Abstract

Abnormal trajectory of brain development has been suggested by previous structural magnetic resonance imaging and head circumference findings in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs); however, the neurochemical backgrounds remain unclear. To elucidate neurochemical processes underlying aberrant brain growth in ASD, we conducted a comprehensive literature search and a meta-analysis of 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) studies in ASD. From the 22 articles identified as satisfying the criteria, means and s.d. of measure of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), creatine, choline-containing compounds, myo-Inositol and glutamate+glutamine in frontal, temporal, parietal, amygdala-hippocampus complex, thalamus and cerebellum were extracted. Random effect model analyses showed significantly lower NAA levels in all the examined brain regions but cerebellum in ASD children compared with typically developed children (n=1295 at the maximum in frontal, P<0.05 Bonferroni-corrected), although there was no significant difference in metabolite levels in adulthood. Meta-regression analysis further revealed that the effect size of lower frontal NAA levels linearly declined with older mean age in ASD (n=844, P<0.05 Bonferroni-corrected). The significance of all frontal NAA findings was preserved after considering between-study heterogeneities (P<0.05 Bonferroni-corrected). This first meta-analysis of 1H-MRS studies in ASD demonstrated robust developmental changes in the degree of abnormality in NAA levels, especially in frontal lobes of ASD. Previously reported larger-than-normal brain size in ASD children and the coincident lower-than-normal NAA levels suggest that early transient brain expansion in ASD is mainly caused by an increase in non-neuron tissues, such as glial cell proliferation.

Keywords: Asperger disorder, autistic disorder, human, neuroimaging, pervasive developmental disorder, systematic review

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a representative neurodevelopmental disorder that is behaviorally defined by deficits in social reciprocity, impaired verbal communication, and restrictive and repetitive behavior.1, 2 In the background of such atypical behavioral development, previous studies have suggested the existence of atypical brain development in ASD that overall brain size was slightly reduced at birth, dramatically increased within the first year of life, but then gradually plateaued into adulthood.3, 4, 5 However, brain size studies cannot provide tissue neurochemical information. Although post-mortem studies demonstrated cytoarchitectonic abnormalities, aberrant minicolumnar organizations and microglial activations in brains of autistic individuals,6 post-mortem studies lack information about the trajectory of brain development. Therefore, the neural mechanisms explaining the aberrant trajectory of brain growth in ASD are yet to be elucidated, although several hypotheses such as excess neuron number have been proposed.6, 7

1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) is a noninvasive neuroimaging technique that estimates specific chemical metabolite measures in vivo.8 Previous studies have used 1H-MRS to quantify glutamine/glutamate (referred to collectively as ‘Glx'); N-acetylaspartate (NAA), a marker of neuronal density and activity;9 choline-containing compounds (Cho), a measure primarily reflecting the constituents of cell membranes;10 creatine and phosphocreatine (Cre), a measure of cellular energy metabolism;10 and myo-Inositol (mI), a major osmolite, precursor for phosphoinositides involved in the second messenger system.11 Previous 1H-MRS findings have yielded some inconsistency such as decreased12, 13, 14 or no difference or increased NAA measure in ASD people compared with typically developed (TD) individuals.15, 16, 17, 18 The statistical power of each single previous 1H-MRS study is relatively small, and previous studies have not corrected for multiple comparisons. As brain structural studies show an aberrant trajectory of neurodevelopment, it was reasonable to predict that the degree of neurochemical abnormalities indexed by 1H-MRS may also change according to developmental stages in ASD. However, to date only one longitudinal 1H-MRS study focusing on lactate level has been reported.19 Therefore, performing a meta-analysis is one possible solution to realize sufficient statistical power for making conclusion about the neurochemical abnormality of autistic brain and is currently the only way to examine age-related change of 1H-MRS abnormality of autistic brain.

To our knowledge, neither a systematic review nor a meta-analysis of 1H-MRS studies in people with ASD has been reported previously. The current systematic review and meta-analysis were designed to test the hypothesis that the degree of abnormalities in metabolite levels measured with 1H-MRS would change from childhood to adulthood. Concretely, in case that autistic early brain expansion is mainly caused by increase in neuronal tissue, transient increase in NAA level would be found during childhood but it would not be found in adulthood. On the other hand, if increase in non-neuronal tissue mainly contributes to early brain expansion, NAA level would be remained at normal or even on a decline in childhood but in adulthood.

Materials and methods

Data sources

1H-MRS studies that examined metabolite measures in the brains of individuals with ASD and TD control subjects were obtained through the computerized databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE and Web of Science. The search terms used in the systematic screening were autism, autistic, ASD, Asperger's, developmental disorder, pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) and mental development, which were also combined with magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MRS. Titles and abstracts of studies were examined to check whether or not they could be included. Reference lists of included articles were also examined to search additional studies to be included.

Selection of study

Studies were included if (1) they were brain 1H-MRS studies published between 1980 and December 2010, (2) they examined people with ASD compared with a TD control group and (3) they reported sufficient data to obtain significant effect sizes; means, s.d. and numbers of participants. The literature search was performed without language restriction. If they did not report sufficient data, we emailed the corresponding and then the last author to obtain them. In cases where neither of them responded, we excluded the study. Two reviewers (YA and HY) performed study screenings independently.

Data extraction

To perform the meta-analyses, we defined a standardized mean difference as the effect size statistic Cohen's d, which is calculated as the difference between the mean of the experiment group and the mean of the comparison group divided by the pooled s.d. In the current meta-analyses, mean measure of NAA, Cre, Cho, mI and Glx in autistic individuals was subtracted from those in TD groups in each volume of interest (VOI) respectively, and divided by the pooled s.d. of both. Data were separated by the mean age of participants to examine the hypothesis the degree of metabolite measure abnormality would change from childhood to adulthood. When the mean age of participants was >20, the study was included in the meta-analysis in adulthood.15, 18, 20, 21 In a study reporting the age range as from 3 to 5 years with no description of the mean age of participants, we considered the participants to have a mean age of 4 years.22 In cases of studies reporting more than two measures of metabolites, we determined the priority for extraction as absolute measure then ratio to Cre. Two reviewers (YA and HY) performed all the data extraction and computation of effect size independently to minimize errors. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines23 were followed in the study.

Identification of brain regions

Our hypothesis focused on the developmental aspect of autistic brain pathology, we classified the sub-regions into frontal, amygdala-hippocampus complex (AHC), temporal, parietal, cerebellum and thalamus, in line with the similarity of developmental background within each sub-region.24 In the case of a study reporting measures from more than one sub-region in one area (for example, anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), these were assigned to the appropriate meta-analysis sub-group (that is, frontal lobe) as two (or more) independent data sets regardless of tissue type, such as gray matter, white matter or both. VOIs in the medial temporal lobe that included the hippocampus or amygdala region were included into AHC sub-group.13, 22, 25 VOIs in the intraparietal sulcus20 and temporoparietal junction20 were assigned to the parietal lobe, while that in the insula14 was assigned to the temporal lobe. To ensure the meta-analysis was sufficiently powered, brain region measures were included if there were two or more studies reporting more than three VOIs in total. VOIs in TD control subjects who were compared with more than two ASD groups were identified25, 26 and divided into the appropriate number of comparison sub-groups to avoid duplicate counting.

Meta-analysis

All meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager ((RevMan) [Computer program], Version 5.1, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011) from the Cochrane collaboration. A random effect model was adapted for the current meta-analysis to control potential heterogeneity such as variation in location of VOI, implementation of tissue segmentation within VOIs, single- vs multi-voxel spectroscopy, echo time, volume of VOI and types of metabolites measure. Cohen's d was calculated and used as effect sizes. As the differences in metabolite levels in ASD compared with TD subjects were predicted to differ between childhood and adulthood, the comparison was examined separately in childhood and adulthood. We employed conservative definitions of significance level determined using Bonferroni corrections, with P<0.0022 in childhood (=0.05/23 included metabolites in six regions) and P<0.0033 in adulthood (=0.05/15 included metabolites in four regions; Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

The robustness of significant findings from meta-analysis was further tested by sensitivity analysis in specified sub-groups excluding studies with potential confounds. These potential confounds included comorbid epilepsy, medication, presence of mental retardation, field strength of MR scanner, types of MRS measures, segmentation within VOIs and diagnostic tools. The significance level was defined as P<0.0014 (=0.05/35 comparisons (7 potential confounds × 5 regions)).

Meta-regression

To test the hypothesis that neurochemical abnormalities would change with age, we performed meta-regression analyses in the combined children–adult sample to examine the relation between participants' mean age and Cohen's d for the NAA levels in the frontal lobe, parietal lobe and AHC in which the meta-analysis revealed significant differences between ASD and TD individuals in childhood or adulthood, with sufficient sample sizes to test meta-regression (n>10).27 The regression was examined using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The level of statistical significance was defined, by applying the Bonferroni correction, as P<0.012 (=0.05/4 areas).

The current meta-analyses included studies with considerable heterogeneities; such as presence of mental retardation, medication, types of MRS measures, employment of segmentation within the VOI, volume of VOI and comorbid epilepsy (for example, absolute measure or ratio to Cre). To investigate the influence of these potential modifiers, we performed meta-regression analyses for the metabolite measures in which the current meta-analyses showed significant difference between subjects with ASD and TD. The meta-regressions were examined in the childhood and adulthood combined sample to examine in a sufficient number of data sets.27 The significance level was set at P<0.05 to strictly assess the effect of heterogeneity.

Assessing between-study heterogeneity

The Cochran Q and I2 statistics were employed to examine between-study heterogeneity. The significance level was defined as P<0.10 to conclude the studies were heterogeneous.28

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed qualitatively by visual inspection of funnel plots and quantitatively by linear regression analysis for each group and each brain region. Based on previous literature,27 this calculation was tested with data sets of at least 10.

Data synthesis

Twenty-three demographic, clinical and methodological variants, including the number of participants, number of male participants, mean age, range of age, intelligence quotient range, diagnostic criteria or tools, pharmacological status, presence of comorbid epilepsy, sequence for MRS acquisition, utilization of segmentation within VOIs, strength of magnetic field (Tesla), echo time (TE), repetition time (TR), types of MRS measurements (absolute measure or ratio to Cre), type of metabolites reported, location of VOI, size of VOI, and main results of the study were extracted, as shown in Table 1. Total number of participants, studies and VOIs, and mean difference, 95% confidence interval, P-value, I2 score and significance of linear regression analysis of symmetric property of funnel plots calculated from each meta-analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Summary of included articles.

| Study |

Demographic character |

Methodological character |

Results |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | Mean age years | Nb | IQc | Diagnostic tools | Medication/ comorbidity | MRS sequence/ segmentation | Tesla/TE/ TR (ms) | Types of MRS measures | NAA | Cre | Cho | mI | Glx | VOI location | VOI size (ml) | Compared with TD | |

| (males) | (range) | ||||||||||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||||

| Chugani et al28 | 9 (8) | 5.7 (3–12) | 5 | NA | DSM-IV | NA NA | STEAM Undone | 1.5 30/2000 | Absolute | + | − | − | − | − | FL | NA | NS |

| TL | NA | ||||||||||||||||

| CL | NA | NAA↓ | |||||||||||||||

| DeVito et al.12 | 26 (26) | 9.8 (6–17) | 29 | ≧70 | DSM-IV ADIR ADOS-G | Medicated No comorbidity | SEMS Done | 3 135/1800 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | + | lt. FL | 1.2 | NAA, Glx ↓ |

| rt. FL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. TL | 1.2 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| rt. TL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. OL | 1.2 | NAA, Glx ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. OL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. CL | 1.2 | Glx↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. CL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. CL | 1.2 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| rt. CL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Endo et al.25 | 38 (32) | 12.9 (6–20) | 16 | 89.9 (mean) | DSM-IV | No medication No comorbidity | PROBE/SV Done | 1.5 35/2000 | Ratio | + | − | + | − | − | rt. MT | 8 | NAA/Cre ↓ |

| rt. MPFC | 8 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| CV | 8 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| Fayed and Modrego29 | 21 (18) | 7.3 NA | 12 | NA | DSM-IV | Drug naïve NA | PRESS Undone | 1.5 30/2500 | Ratio | + | − | + | + | − | lt. CS | 8 | NS |

| Friedman et al.30 | 45 (38) | 3.95 (3.2–4.5) | 13 | NA | ADIR ADOS-G | Drug naïve No comorbidity | NA Done | 1.5 20/2000 272/2000 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | − | rt. FL | 1 | NS |

| lt. FL | 1 | NAA, Cre ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. cingulate | 1 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. cingulate | 1 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. caudate | 1 | mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. caudate | 1 | mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. putamen | 1 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| lt. putamen | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. TH | 1 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. TH | 1 | Cre ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. insula | 1 | mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. insula | 1 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| rt. TL | 1 | NAA, Cho ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. TL | 1 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| rt. MT | 1 | Cho ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. MT | 1 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| at. callosum | 1 | Cre, mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| pt. callosum | 1 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| rt. PL | 1 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. PL | 1 | Cre, mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| OL | 1 | mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| Fujii et al.31 | 31 (25) | 6.1 (2–13) | 28 | NA | DSM-IV | NA NA | PRESS Undone | 1.5 135/1300 | Absolute Ratio | + | + | + | − | − | ACC | 4.5 | NAA/Cre ↓ |

| lt. DLPFC | 3.4 | NAA/Cre ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. DLPFC | 3.4 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| Gabis et al.26 | 13 (10) | 10 (7–16) | 8 | ≧80 | DSM-IV-TR | Drug naïve No comorbidity | PRESS Undone | 1.5 40/2000 | Ratio | + | − | + | + | − | rt. AHC | 4.1 | NAA/Cre↓, mI/Cre↑ |

| lt. AHC | 4.1 | NAA/Cre↓, Cho/Cre↑, mI/Cre↑ | |||||||||||||||

| CL | 8 | Cho/Cre↑, mI/Cre↑ | |||||||||||||||

| Harada et al.32 | 12 NA | 5.2 (2–11) | 10 | NA | DSM-IV | NA NA | STEAM Done | 3 15/5000 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | + | lt. FL | 9 | NS |

| lt. lenticular | 9 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hardan et al.,39 | 18 (18) | 11.9 (8–15) | 16 | >70 | ADI-R ADOS | NA No comorbidity | STEAM Done | 1.5 20/1600 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | + | rt. TH | 5.8 | NS |

| lt. TH | 5.7 | Cre, Cho, NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| Hashimoto et al.33 | 28 (20) | 5.6 (3–12) | 25 | 59.8(mean) | DSM-III-R | NA 6: epilepsy | STEAM Undone | 1.5 270/1500 | Ratio | + | − | + | − | − | rt. PL | 8∼27 | NS |

| Hisaoka et al.34 | 55 (47) | 5.8 (2–21) | 51 | NA | ICD-10 | NA NA | PRESS Undone | 1.5 135/1300 | Absolute | + | − | − | − | − | lt. FL | 3.4 | NS |

| rt. FL | 3.4 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. PL | 3.4 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. PL | 3.4 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. TL | 3.4 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. TL | 3.4 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| CG | 5.65 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| Levitt et al.14 | 22 (18) | 10.4 (5.4–15.7) | 20 | 95.0 (mean) | DSM-IV ADIR ADOS | Medicated No comorbidity | NA Done | 1.5 272/2300 | Absolute | + | + | + | − | − | lt. FL | 1.2 | NS |

| rt. FL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. PL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. PL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. OL | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. OL | 1.2 | Cre ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. inf AC | 1.2 | Cho ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. inf AC | 1.2 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| lt. sup AC | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. sup AC | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. caudate head | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. caudate head | 1.2 | Cho, Cre ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. caudate body | 1.2 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. caudate body | 1.2 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| lt. putamen | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. putamen | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. TH | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt.TH | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. FL | 1.2 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. FL | 1.2 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| lt. PL | 1.2 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. PL | 1.2 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| Mori et al.61 | 29 (22) | 8 (median) (5–15) | 19 | NA | DSM-IV | NA 8:epilepsy | STEAM Undone | 1.5 18/5000 | Ratio | + | − | + | − | − | lt. MT | 4.3∼6 | NS |

| rt. MT | 4.3∼6 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| lt. CH | 4.3∼6 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| Mori 22 | 70 (56) | NA (3–5) | 18 | NA | DSM-IV | NA 5 epilepsy | MEGA- PRESS Undone | 3 68/1500 15/5000 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | + | ACC | 12 | mI ↓ |

| O'Brein et al.16 | 12 (11) | 13 NA | 10 | 98 (mean) | ICD-10 ADI, ADOS | No medication No comorbidity | PRESS Done | 1.5 35/3000 | Absolute Ratio | + | + | + | + | − | rt. AHC | 6 | NAA ↑ |

| Otsuka et al.35 | 27 (21) | NA (2–18) | 10 | NA | ICD-10 | NA NA | STEAM Undone | 1.5 18/5000 | Absolute | + | + | + | – | – | rt. AHC | 6 | NAA ↓ |

| lt. CH | 6 | NAA ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| Vasconcelos et al.36 | 10 (10) | 9.5 (median) NA | 10 | NA | DSM-IV | Medicated No comorbidity | Press Undone | 1.5 30/1500 | Absolute Ratio | + | + | + | + | − | AC | 8 | NS |

| lt. FL | 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. striatum | 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. CL | 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Adults | |||||||||||||||||

| Bernardi et al.20 | 14 (12) | 29.2 (21–50) | 14 | >80 | DSM-IV ADIR ADOS-G | No medication No comorbidity | PRESS Undone | 3 30/2000 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | + | lt. TH | 0.5625 | NS |

| rt. TH | 0.5625 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. TPJ | 0.5625 | mI ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| rt. TPJ | 0.5625 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| lt. IPS | 0.5625 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. IPS | 0.5625 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. ACC | 0.5625 | ||||||||||||||||

| rt. ACC | 0.5625 | Glx ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| Kleinhans et al.37 | 13 (13) | 24.5 (15–44) | 13 | >70 | DSM-IV ADIR ADOS | Medicated 1:Epilepsy | PRESS Undone | 1.5 35/3000 | Absolute | + | + | + | − | − | lt. FL | 2.7 | NAA ↓ |

| rt. CH | 2.7 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| CV | 2.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| lt. PL | 2.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| OL | 2.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Kleinhans et al.38 | 20 (18) | 23.57 NA | 19 | ⩾80 | DSM-IV ADIR ADOS | NA NA | PRESS Done | 1.5 30/2000 | Absolute Ratio | + | + | + | + | − | rt. AHC | 3.4 | NS |

| lt. AHC | 3.4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Murphy et al.15 | 14 (14) | 30 NA | 18 | 97 (mean) | ICD-10 ADIR | Had medication No comorbidity | PRESS Done | 1.5 136/2000 | Absolute | + | + | + | − | − | rt. MPFC | 8.5 | NAA, Cre, Cho ↑ |

| rt. MPL | 8.5 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| O'Brein et al.16 | 10 (7) | 35 NA | 12 | 105 (mean) | ICD-10 ADI, ADOS | No medication No comorbidity | PRESS Done | 1.5 35/3000 | Absolute Ratio | + | + | + | + | − | rt. AHC | 6 | NS |

| Oner et al.18 | 14 (14) | 24.3 (17–38) | 21 | >70 | DSM-IV | Medicated No comorbidity | PRESS Undone | 1.5 270/1500 | Ratio | + | − | + | − | − | rt. ACC | 1 | NAA/Cho ↑ |

| rt. DLPFC | 1 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| Page et al.17 | 25 (20) | 35.6NA | 21 | >70 | ICD-10 ADIR (72%) | Drug naïve No comorbidity | PRESS Done | 1.5 35/3000 | Absolute | + | + | + | + | + | rt. AHC | 6 | Cre, Glx ↑ |

| rt. PL | 8 | NS | |||||||||||||||

| Suzuki et al.21 | 12 (12) | 22 (18–25) | 12 | >70 | ADIR ADOS | Drug naïve No comorbidity | PRESS Done | 1.5 144/1500 | Absolute | + | + | + | − | − | lt. AHC rt. CH | 6 8 | Cho, Cre ↑ NAA ↓ |

Abbreviations: AC, anterior cingulate; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; ADIR, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; ADOS-G, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic; AHC, amygdala-hippocampus complex; at, anterior; CH, cerebellar hemisphere; CG, cingulate gyrus; Cho, choline-containing compounds; CL, cerebellum; Cre, creatine; CS, centrum semiovale; CV, cerebellar vermis; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; FL, frontal lobe; mI, myo-Inositol; inf, inferior; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; IPS, intraparietal sulcus; IQ, intelligence quotient; MEGA, MEscher – GArwood; MPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; MPL, medial parietal lobe; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; MT, medial temporal; NA, not applicable; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; NS, no significant differences; OL, occipital lobe; PRESS, point-resolved selective spectroscopy; PROBE/SV, PROton Brain Exam/Single Voxel; PL, parietal lobe; pt, posterior; SEMS, Scanning Electron Microscopes; sup, superior; STEAM, 1H-stimulated echo acquisition mode; TE, echo time; TD, typically developed; TL, temporal lobe; TH, thalamus; TPJ, temporoparietal junction; TR, repetition time.

Number of participants with autism spectrum disorder.

Number of controls.

Criteria for IQ or mean IQ of participants.

Table 2. Meta-analyses of metabolites levels comparing subjects with autism spectrum disorders to controls.

| Participants | Region | Metabolites | Total number of ASD vs TD subjects | Total number of studies | Total number of VOIs | Standardized mean differences | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | P-value | I2 | Publication bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Frontal | NAA | 764 vs 531 | 8 | 25 | −0.35 | −0.51 | −0.2 | 0.00001a | 42% | 0.226 |

| Cre | 561 vs 362 | 6 | 19 | −0.24 | −0.43 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 44% | 0.536 | ||

| Cho | 599 vs 378 | 7 | 22 | −0.07 | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 17% | 0.851 | ||

| mI | 314 vs 138 | 4 | 8 | −0.44 | −0.76 | −0.12 | 0.008 | 55% | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Amygdala-hippocampus complex | NAA | 245 vs 115 | 6 | 13 | −0.88 | −1.31 | −0.46 | <0.0001a | 61% | 0.385 | |

| Cre | 129 vs 46 | 3 | 4 | −0.46 | −0.81 | −0.12 | 0.009 | 0% | NA | ||

| Cho | 245 vs 115 | 6 | 13 | −0.11 | −0.53 | 0.3 | 0.59 | 65% | 0.128 | ||

| mI | 128 vs 52 | 3 | 7 | 0.53 | −0.32 | 1.37 | 0.22 | 78% | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Parietal | NAA | 316 vs 233 | 4 | 11 | −0.39 | −0.61 | −0.17 | 0.0006a | 31% | 0.092 | |

| Cre | 178 vs 106 | 2 | 6 | −0.33 | −0.69 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 51% | NA | ||

| Cho | 206 vs 131 | 3 | 9 | −0.07 | −0.29 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0% | NA | ||

| mI | Not enough data | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Glx | No data | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Temporal | NAA | 252 vs 186 | 3 | 6 | −0.55 | −0.89 | −0.22 | 0.001a | 62% | NA | |

| Cre | 142 vs 84 | 2 | 4 | −0.09 | −0.44 | 0.26 | 0.62 | 33% | NA | ||

| Cho | 142 vs 84 | 2 | 4 | −0.17 | −0.72 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 72% | NA | ||

| mI | 142 vs 84 | 2 | 4 | −0.27 | −0.7 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 55% | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Cerebellum | NAA | 151 vs 109 | 5 | 9 | −0.35 | −0.6 | −0.09 | 0.008 | 0% | NA | |

| Cre | 79 vs 68 | 2 | 3 | −0.1 | −0.44 | 0.23 | 0.54 | 0% | NA | ||

| Cho | 151 vs 109 | 5 | 9 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.23 | 0.33 | 11% | NA | ||

| mI | 65 vs 66 | 2 | 4 | 0.29 | 0.68 | −0.31 | 1.67 | 80% | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Thalamus | NAA | 170 vs 98 | 3 | 6 | −0.58 | −0.89 | −0.28 | 0.0002a | 25% | NA | |

| Cre | 170 vs 98 | 3 | 6 | −0.38 | −0.75 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 48% | NA | ||

| Cho | 170 vs 98 | 3 | 6 | −0.44 | −0.83 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 54% | NA | ||

| mI | 126 vs 58 | 2 | 4 | −0.23 | −0.62 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 30% | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Adults | Frontal | NAA | 80 vs 101 | 4 | 6 | 0.1 | −0.4 | 0.59 | 0.7 | 62% | NA |

| Cre | 52 vs 59 | 3 | 4 | 0.24 | −0.15 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 5% | NA | ||

| Cho | 80 vs 101 | 4 | 6 | 0.11 | −0.3 | 0.52 | 0.6 | 47% | NA | ||

| mI | Not enough data | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Amygdala-hippocampus complex | NAA | 62 vs 56 | 4 | 4 | 0.19 | −0.18 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0% | NA | |

| Cre | 62 vs 56 | 4 | 4 | 0.6 | −0.03 | 1.23 | 0.06 | 62% | NA | ||

| Cho | 62 vs 56 | 4 | 4 | 0.43 | −0.25 | 1.11 | 0.22 | 68% | NA | ||

| mI | 50 vs 44 | 3 | 3 | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.8 | 0.07 | 0% | NA | ||

| Glx | Not enough data | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Parietal | NAA | 99 vs 102 | 4 | 7 | −0.37 | −0.65 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0% | NA | |

| Cre | 99 vs 102 | 4 | 7 | −0.15 | −0.43 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0% | NA | ||

| Cho | 99 vs 102 | 4 | 7 | −0.17 | −0.45 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0% | NA | ||

| mI | 73 vs 75 | 2 | 5 | −0.47 | −1.06 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 68% | NA | ||

| Glx | 73 vs 75 | 2 | 5 | −0.22 | −0.55 | 0.1 | 0.18 | 0% | NA | ||

| Cerebellum | NAA | 38 vs 38 | 2 | 3 | −0.7 | −1.16 | −0.23 | 0.004 | 0% | NA | |

| Cre | 38 vs 38 | 2 | 3 | −0.02 | −0.52 | 0.49 | 0.95 | 19% | NA | ||

| Cho | 38 vs 38 | 2 | 3 | −0.29 | −0.75 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0% | NA | ||

| mI | No data | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Glx | No data | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; Cho, choline-containing compounds: Cre, creatine; mI: myo-Inositol; NA, not applicable; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; TD, typically developed.

Statistically significant after Bonferroni-correction.

Results

Study selection

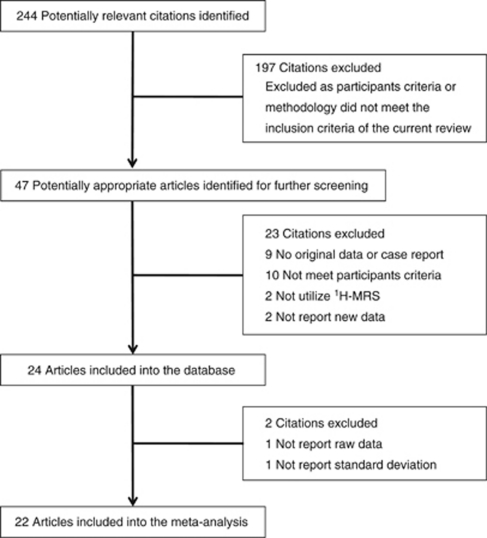

The literature search described above yielded 244 articles, of which 47 studies were identified as potential candidates for the meta-analysis. Nine articles were excluded because lack of the original data. Ten were excluded because they did not recruit ASD individual. Two were excluded because of not utilizing 1H-MRS. Two were excluded because not reporting new data. Thus, 24 studies were included into the database.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 From the database, one study was excluded from the meta-analysis because they did not report raw data regarding the metabolite measure28 and one study was excluded because it did not provide sufficient data to calculate the standardized mean difference36 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Process of study selection.

Database

Studies included in the meta-analysis involved 569 participants with ASD and 415 TD control subjects. Table 1 summarizes variables recorded in the systematic review. Among these studies, 17 examined children,12, 13, 14, 16, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39 including 447 with ASD and 285 with TD, while eight studies examined adults,16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 37, 38 including 122 with ASD and 130 with TD. Fourteen studies recruited participants with mean intelligence quotient 70 or more,12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 25, 26, 37, 38, 39 whereas eight articles did not mention the precise mean or range of intelligence quotient.13, 22, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Three child studies22, 33 included 19 ASD children with comorbid epilepsy, while only one adult study included one ASD subjects with epilepsy.37 Five child studies13, 16, 25, 26, 29 and four adult studies16, 17, 20, 21 included individuals with drug-naïve or no medication only, although medication status was unclear in some studies.22, 28, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39 Diagnosis of ASD was determined based on DSM-IV (15 studies),12, 14, 18, 20, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 36, 37, 38 DSM-III (one study),33 or ICD-10 (five studies)15, 16, 17, 34, 35 criteria. Among the studies employing DSM-IV or DSM-III, 10 used Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 37, 38, 39 or ADI,16 10 utilized Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)14, 16, 21, 37, 38, 39 or Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G),12, 13, 20 and nine employed both.12, 13, 14, 16, 20, 21, 37, 38, 39 For image acquisition, 12 studies utilized point-resolved selective spectroscopy,15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 26, 29, 31, 34, 36, 37 while six employed 1H-stimulated echo acquisition mode sequence.22, 28, 32, 33, 35, 39 Four studies12, 20, 22, 32 used 3-tesla MRI scanners, while 20 studies13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 utilized 1.5-tesla scanners. Twelve child studies12, 13, 14, 16, 22, 28, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 39 and seven adult studies15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 37, 38 employed MRS measures with estimation of absolute measure. Seven child studies12, 13, 14, 16, 25, 32, 39 and five adult studies15, 16, 17, 21, 38 utilized tissue segmentation within VOIs.

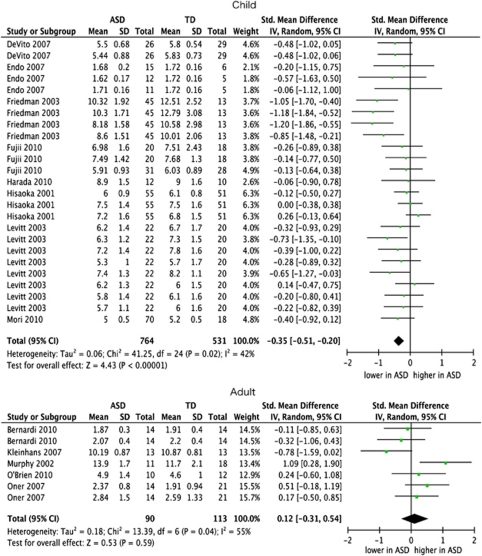

Meta-analysis for metabolite measures in childhood and adulthood

In childhood, individuals with ASD showed significantly reduced NAA levels compared with TD controls in all the brain regions but cerebellum included in the meta-analysis (P<0.05, Bonferroni-corrected; Figure 2). In contrast, no significant difference was found in other metabolite concentrations between children with ASD and TD controls. Although several metabolites showed differences in levels between children with ASD and TD at the trend level significance (NAA in the cerebellum: P=0.008; mI in the frontal areas: P=0.008; Cre in the frontal areas: P=0.01, in AHC: P=0.009; in the thalamus: P=0.04; Cho in the thalamus: P=0.03), these significant effects disappeared after the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of frontal N-acetylaspartate (NAA). Standardized mean differences for NAA measures in frontal lobe between subjects with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and those with typical development (TD) in child and adulthood. The forest plot displays standardized mean differences and 95% confidential intervals (CIs).

In contrast to childhood, no metabolites showed a significant difference in metabolites levels between people with ASD and TD in adulthood. The NAA levels in the parietal lobe and cerebellum showed a trend for decreased measures in adults with ASD compared with those with TD (P=0.01 in the parietal lobe and P=0.004 in the cerebellum), although these differences did not reach statistical significance after the Bonferroni correction was applied (Table 2).

In addition, it was confirmed that Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons were not too strict, because correction using the Student–Newman–Kuels procedure did not change the results both for childhood and adulthood.

Sensitivity analyses

All sensitivity analyses performed in the specified-subgroups with more homogeneous quality showed significant reductions in NAA measures in the frontal lobe of children with autism (P<0.05, Bonferroni-corrected). These results demonstrated the robustness of reduced frontal NAA level during childhood even after considering methodological and participant's heterogeneity such as comorbidity of other neuropsychiatric diseases and intellectual disability, medication status, diagnostic methods, field strength of MR scanner, types of MRS measures and implementation of segmentation within VOI. In the other areas, some sensitivity analyses revealed that the significant effect of low NAA level disappeared in some subgroups. In the AHC, parietal cortex, temporal regions and thalamus, the significance of NAA reductions was preserved in the most subgroups, such as ASD individuals with no comorbid epilepsy, no medications and acquisition of MRS in a 1.5-tesla scanner (Supplementary Table 1).

Meta-regression

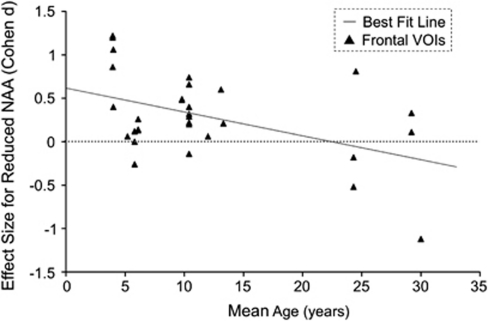

The current meta-regression revealed a significant inverse effect of mean age of participants on NAA measures in the frontal lobe (P=0.009), but in the AHC or parietal cortex (Figure 3). Even after excluding heterogeneity of participants and methodologies in the included study, meta-regression analyses in specified subgroups further demonstrated the significant effects of mean age in the frontal lobe. These analyses were performed in studies with implementation of segmentation within VOIs (P<0.001), with multi-voxel MRS (P=0.021), with 1.5-tesla scanner (P=0.004), with participants without comorbid epilepsy (P=0.001), without medication (P=0.006), without mental retardation (P=0.032) and without participants diagnosed not using ADI-R or ADOS (P=0.006).

Figure 3.

The relationship between effect sizes for reduced N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and ages of study participants. Effect sizes from each comparison of VOIs are plotted by the mean age of participants with autism spectrum disorders of the study. The line of best fit shows a gradual but substantial decrease in NAA reduction. No data were obtained from individuals before the age of 4 years.

The meta-regression revealed significant effects of the type of MRS measures and the employment of segmentation within VOIs on the NAA levels in AHC (P<0.05). However, no potential modifiers significantly affect the NAA levels in the frontal and parietal regions (Supplementary Table 2).

Between-study heterogeneity

No significant heterogeneity was detected in all the metabolites in any regions but in mI measure in AHC and cerebellum during childhood (I2=78% and 80%, respectively) (Table 2).

Publication bias

The linear regression test showed significant publication bias was not detected in most metabolites (5/6) but in the parietal NAA of children (P<0.1; Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of 1H-MRS studies in people with ASD. A total of 22 studies were integrated in the meta-analyses, of which 1476 1H-MRS measures from 31 data sets at maximum, 844 measures from ASD and 632 measures from TD individuals.

The current meta-analysis demonstrated that NAA levels in the frontal, parietal, temporal lobule, AHC and thalamus were significantly lower in ASD children compared with TD controls. In contrast, no significant difference in the any metabolite levels was found in adulthood. Importantly, our meta-regression analysis provides the first evidence that the degree of lower frontal NAA levels linearly declined with aging from childhood to adulthood in ASD people. The systematic review showed obvious methodological heterogeneities across studies, including in comorbid epilepsy, psychotropic medications, mental retardation, field strength of MR scanners, types of MRS measures, utilization of segmentation within VOIs and diagnostic tools. However, the sensitivity analyses further emphasized the robustness of current findings, especially regarding the lower-than-normal frontal NAA level in ASD children, since the potential confounds, heterogeneity between studies and publication bias did not significantly affect the findings.

The finding of robustly lower-than-normal frontal NAA during childhood seems to be consistent with the importance of this area in the pathophysiology of ASD indicated by previous findings from several lines of research.6, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Previous functional imaging studies have repeatedly reported dysfunctional prefrontal cortices during psychological tasks requiring theory of mind,47 social perception48, 49 and self-referencing.43 The presence of early brain enlargement especially in frontal lobe50 shown on structural MRI in autism is well established.3, 4, 5 Previous post-mortem studies have also shown several deviations in various histological tissues including glial cells, von Economo neurons and neuronal organization in frontal cortices of ASD.6

The present linear regression analysis demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between decrement of frontal NAA and mean age in ASD subjects. Previous brain structural findings revealed abnormal trajectory of brain growth, such that the overall brain size in autism was slightly reduced at birth, dramatically increased within the first year of life, then gradually plateaued in adulthood.3, 4, 5 As the current meta-analyses included studies involving participants with mean ages between 4 and 35, the period of which the meta-analyses covered corresponds to the phase of gradual dissipation of early brain overgrowth in ASD. It is notable that the decrease and subsequent recovery in NAA level was found during the period showing a significant increase and subsequent normalization in brain size in ASD, because these overlapping effects were inferred on the basis of independent data.

The current neurochemical findings could provide some insight into the histochemical background of the abnormal trajectory of autistic brain growth. Although the histological background is yet to be uncovered, several hypotheses have been formulated.6, 7 These hypotheses could be divided into two major categories. The first is abnormalities associated with neurons: for example, excessive numbers of neuron, synapse, or minicolumns and excessive and/or premature growth of axon, dendrite, or neuron cell bodies. The second is abnormalities associated with glial cells, such as excessive numbers of glia, activated and enlarged glia, and excessive and/or premature myelination. NAA is localized mainly in the cell bodies, axons, dendrites and dendritic spines of mature neurons, and is considered to function as a marker of functional and structural neuronal integrity.9 Although recent studies have suggested NAA expressed by oligodendrocytes,51 NAA is less distributed in glia.52 Therefore, since brain enlargement because of increase in neuron number should heighten NAA level in autistic brain, it is more likely that reduced NAA measures during childhood reflect decreased neuron density induced by increasing brain volume because of a factor other than associated with neurons.

Considered together, among the two possible explanations for early brain expansion in ASD, increased cell bodies, axons, dendrites and dendritic spines of neurons seems less likely than abnormalities associated with glia. Glial cells (for example, astrocytes) have been shown to increase in volume after birth.53 As glial cells initially occupy large percentage of brain volume,54 increased glial cell volume may be a major factor in brain enlargement without a significant increase in the NAA measure of 1H-MRS. Previous post-mortem studies have reported glial abnormalities that can contribute the abnormal volume increase, such as microglial and astroglial activation and increased microglial density, in the prefrontal cortex in ASD.55, 56 Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that proliferation of glial cells diluting the density of neurons is a major factor in the abnormal brain overgrowth and decreased NAA levels observed in children with ASD.

The hypothesis that proliferation of glia could cause brain expansion with decreased neuron density and low NAA is consistent with observations in some neurological and genetic diseases. Previous studies have demonstrated decreased NAA because of abnormal synthesis of glia in patients with glioma.57 Some other diseases manifesting macrocephaly, for example, neurofibrosis type 1 demonstrates decreased NAA measures. It was concluded that the reduced NAA measures in neurofibrosis type 1 was caused by increased brain volume because of excess myelination.58

Proliferation of glia can also explain the transient brain expansion during the neonatal period and infancy, and is consistent with the subsequent preservation of behavioral dysfunction in the period of gradually normalizing for brain expansion in ASD. Transient microglial cell proliferation and subsequent irreversible dysfunction could occur after inflammation or hypoperfusion.59 Existence of inflammation or hypoperfusion during neonatal and infancy in ASD has also been suggested by several lines of evidence,55, 56 including decreased serum levels of adhesion molecules and a correlation with head circumference at birth.60 Diminishing of transiently increased glia after early infancy is consistent with the normalization of transiently expanded brain size and decreased NAA during the overlapped time period. However, because we could not find the MRS study involved the participants with the age <1, abnormal brain growth during this period is out of the finding of the current meta-analysis.

Several methodological considerations and limitations of our study should be considered. First, because of the nature of meta-analysis, we can make statistical analysis only at the level of studies. There is no way to confirm whether the participants of included studies actually exhibited enlarged brains during childhood. Second, although inverse effect of age on frontal NAA was shown robustly by the meta-regression analysis performed with the child–adult combined group, it remains unclear whether NAA levels in adults with ASD are equal to, or exceed, levels in TD, because of the relatively small number of included studies in adulthood. Third, because the most included studies utilized 1.5-tesla instead of 3-tesla scanner, it might be insufficient to collect reliable data about several metabolites, which could not be reliably evaluated with insufficient strength of magnetic field such as Glx. Fourth, the included studies display considerable heterogeneity such as variations in the type of metabolite measures and implementation of segmentation. The use of a ratio to Cre is based on the hypothesis that there is no difference in Cre levels between ASD and TD, which is shown to be questionable in the current meta-analysis. Not implementing segmentation is also based on the hypothesis the same proportion of cerebrospinal fluids in each VOI between cases and controls, while structural differences between ASD and TD have been repeatedly demonstrated. Furthermore, the abnormalities in metabolites level of ASD were reported to be different between those in gray matter and white matter.30 We employed the random effect model and the sensitivity analyses in more homogeneous subgroups to control the heterogeneity, and the main findings were preserved when the heterogeneity was controlled. However, the current results were partially affected by such heterogeneity, and should be interpreted carefully. Fifth, although we categorized locations of VOIs into six brain areas with the similar developmental origin,24 the classification might be criticized to be over-simplified considering the functional variability within each sub-areas.

In conclusion, the current meta-analysis robustly showed a significant frontal NAA reduction in ASD children compared with TD, and further demonstrated a significant linear correlation between older age and a smaller magnitude of NAA decrease. This NAA reduction then disappeared in adulthood. Taken together with previous findings suggesting early brain overgrowth and subsequent normalization during the same time period, the current findings support the hypothesis that abnormal brain enlargement in ASD is mainly caused by increases of non-neuron tissues, such as glial cell proliferation. The current systematic review and meta-analysis emphasized the importance and implication for future research. Future longitudinal and large-scale original study with sufficient statistical power that is free from the methodological limitations is required to test the current hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this study were supported by CREST (Japan Science and Technology Agency) and KAKENHI (MEXT) (22689034 to HY). We thank all the authors of the included studies.

Author contributions. YA and HY performed study screenings independently. In the case of discrepancies, a consensus was reached by means of discussion with the third reviewer (KK). YA performed all the data extraction and computation of effect size twice to avoid carelessness mistake. HY further performed data extraction and computation of the effect sizes independently. YA and HY wrote paper.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Frith U, Happe F, Siddons F. Autism and theory of mind in everyday life. Soc Dev. 1994;3:108–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02720324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U, Happe F. Language and communication in autistic disorders. Phil Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 1994;346:97–104. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redcay E, Courchesne E. When is the brain enlarged in autism? A meta-analysis of all brain size reports. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N. Evidence of brain overgrowth in the first year of life in autism. JAMA. 2003;290:337–344. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett HC, Poe MD, Gerig G, Styner M, Chappell C, Smith RG, et al. Early brain overgrowth in autism associated with an increase in cortical surface area before age 2 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:467–476. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Bridging the gap between MRI and postmortem research in autism. Brain Res. 2011;1380:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, Pierce K, Schumann CM, Redcay E, Buckwalter JA, Kennedy DP, et al. Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron. 2007;56:399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Inubushi T. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in affective disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:133–147. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CE, Lowry M, Horsman A. Unchanged basal ganglia N-acetylaspartate and glutamate in idiopathic Parkinson's disease measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Mov Disord. 1997;12:297–301. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross B. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the human brain. Anat Rec. 2001;265:54–84. doi: 10.1002/ar.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Breeze J, Kukes T, Rose S. Effects of myo-inositol ingestion on human brain myo-inositol levels: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1197–1202. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devito T, Drost D, Neufeld R, Rajakumar N, Pavlosky W, Williamson P, et al. Evidence for cortical dysfunction in autism: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Shaw D, Artru A, Richards T. Regional brain chemical alterations in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Neurology. 2003;60:100–107. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt J, O'NEILL J, Blanton R, Smalley S, Fedale D, McCracken JT, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of the brain in childhood autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1355–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D, Critchley H, Schmitz N, McAlonan G, Amelsvoort TV, Robertson D, et al. Asperger syndrome: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:885–891. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien FM, Page L, O'Gorman RL, Bolton P, Sharma A, Baird G, et al. Maturation of limbic regions in Asperger syndrome: a preliminary study using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Res. 2010;184:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page L, Daly E, Schmitz N, Simmons A, Toal F, Deeley Q, et al. In vivo 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of amygdala-hippocampal and parietal regions in autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2189–2192. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner O, Devrimci-Ozguven H, Oktem F, Yagmurlu B, Baskak B, Munir KM. Proton MR spectroscopy: higher right anterior cingulate N-acetylaspartate/choline ratio in Asperger syndrome compared with healthy controls. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1494–1498. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan NM, Shaw DWW, Richards TL, Estes AM, Friedman SD, Petropoulos H, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MRI reveal no evidence for brain mitochondrial dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:105–115. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1216-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi S, Anagnostou E, Shen J, Kolevzon A, Buxbaum JD, Hollander E, et al. In vivo 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the attentional networks in autism. Brain Res. 2011;1380:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Nishimura K, Sugihara G, Nakamura K, Tsuchiya KJ, Matsumoto K, et al. Metabolites alteration in the hippocampus of high-functioning adult subjects with autism. Int J Neuropsychopharm. 2010;13:529–534. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K. Iryoteki-taio. No To Hattatsu. 2010;42:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Shioiri T, Kitamura H, Kimura T, Endo S, Masuzawa N, et al. Altered chemical metabolites in the amygdala-hippocampus region contribute to autistic symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabis L, Huang W, Azizian A, DeVincent C, Tudorica A, Kesner-Baruch Y, et al. 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy markers of cognitive and language ability in clinical subtypes of autism spectrum disorders. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:766–774. doi: 10.1177/0883073808315423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Wiley: Chichester, UK; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chugani DC, Sundram BS, Behen M, Lee ML, Moore GJ. Evidence of altered energy metabolism in autistic children. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiat. 1999;23:635–641. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(99)00022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayed N, Modrego P. Comparative study of cerebral white matter in autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder by means of magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:566–569. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Shaw D, Artru A, Dawson G, Petropoulos H, Dager S. Gray and white matter brain chemistry in young children with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:786–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii E, Mori K, Miyazaki M, Hashimoto T, Harada M, Kagami S. Function of the frontal lobe in autistic individuals: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic study. J Med Invest. 2010;57:35–44. doi: 10.2152/jmi.57.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Taki MT, Nose A, Kubo H, Mori K, Nishitani H, et al. Non-Invasive evaluation of the GABAergic/glutamatergic system in autistic patients observed by MEGA-editing proton MR spectroscopy using a clinical 3 tesla instrument. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;41:447–454. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Tayama M, Miyazaki M, Yoneda Y, Yoshimoto T, Harada M, et al. Differences in brain metabolites between patients with autism and mental retardation as detected by in vivo localized proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:91–96. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisaoka S, Harada M, Nishitani H, Mori K. Regional magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain in autistic individuals. Neuroradiology. 2001;43:496–498. doi: 10.1007/s002340000520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka H, Harada M, Mori K, Hisaoka S, Nishitani H. Brain metabolites in the hippocampus-amygdala region and cerebellum in autism: an 1 H-MR spectroscopy study. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:517–519. doi: 10.1007/s002340050795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos MM, Brito AR, Domingues RC, Cruz LCH, Jr, Werner J, Jr, Gonçalves JP. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in school-aged autistic children. J Neuroimaging. 2008;18:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans N, Schweinsburg B, Cohen D, Müller R, Courchesne E. N-acetyl aspartate in autism spectrum disorders: regional effects and relationship to fMRI activation. Brain Res. 2007;1162:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Weaver KE, Liang O, Dawson G, Aylaward E. Biochemical correlates of clinical impairment in high functioning autism Asperger's disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:1079–1086. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0707-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan A, Minshew NJ, Melhem NM, Srihari S, Jo B, Bansal R, et al. An MRI and proton spectroscopy study of the thalamus in children with autism. Psychiatry Res. 2008;163:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD. Interacting minds—a biological basis. Science. 1999;286:1692–1695. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U. Mind blindness and the brain in autism. Neuron. 2001;32:969–979. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Mottron L, Peng D, Berthiaume C, Dawson M. Local bias and local-to-global interference without global deficit: a robust finding in autism under various conditions of attention, exposure time, and visual angle. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2007;24:550–574. doi: 10.1080/13546800701417096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Bullmore ET, Sadek SA, Pasco G, Wheelwright SJ, et al. Atypical neural self-representation in autism. Brain. 2010;133:611–624. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl CW, Dierker D, Mostafavi I, Schumann CM, Rivera SM, Amaral DG, et al. Cortical folding abnormalities in autism revealed by surface-based morphometry. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11725–11735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0777-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S, Yamasue H, Abe O, Suga M, Yamada H, Inoue H, et al. Reduced gray matter volume of pars opercularis is associated with impaired social communication in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasue H, Kuwabara H, Kawakubo Y, Kasai K. Oxytocin, sexually dimorphic features of the social brain, and autism. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:129–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli F, Frith C, Happé F, Frith U. Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain. 2002;125:1839–1849. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey KA, Morris JP, McCarthy G. Neural basis of eye gaze processing deficits in autism. Brain. 2005;128:1038–1048. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser MD, Hudac CM, Shultz S, Lee SM, Cheung C, Berken AM, et al. Neural signatures of autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21223–21228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010412107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carper R. Cerebral lobes in autism: early hyperplasia and abnormal age effects. Neuroimage. 2002;16:1038–1051. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjartmar C, Battistuta J, Terada N, Dupree E, Trapp BD. N-acetylaspartate is an axon-specific marker of mature white matter in vivo: a biochemical and immunohistochemical study on the rat optic nerve. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:51–58. doi: 10.1002/ana.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urenjak J, Williams S, Gadian D. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy unambiguously identifies different neural cell types. J Neurosci. 1993;13:981–989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00981.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR. Glial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1861–1867. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2004;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JT, Chana G, Pardo CA, Achim C, Semendeferi K, Buckwalter J, et al. Microglial activation and increased microglial density observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebell E, Fiehler J, Ding X. Disarrangement of fiber tracts and decline of neuronal density correlate in glioma patients—a combined diffusion tensor imaging and 1H-MR spectroscopy study. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1426–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PY, Kaufmann WE, Koth CW, Denckla MB, Barker PB. Thalamic involvement in neurofibromatosis type 1: evaluation with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberg G. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:312–318. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya K, Hashimoto K, Iwata Y, Tsujii M, Sekine Y, Sugihira G, et al. Decreased serum levels of platelet-endothelial adhesion molecule (PECAM-1) in subjects with high-functioning autism: a negative correlation with head circumference at birth. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1056–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Hashimoto T, Harada M, Yoneda Y, Shimakawa S, Fujii E, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the autistic brain. No To Hattatsu. 2001;33:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.