Abstract

To gain insight into mechanisms controlling SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2 (Sox2) protein activity in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs), the endogenous Sox2 gene was tagged with FLAG/Hemagglutinin (HA) sequences by homologous recombination. Sox2 protein complexes were purified from Sox2/FLAG/HA knockin ESCs, and interacting proteins were defined by mass spectrometry. One protein in the complex was poly ADP-ribose polymerase I (Parp1). The results presented below demonstrate that Parp1 regulates Sox2 protein activity. In response to fibroblast growth factor (FGF)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling, Parp1 auto-poly ADP-ribosylation enhances Sox2-Parp1 interactions, and this complex inhibits Sox2 binding to octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct4)/Sox2 enhancers. Based on these results, we propose a unique mechanism in which FGF signaling fine-tunes Sox2 activity through posttranslational modification of a critical interacting protein, Parp1, and balances the maintenance of ESC pluripotency and differentiation. In addition, we demonstrate that regulation of Sox2 activity by Parp1 is critical for efficient generation of induced pluripotent stem cells.

Keywords: regulatory pathway, gene targeting, tagged mice

Mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which are derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of blastocyst-stage embryos, are pluripotent and, therefore, can efficiently form tissues derived from all three germ layers. Cells in the ICM are pluripotent during a narrow window of development; however, pluripotency can be maintained almost indefinitely in culture under the appropriate conditions. Extrinsic factors such as leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (1) and bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) (2) are required for propagating ESCs in an undifferentiated state. In addition, suppression of prodifferentiation signals through the FGF pathway also enhances pluripotency (3, 4). Intrinsic factors, such as the transcription factors Oct4 (5), SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2 (Sox2) (6), and Nanog (7), are also critical determinants of pluripotency. Sox2 cooperates with Oct4 to activate downstream target genes by binding to Oct-Sox enhancers. To date, ESC-specific Oct-Sox enhancers have been found in several genes, including Fgf4 (8), Nanog (9, 10), undifferentiated embryonic cell transcription factor 1 (UTF1) (8), Oct4, and Sox2 (6, 11). In addition, an ESC-specific enhanceosome complex including Oct4/Sox2/Nanog binds to a number of downstream genes involved in ESC pluripotency (12–14). Common targets of the Oct4/Sox2/Nanog trio include actively transcribed genes and inactive genes; therefore, these core regulators maintain pluripotency via both active and repressive mechanisms (15).

Regulation of the core factors themselves is another important determinant of pluripotency. The ground state of pluripotency is extremely sensitive to the dosage of Oct4 and Sox2. Relatively small fluctuations in the concentration of Oct4 can dramatically affect pluripotency (16, 17). Similarly, relatively small decreases in Sox2 levels trigger ESC differentiation into trophectoderm-like cells, inhibit Oct-Sox targets and induce expression of various lineage markers (18–20). Oct4 and Sox2 expression is stabilized by transcriptional regulation through a series of auto-regulatory feedback loops (21–23); however, little is known about the mechanisms that precisely regulate core factor protein levels.

To gain insight into mechanisms controlling Sox2 activity in ESCs, we replaced the endogenous Sox2 gene with a FLAG/HA-tagged Sox2 by homologous recombination. Sox2 protein complexes were purified by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody, and interacting proteins were defined by high-resolution mass spectrometry. One of the proteins clearly identified in the complexes was poly ADP-ribose polymerase I (Parp1). The results presented below demonstrate that Parp1 regulates Sox2 protein activity. In response to FGF/ERK signaling, Parp1 auto-poly ADP-ribosylation (PARylation) enhances Sox2-Parp1 interactions that inhibit Sox2 binding to Oct-Sox enhancers. Based on these results, we propose a unique mechanism in which FGF signaling fine-tunes the level of Sox2 activity through posttranslational modification of a critical interacting protein, Parp1, and balances the maintenance of ESC pluripotency and differentiation. In addition, we demonstrate that regulation of Sox2 by Parp1 is critical for efficient generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Gao et al. (24) have previously described the interaction of Parp1 and Sox2 in ESCs. The authors reported that Parp1 PARylates Sox2 and relieves Sox2 repression of FGF4 gene expression. In contrast, we report that Parp1 does not PARylate Sox2 but instead PARylates itself. Moreover, we demonstrate that Parp1-Sox2 interactions are regulated by Parp1 auto-PARylation in response to FGF/ERK signaling. These results suggest a unique mechanism for maintenance of pluripotency; that is, Parp1 mediates a protein feedback loop that regulates the pluripotency factor Sox2.

Results

Sox2 Interacts with Parp1 in Mouse ESCs.

Sox2 overexpression in ESCs results in differentiation (19). To study Sox2 in ESCs under conditions that maintain pluripotency, we first used gene-targeted homologous recombination in ESCs to fuse a 3XFLAG/HA tag to the Sox2 carboxy terminus (Fig. S1 A and B). Heterozygous-tagged Sox2 knockin ESCs were used to produce chimeric mice and, subsequently, adult homozygous knockin animals were obtained. No gross phenotypic abnormalities were observed in these mice; therefore, physiologically relevant Sox2 complexes are apparently formed and are fully functional. Sox2-containing complexes were isolated from heterozygous Sox2 knockin ESCs by affinity purification. Immunoprecipitated proteins from Sox2/FLAG/HA and wild-type ESCs were separated by SDS-PAGE. Individual bands that were present in Sox2/FLAG/HA immunoprecipitations (IPs) and not in wild-type IPs were excised and subjected to high-resolution liquid chromatography (LC)-linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) Fourier transform (FT) tandem mass spectrometry analysis (MS/MS) (Fig. S1C). Parp1 was clearly identified in the endogenous FLAG/HA Sox2 IPs and not in wild-type IPs (Fig. S1C).

Parp1 is a nuclear enzyme that belongs to the 18-member Parp family and catalyses PARylation, a transient, reversible posttranslational modification (25). Parp1 cleaves ADP-ribose moieties from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and uses these molecules to construct 2- to 200-unit linear and branched chains of poly(ADP-ribose), or PAR. Parp1 also attaches these PARs to target proteins (PARylation) and to itself (auto-PARylation) (26). Poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (Parg) rapidly degrades protein-bound PARs to free ADP-ribose monomers, and maintains most Parp1 in an unPARylated, inactive status, poised for an immediate response to stimuli (27). Parp1 was initially demonstrated to play a role in DNA repair (28–30). However, recent studies have shown that Parp1 is a multifunctional protein involved in transcriptional regulation (26), epigenetics (31), and apoptosis (32).

To verify the Parp1-Sox2 interaction suggested by the mass spectrometry data, we performed coimmunoprecipitations using knockin Sox2 ESC nuclear extracts. Immunoprecipitation with FLAG antibody to Sox2/FLAG/HA pulled down Parp1 [see Parp1 immunoblotting (IB) in Fig. S1D, Upper Left]. Also, Parp1 immunoprecipitation pulled down Sox2/FLAG/HA (see anti-FLAG IB in Fig. S1D, Upper Right). Finally, immunoprecipitation with Sox2 antibody pulled down Parp1 (see Parp1 IB in Fig. S1D, Lower).

Among other Parp members, Parp2 is the major contributor of residual Parp enzymatic activity in Parp1-disrupted cells (33, 34), and Parp1/Parp2 double knockout animals die during early embryonic development (35, 36). As Parp1 was reported to form heterodimers with Parp2 in HeLa cells (37), we questioned whether Parp2 interacts with Parp1 in ESCs. Using cell lysates derived from wild-type ESCs, we demonstrate that immunoprecipitation with Parp2 antibody pulls down Parp1 (see Parp1 IB in Fig. S1D, Lower).

To facilitate further experiments, we produced ESCs with an HA/3XFLAG tag fused to the amino terminus of Parp1, and show that tagged Parp1 interacts with Sox2 (Fig. S2, Table S1).

Parp1 and Parp2 Repress Oct-Sox Targets.

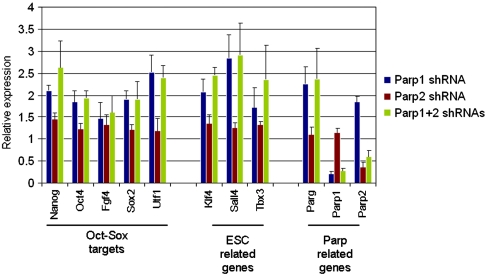

To further test the functional relevance of Parp1 and Parp2 interaction with Sox2, we examined loss-of-function phenotypes by introducing shRNAs against Parp1 and Parp2 into ESCs. Gene expression profiles were assayed by nCounter (Nanostring Technologies) at 4 d post transduction. Notably, Parp2 was upregulated in Parp1-depleted cells and Parp1 was upregulated in Parp2-depleted cells, suggesting a reciprocal compensation between Parp1 and Parp2 in ESCs. Expression of Nanog (9, 10), Fgf4 (8), Utf1 (8), Oct4, and Sox2 (6, 11) (genes thought to be regulated by Oct-Sox enhancers) was substantially increased in Parp1-knockdown, Parp2-knockdown, and double-knockdown assays (Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that Parp1 and Parp2 play important roles in the control of genes regulated by Oct-Sox enhancers (Nanog, Oct4, Fgf4, Sox2, and Utf1). Also, several pluripotent marker genes [Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4), T-box 3 (Tbx3), and Sal-like protein 4 (Sall4)] that do not contain functionally characterized Oct-Sox enhancers are nevertheless upregulated by Parp1/Parp2 knockdown (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Parp1 and Parp2 repress Oct-Sox targets. Gene expression was determined by quantifying RNA transcripts using nCounter analysis (Nanostring Technologies). Wild-type ESCs were transduced with lentiviral shRNA vectors to Parp1, Parp2 and control sequences. Cells were collected 4 d post transduction for RNA analysis. Expression levels are shown relative to the control shRNA (relative expression = 1), and error bars represent standard deviation of the mean (n = 4). All mean values for experimental verses control samples were significant at p < 0.05 except for Utf1 with Parp2 knockdown (p < 0.5) and Parg with Parp2 knockdown (p < 0.5).

Surprisingly, stable knockdowns of Parp1 and Parp2 resulted in slightly different gene expression patterns. As observed in transient knockdowns, expression of Nanog and Klf4 was upregulated in individual clones isolated from all three knockdown groups (Fig. S3). However, expression of Oct4 and Sox2 was not significantly increased and expression of Fgf4 and Utf1 was slightly decreased (Fig. S3). These data are consistent with the Parp1 knockout results published by Gao et al. (24); Sox2 expression did not change in the absence of Parp1 and expression of Fgf4 was decreased by 40% in Parp1 knockout ESCs. Ogino et al. (38) have also reported that changes in expression of pluripotency genes are minimal in Parp1 knockout cells. We speculate that the differences in gene expression data observed between Parp1 knockouts (or Parp1 stable knockdowns) and our transient Parp1 knockdowns are due to clonal selection; that is, in Parp1 knockout or stable knockdowns, only undifferentiated ESC clones in which transcriptional feedback loops gradually adjust Oct4 and Sox2 to normal levels are selected.

PARylation of Parp1 Regulates Sox2 Activity.

Parp1 is both a positive and negative regulator of transcription. Parp1 positively regulates transcription by displacing histone H1 at many RNA polymerase II (pol II) promoters (39). In the absence of NAD+, Parp1 represses transcription by condensing chromatin (40, 41). To investigate Parp1 binding to Oct-Sox targets, we employed ChIP to map the DNA binding pattern of Parp1 at the Sox2 and Nanog loci. Parp1 binding in HA tagged Parp1 ESCs was enriched at the Sox2 gene promoter and at the Nanog promoter (Fig. S4). Interestingly, the Sox2 and Nanog promoters were also bound by Sox2 in HA-tagged Sox2 ESCs (Fig. S4). These results suggest that Parp1-Sox2 complexes bind to Sox2 and Nanog regulatory elements.

Given the well-characterized enzymatic activity of Parp1, we next investigated whether Sox2 is PARylated by Parp1 in ESCs. When recombinant Parp1 was incubated with radiolabeled NAD+ in a biochemical assay, an auto-PARylation signal was detected at the predicted molecular weight of Parp1 (Fig. S5A). This PARylation result was further validated by Parp inhibitor treatment. Although PARylation of Parp1 was high, when Sox2 was added to the reaction, no signal at the predicted position of Sox2 was detected. This result indicates that Sox2 was not PARylated in this assay (Fig. S5A). Next, permeabilized-tagged Sox2 knockin (KI) ESCs and tagged Parp1 KI ESCs were incubated with radiolabeled NAD+ and subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with control and FLAG antibodies. Only FLAG immunoprecipitates from Parp1 knockin ESCs displayed a signal after autoradiography (Fig. S5B). Together, these data demonstrate Parp1 PARylation in ESCs; however, we do not observe Sox2 PARylation in ESCs as reported previously (24).

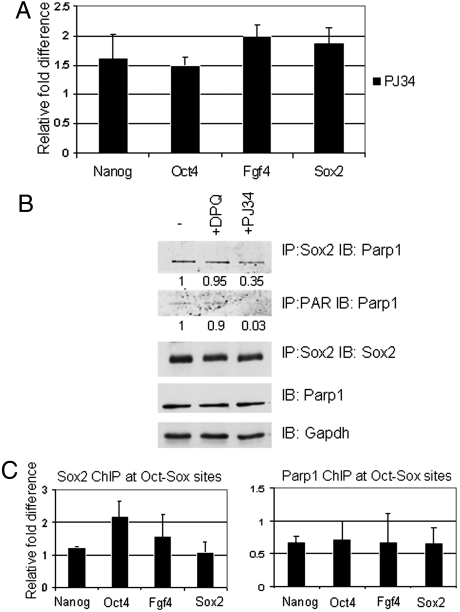

Parp1 is the primary PAR recipient (42, 43). To further investigate the importance of PARylation in ESCs, we assayed the expression profile of Oct-Sox targets in the presence of the Parp inhibitor, PJ34. Expression of Oct-Sox targets (Nanog, Oct4, Fgf4, and Sox2) was upregulated in the presence of Parp inhibitor (Fig. 2A). These data are consistent with the results of Parp1, Parp2, and Parp1/Parp2 knockdowns presented above (Fig. 1). The data suggest that PARylation regulates Sox2 activity at Oct-Sox target genes; however, Sox2 itself is not PARylated.

Fig. 2.

PARylation of Parp1 regulates Sox2 activity. (A) Expression of Oct-Sox targets are up-regulated by Parp inhibitors. Nanog, Oct4, Fgf4, and Sox2 RNA levels were determined by RT-quantitative PCR after cells were treated with the PARylation inhibitor, PJ34. Expression levels are shown relative to controls (no inhibitor; relative expression = 1), error bars represent standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). All mean values for experimental (PJ34 treated) verses control (no inhibitor) samples were significant at p < 0.05. (B) Inhibition of PARylation decreases Sox2-Parp1 interaction. Wild-type ESCs were treated with or without Parp inhibitors PJ34 or DPQ, and Sox2-Parp1 complexes were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. The bottom two rows are nonimmunoprecipitated controls. All bands were quantitated by densitometry (ChemiDoc imaging system, BioRad). Values for Sox2-Parp1 (IP: Sox2 IB: Parp1) and PARylated Parp1 (IP: Parp1 IB: PAR) were normalized to values of total Parp1 (IB: Parp1) and GAPDH (IB: GAPDH). Total Parp1 and GAPDH were determined by immunoblotting of the same ESC whole cell extracts used for the IPs (1% of volume used for IP). Without inhibitor (-), a value of 1 was assigned to (IP: Sox2 IB: Parp1)/(IB: Parp1)/(IB: GAPDH) and to (IP: PAR IB: Parp1)/(IB: Parp1)/(IB: GAPDH). With inhibitors, similar calculations resulted in the values indicated. (C) Inhibition of PARylation enhances Sox2 binding to Oct-Sox binding sites in ESCs. Chromatin samples derived from Sox2 knockin and Parp1 knockin ESCs treated with or without Parp inhibitor (PJ34) were immunoprecipitated with HA antibody. Purified ChIP DNA fragments were assayed by qPCR. Bars represent relative enrichment of Sox2 or Parp1 binding to Nanog, Oct4, Fgf4, and Sox2 regulatory elements. Values are shown relative to the no inhibitor treatment controls (no inhibitor; relative level = 1). Error bar represents standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). Mean values for experimental (PJ34 treated) verses control (no inhibitor) samples were significant at the following p values: Sox2 ChIP at promoters of Nanog, p = 0.02; Oct4, p = 0.02; Fgf4, p = 0.14; and Sox2, p = 0.06. Parp1 CHIP at promoters of Nanog, p = 0.05; Oct4, p = 0.1; Fgf4, p = 0.19; and Sox2 p = 0.06.

To provide insights into the mechanism by which Parp1 auto-PARylation influences Sox2 binding to Oct-Sox target genes, we determined whether Parp1 PARylation changes Parp1-Sox2 interactions. Previous data demonstrated that linkage of a long negatively charged PAR polymer to a protein can alter subsequent protein-protein interactions in both positive (44, 45) and negative ways (46). In Fig. 2B, we demonstrate that Parp1-Sox2 interaction is decreased when PARylation is inhibited with 3,4-Dihydro-5[4-(1-piperindinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)-isoquinoline (DPQ) or with the more potent inhibitor PJ34 in ESCs. We next determined whether inhibition of PARylation affects Sox2 binding to the Oct-Sox enhancer in ESCs. The ChIP-quantitative PCR data in Fig. 2C demonstrate that Sox2 binding to the Oct-Sox enhancer of the Oct4 gene was increased twofold in inhibitor-treated ESCs and that Sox2 binding to the Oct-Sox enhancer of the Fgf4 gene was also increased. Importantly, inhibition of PARylation decreases Parp1 binding at Oct-Sox targets (Fig. 2C, Right). These results (Fig. 2 A–C, Fig. S5 A and B) demonstrate that inhibition of PARylation (i) inhibits Parp1-Sox2 interaction, (ii) increases expression of Oct-Sox target genes, (iii) decreases Parp1 binding to Oct-Sox sites, and (iv) enhances Sox2 binding to Oct-Sox elements, most significantly, in the Oct4 promoter. All of the data described above suggest a model in which Parp1 auto-PARylation controls Sox2 binding to Oct-Sox sites and prevents overexpression of Oct-Sox target genes. Therefore, Sox2-PARylated Parp1 complexes fine-tune the level of Oct-Sox target gene expression to maintain pluripotency.

Sox2-Parp1 Interaction is Required for Differentiation.

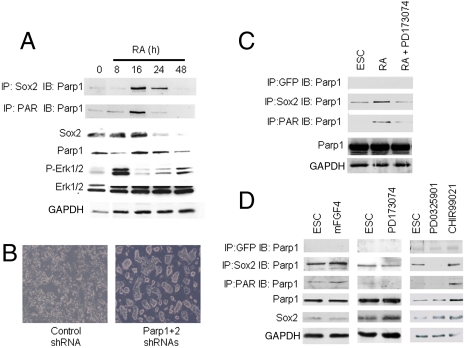

Downregulation of pluripotent factors is critical for the initiation of ESC differentiation. The mechanisms involved in disrupting the Oct4-Sox2-Nanog transcriptional circuitry to initiate differentiation are poorly understood. To investigate whether inhibition of Sox2 activity in early ESC differentiation is associated with Sox2-Parp1 protein-protein interactions, we induced differentiation of mouse ESCs with all-trans RA treatment. Sox2-Parp1 interactions and Parp1 PARylation were then measured at 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48 h. Fig. 3A demonstrates that Sox2-Parp1 interaction (IP: Sox2; IB: Parp1) and Parp1 PARylation (IP: PAR; IB: Parp1) peak at 16 h after RA treatment. This result is consistent with our finding that PARylation is required for the binding of Sox2 with Parp1. The data in Fig. 3A also demonstrate that Sox2 levels are dramatically decreased within a few hours after maximum Sox2-PARylated Parp1 interaction. These results combined with the data in Fig. 2 suggest that inhibition of Sox2 activity by Sox2-PARylated Parp1 complexes plays an important role in the initiation of ESC differentiation.

Fig. 3.

FGF/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling induces Parp1 auto-PARylation. (A) Parp1 auto-PARylation and Sox2-Parp1 interaction upon induction of differentiation. Differentiation of wild-type ESCs was stimulated with RA. Parp1 PARylation and Sox2-Parp1 interaction were analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation at indicated time points. Protein expression was analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) Differentiation delay in Parp1/Parp2 knockdown ESCs. Parp1/Parp2 knockdown ESC lines were induced with RA for 2 d and colony morphology was visualized by light phase microscopy. The data demonstrate that Parp1/Parp2 knockdown delays ESC differentiation. (C) Inhibition of FGF signaling during RA induced differentiation inhibits Parp1 auto-PARylation and Sox2-Parp1 interaction. ESCs that were treated with or without the FGF inhibitor (PD173074) were induced to differentiate with RA. Parp1 PARylation and Sox2-Parp1 interactions were assayed by coimmunoprecipitation at 16 h post RA exposure. (D) FGF/ERK signaling activates Parp1 PARylation in steady-state ESCs. Parp1 PARylation and Parp1-Sox2 interaction were analyzed using lysates prepared from ESCs treated with mFGF4, FGF inhibitor (PD173074), MAPK inhibitor (PD0325901), and GSK3β inhibitor (CHIR99021). The data demonstrate that stimulation of FGF signaling (FGF4 treatment) enhances PARylated Parp1-Sox2 interaction and that FGF inhibitor and MAPK inhibitor treatment decreases PARylated Parp1-Sox2 interaction. Therefore, Parp1 is a key mediator of FGF signaling that regulates the balance between pluripotency and differentiation.

To further test this hypothesis, we determine whether RA-induced differentiation was reduced in Parp1, Parp2, and Parp1/Parp2 knockdown ESC lines. After treating with RA for 2 d, ESCs containing control shRNA differentiated normally and lost characteristic ESC morphology (Fig. 3B, Left). However, double-knockdown cells retained normal ESC morphology (Fig. 3B, Right). These results demonstrate that Parp1 and Parp2 are essential for normal ESC differentiation.

Auto-PARylation of Parp1 is Activated by the FGF/ERK Pathway.

We observed that Parp1 was PARylated and interacted with Sox2 relatively quickly after a differentiation stimulus (RA). This finding led us to examine whether known signal transduction pathways stimulate Sox2-Parp1 interactions and subsequent ESC differentiation. The FGF/ERK pathway plays an important role in regulating pluripotency and lineage specification by directing ESCs to exit self-renewal. RA is known to stimulate ESC differentiation through the FGF/ERK pathway (47, 48), and phosphorylation of Parp1 via Erk1/2 is known to induce Parp1 auto-PARylation (49). However, a direct link between Erk1/2 activation, Parp1 auto-PARylation, and ESC differentiation has not been described.

Therefore, we monitored Erk1/2 activity (phosphorylation status of Thr202 and Tyr204 in Erk1 and Thr185 and Tyr187 in Erk2) following RA treatment to induce ESC differentiation. Interestingly, Erk1/2 activation is observed at 8 h after exposure to RA (Fig. 3A, P-Erk1/2), just prior to the robust PARylation of Parp1 seen at 16 h. As described above (Fig. 3A, Top), maximum PARylated Parp1-Sox2 interactions occur at 16 h after RA treatment. These results suggest a direct link between Erk1/2 activation, Parp1 auto-PARylation, and ESC differentiation. This link is further substantiated by pharmacological inhibition of FGF/ERK activation during RA-induced differentiation. When ESCs are treated with RA for 16 h in the presence of the FGF inhibitor PD173074, PARylated Parp1, and Sox2-Parp1 interactions are significantly decreased (Fig. 3C).

Previous experiments have demonstrated that suppression of the FGF/ERK pathway sustains ESCs in the ground state (3). Fgf4 is the major Fgf family member that is produced by ESCs, and Fgf4 gene expression is directly regulated by Oct4 and Sox2 (8). In addition, ESCs can activate the FGF/ERK pathway in an autocrine manner via Fgf4. Therefore, we determined whether the FGF/ERK pathway controls pluripotency by mediating Parp1-Sox2 interactions. ESCs were treated with mFGF4, FGF receptor inhibitor (PD173074), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor (PD0325901), or glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK3β) inhibitor (CHIR99021), and coimmunoprecipitations were performed (Fig. 3D). We observed that Parp1 PARylation as well as Parp1-Sox2 interactions were increased by activating the FGF/ERK pathway with mFGF4 but decreased by inhibiting the FGF/ERK pathway with FGF receptor inhibitor (PD173074) or MEK inhibitor (PD0325901) (Fig. 3D). GSK3β inhibitor treatment (CHIR99021) did not change the level of Parp1 PARylation, when normalized to total Parp1, but did upregulate Parp1 and Sox2 protein expression. These results strongly suggest that the FGF/ERK pathway regulates pluripotency by mediating Parp1-Sox2 interactions.

Depletion of Parp1 and Parp2 Represses iPSC Induction.

Yamanaka and coworkers (50) first showed that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) through the forced expression of four transcription factors (4Fs) Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc, albeit with low efficiency. An optimal stoichiometry of the 4Fs must be achieved for efficient somatic reprogramming (51). Changes in relative expression levels result in significant effects. Increasing Oct4 expression enhances reprogramming efficiency; in contrast, increasing expression of Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc represses iPSC formation (52, 53). To determine whether Parp1 plays a role in iPSC generation, we first assayed Sox2-Parp1 interactions during the reprogramming process (Fig. S6A). The 4Fs were introduced into mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) by retrovirus transduction. After 2 d, virus-infected MEFs were pooled and then resplit on several culture dishes to ensure an even transduction frequency on each plate. Small ESC-like colonies began to appear at 7 d post transduction. At day 14, one plate was used for alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining to determine the number of potential iPSCs. More than 2,000 AP positive colonies were detected on one 10 cm plate, suggesting an efficient reprogramming process. Cells were collected at 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 14 d post transduction and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. Notably, expression of Parp1 was upregulated upon iPSC formation (Fig. S6B). Sox2-Parp1 interaction was first observed at day 7 and became more intense in later stages. To further determine the requirement for Parp1 in iPSC reprogramming, Parp1 and Parp2 shRNAs along with 4Fs were introduced into MEFs. Control shRNAs and shRNA against Sox2 were also used as experimental controls. The formation of iPSC colonies was determined by AP staining 14 d after transduction. Compared to the result from control shRNA, the number of AP positive colonies significantly decreased (40% of control) in the Parp1 and Parp2 knockdowns, and double-knockdown did not further reduce iPSC colony numbers. A similar result was obtained during iPSC production using Parp inhibitors (DPQ and PJ34). The number of iPSC colonies derived from PJ34-treated MEFs was decreased to 70% of the control (Fig. S6C). Our results demonstrate that Parp1, Parp2, and PARylation are required for somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs.

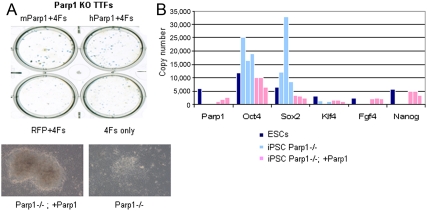

We also performed iPSC induction experiments with tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs) derived from Parp1 knockout animals (Fig. 4 A and B). The results are consistent with the Parp1 knockdown data described above. Expression analysis suggests that iPSCs derived from Parp1-/- TTFs are not fully reprogrammed because of abnormal expression of genes that are essential for pluripotency (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate a clear deficiency in Parp1-/- cells and suggest that Parp1-/- animals, from which the TTFs were derived, are not phenotypically normal.

Fig. 4.

Parp1 and Parp2 are required for iPSC reprogramming. (A) Parp1 deficiency inhibits iPSC reprogramming. Parp1-/- TTFs were transduced at day 0 with four recombinant retroviruses containing the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc. At day 3, infected TTFs were further transduced with lentivirus carrying RFP (red florescent protein), mParp1 or hParp1. At day 21, plates were stained with AP (Upper) and colony morphology (Lower) was examined by phase microscopy. (B) Parp1 deficiency results in abnormal Oct4 and Sox2 expression in iPSCs. Expression of endogenous Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, Fgf4, and Nanog in iPSC derived from Parp1-/- TTFs with and without Parp1 cDNA rescue plasmids was quantitated with the nCounter system (Nanostring Technologies). Three independent clones with and without rescue were analyzed. One wild-type ESC clone was used for the control. Expression levels are shown as copy number of RNA transcripts.

Discussion

An Auto-Regulatory Loop for Sox2 Protein.

The fate of ESCs is controlled by external signals. LIF is required for propagating mouse ESCs in an undifferentiated state. In contrast, FGFs direct ESC differentiation. Interestingly, both stimulatory and inhibitory pathways are active in ESCs; therefore, defining the points of crosstalk between these pathways is important for understanding the mechanisms involved in self-renewal and differentiation. Only recently have insights been obtained into the ways in which external factors are integrated into the core pluripotency-regulating transcriptional circuitry. By stimulating janus kinase (JAK) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3), LIF activates Klf4, which then modulates Sox2 expression. In parallel, LIF partially activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway to induce T-box 3 (Tbx3), which then directs Nanog expression (54). LIF also activates the ERK cascade to counteract the PI3K/AKT pathway (54). Additionally, Sox2 is phosphorylated by the PI3K/AKT pathway, which enhances Sox2 activity by stabilizing Sox2 protein levels (55).

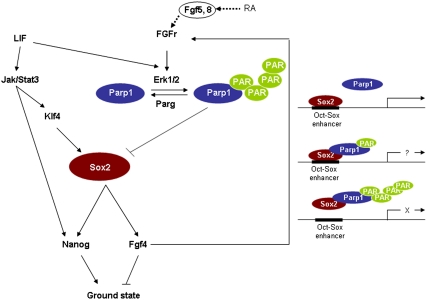

In this paper, we present a molecular map that connects the pluripotency factor Sox2 to the prodifferentiation FGF signaling pathway and the downstream ERK pathway (Fig. 5). We have identified Parp1 as a mediator of Sox2 complexes that regulate pluripotency genes such as Nanog. Although Sox2 is not PARylated, Parp1 PARylation induced by FGF signaling, and the downstream Erk1/2 pathway, influences Sox2 transactivating activity by inhibiting Sox2 recruitment to Oct-Sox enhancers. Parp1-dependent Sox2 inhibition can be rapidly reversed by Parg-mediated PAR degradation. Therefore, Parp1 PARylation provides a dynamic and efficient regulatory mechanism in ESCs. In addition, we suggest that the FGF/Parp1/Sox2 axis is employed by at least two different FGFs. In our model, Fgf8, which is induced by RA, triggers the FGF signaling pathway (48) to disassemble the enhanceosome complex composed of Oct4/Sox2/Nanog upon differentiation. This disassembly is mediated by Parp1 PARylation and subsequent Sox2/PARylated Parp1 interaction. However, in pluripotent ESCs, the FGF pathway is activated by Fgf4, which is a direct downstream target of Oct4 and Sox2. Autocrine stimulation of the FGF pathway by Fgf4 triggers Parp1 PARylation and subsequent Sox2/PARylated Parp1 complexes to inhibit overexpression of Sox2, which stimulates differentiation. Therefore, Sox2 function is fine-tuned through a protein feedback loop that is mediated by Parp1.

Fig. 5.

Model for Parp1 mediation of Sox2 activity in ESC pluripotency. In ESCs, Sox2 is preferentially activated by Klf4 in response to LIF/Jak/Stat3 signaling. On the other hand, Sox2 is negatively regulated by Parp1 auto-PARylation in response to the FGF/ERK pathway. These opposing signals maintain Sox2 at levels that optimally maintain ESC pluripotency.

Parp1 Regulates Sox2 Activity.

Interaction between Sox2 and Parp1 has previously been reported. By analyzing proteins that are bound to the FGF4 enhancer, Gao et al. (24) discovered Parp1-Sox2 interactions and concluded that Parp1 positively regulates Fgf4 expression by PARylating Sox2; the authors proposed that degradation of PARylated Sox2 relieves Sox2 repression of Fgf4. Although we confirm that Parp1 and Sox2 interact, we cannot demonstrate Sox2 PARylation. In fact, our data suggest that Parp1/Sox2 interactions are controlled by Parp1 PARylation and that Parp1 PARylation is regulated by the FGF/ERK kinase pathway. Therefore, Parp1 directly links a critical signal transduction pathway to the regulation of Sox2 target genes such as Nanog and Fgf4. Parp1 fine-tunes Sox2 activity, which is essential for maintenance of pluripotency.

In summary, our results demonstrate that Parp1 regulates Sox2 activity. In response to FGF/ERK signaling, Parp1 auto-PARylation enhances Sox2-Parp1 interactions, and this complex inhibits Sox2 binding to Oct-Sox enhancers. Based on these results, we propose a unique mechanism in which FGF signaling fine-tunes the activity of Sox2 through posttranslational modification of a critical interacting protein, Parp1, and balances the maintenance of ESC pluripotency and differentiation. In addition, we demonstrate that regulation of Sox2 by Parp1 is critical for efficient generation of iPSCs. Our data suggest that Parp1 mediates a protein feedback loop that regulates the pluripotency factor Sox2 via FGF/ERK signaling.

Experimental Procedures

ESCs were cultured as described previously (56). shRNA assays, ChIP assays, quantitative RNA analysis, and iPSC induction were performed as described in SI Text. Sox2 and Parp1 targeting vectors were constructed by recombineering as previously described (56). For affinity purification, mass spectrometry, and protein identification, nuclear extracts derived from 10E9 Sox2/FLAG/HA ESCs were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) at 4 °C for 16 h. The beads were washed and proteins eluted with 500 μg/mL 3XFLAG peptide (Sigma) in elution buffer. Protein complexes were separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and stained with a SilverQuest staining kit (Invitrogen). Each protein band was excised and subjected to high-resolution LC-LTQ FT MS/MS analysis as previously described (57, 58). Sox2/FLAG/HA ESC IPs were compared to wild-type IPs to eliminate background proteins.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. G.Q.D. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1108595109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Smith AG, et al. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–690. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols J, Silva J, Roode M, Smith A. Suppression of Erk signalling promotes ground state pluripotency in the mouse embryo. Development. 2009;136:3215–3222. doi: 10.1242/dev.038893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunath T, et al. FGF stimulation of the Erk1/2 signalling cascade triggers transition of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from self-renewal to lineage commitment. Development. 2007;134:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.02880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols J, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catena R, et al. Conserved POU binding DNA sites in the Sox2 upstream enhancer regulate gene expression in embryonic and neural stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41846–41857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405514200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers I, et al. Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2003;113:643–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan H, Corbi N, Basilico C, Dailey L. Developmental-specific activity of the FGF-4 enhancer requires the synergistic action of Sox2 and Oct-3. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2635–2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodda DJ, et al. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24731–24737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuroda T, et al. Octamer and Sox elements are required for transcriptional cis regulation of Nanog gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2475–2485. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2475-2485.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chew JL, et al. Reciprocal transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1 and Sox2 via the Oct4/Sox2 complex in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6031–6046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6031-6046.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orkin SH, et al. The transcriptional network controlling pluripotency in ES cells. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:195–202. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.72.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers I, Tomlinson SR. The transcriptional foundation of pluripotency. Development. 2009;136:2311–2322. doi: 10.1242/dev.024398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouyang Z, Zhou Q, Wong WH. ChIP-Seq of transcription factors predicts absolute and differential gene expression in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21521–21526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904863106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez RT, et al. Manipulation of OCT4 levels in human embryonic stem cells results in induction of differential cell types. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:1368–1380. doi: 10.3181/0703-RM-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boer B, et al. Elevating the levels of Sox2 in embryonal carcinoma cells and embryonic stem cells inhibits the expression of Sox2 : Oct-3/4 target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1773–1786. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopp JL, Ormsbee BD, Desler M, Rizzino A. Small increases in the level of Sox2 trigger the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:903–911. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernadt CT, Nowling T, Rizzino A. Transcription factor Sox-2 inhibits co-activator stimulated transcription. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;69:260–267. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chickarmane V, et al. Transcriptional dynamics of the embryonic stem cell switch. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heng JC, Ng HH. Transcriptional regulation in embryonic stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;695:76–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7037-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan G, et al. A negative feedback loop of transcription factors that controls stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal. FASEB J. 2006;20:1730–1732. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5543fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao F, Kwon SW, Zhao Y, Jin Y. PARP1 poly(ADP-ribosyl)ates Sox2 to control Sox2 protein levels and FGF4 expression during embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22263–22273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ame JC, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. The PARP superfamily. BioEssays. 2004;26:882–893. doi: 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishnakumar R, Kraus WL. The PARP side of the nucleus: Molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Mol Cell. 2010;39:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarez-Gonzalez R, Jacobson MK. Characterization of polymers of adenosine diphosphate ribose generated in vitro and in vivo. Biochemistry. 1987;26:3218–3224. doi: 10.1021/bi00385a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Althaus FR, Richter C. ADP-ribosylation of proteins. Enzymology and biological significance. Mol Biol Biochem Biophys. 1987;37:1–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dantzer F, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity is not affected in ataxia telangiectasia cells and knockout mice. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:177–180. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satoh MS, Lindahl T. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature. 1992;356:356–358. doi: 10.1038/356356a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caiafa P, Guastafierro T, Zampieri M. Epigenetics: Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP-1 regulates genomic methylation patterns. FASEB J. 2009;23:672–678. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-123265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) signals to mitochondrial AIF: A key event in parthanatos. Exp Neurol. 2009;218:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ame JC, et al. PARP-2, A novel mammalian DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17860–17868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shieh WM, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase null mouse cells synthesize ADP-ribose polymers. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30069–30072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang ZQ, et al. Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease. Genes Dev. 1995;9:509–520. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menissier de Murcia J, et al. Functional interaction between PARP-1 and PARP-2 in chromosome stability and embryonic development in mouse. EMBO J. 2003;22:2255–2263. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schreiber V, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 (PARP-2) is required for efficient base excision DNA repair in association with PARP-1 and XRCC1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23028–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogino H, et al. Loss of Parp-1 affects gene expression profile in a genome-wide manner in ES cells and liver cells. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnakumar R, et al. Reciprocal binding of PARP-1 and histone H1 at promoters specifies transcriptional outcomes. Science. 2008;319:819–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1149250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tulin A, Stewart D, Spradling AC. The Drosophila heterochromatic gene encoding poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is required to modulate chromatin structure during development. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2108–2119. doi: 10.1101/gad.1003902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim MY, et al. NAD+-dependent modulation of chromatin structure and transcription by nucleosome binding properties of PARP-1. Cell. 2004;119:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1: ‘PAR-laying’ NAD+ into a nuclear signal. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1951–1967. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Amours D, Desnoyers S, D’Silva I, Poirier GG. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J. 1999;342:249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leppard JB, Dong Z, Mackey ZB, Tomkinson AE. Physical and functional interaction between DNA ligase IIIalpha and poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 in DNA single-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5919–5927. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5919-5927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heale JT, et al. Condensin I interacts with the PARP-1-XRCC1 complex and functions in DNA single-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2006;21:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ju BG, et al. Activating the PARP-1 sensor component of the groucho/TLE1 corepressor complex mediates a CaMKinase IIdelta-dependent neurogenic gene activation pathway. Cell. 2004;119:815–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu J, et al. All-trans retinoic acid promotes neural lineage entry by pluripotent embryonic stem cells via multiple pathways. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stavridis MP, Collins BJ, Storey KG. Retinoic acid orchestrates fibroblast growth factor signalling to drive embryonic stem cell differentiation. Development. 2010;137:881–890. doi: 10.1242/dev.043117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kauppinen TM, et al. Direct phosphorylation and regulation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 by extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7136–7141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanna J, et al. Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature. 2009;462:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nature08592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaguchi S, Hirano K, Nagata S, Tada T. Sox2 expression effects on direct reprogramming efficiency as determined by alternative somatic cell fate. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papapetrou EP, et al. Stoichiometric and temporal requirements of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc expression for efficient human iPSC induction and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12759–12764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904825106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niwa H, Ogawa K, Shimosato D, Adachi K. A parallel circuit of LIF signalling pathways maintains pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Nature. 2009;460:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature08113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeong CH, et al. Phosphorylation of Sox2 cooperates in reprogramming to pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2141–2150. doi: 10.1002/stem.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou D, et al. Rapid tagging of endogenous mouse genes by recombineering and ES cell complementation of tetraploid blastocysts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joo HY, et al. Regulation of histone H2A and H2B deubiquitination and Xenopus development by USP12 and USP46. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7190–7201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eliuk SM, et al. Active site modifications of the brain isoform of creatine kinase by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal correlate with reduced enzyme activity: Mapping of modified sites by Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1260–1268. doi: 10.1021/tx7000948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.