Abstract

The final common pathway to death in all of us is an arrhythmia, yet we still know far too little about the contribution of conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias to the compromised states of the human fetus. At no other time in the human life cycle is the human being at more risk of unexplained and unexpected death than during the prenatal period. The risk of sudden death from 20 to 40 weeks gestation is 6 to 12 deaths/1000 fetuses/year. This is equal to, and in some ethnic groups HIGHER, than the risk of death in the adult population with known coronary artery disease over the same time frame (6 to 12 deaths/1000 patients/year). Because only a small percentage of the United States population is pregnant each year, because fetal demise is not often acknowledged through public displays such as funerals, and finally because fetal death is culturally accepted to a much greater extent than it should be, this critically important area of women’s healthcare has not had the technological advances that have been seen in adult cardiac intensive care and other areas of medicine. Fetal cardiac deaths may be preventable and the diseases that lead to these deaths are often treatable, especially if the sophistication of our modern ICU’s could somehow be translated to the prenatal monitoring arena.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) displays actual electrical events, whereas the echocardiogram provides secondary mechanical assessment of rhythm. While fetal echocardiography has been very important in advancing perinatal medicine, it is no substitute for technology which can provide direct and accurate measures of QRS width, QT interval, ST segments, and fetal rhythm. The uterine environment and the vernix caseosa insulate the fetal ECG signals, making advancement in biotechnology more difficult than at older ages. Over the next decade, new and combined biotechnologies for fetal rhythm recording promise to reduce fetal mortality from cardiac diseases and arrhythmias, and to provide much more sophisticated electrophysiologic monitoring for the compromised high risk human fetus. Abnormalities in rhythm presently represent about 20% of referrals by obstetricians for fetal cardiac evaluation, yet we predict many electrophysiologic conditions in the human fetus go completely unrecognized because the conduction system can be significantly abnormal even if the rhythm is stable and within the normal range. An accurate electrophysiologic diagnosis can have important implications for the family and the physician. This review article will outline recent advances in evaluating fetal electrophysiology, helping the perinatologist to better understand the nuances of fetal arrhythmias.

The article is divided into two sections. The first section will cover the diagnosis and treatment of the arrhythmias in the fetus. The second section will cover the diagnosis and treatment of the newborn infant with arrhythmias.

Fetal arrhythmias: diagnosis and management

Fetal arrhythmias are benign in most cases and occur in as many as 1% to 3% of all pregnancies [1,2]. Most of these arrhythmias are ectopic premature atrial contractions (PACs) detected by fetal auscultation between 18 weeks’ and term gestation. In approximately 10% of pregnancies complicated by fetal arrhythmias, the arrhythmia may be potentially life threatening. In those cases, the most likely diagnoses for tachyarrhythmias (heart rate in excess of 180 beats/min) are supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and atrial flutter; for bradyarrhythmias (heart rate <100 beats/min) the most common diagnoses are sinus bradycardia, second-degree atrioventricular block (AVB), or complete AVB (CAVB) [1–3]. Recent evidence suggests that even arrhythmias previously thought to be completely benign, such as ectopic beats, may be associated with prolongation of AV conduction, Sjögren’s antibody (SSA and SSB) exposure, and rarely, long QT syndrome (LQTS) [4–7]. Evaluation of all fetuses with irregular rhythm or inappropriate heart rate is warranted, especially if there is a family history of premature sudden cardiac arrest or perinatal loss.

Benign ectopy can be present only transiently for a few hours or may persist throughout pregnancy, labor, and into the neonatal period. Life-threatening arrhythmias are more often persistent and require emergent evaluation; in some cases treatment is required prenatally, postnatally, or both. Overall, the greatest risk is to the unborn fetus, because fewer diagnostic modalities and modes of treatment are available. The differential diagnoses for benign and life-threatening arrhythmias in the fetus are described later.

Ectopic contractions

Premature atrial contractions

The prevalence of fetal PACs to premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) is approximately 10:1 (Fig. 1). Ectopic premature supraventricular contractions in the fetus are usually idiopathic; however, some investigators have speculated that redundancy of the fossa ovalis flap may contribute in some cases to the triggering of ectopic foci in the atria. Some patulousness or enlargement of the fossa may be seen on fetal echocardiogram in a significant number of cases [8]. Fetal ectopy is associated with congenital cardiac defects in approximately 1% of cases [5,9]. Although rarely are associated conditions present, the most common are congenital heart disease, fetal cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, or fetal tumors.

Fig. 1.

Ectopy. The left panel shows a three-lead rhythm strip of PVCs marked by arrows. Note that no early P wave precedes these beats. The three subsequent panels show PACs conducted with a normal-appearing QRS and an aberrant QRS and not conducted through the AV node (arrows) (note the P waves).

Premature ventricular contractions

PVCs are diffcult to distinguish from PACs in utero; however, several echocardiographic characteristics are helpful, including the presence of AV valve regurgitation with the ectopic beat, less prominent flow reversal in the inferior vena cava by Doppler (with the ectopic beat), and a longer compensatory pause [1,2,9]. By M-mode, a cursor positioned through the atrium and ventricle demonstrates earliest ventricular activation. PVCs may be benign or be associated with systemic or cardiac diseases. In these cases, PVCs may be accompanied by structural and functional changes in the heart, such as ventricular dilatation or dysfunction, AVB, or repolarization abnormalities (Fig. 2). These changes may be caused by LQTS, cardiomyopathy, or immune-mediated or infectious myocarditis [1,2,4,5,9,10]. Currently, fetal echocardiography is the mainstay of diagnosis of associated conditions; however, it does not allow for assessment of QRS or QT interval and cannot evaluate some conditions. For congenital LQTS, magnetocardiography can confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 3) [11,12]. It is not currently available at most institutions, and high-risk patients may need to be referred regionally if this diagnosis is suspected on the basis of family history, bradycardia, or ventricular ectopy. Prenatal treatment has been successful for congenital LQTS [11,13].

Fig. 2.

Complex ventricular arrhythmias related to myocarditis, including couplets and nonsustained VT first noted by echo/Doppler (top tracing), in a 32-week gestation fetus evaluated by fMCG (middle tracing) and confirmed by postnatal monitoring (lower tracing).

Fig. 3.

Long QT syndrome. Two-lead fetal magnetocardiogram shows a markedly prolonged QT interval (lines). The P waves are noted by the arrows. This fetus had second-degree AVB.

Management of fetal ectopy

The greatest risk for PACs is their propensity to induce SVT in susceptible fetuses [14]. It occurs in approximately 1 in 200 ectopy cases and is more common if atrial couplets or triplets are noted during scanning. In general, isolated PACs or PVCs do not require antiarrhythmic therapy. Because of the slight association of congenital heart disease, progressive conditions, and SVT or atrial flutter, every fetus with ectopy should be evaluated with a complete fetal echocardiogram and Doppler assessment performed by a pediatric cardiologist experienced with fetal arrhythmia diagnosis and management [5].

The mother should be warned of the symptoms of fetal tachycardia, including an increase in abdominal and uterine girth secondary to polyhydramnios and a decrease in fetal movement. The patient with ectopy should be seen in the obstetric office no less than once a week for a hand-held Doppler auscultation of the fetal heart rate to rule out SVT. Ultrasound follow-up to look for development of chamber dilatation is advisable. The mother should avoid caffeine and sympathomimetic drug ingestion. If the arrhythmia resolves in utero, the mother can resume the routine follow-up schedule after 2 to 3 weeks. Atrial ectopy often shows as brief spikes on the fetal monitoring strips during labor. Caution should be exercised because rarely they have been interpreted as SVT, because the shortest ectopic interval traces momentarily at heart rates that exceeding 200 beats/min.

Occasionally, PACs persistently block at the AV node, which results in a slow rhythm called blocked atrial bigeminy (BAB) (Fig. 4). BAB often produces a characteristic flow reversal pattern in the inferior vena cava on ultrasound. Rates are usually in the 70s or higher. BAB has not been associated with hydrops; however, it has been associated with cardiovascular collapse in one infant during management of SVT postnatally, which suggests that caution should be exercised in administering rate-reducing medications after birth to infants who have had persistent BAB in utero. BAB can complicate labor monitoring when present, but it is unusual for sustained BAB to persist into late pregnancy.

Fig. 4.

Fetal heart rate trends demonstrate fetal rates frequently falling to approximately 75 beats/min. The lower two tracings show the fetal and composite maternal/fetal fMCG tracings during initially sinus rhythm then fetal BAB. Arrows depict the P waves.

Tachyarrhythmias

Sinus tachycardia

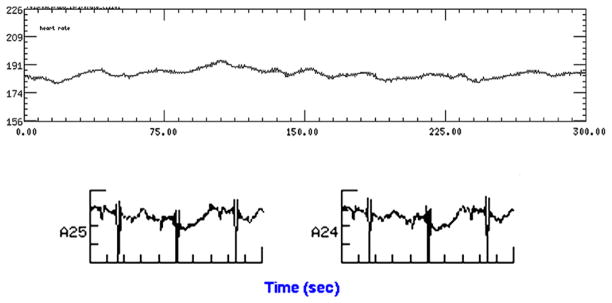

Sinus tachycardia is most often secondary to fetal systemic disease. It also can be caused by maternal hyperthyroidism. Approximately 17% of fetuses who have maternal thyrotoxicosis develop significant thyrotoxicosis (Fig. 5) [15].

Fig. 5.

This 17-week gestation fetus had evidence of clinical thyrotoxicosis with heart rates in the range of 180 to 192 beats/min. Note the beat-to-beat nonspecific T-wave changes in the lower tracing (signal averaged). This is consistent with T-wave alternans; however, it is not known whether T-wave alternans is an abnormal finding at this gestation and at this heart rate.

Supraventricular tachycardia

Approximately 1 in 200 fetuses who have frequent atrial ectopy develop SVT either in utero or in the first 3 to 4 weeks of life. The risk of SVT is increased to approximately 10% when ectopy is “re-entrant” (Fig. 6) or when complex ectopy (couplets, triplets) is noted [9,14]. Some fetuses present initially in SVT, however, and in those cases the initiating factors may not be as obvious. SVT can be either sustained or nonsustained, and only monitoring for several hours allows differentiation. More than 50% of fetuses who had SVT studied thus far by magnetocardiography showed evidence of the phenomenon of “re-entrant” ectopy [14]. Characteristics of “re-entrant” fetal ectopy include fixed or unvarying prematurity interval (the timing between the normal beat and the early beat), a bigeminal or trigeminal pattern (every other or every third beat is early), and frequency in excess of 20% of the P waves.

Fig. 6.

A slow re-entrant tachycardia at approximately 209 beats/min. The top tracing shows periods of atrial ectopy (saw tooth appearance) followed by SVT (solid line). The actocardiogram is shown on the bottom tracing. SVT onset is often linked to fetal movement, as shown by the minor deflections in the lower tracing.

Fetal SVT is usually characterized by a persistent tachycardia, which varies little in rate at ventricular rates of 210 to 320 beats/min. Heart rate is never irregular beat to beat during SVT, as seen with atrial flutter; however, it can start and stop abruptly and resume at the same rate (Fig. 7). SVT usually presents around 28 to 30 weeks’ gestation (but can be seen as early as 18 weeks). It leads rapidly to the development of hydrops fetalis when it is persistent for more than 12 hours or at rates of more than 230 beats/min. This risk relates primarily to the level of prematurity of the fetus (the younger fetus being more susceptible) and the duration of SVT and is not correlated to the specific rate of the SVT or to its ventriculoatrial interval [16]. The SVT is caused by an accessory re-entrant pathway located along the AV groove (tricuspid or mitral annulus), which electrically connects the ventricle with the atrium. Without an accessory connection, activation during the normal heart beat terminates in the ventricle. Conduction through the accessory pathway during periods of AV conduction delay can facilitate a stable form of re-entry, which activates the AV node in the forward (antegrade) direction, and the accessory pathway in the retrograde direction (orthodromic) [17]. These accessory connections may be multiple. Left-sided rather than right-sided pathways are most often present when there is hydrops fetalis [18]. Accessory connections are also thought to be the mechanism for re-entrant PACs. The development of hydrops is faster when there is a short interval (<50% of the R-R interval) from ventricular to atrial activation (see the lower tracing in Fig. 7) [19].

Fig. 7.

Initiation (top tracing) and termination (bottom tracing) of SVT from two fetuses. The top tracing shows a slow SVT with a long ventriculoatrial interval at approximately 200 beats/min, and the bottom tracing shows a rapid SVT with a shorter ventriculoatrial interval.

Symptoms of fetal SVT noted by the mother or the finding of a tachyarrhythmia during routine prenatal monitoring requires emergent referral to a high-risk perinatologist (maternal/fetal medicine specialist) and a pediatric cardiologist for specific treatment of the tachyarrhythmia. Delay in evaluation and treatment of fetal tachyarrhythmia may result in the development of hydrops fetalis. Outcomes of treatment from tertiary centers in which experience with SVT is greater and resources for monitoring mother and fetus are better have been superior to treatment in smaller hospitals [16]. Hydrops is unlikely to develop quickly when the fetal tachycardia rate is less than 220 beats/min (see the upper tracing in Fig. 7) or when intermittent and frequent breaks are present such that the fetus is only in tachycardia for less than 30% of the time. If ventricular dysfunction or AV valve regurgitation is present or if the fetus is less than 28 weeks’ gestation, these generally may not hold true and closer observation is required.

Fetal SVT can be either intermittent or sustained, which is usually determined by a period of in-hospital monitoring for 12 to 24 hours. Some fetuses with nonsustained SVT can later transition to sustained SVT. If infrequent (less than approximately 30% of the day) and intermittent and if not associated with hydrops fetalis, the SVT may be observed closely under the monitoring of a high-risk perinatologist, even when the fetal heart rates are relatively rapid. If the SVT is constant, the mother should be delivered if she is at term gestation or if preterm, the mother should be initially treated transplacentally. The exact first-line therapy varies. In some centers, including ours, the mother is rapidly loaded with digoxin intravenously [2,3,20–22]. In the absence of hydrops, digoxin by transplacental route is effective. When hydrops is present, concomitant administration of digoxin directly into the fetal thigh or hip (direct intramuscular administration) has been shown to enhance fetal digoxin levels and shorten the time to conversion of fetal tachycardia [23].

Oral absorption of digoxin is erratic and generally should be avoided initially, even in the nonhydropic fetus. Once the SVT has converted, transition to oral digoxin, along with frequent maternal serum digoxin concentration sampling, is recommended. Serum levels should be drawn during a trough period 6 to 12 hours after the most recent dose. The chronic oral dose of digoxin needed to maintain adequate serum levels is as much as 100% higher than in the nonpregnant state. In other centers, orally administered flecainide and sotalol have been used as first-line therapies in hydropic fetuses because of the superior conversion with these drugs when compared with digoxin; however, proarrhythmia (the worsening of arrhythmias because of a drug) and death have been observed in hydropic and nonhydropic fetuses with these two medications.

There is currently no consensus regarding the best second-line treatment, and amiodarone, flecainide, and sotalol have been reported to have good efficacy [2,3,21,22,24–31]. In our institution, amiodarone is preferred because of a low proarrhythmia potential; however, thyroid dysfunction is common with this drug. Usually the clinical onset of hypothyroidism occurs during neonatal continuation of the drug; however, clinical and biochemical hypothyroidism have been seen prenatally [31,32]. Cardioversion to sinus rhythm ranges from 65% to 95%, usually occurring about 6 to 10 days into treatment if the fetus is hydropic or sooner if nonhydropic. Detailed description of treatment regimens is beyond the scope of this article, and the references listed are excellent sources for fetal treatment.

Long-term prognosis after cardioversion is usually good. The overall mortality rate from treatment of SVT with hydrops varies between institutions from around 2% to as high as 30% [2,21–23,25,27,29,30,33–35]. Mortality has been highest using sotalol for SVT. Two new diagnostic tests may be helpful in better monitoring fetuses who have SVT: fetal magnetocardiography (fMCG) and gated tissue Doppler velocity imaging [14,36,37]. Both have allowed more precise assessment of conduction abnormalities, such as bundle branch block, which can be an early sign of fetal proarrhythmia. fMCG allows SVT mechanism assessment and precise assessment of repolarization, which can be dramatically altered by medications [7,38–40]. After delivery, approximately 50% of infants who have fetal tachycardia require no antiarrhythmic treatment and even more outgrow their need for medications by 1 year of age [2,16,41–43]. A late recurrence risk of approximately 30% for SVT is seen during teenage years in adolescents who have had SVT as infants.

Although rare forms of fetal tachycardia occur, such as junction ectopic tachycardia (JET) [44], atrial ectopic tachycardia, or permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia, they are not separately discussed in this article.

Atrial flutter

Atrial flutter is a less common form of tachycardia that accounts for approximately 25% of tachyarrhythmias in a fetus (Fig. 8). It often presents later than SVT and can be seen first during labor. It is associated with atrial rates of 330 to 500 beats/min and an irregular ventricular response (usually at ventricular rates of 190 to 240 beats/min). It also can lead to hydrops fetalis and is usually a persistent arrhythmia once present, [3,4,22,28,29,31,45]. Atrial flutter is associated with structural cardiac defects, chromosomal anomalies, and other pathologic states in approximately one third of cases noted early. It is commonly associated with re-entrant SVT and actually may develop because of degeneration of SVT caused by distention of the atrium during prolonged tachycardia. Roughly 70% of fetuses with idiopathic atrial flutter have accessory AV connections similar to that seen with SVT [16,43]. Mortality risk depends on associated conditions and whether hydrops is present, but reports suggest a mortality rate of 6% to 30%. The rate is probably much lower in near-term fetuses with minimal or no hydrops and no associated cardiac diseases. One recent report indicated no mortality when the drug sotalol was used [29].

Fig. 8.

Atrial flutter. The top tracing shows atrial flutter with 2:1 block. The atrial rate is 460 beats/min, and the ventricular rate is 230 beats/min. Flutter waves are marked with arrows. The QRS almost obscures the P wave. In a different patient in the lower two tracings, the administration of adenosine 100 μg/kg allows easy recognition of the rapid atrial flutter/fibrillation in this infant but does not terminate the tachycardia. Before adenosine, this rhythm could be mistaken for SVT. For this reason, during infusion of adenosine, continuous “real-time” paper recordings of the rhythm should be obtained.

The treatment for atrial flutter is similar to that for SVT; however, the ability to convert atrial flutter is not as high for amiodarone at 30%. For the fetus with hydrops, sotalol is recommended, and efficacy is reported to be as high as 80% [3,29,31]. In the term or near-term fetus without hydrops, rate control achieved with digoxin or delivery with subsequent cardioversion may be sufficient. The clinical management of any form of arrhythmia in the fetus must address the maternal-fetal-placental unit in its entirety [26]. Placental insufficiency has been documented in late gestation. The use of cordocentesis, multiple amniocenteses, and drugs with uterine tone effects can impact the pregnancy. Psychologically, many women experience a period of anxiety/depression during the inpatient treatment of tachyarrhythmias, and central nervous system side effects are common with many drugs. The doses of these medications can lead to maternal ECG and rhythm changes, which require close monitoring.

Bradyarrhythmias

Blocked atrial ectopy

Occasionally atrial ectopy in utero is associated with a bradyarrhythmia caused by block of the premature beat at the AV node (see Fig. 4). It can be seen when the coupling interval between the normal P wave and the premature P wave is short and occurs at a time when the AV node is refractory to depolarization. This functional bradyarrhythmia usually results in heart rates of 70 to 80 beats/min. In this fetal situation, AVB should be excluded. Characteristic patterns of flow reversal are seen in the inferior vena cava in association with the premature beat of BAB. Abnormal, early premature contractions may be seen on fetal M-mode. These pregnancies should not be delivered urgently without benefit of a fetal echocardiogram to clarify the diagnosis. Persistence as long as several weeks has been observed with this rhythm; however, BAB usually occurs only for a period of hours [1–3].

Sinus bradycardia

Sinus bradycardia with persistent heart rates less than 100 beats/min is uncommon [46]. In approximately 17% of fetuses, early persistent sinus bradycardia is caused by an inherited channelopathy, such as LQTS. Fetal sinus bradycardia not associated with LQTS usually does not require post-natal treatment, although follow-up with noninvasive 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring may be required. A small number of these infants show a progressive sinus node dysfunction. One case of sinus node dysfunction was associated with noncompaction of the ventricle [47]. Others have complete resolution of persistent bradycardia. The most common congenital heart disease associated with fetal bradycardia is heterotaxy syndrome. Infants who have polysplenia have a persistent low atrial or coronary sinus rhythm. Complete or second-degree AVB can be misidentified as sinus bradycardia.

Long QT syndrome

The diagnosis of LQTS can be made in utero using fMCG (see Fig. 3) [11,12,36,48]. In LQTS, fetal bradycardia is common and can be accompanied by other life-threatening arrhythmias [5,13,49]. Seventy-seven percent of 18 patients who had LQTS had bradycardia on cardiotochography, and 11% had some form of tachyarrhythmia in utero (most likely VT) [49]. When life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias are present, lidocaine and especially magnesium have been life saving (John Simpson, MD, personal communication) [13]. Although ventricular tachyarrhythmias are thought to be rare by current methods of echocardiographic and tocographic monitoring, fMCG has shown a substantially greater prevalence of VT, leading to the concept that brief but life-threatening fetal tachyarrhythmias may contribute to fetal demise more commonly than has been recognized.

Fetal bradycardia and second- or third-degree AVB associated with congenital LQTS have been recognized in utero (Fig. 9). LQTS may have variable severity of presentation; however, infants have a high incidence of cardiac arrest if inadequately treated, and novel defects in SCN5A sodium channels often have been observed [4,11–13,49,50]. Whenever possible, the associated finding of torsades de pointes VT should be excluded in fetal bradycardia. The combination of tachyarrhythmias and sinus bradycardia in a fetus should lead to a high index of suspicion for congenital LQTS. Postnatally, infants with second-degree AVB caused by LQTS should undergo pacemaker or defibrillator insertion. In these infants, medical therapy is required in addition to pacing [46,50,51]. Second-degree AVB has been observed with potassium channel and sodium channel defects.

Fig. 9.

Fetal LQTS with transient complete AVB, marked QT prolongation, and T-wave alternans.

Infants should be placed on beta-blocker therapy, working up the propranolol dose to 3 to 4 mg/kg/d divided every 8 hours. Transition to a longer-acting beta-blocker, such as nadolol, is desirable beyond a year of age, with dosing first twice daily and then, at an older age, once daily (Mike Ackerman, personal communication). If the QTc exceeds 600 ms, more aggressive treatment is indicated, including defibrillator implantation at the earliest feasible age. Nicarandil is available in some countries and has been used to shorten the QT interval. Likewise, mexiletine may be used. Genetic testing for LQT type should be performed, although the treatment decisions usually must be made before results are received [50,52]. The family may choose to obtain an automated external defibrillator for their home, especially if there is more than one affected family member.

Second-degree and complete atrioventricular block

Partial or complete AVB in the fetus is associated with structural cardiac defects in approximately 50% of cases [4]. The intrauterine and early neonatal death rate for CAVB with congenital heart disease is as high at 70% [10,53]. Second-degree or CAVB in the absence of structural heart defect is usually associated with collagen vascular diseases of the mother. Maternal SS-A/Ro and SS-B/La antibodies, which result from maternal systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, Sjögren’s syndrome, or mixed-type, cause an inflammatory myocarditis and disrupt the developing fetal heart conduction system between approximately 18 and 32 weeks’ gestation [54–58]. There has been some debate about the mode by which heart block develops, but recent study suggested that it is sudden onset. Although serial echocardiographic evaluation (mechanical PR interval) of fetuses of SSA- or SSB-positive mothers is usually recommended every 2 weeks, it is evident that the traditional method [59] overestimates the PR interval [5,60]. We have used the method suggested by Bergman and colleagues [61] to evaluate the mechanical PR interval.

Intrapartum management is sometimes required for a fetus with CAVB, especially if the fetus has shown signs of hydrops or poor heart rate variability. The ability to provide external pacing or rapid balloon pacing catheter insertion should be available for high-risk fetuses after delivery; thus, they should not be delivered in centers without a team approach to high-risk perinatal care [6,10,62]. Immediately after delivery, the ventricular rate can be higher than in utero rate, and these infants need to be observed closely in an intensive care unit setting for the first 24 to 48 hours, when the heart rate and variability can decline rapidly and result in metabolic acidosis. We have begun to use fMCG (Fig. 10) to predict variability prenatally, and we use periodic blood gas assessment in the first 48 hours to detect subclinical metabolic acidosis in unpaced newborns.

Fig. 10.

Fetal heart rate and movement trends over 5 minutes in a fetus with CAVB and congenital heart disease. Note the flat heart rate tracing. The fetus requires postnatal pacemaker insertion. On the bottom tracing, in addition to the third-degree AVB, the corrected QT interval is also prolonged at 0.59 sec.

In utero and peripartum management of congenital atrioventricular block

In utero, congenital AVB in association with cardiac defects has a poor prognosis and few treatment options [25,54,56,63]. If hydrops develops because of low ventricular rate, early delivery may be required, and deterioration in status in utero is sometimes heralded by the development of oligohydramnios, poor fetal growth, and ventricular arrhythmias. Beta sympathomimetic agents, such as intravenous salbutamol or oral terbutaline, have been shown to raise ventricular rate by as much as 20%. It is unclear, however, whether they improve overall mortality [1,64,65]. Recently, our group reported on the electrophysiologic effects of terbutaline in fetuses with and without congenital heart disease [66]. If the heart is structurally normal and CAVB is associated with maternal lupus autoantibodies (SSA or SSB), administration of betamethasone or dexamethasone has been shown to improve ventricular function and survival [67]. Recent studies suggested that it is ineffective in reversing complete heart block, however, and the long-term side effects may outweigh the advantages of its prolonged use [54,68,69]. It seems to play a role in situations in which progression of second-degree AVB has been arrested. It should be noted that maternally administered prednisone or prednisolone does not cross the placental barrier and cannot be used as a substitute for dexamethasone. The mother and the infant require gradual tapering from the prenatal steroid regimen after delivery, and stress dosing of steroids is usually needed for several months because of inadequate adrenal cortex function.

Neonatal arrhythmias: diagnosis and management

Ectopic contractions

Ectopic beats

Irregularities of heart rhythm in normal newborns are generally limited to occasional premature supraventricular or ventricular beats (see Fig. 1). In healthy newborns these occasional ectopic beats are most often self-limiting and disappear when infants grow older, often within weeks of their appearance [17]. Atrial extrasystoles are distinguished from ventricular extrasystoles by a premature P wave with a different morphology than the sinus morphology that precedes the QRS complex. They may be obscured by the T wave and should be sought carefully. PACs predispose to SVT in approximately 1 in 200 infants. Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are not preceded by P waves and have a wider and different morphology than the sinus QRS. Although PACs can have a wide QRS because of aberrancy, they are always preceded by a P wave. Rarely, “late” PVCs that are close to the sinus rate may be preceded by a P wave, but this P wave is never early. Etiologic factors were reviewed in the previous section on fetal ectopy.

Treatment is not required. PVCs require more specific evaluation to exclude myocarditis, LQTS, and their complications. In general, maternal caffeine QT-prolonging drugs and sympathomimetic drugs should be avoided if the mother is breast feeding.

Management of persistent fetal ectopy

We obtain a single ECG after delivery for fetuses with PVCs or persistent atrial ectopy. The absence of QT prolongation and the type of ectopy usually can be confirmed. Routine 24-hour ambulatory Holter monitoring is not necessary for fetal supraventricular ectopy; however, it is advisable for ventricular ectopy because of the association of PVCs with more complex ventricular arrhythmias [2]. We have performed neonatal echocardiograms on infants with documented ventricular ectopy but not for uncomplicated atrial ectopy as long as prior ultrasound results were negative. Infants can be seen in the pediatric cardiology clinic at 1 month of age if they have ventricular ectopy or if they have frequent PACs that persist beyond the first 2 weeks of life. In general, once ectopy has resolved, long-term follow-up is not required in infants without QT prolongation. The long-term prognosis is excellent, and most infants who have ectopy have complete resolution.

Sinus arrhythmia and sinus pauses

Sinus arrhythmia can be a normal variant in newborns [17]. During sinus arrhythmia, the heart rate slows during expiration and increases during inspiration. This rhythm may become more pronounced during febrile conditions [17]. Sinus pauses of up to 1.5 seconds sometimes can be seen in healthy infants.

Tachyarrhythmias

Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias

The most common life-threatening arrhythmia of newborns is SVT. The diagnosis of SVT in a newborn may be difficult because of the normally more rapid heart rate in infancy. Infants who are feeding poorly, tachypneic, and irritable and have heart rates of 200 to 300 beats/min are sometimes misdiagnosed as septic; SVT can be overlooked and sometimes can go unrecognized by parents and medical caregivers until signs of cardiac failure begin.

In infants, SVT may be differentiated from sinus tachycardia if the rate is unvarying and more than 230 beats/min with an abnormal P wave axis. In most cases the SVT rate is distinguishing; however, when an infant is ill because of sepsis or myocarditis, sinus tachycardia can exceed 230 beats/min. Interventions for fever control, pain control, and sedation usually bring the heart rate into the usual range for sinus tachycardia. If not, other therapeutic interventions, such as intravenous adenosine, may be used along with inpatient observation (Fig. 11). Rare forms of atrial ectopic tachycardia may be distinguished by electrocardiogram, Holter or telemetry monitoring, or variable or unusual P wave morphology.

Fig. 11.

SVT termination. SVT is present initially. After administration of adenosine 100 μg/kg by rapid intravenous administration, the SVT terminates and there is a sinus pause caused by the vagal effects of the drug. The terminations always should be recorded, because sometimes the presence of Wolff-Parkinson-White pre-excitation is only seen transiently. Note here the short PR interval and delta wave on the two beats after termination.

Most cases of SVT are caused by an accessory AV conduction, most commonly along the left AV junction. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is present in 16% to 26% of infants. The higher percentage reflects studies in which pacing maneuvers were instituted, as is noted after conversion in Fig. 11 [16,70]. In Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, the accessory connection conducts prograde from atria to ventricles, which results in premature activation of the ventricle and produces an abnormally wide QRS with shortened PR interval and delta waves (slurred onset of the QRS). Using various algorithms, the location of the pathway can be predicted [71].

Treatment of supraventricular arrhythmias in children younger than 1 year is by medical therapy rather than ablation [72]. Acute management with adenosine in the emergency room setting is usually effective; however, rare complications have been reported [73]. The pharmacologic treatment of SVT caused by an accessory connection is complex, and many excellent resources are available. Initial treatment is usually with a beta-blocker, such as propranolol, given three or four times daily. Digoxin, once commonly used for neonatal SVT, has been used recently only in the absence of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, because it has been implicated as a cause of ventricular fibrillation. It also complicates safety of electrical cardioversion. Acute treatment of SVT should be performed after intravenous access has been established in infants who present for the first time to the emergency room. Profound bradycardia and cardiac arrest have been reported after all techniques of SVT termination, including ice application.

An ice bag placed over the infant’s face for 15 to 20 seconds may terminate the SVT episode. If the SVT is persistent, rapid infusion of intravenous adenosine (0.05–0.3 mg/kg) is the first choice for infants younger than 1 year [17]. If an infant is hemodynamically unstable, synchronized cardioversion at 0.5 to 1 W sec/kg is instituted. Approximately 40% of newborns with a treated episode of SVT do not have another episode when treated with antiarrhythmic agents for a minimum of 6 months after the first episode. If SVT persists beyond 1 year, spontaneous resolution is unlikely. Ablation usually can be performed electively when an infant is approximately 15 kg; however, the long-term potential for coronary artery stenosis has not been excluded fully in children undergoing ablation at the youngest ages.

Multifocal or chaotic atrial tachycardia

Multifocal atrial tachycardia, sometimes called chaotic atrial tachycardia, can occur in normal infants usually younger than 1 year, and it disappears spontaneously around the age of 3 (Fig. 12) [17]. This type of tachycardia is characterized by three or more ectopic P waves with three or more different ectopic P-P cycles with varying PR intervals and blocked P waves. It is commonly associated with atrial septal defects and other congenital heart defects, and it often fails to suppress completely with antiarrhythmic drugs [74,75]. Multifocal atrial tachycardia is refractory to vagal maneuvers, adenosine, and cardioversion. Beta-blockers in combination with amiodarone are sometimes used. In cases refractory to drugs, surgical ablation may be the necessary treatment [17].

Fig. 12.

Chaotic (multifocal) atrial tachycardia. Note the changing patterns of atrial rhythm on the two-lead rhythm strips. Chaotic atrial tachycardia often varies in rate and rhythm, with some periods resembling atrial flutter and other periods resembling complex atrial ectopy. Some sinus rhythm also can be noted (top tracing, right side).

Accelerated ventricular rhythm

Accelerated idioventricular rhythm is a sustained VT that can occur in newborns with normal hearts and is more benign than VT. There are periods of fusion with sinus rhythm, and the QRS complex is wide during this tachycardia. The rhythm is regular with a rate close to that of the normal sinus rate (Fig. 13). Accelerated idioventricular rhythm is a slow, self-limited form of VT that usually requires no medical treatment as long as the cardiac output remains normal. VT in normal infants is rare, and treatment depends on hemodynamic status [17]. It most often disappears before 2 to 3 months of age [33]. Careful observation and occasional Holter monitoring should be used to determine recurrence of this arrhythmia.

Fig. 13.

Accelerated ventricular rhythm. Three-lead rhythm strip recorded at differing paper speeds shows the infant transitioning from sinus rhythm to accelerated ventricular rhythm on multiple occasions. Note the changing QRS morphology with wide QRS. The heart rate does not vary much with the change in rhythm.

Junctional and ventricular tachyarrhythmias

Junctional (JET) and ventricular tachyarrhythmias are most often secondary to underlying cardiac abnormalities. Infants with frequent episodes of paroxysmal rapid VT or JET without previously diagnosed heart disease have a high incidence of myocarditis, myocardial hamartomatous “tumors,” or genetic cardiomyopathies involving ion channels [76–79]. Hamartomas can be missed echocardiographically. MRI may be helpful because they may represent a clinical stage of myocarditis. The prognosis for VT in infants without symptoms and without progressive underlying disease seems to be good. JET has been associated with maternal Sjögren’s antibodies, and AV conduction system disease could develop [44].

It is critical to distinguish SVT from VT correctly before instituting treatment. In VT, P waves are absent or dissociated, and the QRS complexes are of different morphology than the sinus QRS. Although wide, the QRS duration for a newborn is narrow (maximally 80 ms) and may not appear to the clinician as wide (Fig. 14). The presence of a tachyarrhythmia with AV dissociation with a QRS duration that exceeds the normal range should be treated as VT. Treatment of VT is often difficult, and success depends on the underlying cause. Often multiple antiarrhythmic medications are required, usually including a beta-blocker, amiodarone, or sotalol. Sometimes a class I agent, such as procainamide or flecainide, is added.

Fig. 14.

Ventricular tachycardia. In the infant, ventricular tachycardia can be mistaken for supraventricular tachycardia, because the QRS is often only slightly wider than normal. The normal QRS duration in an infant is less than 0.08 seconds. Note in lead V1 that there is AV dissociation during tachycardia (arrows depict the P waves). This infant had an LV tumor.

Bradyarrhythmias

Sinus bradycardia

Generally, sustained sinus bradycardia in a newborn (a heart rate <90 beats/min) is secondary to underlying systemic diseases, including congenital heart defects, central nervous system disease, inadvertent poisoning, or metabolic conditions. Usually treatment is not required. Treatment of the underlying condition is the goal. If severe and symptomatic, atropine or intravenous sympathomimetics, such as isoproterenol or epinephrine, can be used. Temporary external ventricular pacing can be used in an arrest situation. For infants with cardiac disease, a history of digoxin, propranolol, or other drug exposure should be sought, because inadvertent dosing errors can occur and may require digoxin-binding agents.

Complete atrioventricular block

Newborns with congenital complete AVB often do not require pacing unless heart rates are below 50 beats/min with signs of prior hydrops or current heart failure or metabolic acidosis (Fig. 15) [80]. Atropine, isoproterinol, or epinephrine can be used to attempt to increase the heart rate temporarily until emergent pacemaker placement is completed [49]. New prenatal techniques can be used to assess the AVB and help predict need for neonatal pacing [10].

Fig. 15.

Third-degree AVB. Twelve-lead ECG showing third-degree CAVB. The atrial rate is 166 beats/min, whereas the ventricular rate is only 48 beats/min. Note the AV dissociation with P waves (arrows) marching through the onset of the QRS. Also note that the QT is prolonged.

In some infants born of mothers with undiagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus or asymptomatic SSA disease, heart block may go undetected after birth until bradycardia is noted at an older age. Pacing indications have been outlined for infants and children [80].

CAVB in the absence of structural heart defect is associated with a relatively good prognosis, especially if dexamethasone was administered in utero [67]. Indications for cardiac pacing have been described [80]. Pacing should be implemented in infants for a ventricular rate less than 50 beats/in in infants with no structural heart disease (70 beats/min if structural heart disease), a wide complex QRS (>80 ms), complex ventricular arrhythmias, or significant ventricular dysfunction or hydrops. Several studies have evaluated the long-term complications of isoimmune AVB. Late cardiomyopathy and ventricular dysfunction have been described in a significant percentage of patients [51,81].

References

- 1.Ferrer PL. Fetal arrhythmias. In: Deal B, Wolff GS, Gelband H, editors. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias in infants and children. Armonk (NY): Futura Publishing Company, Inc; 1998. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strasburger JF. Fetal arrhythmias. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;11:1. doi: 10.1016/s1058-9813(00)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson J. Fetal arrhythmias. In: Allen L, Hornberger LK, Sharland G, editors. Textbook of fetal cardiology. London: Greenwich Medical Media, Limited; 2000. p. 421. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuneo BF. Outcome of fetal cardiac defects. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:490. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245348.52960.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Wakai RT, et al. Conduction system disease in fetuses evaluated for irregular cardiac rhythm. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2006;21:307. doi: 10.1159/000091362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuneo BF, Wakai RT, Strasburger JF, et al. Conduction system disease in fetuses with irregular rhythm diagnosed in utero by abnormal mechanical pr interval and confirmed by fetal magnetocardiography. Fetal Diagn Ther. doi: 10.1159/000091362. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao H, Strasburger JF, Cuneo BF, et al. Fetal cardiac repolarization abnormalities. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:491. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toro L, Weintraub RG, Shiota T, et al. Relation between persistent atrial arrhythmias and redundant septum primum flap (atrial septal aneurysm) in fetuses. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:711. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90942-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson J, Yates R, Sharland G. Irregular heart rate in the fetus: not always benign. Cardiol Young. 1996;6:28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao H, Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, et al. Electrophysiologic characteristics of fetal AV block. J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.060. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamada H, Horigome H, Asaka M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of long QT syndrome using fetal magnetocardiography. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:697. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199907)19:7<677::aid-pd597>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menendez T, Achenbach S, Hofbeck M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of QT prolongation by magnetocardiography. PACE. 2000;23:1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuneo BF, Ovadia M, Strasburger JF, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and in utero treatment of torsades de pointes associated with congenital long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1395. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakai RT, Strasburger JF, Li Z, et al. Magnetocardiographic rhythm patterns at initiation and termination of fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2003;107:307. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043801.92580.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peleg D, Cada S, Peleg A, et al. The relationship between maternal serum thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin and fetal and neonatal thyrotoxicosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1040. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naheed Z, Strasburger J, Deal B, et al. Fetal tachycardia: mechanisms and predictors of hydrops fetalis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1736. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fish F, Benson DW., Jr . Disorders of cardiac rhythm and conduction. In: Allan H, Gutgesell H, Clark E, et al., editors. Heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2001. p. 518. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannankeril PJ, Gotteiner NL, Deal BJ, et al. Location of accessory connection in infants presenting with supraventricular tachycardia in utero: clinical correlations. Am J Perinatol. 2003;20:115. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strasburger J, Duffy C, Gidding S. Abnormal systemic venous Doppler flow patterns in atrial tachycardia in infants. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:640. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fyfe D, Meyer K, Case C. Sonographic assessment of fetal cardiac arrhythmias. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1993;14:286. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(05)80103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson J. Fetal tachycardias: management and outcome of 127 consecutive cases. Heart. 1998;79:576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Engelen A, Weijtens O, Brenner J, et al. Management outcome and follow-up of fetal tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1371. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parilla B, Strasburger J, Socol M. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia complicated by hydrops fetalis: a role for direct fetal intramuscular therapy. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13:483. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allan L, Chita S, Sharland G, et al. Flecainide in the treatment of fetal tachycardias. Br Heart J. 1991;65:46. doi: 10.1136/hrt.65.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuneo B, Strasburger JF. Management strategies for fetal tachycardia. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:575. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornberger LK, Sahn DJ. Rhythm abnormalities of the fetus. Heart. 2007;93:1294. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.069369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jouannic JM, Delahaye S, Fermont L, et al. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia: a role for amiodarone as second-line therapy? Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:152. doi: 10.1002/pd.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krapp M, Kohl T, Simpson JM, et al. Review of diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of fetal atrial flutter compared with supraventricular tachycardia. Heart. 2003;89:913. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oudijk MA, Michon MM, Kleinman CS, et al. Sotalol in the treatment of fetal dysrhythmias. Circulation. 2000;101:2721. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.23.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonesson SE, Fouron JC, Wesslen-Eriksson E, et al. Foetal supraventricular tachycardia treated with sotalol. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:584. doi: 10.1080/08035259850158335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strasburger JF, Cuneo BF, Michon MM, et al. Amiodarone therapy for drug-refractory fetal tachycardia. Circulation. 2004;109:375. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109494.05317.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lomenick JP, Jackson WA, Backeljauw PF. Amiodarone-induced neonatal hypothyroidism: a unique form of transient early-onset hypothyroidism. J Perinatol. 2004;24:397. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Copel J, Friedman A, Kleinman C. Management of fetal cardiac arrhythmias. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:201. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gembruch U, Redel DA, Bald R, et al. Longitudinal study in 18 cases of fetal supraventricular tachycardia: Doppler echocardiographic findings and pathophysiologic implications. Am Heart J. 1993;125:1290. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90997-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perry J, Ayres N, Carpenter R., Jr Fetal supraventricular tachycardia treated with flecainide acetate. J Pediatr. 1991;118:303. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menendez T, Achenbach S, Beinder E, et al. Magnetocardiography for the investigation of fetal arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(3):334–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rein AJ, O’Donnell C, Geva T, et al. Use of tissue velocity imaging in the diagnosis of fetal cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation. 2002;106:1827. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031571.92807.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall CM, Ward Platt MP. Neonatal flecainide toxicity following supraventricular tachycardia treatment. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:1343. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasheed A, Simpson J, Rosenthal E. Neonatal ECG changes caused by supratherapeutic flecainide following treatment for fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Heart. 2003;89:470. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.4.470-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trotter A, Kaestner M, Pohlandt F, et al. Unusual electrocardiogram findings in a preterm infant after fetal tachycardia with hydrops fetalis treated with flecainide. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;21:259. doi: 10.1007/s002460010053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pongiglione G, Strasburger J, Deal B, et al. Use of amiodarone for short-term and adjuvant therapy in young patients. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:603. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90351-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samson RA, Deal BJ, Strasburger JF, et al. Comparison of transesophageal and intracardiac electrophysiologic studies in characterization of supraventricular tachycardia in pediatric patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:159. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Till J, Wren C. Atrial flutter in the fetus and young infant: an association with accessory conduction. Br Heart J. 1995;67:80. doi: 10.1136/hrt.67.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubin AM, Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, et al. Congenital junctional ectopic tachycardia and congenital complete atrioventricular block: a shared etiology? Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:313. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casey F, McCrindle B, Hamilton R, et al. Neonatal atrial flutter: significant early morbidity and excellent long-term prognosis. Am Heart J. 1997;133:302. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin MT, Hsieh FJ, Shyu MK, et al. Postnatal outcome of fetal bradycardia without significant cardiac abnormalities. Am Heart J. 2004;147:540. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozkutlu S, Onderoglu L, Karagoz T, et al. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium with fetal sustained bradycardia due to sick sinus syndrome. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48:383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hofbeck M, Ulmer H, Beinder E, et al. Prenatal findings in patients with prolonged QT interval in the neonatal period. Heart. 1997:77. doi: 10.1136/hrt.77.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beinder E, Grancay T, Menendez T, et al. Fetal sinus bradycardia and the long QT syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:743. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lupoglazoff JM, Denjoy I, Villain E, et al. Neonatal forms of congenital long QT syndrome. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004;97:479. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villain E, Marijon E, Georgin S. Is isolated congenital heart block with maternal antibodies a distinct and more severe form of the disease in childhood? Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:S45. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shim SH, Ito M, Maher T, et al. Gene sequencing in neonates and infants with the long QT syndrome. Genet Test. 2005;9:281. doi: 10.1089/gte.2005.9.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt KG, Ulmer HE, Silverman NH, et al. Perinatal outcome of fetal complete atrioventricular block: a multicenter experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1360. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Copel J, Buyon J, Kleinman C. Successful in utero therapy of fetal heart block. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1384. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman DM, Rupel A, Buyon JP. Epidemiology, etiology, detection, and treatment of autoantibody-associated congenital heart block in neonatal lupus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:101. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groves A, Allan L, Rosenthal E. Outcome of isolated congenital complete heart block diagnosed in utero. Heart. 1996;75:190. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Izmirly PM, Rivera TL, Buyon JP. Neonatal lupus syndromes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:267. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson W, Katz V. Steroid therapy for hydrops associated with anti-body mediated congenital heart block. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991:165. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90282-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glickstein J, Buyon J, Kim M, et al. The fetal Doppler mechanical PR interval: a validation study. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19:31. doi: 10.1159/000074256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pasquini L, Seale AN, Belmar C, et al. PR interval: a comparison of electrical and mechanical methods in the fetus. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(4):231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bergman G, Jacobsson LA, Wahren-Herlenius M, et al. Doppler echocardiographic and electrocardiographic atrioventricular time intervals in newborn infants: evaluation of techniques for surveillance of fetuses at risk for congenital heart block. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:57. doi: 10.1002/uog.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cuneo BF, Zhao H, Strasburger JF, et al. Atrial and ventricular rate response and patterns of heart rate acceleration during maternal-fetal terbutaline treatment of fetal complete heart block. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:661. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishimaru S, Izaki S, Kitamura K, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus: dissolution of atrioventricular block after administration of corticosteroid to the pregnant mother. Dermatology. 1994;189:92. doi: 10.1159/000246940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Groves A, Allan L, Rosenthal E. Therapeutical trial of sympathomimetics in three cases of complete heart block in the fetus. Circulation. 1995;92:3394. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopez L, Cha S, Leone C, et al. Use of sympathomimetic agents in fetal atrioventricular block. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1994;63:297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Zhao H, et al. Electrophysiologic patterns of fetal heart rate augmentation with terbutaline in complete AV block. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:S45. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaeggi ET, Fouron JC, Silverman ED, et al. Transplacental fetal treatment improves the outcome of prenatally diagnosed complete atrioventricular block without structural heart disease. Circulation. 2004;110:1542. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142046.58632.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breur JM, Visser GH, Kruize AA, et al. Treatment of fetal heart block with maternal steroid therapy: case report and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:467. doi: 10.1002/uog.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raboisson MJ, Fouron JC, Sonesson SE, et al. Fetal Doppler echocardiographic diagnosis and successful steroid therapy of Luciani-Wenckebach phenomenon and endocardial fibroelastosis related to maternal anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:375. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Newburger J, Keane J. Intrauterine supraventricular tachycardia. J Pediatr. 1979;95:780. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80736-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arruda MS, McClelland JH, Wang X, et al. Development and validation of an ECG algorithm for identifying accessory pathway ablation site in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:2. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paul T, Bertram H, Bokenkamp R, et al. Supraventricular tachycardia in infants, children and adolescents: diagnosis, and pharmacological and interventional therapy. Paediatr Drugs. 2000;2:171. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200002030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jaeggi E, Chiu C, Hamilton R, et al. Adenosine-induced atrial pro-arrhythmia in children. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dodo H, Gow RM, Hamilton RM, et al. Chaotic atrial rhythm in children. Am Heart J. 1995;129:990. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fish FA, Mehta AV, Johns JA. Characteristics and management of chaotic atrial tachycardia of infancy. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:1052. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davis AM, Gow RM, McCrindle BW, et al. Clinical spectrum, therapeutic management, and follow-up of ventricular tachycardia in infants and young children. Am Heart J. 1996;131:186. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kearney DL, Titus JL, Hawkins EP, et al. Pathologic features of myocardial hamartomas causing childhood tachyarrhythmias. Circulation. 1987;75:705. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perry JC. Ventricular tachycardia in neonates. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1997;20:2061. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb03628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zeigler VL, Gillette PC, Crawford FA, Jr, et al. New approaches to treatment of incessant ventricular tachycardia in the very young. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:681. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gregoratos G, Abrams J, Epstein AE, et al. ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/NASPE Committee to Update the 1998 Pacemaker Guidelines) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1703. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moak JP, Barron KS, Hougen TJ, et al. Congenital heart block: development of late-onset cardiomyopathy, a previously underappreciated sequela. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:238. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]