X-linked Opitz syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2553–2562. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.17.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian SL, Brune CW, Sudi J, Kumar RA, Liu S, Karamohamed S, et al. Novel submicroscopic chromosomal abnormalities detected in autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1111–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow JF. The origins, patterns and implications of human spontaneous mutation. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:40–47. doi: 10.1038/35049558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe X, Collins B, Allen J, Titenko-Holland N, Breneman J, van Beek M, et al. Aneuploidies and micronuclei in the germ cells of male mice of advanced age. Mutat Res. 1995;338:59–76. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(95)00012-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NS, Durkie M, Van Zyl B, Sanford R, Potts G, Youings S, et al. Parental and chromosomal origin of unbalanced de novo structural chromosome abnormalities in man. Hum Genet. 2006;119:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NS, Morris JK, Baptista J, Ng BL, Crolla JA, Jacobs PA. De novo apparently balanced translocations in man are predominantly paternal in origin and associated with a significant increase in paternal age. J Med Genet. 2010;47:112–115. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser RL, Broman KW, Schulman RL, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, Jabs EW. The paternal-age effect in Apert syndrome is due, in part, to the increased frequency of mutations in sperm. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:939–947. doi: 10.1086/378419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Rajmil O, Egozcue J, Templado C. Linear increase of structural and numerical chromosome 9 abnormalities in human sperm regarding age. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:754–759. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin MC, Brown AS, Malaspina D. Aberrant epigenetic regulation could explain the relationship of paternal age to schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1270–1273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She X, Liu G, Ventura M, Zhao S, Misceo D, Roberto R, et al. A preliminary comparative analysis of primate segmental duplications shows elevated substitution rates and a great-ape expansion of intrachromosomal duplications. Genome Res. 2006;16:576–583. doi: 10.1101/gr.4949406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JJ, Hannan AJ, Gibson G. Decanalization, brain development and risk of schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry. 2011;1:e14. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray I, Gunnell D, Davey Smith G. Advanced paternal age: how old is too old. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60:851–853. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JJ. The romance of balancing selection versus the sober alternatives: let the data rule (Commentary on Keller and Miller) Behav Brain Sci. 2006;29:417–418. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.