Abstract

Background and Aims

Hydrophytes generally exhibit highly acquisitive leaf economics. However, a range of growth forms is evident, from small, free-floating and rapidly growing Lemniden to large, broad-leaved Nymphaeiden, denoting variability in adaptive strategies. Traits used to classify adaptive strategies in terrestrial species, such as canopy height, are not applicable to hydrophytes. We hypothesize that hydrophyte leaf size traits and economics exhibit sufficient overlap with terrestrial species to allow a common classification of plant functional types, sensu Grime's CSR theory.

Methods

Leaf morpho-functional traits were measured for 61 species from 47 water bodies in lowland continental, sub-alpine and alpine bioclimatic zones in southern Europe and compared against the full leaf economics spectrum and leaf size range of terrestrial herbs, and between hydrophyte growth forms.

Key Results

Hydrophytes differed in the ranges and mean values of traits compared with herbs, but principal components analysis (PCA) demonstrated that both groups shared axes of trait variability: PCA1 encompassed size variation (area and mass), and PCA2 ranged from relatively dense, carbon-rich leaves to nitrogen-rich leaves of high specific leaf area (SLA). Most growth forms exhibited trait syndromes directly equivalent to herbs classified as R adapted, although Nymphaeiden ranged between C and SR adaptation.

Conclusions

Our findings support the hypothesis that hydrophyte adaptive strategy variation reflects fundamental trade-offs in economics and size that govern all plants, and that hydrophyte adaptive strategies can be directly compared with terrestrial species by combining leaf economics and size traits.

Keywords: Aquatic plant, plant functional type, plant economics spectrum, universal adaptive strategy theory, worldwide leaf economics spectrum

INTRODUCTION

The worldwide leaf economics spectrum (Wright et al., 2004) describes a widespread gradient in leaf trait variability reflecting a trade-off between acquisitive and conservative leaf functioning. This relationship is hypothesized to be a universal characteristic of the plant kingdom, ‘a tradeoff between attributes conferring an ability for high rates of resource acquisition in productive habitats and those responsible for retention of resource capital in unproductive conditions’ (Grime et al., 1997), and has been proposed as one of the key determinants of plant adaptive strategies (Grime, 2001). Leaf economics forms only a part of the overall plant economics spectrum (Grime et al., 1997; Freschet et al., 2010) that, in turn, is associated with only one of the main axes of trait variation evident for terrestrial plants (Díaz et al., 2004; Cerabolini et al., 2010a). Three main directions of evolutionary specialization exist, ‘with extreme strategies facilitating the survival of genes via: (C). the survival of the individual using traits that maximise resource acquisition and resource control in consistently productive niches, (S). individual survival via maintenance of metabolic performance in variable and unproductive niches, or (R). rapid gene propagation via rapid completion of the lifecycle and regeneration in niches where events are frequently lethal to the individual’ (reviewed by Grime and Pierce, 2012).

However, one of the practical difficulties in classifying and comparing organisms with contrasting life histories is the lack of common traits. For instance, Hodgson et al.'s (1999) CSR classification scheme, now applied to >1000 terrestrial herbaceous and woody species in a range of habitats throughout Europe (Caccianiga et al., 2006; Pierce et al., 2007a, b; Simonová and Lososová, 2008; Massant et al., 2009; Cerabolini et al., 2010a, b; Kilinç et al., 2010; Navas et al., 2010), assigns an index of competitive ability, or C adaptation, based in part on the trait canopy height. Weiher et al. (1999) suggest that ‘height should be measured as the difference between the elevation of the highest photosynthetic tissue in the canopy and the base of the plant’. For aquatic macrophytes, canopy height is a difficult measure to apply where different growth forms position leaves equally at the air–water interface but may be free floating or anchored to the substrate. Hydrophytes are often classified in terms of CSR strategies (e.g. Kautsky, 1988; Murphy et al., 1990; Lehmann et al., 1997; Greulich and Bornette, 1999), but this has previously relied on inference of the degree of stress tolerance from measures of depth and light availability, which are not directly comparable with the leaf economics traits, size traits and phenological traits used in CSR classification (Hodgson et al., 1999).

However, physical size, at least in productive niches, is a fundamental determinant of the ability to acquire resources (Grime and Pierce, 2012), and forms an axis of trait variability distinct from that of the plant economics spectrum (Díaz et al., 2004; Cerabolini et al., 2010a). Thus we hypothesize that economics and size traits (particularly area and mass) provide common points of reference, available from leaf material, which could potentially be used to compare the primary adaptive strategies of hydrophytes and terrestrial species directly.

Poorter et al. (2009) included hydrophytes in their review of leaf mass per area (LMA – a key indicator of leaf economics) and found that hydrophytes exhibited the lowest LMA values (i.e. highly acquisitive physiologies) compared with a range of terrestrial plant growth forms. However, all freshwater species were amalgamated into a single growth form category that actually masks a range of highly divergent life history strategies. These include free-floating leafy forms, such as Lemna minor [the species with the highest relative growth rate (RGR) ever measured; Grime et al., 2007], and large species anchored to the substrate with extensive rhizome systems and with slower growth rates, such as the water lilies (e.g. Nymphaea alba). The variation in economics between these diverse hydrophyte groups, and specifically its relationship to contrasting hydrophyte growth forms, is not understood. A number of growth form classification systems exist that can bring order to studies of hydrophyte functional biology, the most recent and comprehensive being that of Wiegleb (1991), summarized in Table 1. This system classifies hydrophytes based on a small number of key criteria, such as whether the plant is anchored to the substrate by roots or is free floating, whether the leaves are submerged, float or emerge from the water, and leaf form and arrangement.

Table 1.

Hydrophyte growth forms according to Wiegleb (1991)

| Growth form | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Batrachiden | Anchored plants with both floating and submerged leaves that are entire or compound. |

| Ceratophylliden | Free-floating plants with submerged finely divided leaves. |

| Elodeiden | Anchored submerged plants with whorls of small, undivided leaves. |

| Herbiden | Anchored herbaceous plants similar in phenotype to terrestrial herbs. |

| Hydrochariden | Free-floating plants with large leaves. |

| Isoetiden | Anchored plants with basal buds and stiff, narrow leaves. |

| Lemniden | Floating plants composed mainly of small leaves. |

| Nymphaeiden | Anchored plants with floating leaves attached to a submerged rhizome by an elongate petiole. |

| Magnopotamiden | Anchored submerged plants with large, entire leaves. |

| Myriophylliden | Anchored submerged plants with long stems and finely divided leaves. |

| Parvopotamiden | Anchored submerged plants with small, entire leaves and sympodial shoots. |

| Pepliden | Anchored plants with elongated or spathulate leaves forming a terminal rosette adapted for emergence into the atmosphere. |

| Riccielliden | Free-floating but submersed plants with small, entire leaves. |

| Stratiotiden | Free-floating plants with emerging leaves. |

| Vallisneriden | Anchored plants with long, floating basal leaves. |

The present study aims to compare variation in a range of traits to determine whether hydrophyte leaf characteristics co-vary in a manner consistent with terrestrial species, allowing a consistent CSR classification system for hydrophytes, and whether differences in primary adaptive strategy are apparent between hydrophyte growth forms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material was collected from 47 water bodies (12 lakes, four marshes, four peat bogs, 19 irrigation canals, seven ponds and one spring) over a wide range of bioclimatic zones spanning alpine to lowland sites in northern Italy, between the months of July and September 2009. Whenever necessary, plant material was collected using a rowing boat. Ten fully expanded, intact leaves of each species were collected from separate individuals of 61 species representing 21 families (for species list see Table 2; species nomenclature follows Pignatti, 1982), with each species collected from a single site.

Table 2.

Leaf traits of 61 hydrophyte species

| Binomial | Growth form | LA (mm2) | LFW (mg) | LDW (mg) | LDMC (%) | SLA (mm2 mg−1) | LNC (%) | LCC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alisma gramineum Lej. subsp. gramineum | Vallisneriden | 4825·5 ± 994·43 | 3452·81 ± 614·98 | 209·44 ± 39·12 | 6·1 ± 0·27 | 23·0 ± 1·86 | 3·3 ± 0·06 | 35·9 ± 0·37 |

| Azolla filiculoides Lam. | Lemniden | 0·9 ± 0·14 | 0·08 ± 0 .02 | 0·02 ± 0·00 | 29·5 ± 7·26 | 41·4 ± 11·76 | 3·5 ± 0·03 | 35·4 ± 0·16 |

| Berula erecta (Huds.) Coville | Herbiden | 1112·4 ± 260·61 | 153·92 ± 38·70 | 17·64 ± 4·58 | 11·5 ± 0·62 | 63·5 ± 4·61 | 4·0 ± 0·03 | 37·2 ± 0·24 |

| Callitriche obtusangula LeGall | Pepliden | 26·8 ± 2·42 | 3·57 ± 0·36 | 0·34 ± 0·03 | 9·4 ± 0·38 | 79·8 ± 5·45 | 4·7 ± 0·19 | 41·2 ± 0·21 |

| Callitriche platycarpa Kütz. | Pepliden | 32·0 ± 4·63 | 3·70 ± 0·54 | 0·48 ± 0·11 | 12·8 ± 1·19 | 68·5 ± 8·65 | 2·8 ± 0·01 | 37·4 ± 0·07 |

| Ceratophyllum demersum L. | Ceratophylliden | 41·1 ± 8·46 | 9·49 ± 1·96 | 0·66 ± 0·13 | 7·1 ± 0·43 | 61·5 ± 5·15 | 4·2 ± 0·05 | 39·9 ± 0·20 |

| Egeria densa Planch. | Elodeiden | 104·0 ± 13·90 | 7·98 ± 1·14 | 1·13 ± 0·20 | 14·1 ± 0·63 | 92·6 ± 6·92 | 5·1 ± 0·05 | 42·9 ± 0·26 |

| Elodea canadensis Michx. | Elodeiden | 26·3 ± 3·71 | 2·02 ± 0·31 | 0·35 ± 0·06 | 17·5 ± 2·92 | 76·4 ± 14·29 | 4·5 ± 0·07 | 39·2 ± 0·60 |

| Elodea nuttallii (Planch.) H.St.John | Elodeiden | 27·7 ± 4·26 | 2·03 ± 0·49 | 0·46 ± 0·12 | 22·5 ± 1·45 | 62·3 ± 8·10 | 3·3 ± 0·11 | 37·8 ± 0·74 |

| Groenlandia densa (L.) Fourr. | Parvopotamiden | 39·9 ± 8·06 | 2·07 ± 0·45 | 0·36 ± 0·09 | 17·3 ± 1·51 | 112·1 ± 9·22 | 3·1 ± 0·07 | 38·5 ± 0·33 |

| Helosciadium nodiflorum (L.) W.D.J. Koch | Herbiden | 3362·4 ± 974·29 | 717·73 ± 235·11 | 56·58 ± 18·00 | 7·9 ± 0·58 | 60·2 ± 7·50 | 5·0 ± 0·01 | 39·1 ± 0·10 |

| Hippuris vulgaris L. | Elodeiden | 52·3 ± 8·10 | 5·73 ± 1·05 | 0·72 ± 0·15 | 12·5 ± 0·88 | 73·7 ± 5·84 | 3·4 ± 0·03 | 38·2 ± 0·13 |

| Hottonia palustris L. | Myriophylliden | 257·7 ± 11·40 | 31·02 ± 1·80 | 5·82 ± 1·24 | 18·7 ± 3·74 | 45·9 ± 8·64 | 2·0 ± 0·06 | 41·2 ± 0·53 |

| Hydrocharis morsus-ranae L. | Hydrochariden | 1466·6 ± 170·53 | 283·93 ± 42·79 | 41·49 ± 6·20 | 14·6 ± 0·38 | 35·5 ± 1·93 | 4·1 ± 0·05 | 44·0 ± 0·15 |

| Juncus bulbosus L. | Isoetiden | 91·6 ± 17·71 | 15·64 ± 4·52 | 4·07 ± 1·19 | 26·5 ± 6·54 | 23·5 ± 4·94 | 1·4 ± 0·02 | 43·3 ± 0·37 |

| Lagarosiphon major (Ridl.) Moss. | Parvopotamiden | 17·6 ± 2·69 | 1·56 ± 0·24 | 0·38 ± 0·06 | 24·4 ± 0·84 | 46·2 ± 2·24 | 3·0 ± 0·04 | 40·6 ± 0·10 |

| Lemna gibba L. | Lemniden | 18·8 ± 2·09 | 8·27 ± 1·13 | 0·34 ± 0·08 | 4·1 ± 0·96 | 56·9 ± 6·85 | 3·7 ± 0·03 | 41·6 ± 0·24 |

| Lemna minor L. | Lemniden | 5·8 ± 0·77 | 0·60 ± 0·10 | 0·07 ± 0·01 | 12·3 ± 1·02 | 80·0 ± 8·37 | 2·8 ± 0·01 | 37·4 ± 0·19 |

| Lemna minuta Kunth | Lemniden | 2·4 ± 0·54 | 0·16 ± 0·04 | 0·02 ± 0·00 | 10·1 ± 0·90 | 155·5 ± 30·07 | 2·7 ± 0·01 | 35·3 ± 0·05 |

| Lemna trisulca L. | Riccielliden | 18·0 ± 3·95 | 2·51 ± 0·48 | 0·33 ± 0·08 | 13·3 ± 2·22 | 55·0 ± 8·58 | 2·7 ± 0·03 | 36·9 ± 0·36 |

| Marsilea quadrifolia L. | Magnonymphaeiden | 534·2 ± 123·93 | 70·72 ± 17·84 | 16·01 ± 3·76 | 22·7 ± 1·27 | 33·5 ± 1·74 | 3·2 ± 0·05 | 44·3 ± 0·12 |

| Myriophyllum aquaticum (Velloso) Verdc. | Myriophylliden | 455·1 ± 57·73 | 32·79 ± 3·22 | 2·24 ± 0·27 | 6·8 ± 0·33 | 203·2 ± 11·52 | 3·0 ± 0·02 | 38·4 ± 0·10 |

| Myriophyllum spicatum L. | Myriophylliden | 160·0 ± 56·09 | 18·45 ± 5·76 | 2·22 ± 0·70 | 12·1 ± 0·97 | 71·4 ± 6·87 | 3·3 ± 0·00 | 42·1 ± 0·11 |

| Myriophyllum verticillatum L. | Myriophylliden | 278·3 ± 58·21 | 38·68 ± 10·56 | 2·96 ± 0·83 | 7·6 ± 0·47 | 96·5 ± 12·54 | 2·7 ± 0·02 | 41·2 ± 0·20 |

| Najas marina ssp. intermedia (Wolfg. ex Gorski) Casper | Parvopotamiden | 94·3 ± 18·93 | 50·58 ± 14·10 | 2·43 ± 0·63 | 4·8 ± 0·30 | 39·8 ± 5·11 | 2·4 ± 0·06 | 36·2 ± 0·49 |

| Najas minor All. | Parvopotamiden | 6·2 ± 1·29 | 0·69 ± 0·15 | 0·08 ± 0·02 | 12·1 ± 1·61 | 76·3 ± 16·21 | 3·7 ± 0·08 | 40·9 ± 0·52 |

| Nasturtium officinale R.Br. subsp. officinale | Herbiden | 339·3 ± 160·47 | 56·39 ± 29·70 | 3·48 ± 1·82 | 6·2 ± 0·50 | 101·0 ± 12·97 | 6·7 ± 0·08 | 39·2 ± 0·22 |

| Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. | Magnonymphaeiden | 27701·7 ± 4930·16 | 13464·90 ± 2803·01 | 2688·60 ± 559·88 | 20·0 ± 1·52 | 10·4 ± 0·98 | 2·7 ± 0·03 | 44·8 ± 0·22 |

| Nymphaea alba L. | Magnonymphaeiden | 44608·0 ± 6206·08 | 23801·20 ± 3389·24 | 4980·90 ± 894·25 | 20·8 ± 0·97 | 9·0 ± 0·58 | 1·9 ± 0·02 | 45·2 ± 0·08 |

| Nymphaea candida C. Presl | Magnonymphaeiden | 35576·6 ± 6193·01 | 14390·00 ± 3148·49 | 2998·00 ± 878·03 | 20·6 ± 2·32 | 12·3 ± 2·09 | 3·1 ± 0·04 | 45·4 ± 0·20 |

| Nymphaea odorata subsp. tuberosa (Paine) Wiersema & Hellquist | Magnonymphaeiden | 25388·1 ± 5011·12 | 11098·00 ± 2652·61 | 2053·00 ± 419·81 | 18·7 ± 2·12 | 12·5 ± 1·86 | 2·8 ± 0·03 | 45·4 ± 0·16 |

| Nymphaea × marliacea Wildsmith cv. Carnea | Magnonymphaeiden | 43936·7 ± 8548·06 | 18817·80 ± 4797·76 | 3309·90 ± 1111·52 | 17·4 ± 3·27 | 13·9 ± 2·20 | 2·4 ± 0·02 | 45·2 ± 0·14 |

| Nymphoides peltata (S.G. Gmel.) Kuntze | Magnonymphaeiden | 6894·3 ± 021·33 | 2243·07 ± 694·13 | 268·04 ± 86·74 | 11·9 ± 0·78 | 26·1 ± 3·19 | 2·8 ± 0·01 | 44·6 ± 0·10 |

| Persicaria amphibia (L.) Delarbre | Magnonymphaeiden | 1347·6 ± 198·90 | 242·48 ±3 7·41 | 44·24 ± 8·14 | 18·2 ± 1·03 | 30·7 ± 2·30 | 3·9 ± 0·05 | 45·0 ± 0·34 |

| Persicaria dubia (Stein.) Fourr. | Herbiden | 821·9 ± 58·78 | 131·87 ± 9·81 | 14·98 ± 0·89 | 11·4 ± 0·46 | 54·9 ± 2·71 | 5·6 ± 0·06 | 41·2 ± 0·39 |

| Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre | Herbiden | 1017·0 ± 346·47 | 100·42 ± 33·24 | 12·33 ± 3·64 | 12·4 ± 0·77 | 81·5 ± 6·84 | 5·4 ± 0·12 | 42·8 ± 0·43 |

| Potamogeton berchtoldii Fieber | Parvopotamiden | 60·5 ± 6·88 | 3·51 ± 0·43 | 0·63 ± 0·13 | 17·9 ± 2·57 | 98·3 ± 14·89 | 3·5 ± 0·07 | 39·1 ± 0·46 |

| Potamogeton crispus L. | Parvopotamiden | 499·9 ± 39·12 | 56·05 ± 4·73 | 11·08 ± 0·83 | 19·9 ± 1·88 | 45·3 ± 4·80 | 4·2 ± 0·02 | 45·2 ± 0·34 |

| Potamogeton lucens L. | Batrachiden | 1686·2 ± 220·79 | 329·95 ± 45·08 | 40·92 ± 5·33 | 12·4 ± 0·45 | 41·3 ± 1·91 | 4·7 ± 0·05 | 42·5 ± 0·08 |

| Potamogeton natans L. | Batrachiden | 3736·9 ± 754·83 | 644·56 ± 140·91 | 119·66 ± 26·34 | 18·6 ± 1·52 | 31·7 ± 5·06 | 4·1 ± 0·09 | 44·6 ± 0·14 |

| Potamogeton nodosus Poir. | Batrachiden | 4068·4 ± 702·53 | 932·10 ± 200·07 | 183·67 ± 62·22 | 19·6 ± 4·82 | 24·2 ± 8·30 | 3·5 ± 0·06 | 45·2 ± 0·18 |

| Potamogeton pectinatus L. | Parvopotamiden | 40·4 ± 6·63 | 8·65 ± 1·68 | 1·22 ± 0·23 | 14·1 ± 0·89 | 33·8 ± 6·03 | 3·7 ± 0·14 | 43·8 ± 1·20 |

| Potamogeton perfoliatus L. | Magnopotamiden | 654·4 ± 137·03 | 99·96 ± 22·78 | 16·26 ± 3·25 | 16·4 ± 0·99 | 40·2 ± 2·98 | 2·4 ± 0·06 | 40·9 ± 0·18 |

| Potamogeton polygonifolius Pourr. | Batrachiden | 1529·0 ± 229·32 | 309·36 ± 55·52 | 102·31 ± 15·13 | 33·3 ± 1·78 | 15·0 ± 1·07 | 2·3 ± 0·04 | 45·0 ± 0·55 |

| Potamogeton trichoides Cham. & Schltdl. | Parvopotamiden | 24·4 ± 5·01 | 1·39 ± 0·32 | 0·31 ± 0·07 | 22·1 ± 1·75 | 80·2 ± 5·68 | 4·6 ± 0·11 | 41·5 ± 0·59 |

| Ranunculus aquatilis L. | Batrachiden | 169·5 ± 31·35 | 37·76 ± 8·20 | 4·02 ± 0·81 | 10·7 ± 0·33 | 42·4 ± 2·21 | 5·3 ± 0·04 | 41·9 ± 0·25 |

| Ranunculus fluitans Lam. | Myriophylliden | 638·8 ± 118·09 | 195·71 ± 42·38 | 26·08 ± 6·84 | 13·2 ± 1·25 | 25·2 ± 3·54 | 3·1 ± 0·02 | 42·1 ± 0·47 |

| Ranunculus trichophyllus Chaix subsp. eradicatus (Laest.) C.D.K. Cook | Myriophylliden | 107·0 ± 48·97 | 14·89 ± 7·00 | 2·85 ± 0·93 | 20·5 ± 5·18 | 36·7 ± 7·73 | 3·0 ± 0·08 | 44·1 ± 0·11 |

| Ranunculus trichophyllus Chaix subsp. trichophyllus | Myriophylliden | 974·3 ± 180·00 | 226·01 ± 48·03 | 20·31 ± 4·36 | 9·0 ± 1·08 | 48·3 ± 3·98 | 4·2 ± 0·13 | 41·3 ± 0·31 |

| Salvinia natans (L.) All. | Lemniden | 126·5 ± 18·01 | 31·74 ± 6·40 | 2·29 ± 0·52 | 7·2 ± 0·71 | 56·7 ± 8·77 | 3·1 ± 0·04 | 39·0 ± 0·40 |

| Sparganium emersum Rehmann | Vallisneriden | 5247·5 ± 1757·44 | 1324·50 ± 578·09 | 125·69 ± 49·29 | 9·6 ± 0·99 | 42·5 ± 3·60 | 3·7 ± 0·03 | 41·3 ± 0·24 |

| Sparganium natans L. | Vallisneriden | 3042·4 ± 302·53 | 677·27 ± 88·03 | 141·49 ± 13·69 | 21·0 ± 1·43 | 21·6 ± 1·73 | 3·7 ± 0·02 | 45·4 ± 0·04 |

| Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) Schleid. | Lemniden | 40·0 ± 2·53 | 8·59 ± 0·73 | 0·94 ± 0·08 | 11·0 ± 0·75 | 42·7 ± 3·30 | 4·7 ± 0·05 | 42·1 ± 0·28 |

| Trapa natans L. | Magnonymphaeiden | 3640·7 ± 467·05 | 1430·81 ± 199·74 | 319·35 ± 46·73 | 22·3 ± 1·17 | 11·4 ± 0·63 | 2·8 ± 0·01 | 42·5 ± 0·04 |

| Utricularia australis R.Br. | Ceratophylliden | 106·5 ± 12·48 | 10·21 ± 1·95 | 0·82 ± 0·16 | 8·0 ± 0·36 | 133·3 ± 19·57 | 4·0 ± 0·06 | 44·3 ± 0·29 |

| Utricularia vulgaris L. | Ceratophylliden | 46·3 ± 11·62 | 3·49 ± 0·84 | 0·28 ± 0·07 | 8·1 ± 0·59 | 164·0 ± 9·31 | 3·5 ± 0·11 | 39·8 ± 0·80 |

| Vallisneria americana Michx. | Vallisneriden | 21861·6 ± 4590·41 | 8990·60 ± 1991·34 | 509·17 ± 153·22 | 5·6 ± 0·60 | 43·9 ± 4·64 | 2·8 ± 0·02 | 37·7 ± 0·11 |

| Vallisneria spiralis L. | Vallisneriden | 4095·9 ± 1062·65 | 1080·80 ± 325·96 | 62·13 ± 21·34 | 5·7 ± 0·39 | 68·1 ± 8·82 | 3·5 ± 0·01 | 35·6 ± 0·09 |

| Veronica beccabunga L. | Herbiden | 280·9 ± 63·58 | 44·36 ± 11·17 | 2·36 ± 0·60 | 5·3 ± 0·19 | 120·1 ± 6·08 | 5·0 ± 0·01 | 42·5 ± 0·05 |

| Wolffia arrhiza (L.) Horkel ex Wimm. | Lemniden | 0·8 ± 0·09 | 0·19 ± 0·04 | 0·01 ± 0·00 | 4·4 ± 0·73 | 103·4 ± 25·81 | 4·3 ± 0·08 | 36·6 ± 0·55 |

| Zannichellia palustris L. subsp. palustris | Parvopotamiden | 19·3 ± 3·60 | 1·73 ± 0·39 | 0·23 ± 0·04 | 13·2 ± 0·83 | 85·6 ± 8·66 | 2·8 ± 0·04 | 36·8 ± 0·17 |

Data represent the means ± s.e. of ten replicates (LNC and LCC; n = 3). Traits are: LA, leaf area; LFW, leaf fresh weight; LDW, leaf dry weight; LDMC, leaf dry matter content; SLA, specific leaf area; LNC, leaf nitrogen concentration; LCC, leaf carbon concentration. Growth forms follow Wiegleb (1991), as summarized in Table 1.

The most distal fully expanded leaves along the rhizome or stem were sampled. For the special case of the carnivorous Utricularia species, the area of the distal 4 cm of each shoot (including photosynthetic stems and stem-like leaves) were sampled and bladder traps were removed prior to area and mass measurements. Plant material was transported to the laboratory and stored underwater in the dark overnight at 4 °C. Following the standardized methods of Cornelissen et al. (2003), turgid leaf fresh weight (LFW) was determined from these saturated organs. Leaf area was determined using a digital leaf area meter (Delta-T Image Analysis System; Delta-T Devices Co. Ltd, Burwell, Cambridgeshire, UK). Leaf dry weight (LDW) was then determined following drying for 24 h at 105 °C, and parameters such as SLA [i.e. leaf area (LA) divided by LDW] were calculated. Leaf dry matter content (LDMC) was calculated as the proportion of LFW accounted for by LDW. Leaf nitrogen concentration (LNC) and leaf carbon concentration (LCC) were quantified from dried plant material using a CHN-analyzer [NA-2000 NProtein; Fisons Instruments S.p.A., Rodano (MI), Italy] following the method outlined by Cerabolini et al. (2010a).

Data gathered for aquatic species were compared against data, measured using precisely the same methods, for terrestrial herbaceous species already published in the FIFTH database (the Flora d'Italia Functional Traits Hoard; Cerabolini et al. 2010a), downloadable from: www.springerlink.com/content/21535l25m82×7076/supplementals.

The FIFTH database includes 506 terrestrial species from geo-climatically diverse regions of northern Italy (from lowland, mid-elevation and alpine sites), and encompasses the full range of leaf economics values so far recorded for herbaceous species, providing an appropriate and readily available ‘control’ spectrum against which to compare the leaf traits of hydrophytes measured from the same latitudes (Cerabolini et al., 2010a). The FIFTH database also includes whole-plant traits and CSR strategies for each species, the latter calculated following the method of Hodgson et al. (1999) and which we have described and justified extensively in previous publications (Caccianiga et al., 2006; Pierce et al., 2007a, b; Cerabolini et al., 2010a, b). The ‘GLOPNET leaf economics dataset’ available as part of the publication of Wright et al. (2004) has a wider coverage, in terms of the number of species and geographic range, but does not include CSR strategies, or basic leaf size traits such as area or mass (only transformed values of traits derived from these measurements, such as logLMA, are available).

For each trait, data were normalized and the spectrum of mean values was compared between aquatic and terrestrial species using Student's t-test. Normalization of percentage data was carried out by arcsine transformation (for the traits LDMC, LNC and LCC), and logarithmic transformation was used for LA, LFW, LDW and SLA. Co-variation between traits was determined from non-normalized data using principal components analysis (PCA; Multi-Variate Statistical Package v3·13o; Kovach computing Services, Anglesey, UK). Data were also compared between aquatic plant growth forms, sensu Wiegleb (1991).

RESULTS

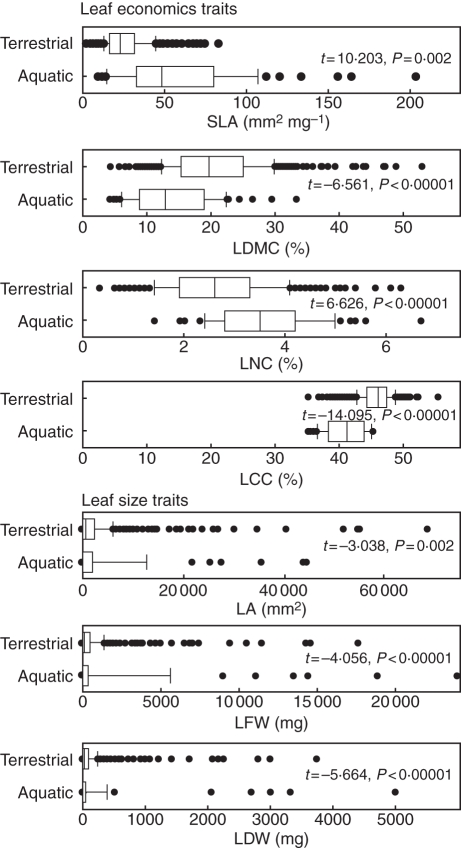

Trait means for the 61 species are presented in Table 2 (a version of this table in Microsoft Excel format including values for the 506 terrestrial species is available as Supplementary Data Table S1). Hydrophytes exhibited significantly greater mean SLA and LNC than terrestrial species, and significantly lower mean LDMC, LCC, LA, LFW and LDW (Fig. 1). Specifically, a mean SLA of 59·6 ± 5·1 mm2 mg−1 for hydrophytes was significantly greater (P < 0·0001) than the 26·0 ± 0·6 mm2 mg−1 mean of terrestrial species, and hydrophyte SLA values ranged from a moderately low 9·0 ± 0·58 mm2 mg−1 in Nymphaea alba to the extremely fine and soft leaves of Myriophyllum aquaticum (203·2 ± 11·52 mm2 mg−1; Fig. 1). Hydrophytes included much higher SLA values and a greater overall SLA compared with terrestrial species (Fig. 1). Mean LNC was 3·6 % for hydrophytes vs. 2·7 % for terrestrial plants; LCC, 41·1 % (hydrophytes) vs. 46·0 % (terrestrial); LDMC, 14·2 % (hydrophytes) vs. 20·7 % (terrestrial) – all statistically different at the P ≤ 0·001 level (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of leaf economics traits (LCC, leaf carbon concentration; LDMC, leaf dry matter content; LNC, leaf nitrogen concentration; SLA, specific leaf area) and leaf size traits (LA, leaf area; LDW, leaf dry weight; LFW, leaf fresh weight) between terrestrial herbs (n = 506) and aquatic species (n = 61). Data represent the mean of ten replicates, and means of the two groups are compared by Student's t-test, following normalization for each trait as detailed in the text.

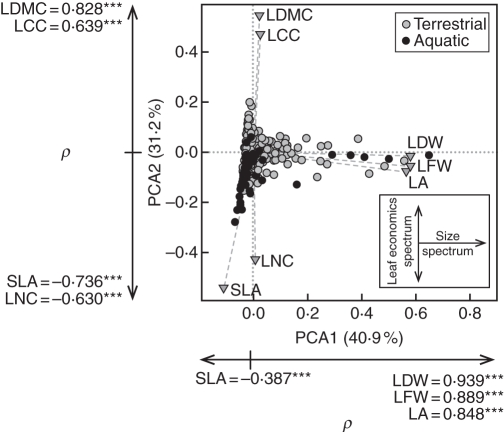

The first two axes of the PCA accounted for 72·1 % of the total variability in the data (Fig. 2) and included: PCA1, an axis of variability in size-related traits, such as LA, LFW and LDW; and PCA2, an axis of leaf economics running from high LMDC and LCC at one extreme to high SLA and LNC at the other extreme. Traits were highly significantly correlated with PCA scores as determined by Spearman's correlation coefficient (Fig. 2). Most hydrophytes were ordinated within the same triangle of multidimensional space occupied by terrestrial species, but nine species with particularly high SLA, high LNC leaves extended the triangle negatively along the PCA2 axis (Helosciadium nodiflorum, Lemna minuta, Myriophyllum aquaticum, Nasturtium officinale, Utricularia australis, U. vulgaris, Vallisneria spiralis, Veronica beccabunga and Wolffia arrhiza). No hydrophytes exhibited high LMDC and LCC equivalent to terrestrial species at the positive extreme of PCA2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Principal components analysis (PCA) biplot showing the first two principal axes of variation in mean leaf trait data for 506 herbaceous (grey circles) and 61 aquatic (black circles) plant species from alpine, sub-alpine and lowland continent bioclimatic zones of northern Italy. PCA axis 1 and axis 2 together account for 72·1 % of variability in the data set. Significant correlations between trait scores and PCA axes were determined using Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ), where *** denotes a significant correlation at the P ≤ 0·001 level. Traits are: LA, leaf area; LCC, leaf carbon content; LDW, leaf dry weight; LDMC, leaf dry matter content; LFW, leaf fresh weight; LNC, leaf nitrogen content; SLA, specific leaf area.

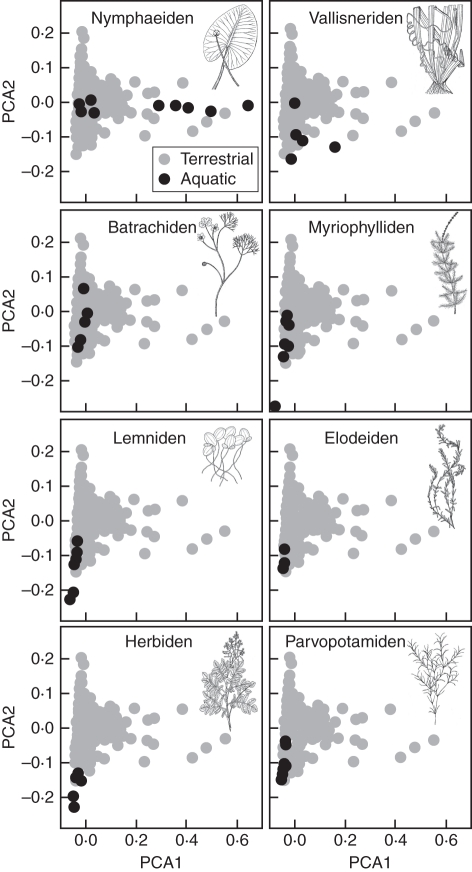

Differences were evident between growth forms. Most growth forms were comprised of species with small, high SLA, high LNC leaves, and some growth forms were restricted to this suite of traits (e.g. Elodeiden, Herbiden, Lemniden and Parvopotamiden) (Fig. 3). However, the Batrachiden spanned a range of moderate leaf economics trait values, all with small leaves, and the Nymphaeiden all exhibited intermediate leaf economics trait values but encompassed the full variation in leaf size evident for terrestrial herbs (Fig. 3). Growth forms represented by only one or two species are presented, not in Fig. 3, but together in Supplementary Data Fig. S1.

Fig. 3.

A comparison of the PCA ordinations of eight of the most frequently represented hydrophyte growth forms (black circles) within the context of terrestrial herbaceous plant trait variation (grey circles). Line drawings are copyright-free material made available by the USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov), originally by Britton and Brown (1913).

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that there is nothing fundamentally different about the adaptive trade-offs faced by hydrophytes and terrestrial plants. Firstly, with regard to plant economics, most hydrophytes simply lie at one extreme of the acquisitive/conservative economics spectrum. Indeed, hydrophytes exhibit the lowest LMA values ever recorded (Poorter et al., 2009): Gerber and Les (1994) determined a value of 3 g m−2 within the genus Myriophyllum, and in the present study a value of 4·9 g m−2 (when converted from SLA) was recorded for Myriophyllum aquaticum. The low LMA/high SLA leaves of most hydrophytes act to minimize resistances to the diffusion of resources (particularly CO2) between the environment and the chloroplasts, and are thus highly acquisitive, thin (including thin cuticles) and may orient chloroplasts towards the epidermis to maximize photosynthetic rates (Mommer et al., 2004, 2005a, b; Voesenek et al., 2006). Indeed, there is now evidence that many of the characteristics of hydrophytes, particularly those with emergent leaves that must acclimate to flooding, may simply be co-opted from the responses typical of terrestrial plants: low LMA may be a response to low photosynthate concentrations, and a thin cuticle a response to high humidity (Mommer et al., 2007). Thus we can have a high degree of confidence in the statement that hydrophytes extend the leaf economics spectrum to include the most acquisitive leaves so far measured.

However, our data also demonstrate that not all hydrophytes lie at the acquisitive extreme of the leaf economics spectrum, and not all share the same adaptive strategy. When the principal directions of adaptive specialization were examined by PCA (Fig. 2) we found that many hydrophyte growth forms, particularly Elodeiden, Herbiden, Lemniden, Myriophylliden and Parvopotamiden, achieved a position in the PCA also occupied by highly ruderal, R-selected herbaceous terrestrial plants. Cerabolini et al. (2010a) provide precise CSR co-ordinates for the terrestrial species, so we can be certain of the classification of these hydrophytes as R selected. In fact, nine species of Herbiden and Lemniden (listed previously in the Results section) went beyond the degree of R selection evident for the most ruderal of terrestrial species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, Poa annua and Stellaria media. Thus many aquatic species are R selected in the extreme, in keeping with a lifestyle based around rapid regeneration in the face of disturbance. Many are typical of disturbed habitats, colonizing where seasonal flooding scours away vegetation (e.g. Nasturtium officinale and Zannichellia palustris; Bornette et al., 2008) and some, such as Potamogeton pectinatus, germinate after scouring events due to natural scarification of the seeds (Teltscherova and Hejny, 1973). Hippuris vulgaris, Myriophyllum spicatum and Alisma species have seeds that can float for extended periods, sometimes for more than a year, to allow colonization of fresh sites (Guppy, 1906; Praeger, 1913).

In contrast, species such as Nuphar lutea and Nymphaea alba (Nymphaeiden) exhibit a range of traits suggesting a different adaptive strategy based on the evolution of size variation (Fig. 3) and differing competitive ability between species. Other traits that may form part of this C-selected syndrome for Nymphaeiden include moderate relative growth rates, limited vegetative dispersal and seeds that sink immediately, with strict light/water quality requirements for germination (Bornette et al., 2008). Indeed, it is evident from Fig. 3 that the Nymphaeiden encompass a spectrum of strategies equivalent to highly C-selected to SR-selected terrestrial species, such as Pteridium aquilinum, Aruncus dioicus, Filipendula ulmaria and Laserpitium halleri (C selected), and Hieracium glaciale, Lotus alpinus and Gentiana brachyphylla (SR selected; Cerabolini et al., 2010a).

The most S-selected hydrophytes were Juncus bulbosus (Isoetiden), Potamogeton polygonifolius (Batrachiden) and Trapa natans (Magnonymphaeiden), although in absolute terms these were SR selected, occupying positions on the PCA plot that overlapped with terrestrial SR-selected species such as Aira caryophyllea. Thus no hydrophyte species in our study exhibited the extremely conservative leaf economics typical of S-selected species in low productivity terrestrial habitats, such as Erica carnea and Carex curvula from the positive extreme of PCA2 (Fig. 2). This confirms Kautsky's (1988) suggestion that hydrophytes may not include stress tolerators sensu Grime (1979).

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that together the leaf economics spectrum and leaf size traits provide a dependable common reference frame for the quantitative comparison of the wider primary adaptive strategies of plants from highly contrasting habitats.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

S.P. and G.B. were funded by the Native Flora Centre of the Lombardy Region (Centro Flora Autoctona; CFA) via the University of Insubria.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bornette G, Tabacchi E, Hupp C, Puijalon S, Rostan JC. A model of plant strategies in fluvial hydrosystems. Freshwater Biology. 2008;53:1692–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Britton NL, Brown A. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons; 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Caccianiga M, Luzzaro A, Pierce S, Ceriani RM, Cerabolini B. The functional basis of a primary succession resolved by CSR classification. Oikos. 2006;112:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cerabolini BEL, Brusa G, Ceriani RM, De Andreis R, Luzzaro A, Pierce S. Can CSR classification be generally applied outside Britain? Plant Ecology. 2010a;210:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Cerabolini B, Pierce S, Luzzaro A, Ossola A. Species evenness affects ecosystem processes in situ via diversity in the adaptive strategies of dominant species. Plant Ecology. 2010b;207:333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen JHC, Lavorel S, Garnier E, et al. A handbook of protocols for standardised and easy measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany. 2003;51:335–380. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Hodgson JG, Thompson K, et al. The plant traits that drive ecosystems: evidence from three continents. Journal of Vegetation Science. 2004;15:295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Freschet GT, Cornelissen JHC, van Logtestijn RSP, Aerts R. Evidence of the ‘plant economics spectum’ in a subarctic flora. Journal of Ecology. 2010;98:362–373. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber DT, Les DH. Comparison of leaf morphology among submersed species of Myriophyllum (Haloragaceae) from different habitats and geographical distributions. American Journal of Botany. 1994;81:973–979. [Google Scholar]

- Greulich S, Bornette G. Competitive abilities and related strategies in four aquatic plant species from an intermediately disturbed habitat. Freshwater Biology. 1999;41:493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. Plant strategies, vegetation processes, and ecosystem properties. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. Plant strategies, vegetation processes, and ecosystem properties. 2nd edn. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, Pierce S. The evolutionary strategies that shape ecosystems. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, Thompson K, Hunt R, et al. Integrated screening validates primary axes of specialisation in plants. Oikos. 1997;79:259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, Hodgson JG, Hunt R. Comparative plant ecology: a functional approach to common British species. 2nd edn. London: Unwin Hyman; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guppy HB. Observations of a naturalist in the Pacific between 1896 and 1899. New York: The Macmillan Company; 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson JG, Wilson PJ, Hunt R, Grime JP, Thompson K. Allocating CSR plant functional types: a soft approach to a hard problem. Oikos. 1999;83:282–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kautsky L. Life strategies of aquatic soft bottom macrophytes. Oikos. 1988;53:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kilinç M, Karavin N, Kutbay HG. Classification of some plant species according to Grime's strategies in a Quercus cerris L. var. cerris woodland in Samsun, northern Turkey. Turkish Journal of Botany. 2010;34:521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A, Castella E, Lachavanne J-B. Morphological traits and spatial heterogeneity of aquatic plants along sediment and depth gradients, Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Aquatic Botany. 1997;55:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Massant W, Godefroid S, Koedam N. Clustering of plant life strategies on meso-scale. Plant Ecology. 2009;205:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mommer L, Pedersen O, Visser EJW. Acclimation of a terrestrial plant to submergence facilitates gas exchange underwater. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2004;17:1281–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Mommer L, de Kroon H, Pierik R, Bögemann GM, Visser EJW. A functional comparison of acclimation to shade and submergence in two terrestrial plant species. New Phytologist. 2005a;167:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mommer L, Pons TL, Wolters-Arts M, Venema JH, Visser EJW. Submergence-induced morphological, anatomical and biochemical responses in a terrestrial species affect gas diffusion resistance and photosynthetic performance. Plant Physiology. 2005b;139:497–508. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.064725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mommer L, Wolters-Arts M, Andersen C, Visser EJW, Pedersen O. Submergence-induced leaf acclimation in terrestrial species varying in flooding tolerance. New Phytologist. 2007;176:337–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KJ, Rørslett B, Springuel I. Strategy analysis of submerged lake macrophyte communities: an international example. Aquatic Botany. 1990;36:303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Navas M-L, Roumet C, Bellmann A, Laurent G, Garnier E. Suites of plant traits in species from different stages of a Mediterranean secondary succession. Plant Biology. 2010;12:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S, Ceriani RM, De Andreis R, Cerabolini B. The leaf economics spectrum of Poaceae reflects variation in survival strategies. Plant Biosystems. 2007a;141:337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S, Luzzaro A, Caccianiga M, Ceriani RM, Cerabolini B. Disturbance is the principal α-scale filter determining niche differentiation, coexistence and biodiversity in an alpine community. Journal of Ecology. 2007b;95:698–706. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti S. Flora d'Italia. Bologna: Edagricole (in Italian); 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Niinemets Ü, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Villar R. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New Phytologist. 2009;182:565–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praeger RL. On the buoyancy of seeds of some Britannic plants. Proceedings of the Royal Dublin Society. 1913;14:13–62. [Google Scholar]

- Simonová D, Lososová Z. Which factors determine plant invasions in man-made habitats in the Czech Republic? Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 2008;10:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Teltscherova L, Hejny S. The germination of some Potamogeton species from South-Bohemia in fishponds. Folia Geobotanica Phytotaxonomica, Praha. 1973;8:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Voesenek LACJ, Colmer TD, Pierik R, Millenaar FF, Peeters AJM. How plants cope with complete submergence. Tansley Review. New Phytologist. 2006;170:213–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiher E, van der Werf A, Thompson K, Roderick M, Garnier E, Eriksson O. Challenging Theophrastus: a common core list of plant traits for functional ecology. Journal of Vegetation Science. 1999;10:609–620. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegleb G. Lebens – und Wuchsformen der makrophytischen Wasserpflanzen und deren Beziehungen zur Ökologie, Verbreitung und Vergesellschaftung der Arten. Tuexenia. 1991;11:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature. 2004;428:821–827. doi: 10.1038/nature02403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.