Abstract

Bacterial distribution and antimicrobial drug resistance were monitored in patients with bacterial bloodstream infections in rural hospitals in Ghana. In 2001–2002 and in 2009, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi was the most prevalent pathogen. Although most S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates were chloramphenicol resistant, all isolates tested were susceptible to ciprofloxacin.

Keywords: bacteria, fever of unknown origin, FUO, bloodstream infection, bacteremia, typhoid fever, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, antibiotic resistance, antimicrobial resistance, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, Ghana, dispatch

In Africa, fever is usually a synonym for malaria. However, evidence exists that a large proportion of fever of unknown origin (FUO) can be attributed to bacterial bloodstream infections (BBSI). Although Staphylococcus aureus is the predominant cause of BBSI in industrialized countries (1), in African countries such as Ghana or Kenya, gram-negative bacteria are identified most often in BBSI (2,3). Furthermore, because of a lack of epidemiologic data, FUO in Africa is often treated sequentially, first with antimalarial drugs and then, until some years ago, with antimicrobial drugs such as chloramphenicol. This strategy has often been ineffective (4).

The Study

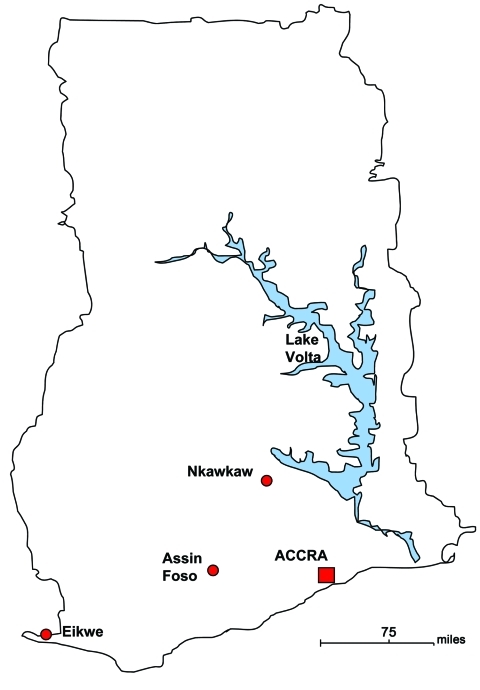

In 2000 in hospitals in Ghana, we began to establish bacteriologic laboratories, which since then have participated in a biannual quality control program. For this quality control, 3 encoded bacterial species and their resistance to various antimicrobial drugs must be correctly identified. Three of these hospitals took part in comparative epidemiologic studies of FUO during October 2001–April 2002 and again during August–September 2009 with the objective of establishing a rational treatment approach (Figure). The hospitals were located in Eikwe, a coastal village that has a rural population of ≈2,000 residents; Assin Foso, which is on a regional traffic route and has a rural/urban population of ≈15,000 residents; and Nkawkaw, which is on the national traffic route that connects Accra with Kumasi and has an urban population of >45,000 residents.

Figure.

Location of populations in a study of bacteremia and antimicrobial drug resistance over time, Ghana.

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the University Medical Center, Göttingen, Germany, and the participating hospitals in Ghana. The study design, patient selection, and diagnostic approaches were identical in both study periods; FUO was defined as fever >38.5°C of >1 week’s duration without a clear clinical or organ-specific diagnosis. During the first study period, 409 patients with a wide range of ages (interquartile range 26 years) were investigated. The second study period included 258 patients with a similar age distribution (interquartile range 27 years).

Blood film microscopy was used for malaria diagnosis. Bacteremia was determined by blood cultures; 2 mL or 5 mL of blood was incubated in 20 mL or 50 mL of locally made brain–heart infusion broth for <7 days at 37°C. Gram stains and subcultures on chocolate agar were performed after 24 h, 72 h, or when the media became turbid. Bacterial differentiation, according to good laboratory practice, and susceptibility testing by disk diffusion following National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards criteria (5) was done in Africa, and susceptibility testing that included quinolone susceptibility was confirmed by broth microdilution at the University Medical Center, Göttingen. Respective tests for species differentiation were also repeated in Göttingen. The Vi phage typing scheme from the Colindale Institute London was used for Salmonella spp. typing (6).

Of the 212 bacterial isolates recovered from the blood cultures in the first study period, 145 (68.4%) indicated a putative agent of septicemia (Table 1). Salmonella enterica was identified in 100 (69.0%) of all pathogen-positive blood cultures, with S. enterica serovar Typhi accounting for 59 (40.7%). Although the 2001 National Guidelines of Ghana listed chloramphenicol as first choice for treating typhoid fever, >80% of all bacteria identified (88.3% of all S. enteric serovar Typhi) were resistant to this drug. However, ciprofloxacin proved effective against most bacteria, especially against S. enterica serovar Typhi (Table 2). Thus, in 2004, the national guidelines replaced chloramphenicol with ciprofloxacin for treating typhoid fever (7).

Table 1. Comparative monitoring of bloodstream infections, Ghana, 2001–2002 and 2009*.

| Variable |

July 2001–April 2002 |

|

July–September 2009 |

||

| Total |

Positive for Plasmodium spp. |

|

Total |

Positive for Plasmodium spp. |

|

| No. patients with fever of unknown origin | 409 | NA | 258 | NA | |

| No. Plasmodium spp. positive/total no. tested (%)† | 85/354 (24.0) | NA | 75/177 (42.4) | NA | |

| Total no. bacterial isolates | 212 | 51 (24.1) | 99 | 14 (14.1) | |

| Skin flora contaminants | 67 | 24 (35.8) | 51 | 10 (19.6) | |

| Potential pathogens |

145 (100.0) |

27 (18.6) |

|

48 (100.0) |

4 (8.3) |

| Salmonella enterica serovars | 100 (69.0) | 20 (20.0) | 24 (50.0) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Typhi | 59 (40.7) | 11 (18.6) | 15 (31.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Paratyphi | 1 (0.7) | NF | 0 | NF | |

| Nontyphoid‡ |

40 (27.6) |

9 (22.5) |

|

9 (18.8) |

2 (22.2) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 16 (11.0) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (6.3) | NF | |

| Enterobacteriaceae other than Salmonella spp. | 10 (6.9) | 1 (10.0) | 8 (16.7) | NF | |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 7 (4.8) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (10.4) | NF | |

| Other§ | 12 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 8 (16.7) | NF | |

*Values are no. (%) except as indicated. The total number of potential pathogens for each study period was set as 100%. Coagulase-negative staphylococci, microcooci, and bacilli were judged as skin flora contaminants. The ratio of Plasmodium spp.–positive patients in regard to bacterial species respective groups is indicated. NA, not applicable; NF, Plasmodium spp. not found. †Blood film for Plasmodium spp. was done in most but not all cases. If the clinical situation, patient history, or blood count strongly indicated bacterial infection, blood culture was taken as first diagnostic approach. ‡S. enterica serovar Enteritidis and serovar Typhimurium. §Including Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Acinetobacter spp.

Table 2. Ratio in percentages of antimicrobial drug–resistant bacterial isolates obtained from patients with bacterial bloodstream infections, Ghana, 2001–2002 and 2009*.

| Bacteria type and years |

PEN |

OXA |

AMP |

CEF |

GEN |

SMX |

CMP |

CIP |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi | ||||||||

| 2001–2002 | 93.3 | 1.7 | 0 | 86.7 | 88.3 | 0 | ||

| 2009 |

|

|

100 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

100 |

0 |

| Nontyphoid Salmonella spp. | ||||||||

| 2001–2002 | 100 | 20.0 | 12.5 | 90.0 | 82.5 | 0 | ||

| 2009 |

|

|

100 |

0 |

0 |

88.9 |

77.8 |

0 |

| Enterobacteriaceae other than Salmonella spp. | ||||||||

| 2001–2002 | 100 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 0 | ||

| 2009 |

|

|

100 |

87.5 |

37.5 |

62.5 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

| Nonfermenters | ||||||||

| 2001–2002 | 91.7 | 75.0 | 16.7 | 41.7 | 100 | 0 | ||

| 2009 |

|

|

100 |

100 |

15.4 |

53.8 |

92.3 |

0 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||||||||

| 2001–2002 | 81.3 | 0 | 81.3 | 0 | 0 | 68.8 | ||

| 2009 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

|

| All bacteria | ||||||||

| 2001–2002 | 93.6 | 18.9 | 10.7 | 72.1 | 84.3 | 0 | ||

| 2009 | 100 | 41.7 | 10.4 | 72.9 | 84.4 | 8.9 |

*Blank cells indicate no testing performed. PEN, penicillin; OXA, oxacillin; AMP, ampicillin; CEF, cefuroxime; GEN, gentamicin; SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; CMP, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

To analyze the influence of ciprofloxacin on pathogen distribution and antimicrobial drug resistance in BBSI, in 2009 we initiated a follow-up study. During the second study period, pathogenic bacteria were identified in 48 (48.5%) of 99 blood cultures; the rate of Plasmodium-positive patients was significantly higher (42.4% vs. 24.0%, p<0.0001; Table 1). S. enterica was found in 50% (24/48) of all pathogen-positive blood cultures with S. enterica serovar Typhi remaining the most prevalent species (Table 1). Sampling was done during different months in the 2 study periods; however, these covered mainly the dry seasons. Although seasonal differences might have had an effect on the pathogen distribution, our finding is in accordance with results from other tropical countries (8,9). In addition, although our study regions were 75–150 miles away from each other, and the hospitals were localized in villages or cities which differ notably with regards to population and structure, most S. enterica serovar Typhi isolates belonged to phage type D1. Therefore, the spread of a clonal bacterial population within Ghana cannot be discounted.

Although an extraordinarily high percentage of chloramphenicol resistance was obvious, this drug still was considered the first choice treatment for typhoid fever in 2001 in Ghana. Therefore, the high rate of S. enterica serovar Typhi was not unexpected. Similarly, 91.7% of all S. enterica were resistant to chloramphenicol in 2009 (Table 2). In both study periods, second-line antimicrobial agents, e.g., trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or ampicillin, also showed a high rate of resistance. This finding was in agreement with those of other studies from nonindustrialized countries (10). The rate of cefuroxime-resistant bacteria increased from 18.9% to 41.7% because of a higher percentage of cefuroxime-resistant enterobacteriaceae other than Salmonella (50.0% vs. 87.5%, Table 2).

In 2001–2002, most bacteria were susceptible to ciprofloxacin (Table 2), as had been shown for S. enterica from blood cultures of Nigerian patients (11). In contrast, for S. enterica serovar Typhi isolated in 1997–1999 in Kenya, MICs of ciprofloxacin were noticeably higher than for those strains isolated during 1988–1993 (12,13).

Although ciprofloxacin proved to be effective against S. enterica in our study, the resistance rate of enterobacteriaceae other than S. enterica against this quinolone increased from zero in 2001–2001 to 50.0% in 2009 (Table 2). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus was not identified as a cause of BBSI during either period.

When we assessed the situation in individual regions, notable differences were obvious. Comprising 47.5% of all BBSI, typhoid fever was most prevalent in Assin Foso in 2001–2002. In contrast, not even 1 case occurred in 2009. Analyzing the situation in that urban area, the following conditions were found: 1) sanitation was improved; 2) additional toilets were established; 3) ciprofloxacin was widely used in hospital for treating infections; and 4) ciprofloxacin was easily available at local street traders. Although the broad application of ciprofloxacin has to be critically discussed, the observed absence of typhoid fever in Assin Foso is impressive.

In contrast, S. enterica serovar Typhi was isolated from 27.8% of cases of BBSI in Eikwe in 2001–2002 and remained at a high rate of 30.2% in 2009. In this small fishing village, the situation differed noticeably from that in Assin Foso. Although additional toilets had been constructed, sanitation was not much improved; most residents still used the beach for defecation. In addition, ciprofloxacin was not extensively prescribed in the hospital and was not available at local street traders. Thus, educational programs to encourage use of public toilets plus adequate prescription of ciprofloxacin might help control typhoid here in the future.

Conclusions

Although Ghana implemented several measures to control typhoid, our study found that, depending on the region, S. enterica serovar Typhi remains the most prevalent bacterial species causing BBSI. This finding is in agreement with a recent study from the Ashanti region, where 12.4% of BBSI were caused by S. enterica serovar Typhi (14). In addition, emergent ciprofloxacin resistance has been described in Accra, the capital of Ghana (15). Therefore, the implementation of bacteriologic diagnosis should be considered even in smaller hospitals in a rural African setting to monitor pathogen distribution and resistance rates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients in Ghana for participating in this study and Nicholas Amgborme, Marcelina Gruszka, Paul Harriban, Kwame Buadu Mahdi, and Samuel Numafo for their help in collecting the bacterial isolates from blood cultures.

This study was partly supported by a grant from Bayer Social Health Care Programs.

This article is dedicated to our friend, Nicholas Amgborme from Eikwe, who passed away much too soon.

Biography

Dr Uwe Groß is head of the Institute of Medical Microbiology at the University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany, and since 2000 has helped establish bacteriology laboratories in missionary hospitals in rural settings in Ghana. His current research concentrates on campylobacteriosis, toxoplasmosis, and infectious diseases caused by pathogenic fungi.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Groß U, Amuzu SK, de Ciman R, Kassimova I, Groß L, Rabsch W. Bacteremia and antimicrobial drug resistance over time, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Oct [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/edi1710.110327

References

- 1.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:309–17. 10.1086/421946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enweronu-Laryea CC, Newman MJ. Changing pattern of bacterial isolates and antimicrobial susceptibility in neonatal infections in Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana. East Afr Med J. 2007;84:136–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkley JA, Lowe BS, Mwangi I, Williams T, Bauni E, Mwarumba S, et al. Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:39–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa040275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shears P. Antibiotic resistance in the tropics. Epidemiology and surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in the tropics. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:127–30. 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90134-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Approved standard M2-A7. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 7th ed. Wayne (PA): The Committee; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward LR, de Sa JDH, Rowe B. A phage-typing scheme for Salmonella enteritidis. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;99:291–4. 10.1017/S0950268800067765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghana Ministry of Health. Standard treatment guidelines—Ghana. Chapter 13: infectious diseases and infestations, typhoid fever. Accra (Ghana): Ghana National Drugs Programme; 2004. p. 211–2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheesbrough JS, Taxman BC, Green SD, Mewa FI, Numbi A. Clinical definition for invasive Salmonella infection in African children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:277–83. 10.1097/00006454-199703000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochiai RL, Wang XY, von Seidlein L, Yang J, Bhutta ZA, Bhattacharya SK, et al. Salmonella paratyphi A rates, Asia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1764–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1770–82. 10.1056/NEJMra020201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim YK, Adedare TA, Ehinmidu JO. Antibiotic sensitivity profiles of Salmonella organisms isolated from presumptive typhoid patients in Zaria, northern Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2005;34:109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kariuki S, Gilks C, Revathi G, Hart CA. Genotypic analysis of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:649–51. 10.3201/eid0606.000616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Threlfall EJ, Ward LR, Skinner JA, Smith HR, Lacey S. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella typhi and treatment failure. Lancet. 1999;353:1590–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01001-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks F, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Hünger F, Sarpong N, Ekuban S, Agyekum A, et al. Typhoid fever among children, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1796–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Namboodiri SS, Opintan JA, Lijek RS, Newman MJ, Okeke IN. Quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli from Accra, Ghana. [Epub ahead of print]. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:44. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]