Abstract

We used viral metagenomics to identify a novel parvovirus in tissues of a gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). Nearly full genome characterization and phylogenetic analyses showed this parvovirus (provisionally named gray fox amdovirus) to be distantly related to Aleutian mink disease virus, representing the second viral species in the Amdovirus genus.

Keywords: viruses, amdovirus, Aleutian mink disease virus, parvovirus, gray fox, dispatch

Aleutian mink disease virus (AMDV) is currently the only member of the genus Amdovirus in the family Parvoviridae; it can infect diverse breeds of farmed and feral mink, in addition to other mustelids (e.g., ferrets, otters), raccoons, and foxes (1,2). AMDV has an ≈5-kb single-stranded DNA genome and, like other parvoviruses, replicates through a rolling-hairpin mechanism (3). The viral genome has 2 large open reading frames (ORFs), encoding nonstructural (NS1, NS2, putative NS3) and structural viral proteins (VP1 and VP2). Alternative splicing enables expression of multiple messenger RNAs (4). AMDV strains can exhibit sequence variability in their NS gene, and 3 genetic groups have been identified on the basis of partial nucleotide sequences of this region (5).

AMDV infection can cause an acute and fatal interstitial pneumonia in newborn mink. It can also cause a chronic disorder of the immune system in adult mink, characterized by persistent viral infection, plasmacytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia, and immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis and arteritis, resulting in major economic losses to mink farms (6). AMDV infection can also be asymptomatic. The different outcomes are determined by host factors that include age, immune status, and the virulence of the virus strains (7,8). AMDV can be transmitted through urine, feces, and saliva as well as vertically in utero (9,10). In 1 report, a ferret found to be naturally infected with AMDV showed acute dyspnea and posterior paresis with histopathologic lesions similar to those seen in mink; the ferret became comatose and died (11). Recently, 2 mink farmers with vascular disease and microangiopathy, similar to conditions in mink with Aleutian disease, were found to have AMDV-specific antibodies and were AMDV DNA positive, suggesting a potential relationship between AMDV and human symptoms (12).

We used random PCR amplification and high-throughput sequencing technology to investigate viral sequences found in the spleen and lung tissues of a sick gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) from California. A highly divergent amdovirus was identified, and the near full genome of this virus was obtained. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that this virus, designated as gray fox amdovirus, is a new amdovirus species, only the second for that genus.

The Study

The gray fox studied here was identified during the summer of 2009 in Sonoma County, California. It had severe gait abnormalities, lymphadenopathy, and acute muscle inflammation, and was euthanized at a wildlife rehabilitation center. Using the generic viral particle enrichment method previously described for tissues (13), we generated ≈14,000 sequence reads from spleen and lung samples. We found 136 sequence reads in spleen tissue that were related to AMDV by using BLASTx (E score <10–5) (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST); these could be assembled into 24 contigs covering ≈60% of the viral genome. By connecting gaps between sequenced viral fragments and amplifying the genome extremities by using PCR primers based on AMDV sequences, the nearly complete genome of the new amdovirus (GenBank accession no. JN202450) was acquired. We temporarily named it gray fox amdovirus (GFADV).

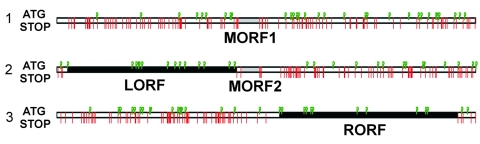

The partial GFADV genome was 4,441 nt in length with a low guanine–cytosine content of 37%. Similar to that of AMDV, the GFADV genome contained 2 major ORFs. The left ORF (LORF) contains the bulk of the sequences for the putative NS1, and the right ORF (RORF) codes for VP2 (Figure 1). Two small middle ORFs (67 and 75 aa long) with putative alternative start codons were detected in the 448-bp region between the ORFs. The theoretical proteins showed 55% and 59% aa identity with the 2 similarly located middle ORFs reported in AMDV. The partial 5′ untranslated region (UTR) was 109 nt and the partial 3′ UTR was 191 nt. Potential RNA splicing signals in AMDV were present on the GFADV genome (Technical Appendix Figure 1) (4). The predicted spliced transcripts encode hypothetical NS1, NS2, and NS3 of 635 aa, 115 aa, and 80 aa, respectively, and a capsid protein VP1 of 674 aa. The putative VP2 was predicted to arise from the intact transcript of RORF encoding a 630-aa protein.

Figure 1.

Open reading frames (ORFs) in gray fox amdovirus genome. Three possible reading frames of the plus-strand sequence with the stop codons indicated by red lines and ATG codons by green flags. Two major ORFs, left (LORF) and right (RORF), are indicated by black bars; 2 small middle ORFs (MORF1 and MORF2) are indicated by gray bars.

Sequence analyses confirmed that GFADV was a divergent amdovirus with 76% nt identity with the genome of AMDV. Conserved protein domains typical of parvoviruses were identified in GFADV. In the LORF, the GKRN domain was found (Technical Appendix Figure 2), which may act as the nuclear transport signal of NS1 protein. In the RORF, 3 conserved domains (TPW, YNN, and PIW) of unknown biologic significance were detected (6,14) (Technical Appendix Figure 3). The phosholipase 2 motif in the N terminal VP1 region, generally conserved in parvoviruses, was not found in either GFADV not AMDV (Technical Appendix Figure 3), which suggests that this parvovirus genus uses a different mechanism to escape the endosome during infection (15).

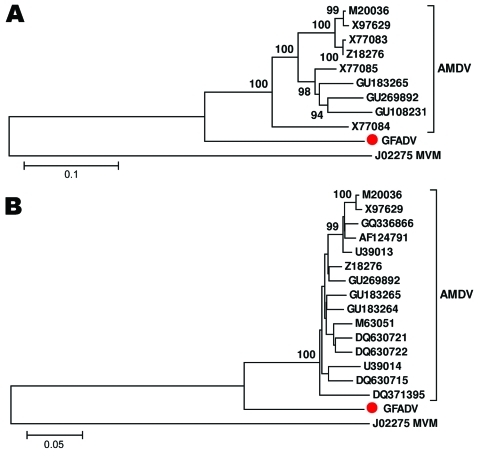

Comparison of NS1 regions showed GFADV shared ≈74% nt and 67% aa similarities with AMDV strains, whereas different strains of AMDV shared >87% nt and 82% aa similarities. Alignments of the VP2 region showed GFADV shared ≈78% nt and 80% aa similarities with AMDV strains, whereas strains of AMDV had >92% nt and 91% aa similarities (Technical Appendix Figure 4, Technical Appendix Figure 5). To determine the relationship between GFADV and AMDV strains, phylogenetic analyses of the NS1 and VP2 proteins were performed, which showed that in both genome regions GFADV was more closely related to AMDV strains than to those of minute virus of mice or other parvoviruses analyzed (data not shown), but was distinct from the 3 AMDV groups (Figure 2). Pending review by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, GFADV thus appears to be the second reported parvovirus species in the genus Amdovirus.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analyses of gray fox amdovirus (GFADV) (red dots) and Aleutian mink disease virus (AMDV) based on the complete amino acid sequence of nonstructural protein 1 region (A) and viral protein 1 region (B). The neighbor-joining method was used with p-distance and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Scale bars represent estimated phylogenetic divergence. GenBank accession numbers are shown on the tree. Minute virus of mice (MVM) was included as an outgroup.

GFADV sequences were also detected in the lung and heart tissues of the same animal by using a GFADV-specific nested PCR targeting a ≈400-bp segment of the VP2 gene, as well as in the heart tissue of another gray fox, which had the same signs, collected in Sonoma County in summer 2009. Further PCR screening of 19 tissue samples, including spleen, lung, liver, lymph node, and muscle from 9 other gray foxes with similar gait abnormalities and chronic muscle lesions, collected in 2008 (n = 2) and 2010 (n = 7) were negative by the same GFADV PCR.

Conclusions

We report the identification and nearly complete genome sequence of an amdovirus found in the spleen, lung, and heart tissues of 2 gray foxes that exhibited an abnormal gait and muscle inflammation of unknown origin. On the basis of phylogenetic analyses, we propose this virus as the prototype member of a second species in the Parvoviridae genus Amdovirus. Putative NS and VP1/VP2 gene RNA splicing sites were detected in the GFADV genome, which suggests the expression of different NS and VP proteins.

Except for the ubiquitous anellovirus, GFADV was the only eukaryotic virus found in the spleen tissue of the diseased gray fox. The same virus was also identified in the heart tissue of a second gray fox collected the same summer but was not detected in tissues of 9 other gray foxes with a similar syndrome collected in different years. It is possible that GFADV is an incidental finding unrelated to these foxes’ symptoms. The lack of detectable GFADV DNA in all gray foxes with similar symptoms may also be because different tissues were compared in some animals or because tissue collection occurred at different stage of infection. Future testing of a possible link between GFADV and additional unexplained diseases of foxes and other carnivores will be facilitated by the availability of its genome sequence.

Supplementary Material

Nucleotide sequence around the predicted RNA splicing sites in the gray fox amdovirus genome.

Acknowledgments

We extend special thanks to S. Blair and D. Ngoseck for technical assistance and to D. Duncan and D. Famini for detection and submission of the fox samples examined in this study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 HL083254 to E.D.

Biography

Dr Li is a staff scientist at the Blood Systems Research Institute, San Francisco, California. Her research interests are infectious diseases and viral discovery.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Li L, Pesavento PA, Woods L, Clifford DL, Luff J, Wang C, et al. Novel amdovirus in gray foxes. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Oct [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1710.110233

References

- 1.Mañas S, Cena JC, Ruiz-Olmo J, Palazon S, Domingo M, Wolfinbarger JB, et al. Aleutian mink disease parvovirus in wild riparian carnivores in Spain. J Wildl Dis. 2001;37:138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennick KE, Stevenson MA, Latimer KS, Ritchie BW, Gregory CR. Persistent viral shedding during asymptomatic Aleutian mink disease parvoviral infection in a ferret. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:594–7. 10.1177/104063870501700614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotmorel SF, Tattersall P. Parvovirus DNA replication. In: DePhamphilis ML, editor. DNA replication in eukaryoric cells. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. p. 799–813. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu J, Cheng F, Burger LR, Pintel D. The transcription profile of Aleutian mink disease virus in CRFK cells is generated by alternative processing of pre-mRNAs produced from a single promoter. J Virol. 2006;80:654–62. 10.1128/JVI.80.2.654-662.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knuuttila A, Uzcategui N, Kankkonen J, Vapalahti O, Kinnunen P. Molecular epidemiology of Aleutian mink disease virus in Finland. Vet Microbiol. 2009;133:229–38. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom ME, Alexandersen S, Perryman S, Lechner D, Wolfinbarger JB. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (ADV): sequence comparisons between a nonpathogenic and a pathogenic strain of ADV. J Virol. 1988;62:2903–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexandersen S, Larsen S, Aasted B, Uttenthal A, Bloom ME, Hansen M. Acute interstitial pneumonia in mink kits inoculated with defined isolates of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus. Vet Pathol. 1994;31:216–28. 10.1177/030098589403100209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oie KL, Durrant G, Wolfinbarger JB, Martin D, Costello F, Perryman S, et al. The relationship between capsid protein (VP2) sequence and pathogenicity of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (ADV): a possible role for raccoons in the transmission of ADV infections. J Virol. 1996;70:852–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorham JR, Henson JB, Crawford TB, Padgett GA. The epizootiology of Aleutian disease. Front Biol. 1976;44:135–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorham JR, Leader RW, Henson JB. The experimental transmission of a virus causing hypergammaglobulinemia in mink: sources and modes of infection. J Infect Dis. 1964;114:341–5. 10.1093/infdis/114.4.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Une Y, Wakimoto Y, Nakano Y, Konishi M, Nomura Y. Spontaneous Aleutian disease in a ferret. J Vet Med Sci. 2000;62:553–5. 10.1292/jvms.62.553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jepsen JR, d’Amore F, Baandrup U, Clausen MR, Gottschalck E, Aasted B. Aleutian mink disease virus and humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:2040–2. 10.3201/eid1512.090514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Victoria JG, Kapoor A, Dupuis K, Schnurr DP, Delwart EL. Rapid identification of known and new RNA viruses from animal tissues. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000163. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen KC, Shull BC, Moses EA, Lederman M, Stout ER, Bates RC. Complete nucleotide sequence and genome organization of bovine parvovirus. J Virol. 1986;60:1085–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zádori Z, Szelei J, Lacoste MC, Li Y, Gariepy S, Raymond P, et al. A viral phospholipase A2 is required for parvovirus infectivity. Dev Cell. 2001;1:291–302. 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00031-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nucleotide sequence around the predicted RNA splicing sites in the gray fox amdovirus genome.