Abstract

A fluorescent voltage sensor protein “Flare” was created from a Kv1.4 potassium channel with YFP situated to report voltage-induced conformational changes in vivo. The RNA virus Sindbis introduced Flare into neurons in the binocular region of visual cortex in rat. Injection sites were selected based on intrinsic optical imaging. Expression of Flare occurred in the cell bodies and dendritic processes. Neurons imaged in vivo using two-photon scanning microscopy typically revealed the soma best, discernable against the background labeling of the neuropil. Somatic fluorescence changes were correlated with flashed visual stimuli; however, averaging was essential to observe these changes. This study demonstrates that the genetic modification of single neurons to express a fluorescent voltage sensor can be used to assess neuronal activity in vivo.

Keywords: single cell, cortex, two-photon imaging, genetic engineering, vision

Introduction

Functional neural circuits have been extensively explored in early sensory areas with a confluence of electrophysiological and neuroanatomical methods. Although electrical recordings in vivo are arguably responsible for the bulk of our understanding of higher cortical areas, combining the morphological, biochemical, and genetic identity of neurons in combination with the multiplicities of function has been challenging. Recent improvements permit neurons to be more selectively labeled and imaged in vivo (Ohki et al., 2005; Ch'ng and Reid, 2011) by the extracellular application of a membrane-permeant calcium dye Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB) in mouse sensory cortex (Stosiek et al., 2003; Mrsic-Flogel et al., 2007). However, this type of calcium labeling has limitations. The dye fades over time and may compromise cell health over repeated applications and thus is not useful in long-term preparations. Furthermore, OGB stains all types of neuron and thus does not allow specific examination of certain neuron types unless it is combined with genetical labeling of specific neuron types (Sohya et al., 2007). On the other hand, calcium dyes like OGB produce a stronger and faster signal compared to various genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECI) (Hendel et al., 2008).

Crick proposed that molecular biology would permit access to particular neuronal types (Crick, 1979). Only more recently has the technology to perform single neuron genetics become available with the advent of retroviruses and other vectors that can control the expression of proteins in vivo (Xiao et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2000; Wickersham et al., 2007). Selection of neurons versus glia, or different types of neuron has become possible either through choice of virus or viral serotype that are selectively neurotropic (Nathanson et al., 2009a,b; Marshel et al., 2010). As well, the control of the expression of reporter genes has matured through development of novel promoters (Reiff et al., 2005).

Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors can be designed to detect various changes related to neural activity: reporters of intracellular Ca2+, for example, Cameleon (Reiff et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2008), or sensors reporting changes in membrane voltage (Baker et al., 2008; Perron et al., 2009b; Lundby et al., 2010). One of the first generation voltage sensors was Fluorescent Shaker (FlaSh), which is a fusion of a voltage-gated Shaker K+ channel and a green fluorescent protein (GFP). The dynamics of FlaSh should allow detection of single electrical events. However, in vivo such temporal precision is not possible due to presence of background noise (Siegel and Isacoff, 1997; Guerrero et al., 2002). Another second-generation sensor SPARC (sodium channel protein-based activity reporting construct) was also reported to show fast kinetics and reliably report short depolarizing pulses as short as 2 ms (Ataka and Pieribone, 2002).

These sensors have been tested extensively in vitro and in cultured neurons but not in vivo under sensory stimulation (Baker et al., 2007). For the current study, neurons in rat visual cortex were transfected to express Flare and imaged in vivo. The study by Baker et al. (2007) reported no functional signals in dissociated hippocampal neurons or HEK 293 cells expressing Flare, whereas the current study showed significant responses in a relatively small percentage of neurons. Differences in expression between species (e.g., rats vs. mice) might be responsible for such discrepancy (Xu et al., 2006; Xu and Callaway, 2009). As a first step toward neural circuit analysis in larger animals such as non-human primates (Heider et al., 2010), the voltage sensor called Flare, was assessed in a rodent model using two-photon scanning microscopy (TPSM) as described previously (Denk et al., 1994; Jung et al., 2004; Levene et al., 2004). These results demonstrate the feasibility of the sensor and method and thus open the possibility to use similar sensors in other species. This work has been presented in abstract form (Siegel et al., 2007).

Materials and methods

All experiments were carried out according to NIH Guidelines for Animal Research and approved by Rutgers University Animal Care and Facilities Committee. All procedures followed the guidelines for rodent survival and non-survival surgery.

Sensor

The Flare fluorescent voltage sensor is a Kv1.4 variant of FlaSh (Siegel and Isacoff, 1997; Guerrero et al., 2002). By design, Flare is sensitive to supra-threshold events. Flare was created starting with a Kv1.4 potassium channel. The Flare channel was further modified to not pass current by altering amino acid W517F. The linear range for dF/voltage of Flare was –50 to –10 mV based on the rational design virus. The distribution of the Flare protein may be similar to the native Kv1.4, which is concentrated with PSD-95 (Walikonis et al., 2000). There is some differential distribution of the related Kv1.2 in dendrites of pyramidal cells (Sheng et al., 1994), but this distribution varied with cell type throughout the central nervous system with some cells showing expression in axonal terminals and the soma. Enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) was inserted between V584A and S585S in Kv1.4. The sequence for Flare was inserted into Sindbis plasmids and virus generated in order to transfect neurons in rat cortex.

Animal surgery and virus injection

In a first recovery surgery, Sprague–Dawley rats (200–800 g) were anesthetized using ketamine (50 mg/kg), acepromazine (0.5 mg/kg), xylazine (5 mg/kg) IP. Atropine (0.05 mg/kg, SC) and bupivacaine (0.2 ml, SC) were administered. A thin layer of ophthalmic ointment was applied on the eyes to avoid dehydration. Anesthesia was maintained by injections of the ketamine mixture every 30 min. The skull was thinned bilaterally exposing the cortex from 4 mm to 8 mm posterior of Bregma, and 2 mm to 6 mm lateral. A drop of sterile saline was placed on the skull to reduce light scattering, clearly revealing cortical blood vessels. An imaging chamber was constructed using a 3 × 5 mm cover slip and orthopedic cement (Smith and Nephews, Richards, Memphis, TN). The chamber was filled with sterile 1% agar in 0.9% saline and sealed with cement and bone wax.

After conclusion of the intrinsic imaging experiment, the remaining thinned skull was opened completely. The dura was nicked at the injection locations to allow the glass pipette (10 μm tip diameter) to be lowered into the cortex. A total amount of 1–2 μl Sindbis Flare was injected using a Picospritzer pressure system. One to five injections were made into the cortex at depths ranging from 1000 μm to the surface. Locations were selected based upon the cortical activation maps and scarcity of blood vessels. Bilateral injections were made in most cases. The muscle and skin tissue was pulled over the craniotomy and the skin stapled. Antibiotic ointment and a local anesthetic were applied on the skin margin, and the animal allowed recovering in its home cage.

Eighteen to Thirty-six hours after the injection procedure, the animal was anesthetized again for a non-survival surgery, and placed in a modified stereotaxic device for two-photon imaging. The same anesthesia drugs were used as for the survival surgery, as described previously. The incision was reopened and the dura completely resected to expose the cortex. Grounding and reference screws were attached to the skull, and a monopolar electrode placed onto the cortical surface within 1 mm of the recording site. This allowed simultaneous recordings of visually evoked potential during the scanning. An imaging chamber was constructed again with agar, a glass cover, orthopedic cement and bone wax, as described above. The stereotaxic device with the rat was placed under the two-photon scanning microscope. At the end of the experiment (3–5 h), an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (125 mg/kg IP) was administered and standard transcardial perfusion with 4% formalin in saline was performed.

Confocal images of fixed sections were obtained using a BioRad MRC-1024 laser-scanning microscope. Intensity profiles of confocal images were calculated using the “plot profile” procedure (line selections) of ImageJ Software (version 1.38; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Intrinsic imaging and two-photon scanning

Intrinsic optical imaging was performed according to previously published principles for non-human primates (Siegel et al., 2003; Heider et al., 2005) with slight modifications for rodents. A custom built macroscope was utilized with an Optical Imaging 2001 system (Optical Imaging Co., Rehovot, Israel). The vasculature was visualized using 540 nm green light to determine the depth of the cortical surface. Illumination for intrinsic signal imaging was at 605 nm after focusing down 300 μm from the surface. Rats were fitted with goggles made from adjustable material to eliminate light leakage from the visual stimulus. Visual stimulation was provided via a combination of four miniature LEDs (E100; Gilway, Woburn, MA): red (625 nm), blue (465 nm), violet (420 nm), and ultraviolet (375 nm). These wavelengths were chosen to cover the entire range to which rat photoreceptors are selective (Jacobs et al., 2001). The light was passed through a fiber optic that was directly apposed to the cornea providing full field illumination in one eye. After a baseline period of 1000 ms, the stimulus was switched on for 500 ms and then turned off. Images were collected at 7 Hz for a total duration of 5200 ms. The data were converted into the Khoros (Khoral Inc., Albuquerque, NM) format and regions of interest (ROI) were analyzed. Signals were expressed as percentage changes from baseline, which consisted of the 500 ms before stimulus onset.

The two-photon scanning microscope was custom-built according to published design (Tsai et al., 2002). A Mai Tai Ti:sapphire Laser (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA) tunable from 700 to 1020 nm projected a beam into a double telescope to reshape it, a half-wave plate and polarizing beam splitter to alter the power of the beam, galvanometer scanning mirrors and drivers (Cambridge Technology, Cambridge, MA), scanning and tube lenses, and dichroic mirrors (720DCXXR dichroic, HQ535/40-2P emission; Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT). The laser was blocked between trials using a mechanical Uniblitz shutter. The two-photon microscope was fitted with either a 60× LUM Plan 0.9 NA (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) or a 40× Plan-Neofluar 0.8 NA (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) water immersion objective. For excitation of the EYFP an emission wavelength of 920 nm was used. Photons emitted by fluorescent sensor were measured with a photomultiplier tube (PMT) modules (H7710–13; Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). Current was converted to voltage using a low-noise current preamplifier (model SR570, Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA) and digitized with a National Instruments A–D converter. The scanning signals and the A–D converter were controlled and synchronized using Labview-based software (Nguyen et al., 2006). The stored binary image files were analyzed offline using Khoros Package (AccuSoft Corporation, Northborough, MA) in conjunction with custom Unix shell software. ROIs were selected and averages of the pixels within the ROIs were calculated.

Once a field of neurons was located, a high-resolution structural image was acquired (512 × 512 pixels). For functional imaging, scanning was performed at higher frequency and lower spatial resolution. To analyze the evoked responses, the stimulus was presented at variable ON-OFF periods (20–20, 10–30, 30–10; in frames). Evoked responses were defined as percentage change between ON and OFF responses.

ROIs were selected using an automated analysis of labeled regions. The average was computed for a single trial. The mean and standard deviation of the fluorescence signal was computed on a pixel-by-pixel basis for each experimental scan (∼100 trials). The image was then subjected to a threshold so that all pixels greater than one standard deviation above the mean were indicated. The resulting image was then passed through procedures “vlabel” and “vshape” of the Khoros package to select and reduce the number of regions. Subsequently, the same baseline normalization and statistical analyses were performed. In a few experiments, a manual approach was applied as well to compare and verify the automatic region selection. Rectangular regions containing either neurons or neuropil were delimited by eye and the averaged changes in fluorescence of each manually determined ROI calculated. To assess the responses of each ROI, the average fluorescence during the OFF phase was compared with the fluorescence during the ON phase using a One-Way ANOVA with the type of phase as a categorical variable.

Results

The main goal of the present study was to examine the structural appearance and functional properties of the genetically encoded fluorescent voltage sensor Flare. Neurons in rat visual cortex were transfected with Sindbis Flare to assess neural activity to visual stimulation in vivo.

Structural imaging: expression of Sindbis flare

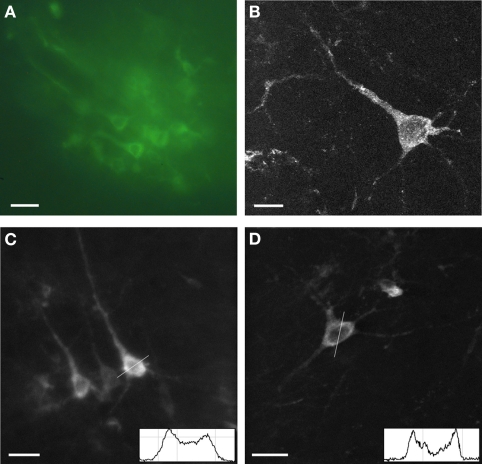

The expression of Sindbis Flare was examined first in fixed tissue (Figure 1). Fields of neurons from superficial cortex approximately 10–50 μm in diameter were easily identified under a conventional fluorescence microscope (Figure 1A). Confocal images of individual neurons confirm that the sensor fluorescence accumulated in the cytosol and in the plasma membrane (Figures 1B–D). Fluorescence intensity profiles (insets in Figures 1C,D) for two selected neurons illustrate that labeling in the plasma membrane was indeed brighter compared to the cytosol, as shown previously (Baker et al., 2007). Fine processes were rarely visible and third order dendrites were never observed. The presence of Flare in the dendrites is as expected given its Kv1.4 origins. The appearance of the labeled neurons suggests that mostly pyramidal neurons were labeled.

Figure 1.

Expression of Sindbis Flare in fixed tissue. (A) Fluorescence microscope image of field of labeled neurons. (B) High power confocal image of a single neuron transfected with Flare (10 μm stack, 0.5 micron sections). (C,D) Confocal images of labeled neurons. No more than third-order dendrites are labeled. Insets show gray scale profiles (membrane brightness relative to cell plasma: 44%, A; 83%, B; distance; 25 μm) across selected cell bodies. Scale bars, 10 μm (A), 5 μm (B), 20 μm (C,D).

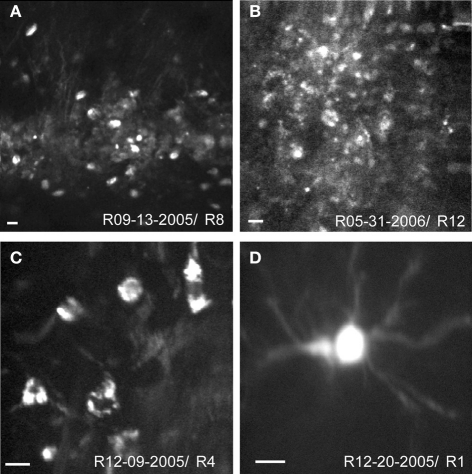

Structural images of neurons were obtained with TPSM in vivo in rat cortex 12–36 h after viral transfection. Low magnification images illustrate the extent of the transformed tissue (Figures 2A,B) and single neurons are visualized at higher magnification (Figures 2C,D). While cell bodies were easily imaged in vivo, cell processes were only rarely observed (Figures 2A,D). There were many instances where the background was labeled (Figure 2B), which likely consisted of optically inseparable small processes of the neuropil. The appearance of the sensor with predominant membrane labeling (compare to Figure 1) was rarely seen in vivo (Figure 2C). The Flare signal dropped off rapidly with increasing cortical depth, with signals rarely detectible deeper than 350 μm. This limitation results from a combination of factors, including available laser power, laser pulse width, efficiency of the detection optics, opacity, and light scattering properties of the tissue. The range of depths for all experiments was between 90 and 350 μm with the majority of experiments performed at depths between 100 and 200 μm.

Figure 2.

In vivo structural two-photon scanning of Sindbis Flare transfected neurons in rat visual cortex. (A,B) Labeled cell bodies and neuropil at low magnification. (C,D) High magnification images of soma and dendrites. Scale bars, 10 μm. Depth of scanning for each example was 90 μm (A), 100 μm (B), 120 μm (C), 340 μm (D).

Functional imaging: stimulus evoked signals

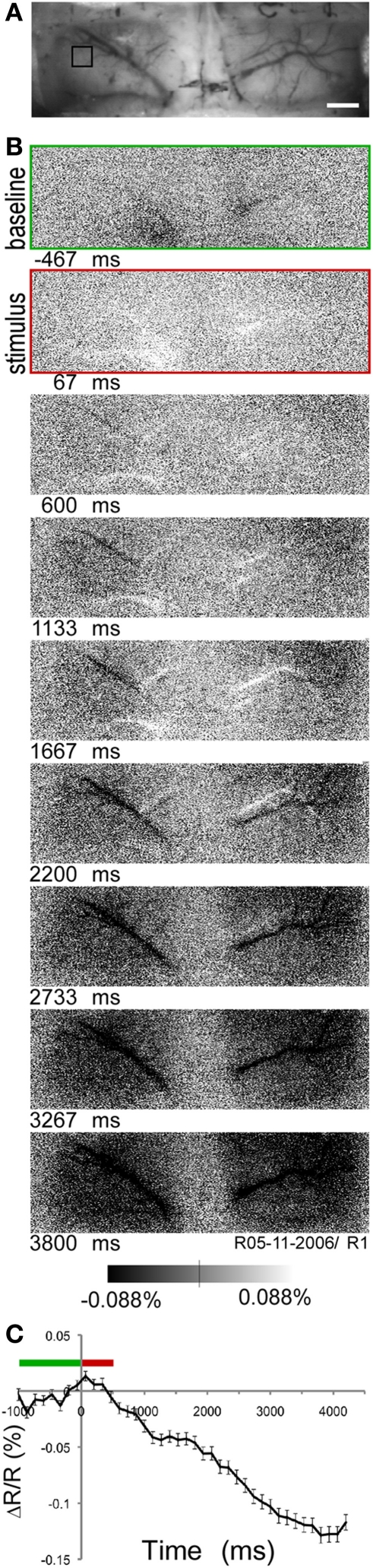

In 17 of 44 rats, intrinsic imaging was performed prior to the Sindbis Flare injection to optimally target the injection locations in visual cortex (Figure 3A). To measure the intrinsic, hemodynamic signal of the cortex related to a visual stimulus, a short 500 ms period of monocular, full field ON stimulation was followed by a longer OFF period (3700 ms), and the tissue reflectance measured at 605 nm illumination. In the majority of cases (13/17), the reflectance decreased throughout the measurement period (Figures 3B,C), which manifested as a continuous darkening of the cortex. This is indicative of an overall increase in HbR (deoxyhemoglobin) that can last up to 3000 ms after stimulus onset (Blood et al., 1995; Martin et al., 2006; Simons et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011). The locations for the Sindbis Flare injections were based on examination of the intrinsic signal, that is, locations with a strong hemodynamic response and an absence of larger blood vessels were preferred for the subsequent Sindbis Flare injections.

Figure 3.

Intrinsic optical imaging of rat visual cortex. (A) Image taken under green (540 nm) light to visualize vasculature over visual cortex through thinned skull. Scale bar, 1 mm. (B) Time series of intrinsic images taken at 7 Hz under orange (605 nm) light. First image, baseline period (green); second image, visual stimulation period (red) (C) Time course (mean ± standard error) of intrinsic signal in region of interest indicated in (A, black square). Green bar, baseline period; red bar, stimulation period (stimulus onset at time 0).

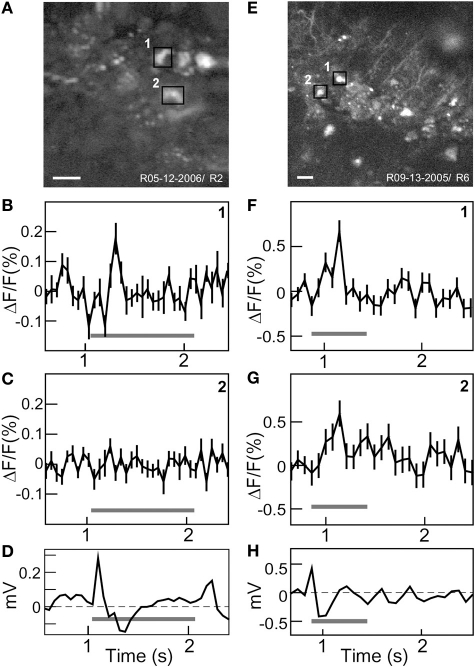

To establish the functionality of the voltage sensor, Flare expressing neurons in rat visual cortex were stimulated with periodic full field visual stimulation. Two examples were chosen to illustrate the typical response of labeled neurons. A high spatial resolution TPSM image of labeled neurons over an 80 × 80 μm region of cortex shows a small cluster of cells (Figure 4A). The time course of fluorescence over brightly labeled ROI were computed by averaging 100 stimulus repetitions. Baseline normalized fluorescence responses for two neighboring neurons are shown. One neuron had a significant ON response at stimulus onset (Figure 4B, p < 0.01), while another cell approximately 10 μm away did not respond (Figure 4C). Simultaneous visually evoked potentials were observed consistently (Figure 4D). The second example shows a 120 × 120 μm field of labeled neurons including labeled processes (Figure 4E). Two selected neighboring neurons showed very similar significant ON responses (Figures 4F,G; p < 0.01). Visually evoked potentials were also recorded (Figure 4H). The Flare signal did not bleach over the 220 s of measurement period, even though the beam was continually scanning.

Figure 4.

In vivo functional two-photon scanning of Sindbis Flare transfected neurons in rat visual cortex. (A) High resolution (256 × 256) structural scan of first site with multiple labeled neurons with two ROIs (black squares) delimited. (B,C) Averaged fluorescence signal (mean ± standard error) from each ROI. Cell 1 responded to stimulus onset (B), cell 2 did not respond (C). Graphs (D) Visually evoked potentials from surface electrode. (E) High resolution (512 × 512) structural scan of second site showing labeled cell bodies and processes. Two neighboring cells are marked (black squares). (F,G) Averaged fluorescence signal (mean ± standard error) for cell 1 and 2 that both show significant responses. (H) Visually evoked potentials. Gray bars in (B–D, F–H) indicate ON stimulus period. Scale bars: 20 μm.

A total of 44 Sindbis Flare in vivo TPSM experiments were performed of which 12 were discarded for various reasons (e.g., bleeding into imaging field, light leakage from stimulus display). Per experiment 2–3 sites were scanned. Each site always contained several identifiable labeled regions or neurons (mean = 10 ± 5) resulting in a total of 2656 ROIs, which were analyzed quantitatively. To obtain visually evoked responses, substantial averaging was needed (∼100 trials per run). Significant ON responses were found in 14.5% of all ROIs, whereas 6.8% had significant OFF responses to the full field visual stimulus.

Discussion

The fluorescent voltage sensor Sindbis Flare was introduced via viral transfection into rat visual cortex to allow in vivo TPSM of individual, labeled neurons. Despite the fact that a previous study reported no functional optical signal using Flare in dissociated hippocampal neurons under patch clamp electrical stimulation (Baker et al., 2007), the current results demonstrate that a substantial proportion of Flare expressing neurons indeed showed significant changes in fluorescence to sensory stimulation. Differences in preparation, species, and imaging technique could well account for these differences.

Rational design of sensor

The original design of Flare was based on the current understanding of the properties of Kv1.4 channel, and was engineered to be linear for the voltage range of –50 to –10 mV. During action potentials, the Flare signal is supposed to saturate at its maximum emission. Based on the time course of Flare from in vitro studies and its voltage selectivity (Guerrero et al., 2002), we interpret the Flare signal as an approximation to the mean firing rate. Both increases and decreases in the fluorescence emission concurrent with stimulus onset and offset were recorded from the labeled neurons in the current study. The fairly slow time course of the fluorescence signal did not allow for the recording of individual action potentials. This is also the case for the more recently developed fluorescent calcium sensors based on the calcium binding protein troponin C (Mank et al., 2008), which demonstrate relatively slow kinetics. Furthermore, the peak change in fluorescence of voltage sensitive dyes and proteins is at least an order of magnitude smaller than the signal observed with typical calcium indicator dyes (Hendel et al., 2008). Whether enough photons can be generated in a time window short enough to resolve individual action potentials by newer voltage or calcium sensors will depend critically on the density of sensor molecules, the efficiency of fluorescence excitation, the degree of modulation of fluorescence by voltage or calcium, and the efficiency of the detectors. Recent developments of the GCamp calcium indicator family show promising temporal resolution and signal to noise ratio (Tian et al., 2009; Looger and Griesbeck, 2011), which might allow detection of individual action potentials from the fluorescence signal. Novel proteins, for example C. intestinalis voltage-sensor-containing phosphatase (Ci-VSP), which translates transmembrane voltage changes into the turnover of phosphoinositides (Murata et al., 2005; Lundby et al., 2010), and microbial rhodopsins (Kralj et al., 2011) offer viable alternatives to the Shaker family with improvements in sensitivity and speed (Mutoh et al., 2011).

In fixed tissue using confocal microscopy, Flare expressing neurons displayed fluorescence labeling in the cell membrane. However, high magnification two-photon images of Flare neurons in vivo mostly revealed cell bodies and occasional processes, whereas the membrane labeling was difficult to detect. It is possible to envision other constructs of Flare that would direct it to particular membrane or peri-membrane locations (Guerrero et al., 2005). Increased density of Flare in the membrane should lead to higher signals, and also might improve signal strength. It is noteworthy in this respect that increased synthesis of Flare alone might not be productive as there could be a high concentration of Flare associated with intracellular membrane, such as the ER. Signal strength might be further affected by functionality of the Kv1.4 channels (Zhu et al., 2003; Jenkins et al., 2011). For example, it is hypothetized that the FlaSh or Flare subunits can co-assemble with compatible native subunits of the Kv1 subfamily (Guerrero et al., 2002). Due to the high levels of expression of Flare expected with Sindbis, it is anticipated that many of the Kv1.4 channels will be either heteromeres with a majority of Flare sub-units, or homomeres. It has been suggested that assemblies of different subunits can produce channels with distinct kinetics and pharmacology (Isacoff et al., 1990).

Vectors for transfection: neuronal specificity

In the current study, Sindbis was used as viral vector for transforming neurons. In cell culture, Sindbis is known to damage cells or cause apoptosis as early as 12 h after infection through NMDA (Nargi-Aizenman and Griffin, 2001). In our hands, Sindbis Flare permits labeling of neurons that may be recorded up to 36 h following transfection. There were few signs of damage to the neurons in this time window including morphological abnormalities or blebbing. Successful transfection of neurons using Sindbis without evidence of cell damage or necrosis more than one day after transfection has been demonstrated previously (Chen et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2004). It may be that the extracellular milieu provides protection to the neurons via circulating anti-oxidant protective factors. This fast expression time period is useful when examining short-term plasticity questions and immediate sensory evoked response properties, but its greatest value may be for the rapid assessment of novel biosensor proteins. Recent developments have generated Sindbis virus with decreased neurotoxicity, which allow longer expression times and viable neurons for up to one week after infection (Jeromin et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2004)

The histology indicates that Sindbis Flare primarily labeled pyramidal neurons in rat cortex, as demonstrated previously using Sindbis EGFP (Chen et al., 2000). We base this conclusion primarily on the morphology of neurons as evidenced in fixed tissue using fluorescence or confocal microscopy. There was no evidence that glial cells were labeled based on the cell morphology. Earlier studies comparing different viral vectors confirm that more than 90% of infected cells showed neuronal morphology (Ehrengruber et al., 1999). Selective expression (i.e., transfection of specific cell types) will allow targeting of neuronal subpopulation and ensure that only neurons are labeled. Recent studies demonstrate that depending on virus type and titer specific neuronal subpopulations can be transfected (Nathanson et al., 2009b). In addition, adeno-associated viruses (AAV) of various serotypes are known to infect different cell types based upon cell surface antigens (Cearley and Wolfe, 2006; Wu et al., 2006; Taymans et al., 2007). Furthermore, cell type specificity may be approached on the basis of neuronal anatomy; retrograde labeling by infecting cells via their axon terminals, can access specific anatomical projection classes (Burger et al., 2004). In addition, cell type specificity has been attempted by inclusion of specific promoters and enhancers (Morelli et al., 1999; Nathanson et al., 2009a). Finally, transgenic mice in which GABA-ergic neurons express GFP further allow labeling and imaging of specific neuron types (Sohya et al., 2007).

Suitability of Sindbis flare as a genetically encoded fluorescence voltage sensor

In the current study, about 15% of labeled cells responded to the onset of the full field visual stimulus composed of several wavelengths. This relatively low number has been commonly observed in genetically encoded fluorescent sensors in cortex, for example, for the virally transfected neurons in mouse visual cortex expressing the calcium sensor TNXXL (Mank et al., 2008).

Several factors can account for this relatively low percentage of responsive neurons. First, the flashed stimulus may have not been optimal. A study of single unit activity using a variety of stimuli in rat visual cortex found that 11% of units responded optimally to uniform stimulation. The majority of cells preferred structured stimuli with low spatial frequencies (Girman et al., 1999). A recent fMRI study in rats found reliable hemodynamic and electrical (multiunit) activation using full-field stimulation with LEDs of varying wavelength (Bailey et al., 2012). In our study, intrinsic optical imaging in rat visual cortex showed reliable functional activation using full field stimuli, which was confirmed by visually evoked potentials (You et al., 2011). Thus, the visual stimulation in the current study was suitable to elicit neural responses but could be further improved by incorporating structured stimuli such as gratings. Second, neural responsiveness also depends on the state of cortex (Hasenstaub et al., 2007), which can be strongly affected by anesthesia, with deep anesthesia significantly blocking signal propagation through a cortical network (Ahrens and Freeman, 2001). Nonetheless, other rodent studies using various forms of anesthesia yielded relatively high percentages of visually responsive neurons (Ohki et al., 2005; Niell and Stryker, 2008). Fluctuations in anesthesia could also be responsible for the observed variability of the intrinsic signal time course (Martin et al., 2006; Devonshire et al., 2010). Third, the relatively small number and substantial averaging needed to extract stimulus-evoked signals may arise from the limited quantity of fluorescent protein that is being imaged; the functional Flare signal is largely obtained from the cell membrane, thus reducing the labeled area that can be scanned.

While the current generation of genetically encoded voltage sensors all have a smaller signal to noise ratio compared to calcium sensors, further development of membrane targeted sensors will likely result in stronger signals to provide reliable measures of neuronal activity. The advantage of voltage-based sensors over calcium sensors is the potential for much faster measurements that could, in principle, permit the detection of single action potentials. In the current and other studies (Akemann et al., 2010) using living animals, the measured increase in fluorescence from visual stimulation showed slower kinetics compared to in vitro studies. The specific kinetics of Flare are not known but different versions of FlaSh have demonstrated large variability in kinetics and signal amplitude (Guerrero et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2011).

Current voltage sensitive dyes provide a strong signal and allow imaging of large neuronal populations (Slovin et al., 2002; Grinvald et al., 2003). Bulk loading is required for applying these dyes and thus does not permit selective targeting of specific neuron types. Similarly, cell permeant calcium indicators are characterized by strong signal and labeling of large numbers of neurons of which up to 75% are responsive (Ohki et al., 2005). Again, the downside is the lack of specificity of the calcium indicator labeling (Sohya et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2007). Thus, one of the main advantages of the genetic encoding approach is the specificity of single neuron molecular genetics. In addition, if using appropriate viral vectors (e.g., AAV), genetically encoded sensors also allow long-term monitoring as they can permanently label neurons without causing cell damage (Heider et al., 2010). Thus, evaluating Sindbis Flare in a rodent model represents a crucial step in improving fidelity of these sensors and allows applications in various species. The current study clearly demonstrates that Sindbis Flare showed superior performance compared to previous reports using preparations such as in vitro studies in dissociated hippocampal neurons. Thus, sensors of newer generations need to be evaluated using a variety of preparations and species (Perron et al., 2009a; Jin et al., 2011).

Genetically encoded sensors of both voltage and calcium will allow further advances as the means to select the transformed neuronal population develop. Neuronal populations can be selected using anterograde (Chamberlin et al., 1998) and retrograde (Lu et al., 2003) transfection. Similarly, a modified rabies vector permits labeling based on connectivity (Wickersham et al., 2007). These molecular approaches applied to systems neuroscience, as predicted by Francis Crick 30 years ago (Crick, 1979), will transform our view of the role of the circuit in generating perception and action.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Initial assistance in our two-photon imaging efforts by Samar Mehta, Phil Tsai, and David Kleinfeld are gratefully appreciated. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants EY-R03EY014657 (RMS), R01NS050833 (EYI, RMS), The Whitehall Foundation (RMS), National Science Foundation Grant NPACI RUT223 (RMS).

References

- Ahrens K. F., Freeman W. J. (2001). Response dynamics of entorhinal cortex in awake, anesthetized, and bulbotomized rats. Brain Res. 911, 193–202 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02687-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akemann W., Mutoh H., Perron A., Rossier J., Knöpfel T. (2010). Imaging brain electric signals with genetically targeted voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 7, 643–649 10.1038/nmeth.1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataka K., Pieribone V. A. (2002). A genetically targetable fluorescent probe of channel gating with rapid kinetics. Biophys. J. 82, 509–516 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75415-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C. J., Sanganahalli B. G., Herman P., Blumenfeld H., Gjedde A., Hyder F. (2012). Analysis of time and space invariance of BOLD responses in the rat visual system. Cereb. Cortex. [Epub ahead of print] 10.1093/cercor/bhs008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B., Mutoh H., Dimitrov D., Akemann W., Perron A., Iwamoto Y., Jin L., Cohen L., Isacoff E., Pieribone V., Hughes T., Knöpfel T. (2008). Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors of membrane potential. Brain Cell Biol. 36, 53–67 10.1007/s11068-008-9026-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B. J., Lee H., Pieribone V. A., Cohen L. B., Isacoff E. Y., Knöpfel T., Kosmidis E. K. (2007). Three fluorescent protein voltage sensors exhibit low plasma membrane expression in mammalian cells. J. Neurosci. Methods 161, 32–38 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blood A. J., Narayan S. M., Toga A. W. (1995). Stimulus parameters influence characteristics of optical intrinsic signal responses in somatosensory cortex. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 15, 1109–1121 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C., Gorbatyuk O. S., Velardo M. J., Peden C. S., Williams P., Zolotukhin S., Reier P. J., Mandel R. J., Muzyczka N. (2004). Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol. Ther. 10, 302–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley C. N., Wolfe J. H. (2006). Transduction characteristics of adeno-associated virus vectors expressing cap serotypes 7, 8, 9, and Rh10 in the mouse brain. Mol. Ther. 13, 528–537 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'ng Y. H., Reid C. (2011). Cellular imaging of visual cortex reveals the spatial and functional organization of spontaneous activity. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 4:20 10.3389/fnint.2010.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin N. L., Du B., De Lacalle S., Saper C. B. (1998). Recombinant adeno-associated virus vector: use for transgene expression and anterograde tract tracing in the CNS. Brain Res. 793, 169–175 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00169-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. E., Lendvai B., Nimchinsky E. A., Burbach B., Fox K., Svoboda K. (2000). Imaging high-resolution structure of GFP-expressing neurons in neocortex in vivo. Learn. Mem. 7, 433–441 10.1101/lm.32700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F. (1979). Thinking about the brain. Sci. Am. 241, 219–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk W., Delaney K. R., Gelperin A., Kleinfeld D., Strowbridge B. W., Tank D. W., Yuste R. (1994). Anatomical and functional imaging of neurons using 2-photon laser scanning microscopy. J. Neurosci. Methods 54, 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devonshire I. M., Grandy T. H., Dommett E. J., Greenfield S. A. (2010). Effects of urethane anaesthesia on sensory processing in the rat barrel cortex revealed by combined optical imaging and electrophysiology. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32, 786–797 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz L. M., Maiya R., Sullivan M. A., Han Y., Walton H. A., Boehm S. L., Bergeson S. E., Mayfield R. D., Morrisett R. A. (2004). Sindbis viral-mediated expression of eGFP-dopamine D1 receptors in situ with real-time two-photon microscopic detection. J. Neurosci. Methods 139, 25–31 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrengruber M. U., Lundstrom K., Schweitzer C., Heuss C., Schlesinger S., Gähwiler B. H. (1999). Recombinant Semliki Forest virus and Sindbis virus efficiently infect neurons in hippocampal slice cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7041–7046 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girman S. V., Sauve Y., Lund R. D. (1999). Receptive field properties of single neurons in rat primary visual cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 82, 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A., Arieli A., Tsodyks M., Kenet T. (2003). Neuronal assemblies: single cortical neurons are obedient members of a huge orchestra. Biopolymers 68, 422–436 10.1002/bip.10273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero G., Rieff D. F., Agarwal G., Ball R. W., Borst A., Goodman C. S., Isacoff E. Y. (2005). Heterogeneity in synaptic transmission along a Drosophila larval motor axon. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1188–1196 10.1038/nn1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero G., Siegel M. S., Roska B., Loots E., Isacoff E. Y. (2002). Tuning FlaSh: redesign of the dynamics, voltage range, and color of the genetically encoded optical sensor of membrane potential. Biophys. J. 83, 3607–3618 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75361-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenstaub A., Sachdev R. N. S., McCormick D. A. (2007). State changes rapidly modulate cortical neuronal responsiveness. J. Neurosci. 27, 9607–9622 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2184-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider B., Jando G., Siegel R. M. (2005). Functional architecture of retinotopy in visual association cortex of behaving monkey. Cereb. Cortex 15, 460–478 10.1093/cercor/bhh148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider B., Nathanson J. L., Isacoff E. Y., Callaway E. M., Siegel R. M. (2010). Two-photon imaging of calcium in virally transfected striate cortical neurons of behaving monkey. PLoS One 5:e13829 10.1371/journal.pone.0013829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendel T., Mank M., Schnell B., Griesbeck O., Borst A., Reiff D. F. (2008). Fluorescence changes of genetic calcium indicators and OGB-1 correlated with neural activity and calcium in vivo and in vitro. J. Neurosci. 28, 7399–7411 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1038-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isacoff E. Y., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1990). Evidence for the formation of heteromultimeric potassium channels in Xenopus oocytes. Nature 345, 530–534 10.1038/345530a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs G. H., Fenwick J. A., Williams G. A. (2001). Cone-based vision of rats for ultraviolet and visible lights. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 2439–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins P. M., McIntyre J. C., Zhang L., Anantharam A., Vesely E. D., Arendt K. L., Carruthers C. J. L., Kerppola T. K., Iñiguez-Lluhí J. A., Holz R. W., Sutton M. A., Martens J. R. (2011). Subunit-dependent axonal trafficking of distinct α heteromeric potassium channel complexes. J. Neurosci. 31, 13224–13235 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0976-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeromin A., Yuan L.-L., Frick A., Pfaffinger P., Johnston D. (2003). A modified sindbis vector for prolonged gene expression in neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 2741–2745 10.1152/jn.00464.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L., Baker B., Mealer R., Cohen L., Pieribone V., Pralle A., Hughes T. (2011). Random insertion of split-cans of the fluorescent protein venus into Shaker channels yields voltage sensitive probes with improved membrane localization in mammalian cells. J. Neurosci. Methods 199, 1–9 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. C., Mehta A. D., Aksay E., Stepnoski R., Schnitzer M. J. (2004). In vivo mammalian brain imaging using one- and two-photon fluorescence microendoscopy. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 3121–3133 10.1152/jn.00234.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Dittgen T., Nimmerjahn A., Waters J., Pawlak V., Helmchen F., Schlesinger S., Seeburg P. H., Osten P. (2004). Sindbis vector SINrep(nsP2S726): a tool for rapid heterologous expression with attenuated cytotoxicity in neurons. J. Neurosci. Methods 133, 81–90 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralj J. M., Douglass A. D., Hochbaum D. R., Maclaurin D., Cohen A. E. (2011). Optical recording of action potentials in mammalian neurons using a microbial rhodopsin. Nat. Methods 9, 90–95 10.1038/nmeth.1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levene M. J., Dombeck D. A., Kasischke K. A., Molloy R. P., Webb W. W. (2004). In vivo multiphoton microscopy of deep brain tissue. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 1908–1912 10.1152/jn.01007.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Gong H., Li X., Zhou W. (2008). Monitoring calcium concentration in neurons with Cameleon. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105, 106–109 10.1263/jbb.105.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looger L. L., Griesbeck O. (2011). Genetically encoded neural activity indicators. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22, 18–23 10.1016/j.conb.2011.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.-Y., Wang L.-J., Muramatsu S.-I., Ikeguchi K., Fujimoto K.-I., Okada T., Mizukami H., Matsushita T., Hanazono Y., Kume A., Nagatsu T., Ozawa K., Nakano I. (2003). Intramuscular injection of AAV-GDNF results in sustained expression of transgenic GDNF, and its delivery to spinal motoneurons by retrograde transport. Neurosci. Res. 45, 33–40 10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00195-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundby A., Akemann W., Knöpfel T. (2010). Biophysical characterization of the fluorescent protein voltage probe VSFP2.3 based on the voltage-sensing domain of Ci-VSP. Eur. Biophys. J. 39, 1625–1635 10.1007/s00249-010-0620-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank M., Santos A. F., Direnberger S., Mrsic-Flogel T. D., Hofer S. B., Stein V., Hendel T., Reiff D. F., Levelt C., Borst A., Bonhoeffer T., Hubener M., Griesbeck O. (2008). A genetically encoded calcium indicator for chronic in vivo two-photon imaging. Nat. Methods 5, 805–811 10.1038/nmeth.1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshel J. H., Mori T., Nielsen K. J., Callaway E. M. (2010). Targeting single neuronal networks for gene expression and cell labeling in vivo. Neuron 67, 562–574 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Martindale J., Berwick J., Mayhew J. (2006). Investigating neural–hemodynamic coupling and the hemodynamic response function in the awake rat. Neuroimage 32, 33–48 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli A. E., Larregina A. T., Smith-Arica J., Dewey R. A., Southgate T. D., Ambar B., Fontana A., Castro M. G., Lowenstein P. R. (1999). Neuronal and glial cell type-specific promoters within adenovirus recombinants restrict the expression of the apoptosis-inducing molecule Fas ligand to predetermined brain cell types, and abolish peripheral liver toxicity. J. Gen. Virol. 80, 571–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrsic-Flogel T. D., Hofer S. B., Ohki K., Reid R. C., Bonhoeffer T., Hubener M. (2007). Homeostatic regulation of eye-specific responses in visual cortex during ocular dominance plasticity. Neuron 54, 961–972 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y., Iwasaki H., Sasaki M., Inaba K., Okamura Y. (2005). Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature 435, 1239–1243 10.1038/nature03650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh H., Perron A., Akemann W., Iwamoto Y., Knöpfel T. (2011). Optogenetic monitoring of membrane potentials. Exp. Physiol. 96, 13–18 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.053942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargi-Aizenman J. L., Griffin D. E. (2001). Sindbis virus-induced neuronal death is both necrotic and apoptotic and is ameliorated byn-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists. J. Virol. 75, 7114–7121 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7114-7121.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson J. L., Jappelli R., Scheeff E. D., Manning G., Obata K., Brenner S., Callaway E. M. (2009a). Short promoters in viral vectors drive selective expression in mammalian inhibitory neurons, but do not restrict activity to specific inhibitory cell-types. Front. Neural Circuits 5:12 10.3389/neuro.04.019.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson J. L., Yanagawa Y., Obata K., Callaway E. M. (2009b). Preferential labeling of inhibitory and excitatory cortical neurons by endogenous tropism of adeno-associated virus and lentivirus vectors. Neuroscience 161, 441–450 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q.-T., Tsai P. S., Kleinfeld D. (2006). MPScope: a versatile software suite for multiphoton microscopy. J. Neurosci. Methods 156, 351–359 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niell C. M., Stryker M. P. (2008). Highly selective receptive fields in mouse visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 28, 7520–7536 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0623-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K., Chung S., Ch'ng Y. H., Kara P., Reid R. C. (2005). Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature 433, 597–603 10.1038/nature03274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron A., Mutoh H., Akemann W., Gautam S. G., Dimitrov D., Iwamoto Y., Knöpfel T. (2009a). Second and third generation voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins for monitoring membrane potential. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2:5 10.3389/neuro.02.005.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron A., Mutoh H., Launey T., Knöpfel T. (2009b). Red-shifted voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins. Chem. Biol. 16, 1268–1277 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiff D. F., Ihring A., Guerrero G., Isacoff E. Y., Joesch M., Nakai J., Borst A. (2005). In vivo performance of genetically encoded indicators of neural activity in flies. J. Neurosci. 25, 4766–4778 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4900-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M., Tsaur M. L., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1994). Contrasting subcellular localization of the Kv1.2 K+ channel subunit in different neurons of rat brain. J. Neurosci. 14, 2408–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M. S., Isacoff E. Y. (1997). A genetically encoded optical probe of membrane voltage. Neuron 19, 735–741 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80955-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. M., Ahrens K. F., Lee H., Dean C. B., Isacoff E. Y. (2007). “In vivo intrinsic and stimulus induced modulation of rat visual cortex neurons assessed with a genetically encoded fluorescent voltage sensor and two-photon imaging,” in Program No. 451.1 2007 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, (San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience; ). [Online]. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. M., Raffi M., Phinney R. E., Turner J. A., Jando G. (2003). Functional architecture of eye position gain fields in visual association cortex of behaving monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 1279–1294 10.1152/jn.01179.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons S. B., Chiu J., Favorov O. V., Whitsel B. L., Tommerdahl M. (2007). Duration-dependent response of si to vibrotactile stimulation in squirrel monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 2121–2129 10.1152/jn.00513.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovin H., Arieli A., Hildesheim R., Grinvald A. (2002). Long-term voltage-sensitive dye imaging reveals cortical dynamics in behaving monkeys. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 3421–3438 10.1152/jn.00194.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohya K., Kameyama K., Yanagawa Y., Obata K., Tsumoto T. (2007). GABAergic neurons are less selective to stimulus orientation than excitatory neurons in layer II/III of visual cortex, as revealed by in vivo functional Ca2+ imaging in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 27, 2145–2149 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4641-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stosiek C., Garaschuk O., Holthoff K., Konnerth A. (2003). In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7319–7324 10.1073/pnas.1232232100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Sasaki T., Usami A., Matsuki N., Ikegaya Y. (2007). Watching neuronal circuit dynamics through functional multineuron calcium imaging (fMCI). Neurosci. Res. 58, 219–225 10.1016/j.neures.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans J.-M., Vandenberghe L. H., Haute C. V. D., Thiry I., Deroose C. M., Mortelmans L., Wilson J. M., Debyser Z., Baekelandt V. (2007). Comparative analysis of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 in mouse brain. Hum. Gene Ther. 18, 195–206 10.1089/hum.2006.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Hires S. A., Mao T., Huber D., Chiappe M. E., Chalasani S. H., Petreanu L., Akerboom J., Mckinney S. A., Schreiter E. R., Bargmann C. I., Jayaraman V., Svoboda K., Looger L. L. (2009). Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods 6, 875–881 10.1038/nmeth.1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P. S., Nishimura N., Yoder E. J., While A., Dolnick E., Kleinfeld D. (2002). “Principles, design and construction of a two-photon scanning microscope for in vivo and in vitro studies,” in Methods for In Vivo Optical Imaging, ed. Frostig R. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ), 113–171 [Google Scholar]

- Walikonis R. S., Jensen O. N., Mann M., Provance D. W., Mercer J. A., Kennedy M. B. (2000). Identification of proteins in the postsynaptic density fraction by mass spectrometry. J. Neurosci. 20, 4069–4080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Nagai M., Okamura J. (2011). Orientation dependency of intrinsic optical signal dynamics in cat area 18. Neuroimage 57, 1140–1153 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickersham I. R., Lyon D. C., Barnard R. J. O., Mori T., Finke S., Conzelmann K.-K., Young J. A. T., Callaway E. M. (2007). Monosynaptic restriction of transsynaptic tracing from single, genetically targeted neurons. Neuron 53, 639–647 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Asokan A., Samulski R. J. (2006). Adeno-associated virus serotypes: vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 14, 316–327 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Li J., Samulski R. J. (1998). Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J. Virol. 72, 2224–2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Callaway E. M. (2009). Laminar specificity of functional input to distinct types of inhibitory cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 70–85 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4104-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Roby K. D., Callaway E. M. (2006). Mouse cortical inhibitory neuron type that coexpresses somatostatin and calretinin. J. Comp. Neurol. 499, 144–160 10.1002/cne.21101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Y., Klistorner A., Thie J., Graham S. (2011). Improving reproducibility of VEP recording in rats: electrodes, stimulus source and peak analysis. Doc. Ophthalmol. 123, 109–119 10.1007/s10633-011-9288-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Watanabe I., Gomez B., Thornhill W. B. (2003). Heteromeric Kv1 potassium channel expression: amino acid determinants involved in processing and trafficking to the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25558–25567 10.1074/jbc.M207984200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]