Abstract

Low dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) levels in the striatum are consistently reported in cocaine abusers; inter-individual variations in the degree of the decrease suggest a modulating effect of genetic makeup on vulnerability to addiction. The PER2 (Period 2) gene belongs to the clock genes family of circadian regulators; circadian oscillations of PER2 expression in the striatum was modulated by dopamine through D2Rs. Aberrant periodicity of PER2 contributes to the incidence and severity of various brain disorders, including drug addiction. Here we report a newly identified variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism in the human PER2 gene (VNTR in the third intron). We found significant differences in the VNTR alleles prevalence across ethnic groups so that the major allele (4 repeats (4R)) is over-represented in non-African population (4R homozygosity is 88%), but not in African Americans (homozygosity 51%). We also detected a biased PER2 genotype distribution among healthy controls and cocaine-addicted individuals. In African Americans, the proportion of 4R/three repeat (3R) carriers in healthy controls is much lower than that in cocaine abusers (23% vs 39%, P=0.004), whereas among non-Africans most 3R/4R heterozygotes are healthy controls (10.5% vs 2.5%, P=0.04). Analysis of striatal D2R availability measured with positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride revealed higher levels of D2R in carriers of 4R/4R genotype (P<0.01). Taken together, these results provide preliminary evidence for the role of the PER2 gene in regulating striatal D2R availability in the human brain and in vulnerability for cocaine addiction.

Keywords: cocaine addiction, dopaminergic signaling, human brain, human brain imaging, Period 2 gene

Introduction

Low striatal dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) levels have consistently been reported in cocaine abusers1, 2, 3 and animal models of addiction.4, 5 In humans, low D2R density has been associated with decreased metabolism in the orbital frontal cortex.6 It was proposed that the altered dopamine (DA) signaling may lead to compulsive drug administration and, subsequently, to cocaine addiction.6, 7, 8, 9 On the other hand, drugs of abuse, including cocaine, exert their reinforcing effects by enhancing signaling in the mesolimbic and nigrostriatal DA pathways (reviewed in ref.10), so that the chronic cocaine exposure can cause stable changes in gene transcription, mRNA translation and metabolism,11 thus further intensifying D2R loss.5

Marked differences in individual responses to both acute and chronic cocaine administration are likely to reflect an impact of individual genomic makeup that is modulated by environmental factors.12, 13 Drug addiction is highly heritable (estimated heritability is about 0.72).14 As a complex non-Mendelian disorder, it is likely influenced by many genes;14 the known candidate genes cannot, however, explain this level of heritability.15 Among the most studied candidate genes for substance-use disorders14 is the DRD2 gene. Although the individual differences in the DRD2 expression are well established,16 it is not clear as to how the level of expression is regulated. Many human studies have focused on a single genetic variant, the DRD2/ANKK1 polymorphism (reviewed in ref.17), but inconsistency of the results of those studies18, 19, 20 creates the need to identify new genetic targets that have regulatory relationships with the DRD2.

Recent results from genetics of gene expression studies have demonstrated a role of polymorphic regulatory regions located in trans to the target gene.21 Regulation in trans by the clock genes, for example, leads to circadian oscillation of the expression of the majority of the human genes, including brain genes.22 Here we developed and tested the hypothesis that the PER2 (Period 2) clock gene might contribute to the regulation of D2R expression in the brain and, as such, might be associated with cocaine addiction, based on the following lines of evidence: (1) DA release in the striatum is subject to circadian oscillation;23 (2) PER2 modulates the reinforcing effects of cocaine in laboratory animals;24 and (3) individuals suffering from substance-use disorders25, 26 have aberrant patterns of sleep and circadian rhythmicity.

In rats, the expression of clock genes and extracellular DA levels in the dorsal striatum27, 28, 29 exhibits daily oscillations. As striatal PER2 fluctuations are DA-sensitive,27 it is possible that the periodicity of DA release can mediate or be mediated by D2R–PER2 regulatory relationships.

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the circadian clockworks has been largely based on the studies of model organisms and rodents. Even though circadian rhythms are ubiquitous, unique evolution of human lineage suggests that human clock genes might have distinct genomic features. That is, colonizing the world humans experienced highly diverse effects of new environments, notably, changes in photoperiodicity and seasonal rhythmicity. Specific populations thus had developed unique adaptations to particular climate zones and environments. Circadian periodicity is entrained by temperature and day–night cycle; those environmental inputs change in association with latitude, challenging the clock. It therefore seems likely that positive selection affected clock genes in modern humans, and, as such, these genes would have sequence characteristics and genomic features absent in ancestral lineage. Intra-species clock variations have distinct geographic pattern of distribution,30 suggesting that population-specific polymorphisms can enable highly adjustable regulation pattern required for population-specific adaptations.

The PER2 locus has higher levels of inter-population genetic differentiation relative to other loci, suggesting a role for geographically restricted positive selection.31 Much lower than expected under a model of neutrality estimate of the coalescence age of the putatively selected PER2 haplogroup, and relatively low FST values of the flanking polymorphic sites in both Africans vs Europeans and Africans vs Asian comparisons,31 both indicate that the PER2 locus was affected by selection after the out-of-Africa expansion.

In humans, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the PER2 gene have been associated with abnormal circadian parameters,32 chronotypes,33 depression34 and also with enhanced alcohol intake,35 although no relationship with cocaine dependence was found in a case–control study that focused on several PER2 SNPs.36

The mutagenic potential of repeat regions is higher than that of single point mutations,37 making them more favorable for generating potentially ‘adaptable' genetic substrates. Indeed, a correlation between a PER2 repeat polymorphism (microsatellite) and latitude was reported in Drosophila melanogaster,38 where clinal distribution pattern of microsatellite alleles suggested that the latitudinal structure of this polymorphism may facilitate fine tuning of circadian oscillation. We postulated that putatively polymorphic repeat variation in the human PER2 might enable environmentally influenced transcriptional regulation in a population-specific manner. Here, we report evidence supporting this hypothesis. We identified and characterized new variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism in intron 3 of the PER2 by comparing the prevalence of the VNTR alleles among African Americans and non-Africans, and among healthy controls and cocaine abusers. We also assessed the effect of this polymorphism on striatal D2R expression using brain imaging data (obtained with positron emission tomography (PET) using the D2R–radioligand [11C]raclopride). We found an association between the PER2 genotype and striatal D2R availability, as well as significant differences in VNTR allele frequencies between cocaine abusers and healthy controls that, in combination, point out that this genetic variation can contribute to vulnerability for cocaine addiction and other disorders of behavioral control that are associated with low striatal D2R levels (such as, obesity).39

Multi-allelic genetic markers, such as the PER2 intron 3 VNTR, provide information on the evolutionary history of populations40, 41 and help to identify the loci targeted by selection.42 Previously, signals for population-specific selection acting on the PER2 gene were detected using a SNP-based analysis.31 Our VNTR-based analyses revealed significantly different patterns of PER2 alleles and genotypes across ethnic groups; this finding, along with population-specific SNPs and FST values and local recombination rate, points to the involvement of positive selection in the evolution of this gene.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic analyses

We used SERV server (http://www.igs.cnrs-mrs.fr/SERV/) to estimate repeats variability and suitability for genotyping. For assessment of the signs of selection, we used the Human Genome Diversity Panel browser (http://hgdp.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/gbrowse/HGDP/), which is based on the data from the Human Genome Diversity Panel CEPH and the Phase II HapMap.43 Population-specific SNPs were obtained using Genome Variation Server (http://gvs.gs.washington.edu/GVS/).

Participants

A population sample included 509 unrelated individuals originally recruited for different imaging studies who also agreed to participate in a genetic study approved by the IRB of Stony Brook University. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject after the study had been fully explained to them. All demographic data and clinical measures were acquired via the original imaging study. Race and ethnicity was defined by self-assignment.

DNA extraction and genotyping

DNA was extracted from the blood cells using the PAXgene kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). The following primers (forward: 5′-TTGGGTTAGAGCGGTGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-CTAGGTGTCCTTTCCTGA-3′) were used to amplify the region encompassing VNTR (>chr2: 239 184 578–239 185 009). The size of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products was established by QIAxcel system of a multi-capillary electrophoresis. Individual genotype assignment was carried out based on the PCR results, wherein the alleles were categorized as four repeat ‘4R' (333 bp product), three repeat ‘3R' (277 bp) and two repeat ‘2R' (212 bp).

PET imaging data

The [11C]raclopride values associated with the genetic samples were retrieved from the imaging data set of the BNL Brain Imaging Center for studies performed over the period 2006–2010. All PET scans used in this study were performed on a Siemens, HR+ scanner. The procedures for subjects positioning and the scanning protocols were described previously1, 2 and the imaging results have been reported.2, 6 In this study, we used regional Bmax/KD values calculated for three regions of interest: caudate, putamen and ventral striatum.

Statistical analysis

Because the genetic model for this locus is unknown, we first used four-genotype classification, where the carriers of each observed genotype formed a genotype group. That is, four genotype groups represented three common genotypes: ‘4R/4R', ‘4R/3R' and ‘3R/3R' and ‘rare', which comprised of carriers of 2R allele. PER2 genotypes were evaluated with regard to the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the OEGE software http://www.oege.org/software/hwe-mr-calc.shtml44 and popgen genetic applet http://www.husdyr.kvl.dk/htm/kc/popgen/genetik/applets/kitest.htm.

All individuals participating in the imaging study were African Americans; therefore, in exploratory analyses of imaging data, we tested potential confounding effects of sex and age. Sex differences in striatal D2R binding were not significant (t-test), but age negatively correlated with D2R availability at P<0.01 level (t-test, two-tailed) as has been reported previously.45 Fitting a general linear model showed low importance of the gender with respect to the D2R levels (P=0.342) and, as expected,45 a strong effect of age (P<0.001); hence, age was included in a model. Analysis of the relationships between the D2R brain availability and the PER2 genotypes was performed with analysis of covariance (general linear model), where a regional Bmax/KD value was treated as dependent variable, PER2 genotype as between-subjects factor and age was introduced as a covariate.

Because the regions of interest imaging data did not meet the condition of sphericity (Maunchy's test statistic P=0.008, Greenhouse–Geisser=0.815), we analyzed the three brain regions independently.

All effects are reported at three conditions: the F value (F), the degrees of freedom (d.f.) and the Sig. (P-value). Partial eta-squared (ηP2) is the measure of effect size. Effects were reported as statistically significant at P<0.05.

The statistical tests were performed using the SPSS software (version 11.5).

Results

Computational analysis of the PER2 locus: identification and characterization of a new VNTR polymorphism

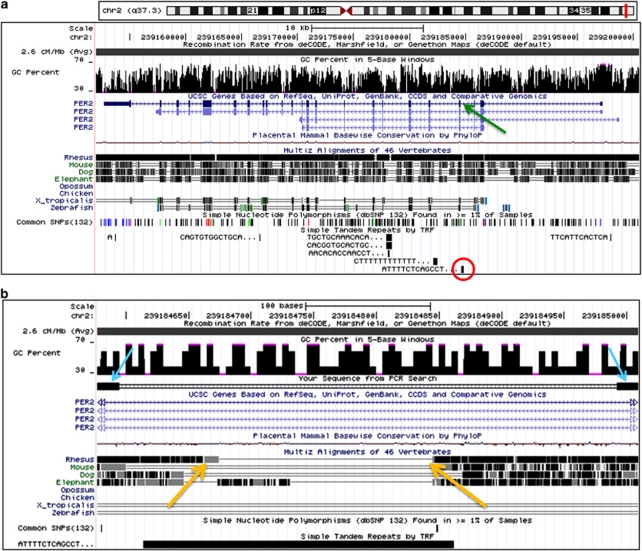

While examining the PER2 sequence, we noticed what appeared to be a 62-bp tandem repeat in intron 3 immediately preceding exon 4 (chr2q37.3; hg19—chr2: 239 184 615–239 184 862; Figure 1a). PCR amplification of genomic DNA from several humans with primers flanking this region yielded polymorphic fragments differing by approximately 62 bases. The most frequent allele (432 bp) has a length corresponding to the reference genome sequence, that is, it has 4R. In addition, we also observed alleles with 3R and 2R, which occur in homozygous and heterozygous states. Conservation tracks show that other species, including primates, lack the repeat's consensus, indicating that this allele is derived (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Location and genomic features of the human PER2 (Period 2) gene. (a, Upper panel) The locus of the chromosome 2 (q37.3) corresponding to the PER2 gene (red box). A snapshot of the PER2 locus (UCSC Genome Browser, hg19) illustrates its major genomic features, including high recombination rate (dark gray bar on the top), GC enrichment (GC % shown in full), multiple single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and tandem repeats. Polymorphic variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) (red circle) resides immediately upstream of intron 3 (green arrow). (b) The light blue arrowheads indicate positions of the primers used to amplify VNTR region. As evident from the conservation tracks, the consensus of the polymorphic tandem repeat (black bar at the bottom) is lacking in the other species, including primates (yellow arrows are pointing to boundaries of a gap in the Rhesus macaque sequence).

Distribution of VNTR allele and genotype frequencies in populations

Next, we tested the PER2 intron 3 VNTR allele frequencies in the population sample (N=509). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. In our population, the most frequent allele has 4Rs (N=820), followed by 3R (N=156) and 2R (N=42) alleles. We noticed a close similarity in genotype distribution patterns in Hispanic and Caucasian subpopulations; subsequently, we divided the sample on African Americans (N=286) and non-Africans (N=223) subsamples. Because of the low frequency of the 2R allele, the individuals who carry 2R allele(s) were assigned to the genotype group ‘rare'.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample.

| N | Male | Female | Healthy controls | Cocaine abusers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | 286 | 208 (72.7%) | 76 (26.6%) | 174 (60.8%) | 112 (39.3%) |

| Caucasians | 154 | 115 (74.7%) | 39 (25.3%) | 128 (83.1%) | 26 (16.9%) |

| Hispanics | 61 | 39 (63.9%) | 22 (36.1%) | 51 (83.6%) | 10 (16.4%) |

| Asians | 8 | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| 509 | 509 |

Values are shown in actual numbers and percentiles (within parenthesis).

The frequencies of the VNTR-based genotypes showed statistically significant differences between African Americans and non-Africans (χ2=81.1, d.f.=3, P<0.001). Minor allele frequency (3R) was 0.22 in the African Americans and only 0.056 in non-Africans. Table 2 shows the observed genotype count and population-specific genotype frequencies in percentiles.

Table 2. PER2 genotype frequencies in subpopulations.

|

Genotype |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4R/4R | 4R/3R | 3R/3R | 4R/2R | 3R/2R | 2R/2R | |

| African Americans (N=286) | 148 (51.1%) | 85 (30.1%) | 20 (7.1%) | 22 (7.8%) | 5 (1.8%) | 6 (2.1%) |

| Non-Africans (N=223) | 197 (88.2%) | 20 (8.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0 | 1 (0.4%) |

Abbreviation: PER2, Period 2.

Actual counts of genotype in subpopulations are shown along with percentiles (within parenthesis).

The PER2 genotype frequencies deviated from the values expected under HWE; we detected this deviation both by analyzing the sample as a whole and testing African-American and non-African subsamples separately. The results of HWE calculations (χ2 test) using the OEGE software (bi-allelic markers) and popgen genetic applet (multi-allelic markers) are shown in Table 3a and b, respectively.

Table 3. HWE equilibrium testing.

| Genotype |

Sample |

African Americans |

Non-Africans |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs | Exp | Obs | Exp | Obs | Exp | |

| (a) Multi-allelic model | ||||||

| 4R/4R | 346 | 331 | 144 | 138 | 202 | 199 |

| 4R/3R | 105 | 125 | 85 | 91 | 20 | 24 |

| 3R/3R | 23 | 12 | 20 | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| 4R/2R | 25 | 35 | 22 | 27 | 3 | 5 |

| 3R/2R | 5 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 2R/2R | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| χ2=56.5 | χ2=21.1 | χ2=43.3 | ||||

| (b) Bi-allelic model | ||||||

| 4R/4R | 346 | 334.05 | 144 | 138.75 | 202 | 199.75 |

| 4R/3R | 105 | 126.9 | 85 | 93.5 | 20 | 24.5 |

| 3R/3R | 23 | 12.05 | 20 | 15.75 | 3 | 0.75 |

| χ2=14.08 | χ2=2.05 | χ2=7.58 | ||||

Abbreviations: Exp, expected; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; Obs, observed.

HWE was calculated using popgen genetic applet (a, multiallelic markers) and OEGE software (b, bi-allelic markers).

A deficit of heterozygotes in relation to HWE, as it is observed in our sample, points to non-random mating or population stratification rather than to genotyping errors;46 nonetheless, we validated the PCR results by testing more than 300 samples as duplicates and triplicates, as well as tested half of the samples (about 250) using a different PCR system and protocols (not shown). Test–retest procedure confirmed genotyping assignment with a 100% accuracy. A large number of cocaine abusers in our sample (see below) suggested a possibility that bias distribution of the PER2 genotypes was due to the disease. When we tested HWE only in healthy control groups within the ethnic subsamples, we found a good agreement between the observed and the expected frequencies (African Americans: χ2=1.57, P>0.1; non-Africans: χ2=2.79, P>0.05).

Unequal distribution of VNTR genotypes in healthy controls and cocaine users

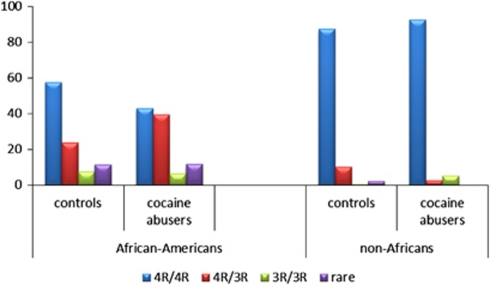

We next examined a potential effect of the VNTR polymorphism on the risk for cocaine addiction by comparing PER2 genotype frequencies in healthy controls and in cocaine abusers. Considering the differences in genotype distribution patterns, we ran separate analyses for the ethnic subsamples. Table 4 shows the absolute numbers (actual count) of the genotypes in the groups of healthy controls and cocaine abusers and Figure 2 illustrates the differences in the patterns of genotype distribution between the disease groups in two populations. The relationship between the PER2 genotype (four genotypes classification) and diagnosis was statistically significant in both subsamples (African Americans: χ2=8.63, d.f.=3, P=0.035; non-Africans: χ2=8.25, d.f.=3, P=0.041).

Table 4. PER2 genotypes distribution in healthy controls and cocaine abusers.

|

Genotype |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4R/4R | 4R/3R | 3R/3R | Rare | ||

| African Americans | |||||

| Healthy controls | 100 | 41 | 13 | 20 | 174 |

| Cocaine abusers | 48 | 44 | 7 | 13 | 112 |

| Count | 148 | 85 | 20 | 33 | 286 |

| Non-Africans | |||||

| Healthy controls | 164 | 19 | 1 | 4 | 188 |

| Cocaine abusers | 36 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 39 |

| Count | 200 | 20 | 3 | 4 | 227 |

Abbreviation: PER2, Period 2.

Figure 2.

PER2 (Period 2) genotype frequencies in controls and cocaine addicts. PER2 genotype distribution profiles (four-genotype classification) in the groups of healthy control and cocaine abusers of African Americans and non-Africans (values are shown in percentiles).

As clearly seen from Figure 2, in African Americans the proportion of 4R/3R carriers in cocaine abusers is much higher than that in healthy controls (39% vs 23%). This difference is statistically significant: χ2=8.2, d.f.=1, P=0.004. It appears that the 4R/3R genotype increases a risk for cocaine addiction, but only in the African-American population. In non-Africans, in contrast, 10.1% of healthy controls but only 2.5% of cocaine abusers carry 4R/3R genotype; thus, 4R/3R heterozygotes seem to be protected. Because most non-African individuals carry two major (4R) alleles and the frequencies of minor alleles are very low, we applied a binomial analysis comparing the 4R/4R homozygotes with the carriers of at least one minor allele (two genotypes classification). Under this partitioning, the interaction between the PER2 genotype and diagnosis (controls vs cocaine abusers) for the whole sample was significant (χ2=16, d.f.=1, P<0.001). Separate analysis of ethnic subsamples revealed, however, that the genotype effect remains significant only in the African-American sub-sample (χ2=5.6, d.f.=1, P=0.002), and does not reach a significance level in the non-African subsample (χ2=0.7, d.f.=1, P=0.4).

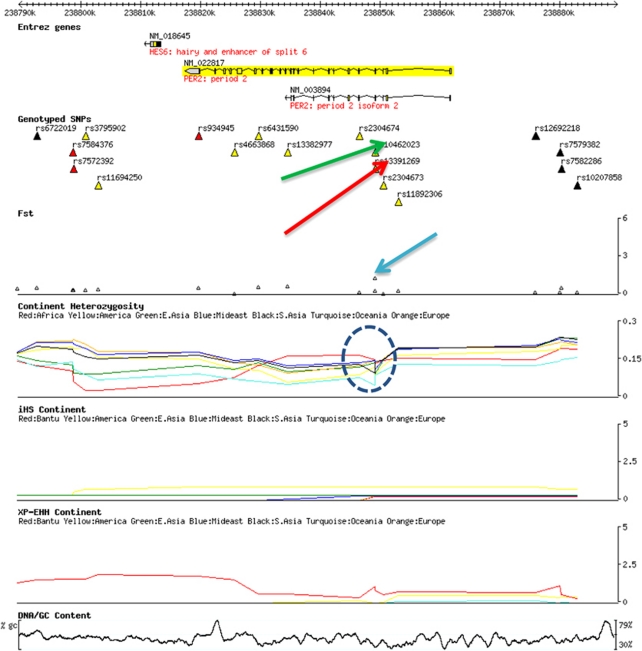

PER2 allele frequency in different populations is likely driven by geography

To explain the high divergence in VNTR-based allele frequencies between the populations in our sample, we explored the possibility that it might be due to geography-driven selection. Our inspection of the 100 kb genomic locus encompassing the PER2 revealed that the highest FST score (FST is commonly used as an estimate to measure the degree of genetic differentiation among populations47) is in the vicinity of intron 3 VNTR (Figure 3). Also, we noted an abrupt change in population heterozygosity that coincided with the VNTR region (circled).

Figure 3.

The PER2 (Period 2) region in the Human Genome Diversity Panel (HGDP) Browser. The red and green arrows point to the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the vicinity of the intron 3 variable number tandem repeat (VNTR). The blue arrow indicates a spike in FST that coincides with the intron 3 VNTR. Note an abrupt change in population heterozygosity coinciding with the VNTR region (circled).

The degree of population differentiation can be inferred from a set of population-specific SNPs classified by their physical location and functional impact. Under the assumption of neutrality, the degrees of differentiation should be the same; any deviation from this expectation could be attributed to selection.48 Indeed, the variants leading to amino-acid changes (non-synonymous mutations) are over-represented among SNPs showing high levels of FST; hence, an excess of non-synonymous SNPs in one population compared with the other points out to population-specific action of natural selection. Comparison of the population-specific SNPs in the PER2 locus (YRI vs CEU) showed an excess of non-synonymous SNPs (3 vs none) in CEU (Supplementary Table 1). This finding is quite unusual, given that the African populations show a higher level of genetic and nucleotide diversity than the European population.49, 50

Taken together, these results indicate that the PER2 locus is under selection pressure that can act discriminately on some populations and not on the others; hence, pronounced differences in PER2 allele frequencies among populations are rather expected.

PER2 genotype effect on striatal DRD2 binding potential

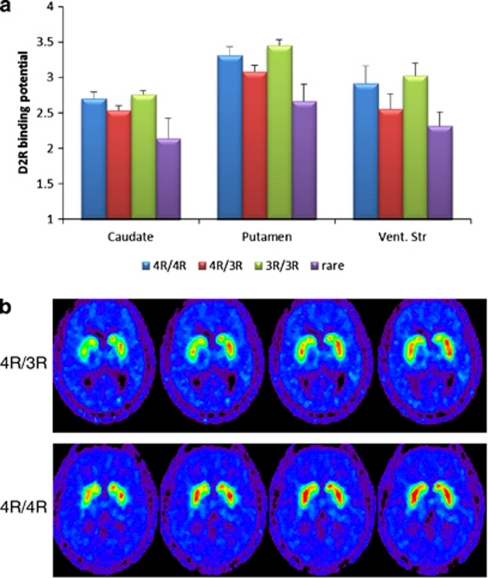

Finally, we assessed an effect of the PER2 VNTR polymorphism on brain endophenotype, using the baseline measures (non-stimulated) of striatal D2R availability or non-displaceable binding potential (BPND) for [11C]raclopride, as a proxy for brain D2R phenotype (for simplicity, herein we refer to it as D2R availability). For statistical reasons (high prevalence of the 4R/4R genotype in non-Africans diminished the power to detect an association), we included in this analysis only African-Americans individuals. The brain imaging data were available for 52 subjects (43 males and 9 females; age: 20–51 (mean: 35±8.9) years). The analysis of covariance revealed that the effect of the PER2 genotype, corrected for age, on D2R binding was significant in all striatal regions (Table 5).

Table 5. Striatal D2R binding in PER2 genotype groups.

|

PER2 genotype |

F (d.f.) | P-value | Nonicept | Observed power | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4R/4R | 4R/3R | 3R/3R | Rare | |||||

| Caudate | 2.7±0.06 | 2.54±0.06 | 2.76±0.17 | 2.14±0.2 | (7,44)=9.18 | <0.001 | 64.3 | 1 |

| 30 | 15 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| Putamen | 3.31±0.07 | 3.08±0.1 | 3.46±0.22 | 2.66±0.25 | (7,44)=8.46 | <0.001 | 59.4 | 1 |

| 30 | 15 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| Ventral striatum | 2.91±0.09 | 2.55±0.13 | 3.02±0.25 | 2.31±0.29 | (7,36)=4.13 | 0.002 | 28.9 | 0.97 |

| 24 | 13 | 3 | 4 | |||||

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; D2R, dopamine D2 receptor; d.f., degrees of freedom; PER2, Period 2.

Values of DRD2 binding in striatal regions by PER2 genotype groups are shown as model adjusted means±s.e. based on the non-transformed DRD2 binding data.

F-value, P-value (significance) and observed power (computed using α=0.05) values are from ANCOVA. η is a nonicept parameter.

Comparison of the genotype groups (four genotype classification) revealed that the 3R/4R heterozygotes' and carriers' rare allele had lower D2R binding across the brain regions relative to either 4R or 3R homozygotes (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Effect of the PER2 (Period 2) genotypes on striatal D2 receptor (D2R) binding. (a) The baseline (non-stimulated) measures of striatal D2R availability in PER2 genotype groups in three striatal regions. Y axis shows non-displaceable binding potential BP(ND) for [11C]raclopride. Bars correspond to mean D2R availability and standard errors of means in PER2 genotype groups in caudate, putamen and ventral striatum. (b) Representative PET scans of the carriers of PER2 4R/4R and 4R/3R genotypes. Normalized to the SPM template parametric images of the [11C]raclopride PET scans. Transaxial planes at the level of the striatum of individual with 4R/3R genotype (upper panel) and individual with 4R/4R genotype (bottom panel). Rainbow color scale indicates D2R availability: red shows region with the highest and blue with the lowest receptor levels. Note more red color on the planes 3, 4 and 5 of the right panel comparing with the left one, corroborating the differences in the striatal binding between the genotype groups (Table 4 and Figure 3).

Representative PET scans of male carriers of 4R/4R and 4R/3R genotypes that participated in the same study are shown in Figure 4b.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to interrogate the genomic region of the human PER2 gene for polymorphic repeats and to investigate the phenotypic effects of its putative variations on D2R expression and its association with cocaine addiction. We discovered a new VNTR polymorphism in intron 3 of the PER2 gene and found preliminary evidence that this variation is associated with striatal D2R availability, that is, heterozygous carriers of the shorter, 3R allele, or carriers of rare alleles had lower D2R availability in the striatum compared with 4R homozygotes. Comparison of the PER2 allele and genotype frequencies in healthy controls and cocaine abusers revealed significant differences in their patterns, where the shorter alleles (3R and 2R) were enriched in the group of cocaine abusers. These two findings are in line with the consistent finding of reduced striatal DRD2 availability in drug addiction.3

Observed differences between the populations in PER2 genotype by disease interactions suggest that genetic model of this polymorphism can be population-specific. It seems that effect of the 3R allele in different populations is opposing, so that African-American 3R/4R heterozygotes have higher risk for cocaine abuse, whereas in non-Africans the same allele is over-represented among healthy controls (Figure 2).

To our knowledge, this is the first report of an association between a polymorphism in a circadian gene PER2 (VNTR in intron 3) and striatal D2R availability in the human brain and with cocaine addiction. Our findings are consistent with those from prior preclinical studies,24, 51 which showed that PER2 modulates the rewarding responses to cocaine in rodents. However, they differ from the results of a prior clinical study36 that failed to detect an association between PER2 polymorphisms and drug addiction. This is not a contradiction, however, as the later study was based on SNPs analysis, whereas our analysis was focused on a new VNTR polymorphism of the PER2. Furthermore, Malison and others studied heterogeneous population, where African-American individuals were disproportionally over-represented among cocaine abusers (46%) and under-represented among healthy controls (12%); that bias may have limited their ability to detect differences. Here, we accounted for the effect of ethnicity, and to avoid such bias, analyzed African-American and non-African populations separately.

Our findings provide new insight into a mechanism by which drug-induced disruptions in DA signaling and related changes in the pattern of clock genes expression might lead to the development of pathological motivational states such as drug addiction. New evidence obtained in human populations advances our current understanding of counter-regulation of the clock genes and DA-mediated reward processes that are based on the investigation of rodents.24, 52, 53 Our results can also be interpreted in a context of pathogenicity of Parkinson's disease. In patients with Parkinson's disease, severe DA depletion in the striatum54 was observed in association with dysregulation of clock genes expression and disruptions of daily behavioral and physiological rhythms.55, 56

An earlier study by Cruciani et al.31 reported a sign of population-specific selection acting on the PER2 gene that they detected by analysis of a set of SNPs. Our findings are also consistent with population-specific positive selection and, using a new multi-allelic genetic marker, allowed us to detect statistically significant differences in frequency of PER2 alleles and heterozygosity between populations. We noted hAT-Charlie family DNA retrotransposon (MER20) residing immediately upstream of the intron 3 VNTR. Recent theoretical and experimental studies have characterized transposable elements as potentially advantageous generators of variations, which enable the action of natural selection (reviewed in ref. 57); thus, the MER20 Eutherian-specific sequence elements play a central role in rewiring the gene-regulatory landscape.58 In light of such evidence and considering that unusual genotype patterns, homozygosity and extreme values of FST are indicative of recent adaptation,59 our results support the action of positive selection on the human PER2 gene.

This study has several aims and implements different analytical tools and modalities. We predicted a new polymorphism in the PER2 gene and validated it; assessed PER2 allele distribution across ethnic groups corroborating prior evidence for geography-driven positive selection; determined differences in genotype patterns between healthy controls and cocaine users; and finally, tested a genotype effect on the levels of striatal D2R availability—a hallmark for addiction vulnerability. This approach is different from traditionally more focused studies, but we believe that our characterization of a new polymorphism is comprehensive and informative. Moreover, previous preclinical data obtained on animal models are consistent with our findings, supporting their reliability.

Study limitations

We want to emphasize that our analysis was not aimed to establish causative relationships between the PER2 and the D2R, as this would require a different experimental design.

Our population sample is ethnically heterogeneous, rather than include carefully matched cases and controls, it comprises participants from different brain imaging studies performed in our laboratory; it does, however, adequately represent the diverse population of Long Island, NY, USA.

Because of the relatively small sample size of our imaging study (as is the case for most imaging genetic studies), we consider our finding of an association between variations in the PER2 gene and brain D2R availability as preliminary and in need of replication.

We did not include in our analysis traditional markers for the PER2 locus, as a prior study showed lack of an association with cocaine addiction.36

And lastly, considering that D2R availability is influenced by environmental exposures including drugs,60 we did not expect that the link between striatal D2R availability and cocaine addiction could be fully explained by PER2 genotype.

In summary, here we identified a new VNTR polymorphism in the PER2 gene (third intron) and showed that the PER2 variances have different prevalence across ethnic groups. We detected a link between the polymorphism and D2R brain levels and significant differences in VNTR allele frequencies between CA and HC that, in combination, point out that this genetic variation can contribute to vulnerability for cocaine addiction and, perhaps, other disorders associated with low striatal D2R levels. These findings broaden our understanding of the complex networks that regulate brain dopaminergic transmission, by considering counter-regulation between the circadian clock and D2R-mediated dopamine signaling.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grants KO1 DA025280 (to ES) and R01DA023579 (to RZG). We are grateful to BNL Center for Translational Neuroimaging team for PET operation, to Dr Frank Telang, RNs Barbara Hubbard and Millard Jayne for collecting blood samples and to Karen Apelskog-Torres, AA, for protocol coordination. We also thank the individuals who volunteered to participate in this study.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wolf AP, Schlyer D, Shiue CY, Alpert R, et al. Effects of chronic cocaine abuse on postsynaptic dopamine receptors. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:719–724. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, et al. Prediction of reinforcing responses to psychostimulants in humans by brain dopamine D2 receptor levels. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1440–1443. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D. Addiction circuitry in the human brain. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Flores G, Wood GK, Barbeau D, Quirion R, Srivastava LK. Lewis and Fischer rats: a comparison of dopamine transporter and receptors levels. Brain Res. 1998;814:34–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Laane K, et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science (New York, NY) 2007;315:1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Schlyer DJ, et al. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse (New York, NY) 1993;14:169–177. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:318–325. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, London ED, Poldrack RA, Farahi J, Nacca A, Monterosso JR, et al. Striatal dopamine d2/d3 receptor availability is reduced in methamphetamine dependence and is linked to impulsivity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14734–14740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3765-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Telang F. Addiction: beyond dopamine reward circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15037–15042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010654108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Roles for nigrostriatal—not just mesocorticolimbic—dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, Im HI, Veno MT, Fowler CD, Min A, Intrator A, et al. Argonaute 2 in dopamine 2 receptor-expressing neurons regulates cocaine addiction. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1843–1851. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kam EL, Ellenbroek BA, Cools AR. Gene–environment interactions determine the individual variability in cocaine self-administration. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alia-Klein N, Parvaz MA, Woicik PA, Konova AB, Maloney T, Shumay E, et al. Gene × disease interaction on orbitofrontal gray matter in cocaine addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:283–294. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D, Oroszi G, Ducci F. The genetics of addictions: uncovering the genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:521–532. doi: 10.1038/nrg1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Li TK. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of behaviour gone awry. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nrn1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer RA, Wang D, Papp AC, Smith RM, Duque L, Mash DC, et al. Intronic polymorphisms affecting alternative splicing of human dopamine D2 receptor are associated with cocaine abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:753–762. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble EP. D2 dopamine receptor gene in psychiatric and neurologic disorders and its phenotypes. Am J Med Genet B. 2003;116B:103–125. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohoff FW, Bloch PJ, Hodge R, Nall AH, Ferraro TN, Kampman KM, et al. Association analysis between polymorphisms in the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and dopamine transporter (DAT1) genes with cocaine dependence. Neurosci Lett. 2010;473:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Castillo N, Ribases M, Roncero C, Casas M, Gonzalvo B, Cormand B. Association study between the DAT1, DBH and DRD2 genes and cocaine dependence in a Spanish sample. Psychiatric Genet. 2010;20:317–320. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833b6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballon N, Leroy S, Roy C, Bourdel MC, Olie JP, Charles-Nicolas A, et al. Polymorphisms TaqI A of the DRD2, BalI of the DRD3, exon III repeat of the DRD4, and 3′ UTR VNTR of the DAT: association with childhood ADHD in male African-Caribbean cocaine dependents. Am J Med Genet B. 2007;144B:1034–1041. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung VG, Spielman RS, Ewens KG, Weber TM, Morley M, Burdick JT. Mapping determinants of human gene expression by regional and genome-wide association. Nature. 2005;437:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/nature04244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran S, Almon RR, DuBois DC, Jusko WJ. Circadian rhythms in gene expression: relationship to physiology, disease, drug disposition and drug action. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda TR, de Prado BM, Prieto D, Mora F. Circadian rhythms of dopamine, glutamate and GABA in the striatum and nucleus accumbens of the awake rat: modulation by light. J Pineal Res. 2004;36:177–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-079x.2003.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abarca C, Albrecht U, Spanagel R. Cocaine sensitization and reward are under the influence of circadian genes and rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9026–9030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142039099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowatch RA, Schnoll SS, Knisely JS, Green D, Elswick RK. Electroencephalographic sleep and mood during cocaine withdrawal. J Addict Dis. 1992;11:21–45. doi: 10.1300/J069v11n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PT, Pace-Schott EF, Sahul ZH, Coric V, Stickgold R, Malison RT. Sleep architecture, cocaine and visual learning. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2008;103:1344–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood S, Cassidy P, Cossette MP, Weigl Y, Verwey M, Robinson B, et al. Endogenous dopamine regulates the rhythm of expression of the clock protein PER2 in the rat dorsal striatum via daily activation of D2 dopamine receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14046–14058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2128-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbesi M, Yildiz S, Dirim Arslan A, Sharma R, Manev H, Uz T. Dopamine receptor-mediated regulation of neuronal ‘clock' gene expression. Neuroscience. 2009;158:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahar S, Zocchi L, Kinoshita C, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. Regulation of BMAL1 protein stability and circadian function by GSK3beta-mediated phosphorylation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou CP, Peixoto AA, Costa R. A cline in the Drosophila melanogaster period gene in Australia: neither down nor under. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:1649–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruciani F, Trombetta B, Labuda D, Modiano D, Torroni A, Costa R, et al. Genetic diversity patterns at the human clock gene period 2 are suggestive of population-specific positive selection. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1526–1534. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Schantz M. Phenotypic effects of genetic variability in human clock genes on circadian and sleep parameters. J Genet. 2008;87:513–519. doi: 10.1007/s12041-008-0074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpen JD, von Schantz M, Smits M, Skene DJ, Archer SN. A silent polymorphism in the PER1 gene associates with extreme diurnal preference in humans. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:1122–1125. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0060-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavebratt C, Sjoholm LK, Partonen T, Schalling M, Forsell Y. PER2 variation is associated with depression vulnerability. Am J Med Genet B. 2010;153B:570–581. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuferov V, Bart G, Kreek MJ. Clock reset for alcoholism. Nat Med. 2005;11:23–24. doi: 10.1038/nm0105-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malison RT, Kranzler HR, Yang BZ, Gelernter J. Human clock, PER1 and PER2 polymorphisms: lack of association with cocaine dependence susceptibility and cocaine-induced paranoia. Psychiatric Genet. 2006;16:245–249. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000242198.59020.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemayel R, Vinces MD, Legendre M, Verstrepen KJ. Variable tandem repeats accelerate evolution of coding and regulatory sequences. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:445–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-072610-155046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou CP, Peixoto AA, Sandrelli F, Costa R, Tauber E. Clines in clock genes: fine-tuning circadian rhythms to the environment. Trends Genet. 2008;24:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Baler R.Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction Curr Top Behav Neurosciadvance online publication 21 October 2011 [e-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cole SM, Long JC. A coalescent simulation of marker selection strategy for candidate gene association studies. Am J Med Genet B. 2008;147B:86–93. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shichi D, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, Inoko H, Naruse TK, Kimura A. Complex divergence at a microsatellite marker C1_2_5 in the lineage of HLA-Cw/-B haplotype. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:224–229. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinan A, Reich D. Human population differentiation is strongly correlated with local recombination rate. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell JK, Coop G, Novembre J, Kudaravalli S, Li JZ, Absher D, et al. Signals of recent positive selection in a worldwide sample of human populations. Genome Res. 2009;19:826–837. doi: 10.1101/gr.087577.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day IN. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for Mendelian randomization studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:505–514. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, MacGregor RR, et al. Measuring age-related changes in dopamine D2 receptors with 11C-raclopride and 18F-N-methylspiroperidol. Psychiatry Res. 1996;67:11–16. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(96)02809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman K, Williams SM.Calculation and use of the Hardy–Weinberg model in association studiesIn: Haines JL et al. (eds.).Current Protocols in Human Genetics57:1.18.1-1.18.11.© 2008 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holsinger KE, Weir BS. Genetics in geographically structured populations: defining, estimating and interpreting F(ST) Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrg2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Quintana-Murci L. From evolutionary genetics to human immunology: how selection shapes host defence genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:17–30. doi: 10.1038/nrg2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich JE, Hahn MW. Disentangling the effects of demography and selection in human history. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:63–73. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldin MF, Pasaniuc B, Price AL. New approaches to disease mapping in admixed populations. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:523–528. doi: 10.1038/nrg3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BH, McDearmon EL, Panda S, Hayes KR, Zhang J, Andrews JL, et al. Circadian and CLOCK-controlled regulation of the mouse transcriptome and cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3342–3347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Nestler EJ, Zachariou V. Regulation of gene expression by chronic morphine and morphine withdrawal in the locus coeruleus and ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6005–6015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0062-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roybal K, Theobold D, Graham A, DiNieri JA, Russo SJ, Krishnan V, et al. Mania-like behavior induced by disruption of CLOCK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6406–6411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, Wang Z, Ding J, An X, Ingham CA, Shering AF, et al. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:251–259. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruguerolle B, Simon N. Biologic rhythms and Parkinson's disease: a chronopharmacologic approach to considering fluctuations in function. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25:194–201. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Liu S, Sothern RB, Xu S, Chan P. Expression of clock genes Per1 and Bmal1 in total leukocytes in health and Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:550–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver KR, Greene WK. Transposable elements: powerful facilitators of evolution. BioEssays. 2009;31:703–714. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch VJ, Leclerc RD, May G, Wagner GP. Transposon-mediated rewiring of gene regulatory networks contributed to the evolution of pregnancy in mammals. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1154–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawks J, Wang ET, Cochran GM, Harpending HC, Moyzis RK. Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20753–20758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707650104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty JF, Shi XD, Schwendt M, Saylor A, Toda S. Regulation of psychostimulant-induced signaling and gene expression in the striatum. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1440–1449. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.