Abstract

Visual cortical surface area varies two- to threefold between human individuals, is highly heritable, and has been correlated with visual acuity and visual perception. However, it is still largely unknown what specific genetic and environmental factors contribute to normal variation in the area of visual cortex. To identify SNPs associated with the proportional surface area of visual cortex, we performed a genome-wide association study followed by replication in two independent cohorts. We identified one SNP (rs6116869) that replicated in both cohorts and had genome-wide significant association (Pcombined = 3.2 × 10−8). Furthermore, a metaanalysis of imputed SNPs in this genomic region identified a more significantly associated SNP (rs238295; P = 6.5 × 10−9) that was in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs6116869. These SNPs are located within 4 kb of the 5′ UTR of GPCPD1, glycerophosphocholine phosphodiesterase GDE1 homolog (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), which in humans, is more highly expressed in occipital cortex compared with the remainder of cortex than 99.9% of genes genome-wide. Based on these findings, we conclude that this common genetic variation contributes to the proportional area of human visual cortex. We suggest that identifying genes that contribute to normal cortical architecture provides a first step to understanding genetic mechanisms that underlie visual perception.

Keywords: allometry, brain morphometry, imaging genetics, V1

Primates, including humans, rely on vision to navigate their environment, find food, and avoid predators. Visual performance varies between primate species partly because of genetic variation, and better vision may have provided an evolutionary fitness advantage. For example, allelic diversity of visual pigments in the eye evolved convergently in apes, Old World monkeys, and howler monkeys (1) and enabled red–green color discrimination, enhancing these primates’ ability to identify sources of food (2).

Visual performance also varies within primate species, such as between human individuals (3), and this performance may be correlated with the number of neurons available to process visual information. Indeed, two studies of healthy human subjects found that increased surface area of primary visual cortex (V1) and thus, more neurons in V1 (4) were associated with increased Vernier acuity (5) and decreased susceptibility to two optical illusions (6). It is striking that visual cortical surface area is associated with optical illusion strength, because this result implies that the number of neurons in V1 can explain human variation in the conscious perception of seemingly physically identical stimuli.

Individuals have highly variable portions of their brains devoted to visual processing, because the surface areas of visual cortical regions (e.g., V1, V2, and V3 in the occipital lobe) are correlated and vary two- to threefold in humans (7, 8). This variation is significantly greater than variation in total cortical area, and therefore, both the absolute area and proportion of the cortical sheet allocated to processing vision varies between individuals. Moreover, a recent human twin study showed strong genetic correlations between the area of V1 and the remainder of occipital cortex but not other cortical lobes (9), suggesting that occipital visual areas share common genetic influences. However, it is still largely unknown what specific genetic and environmental factors contribute to normal variation in the absolute and proportional size of occipital cortex. To address this question, we performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify SNPs associated with the proportional surface area of occipital cortex in two independent human cohorts.

Human twin studies have shown a significant genetic component to cortical volume (10–12) and surface area (>80% heritable) (13–16), and the occipital proportion of cortex is also quite heritable (25–50%) (11, 13). These studies reveal that genes have both global and regional effects on cortical surface area, which also seems to be true in mice. For example, the work by Airey et al. (17) reported that two strains of inbred mice with different genetic backgrounds have different proportions of cortex allocated to primary visual and somatosensory cortex, and these strains can be reliably discriminated based on these regional as well as global measures of cortical surface area.

Furthermore, specific homeobox transcription factors (e.g., EMX2 and PAX6) have been identified that are expressed in gradients across the surface of the mouse brain during neural development and control the anterior–posterior distribution of cortical areas (18, 19). Cortex-specific overexpression of EMX2 in mice resulted in an expansion of occipital areas and a corresponding reduction in sensory and motor areas that led to dysfunctional tactile and motor behaviors (20). Similarly, EMX2 and PAX6 may be expressed in gradients during neural development in human subjects (21), and individuals with protein coding mutations in PAX6 (22, 23) exhibit cortical malformations. In addition, EMX2 mutations have been associated with schizencephaly, a rare cortical developmental disorder (24, 25), although these mutations likely explain a small fraction of this disease burden (26, 27). Finally, mutations in the laminin gene LAMC3 have been associated with cortical malformations solely within the occipital lobe (28), providing additional evidence for genetic control over regional cortical development.

Genetic variants may also mediate more subtle variation in human cortical structure. For example, two candidate gene studies recently identified SNPs in microcephaly genes (29) and MECP2 (30) that explained a small but statistically significant amount of variation in total cortical surface area between human individuals and were replicated in independent study populations.

In this study, we extend the analysis of the datasets used in those studies in two ways. First, we performed an unbiased GWAS rather than selecting candidate genes to identify genetic loci that contribute to normal variation in human cortical structure. Second, we analyzed the scaling of occipital cortical surface area with total cortical area because of the evidence from mice and human twin studies that this scaling relationship may be under independent genetic control from overall brain size.

Results

In a sample of 421 human subjects with Norwegian ancestry from the Thematic Organized Psychoses (TOP) study, we found that occipital cortical surface area is highly correlated with total cortical area (r = 0.85, P = 3.1 × 10−118). The occipital cortex occupied, on average, 12.1% of total cortical surface area regardless of brain size, and the occipital fraction of cortex ranged from 11.1% to 14.8% in all subjects. We hypothesized that this variation was partly because of genetic differences between subjects. Therefore, we tested SNPs genome-wide for their effect on the scaling relationship between occipital and total cortical surface area. Specifically, we tested each SNP in a GWAS for the strength of the interaction between the SNP minor allele account and total cortical surface area in predicting occipital cortical surface area, while controlling for sex, age, and diagnosis. This interaction effect would reflect the degree to which the SNP accentuated the influence of overall cortical surface area on occipital cortical surface area (i.e., modified the scaling relationship between total and occipital cortical surface area).

One SNP (rs6116869; minor allele frequency = 0.36) showed strong interaction association (P = 7.75 × 10−8, β = 0.0285, SE = 0.0052, n = 413) with occipital cortical surface area, although this SNP did not quite reach genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8). A quantile–quantile plot of −log10 (P values) from the GWAS revealed moderate genomic inflation (λGC = 1.25), and this inflation suggested that the original SNP P value may have been artificially low. Thus, we sought a more accurate estimate of the P value in two ways: (i) accounting for genetic relatedness between subjects and (ii) permutation testing. In addition, we tested the SNP for association in two independent replication cohorts and interaction association with surface area across the whole cortex. Finally, we investigated the cortical expression pattern of GPCPD1, a nearby gene, in two human brains.

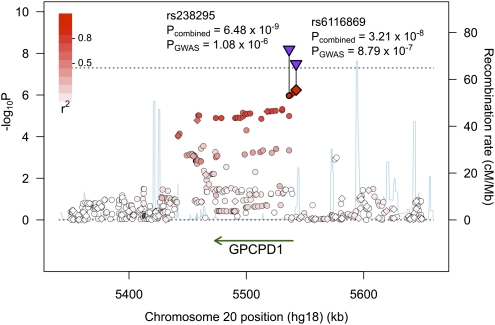

First, despite the fact that subjects were unrelated and self-reported Norwegian ancestry, we hypothesized that subtle population structure or cryptic relatedness could have compromised the statistical independence of subjects. A lack of independence would have decreased SNP variance estimates and associated P values, resulting in genomic inflation. We approximated population structure in our study by using principle components analysis (PCA) to estimate major axes of variation of genome-wide allele frequencies. We repeated the GWAS and controlled for sex, age, and diagnosis as well as population structure along the first four axes from the PCA, which has been shown to help correct for population stratification (31). We found that genomic inflation was slightly reduced (λGC = 1.23), and rs6116969 association was now genome-wide significant (P = 4.95 × 10−8, β = 0.0289, SE = 0.0052). We performed genomic control, and rs6116869 still showed markedly stronger association (PGC = 8.79 × 10−7, β = 0.0289, SEGC = 0.0058) than other SNPs (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1 and S2).

Fig. 1.

Genomic region showing the strongest SNP association with occipital cortical area scaling. Genotyped (♢) and imputed (○) SNPs are colored based on linkage disequilibrium (r2) with rs6116869. Combined P values for rs6116869 and rs238295 (▿) are genome-wide significant (P < 5 × 10−8; dotted line) based on a metaanalysis of the GWAS and two replication studies. rs238288 is not labeled and is located in between these two SNPs. P values are corrected for genomic inflation.

Next, we used permutation tests to estimate the significance of rs6116869 association, and the permuted P value (Pperm = 6 × 10−7) supported the genomic control P value, suggesting that genomic control had effectively corrected for inflation. Thus, for the remainder of the analysis, we report the conservative genomic control SEs and P values.

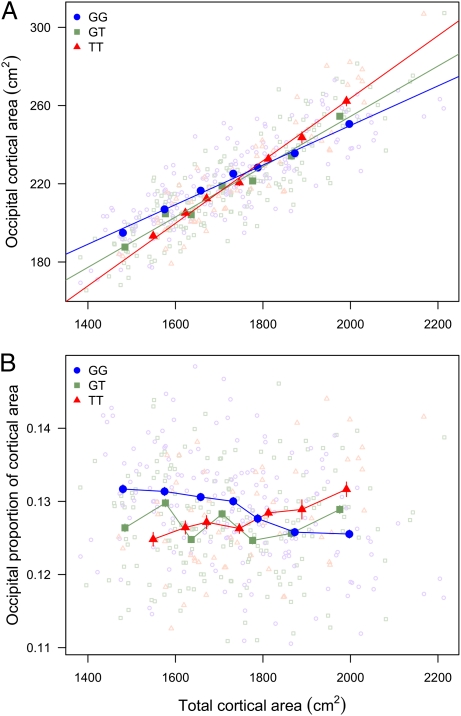

Given the significant interaction effect between rs6116869 and total cortical area, we expected that the slope of the linear regression that related occipital to total cortical surface area would vary based on rs6116869 genotype. Indeed, we found that each copy of the SNP minor allele increased the slope by 28% (Fig. 2A). On average, the occipital cortex of subjects heterozygous for rs6116869 (GT genotype; n = 184) occupied 12.7% of total cortical surface area, and this occipital proportion was independent of total cortical area (Fig. 2B). In contrast, subjects homozygous for the major allele (GG; n = 171) had an occipital proportion that decreased from 13.2% to 12.6%, on average, over the range of total cortical areas observed in our study. Inversely, subjects homozygous for the minor allele (TT; n = 58) had an occipital proportion that increased from 12.5% to 13.2% over this same range. These 0.6% differences in the occipital proportion of cortex based on rs6116869 genotype represented a difference in absolute occipital cortical area of ∼11 cm2, equal to almost one-half the area of V1 (6). Therefore, for example, in the subset of subjects with relatively large total cortical surface area (∼2,000 cm2), subjects with the GG genotype had an occipital cortical area of 251 cm2, whereas subjects with the TT genotype had an occipital cortical area of 262 cm2.

Fig. 2.

Occipital cortical area scaling varies by rs6116869 genotype. (A) The slope of occipital cortical area scaling with total cortical area increases with the number of minor alleles. For each genotype, subjects are grouped into seven bins with an equal number of subjects in each bin (24, 26, and 8 subjects per bin for genotypes GG, GT, and TT, respectively). Binned averages ± SEM (dark) and regression lines fit to individual (light) measures are plotted. (B) Occipital proportion of cortex varies based on total cortical area and genotype. Subjects are binned as in A, and occipital proportions (occipital area divided by total cortical area) are plotted for individuals (light). Binned averages ± SEM (dark) are indicated.

We sought to replicate the rs6116869 association with occipital cortical area in two independent cohorts. First, we used 482 subjects—healthy controls or diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI)—from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) dataset who clustered with European reference populations based on genome-wide genotype data. rs238288 was the closest proxy for rs6116869 that was genotyped in the ADNI sample, and this SNP was highly correlated (r2 = 0.96 in HapMap CEU population with northwestern European ancestry) with and 2.5 kb upstream from rs6116869. We tested rs238288 for a significant interaction with total cortical surface area in predicting occipital cortical surface area with the identical test used in the GWAS (i.e., controlling for sex, age, diagnosis, and population structure). We found modest genomic inflation (λGC = 1.19) (Fig. S3) in the ADNI study that was comparable with the inflation observed in the TOP study. rs238288 was significantly associated before (one-tailed P = 0.0083, β = 0.0123, SE = 0.0051, n = 477) and after (PGC = 0.015) genomic control.

For our second replication cohort, we selected 278 subjects (aged 6–21 y old) from the Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition, and Genetics (PING) study who clustered with European reference populations based on genome-wide genotype data. We excluded PING subjects younger than 6 y, because brain volume increases more than fourfold after birth and then, is mostly stable from age 6 y to adulthood (32). Likewise, cortical surface area decreases less than 10% during adolescence between the ages of 6 and 22 y (33), and therefore, we expected that the effect of genetic variation on the scaling of occipital cortical area would have occurred earlier in development and would be apparent in this younger replication cohort. Indeed, we found that rs238288 (the closest proxy for rs6116869) provided a second replication of the GWAS result (one-tailed P = 0.018, β = 0.0208, SE = 0.0098, n = 278). No genomic inflation was observed in this dataset (λGC = 1.00). The combined P value for rs6116869 from the GWAS and two replication studies was genome-wide significant (Pcombined = 3.21 × 10−8) based on an inverse variance-weighted z score (34).

To refine the association of this genetic locus with occipital cortical area scaling, we imputed SNPs for the TOP, ADNI, and PING samples in a 300-kb window around rs6116869 and performed a metaanalysis of these SNPs. We combined the genomic controlled P values for the imputed SNPs from the three studies (Fig. 1), and we identified the SNP (rs238295) that was most significantly associated (Pcombined = 6.48 × 10−9). rs238295 was highly correlated with and proximal to both rs6116869 (r2 = 0.88, 6 kb upstream) and rs238288 (r2 = 0.84, 3.5 kb upstream).

Given the finite extent of the cortex, we expected that a relative increase in occipital cortical surface area would be associated with a compensatory decrease in surface area in other cortical regions. Therefore, we performed a region of interest analysis in the TOP, ADNI, and PING samples and tested rs238295 for association with 66 regions defined by cortical folding patterns. For each cortical region, we calculated the genomic inflation adjusted P value for the interaction between rs238295 and total cortical surface area, and we combined these P values from the three studies (Table S1). As expected, we found that rs238295 was strongly associated with the surface area of occipital cortical regions, including the bilateral pericalcarine area that is highly correlated with the V1 area (7) as well as lingual and lateral occipital areas. Intriguingly, rs238295 was also significantly associated with left superior and lateral temporal cortical areas in all three studies but in the opposite direction relative to the association with occipital cortical area. Thus, individuals homozygous at rs238295 with a relatively large occipital cortex had a relatively small left temporal cortex and vice versa.

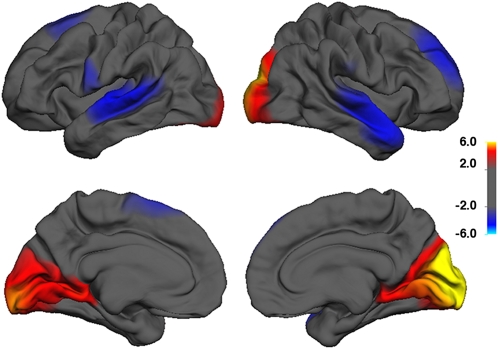

To better visualize the SNP association with different cortical regions in the TOP cohort, we tested the interaction association of rs6116869 with total cortical area at each location across the cortical surface. A cortical map of −log10 (P values) broadly supported the region of interest analysis and also highlighted significant SNP associations with bilateral superior frontal cortical regions in the TOP study (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

P value map (−log10 P value) of rs6116869 association with cortical area scaling at each vertex across the surface of the brain, while controlling for age, sex, and diagnosis. Hot colors indicate increased scaling slope with the number of SNP minor alleles among subjects in the TOP study, and cool colors indicate decreased scaling slope with the number of SNP minor alleles among subjects in the TOP study.

The genotyped SNP that was most significantly associated with the occipital cortical area in the TOP sample (rs6116869) is located ∼3 kb upstream of the protein coding gene GPCPD1, glycerophosphocholine phosphodiesterase GDE1 homolog (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and the most significant imputed SNP in the combined analysis of both TOP and ADNI samples (rs238295) is located 6 kb downstream in the first intron of GPCPD1. These SNPs are at the end of a 100-kb linkage disequilibrium block that spans the full length of the gene, and this block includes a DNA sequence just upstream of the promoter to 30 kb distal to the 3′ UTR.

We explored the cortical expression pattern of GPCPD1 in two adult brains using the Allen Human Brain Atlas (35), and we found that this gene had 1.5-fold greater expression specifically in occipital cortex compared with other cortical regions (Fig. S4). This relatively higher occipital expression was supported by two independent probes used to assess GPCPD1 expression in both brains and more significant (P = 2.1 × 10−19) than 99.9% of genes (all but 11 genes) genome-wide (SI Materials and Methods).

Discussion

We performed a GWAS of occipital cortical area scaling with total cortical surface area in human individuals, and we identified one SNP (rs6116869) that showed strong association (P = 8.8 × 10−7) and replicated in two independent cohorts with a combined P value that was genome-wide significant (Pcombined = 3.2 × 10−8). A metaanalysis of nearby SNPs identified rs238295, in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs6116869, as the most significantly associated SNP (Pcombined = 6.5 × 10−9). Furthermore, rs238295 was associated with the scaling of left temporal cortical area in opposition to the scaling of occipital cortical area. These SNPs are located near the 5′ UTR of GPCPD1, a gene that is more highly expressed in the occipital cortex compared with other cortical regions in the adult human brain than virtually any other gene.

In humans, components of the visual system—retina, optic nerve, and visual thalamus and cortex (V1, V2, and V3)—scale in size together (7, 8). Moreover, mammalian brain size explains more than 95% of the variation in size of individual brain components, including neocortex, presumably because of evolutionarily conserved constraints on neural development (36). However, there is also evidence for mosaic brain evolution, when sets of functionally or anatomically linked brain structures have evolved independently of brain size (37). For example, although visual thalamus and V1 are highly correlated in size in primates, including humans, these visual structures are significantly smaller than would be expected for a nonhuman primate with a brain of human size (38). The mosaic evolution of primary visual cortical surface area among primates suggests that this region was under independent genetic control from the remainder of cortex on the evolutionary lineage leading to modern humans. Genetic variation between primate species that explains differences in the relative sizes of visual cortex may contribute to the two- to threefold variation in surface area of visual cortical regions observed between human individuals.

We found that the proportional area of occipital cortex varied by 33% between individuals (range = 0.11–0.15), and this phenotype showed the same pattern of association with rs238295 as the absolute occipital cortical area. Likewise, the work by Schwarzkopf et al. (6) found that illusion strength was significantly correlated with both the absolute and proportional sizes of primary visual cortex. If a larger fraction of the cortex is allocated to visual processing, then less cortical area and likely, fewer neurons (4, 39) are available to process information in other cortical regions. We found that left superior and lateral temporal cortical surface area was significantly decreased in individuals with relatively large visual cortical area. If this slight reduction in cortical area is associated with decreased information processing capacity, then one could potentially measure subtle changes in auditory processing, including language, which is associated with the left superior temporal gyrus (40). However, more studies are needed to confirm the microstructural basis for MRI measurements of cortical surface area in healthy adults. In addition, studies must distinguish whether absolute or relative cortical surface area is under more direct genetic control and which measure has more functional relevance.

We observed moderate genomic inflation in both the TOP and ADNI studies, although there were no clear outlier measurements of occipital cortical area in either cohort, and residuals from the linear models did not deviate significantly from normality in the TOP (P = 0.63) or ADNI (P = 0.44) studies using a sensitive Shapiro–Wilk test. Although we could attribute only a small part of this inflation to population stratification, subtle population structure or cryptic relatedness may have contributed to the genomic inflation. In any case, the consistency between the P values obtained with permutation testing and genomic control suggested that the genomic control P values that we reported were conservative.

The most highly associated SNPs in this study are located near the 5′ UTR of GPCPD1; a linkage disequilibrium block extends over the full length of the gene, and therefore, it is likely that the functional variant is located within this gene. This genetic proximity suggests a role for GPCPD1 in the scaling of occipital cortex; the next closest protein-coding gene (PROKR2) is over 300 kb away, and previous GWASs have found functional genes near SNPs. For example, a GWAS of height in over 100,000 individuals identified 21 loci containing a known skeletal growth gene, and over one-half of those genes were closest to the associated SNP (41). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the SNPs that we have found are associated with a more distal gene.

The DNA sequence of GPCPD1 is highly conserved from mouse (89% identical) to fruit fly (48%), and the protein includes two conserved domains used in glycogen metabolism in mammals. This gene is widely expressed, including in adult mouse and human brains (35, 42), but its function has only been investigated in mouse skeletal muscle growth (43). Remarkably, in two human brains, only 11 genes genome-wide had significantly higher expression than GPCPD1 in occipital cortex, including MET, SCN1B, and GPR161, which are involved in neurodevelopmental and neurophysiological processes (44–46). A common variant in the promoter of MET has been associated with twofold increased risk for autism spectrum disorder (47), and a mutation in SCN1B has been linked to generalized epilepsy (48). Altered expression of GPCPD1 could possibly contribute to variation in cortical surface area through its role in energy metabolism. Primary visual cortex has two times the density of neurons as other cortical regions (4) and therefore, increased metabolic requirements. If genetic variation in GPCPD1 increased the metabolic efficiency of neurons or glia, then neurons could support larger axonal and dendritic arbors and thus, potentially, a larger visual cortex. Future work will need to establish the role of GPCPD1 in human brain development, aging, and pathology.

In summary, we predict that rs238295 (or a closely linked functional variant) regulates expression of GPCPD1 because of its close proximity to the 5′ UTR of this gene. The timing and location in the brain of this differential expression as well as the mechanism by which this gene influences visual cortical surface area remain to be elucidated. Understanding the role of genes that contribute to normal cortical architecture in humans is an important step to understanding the genetic mechanisms of visual perception and ultimately, cortical pathology in a host of heritable neuropsychiatric disorders.

Materials and Methods

TOP Subjects.

Four hundred and twenty-one subjects from the TOP study were analyzed. These subjects included 181 controls, 94 subjects with schizophrenia spectrum disorder, 97 subjects with bipolar spectrum disorder, and 49 subjects diagnosed with major depressive disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; 48.7% of the subjects were women, and the subjects were aged 35 ± 10 y (range = 18–65 y).

Genotyping.

DNA was genotyped on the Affymetrix 6.0 array as previously reported (52, 53), and 597,198 SNPs passed quality control filters (SNP call rate > 95%, minor allele frequency > 5%, Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium P < 1 × 10−6) and were merged with HapMap 3 reference populations. All subjects self-reported Norwegian ancestry, and PCA of an allele-sharing distance matrix across all subjects did not suggest any non-European ancestry genetic outliers.

Brain imaging.

MRI scans were performed with a 1.5 T Siemens Magnetom Sonata scanner equipped with a standard head coil. Acquisition parameters were optimized for increased gray/white matter image contrast. More details are in SI Materials and Methods and the work by Rimol et al. (51).

ADNI Subjects.

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/); 482 subjects who self-reported as white and non-Hispanic included 180 controls and 302 individuals with MCI (39.2% women; aged 75.3 ± 6.6 y). We included ADNI subjects with MCI but not Alzheimer's disease from the replication sample in an attempt to balance the increased power that resulted from having a larger sample size with the increased noise caused by the pathological changes in cortical surface area that have been associated with these neurological disorders.

Genotyping.

DNA was genotyped with the Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip, and 514,073 SNPs passed quality control filters (SNP call rate > 95%, minor allele frequency > 5%, Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium P < 1 × 10−6) and were merged with 34 European reference populations. PCA of an allele-sharing distance matrix was used to remove three individuals as non-European ancestry genetic outliers.

Imaging.

MRI data were collected on 1.5-T scanners at many study centers across the United States. The Laboratory of Neuro Imaging (LONI) website (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Research/Cores/index.shtml) describes specific protocols. Raw digital imaging and communications in medicine MR images were downloaded from the ADNI data page of the public ADNI site at the LONI website (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Data/index.shtml) published in 2007.

PING Subjects.

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the PING database (http://ping.chd.ucsd.edu/); 278 subjects were included aged 14.2 ± 4.1 y (range = 6–21 y), and 47.8% of subjects were female.

Genotyping.

DNA was genotyped with the Illumina Human660W-Quad BeadChip, and 494,082 SNPs passed quality control filters (sample call rate > 98%, SNP call rate > 95%, minor allele frequency > 5%, Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium P < 1 × 10−6) and were merged with Hapmap European reference populations; 599 individuals were removed as genetic outliers based on PCA of an allele-sharing distance matrix. Additionally, 157 of the remaining subjects were removed, because they shared greater than 10% of alleles identical by descent with another subject.

Imaging.

T1-weighted MRI data were collected on 3-T scanners at nine study centers across the United States. Specific MRI scanner protocols are available at the PING study website (http://ping.chd.ucsd.edu/).

Genotype Imputation.

TOP, ADNI, and PING genotypes were independently merged with the HapMap CEU reference population, which also included genetic variant information from the sequencing by the 1,000 Genomes Project. MACH 1.0 was used to impute genotypes with the default settings, and only SNPs that passed imputation quality control (R > 0.5) were included for additional analysis.

Cortical Area Measurements.

MRI scans were analyzed with software developed at the University of California at San Diego Multi-Modal Imaging Laboratory based on the freely available FreeSurfer software package (http://freesurfer-software.org/). Using cortical surface reconstruction and spherical atlas mapping procedures developed in the works by Dale et al. (52) and Fischl et al. (53), we mapped each individual's surface reconstruction into atlas space based on cortical folding patterns. Cortical folds are good predictors of the locations of functionally distinct regions (53). For example, there is close agreement between anatomical extent of primary visual cortex based on cortical folding patterns, functional MRI, and ex vivo cytoarchitecture (54).

Statistics.

We tested each SNP for association using PLINK (55) to fit an additive linear model with minor allele count, sex, age, diagnosis, total cortical surface area, and a minor allele count by total cortical area interaction term as predictors of occipital cortical surface area. Genomic inflation (λGC) was estimated in the standard way by dividing the median observed χ2 statistic from the GWAS by 0.456, the approximate median of a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom (56).

The permuted P value of the top SNP was calculated by shuffling subject labels (n = 108 permutations), recalculating the SNP interaction P values, and calculating the fraction of permutations that showed a more significant association than the P value derived from the original dataset. P values reported for the replication datasets are one-tailed, because we tested for an SNP effect in the same direction as in the original GWAS. In a metaanalysis of TOP, ADNI, and PING datasets, P values were combined based on inverse variance weighted z scores (34) calculated from the β-coefficients and genomic inflation-adjusted SEs (SEGC). An association plot of combined P values was created using the SNAP plot online tool from the Broad Institute (57).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and the members of the Thematically Organized Psychosis Study group involved in data collection, especially Drs. Jimmy Jensen, Per Nakstad, and Andres Server. We also thank Eivind Bakken, Thomas Doug Bjella, Alan Koyama, Robin G. Jennings, Chris J. Pung, and Dr. Christine Fennema-Notestine. This work was supported by the Oslo University Hospital–Ullevål, South-Eastern Norway Health Authority Grant 2004-123, Research Council of Norway Grants 167153/V50 and 163070/V50, and Eli Lilly Inc. for parts of the genotyping costs of the TOP sample. Data collection and sharing for a portion of this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; National Institute of Health Grant U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and it is also funded through generous contributions from Pfizer Inc., Wyeth Research, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Co. Inc., AstraZeneca AB, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Alzheimer's Association, Eisai Global Clinical Development, Elan Corporation plc, Forest Laboratories, and the Institute for the Study of Aging, with participation from the US Food and Drug Administration. Industry partnerships are coordinated through the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California at San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory of Neuroimaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AG031224, R01AG22381, U54NS056883, P50NS22343, P50MH081755, 5UL1RR025774, U01DA024417, R01AG030474, R01MH080134, R01HL089655, U54CA143906, R01AG035020, R01DA030976, U19AG023122-01, R01MH078151-01A1, N01MH22005, and RC2DA029475. This work was also supported by the Price Foundation and Scripps Genomic Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: I.M. has received a speaker's honorarium from Janssen and AstraZeneca. I.A. has served as an unpaid consultant for Eli Lilly. O.A.A. has received a speaker's honorarium from AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and GlaxoSmithKline. A.M.D. is a founder and holds equity in CorTechs Labs and also serves on its Scientific Advisory Board. Eli Lilly supported parts of the genotyping costs for the Thematic Organized Psychoses Study sample. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of California at San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

2A complete list of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition, and Genetics Study authors can be found in the SI Appendix.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1105829109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shyue SK, et al. Adaptive evolution of color vision genes in higher primates. Science. 1995;269:1265–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.7652574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dominy NJ, Lucas PW. Ecological importance of trichromatic vision to primates. Nature. 2001;410:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35066567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpern SD, Andrews TJ, Purves D. Interindividual variation in human visual performance. J Cogn Neurosci. 1999;11:521–534. doi: 10.1162/089892999563580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockel AJ, Hiorns RW, Powell TP. The basic uniformity in structure of the neocortex. Brain. 1980;103:221–244. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan RO, Boynton GM. Cortical magnification within human primary visual cortex correlates with acuity thresholds. Neuron. 2003;38:659–671. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarzkopf DS, Song C, Rees G. The surface area of human V1 predicts the subjective experience of object size. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:28–30. doi: 10.1038/nn.2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews TJ, Halpern SD, Purves D. Correlated size variations in human visual cortex, lateral geniculate nucleus, and optic tract. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2859–2868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02859.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougherty RF, et al. Visual field representations and locations of visual areas V1/2/3 in human visual cortex. J Vis. 2003;3:586–598. doi: 10.1167/3.10.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CH, et al. Genetic influences on cortical regionalization in the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baaré WF, et al. Quantitative genetic modeling of variation in human brain morphology. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:816–824. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.9.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitt JE, et al. A twin study of intracerebral volumetric relationships. Behav Genet. 2010;40:114–124. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9332-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace GL, et al. A pediatric twin study of brain morphometry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:987–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyler LT, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to regional cortical surface area in humans: A magnetic resonance imaging twin study. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2313–2321. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panizzon MS, et al. Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2728–2735. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tramo MJ, et al. Brain size, head size, and intelligence quotient in monozygotic twins. Neurology. 1998;50:1246–1252. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White T, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P. Brain volumes and surface morphology in monozygotic twins. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:486–493. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.5.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Airey DC, Robbins AI, Enzinger KM, Wu F, Collins CE. Variation in the cortical area map of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice predicts strain identity. BMC Neurosci. 2005 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Leary DD, Chou SJ, Sahara S. Area patterning of the mammalian cortex. Neuron. 2007;56:252–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop KM, Goudreau G, O'Leary DD. Regulation of area identity in the mammalian neocortex by Emx2 and Pax6. Science. 2000;288:344–349. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leingärtner A, et al. Cortical area size dictates performance at modality-specific behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4153–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611723104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayatti N, et al. Progressive loss of PAX6, TBR2, NEUROD and TBR1 mRNA gradients correlates with translocation of EMX2 to the cortical plate during human cortical development. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1449–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sisodiya SM, et al. PAX6 haploinsufficiency causes cerebral malformation and olfactory dysfunction in humans. Nat Genet. 2001;28:214–216. doi: 10.1038/90042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell TN, et al. Polymicrogyria and absence of pineal gland due to PAX6 mutation. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:658–663. doi: 10.1002/ana.10576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunelli S, et al. Germline mutations in the homeobox gene EMX2 in patients with severe schizencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;12:94–96. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faiella A, et al. A number of schizencephaly patients including 2 brothers are heterozygous for germline mutations in the homeobox gene EMX2. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5:186–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merello E, et al. No major role for the EMX2 gene in schizencephaly. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1142–1150. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tietjen I, et al. Comprehensive EMX2 genotyping of a large schizencephaly case series. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1313–1316. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barak T, et al. Recessive LAMC3 mutations cause malformations of occipital cortical development. Nat Genet. 2011;43:590–594. doi: 10.1038/ng.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rimol LM, et al. Sex-dependent association of common variants of microcephaly genes with brain structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:384–388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908454107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joyner AH, et al. A common MECP2 haplotype associates with reduced cortical surface area in humans in two independent populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15483–15488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courchesne E, et al. Normal brain development and aging: Quantitative analysis at in vivo MR imaging in healthy volunteers. Radiology. 2000;216:672–682. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au37672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raznahan A, et al. How does your cortex grow? J Neurosci. 2011;31:7174–7177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bakker PI, et al. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R122–R128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen Human Brain Atlas 2011. Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle, WA. Available at http://human.brain-map.org. Accessed March 25, 2011.

- 36.Finlay BL, Darlington RB. Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science. 1995;268:1578–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.7777856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barton RA, Harvey PH. Mosaic evolution of brain structure in mammals. Nature. 2000;405:1055–1058. doi: 10.1038/35016580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Sousa AA, et al. Hominoid visual brain structure volumes and the position of the lunate sulcus. J Hum Evol. 2010;58:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rakic P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science. 1988;241:170–176. doi: 10.1126/science.3291116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang EF, et al. Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1428–1432. doi: 10.1038/nn.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lango Allen H, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lein ES, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okazaki Y, et al. A novel glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase, GDE5, controls skeletal muscle development via a non-enzymatic mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27652–27663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen C, et al. Mice lacking sodium channel beta1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4030–4042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4139-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matteson PG, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr161, encodes the vacuolated lens locus and controls neurulation and lens development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2088–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705657105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Judson MC, Amaral DG, Levitt P. Conserved subcortical and divergent cortical expression of proteins encoded by orthologs of the autism risk gene MET. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1613–1626. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell DB, et al. A genetic variant that disrupts MET transcription is associated with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16834–16839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605296103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wallace RH, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Genet. 1998;19:366–370. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Athanasiu L, et al. Gene variants associated with schizophrenia in a Norwegian genome-wide study are replicated in a large European cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:748–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Djurovic S, et al. A genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in Norwegian individuals, followed by replication in Icelandic sample. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rimol LM, et al. Cortical thickness and subcortical volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, Dale AM. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:272–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<272::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hinds O, et al. Locating the functional and anatomical boundaries of human primary visual cortex. Neuroimage. 2009;46:915–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devlin B, Roeder K, Wasserman L. Genomic control, a new approach to genetic-based association studies. Theor Popul Biol. 2001;60:155–166. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2001.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson AD, et al. SNAP: A web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.