Liberating the NHS: Developing the Healthcare Workforce, describes a vision of a flexible, adaptable workforce, available in the right numbers, with the skills to respond to the changing needs of patients. However, there is compelling evidence to show that our GP workforce is poorly prepared to deliver this vision.

Primary care is ‘mission critical’ to the NHS. There is an abundance of research,1 which shows that good primary care reduces emergency and elective admission, referrals, and all cause mortality. It provides preventative care and early detection of serious illness, and is associated with high patient satisfaction, low medication use, and care-related costs.

There are 303 million general practice consultations a year in England, which represents 90% of all NHS contact;2 98% of NHS prescriptions are issued from primary care.3 Just a 10% shift of this work to secondary care would overwhelm the entire healthcare system.

RISING DEMAND

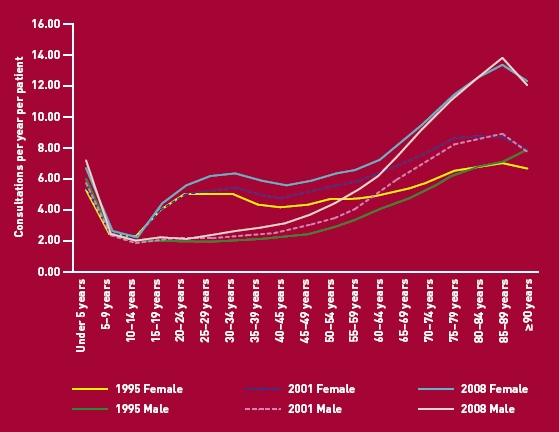

UK general practice is faced with a rapidly ageing population; for example, the number of those aged over 80 years is expected to double between 2010 and 2030. Older patients in this age group consult more frequently: between 12 and 14 times a year in 2008/2009 compared to between six and seven in 1995.2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Historical changes in consultation rate by age group for 1995, 2001, and 2008.6 Reproduced with permission fromQResearch, University of Nottingham.

Increasing complexity has resulted in longer consultations. Each now takes an average 11.7 minutes in 2006/2007 compared to 8.4 minutes in 1992.4

Faced with escalating costs, commissioners are driving a reduction in hospital beds and moving care into more cost-effective ambulatory and community-based settings. The current government's emphasis on long-term conditions in primary care included early intervention and prevention strategies.

CURRENT STATE OF THE WORKFORCE

In the past decade the full-time equivalent GP workforce in England has grown 18% from its 2000 baseline, but in the last Census showed a reduction. In comparison, the number of hospital consultants grew 61% over the same period.5

The growth in GPs in the last decade has been exclusively among salaried GPs, with the number of principals falling significantly. Salaried GPs take more career breaks and work on average 30% fewer clinical sessions than principals, reducing their career participation in the GP workforce significantly.

The Centre for Workforce Intelligence's (CfWI) projections for the GP workforce in England are not encouraging. The supply of newly qualified GPs is unlikely to match demand without international recruits and returners to the GP workforce.6 A retirement bulge looms with 13% of GPs intending to retire in the next 2 years, of whom one-quarter is aged under 58 years; 26% of the GP workforce is hoping to retire in the next 5 years.7 Ten years ago 17% of the GP workforce was aged over 55 years, in 2010 this had increased to 22%. Changes to the NHS pension scheme and the introduction of revalidation are likely to accelerate further the loss of senior GPs.

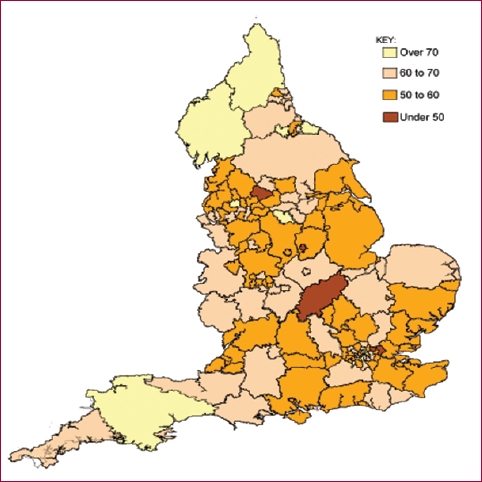

The distribution of the GP workforce has never been equitable. Primary care trusts with the highest GP provision have almost twice the number of GPs per 100 000 patients compared with areas with the fewest doctors per capita. The impact of any GP workforce shortages will, as ever, be most keenly felt in isolated or deprived communities.8 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Full-time equivalent GPs per 100 000 population in England at September 2010 (excluding registrars and retainers), based on data produced by the NHS Information Centre.Weighted by age, sex, and health needs.

One early indicator of workforce undersupply is the long-term GP vacancy rate. Data for 2010 showed that this had increased during the previous 12 months but, somewhat alarmingly, the survey has now been suspended.

While the oft-described shift of care traditionally provided by doctors to other clinicians may well be true, recent workforce surveys actually record a decrease in the number of qualified nurses working in primary care.5 This may in turn be due to changes in skill mix and the employment of healthcare assistants; although this important issue remains poorly researched.

The CfWI recommends a 17% increase of recruitment into GP speciality training to be phased over the next 4 years. As the output from UK foundation schools is expected to remain static, this will necessitate an equivalent reduction in recruitment into training in the hospital specialities.

This presents postgraduate deaneries with two problems:

finding sufficient high quality applicants for GP training; and

identifying funding for the GP expansion if deaneries remain unable to disestablish secondary care training posts and recycle the money into GP training.

Because of reduced international medical immigration at training grade level, the UK now struggles to recruit to the numbers that the CfWI advises.

SOLUTIONS

Only about 20% of recent medical graduates indicate that general practice is their first choice of medical career.9 Different medical schools vary in the aspirations of their graduates. Fewer than 11% of those from Oxford initially choose a career in primary care, whereas over 31% of those from the Peninsula Medical School do. Why is this? Does it relate to differing criteria used for medical student selection, the prominence of primary care in undergraduate curricula, or to the quality of such placements? The General Medical Council and Higher Education Funding Council for England have important roles in incentivising general practice and psychiatry paths in oversubscribed disciplines such as surgery.

It is an aspiration that all foundation trainees should spend at least 4 months working in a primary care setting. Unfortunately this has been difficult to realise in most parts of the UK. Funding difficulties, the need to maintain hospital service delivery, and compliance with European working time regulations trump educational and workforce issues time and again.

Many doctors are known to choose general practice later in their careers, after sampling (and rejecting) one or more secondary care disciplines. While the modernising medical careers initiative has restricted such opportunities, some 500 more experienced doctors move into GP speciality training each year. Proposed initiatives to allow the prior recognition of competences acquired in previous training programmes, and hence some reduction in the duration of GP training, might facilitate such late moves.

Because GP registrars training in general practice settings are deemed to provide no service component; the cost to the NHS of such placements is higher than for those in hospital. In the first financial year of a transition to training more GPs and fewer hospital specialists it is estimated that four ST1/CT1 hospital posts need to be disestablished to support one in general practice. While solutions such as the recognition of service delivery by senior trainees (with a contribution to their salary by the host practice) are superficially attractive, the supernumerary nature of such placements allows for a uniquely intense educational experience; something necessary to offset the relatively short training programme for general practice.

A difficult and perhaps unpalatable truth remains. To develop the primary care workforce the UK so clearly requires, the NHS urgently needs to reduce competing training places in disciplines where there is little anticipated need for new specialists. This will have an impact on secondary care wherever the service is dependent on rotas staffed by trainees and this may in turn drive hospital reconfiguration. However, a future in which a patient suffering from an acute medical illness is diagnosed and admitted to hospital by a fully trained GP, and is then treated by a specialist, rather than a partially trained hospital trainee, is one that will perhaps be more acceptable to patients and politicians than we think.

Provenance

Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344(8930):1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Information Centre. Trends in consultation rates in general practice 1995/6 to 2008/9: analysis of the QResearch® database. London: QResearch® and The Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Audit Office. Prescribing costs in primary care. London: NAO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Information Centre. GP workload survey. The Information Centre; 2007. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/gpworkload (accessed 7 Mar 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Information Centre. Workforce. The Information Centre; http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/workforce (accessed 7 Mar 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centre for Workforce Intelligence. Medical speciality fact sheet — general practice. London: CfWI; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Policy and Economic Research Unit. National survey of GP opinion 2011. London: British Medical Association; 2011. http://www.bma.org.uk/images/gpnationalsurveyresults2011_v2_tcm41-210046.pdf (accessed 7 Mar 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibbald B. Putting general practitioners where they are needed: an overview of strategies to correct maldistribution. Manchester: National Primary Care Research and Development Centre, University of Manchester; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert T, Goldacre M. Trends in doctors' early career choices for general practice in the UK: longitudinal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(588):397–403. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X583173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]