Abstract

We report a novel activatable NIR fluorescent probe for in vivo detection of cancer-related matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity. The probe is based on a triple-helical peptide substrate (THP) with high specificity for MMP-2 and MMP-9 relative to other members of the MMP family. MMP-2 and MMP-9 (also known as gelatinases) are specifically associated with cancer cell invasion and cancer-related angiogenesis. At the center of each 5 kDa peptide strand is a gelatinase sensitive sequence flanked by 2 Lys residues conjugated with NIR fluorescent dyes. Upon self-assembly of the triple-helical structure, the 3 peptide chains intertwine, bringing the fluorophores into close proximity and reducing fluorescence via quenching. Upon enzymatic cleavage of the triple-helical peptide, 6 labeled peptide chains are released, resulting in an amplified fluorescent signal. The fluorescence yield of the probe increases 3.8-fold upon activation. Kinetic analysis showed a rate of LS276-THP hydrolysis by MMP-2 (kcat/KM = 30,000 s−1M−1) similar to that of MMP-2 catalysis of an analogous fluorogenic THP. Administration of LS276-THP to mice bearing a human fibrosarcoma xenografted tumor resulted in a tumor fluorescence signal more than 5-fold greater than muscle. This signal enhancement was reduced by treatment with the MMP inhibitor Ilomostat, indicating that the observed tumor fluorescence was indeed enzyme mediated. These results are the first to demonstrate that triple-helical peptides are suitable for highly specific in vivo detection of tumor-related MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity.

Introduction

MMPs are a family of zinc dependent proteases capable of degrading extracellular matrix (ECM) components and other extracellular proteins. MMPs are synthesized as inactive zymogens (proMMPs) and are either secreted into the extracellular space or anchored to the cell membrane. Activation requires removal of the propeptide domain by proteolysis to expose the active site within the catalytic domain (1).

A number of MMPs are overexpressed in various human cancers. Among these are MMP-2 (gelatinase A, 72 kDa gelatinase, or 72 kDa type IV collagenase) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B, 92 kDa gelatinase, or 92 kDa type IV collagenase), both referred to collectively as gelatinases. MMP-2 and MMP-9 are secreted as zymogens usually by stromal cells such as fibroblasts (2, 3). Cancer types that have shown increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 include breast (4, 5), colorectal (6, 7), prostate (8, 9), and gastric cancer (10, 11). MMP-2 overexpression is strongly linked to melanoma progression whereas relatively little MMP-2 expression is observed in normal tissues of the skin (12). These tissues are highlighted because they are accessible to the penetration depth of NIR light or are accessible with endoscopes fitted with NIR reflectance imaging sensors (13).

Gelatinases are important imaging targets due to their possible prognostic capability. For example, increased MMP-2 expression predicts decreased disease free survival in human prostate cancer (14). Additionally, MMP-2 in breast carcinoma correlated with shortened recurrence-free survival and relative overall survival (15). Therefore, the development of specific gelatinase imaging probes would be of great interest in unraveling their role in tumor biology in animal models or diagnosing, directing, or monitoring therapy in humans. Imaging probes have been reported for detecting MMPs with nuclear imaging (either PET or SPECT), optical imaging, and magnetic resonance imaging [reviewed in (16)]. At present, peptide substrates for gelatinase activity, while efficiently hydrolyzed by MMP-2, are relatively promiscuous and are subject to hydrolysis by other members of the MMP family (17-19). An understanding of molecular events, such as enzyme activity, requires high specificity of the quenched probe for the substrate. The current lack of specificity of peptide-based substrates is hindering imaging of gelatinase activity in vivo and is thus limiting an understanding of how gelatinases could serve as markers for cancer progression or for monitoring the severity of other diseases (20, 21).

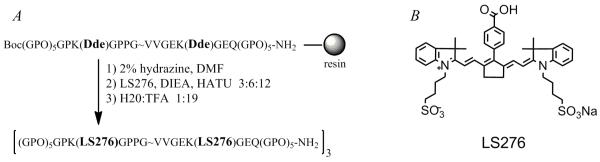

For this reason, a triple-helical peptide (THP) that is highly specific for MMP-2 and MMP-9 has been chosen for NIRF imaging. The self-assembling THP incorporates a native collagen sequence (residues 437-447) from the α1 chain of type V collagen (22, 23). This natural collagen sequence, modified to contain a pair of Lys residues flanking the hydrolysis site, contains at both the N- and C-termini repeating Gly-Pro-4-hydroxy-l-proline (GPO) triplets that result in self-assembly of three single-stranded peptides into one triple-helical peptide. The support for triple-helicity is evident in the strong molar ellipticity at λ = 225 nm which diminishes upon thermal denaturation of the helix. The type V collagen sequence GPPG~VVGEKGEQ (the scissile bond lies between G and V), as a single-stranded peptide (i.e., without the GPO triplets), was hydrolyzed extremely slowly by either MMP-2 or MMP-9 (24). Therefore, it is the triple-helical structural feature, along with the sequence, that imparts the substrate specificity amongst the various MMPs (24). We hypothesized that the THP backbone would serve as the core of a quenched fluorescent probe for detection of MMP activity in cancer and other diseases. We have constructed an activatable molecular probe by covalently conjugating NIR fluorescent dyes (LS276) to ε-amino groups of Lys that flank the hydrolysis site (Figure 1 A). LS276 is a highly fluorescent, mono-functional, water-soluble heptamethine cyanine dye (Figure 1 B) (25). The close proximity of dyes renders them relatively non-fluorescent. The single-stranded peptides were synthesized entirely on the solid phase and LS276 was incorporated while the peptide was resin-bound. After cleavage from the resin, the resulting triple-helical peptide, LS276-THP, was evaluated in vitro to determine whether the addition of the fluorophores impeded the formation of the triple-helix resulting in detrimental increases of the KM value to MMP-2. Additionally, LS276-THP was tested in vivo for its ability to visualize gelatinase activity in a tumor bearing animal model.

Figure 1.

A) Solid-phase synthesis of LS276-THP (“O” represents 4-hydroxy-l-proline). B) Chemical structure of LS276.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Ilomastat was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). MMPSense™ 680 was purchased from VisEn Medical (Bedford, MA) and prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Synthesis

The THP was synthesized as previously described (Figure 1) (22). After removal of the 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohexylidene)ethyl (Dde) protecting groups (2% hydrazine, DMF), rinsing (3 × 5 mL DMF, 10% aqueous DMF, CH2Cl2, CH3OH), and drying (in vacuo), LS276 was conjugated to the ε-amino groups of Lys (25 mg resin, resin:LS276:DIEA:HATU 1:6:24:12) in DMF. After reaction (3.5 h), the mixture was filtered and rinsed (3 × 5 mL DMF, CH2Cl2, CH3OH). The Kaiser test was negative indicating complete coupling of LS276. The peptide was cleaved from the resin (water:TFA 1:19, 3 h), diluted with water, and lyophilized. The crude mixture was re-dissolved (0.0001% ammonia, pH 8) and purified by size exclusion gel chromatography (G-25). Substitution levels were determined by absorption (λ = 780 nm, ε = 220,000 cm−1 M−1) and the ninhydrin method utilizing bovine insulin as a standard (25, 26). The molecular weight was confirmed by ESI-TOF-MS (Figure S1).

Quenching

To determine the amount of quenching, the fluorescence of unhydrolyzed LS276-THP (fintact) was compared with the fluorescence of completely hydrolyzed LS276-THP (fhydrolyzed), utilizing [(fhydrolyzed-fintact)/fhydrolyzed] × 100 = % quenched. Three concentrations of LS276-THP (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 μM, n=3 per concentration) were digested with MMP-2 (20 nM) until fluorescence reached a plateau with no further increases (3.75 h).

Enzyme assays

The proenzyme of MMP-2 was activated using 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA). APMA (10 mM, 3.5 mg/mL) in assay buffer (50 mM tricine pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35) was diluted to 2 mM prior to addition to the proenzyme solution. ProMMP-2 was activated by adding APMA (2 mM) to a proMMP-2 solution in equal parts by volume for a final solution of 1 mM (1 h, 37°C) of each component. Enzyme kinetics were carried out using activated MMP-2 at nominal concentrations of 5 nM at 37°C. The rates of hydrolysis were determined by liberated fluorescence units in a microtiter plate reader (λexcitation = 780 nm, λemission = 810 nm). The relative fluorescent units were converted to molar units utilizing LS276 as an external standard (25). The error values are standard error of the mean. The amount of active enzyme (ET) was taken from published values of the % active enzyme generated under identical conditions (70%, MMP-2) (27, 28). KM values were determined by non-linear regression utilizing Vo = VMAX[S]/(KM +[S]) (GraphPad Prism version 5.04 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and kcat was determined from ET and VMAX.

Immunohistochemistry

Ten μm thick sections were cut from tumor tissue snap-frozen in OCT media for routine staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and IHC staining with MMP-9 and MMP-2. The polyclonal antibodies used were Anti-mouse MMP-9 (5 μg/ml) and Anti-mouse/rat MMP-2 (5 μg/ml) from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Immunohistochemical analysis staining was done with the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The reaction products were visualized using diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as a chromogen. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. As negative controls, primary antibody was replaced with 1X PBS.

In vivo imaging

For imaging studies, human fibrosarcoma xenografts were grown by subcutaneous injection of 200,000 HT1080 cells (ATCC) in the flanks of 6-week old male NCR nude mice (Taconic Farms, Hudson, NY). Tumor-bearing mice received 1 mg/kg LS276-THP probe i.p. (20 nmol in 250 μL PBS) (n=4). A second group (n=3) was treated with Ilomastat (1 mg/kg in DMSO i.p) 2 h before LS276-THP injection and again 4 and 20 h after injection. A third group (n=3) received 2 nmol MMPSense™ 680 i.v. Mice in the LS276-THP groups were imaged using the Kodak IS4000MM multimodal imaging system (Carestream Health, New Haven, CT) immediately and at 1, 4, and 24 h after LS276-THP injection, followed by ex vivo fluorescence biodistribution imaging of organ tissues. Fluorescence images were acquired using λexcitation = 755 ± 35 nm and λemission = 830 ± 75 nm detection, 60 sec exposure with 2×2 binning. Mice in the MMPSense™ 680 group were imaged with the Pearl NIR fluorescence imaging system (LiCor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) with λexcitation = 685 nm and λemission = 720 nm collection. Region of interest (ROI) analysis was performed using ImageJ software (LS276-THP groups) or Pearl Cam Software (MMPSense™ 680). Mean fluorescence intensity values for tumor and contralateral flank ROIs were plotted versus time to analyze biodistribution and activation kinetics. Fluorescence values for ex vivo tissues were normalized to equalize blood fluorescence levels due to differences in absolute values between imaging systems and detection wavelengths. Statistical significance was calculated with a one-tailed, unpaired t-test (GraphPad Prism version 5.04 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Outlying data were analyzed with the Grubb’s test. All animal studies were conducted by protocols approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Probe development and characterization

Near infrared fluorescent THP probes were synthesized for specific detection of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity in vivo. We hypothesized that full substitution of the two Lys ε–amino groups per peptide strand would result in high efficiency quenching of fluorescence upon self-assembly of the triple-stranded peptide structure. Fluorescence would then be regenerated by gelatinase catalyzed hydrolysis, reporting MMP-2/-9 activity in aggressive tumors.

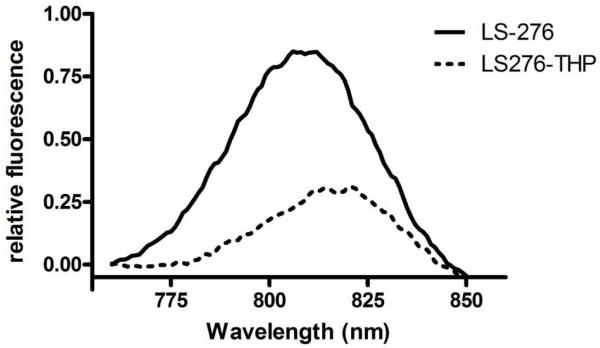

Currently, carbocyanine analogs, especially indocyanine green (ICG), are widely used as optical reporters for in vivo imaging of tumors because of their established safety profile in humans and known photo-physical properties (29, 30). The carbocyanine dyes absorb and emit light in the NIR and therefore are suitable for imaging superficial or even deep-tissue disease states. Because our ultimate goal is to develop enzyme activatable probes for preclinical drug testing and diagnostic use in humans, we have utilized the NIR dye LS276. LS276 is compatible with relatively harsh basic conditions of solid-phase peptide synthesis and incorporates a single carboxylic acid group for conjugation to amino groups of resin-bound peptides (25). Mass spectrometric analysis of the purified LS276-THP indicated di-substituted single-stranded peptide: calculated (M+H)+ = 5666, observed (M+H)+ = 5667 (Figure S1), which was corroborated by ninhydrin analysis that showed a substitution level of 6 LS276: 1 THP indicating complete conjugation of LS276 to the ε–amino groups of Lys while the peptide was resin-bound. The emission spectrum of LS276-THP shifted slightly to the red by ~6 nm relative to unconjugated LS276, but otherwise the spectral properties of LS276-THP were unchanged indicating stability during peptide synthesis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence spectra of LS276 (solid) and LS276-THP (dashed), where λexcitation = 780 nm and λemission = 760-850 nm.

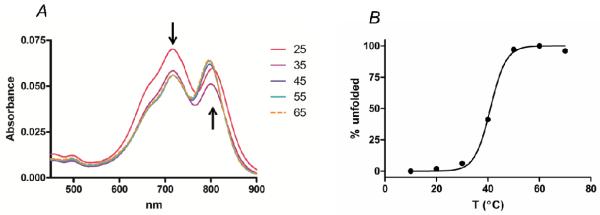

By comparing the fluorescence of a fully proteolyzed sample of LS276-THP with an undigested sample, an average value of quenching of 73.5% ± 0.5% (standard deviation) of LS276 fluorescence was observed in the THP. By comparison, more flexible single-stranded peptides, such as the MMP-7 substrate GVPLSLTMGC bearing a heterologous donor and acceptor pair of near infrared dyes on the N- and C-terminus, yielded a level of 85% quenching with an approximate 7-fold increase after digestion with MMP-7 (31). In flexible peptides, a mechanism of quenching has been attributed to the formation of intramolecular dimers between the donor and quencher fluorophores (32). Examination of the absorption profile of LS276-THP under conditions too dilute for intermolecular aggregation (33 nM) provided evidence of H-aggregation by the absorption at λ = 715 nm relative to the absorption of the non-aggregated dye (λ = 815 nm) (Figure 3 A) (33, 34). Furthermore, as the triple-helix started to unwind during melting, the absorption band due to H-aggregation decreased while that of the non-aggregated dye increased (Figure 3 B). This indicated that quenching, at least in part, was due to sandwich-style stacking of the fluorophores. The triple-helical backbone is somewhat rigid, limiting the possibility of intramolecular collisional quenching. The level of quenching determined for the LS276-THP is lower than that reported for other NIR fluorogenic probes that have been used in vivo (26, 35, 36); however, these molecular probes were based on short peptide sequences that have lower selectivity for MMP-2/-9. Moreover, achieving visualization of protease activity in vivo relies on a complex interplay of factors including extravasation of the probe into the tumor, enzyme-mediated proteolysis, and retention of the proteolyzed fragments within the tumor.

Figure 3.

A) Absorbance of LS276-THP with varying temperature. B) Thermal transition curve for LS276-THP.

Plotting the change in absorbance of the LS276-THP at λ = 815 nm as a function of temperature yielded a sigmoidal plot with a midpoint transition temperature of 41°C (TM=41°C) (Figure 3 B). While determining the melting temperature in this fashion does not take into account the conformational state of the triple-helical backbone, this value compares well with that previously determined for the fluorogenic THP [(GPO)5GPK((7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl)GPPG~VVGEK(2,4-dinitrophenyl)GEQ(GPO)5]3 (TM=45°C) (24), showing that there was no destabilization of the triple-helix upon incorporation of LS276.

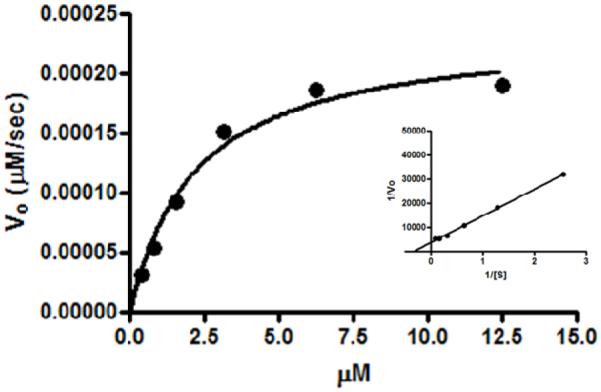

Kinetics of proteolysis

To determine whether the addition of the fluorophores perturbed the triple-helix and altered substrate avidity for the gelatinases, enzyme kinetic parameters were determined (Figure 4). LS276-THP was efficiently hydrolyzed by MMP-2 (KM = 2.2 ± 0.24 μM, kcat = 0.066 s−1, kcat/KM = 30,000 s−1M−1). The kinetic constants and catalytic rate were of similar magnitude to those observed for MMP-2 hydrolysis of a fluorogenic THP with the sequence of [(GPO)5GPK((7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl)GPPG~VVGEK(2,4-dinitrophenyl)GEQ(GPO)5]3 (KM = 4.4 μM, kcat = 0.062 s−1, kcat/KM = 14,000 s−1M−1) (24). The comparable kinetic constants indicate that LS276 incorporation was not detrimental to efficient MMP-2 hydrolysis (37). This result suggests that the THP could accommodate a variety of near infrared dyes with differing sizes and chemical properties (such as varying hydrophobicity or ionizable functional groups). A prior study examining MMP-2 hydrolysis of fluorogenic THPs possessing methoxycoumarin analogs reached a similar conclusion(38).

Figure 4.

Proteolysis of increasing concentrations of LS276-THP by MMP-2. Lineweaver-Burk analysis is provided in the inset. Error bars indicating standard deviation are too narrow to be visualized on this plot.

The kcat/KM value provides an important criterion in the evaluation of a substrate with quenched fluorophores for molecular imaging. Those substrates with the highest kcat/KM values would be expected to be the most rapidly hydrolyzed before wash-out from the target site, resulting in greater signal to noise. In vivo protease imaging is in a nascent stage but the feasibility of these studies in small animals has been reported. For example, MMP-2 activity in mouse models was visualized with a poly-lysine-PEG co-polymer, of relatively high molecular weight (450 kDa), when conjugated to a peptide with a sequence of -Pro-Leu-Gly~Val-Arg-Gly-(35, 39). This peptide itself was a substrate for MMP-2 (kcat = 4.1 sec−1 and KM = 290 μM, kcat/KM = 1.4 × 104 M−1s−1) (19). Presumably, conjugation to the polymer did not change these kinetic parameters. In another study, a fluorescein-linear peptide bearing a MMP-7 hydrolysis site and tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) were conjugated to a polyamido-amino dendrimeric polymer (14 kDa) (26). Fluorescein was the FRET donor and TMR the acceptor. The dendrimeric peptide was efficiently (kcat/KM = 1.9 × 105 M−1 s−1) and selectively (MMP-2 kcat/KM = 3.4 × 103 M−1 s−1, MMP-3 kcat/KM = 1.5 × 104 M−1 s−1) cleaved by the target, MMP-7. While the endogenous fluorescence was competing with fluorescein fluorescence, a subcutaneous tumor (MMP-7 positive) was visualized relative to a control (MMP-7 negative). An additional example was in vivo tumor imaging with a polymeric quenched-fluorescent probe activated by cathepsin D (40). The peptide substrate bearing the Cy5.5 quenched probes had a relatively high efficiency for cathepsin D mediated hydrolysis (kcat/KM = 7 × 106 M−1 s−1). Together, these examples suggest that there is a range of kcat/KM values of ~1 × 104 to 7 × 106 M−1 s−1 for substrates that successfully imaged in vivo proteolytic activity (35, 39, 40). The kcat/KM value for LS276-THP hydrolysis by MMP-2 falls inside this range and, due to its kinetic parameters, it is suitable for in vivo imaging of gelatinase activity.

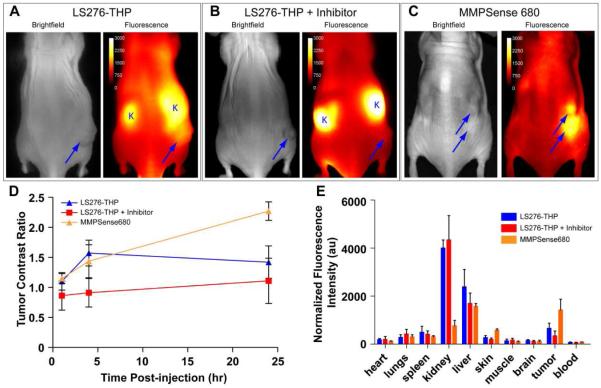

In vivo Imaging of MMP activity with LS276-THP and MMPSense™ 680

Planar fluorescence imaging was performed in mice bearing HT1080 sub cutaneous xenografts after contrast agent injection. The HT1080 human fibrosarcoma is well known for its high expression of gelatinases (18, 41, 42). Intravenous administration of LS276-THP resulted in rapid clearance of the conjugate with no observable visualization of gelatinase activity in the tumor (data not shown). Unlike large molecular weight polymers, such as MMPSenseTM 680, LS276-THP is below the renal filtration threshold leading to fast clearance via the kidneys. Intravenous administration resulted in low tumor-specific contrast, likely due to rapid washout of the relatively small probe (~15 kDa, data not shown). To slow the uptake and clearance of LS276-THP and maintain a steady concentration of the gelatinase sensing probe in blood, it was administered intraperitoneally.

Planar fluorescence imaging after injection of the LS276-THP probe demonstrated low initial fluorescence intensity followed by high peak fluorescence at 4 h post-injection and cleared from most tissues after 24 h (Figure 5). While tumor fluorescence was partially obscured by overwhelming signal from the ipsilateral kidney, the fluorescence intensity from the tumor region was higher than that of the contralateral flank at 4 and 24 h. This rapid increase in fluorescence intensity was not observed in mice treated with Ilomastat, a pan MMP inhibitor. Ilomastat is a potent inhibitor of gelatinase activity (Ki = 0.5 nM, MMP-2, Ki = 0.2 nM, MMP-9) (43). Instead, a steady increase in fluorescence intensity occurred, indicating incomplete inhibition of tumor-associated MMP-2/MMP-9 activity. The fluorescence intensities in the tumor region relative to contralateral thigh shows that LS276-THP had maximum contrast at 4 h relative to mice receiving LS276-THP and inhibitor (Figure 5 A and B). Normalized fluorescence biodistribution measured from ex vivo tissues confirmed higher tumor accumulation for LS276-THP relative to LS276-THP in Ilomastat-treated controls (Figure 5 E). The ex vivo tumor-to-muscle ratio of fluorescence was 5.36 ± 2.32 for LS276-THP versus 1.99 ± 0.42 for LS276-THP + inhibitor (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Representative in vivo whole-body images of mice bearing HT1080 tumor xenografts 24 h after injection of (A) LS276-THP; n=4, (B) LS276-THP and inhibitor; n=3, or (C) MMPSense™ 680; n=3. Tumors (arrows) and kidney (K) regions are marked. (D) The ratio of tumor and contralateral thigh ROI fluorescence with respect to time show the time dependent activation of the molecular probes. (E) Ex vivo fluorescence biodistribution confirmed the high fluorescence in the non-inhibited tumors and the high retention of LS276-THP in the mouse kidneys relative to the larger MMPSense™ 680. Error bars represent standard deviation; au = arbitrary units.

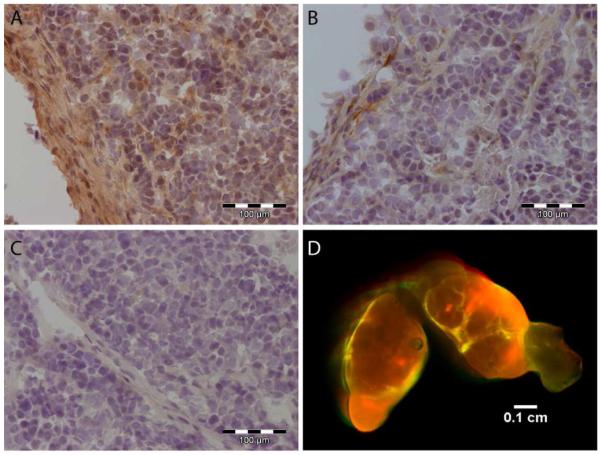

Because planar imaging is surface weighted, the relatively high fluorescence from the skin obscured fluorescence signal from the tumor. To obtain a better understanding of whether the observed tumoral fluorescence was mediated by enzyme hydrolysis, an ex vivo fluorescence imaging biodistribution was performed. High fluorescence intensity was observed from the liver and kidneys, indicating a mixed clearance pathway for the probe and possibly for the hydrolyzed fragments (Figure 5). Fluorescence was also observed in non-target tissues including lungs, spleen, and skin that was not reduced with the inhibitor (P > 0.05). On the other hand, the tumor mediated accumulation was reduced by the inhibitor Ilomastat (P < 0.05). While Ilomastat is a pan-MMP inhibitor, the THP sequence used in this work has already been shown to be impervious to the proteolysis of other tumor specific MMPs such as MMP-1, MMP-13, and MMP-14. Other tumor MMPs that are activated in cancer such as MMP-7 need not have been investigated because they do not proteolyze collagen in the α1(V)436-447 region (24). Additionally, examination of the dissected HT1080 tumors by immunohistochemistry and fluorescence imaging showed strong expression at the tumor periphery, consistent with previous observations of gelatinase expression (Figure 6) (44, 45). The correlation of intense fluorescence and as well as intense staining at the tumor periphery co-localizes gelatinase expression with NIR fluorescence and supports the conclusion of gelatinase mediated proteolysis of LS276-THP. Taken together, these results strongly support MMP-2 mediated activation of LS276-THP.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry for MMP-2 (A), MMP-9 (B), and secondary antibody control (C) with hematoxylin counterstain in HT1080 xenograft cryosections. (D) Fluorescence imaging of HT1080 tumor xenograft 24 h after injection of the LS276-THP probe.

To place these results in perspective, the tumor associated fluorescence of MMPSense™ 680 was investigated in the same tumor model. This is a commercially available pan-matrix metalloproteinase imaging agent that has been utilized in a variety of animal models to investigate MMP activity as a function of disease (20, 21). MMPSense™ 680 has molecular weight of 450 kDa and consists of relatively short peptides bearing fluorophores conjugated to a polymer backbone. Within the peptide is an MMP sensitive sequence. The close proximity of the fluorophores results in quenching of the fluorescence. Fluorescence dequenching is observed after enzyme mediated hydrolysis as the peptide fragments bearing the fluorophores are liberated from the polymer. The molecular weight of MMPSense™ 680 is relatively large; therefore it was administered intravenously rather than impose the additional barrier of peritoneal absorption with i.p. administration.

The tumor-specific fluorescence contrast with MMPSense™ 680 increased over time for 24 h, indicating that the higher molecular weight resulted in greater residence time in the tumor tissue and therefore greater activation. By 24 h post-injection, the tumor contrast for MMPSense™ 680 was about two-fold higher than the contralateral thigh while the contrast ratio for LS276-THP remained at about 1.5, unchanged from the 4 h time point. Another factor that could have contributed to the higher tumoral activation of MMPSense™ 680 was the lack of MMP selectivity. The peptide bearing the quenched fluorophores that is conjugated to the polymeric backbone of MMPSense™ 680 contains the sequence -PLGVR-which is subject to proteolysis by members of the MMP family that include, in addition to the gelatinases, MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-7 (35, 46, 47). These MMPS are included in those that have been shown to be expressed by the human fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080 (48) but are not always associated with tumor invasiveness or aggressive phenotypes (11, 14, 15, 49, 50). In fact, the correlation of MMP-2/-9 activity with tumor aggressiveness is a driving force in the development of new inhibitors (51-53). These contrasting results indicate that both increased tumor residence time and increased quenching efficiency are needed to improve the contrast enhancement due to MMP-2 activation in triple-helical peptides. While the tumor-specific fluorescence enhancement is slightly higher with MMPSense™ 680 relative to that of LS276-THP in this study, the utilization of triple-helical peptides represents a leap forward in selectively visualizing gelatinase activity by replication of the natural enzyme substrate.

Conclusions

Overall, we have presented the synthesis and characterization of a THP bearing NIR dyes with a relatively high degree of quenching. This probe, LS276-THP, retained the kinetic parameters of the previously described fluorogenic THP and was efficiently hydrolyzed by MMP-2. LS276-THP enabled the visualization of MMP-2 activity in mice bearing human tumors which was diminished with a known inhibitor. This work represents the first report of the use of a THP for in vivo imaging of proteolytic activity. Work is in progress to increase the quenching levels and serum half-life to affect greater in vivo contrast enhancement for sensing tumor-related MMP-2 activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R21 CA CA131660-02 and 3R21CA131660-02S1 (Edwards), R01CA098799 (Fields) from the National Cancer Institute and K01RR026095 (Akers) from the National Center for Research Resources. Mass spectrometry was provided by the Washington University Mass Spectrometry Resource, an NIH Research Resource (P41RR0954).

Footnotes

Supporting information available: ES-MS of LS276-THP. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Pacheco MM, Mourao M, Mantovani EB, Nishimoto IN, Brentani MM. Expression of gelatinases A and B, stromelysin-3 and matrilysin genes in breast carcinomas: clinico-pathological correlations. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16:577–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1006580415796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Remacle AG, Noel A, Duggan C, McDermott E, O’Higgins N, Foidart JM, Duffy MJ. Assay of matrix metalloproteinases types 1, 2, 3 and 9 in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:926–31. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Baker EA, Bergin FG, Leaper DJ. Matrix metalloproteinases, their tissue inhibitors and colorectal cancer staging. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1215–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Baker EA, Leaper DJ. Measuring gelatinase activity in colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:24–9. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kuniyasu H, Troncoso P, Johnston D, Bucana CD, Tahara E, Fidler IJ, Pettaway CA. Relative expression of type IV collagenase, E-cadherin, and vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor in prostatectomy specimens distinguishes organ-confined from pathologically advanced prostate cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2295–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Upadhyay J, Shekarriz B, Nemeth JA, Dong Z, Cummings GD, Fridman R, Sakr W, Grignon DJ, Cher ML. Membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) and MMP-2 immunolocalization in human prostate: change in cellular localization associated with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Nomura H, Fujimoto N, Seiki M, Mai M, Okada Y. Enhanced production of matrix metalloproteinases and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (gelatinase A) in human gastric carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:9–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960220)69:1<9::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Sier CF, Kubben FJ, Ganesh S, Heerding MM, Griffioen G, Hanemaaijer R, van Krieken JH, Lamers CB, Verspaget HW. Tissue levels of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 are related to the overall survival of patients with gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:413–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hofmann UB, Westphal JR, Zendman AJ, Becker JC, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GN. Expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and its co-localization with membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) correlate with melanoma progression. Journal of Pathology. 2000;191:245–56. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH632>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Piao D, Xie H, Zhang W, Krasinski JS, Zhang G, Dehghani H, Pogue BW. Endoscopic, rapid near-infrared optical tomography. Opt Lett. 2006;31:2876–8. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.002876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Trudel D, Fradet Y, Meyer F, Harel F, Tetu B. Significance of MMP-2 expression in prostate cancer: an immunohistochemical study. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Talvensaari-Mattila A, Paakko P, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) is associated with survival in breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1270–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Scherer RL, McIntyre JO, Matrisian LM. Imaging matrix metalloproteinases in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:679–90. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Aguilera TA, Olson ES, Timmers MM, Jiang T, Tsien RY. Systemic in vivo distribution of activatable cell penetrating peptides is superior to that of cell penetrating peptides. Integrative biology: quantitative biosciences from nano to macro. 2009;1:371–81. doi: 10.1039/b904878b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bremer C, Tung CH, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging of MMP expression and therapeutic MMP inhibition. Academic Radiology. 2002;9(Suppl 2):S314–5. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Seltzer JL, Akers KT, Weingarten H, Grant GA, McCourt DW, Eisen AZ. Cleavage specificity of human skin type IV collagenase (gelatinase). Identification of cleavage sites in type I gelatin, with confirmation using synthetic peptides. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20409–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kaijzel EL, van Heijningen PM, Wielopolski PA, Vermeij M, Koning GA, van Cappellen WA, Que I, Chan A, Dijkstra J, Ramnath NW, Hawinkels LJ, Bernsen MR, Lowik CW, Essers J. Multimodality imaging reveals a gradual increase in matrix metalloproteinase activity at aneurysmal lesions in live fibulin-4 mice. Circulation. Cardiovascular imaging. 2010;3:567–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.933093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Littlepage LE, Sternlicht MD, Rougier N, Phillips J, Gallo E, Yu Y, Williams K, Brenot A, Gordon JI, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases contribute distinct roles in neuroendocrine prostate carcinogenesis, metastasis, and angiogenesis progression. Cancer research. 2010;70:2224–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yu Y, Berndt P, Tirrell M, Fields GB. Self assembling amphiphiles for construction of protein molecular architecture. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:12515–12520. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Fields CG, Lovdahl CM, Miles AJ, Hagen VL, Fields GB. Solid-phase synthesis and stability of triple-helical peptides incorporating native collagen sequences. Biopolymers. 1993;33:1695–707. doi: 10.1002/bip.360331107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lauer-Fields JL, Sritharan T, Stack MS, Nagase H, Fields GB. Selective hydrolysis of triple-helical substrates by matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:18140–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lee H, Mason JC, Achilefu S. Heptamethine cyanine dyes with a robust C-C bond at the central position of the chromophore. J Org Chem. 2006;71:7862–5. doi: 10.1021/jo061284u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).McIntyre JO, Fingleton B, Wells KS, Piston DW, Lynch CC, Gautam S, Matrisian LM. Development of a novel fluorogenic proteolytic beacon for in vivo detection and imaging of tumour-associated matrix metalloproteinase-7 activity. Biochem J. 2004;377:617–28. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Okada Y, Morodomi T, Enghild JJ, Suzuki K, Yasui A, Nakanishi I, Salvesen G, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 from human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Purification and activation of the precursor and enzymic properties. Eur J Biochem. 1990;194:721–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Vempati P, Karagiannis ED, Popel AS. A biochemical model of matrix metalloproteinase 9 activation and inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37585–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hawrysz DJ, Sevick-Muraca EM. Developments toward diagnostic breast cancer imaging using near-infrared optical measurements and fluorescent contrast agents. Neoplasia. 2000;2:388–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tsilou E, Csaky K, Rubin BI, Gahl W, Kaiser-Kupfer M. Retinal visualization in an eye with corneal crystals using indocyanine green videoangiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:123–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Pham W, Choi Y, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Developing a peptide-based near-infrared molecular probe for protease sensing. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:1403–7. doi: 10.1021/bc049924s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Packard BZ, Toptygin DD, Komoriya A, Brand L. Profluorescent protease substrates: intramolecular dimers described by the exciton model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Almutairi A, Akers WJ, Berezin MY, Achilefu S, Frechet JM. Monitoring the biodegradation of dendritic near-infrared nanoprobes by in vivo fluorescence imaging. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2008;5:1103–10. doi: 10.1021/mp8000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Philip R, Penzkofer A, Baumler W, Szeimies RM, Abels C. Absorption and fluorescence spectroscopic investigation of indocyanine green. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology a-Chemistry. 1996;96:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bremer C, Tung CH, Weissleder R. In vivo molecular target assessment of matrix metalloproteinase inhibition. Nature Medicine. 2001;7:743–8. doi: 10.1038/89126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A., Jr. In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:375–8. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lauer-Fields JL, Nagase H, Fields GB. Use of Edman degradation sequence analysis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry in designing substrates for matrix metalloproteinases. J Chromatogr A. 2000;890:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lauer-Fields JL, Kele P, Sui G, Nagase H, Leblanc RM, Fields GB. Analysis of matrix metalloproteinase triple-helical peptidase activity with substrates incorporating fluorogenic L- or D-amino acids. Anal Biochem. 2003;321:105–15. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mahmood U, Weissleder R. Near-infrared optical imaging of proteases in cancer. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2003;2:489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bredow S, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of proteolytic enzyme activity using a novel molecular reporter. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4953–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Faust A, Waschkau B, Waldeck J, Holtke C, Breyholz HJ, Wagner S, Kopka K, Heindel W, Schafers M, Bremer C. Synthesis and evaluation of a novel fluorescent photoprobe for imaging matrix metalloproteinases. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1001–8. doi: 10.1021/bc700409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).van Duijnhoven SM, Robillard MS, Nicolay K, Grull H. Tumor targeting of MMP-2/9 activatable cell-penetrating imaging probes is caused by tumor-independent activation. J Nuclear Med. 2011;52:279–86. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Galardy RE, Cassabonne ME, Giese C, Gilbert JH, Lapierre F, Lopez H, Schaefer ME, Stack R, Sullivan M, Summers B, et al. Low molecular weight inhibitors in corneal ulceration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:315–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jones JL, Glynn P, Walker RA. Expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, their inhibitors, and the activator MT1-MMP in primary breast carcinomas. J Pathol. 1999;189:161–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199910)189:2<161::AID-PATH406>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Singer CF, Kronsteiner N, Marton E, Kubista M, Cullen KJ, Hirtenlehner K, Seifert M, Kubista E. MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in breast cancer-derived human fibroblasts is differentially regulated by stromal-epithelial interactions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;72:69–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1014918512569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Jones EF, Schooler J, Miller DC, Drake CR, Wahnishe H, Siddiqui S, Li X, Majumdar S. Characterization of Human Osteoarthritic Cartilage Using Optical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Molecular imaging and biology: MIB: the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0480-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Zhu L, Xie J, Swierczewska M, Zhang F, Quan Q, Ma Y, Fang X, Kim K, Lee S, Chen X. Real-time video imaging of protease expression in vivo. Theranostics. 2011;1:18–27. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Giambernardi TA, Grant AM, Taylor GP, Hay RJ, Maher VM, McCormick J, Klebe RJ. Overview of matrix metalloproteinase expression in cultured human cells. Matrix Biol. 1998;16:483–496. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Hofmann UB, Westphal JR, Van Muijen GN, Ruiter DJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in human melanoma. J Invest Dermatology. 2000;115:337–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Hofmann UB, Westphal JR, Waas ET, Becker JC, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GN. Coexpression of integrin alpha(v)beta3 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) coincides with MMP-2 activation: correlation with melanoma progression. J Invest Dermatology. 2000;115:625–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Nuti E, Casalini F, Santamaria S, Gabelloni P, Bendinelli S, Da Pozzo E, Costa B, Marinelli L, La Pietra V, Novellino E, Margarida Bernardo M, Fridman R, Da Settimo F, Martini C, Rossello A. Synthesis and biological evaluation in U87MG glioma cells of (ethynylthiophene)sulfonamido-based hydroxamates as matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:2617–2629. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Testero SA, Lee M, Staran RT, Espahbodi M, Llarrull LI, Toth M, Mobashery S, Chang M. Sulfonate-Containing Thiiranes as Selective Gelatinase Inhibitors. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2010;2:177–181. doi: 10.1021/ml100254e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Wang J, Medina C, Radomski MW, Gilmer JF. N-Substituted homopiperazine barbiturates as gelatinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:4985–4999. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.