Abstract

Background.

Most studies of leukocyte telomere length (LTL) focus on diagnosed disease in one system. A more encompassing depiction of health is disease burden, defined here as the sum of noninvasively measured markers of structure or function in different organ systems. We determined if (a) shorter LTL is associated with greater age-related disease burden and (b) shorter LTL is less strongly associated with disease in individual systems or diagnosed chronic conditions (cardiovascular disease, stroke, pulmonary disease, diabetes, kidney disease, arthritis, or depression).

Methods.

LTL was measured by Southern blots of terminal restriction fragment length. Age-related disease was measured noninvasively and included carotid intima–media thickness, lung vital capacity, white matter grade, cystatin-C, and fasting glucose; each graded 0 (best tertile), 1 (middle tertile), or 2 (worst tertile) and summed (0 to 10) to estimate disease burden. Of 419 participants randomly selected for LTL measurement, 236 had disease burden assessed (mean [SD] age 74.2 [4.9] years, 42.4% male, 86.8% white, and 13.2% black).

Results.

Mean (SD) LTL was 6,312 (615) bp, and disease score was 4.7 (2.1) points. An SD higher disease score (β [SE] = −132 [47] bp, p < .01), age (β [SE] = −107 [46], p = .02) or carotid thickness (β [SE] = −95 [40] bp, p = .02) was associated with shorter LTL, but diagnosed conditions or number of conditions were not associated with LTL. Disease score attenuated the effect of age on LTL by 35%.

Conclusion.

LTL was associated with a characterization of age-related disease burden across multiple physiologic systems, which was comparable to, but independent of, its association with age.

Keywords: Leukocyte telomere length, Disease burden, Noninvasive measurements, Aging

Although biologic age may be impossible to define completely, it will be better understood by uncovering biomarkers of aging. In the future, these biomarkers might guide preventive or therapeutic interventions before clinical onset of age-related disease. Leukocyte telomere length (LTL) might be such a biomarker because it ostensibly records the accruing burden of inflammation and oxidative stress, processes thought to contribute to aging and disease pathogenesis (1–3). LTL undergoes progressive shortening with age, and in the general population, it is comparatively short in individuals with atherosclerosis or those at risk for this aging-related disease (4). The evidence for LTL as an overall biomarker of aging remains unclear, though, due to variation in the strength of detected associations, differences in results based on measurement method and selected outcome, lack of data coupling longitudinal measurements of LTL and aging phenotypes, and theoretical considerations of whether a single marker can accurately and strongly record aging across the life span (5–7).

Most studies of LTL concern only clinically diagnosed disease, but in cohort studies of older individuals without clinically diagnosed disease, the prevalence and severity range of subclinical disease can be substantial when assessed using several noninvasive methods (8–11). Furthermore, undiagnosed disease can powerfully predict incident adverse events independent of diagnosed disease (8–14). Defining disease in categorical (yes/no) terms is imprecise, whereas using quantitative biomarkers might provide a more realistic picture of age-related disease load. Therefore, previous studies relying on disease categorization may have missed associations between LTL and age-related disease.

Most studies exploring the links between LTL and age-related disease have focused on a single organ or biologic system rather than “disease burden” across systems. Here, we define “disease burden” as the sum of noninvasively measured markers of age-related dysfunctions in structure or physiology of different organ systems. This distinction is relevant because LTL apparently records systemic burden of inflammation and oxidative stress. Thus, a study of LTL and disease burden is warranted to clarify the validity of LTL as a biomarker of aging or age-related disease.

Recently, Newman and colleagues (15) developed a physiologic index of comorbidity (index), a 10-point scale that tabulates the severity of age-related chronic disease using noninvasive tests of the vasculature, lungs, kidneys, brain, and glucose metabolism. This estimates an individual’s disease burden regardless of whether disease is clinically recognized. Given its more continuous range, it demonstrated the spectrum of chronic disease in a general population of community-dwelling older adults. The index explained 40% of the age effect on mortality risk and illustrated that high disease burden, even when clinically unrecognized, was significantly associated with mobility limitation and failure to complete activities of daily living. The index appears to be a valid measure of disease burden and stratifies individuals into a wide range of risk.

Using data on LTL and age-related disease burden from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), we conducted this analysis to test two hypotheses: (a) Shorter LTL is associated with greater age-related disease burden and (b) shorter LTL is less strongly associated with disease in individual systems or diagnosed chronic conditions (cardiovascular disease, stroke, pulmonary disease, diabetes, kidney disease, arthritis, or depression).

METHODS

Population

The CHS is an ongoing community-based study of cardiovascular risk in 5,888 men and women older than the age of 65 years from four regions of the United States (16). The cohort was enrolled in 1989–1990 (N = 5,201) and was supplemented with added minority recruitment in 1992–1993 (N = 687). Participants and eligible household members were identified from a random sample of Medicare enrollees at each field center. Participants were aged 65 years or older, and to be eligible, they could not have cancer under active treatment, could not be wheelchair or bed bound in the home, and did not plan to move out of the area within 3 years. Using blood samples from the 1992–1993 examination, 419 CHS participants were originally randomly selected for LTL measurement. Of these, 236 had index scores available and form the study population for this analysis (mean [SD] age 74.2 [4.9] years, range 65–91 years, interquartile range 71–77 years, 42.4% male, 86.8% white, and 13.2% black). Participants without index scores available were less educated (61.2% with less than a college education vs 49.6% with less than a college education, p = .02), less likely to be white (76.0% vs 86.4% vs p < .01), and had high fibrinogen (334 vs 316 mg/dL, p = .01). They had similar LTL (6,312 vs 6,367 bp, p = 0.36), age (74.2 vs 74.2 years, p = .97), gender (39.3% men vs 42.4% men, p = .53), smoking history (53.6% ever smoked vs 51.3% ever smoked, p = .64), body mass index (BMI; 27.8 vs 26.9 kg/m2, p = .06), C-reactive protein (CRP; 3.02 vs 2.59 mg/L, p = .12), and total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides (all p > .3), indicating that selection bias was likely minimal. The CHS is approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Physiologic Index of Comorbidity

The instruments and methods used to construct the index have been described previously (15). Briefly, the clinical examination conducted in 1992–1993 included cardiovascular and pulmonary function tests, blood tests for glucose tolerance and kidney function, and a brain magnetic resonance imaging. The choice of tests to include in the index was based on previous reports that each is individually an important predictor of mortality and that each represents a major common age-related chronic disease (16,17). Carotid ultrasound was obtained in the left and right internal and common carotid arteries to assess near and far wall thicknesses and Doppler flow. The mean of the maximum wall thickness of the internal carotid artery was used to represent the extent of vascular disease (18). Spirometry was conducted according to the standards of the American Thoracic Society (16). Fasting glucose was assessed as described previously (19). Cystatin-C, a serum marker of glomerular filtration rate, was assessed using a BNII nephelometer that used a particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assay (20). Brain magnetic resonance imaging was obtained according to a standard scanning protocol, and data were interpreted at a central magnetic resonance imaging Reading Center by a neurologist trained in a standardized protocol (21). The white matter grade score was used to indicate small-vessel vascular disease in the brain (17).

To construct the index, each of the five measures was divided into three groups with the best values classified as 0 and the worst as 2 (15). Although the choice of cutpoints was arbitrary, the best score of ‘‘0’’ was generally found to represent a healthy normal value, and values of ‘‘2’’ were in the range of individuals with diagnosed chronic disease. Individual scores were summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 10. For the carotid wall thickness, tertile cut points were scored as 0: 0.60–1.06 mm, 1: 1.06–1.53 mm, and 2: 1.53–3.94 mm. Because there was little overlap between men and women for forced vital capacity, tertile cut points for forced vital capacity were sex specific (women: 0: 2.6–3.8 L, 1: 2.2–2.6 L, and 2: 0.6–2.2 L; men: 0: 3.9–6.5 L, 1: 3.2–3.9 L, and 2: 0.3–3.2 L). Tertile cutpoints for cystatin-C were scored as 0: 0.6–1.0 mg/L, 1: 1.0–1.1 mg/L, and 2: 1.1–3.5 mg/L. For white matter grade, tertile cutpoints were scored as 0: 0–1 units, 1: 2 units, and 2: 3–9 units on the 0–9 ordinal scale. Fasting glucose was the only measure not classified by tertile. Although results were similar, for clinical interpretation, this presentation uses cutpoints classified according to clinical cutpoints defined by the American Diabetes Association (0: <100 mg/dL, 1: 100–126 mg/dL, and 2: >126 mg/dL) (22).

Terminal Restriction Fragment Length

CHS participants eligible for LTL measurement were randomly selected from those who completed the 1992–1993 clinic examination, consented to DNA preparation and use, had at least 12 μg of DNA available, and had stored leukocytes for additional DNA preparation. The integrity of the DNA was assessed through electrophoresis on 1.0% agarose gels, and LTL was measured as the mean length of the terminal restriction fragments by the Southern blot method previously described (23,24). Each sample was analyzed twice for LTL measurement (on different gels on different occasions), and the mean was used for statistical analyses. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the duplicates of this sample was .97, with an average inter-assay coefficient of variation of 1.5%. The laboratory conducting the terminal restriction fragment length measurements was blinded to all characteristics of participants.

Demographic, Behavioral Health, and Clinical Disease Variables

Covariates were selected for their documented or proposed association with age-related diseases included in the index or LTL. Age, sex, race (black, white, or other), and education were ascertained by self-report. Smoking was assessed by a standardized interview (25). Blood pressure, height, and weight were assessed by standardized protocols. BMI was calculated as kilograms per meter squared. CRP was assessed with a high-sensitivity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (26). The inter-assay coefficient of variation was 5.50%. Plasma fibrinogen was measured using a semiautomated modified clot-rate method. The mean monthly coefficient of variation for the fibrinogen assay was 3.09%. For consistency, we tabulated clinically diagnosed chronic conditions using the same methods as in the original report of the index (15). Pulmonary disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and arthritis were assessed by self-report of physician diagnosis to depict what would be diagnosed disease. Depression was defined on the basis of a score greater than 10 on a modified 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale score (27,28). Reports of cardiovascular disease and stroke were confirmed by review of medications and medical records (16). Using this information, a count of diagnosed chronic conditions was constructed for each person with a maximum of seven for these conditions: cardiovascular disease, stroke, pulmonary disease, diabetes, kidney disease, arthritis, and depression (15).

Statistical Analysis

To depict population characteristics and identify potential confounders, we evaluated the association between covariates and the index or LTL using a test for trend, χ2 test or Fisher exact test, where appropriate. A lowess smoothed curve was used to inform modeling of the association of the index to LTL. It implied a linear form, which was supported by a goodness-of-fit test after model building. We hypothesize that LTL is a predictor of disease outcomes but set up this cross-sectional analysis with LTL as the dependent variable in order to express association in terms of base pairs of LTL. This is consistent with most other reports in the literature. Furthermore, it allowed us to compare age and disease directly in their associations with LTL. Subsequently, we built a series of general linear models using the index as the predictor and LTL as the outcome adjusting for covariates as follows: unadjusted model, model 1 (adjusted for age, gender, and race), model 2 (model 1 plus education, BMI, and current smoking status), model 3 (model 2 plus fibrinogen and natural logarithm of CRP), and model 4 (model 3 plus the number of diagnosed chronic conditions). In the full model, we tested for interactions between the index and each covariate. Variance inflations factors were calculated for model covariates and confirmed that collinearity was minimal (all VIFs < 2). The percent variance in LTL independently explained by the index or age, after adjustment for covariates, was determined using the part correlation (29).

To test if LTL was associated with disease in individual physiologic systems, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between LTL and each index component. We also built general linear models with each component predicting LTL adjusting for age, gender, and race. To see if mean LTL was different by presence or absence of diagnosed chronic conditions, we used the two-sample t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test. In model 4 (above), we also replaced the count of diagnosed chronic conditions with the conditions themselves to test if they were associated with LTL independent of potential confounders. For all analyses, we used a two-sided alpha of .05 to determine significance and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Mean (SD) LTL was 6,312 (615) bp, and index score was 4.7 (2.1) points. Higher disease burden was associated with being older, higher CRP and fibrinogen, smoking, coronary heart disease, and diabetes (Table 1). LTL was associated with age (Pearson r = −.269, p < .001) and smoking (current smoker 6,260 bp vs past smoker 6,196 bp vs never smoker 6,421 bp, p = .03). Though LTL was not associated with gender (women 6,374 bp vs men 6,226 bp, p = .07) and race (whites 6,299 bp vs blacks 6,392 bp, p = .43), trends were as expected. LTL was not associated with BMI, education, CRP, fibrinogen, or a count of diagnosed chronic conditions (all p > .1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants by Physiologic Index Score Group: The Cardiovascular Health Study, 1992–1993 Examination

| Physiologic Index Score Group | |||||

| Characteristics | 0–2 (N = 40) | 3–4 (N = 77) | 5–6 (N = 67) | 7–10 (N = 52) | p* |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 71.1 (2.8) | 72.9 (3.6) | 75.6 (5.6) | 76.8 (4.8) | <.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 10 (25.0) | 35 (45.5) | 32 (47.8) | 23 (44.2) | .11 |

| Black race, n (%) | 8 (20.0) | 8 (10.4) | 7 (10.5) | 9 (17.3) | .35 |

| Behavioral risk factors | |||||

| Education less than college, N (%) | 18 (45.0) | 32 (41.6) | 39 (58.2) | 28 (53.9) | .20 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26.8 (3.4) | 26.6 (4.0) | 27.0 (4.5) | 27.4 (3.8) | .19 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current, n (%) | 4 (10.0) | 3 (3.9) | 10 (14.9) | 8 (15.4) | .03 |

| Past, n (%) | 15 (37.5) | 26 (33.8) | 33 (49.3) | 23 (44.2) | |

| Never, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 48 (62.3) | 24 (35.8) | 21 (40.4) | |

| Diagnosed chronic health conditions | |||||

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 12 (15.6) | 18 (26.9) | 14 (26.9) | .04 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (2.6) | 4 (6.0) | 3 (5.8) | .69 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (5.2) | 16 (23.9) | 14 (26.9) | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease, n (%) | 12 (30.0) | 20 (26.0) | 24 (35.8) | 14 (26.9) | .59 |

| Kidney disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (3.0) | 1 (1.9) | .83 |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 18 (45.0) | 41 (53.3) | 30 (44.8) | 19 (36.5) | .31 |

| Depression (CES-D >10), n (%) | 2 (5.0) | 8 (10.4) | 7 (10.5) | 7 (13.5) | .62 |

| No. of conditions, 0–7, mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.1) | <.01 |

| Inflammation and coagulation markers | |||||

| CRP, mg/L, mean (SD) | 2.73 (2.75) | 4.19 (8.64) | 4.17 (4.07) | 6.25 (9.81) | <.001 |

| ln(CRP), mean (SD) | 0.671 (0.788) | 0.835 (0.945) | 1.03 (0.922) | 1.23 (1.02) | <.001 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 300 (54.8) | 309 (61.8) | 319 (55.6) | 335 (59.8) | <.001 |

Notes: CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale; CRP = C-reactive protein.

p value from test of trend, chi-square test, or Fisher exact test.

The index was significantly inversely correlated with LTL (Pearson r = −.296, p < .001). In an unadjusted model, each SD higher index score was associated with a 183-bp shorter LTL (p < .001; Table 2). For comparison, when modeled by itself, an SD higher age was associated with a 165-bp shorter LTL (p < .001). In a model with only the index and age, the two factors attenuated the association of each other to LTL (index β [SE] = −134 [42] bp per SD, p < .01; age β [SE] = −102 [44] bp per SD, p = .02), but each remained significantly associated with LTL.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Models of the Association of Leukocyte Telomere Length to Physiologic Index Score

| Age itself* | Index itself* | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | Model 4‖ | |||||||

| Covariate | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p |

| Index score, 1 SD | −183(38) | <0.001 | −132 (42) | <0.001 | −130 (45) | <0.01 | −124 (46) | <0.01 | −132 (47) | <0.01 | ||

| Age, 1 SD | −165(39) | <0.001 | −102 (44) | 0.02 | −106 (45) | 0.02 | −111 (46) | 0.02 | −107 (46) | 0.02 | ||

| Male gender | −123 (77) | 0.11 | −118 (78) | 0.13 | −128 (80) | 0.11 | −122 (80) | 0.13 | ||||

| Black race | 73 (111) | 0.51 | 92 (115) | 0.42 | 88 (115) | 0.45 | 84 (115) | 0.47 | ||||

| Behavioral risk factors | ||||||||||||

| Education less than college | 0 (78) | 0.99 | −4 (79) | 0.96 | −12 (81) | 0.88 | ||||||

| Body mass index, 1 SD | −9 (40) | 0.82 | −9 (42) | 0.83 | −15 (43) | 0.73 | ||||||

| Current smoking status | −36 (129) | 0.78 | −46 (131) | 0.72 | −45 (131) | 0.73 | ||||||

| Inflammation and coagulation markers | ||||||||||||

| ln(CRP), 1 SD | −61 (44) | 0.17 | −65 (44) | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Fibrinogen, 1 SD | 41 (46) | 0.37 | 44 (46) | 0.34 | ||||||||

| No. of diagnosed chronic health conditions, 1 point | 33 (42) | 0.43 | ||||||||||

Notes: CRP = C-reactive protein.

Unadjusted. The difference in base pairs in mean leukocyte telomere length given a 1 SD higher continuous covariate or the presence of a categorical covariate.

Adjusted for age, gender, and race.

Additionally adjusted for education, body mass index, and current smoking status.

Additionally adjusted for ln(CRP) and fibrinogen.

Additionally adjusted for number of diagnosed chronic health conditions.

In the fully adjusted model, an SD higher index score was associated with a 132-bp shorter LTL (p < .01). An SD higher age was associated with a 107-bp shorter LTL (p = .02), illustrating that the association of disease burden was independent of, and similar to, the association of age with LTL. The association of an SD in the index score (2.1 points) was equivalent to the association of 5.9 years of age with LTL. When the index was removed from the full model, the effect of age increased from −107 bp per SD to −165 bp per SD (p < .001), indicating that the index attenuated the effect of age by 35%. There was no interaction with the index, and other covariates were not significantly associated with LTL. In the full model, disease burden independently accounted for 3.1% of the variance in LTL, whereas age independently accounted for 2.1% of the variance in LTL.

Regarding continuous components of the index, higher carotid artery thickness, white matter grade, and serum cystatin-C but not forced vital capacity or serum fasting glucose were significantly correlated with shorter LTL (Table 3). In linear models adjusted for age, gender, and race, only carotid thickness was independently associated with LTL, though white matter grade was borderline associated with LTL (Table 3). After further adjustment for BMI, education, smoking, CRP, fibrinogen, and a count of diagnosed chronic conditions, the effect of an SD higher carotid thickness (β [SE] = −95 [40] bp, p = .02) was about three fourth that of the effect of the index. Including all index components in the same model resulted in similar findings, illustrating that the components were operating relatively independently.

Table 3.

Association of Leukocyte Telomere Length to Disease in Components of the Physiologic Index

| Component of the Physiologic Index* | Mean (SD) Leukocyte Telomere Length (bp) | Pearson r† | p† | Linear β (SE)‡ | p‡ |

| Carotid artery thickness | |||||

| 0 (0.60–1.06 mm) | 6,540 (602) | ||||

| 1 (1.06–1.53 mm) | 6,252 (591) | −.214 | .001 | −100 (39) | .01 |

| 2 (1.53–3.94 mm) | 6,168 (600) | ||||

| White matter grade | |||||

| 0 (0–1 units) | 6,422 (607) | ||||

| 1 (2 units) | 6,386 (644) | −.180 | <.01 | −71 (41) | .09 |

| 2 (3–9 units) | 6,121 (554) | ||||

| Serum fasting glucose | |||||

| 0 (<100 mg/dL) | 6,365 (618) | ||||

| 1 (100–126 mg/dL) | 6,256 (632) | −.063 | .33 | −49 (39) | .21 |

| 2 (>126 mg/dL) | 6,239 (560) | ||||

| Serum Cystatin-C | |||||

| 0 (0.6–1.0 mg/L) | 6,413 (651) | ||||

| 1 (1.0–1.1 mg/L) | 6,344 (578) | −.084 | .20 | 1 (41) | .98 |

| 2 (1.1–3.5 mg/L) | 6,187 (606) | ||||

| Forced vital capacity | |||||

| 0 (W: 2.6–3.8 L, M: 3.9–6.5 L) | 6,369 (592) | ||||

| 1 (W: 2.2–2.6 L, M: 3.2–3.9L) | 6,352 (635) | −.019 | .77 | 11 (52) | .83 |

| 2 (W: 0.6–2.2 L, M: 0.3–3.2 L) | 6,218 (612) | ||||

Notes: Zero represents a normal physiologic value. Two represents higher disease burden.

Correlation of leukocyte telomere length with disease in each component of the index, modeled as a continuous variable.

The difference in base pairs in mean leukocyte telomere length given a standard deviation higher component of the physiologic index, adjusted for age, gender, and race. Units are carotid artery thickness, 0.49 mm; white matter grade, 1.4 units; serum fasting glucose, 28.9 mg/dL; serum cystatin-C, 0.30 mg/L; and forced vital capacity, 0.89 L.

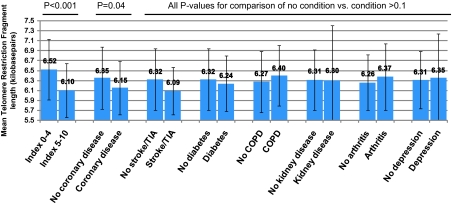

Regarding diagnosed chronic conditions, LTL was shorter with coronary heart disease (6,152 vs 6,351 bp, p = .04) but not with other conditions (Figure 1). When age was adjusted for, coronary heart disease was no longer associated with LTL (6,163 vs 6,348 bp, p = .06), and the association was attenuated more with additional adjustment for race, smoking, BMI, education, and CRP (6,196 vs 6,343 bp, p = .14). For comparison, when the index was dichotomized, those in the unhealthier half of the index (5–10 points) had markedly shorter LTL than those in the healthier half of the index (0–4 points; 6,102 vs 6,525 bp, p < .001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) leukocyte telomere length by index score category or presence of diagnosed chronic conditions.

Because carotid thickness seemingly accounted for a substantial portion of the association of the index to LTL, we conducted a post-hoc analysis removing carotid thickness from the index to determine if nonvascular disease burden remained independently associated with LTL. In an unadjusted model, an SD in the index without carotid thickness was associated with LTL (β [SE] = −147 [39] bp, p < .001). Adjustment for age, gender, and race attenuated the association (β [SE] = −95 [43] bp, p = .03). Additional adjustment attenuated the association to borderline nonsignificance (β [SE] = −89 [47] bp, p = .06).

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that shorter LTL is associated with greater age-related disease burden and that shorter LTL is less strongly associated with disease in individual systems or diagnosed chronic conditions. Our cross-sectional analysis shows that LTL was indeed strongly and independently associated with disease burden, a characterization of age-related chronic disease in five major physiologic systems independent of clinical diagnosis. In contrast, LTL was less strongly associated with disease in individual systems, except possibly carotid thickness, and was not associated with diagnosed chronic conditions or a count of diagnosed chronic conditions. Based on this data, we advocate that in older adults, LTL may be associated most with processes that contribute to atherosclerosis and/or hypertension and perhaps additional processes that contribute to structural and physiological changes in other organs, such as accumulation of white matter hyperintensities. It is possible that LTL might indicate widespread incremental changes in structure or function in older adults but most powerfully vascular changes.

These results provide insight on measuring the biologic age of a human. LTL is a proposed indicator of aging, so it is standard to correlate LTL with age. We found that an SD in the physiologic index or chronologic age had a similar independent association with LTL. Age attenuated the effect of the index substantially, but the index in turn accounted for 35% of the age effect on LTL. Although one could claim that the association of the index to LTL is partially explained by age, another perspective is that the association of age to LTL is partially explained by the index. These findings lend credence to the use of noninvasive tests of physiologic structure and function to monitor the integrity of an aging adult. It demonstrates that novel biomarkers, such as LTL, hold great promise for unraveling the underlying aging process.

The significant association between LTL and carotid thickness and weaker associations with other systems may illustrate how organs age differently. Carotid thickness reflects seemingly normal medial thickening with age, vascular remodeling in response to hypertension, and atherosclerosis. The literature describes a robust association between LTL and atherosclerosis (23,30-40). In our analysis, carotid thickness did not account for the complete association between LTL and disease burden. White matter grade may illustrate normal brain aging in addition to hypertension and dementia. Using techniques other than magnetic resonance imaging, some reports suggest that LTL may register cognitive aging or dementia. Notably, in 382 women not diagnosed with dementia or cognitive impairment, shorter LTL was independently associated with worse memory and learning (41). This is supported by data from the Nurses’ Health Study (42) and a hospital-based case–control study (43) but not by a cohort of 449 inpatients in which there was no difference in LTL between patients who were cognitively normal, had mild cognitive impairment, or were demented (44). A report from the Health Aging and Body Composition study, where LTL was examined in association with cognitive function in 2,734 nondemented community-dwelling older adults, provides inconclusive results (45). The data presented here may support the idea of organ-specific aging or disease progression rather than simultaneous decline in organ function. It should be noted, though, that different magnitudes of associations between LTL and select tissues may depend on the specificity of markers for those tissues and also differences in power to detect significant associations using dichotomized or classified outcomes versus continuous outcomes with a wider variance. Future studies must carefully compare results in light of measurement methods, which focus on different points along the aging disease continuum.

Our data must also be interpreted in light of our construct for disease burden. We wanted to count major physiologic systems only once and not give extra weight to cardiovascular disease. These conditions were selected because they are the most common chronic conditions in older adults. In our previous work, we showed clearly that these five systems characterize mortality risk quite comprehensively (15), Furthermore, we showed that a count of diagnosed conditions, including those not ascertained by the five-component physiologic index, can identify high-risk individuals but not the lowest risk individuals as is achieved by the five-point physiologic index. The lack of association of LTL with individual diagnosed conditions is likely not only due to the lower power of using dichotomous variables but also due to the fact that there is a wide range of measurable disease in those not yet diagnosed. The partial overlap could potentially place the physiologic index at a disadvantage in prediction compared with a comorbidity count, which is addressed more fully in the prior publication (15). Other approaches for measuring disease burden can be argued, and more work is needed to determine the optimal balance between information gained and maintaining a biologically logical construct.

This study is strengthened by the use of Southern blot, the gold standard, to measure LTL. Although LTL was measured in a random sample of the CHS cohort, which should minimize selection bias, we acknowledge the potential for selection bias, which may have resulted from using a subset of this random sample. Nonetheless, the original report from the CHS random LTL sample also found no association with BMI, fasting glucose, and hypertension and similar trends with carotid thickness, gender, CRP, and smoking (23). We found LTL was longer in women and blacks, and nonsignificance was likely due to our relatively small sample size. Though there is a potential for survival bias when studying older individuals, this survival bias would most likely have the effect of truncating the distribution of telomere length at the short end and disease at the high end. If the association was weaker or stronger at the extremes or if there was a threshold, we would have less power to detect it. Therefore, the reported associations here are likely to be conservative. Studies across a wider age range could be more powerful. Carotid thickness is a continuous variable and depicts a wider range of disease than dichotomous classification of yes/no presence of disease—subsequently, it is also possible that we identified a significant association of LTL to carotid thickness but not diagnosed coronary disease or cerebrovascular disease due to differences in power. The rich data available in the CHS allowed us to adjust for confounders identified in the literature, but we acknowledge that residual confounding is possible. Finally, because the CHS is a general cohort study of community-dwelling older adults, the results may be relatively generalizable, though they should be replicated in other larger samples, particularly to achieve a higher prevalence of some rarer diagnosed chronic conditions like cerebrovascular disease and kidney disease and in younger individuals to see if this association persists in midlife, which may increase confidence in LTL’s ability to record aging or pathogenesis of age-related disease across the life span.

In conclusion, we found that LTL was strongly associated with disease burden and less strongly or not at all with disease in individual systems or diagnosed chronic conditions. Research that employs more encompassing measures of age-related disease, such as the physiologic index, may be most useful for identifying markers of biologic age.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Royalty Research Fund, the University of Washington, the Healthcare Foundation of New Jersey, the National Institute on Aging (grants R01-AG-023629 and 5-P30-AG-024827), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL-80698-01). The CHS is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contracts N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01-HC-15103, N01-HC-45133, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-55222, and U01 HL080295), the National Institute on Aging (grants AG-021593 and AG-020132), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. A full list of participating Cardiovascular Health Study investigators and institutions can be found at the study’s website (http://www.chs-nhlbi.org). Role of sponsor(s): The investigators retained full independence in the conduct of this research.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions: conception and design (J.L.S. and A.B.N.); acquisition of data (A.L.F., A.M.A., A.A., M.K., and A.B.N.); analysis and interpretation of data (J.L.S, A.L.F., R.M.B., and A.B.N.); drafting of the manuscript (J.L.S. and A.B.N.); critical revision of the manuscript (J.L.S., A.L.F., R.M.B., A.M.A., A.A., L.F.F., T.B.H., and A.B.N.); statistical analysis (J.L.S. and R.M.B.); obtaining funding (A.L.F., A.A., and A.B.N.); administrative, technical, or materials support (A.B.N.); supervision (A.B.N.). Author access to data: All authors had access to data at all times.

References

- 1.Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(2):557–579. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn EH. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature. 2000;408(6808):53–56. doi: 10.1038/35040500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Zglinicki T, Martin-Ruiz CM. Telomeres as biomarkers for aging and age-related diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5(2):197–203. doi: 10.2174/1566524053586545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt HZ, Atturu G, London NJ, Sayers RD, Brown MJ. Telomere length dynamics in vascular disease: a review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mather KA, Jorm AF, Parslow RA, Christensen H. Is telomere length a biomarker of aging? A review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(2):202–213. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo DL. Telomere dynamics in aging: much ado about nothing? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(9):963–964. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Kimura M, Kim S, et al. Longitudinal versus cross-sectional evaluations of leukocyte telomere length dynamics: age-dependent telomere shortening is the rule. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(3):312–319. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waterer GW, Wan JY, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Airflow limitation is underrecognized in well-functioning older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(8):1032–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, et al. Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Heart Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Circulation. 1993;88(3):837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longstreth WT, Jr., Manolio TA, Arnold A, et al. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 1996;27(8):1274–1282. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt MC, Simonsick EM. for the Health ABC Collaborative Research Group. Walking performance and cardiovascular response: associations with age and morbidity—The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(8):715–720. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.8.m715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuller LH, Shemanski L, Psaty BM, et al. Subclinical disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1995;92(4):720–726. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enright PL, McBurnie MA, Bittner V, et al. The 6-min walk test: a quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest. 2003;123(2):387–398. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Cushman M, et al. Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. JAMA. 2005;293(14):1737–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.14.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman AB, Boudreau RM, Naydeck BL, et al. A physiologic index of comorbidity: relationship to mortality and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(6):603–609. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.6.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuller LH, Arnold AM, Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. White matter grade and ventricular volume on brain MRI as markers of longevity in the cardiovascular health study. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(9):1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Wolfson SK, Jr, et al. Use of sonography to evaluate carotid atherosclerosis in the elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1991;22(9):1155–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.9.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barzilay JI, Kronmal RA, Gottdiener JS, et al. The association of fasting glucose levels with congestive heart failure in diabetic adults ≥65 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(12):2236–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried LF, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Kidney function as a predictor of noncardiovascular mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(12):3728–3735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longstreth WT, Jr, Dulberg C, Manolio TA, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of brain infarcts defined by serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2002;33(10):2376–2382. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032241.58727.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(7):1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Gardner JP, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):14–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura M, Stone RC, Hunt SC, et al. Measurement of telomere length by the Southern blot analysis of the terminal restriction fragment lengths. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1596–1607. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins MW, Enright PL, Kronmal RA, et al. Smoking and lung function in elderly men and women: the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 1993;269(21):2741–2748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP. Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clin Chem. 1997;43(1):52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orme J, Reis J, Herz E. Factorial and discriminate validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(1):28–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1<28::aid-jclp2270420104>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, Martire LM, Ariyo AA, Kop WJ. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1761–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdi H. Part (semi partial) and partial regression coefficients. In: Salkind N, editor. Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. pp. 736–740. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aviv A, Chen W, Gardner JP, et al. Leukocyte telomere dynamics: longitudinal findings among young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt SC, Chen Wei, Gardner JP, et al. Leukocyte telomeres are longer in African Americans than in whites: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study and the Bogalusa Heart Study. Aging Cell. 2008;7(4):451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Donnell CJ, Demissie S, Kimura M, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and carotid artery intimal media thickness: the Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(6):1165–1171. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.154849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benetos A, Gardner JP, Zureik M, et al. Short telomeres are associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43(2):182–185. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113081.42868.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bekaert S, De Meyer T, Rietzschel ER, et al. Telomere length and cardiovascular risk factors in a middle-aged population free of overt cardiovascular disease. Aging Cell. 2007;6(5):639–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samani NJ, Boultby R, Butler R, Thompson JR, Goodall AH. Telomere shortening in atherosclerosis. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):472–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05633-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105(13):1541–1544. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthews C, Gorenne I, Scott S, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cells undergo telomere-based senescence in human atherosclerosis: effects of telomerase and oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2006;99(2):156–164. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000233315.38086.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brouilette S, Singh RK, Thompson JR Goodall AH, Samani NJ. White cell telomere length and risk of premature myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(5):842–846. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000067426.96344.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brouilette SW, Moore JS, McMahon AD, et al. Telomere length, risk of coronary heart disease, and statin treatment in the West of Scotland Primary Prevention Study: a nested case–control study. Lancet. 2007;369(9556):107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demissie S, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Insulin resistance, oxidative stress, hypertension, and leukocyte telomere length in men from the Framingham Heart Study. Aging Cell. 2006;5(4):325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valdes AM, Dear IJ, Gardner J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length is associated with cognitive performance in healthy women. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(6):986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grodstein F, van Oijen M, Irizarry MC, et al. Shorter telomeres may mark early risk of dementia: preliminary analysis of 62 participants from the Nurses’ Health Study. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(2):e1590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Zglinicki T, Serra V, Lorenz M, et al. Short telomeres in patients with vascular dementia: an indicator of low antioxidative capacity and a possible risk factor? Lab Invest. 2000;80(11):1739–1747. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zekry D, Herrmann FR, Irminger-Finger I, et al. Telomere length is not predictive of dementia or MCI conversion in the oldest old. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(4):719–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Kluse M, et al. Telomere length and cognitive function in community-dwelling elders: findings from the Health ABC Study. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;32(11):2055–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]