Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) is an archetypical kinase and a central regulator that drives cells through G2 phase and mitosis. Knockouts of Cdk2, Cdk3, Cdk4, or Cdk6 have resulted in viable mice, but the in vivo functions of Cdk1 have not been fully explored in mammals. Here we have generated a conditional-knockout mouse model to study the functions of Cdk1 in vivo. Ablation of Cdk1 leads to arrest of embryonic development around the blastocyst stage. Interestingly, liver-specific deletion of Cdk1 is well tolerated, and liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy is not impaired, indicating that regeneration can be driven by cell growth without cell division. The loss of Cdk1 does not affect S phase progression but results in DNA re-replication because of an increase in Cdk2/cyclin A2 activity. Unlike other Cdks, loss of Cdk1 in the liver confers complete resistance against tumorigenesis induced by activated Ras and silencing of p53.

Keywords: cancer, knockout mice, cell cycle regulation, polyploidy

The activities of cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) control all aspects of cell division, including entry into the cell cycle from quiescence, the G1/S phase transition, DNA replication in S phase, nuclear breakdown, chromosome condensation and segregation, and cytokinesis (1). The mammalian genome contains at least 20 different Cdks, and widespread compensation among Cdks and cyclins has been reported (2, 3). Cdk1 was the first Cdk identified (4, 5), is conserved in all organisms, plays important roles in mitosis, and can drive S phase in the absence of Cdk2 (6). Mouse knockouts of Cdk2 (7, 8), Cdk3 (9), Cdk4 (10, 11), or Cdk6 (12, 13) are viable, indicating that any single Cdk independently is not essential for survival of mice. Interestingly, double knockouts of Cdk2/Cdk4 (14) and Cdk4/Cdk6 (13) but not Cdk2/Cdk6 (13) are embryonic lethal, suggesting genetic interactions. Therefore, Cdk2 and Cdk4 (as well as Cdk4 and Cdk6) display overlapping functions and can substitute for each other (3, 15). In the absence of Cdk2 and Cdk4, we have demonstrated an accumulation of hypophosphorylated Retinoblastoma protein (Rb), which represses E2F-mediated transcription leading to decreased expression of E2F-target genes like Cdk1 and others (14).

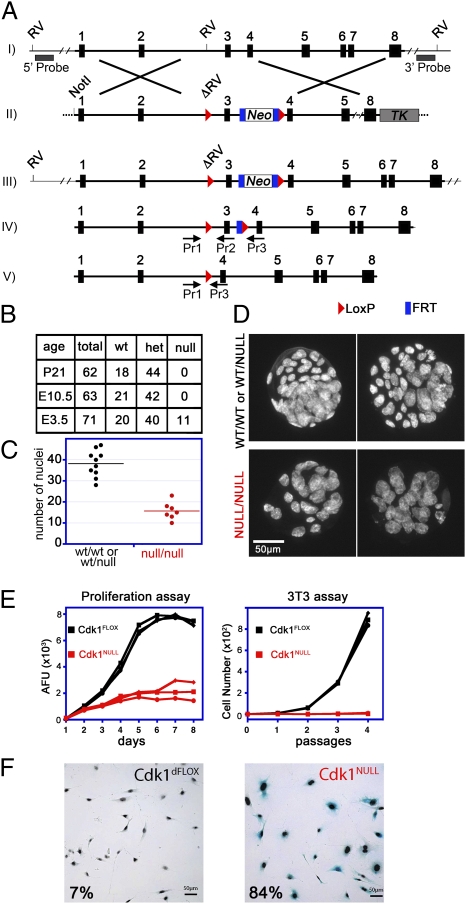

Constitutive gene disruption mutations in the Cdk1 locus have been reported, but neither of these approaches yielded homozygous Cdk1NULL cells or tissues for further analysis (16, 17). To study the in vivo functions of Cdk1, tissue specificity, and requirement in adult mice, we have generated conditional knockout mice by inserting LoxP sites on both sides of exon 3 in the Cdk1 locus (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1 A and B).

Fig. 1.

Generation and analysis of Cdk1 conditional knockout mice and cells. (A) The Cdk1 genomic locus (I) was modified in ES cells with the targeting vector (II) shown. An FRT-flanked neomycin-selection cassette was introduced along with LoxP recombination sites (red triangles) on both sides of exon 3, which generated a mutant Cdk1 locus (III). For Southern blot analysis, 5′ and 3′ probes located outside of the targeting vector were used, after an EcoRV (RV) digest, resulting in a 31,206-bp (recombinant) and a 9,110-bp (5′) or 20,300-bp (3′) fragment for wild type (Fig. S1A). Upon expression of FLP recombinase, the neomycin cassette was removed, and only the LoxP sites remained in the locus (IV, Cdk1FLOX). The levels of Cdk1 protein expression were similar in Cdk1FLOX and Cdk1WT mice (Fig. S1B). After Cre recombinase expression, exon 3 was excised (V), which resulted in deletion of Cdk1 and a frame shift. PCR genotyping primers are indicated (Pr1, -2, and -3), and the sequences can be found in Table S1. (B) To generate Cdk1 knockouts, Cdk1FLOX mice were crossed with β-actin–Cre mice expressing Cre recombinase ubiquitously in all tissues, including germ line. The resulting Cdk1WT/NULL mice were interbred, and the offspring was analyzed at weaning (P21), midgestation (E10.5), or blastocyst (E3.5) stage. (C and D) Cdk1NULL/NULL blastocysts were visualized by Hoechst staining of their nuclei followed by fluorescence microscopy. Comparison of Cdk1-deficient blastocysts with heterozygous or wild-type littermates indicated a reduced number of cells (C); however, their nuclei were larger in size (D). (E and F) Three independent MEF lines (Fig. S1 C–H) were treated with 4-OHT to induce Cdk1 knockout, and their proliferative potential was monitored by 3T3 and alamarBlue proliferation assays for several passages or days, respectively (E). Deletion of Cdk1 resulted in a rapid arrest of cellular proliferation and premature onset of cellular senescence that was detected by senescence-associated β-gal staining (F). Therefore, cells lacking Cdk1 cannot proliferate but instead enter a senescent state and survive in culture medium.

Results

Cdk1 Is Essential for Cellular Proliferation and Early Embryonic Development.

To investigate the effects of loss of Cdk1 in mouse development, we crossed Cdk1+/NULL animals with each other and monitored the progeny at postnatal day 21 (P21), embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5), and E3.5. We could not detect viable homozygous knockout mice or embryos at P21 or E10.5, indicating that Cdk1 is an essential gene for early embryonic development. However, genotyping of blastocysts at E3.5 revealed that 16% were homozygous knockout, 56% heterozygous, and 28% wild type for the Cdk1 locus (Fig. 1B). Detailed analysis of Cdk1NULL blastocysts by microscopy revealed that they had a reduced number of nuclei, which were larger in size compared with wild-type and heterozygous littermates (Fig. 1 C and D). The first few cells divisions in Cdk1-deficient embryos are possibly achieved because of the presence of maternally deposited Cdk1 mRNA in the oocytes (18). After the maternally provided mRNA runs out, cells of the Cdk1NULL embryos were not able to divide anymore, which suggests Cdk1 is essential for cell division in early-stage embryos.

To confirm that Cdk1 is essential for cell proliferation, we turned to primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), in which we could induce the loss of Cdk1 by addition of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) (Fig. S1 C–H). When these MEFs were analyzed for proliferation by using techniques such as alamarBlue or 3T3 assays, Cdk1NULL MEFs did not increase in numbers but entered senescence prematurely, demonstrating that Cdk1 is essential for cell proliferation (Fig. 1 E and F).

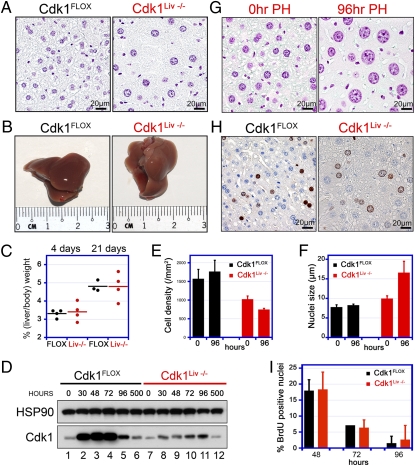

Liver Regeneration in the Absence of Cell Division.

Because of the embryonic lethality, we generated mice that were specifically targeted to ablate the expression of Cdk1 in the liver (hepatocytes; Cdk1FLOX/FLOX mice expressing the albumin-Cre transgene, referred to as Cdk1Liv−/−). We chose the liver as an in vivo model system because hepatocytes rarely divide in adult animals unless regeneration is induced by partial hepatectomy (PH; ref. 19 and below). Albumin-Cre expression starts during embryonic development but only reaches sufficiently high levels to cause efficient recombination approximately 3 wk after birth (20), a time when liver development and hematopoiesis are already completed. Cdk1Liv−/− mice were viable and did not display any adverse phenotypes. We prepared Feulgen-stained sections of Cdk1Liv−/− and control livers (Fig. 2A). The diameter of the Cdk1Liv−/− nuclei was increased by 28%, and the cell density was decreased by 35%. To force hepatocytes to reenter the cell cycle, we subjected Cdk1Liv−/− mice to 70% PH. Interestingly, PH in both wild-type and Cdk1Liv−/− mice led to complete regeneration of liver mass within 3 wk (Fig. 2 B and C). However, Cdk1-deficient hepatocytes were unable to enter mitosis (Fig. S2), indicating that liver regeneration can be achieved by cell growth in the absence of cell division. PH induced expression of Cdk1 in control but not in Cdk1Liv−/− animals (Fig. 2D; note that the Cdk1 band in lanes 7–12 originates from liver cells other than hepatocytes). In control mice, the cell density and nuclear diameter did not change significantly by 96 h after PH (Fig. 2 E and F). In contrast, we measured a 27% decrease in cell density (Fig. 2 E and G) and a 67% increase in nuclear diameter (Fig. 2 F and G), which is consistent with ablated cell division and a substantial increase in cell growth in Cdk1Liv−/− mice. As a measure of DNA replication after PH, we determined BrdU incorporation and detected a peak at 48 h after PH (Fig. 2 H and I), which is consistent with published results (21). Cdk1Liv−/− livers displayed BrdU incorporation rates similar to those of wild type, and therefore we hypothesized that Cdk1Liv−/− cells must be able to undergo some form of DNA replication.

Fig. 2.

Liver-specific knockout of Cdk1. (A) Liver sections from Cdk1Liv−/− and control mice were stained with Feulgen to visualize their nuclei. Even though the overall liver size was similar, Cdk1-knockout livers contained fewer hepatocytes with enlarged nuclei. (B and C) To analyze the regenerative potential and S phase entry in Cdk1-knockout livers, 70% of the liver mass was removed by PH. Animals were euthanized 4 or 21 d later, and the ratio of liver to body weight was determined. Each dot in the chart represents an individual PH experiment, and mean values are depicted by the black or red lines. Cdk1Liv−/− livers regenerated the lost mass within 3 wk, comparable to controls. (D) To confirm Cdk1 knockout, Western blots with Cdk1 antibodies were performed at different times after PH in control and Cdk1Liv−/− liver extracts. Cdk1 expression detected in knockout livers is due to liver cells other than hepatocytes. (E–G) Cdk1Liv−/− display a decreased hepatocyte density compared with controls and the difference is exacerbated by 96 h after PH (E). Cdk1Liv−/− hepatocytes have enlarged nuclei that become even bigger after PH (F and G). (H and I) Regenerating livers were pulse-labeled with BrdU at 48 (H), 72, and 96 h after PH. BrdU incorporation was detected by immunohistochemical staining of liver sections (H) and quantified with a custom developed image analysis software (I). Data were obtained from n = 3 animals in E, F, and I and are represented as mean ± SD. Black and red bars indicate Cdk1FLOX and Cdk1Liv−/− livers, respectively.

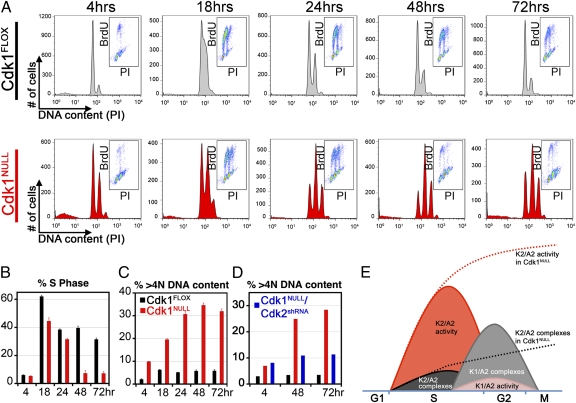

Cdk1 Is Dispensable for DNA Replication but Regulates Cdk2 Activity to Suppress DNA Re-replication.

DNA replication in S phase is promoted by Cdk2 in complex with cyclins E and A2 (22). However, there are no detectable replicative deficiencies in Cdk2-knockout mice because Cdk1 can fully compensate for the absence of Cdk2 (6–8). To further investigate whether Cdk1 activity is required for initiation and progression of DNA replication in presence of Cdk2, we turned to our conditional knockout primary MEFs, in which we can study cell-cycle progression kinetics in a controlled fashion (Fig. S1 C and D).

MEFs were synchronized in the G0/G1 phase by serum starvation, and Cdk1 knockout was simultaneously induced by addition of 4-OHT. After synchronization, MEFs were released into S phase in the presence of serum and labeled by BrdU as a measure for DNA replication. During the first cell cycle, Cdk1NULL cells progressed through S phase like wild-type MEFs did (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S3). Therefore, the loss of Cdk1 does not affect S phase progression in the presence of wild-type Cdk2. However, Cdk1NULL MEFs cannot initiate early events of mitotic entry such as cytoskeletal reorganization and rounding up of the cell body (Fig. S1H) and therefore arrest in G2 without entering mitosis.

Fig. 3.

Cdk1 is redundant for S phase progression, but its loss results in endoreduplication. (A) Cdk1FLOX MEFs were synchronized in the G0/G1 phase by serum starvation for 72 h and simultaneously treated with 4-OHT to induce knockout of Cdk1. They were then released into S phase by addition of serum, pulse-labeled with BrdU, and analyzed by FACS to determine the percentage of cells in S, G1, and G2 phases. Histograms depict the distribution of DNA content as detected by propidium iodide (PI) staining. Insets show the distribution of BrdU incorporation (BrdU) versus DNA content (PI) within the same population. Three independent experiments were performed with three different clones. (B) Quantitative analysis of cells in S phases of the cell cycle are shown. Although Cdk1-knockout MEFs seem to have a slightly reduced ratio in S phase at 18 and 24 h, this is due to the accumulation of G2-arrested cells during the serum starvation period, which cannot enter S phase as efficiently as G1 cells. Data are represented as mean ± SD. (C) Deletion of Cdk1 resulted in endoreduplication and accumulation of cells with a DNA content greater than 4N. (D) However, simultaneous removal of Cdk2 with shRNAs partially rescued the endoreduplication phenotype. See also Fig. S3. (E) A model demonstrating how Cdk1 manages to reduce Cdk2 activity at the end of S phase and prevents DNA re-replication. According to our model, kinase activity of Cdk2/cyclin A2 complexes is higher than that of Cdk1/cyclin A2 complexes. Cyclin A2-associated kinase activity peaks in S phase. However, increased levels of Cdk1 protein during late S to early G2 phase results in fewer cyclin A2 molecules available for binding to Cdk2. As a result, Cdk1 quenches cyclin A2-associated kinase activity. In Cdk1-deficient cells (represented by dashed lines), cyclin A2 molecules are forming complexes only with Cdk2. Therefore, Cdk2/cyclin A2 kinase activity cannot be suppressed and persists throughout G2 phase.

A detailed analysis of the FACS data indicated an additional 8N peak, suggesting DNA re-replication in the absence of cell division (Fig. 3C). We found that ∼30% of the Cdk1-deficient cells had undergone DNA re-replication, compared with 6% in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 3C). Simultaneous knockdown of Cdk2 in Cdk1NULL cells significantly reduced re-replication (Fig. 3D), suggesting that Cdk2 substantially contributed to DNA re-replication.

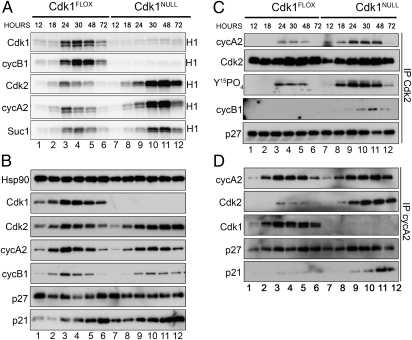

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of re-replication, we measured the kinase activity after immunoprecipitating Cdks or cyclins. In Cdk1FLOX cells (these are essentially wild-type cells), all activities peaked in the 24- to 48-h range (Fig. 4A, lanes 1–6; for quantitative analysis of kinase activities, see Fig. S4). In contrast, there was no detectable Cdk1 or cyclin B1-associated kinase activity at any of the time points in Cdk1NULL cells (Fig. 4A, top two gels, lanes 7–12). This finding suggests that cyclin B1 does not form active complexes with Cdk2 despite its increased association in Cdk1NULL cells (Fig. 4C and Fig. S4B). Interestingly, Cdk2 or cyclin A2-associated kinase activities were elevated compared with control and extended from 18 to 72 h (Fig. 4A, third and fourth gels from the top, lanes 8–12). This result indicates that Cdk1 might be responsible for suppressing Cdk2/cyclin A2 kinase activity at the end of S phase in wild-type cells, which prevents re-replication from occurring and was confirmed by silencing of Cdk2 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 4.

Increased Cdk2 kinase activity in Cdk1-deficient MEFs. (A) To analyze the kinase activities associated with Cdks and cyclins, protein extracts were prepared from cells in Fig. 3 at different time points and subjected to immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies followed by in vitro kinase assays using radiolabeled ATP and histone H1 as substrates. Cdk2 and cyclin A2-associated kinase activities were significantly increased in Cdk1-deficient cells. (B) Samples from A were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (C and D) To analyze the Cdk2/cyclinA2 complexes, protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against Cdk2 (C) or cyclin A2 (D) followed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. See also Figs. S4–S6 and S8.

The increased Cdk2 activity in the absence of Cdk1 could be caused by several factors, including decreased binding of Cdk inhibitors, decreased inhibitory phosphorylation, increased Cdk2 or cyclin A2 expression (increased transcription or decreased degradation), increased Cdk complex formation, or differential activity of Cdk2/cyclin A2 and Cdk1/cyclin A2 complexes. We tested all these possibilities and conclude that the latter two possibilities contributed significantly to the increase of Cdk2/cyclin A2 activity in the absence of Cdk1 (as described below). The mRNA levels of Cdk2, cyclin A2, and many other cell-cycle–related genes were comparable between Cdk1NULL and Cdk1FLOX cells. As expected, the Cdk1 mRNA was almost undetectable after deletion of Cdk1 (Fig. S7). The protein levels of Cdk2 and cyclin A2 were similar in the absence of Cdk1 compared with control cells (Fig. 4B), and therefore changes in protein synthesis or degradation were not causing the increase in Cdk2/cyclin A2 activity. In addition, the levels of p21 and p27 were marginally increased in the absence of Cdk1 (Fig. 4B). We also analyzed the inhibitory phosphorylation (Y15PO4) on Cdk2 and observed an increase of tyrosine 15 phosphorylation per molecule of Cdk2 in the absence of Cdk1 (Fig. 4C). Analysis of Cdk inhibitor binding to either Cdk2 (Fig. 4C) or cyclin A2 (Fig. 4D) did not reveal a difference for p27. However, we observed a slightly increased binding of p21 in the Cdk1NULL cells compared with control cells, which would have an inhibitory effect on the kinase activity. Finally, we determined the number of Cdk2/cyclin A2 complexes [either immunoprecipitated Cdk2/Western-blotted cyclin A2 (Fig. 4C) or immunoprecipitated cyclin A2/Western-blotted Cdk2 (Fig. 4D)] and detected a substantial increase in the absence of Cdk1. The increased number of Cdk2/cyclin A2 complexes is consistent with the increased kinase activity observed (Fig. 4A). Because more cyclin A2 molecules are binding to Cdk2 in the absence of Cdk1, most likely the majority of the cyclin A2 molecules are bound to Cdk1 in wild-type cells. Thus, it appears that, as cells progress through S phase, cyclin A2 initially forms complexes with Cdk2, and, later, most cyclin A2 molecules are bound to Cdk1 (Fig. 3E). Cdk2/cyclin A2 activity needs to be inhibited after S phase to prevent re-replication (Fig. 3E). Thus, we hypothesize that, to achieve this inhibition, the specific kinase activity of Cdk1/cyclin A2 is different from Cdk2/cyclin A2. Therefore, we determined the kinetic parameters of these Cdk complexes with purified proteins and found that the Km (histone H1) for Cdk1/cyclin A2 is about two times lower and the Vmax (histone H1) is approximately eight times lower than Cdk2/cyclin A2 (Fig. S8A and B). The activity of Cdk1/cyclin A2 complexes is very low compared with Cdk2/cyclin A2, thus effectively resulting in suppression of the Cdk2 activity at the end of S phase to prevent re-replication. This finding was corroborated by experiments in Cdk2NULL MEFs, in which the cyclin A2-associated kinase activity resulting exclusively from Cdk1/cyclin A2 complexes was substantially lower compared with wild-type cells (Fig. S6). The re-replication phenotype that we uncovered in MEFs is most likely the reason for the increased polyploidy after PH in Cdk1Liv−/− livers (Fig. 2).

Tumorigenesis Requires Cdk1 Activity.

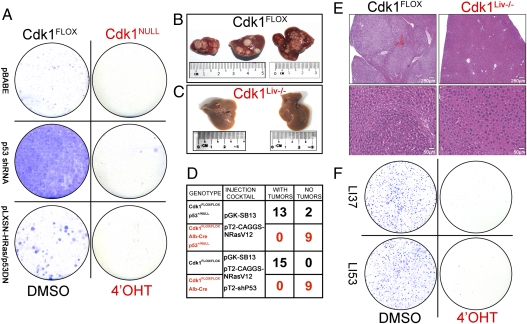

Analysis of human tumor samples revealed that expression of several Cdks and cyclins are often up-regulated (23). However, gene-knockout studies by us and others (2, 15, 24) have indicated that none of the previously tested Cdks can completely prevent tumorigenesis. Therefore, we determined whether the loss of Cdk1 prevents cellular transformation and tumor development in vivo. First, we tested the effect of loss of Cdk1 on cell transformation. Expression of activated Ras and dominant-negative p53 or shRNA against p53 resulted in substantial increases in cell proliferation and transformed colonies in control MEFs (Fig. 5A). In cells treated with 4-OHT to induce the loss of Cdk1, few colonies were observed. In addition, the few colonies that were detected expressed Cdk1 because of lack of full recombination. Therefore, we concluded that cell proliferation in transformed cells depends on Cdk1.

Fig. 5.

Oncogenic transformation or tumorigenesis is not possible in the absence of Cdk1. (A) Cdk1FLOX MEFs were immortalized or transformed with p53 shRNA or activated Ras/p53DN, respectively. Colony-formation assays after induction of the cells with 4-OHT indicate that Cdk1-deficient cells cannot be immortalized or transformed. (B–E) Liver tumors were induced by tail-vein injection of activated Ras (B), but no tumors were detected in Cdk1Liv−/− livers (C). Quantitative analysis of liver tumors in mice of the indicated genotypes (D) is shown. Histological sections of the liver were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (E) to demonstrate normal morphology in the Cdk1Liv−/− (Right) and many tumors in control livers (Left). (F) Tumors from two different Cdk1FLOX/FLOX mice (LI37 and LI53) were isolated, dissociated, and grown in culture. After introduction of CreERT2 and treatment with DMSO (control) or 4-OHT, cells were subjected to a colony-formation assay followed by Giemsa staining.

To investigate tumor formation in vivo, we used tail-vein injections of activated Ras alone (in a p53+/− background) or in combination with an shRNA to silence p53 expression (25). Control mice (Cdk1FLOX/FLOX) developed many liver tumors within 3–4 mo (Fig. 5 B, D, and E). In contrast, none of the Cdk1Liv−/− (Cdk1FLOX/FLOX; albumin-Cre) mice developed tumors, even after aging them up to 9 mo (Fig. 5 C, D, and E). Only one of the Cdk1 liver-knockout animals developed liver tumors, but further analysis by genotyping of the tumor samples revealed incomplete Cdk1 knockout. Histopathological analysis indicated that Cdk1Liv−/− livers appeared similar to livers from untreated mice, whereas massive tumors and frequent neoplasia were detected in control mice (Fig. 5E).

To analyze tumor cells in vitro, we isolated them from Cdk1FLOX/FLOX liver tumors. These primary liver tumor cells grew well (Fig. S9A) and were able to form colonies (Fig. 5F, Left). We infected these cells with a retrovirus encoding CreERT2 and treated them with 4-OHT to induce the loss of Cdk1 (Fig. S9B). After 4-OHT treatment, these Cdk1NULL cells were not able to form any colonies (Fig. 5F, Right). Identical experiments were performed with the Cdk1-specific inhibitor RO-3306 (26) and roscovitine (a general Cdk inhibitor) instead of 4-OHT, and comparable results were obtained (Fig. S9C). Cdk1-deficient tumor cells rapidly became senescent (Fig. S9D), as we had previously observed for MEFs (Fig. 1F). Our results indicate that Cdk1 is required for the growth of liver tumors in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

Previous work has suggested that Cdk2, Cdk4, or Cdk6 are not essential to complete a full cell division cycle. Cdk1 can compensate for their combined loss by forming active complexes with A-, B-, E-, and D-type cyclins (6, 24, 27). Because constitutive inactivation of the Cdk1 locus led to early embryonic lethality, we had to resolve to generate a conditional knockout mouse model for detailed analysis of loss of Cdk1.

Here we demonstrate that, although Cdk1 is essential for cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, it is not required for DNA replication and liver regeneration. Earlier studies wherein Cdk1 activity was targeted by different methods such as knock-in of a temperature-sensitive allele in human cells (28), selective drug inhibitors (26), or RNAi-mediated silencing (29) have shown that loss or inhibition of Cdk1 activity results in DNA re-replication, polyploidy, and cellular senescence but only in transformed cell lines in vitro. We extended these findings in vivo and uncovered a molecular mechanism by which Cdk1 suppresses re-replication through inhibition of Cdk2 activity by sequestering cyclin A2 molecules into low-activity complexes (Fig. 3E). This finding is valid not only for MEFs but also in liver tumor cells (Fig. S5), and therefore represents an additional layer of regulation of Cdk activities during the cell cycle.

Cdk1 and Re-replication.

Cdks have pleiotropic roles in initiation of S phase entry and prevention of re-replication after DNA synthesis has been completed. Although Cdk-independent mechanisms exist to avoid refiring of replication origins (30), coupling of the whole process with the cell cycle requires sequential activation of Cdk2 and Cdk1 to initiate origin firing and ensuring that it takes place only once per cycle.

Cdk1 activity during mitosis is essential for preventing the re-replication. Inhibition of Cdk1 activity via mutagenesis (28, 31) or selective drug inhibitors (26) has been shown to result in increased endoreduplication. Corroborating this hypothesis, p57-mediated inhibition of Cdk1 activity in an endogenous system, trophoblast giant cells, has been shown to be essential for repeated rounds of endoreduplication that take place during their maturation (32); in the same system, the authors have also shown that Cdk2 is required for endoreduplication.

In our current work, we demonstrate that Cdk1-deficient primary MEFs and hepatocytes are more likely to undergo endoreduplication compared with controls. Simultaneous inactivation of Cdk2 by RNAi in Cdk1NULL MEFs reverted the re-replication phenotype. We propose a mechanism to explain why Cdk1-deficient cells endoreduplicate their genomes and how Cdk1 suppresses Cdk2 activity at the end of S phase to aid prevention of replication-origin refiring (Fig. 3E).

Cdk1 and Tumorigenesis.

We have demonstrated that MEFs cannot be transformed after deletion of Cdk1. Validation of these results in vivo proved that liver tumors do not form in absence of Cdk1. Because Cdk1 seems to be essential for proliferation in each and every cell and tissue type tested, its inactivation would prevent formation and propagation of tumors. This finding is in contrast to other Cdks, whose inactivation had little effect on tumor formation (6, 24, 33). Therefore, our results indicate the potential of Cdk1 inhibitors in cancer therapy if we can prevent the detrimental side effects resulting from unintentionally interfering with the essential functions of Cdk1 in proliferative tissues.

Materials and Methods

SI Materials and Methods include details on primers, genotyping, real-time PCR, Cdk1 conditional knockout mice and other transgenic lines, blastocyst isolation, Western blot analysis, immunoprecipitation, kinase assays, cell culture, FACS analysis, PH, and image analysis.

Generation of Cdk1 Conditional Knockout Mice.

Mouse genomic DNA harboring the Cdk1 locus was isolated from the BAC clone 305J21 (ResGen). Using recombineering technique (34), LoxP recombination sites and a neomycin-selection cassette were introduced flanking the third coding exon of the mouse Cdk1 genomic locus. The resulting targeting vector was linearized by NotI digestion, and ES cells were electroporated. After positive and negative selection with Geneticin and ganciclovir, respectively, genomic DNA of surviving ES cell colonies were screened for homologous recombination by Southern hybridization (Fig. S1A). Correctly targeted ES cell clones were identified and used for the generation of the Cdk1 conditional knockout mouse strain.

Isolation and Culture of Primary MEFs.

Primary MEFs were isolated from E13.5 mouse embryos as described previously (7). Briefly, the head and the visceral organs were removed, the embryonic tissue was chopped into fine pieces with a razor blade and trypsinized for 15 min at 37 °C, and finally tissue and cell clumps were dissociated by pipetting. Cells were plated in a 10-cm culture dish (passage 0) and grown in DMEM (12701-017; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS (26140; Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (15140-122; Invitrogen). Primary MEFs were cultured in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 3% O2.

Tail-Vein Injections and Liver Tumorigenesis.

Hydrodynamic tail-vein injections and Sleeping Beauty transposon-induced liver tumorigenesis were performed as described previously (25, 35). Six- to 10-wk-old mice were injected with a plasmid mixture diluted in lactated Ringer's solution. Animals were injected with a volume corresponding to 10% of their body weight (i.e., 2 mL for a 20-g mouse, not exceeding 2.5 mL) through their lateral tail vein within 8–10 s using 27-gauge needles. Plasmids encoding 12.5 μg of transposase (pGK-SleepingBeauty13) and a total of 25 μg of transposon (pT2-Caggs-NRasV12 and pT2-sh p53) were injected per animal. Plasmid DNA used for injection was purified with the Qiagen EndoFree Plasmid Maxi Kit (12362). Control mice (those expressing Cdk1 in their livers) were euthanized when moribund (usually within 3–4 mo) or kept for a maximum of 6 mo. Test animals (those that are Cdk1 knockout in their livers) were kept for a maximum of 9 mo before euthanizing for histological analysis. All animal experiments were done in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eileen Southon and Susan Reid for help in generating the Cdk1FLOX/FLOX mice, and David Largaespada for transposase/transposon constructs. We appreciate that Jos Jonkers and Anton Berns provided the ROSA26-CreERT2 mice, Andy McMahon the Cre-Esr1 mice, Mark Lewandoski the β-actin–Cre/Flpe mice, and T. Jake Liang the albumin-Cre mice. We thank Nancy Jenkins and Neal Copeland for advice, suggestions, reagents, and support. We are thankful to Cyril Berthet for reagents and discussion as well as to Steve Cohen and Neal Copeland for comments on the manuscript. We also thank Davor Solter and Barbara Knowles for technical advice; June Wang, Chloe Sim, and Vithya Anantaraja for animal care; Keith Rogers, Susan Rogers, and the technicians of the Pathology/Histotechnology Laboratory for superb analysis of mouse pathology; and the P.K. laboratory for support and discussions. This work was supported by the Biomedical Research Council of the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A*STAR), Singapore.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1115201109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Morgan DO. The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control. London: New Science Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satyanarayana A, Kaldis P. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: Several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene. 2009;28:2925–2939. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohka MJ, Hayes MK, Maller JL. Purification of maturation-promoting factor, an intracellular regulator of early mitotic events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3009–3013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurse P, Thuriaux P. Regulatory genes controlling mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1980;96:627–637. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aleem E, Kiyokawa H, Kaldis P. Cdc2-cyclin E complexes regulate the G1/S phase transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:831–836. doi: 10.1038/ncb1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthet C, Aleem E, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Kaldis P. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1775–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega S, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye X, Zhu C, Harper JW. A premature-termination mutation in the Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 3 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1682–1686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041596198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rane SG, et al. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in β-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat Genet. 1999;22:44–52. doi: 10.1038/8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsutsui T, et al. Targeted disruption of CDK4 delays cell cycle entry with enhanced p27Kip1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7011–7019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu MG, et al. A requirement for cyclin-dependent kinase 6 in thymocyte development and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:810–818. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malumbres M, et al. Mammalian cells cycle without the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6. Cell. 2004;118:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berthet C, et al. Combined loss of Cdk2 and Cdk4 results in embryonic lethality and Rb hypophosphorylation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berthet C, Kaldis P. Cell-specific responses to loss of cyclin-dependent kinases. Oncogene. 2007;26:4469–4477. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santamaría D, et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448:811–815. doi: 10.1038/nature06046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satyanarayana A, et al. Genetic substitution of Cdk1 by Cdk2 leads to embryonic lethality and loss of meiotic function of Cdk2. Development. 2008;135:3389–3400. doi: 10.1242/dev.024919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evsikov AV, et al. Cracking the egg: Molecular dynamics and evolutionary aspects of the transition from the fully grown oocyte to embryo. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2713–2727. doi: 10.1101/gad.1471006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fausto N, Campbell JS. The role of hepatocytes and oval cells in liver regeneration and repopulation. Mech Dev. 2003;120:117–130. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postic C, Magnuson MA. DNA excision in liver by an albumin-Cre transgene occurs progressively with age. Genesis. 2000;26:149–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<149::aid-gene16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satyanarayana A, Hilton MB, Kaldis P. p21 Inhibits Cdk1 in the absence of Cdk2 to maintain the G1/S phase DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:65–77. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labib K. How do Cdc7 and cyclin-dependent kinases trigger the initiation of chromosome replication in eukaryotic cells? Genes Dev. 2010;24:1208–1219. doi: 10.1101/gad.1933010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle kinases in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padmakumar VC, Aleem E, Berthet C, Hilton MB, Kaldis P. Cdk2 and Cdk4 activities are dispensable for tumorigenesis caused by the loss of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2582–2593. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00952-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlson CM, Frandsen JL, Kirchhof N, McIvor RS, Largaespada DA. Somatic integration of an oncogene-harboring Sleeping Beauty transposon models liver tumor development in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17059–17064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502974102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vassilev LT, et al. Selective small-molecule inhibitor reveals critical mitotic functions of human CDK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10660–10665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600447103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bienvenu F, et al. Transcriptional role of cyclin D1 in development revealed by a genetic-proteomic screen. Nature. 2010;463:374–378. doi: 10.1038/nature08684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itzhaki JE, Gilbert CS, Porter ACG. Construction by gene targeting in human cells of a “conditional” CDC2 mutant that rereplicates its DNA. Nat Genet. 1997;15:258–265. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.L'Italien L, Tanudji M, Russell L, Schebye XM. Unmasking the redundancy between Cdk1 and Cdk2 at G2 phase in human cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:984–993. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.9.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arias EE, Walter JC. Strength in numbers: Preventing rereplication via multiple mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:497–518. doi: 10.1101/gad.1508907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broek D, Bartlett R, Crawford K, Nurse P. Involvement of p34cdc2 in establishing the dependency of S phase on mitosis. Nature. 1991;349:388–393. doi: 10.1038/349388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ullah Z, Kohn MJ, Yagi R, Vassilev LT, DePamphilis ML. Differentiation of trophoblast stem cells into giant cells is triggered by p57Kip2 inhibition of CDK1 activity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3024–3036. doi: 10.1101/gad.1718108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martín A, et al. Cdk2 is dispensable for cell cycle inhibition and tumor suppression mediated by p27Kip1 and p21Cip1. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee E-C, et al. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics. 2001;73:56–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell JB, et al. Preferential delivery of the Sleeping Beauty transposon system to livers of mice by hydrodynamic injection. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3153–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.