Abstract

This study was designed to improve AAV-mediated gene transfer to the murine submandibular salivary glands. Our first aim was to utilize AAV pseudotype vectors, containing the genetic elements of the canonical AAV2, packaged within capsids of AAV serotypes 5, 8, and 9. Having determined that this pseudotyping increased the efficiency of gene transfer to the glands by several orders of magnitude, we next asked whether we could reduce the gene transfer inoculum of the pseudotype while still achieving gene transfer comparable with that achieved with high-dose AAV2. Having achieved gene transfer comparable with that of AAV2 using a pseudotype vector (AAV2/5) at a 100-fold lower dose, our final objective was to evaluate the implications of this lower dose on two pre-clinical parameters of vector safety. To evaluate systemic toxicity, we measured AAV vector sequestration in the liver using qPCR, and found that the 100-fold lower dose reduced the vector recovered from the liver by 300-fold. To evaluate salivary gland function, we undertook whole-proteome profiling of salivary gland lysates two weeks after vector administration and found that high-dose (5 × 109) AAV altered the expression level of ~32% of the entire salivary gland proteome, and that the lower dose (5 × 107) reduced this effect to ~7%.

Keywords: gene therapy, gene transfer techniques, adeno-associated virus, proteomics, toxicity, transgenes

Introduction

Gene transfer to the salivary gland has broad therapeutic potential for both oral and systemic diseases (Perez et al., 2010). Since the first report of successful expression of a foreign transgene in the salivary gland of a rodent in 1994 (Mastrangeli et al., 1994), retroductal cannulation and viral vector-mediated gene transfer have been described in numerous studies. Positive pre-clinical gene therapy results have been shown in models of salivary gland diseases such as Sjögren’s Syndrome and in acquired conditions such as xerostomia secondary to ionizing radiation of the head and neck. In the overall context of increasing evidence from human clinical trials that gene therapy is safe and effective, including a first-in-man trial involving salivary gland gene transfer (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00372320), therapeutic gene transfer to the human salivary gland appears to be close to becoming a practicable reality.

Ongoing human gene therapy clinical trials unrelated to the salivary gland, combined with rodent, swine, and non-human primate (NHP) studies involving salivary gland gene transfer, illuminate the technological challenges that face implementation of viral vector-mediated salivary gland gene transfer in humans. First, a side-by-side comparison of multiple viral vectors in the salivary gland indicates that Adenovirus (Ad) and Adeno-associated virus (AAV) are the most viable vector systems for clinical implementation at this time (Shai et al., 2002). Second, the current state of adenoviral technology falls short of a realistic solution for gene therapy interventions requiring long-term gene expression. This limitation is due to the related observations that Ad drives very short-lived (< 2 wks) gene expression in vivo, and is strongly immunogenic on repeated administration.

AAV does not appear to have the same limitations as Ad with respect to in vivo gene expression. In particular, AAV has been shown to express in the salivary glands of rodents for periods exceeding 1 yr (Voutetakis et al., 2004) and for periods > 32 wks in swine (Hai et al., 2009). Taken together with recent reports of safety and efficacy utilizing AAV in human clinical trials in diseases such as Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis (Maguire et al., 2009), and Factor IX hemophilia (Manno et al., 2006), AAV appears to be a promising candidate for salivary gland gene transfer in applications requiring long-term gene expression. In light of the great potential for salivary gland gene therapy applications in chronic diseases such as Sjögren’s Syndrome, the potential to deliver gene therapeutics in saliva, and possibly even treat systemic disorders with salivary gland gene transfer (Voutetakis et al., 2005), there is an imminent need to optimize this promising gene delivery system for clinical applications in the salivary gland.

The present study was undertaken in the context of earlier reports showing that alternate AAV serotypes (e.g. AAV5) accomplish gene transfer in the salivary glands of rodents (Katano et al., 2006) and NHP (Voutetakis et al., 2007, 2010) more efficiently than the canonical AAV2 vector. Our central hypothesis was that, by utilizing an alternate AAV pseudotype vector, we could achieve gene expression levels comparable with the canonical AAV2 vector by using lower doses of the pseudotype vector. Notably, our approach compared gene transfer with AAV2 to alternate AAV vector pseudotypes (e.g. AAV2/5), rather than alternate serotypes [e.g. AAV5/5 (Katano et al., 2006)] as in similar prior reports, allowing us to parse out gene transfer efficiency gains accruing to alternate capsids while retaining the AAV2 genetic elements. After our results demonstrated the validity of this hypothesis, we then explored whether reducing the gene transfer inoculum would improve two pre-clinical metrics of vector safety: (1) systemic toxicity, as represented by AAV vector detection in the liver; and (2) whole-proteome profiling of the transduced salivary gland as a measure of alterations in salivary gland physiology as a result of vector-mediated gene transfer.

Materials & Methods

Viral Vectors

AAV2 vectors packaged with the various serotype capsids and expressing the Luc2 reporter gene under the control of a CMV promoter were obtained from the NHLBI Gene Therapy Research Program Preclinical Vector Core at the University of Pennsylvania.

Animals and Gene Transfer

Mice of the strain C57BL/6 were obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained in pathogen-free conditions in a rodent vivarium, with access to standard chow and water ad libitum. Animal experiments and protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Allegheny-Singer Research Institute. Gene transfer to the salivary gland was accomplished as we have previously described (Passineau et al., 2011); see the Appendix for details. The reader should note that the animals used in this study were of a different strain than the Balb/c strain utilized in earlier studies (Katano et al., 2006).

In vivo Luciferase Imaging

Mice were anesthetized and injected intraperitoneally with the D-Luciferin substrate (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA) at a dose of 150 mg/10 g body weight. The mice were then placed in the IVIS Lumina II chamber containing a cryogenically cooled CCD camera to quantify photons spontaneously emitted by the animal. Images were pseudocolored with the use of Xenogen software and overlaid on a black-and-white photograph of the animal generated with cabinet lighting. The visual output represents the number of photons emitted/sec/cm2 as a pseudocolor image, where the maximum is red and the minimum is purple.

qPCR for Viral Genomes in Tissue

Seven days after AAV treatment, mice were sacrificed and their livers flash-frozen. Genomic and viral DNA were co-purified from livers with the QIAamp mini purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following standard protocols and including an RNase treatment. Total DNA quantitation was determined, and 50 ng of samples were used as a template in qPCR. qPCR was performed with the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as previously described (Zincarelli et al., 2008), except that we used a luc2 plasmid standard and the following luc2 primers: luc2-F (5′-CTACTTGA TCTGCG GCTTTCG-3′) and luc2-R (5′-AGCAGGGCAGATT GAATCTTATAGTCT-3′). Standards and samples were run in triplicate on an ABI7900HT, and viral genome copies/μg were calculated as previously described (Zincarelli et al., 2008).

2-D-difference Gel Electrophoresis (DiGE)

Fourteen days after AAV treatment, animals were sacrificed and salivary glands harvested and homogenized in ice-cold T-PER (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Comparative samples were labeled with different Cy dyes and run on the same 2-D gel, with an internal standard labeled with a third Cy dye. Multiple gels were run, with dye switching, to achieve statistical comparisons. Gels were scanned with a Typhoon Trio, and images were processed with the DeCyder software package (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Details of the DiGE procedure and statistical analysis are outlined in the Appendix.

Results

AAV Pseudotyping Dramatically Alters the Efficiency of Gene Transfer to the Submandibular Salivary Gland

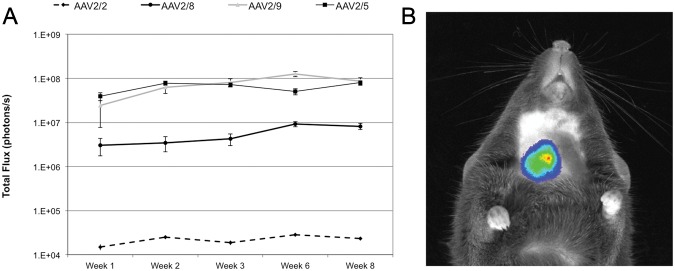

In our first experiment, we compared relative gene transfer efficiency with AAV2/2 vs. pseudotypes 2/5, 2/8, and 2/9 using a dose of 5 × 109vg unilaterally to the submandibular gland. Fig. 1 shows relative gene transfer for the 4 vectors, demonstrating dramatically enhanced gene transfer with AAV2/5 and AAV2/9. Gene expression was generally stable for 8 wks following gene delivery. Gene expression was anatomically well-localized to the region of the submandibular gland (Fig. 1B). Immediately prior to their death in week 16, animals were imaged, and we observed that Luc signal had fallen to near or below the threshold of detection.

Figure 1.

Relative reporter gene activity over time following treatment with 5E9 vector genomes of pseudotyped AAV vectors to the right submandibular duct. (A) All pseudotypes showed substantially enhanced gene expression at this dose relative to the canonical AAV2/2. Gene expression is reported as total flux (photons/sec) recorded by the CCD camera. (B) Anatomical localization of the photon signal, pseudocolored for intensity and superimposed on a photograph of the animal. N = 8 for AAV2/2, n = 6 for AAV2/8 and 2/9, and n = 5 for AAV2/5. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis in an autoregressive model with heterogeneous variance and a post hoc Tukey test revealed highly significant (p < 0.01) differences between AAV2/2 and all pseudotypes studied. AAV2/5 and AAV2/9 were highly significantly different (p < 0.01) from AAV2/8 at all time-points, and significantly different (p < 0.05) from one another at week 6.

AAV5 Pseudotype Facilitates Reduction of Gene Transfer Inocula

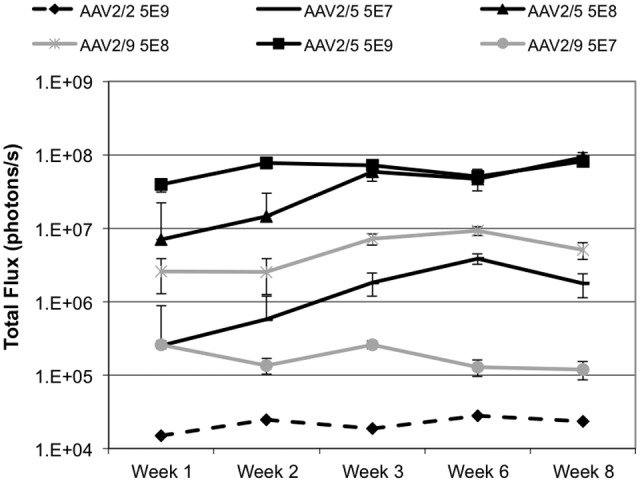

We next sought to determine the relationship between doses of AAV2/2 and AAV2/5 needed to achieve equivalent gene transfer. Using 5 × 109 viral genomes of AAV2/2 in mouse submandibular glands as a common dosage referred to in earlier literature, we tested AAV2/5-mediated gene transfer at doses of 5 × 108 and 5 × 107. Results of these experiments are presented in Fig. 2. We found intensity of gene expression with AAV2/5 at the 5 × 107 dose to be ~100× higher than that with AAV2/2 at the 5 × 109 dose, leading us to estimate that AAV2/5 is roughly 1,000-10,000× more efficient in accomplishing gene expression in the mouse submandibular gland than is the canonical AAV2/2.

Figure 2.

Relative reporter gene activity with different doses of pseudotyped vectors delivered to the right submandibular gland. AAV2/5 at the lowest dose (5E7) was higher than AAV2/2 at the high dose (5 x 109, dashed line). AAV2/5 was somewhat more efficient than AAV2/9 (grey lines), and reached its maximum at a total flux of 1 x 108, which is effectively the upper bound of meaningful quantitation of this system in our hands. Gene expression is reported as total flux (photons/sec) recorded by the CCD camera. N = 6 per dose group of AAV2/5. For AAV2/9, n = 8 for 5 x 107 and n = 6 for 5 x 108. N = 7 for AAV2/2. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis in an autoregressive model with heterogeneous variance and a post hoc Tukey test revealed highly significant (p < 0.01) differences between AAV2/2 5 x 109 and AAV2/5 5 x 109 and 5 x 108. Differences between AAV2/2 5 x 109 and AAV2/5 5 x 107 did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.083). AAV2/9 gene expression data are presented in grey for comparison purposes only and were not evaluated statistically.

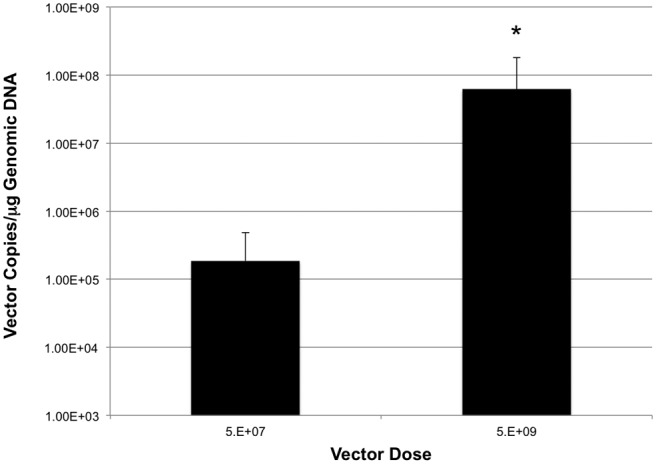

Reduction of Gene Transfer Inoculum Dramatically Reduces Vector Leakage from the Salivary Gland

Escape of the vector across the salivary gland epithelial barrier exposes the vector to the systemic circulation, resulting in potential for toxicity and host immune response. By reducing the gene transfer inoculum, we reasoned that this undesirable exposure of the vector to the systemic circulation could be minimized. One week after salivary gland delivery of AAV2/5 at doses of 5 × 109 and 5 × 107vector genomes, livers were harvested from treated animals and qPCR performed to quantitate viral genomes. As expected, reducing the gene transfer inoculum 100-fold reduced vector leakage from the salivary gland to the liver by ~300-fold (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

AAV genomes recovered from livers 7 days following treatment as a function of dosage delivered to the submandibular gland. Lowering the vector dosage 100-fold reduced the number of vector genomes recovered from the liver by ~300-fold. N = 5/dose. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between the groups (p < 0.05) as determined by a one-way ANOVA and a post hoc two-tailed t test. Error bars are ± SD.

AAV-mediated Transgene Expression Results In Major Changes to the Salivary Gland Proteome, and Reduction of Gene Transfer Inoculum Reduces These Alterations Relative to Untreated Glands

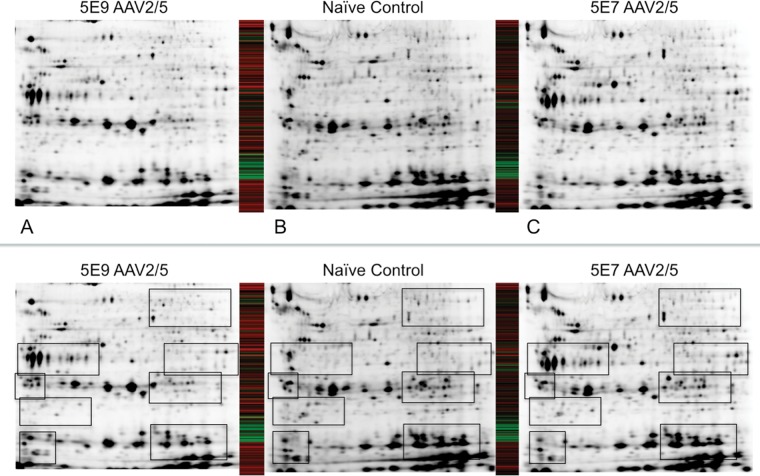

AAV is a very promising vector for salivary gland gene therapy, due to its ability to establish stable, long-term gene expression and its relatively mild immunoprovocative profile (Kok et al., 2005). We sought to understand the effect of stable AAV-mediated gene expression by performing 2-dimensional-difference gel electrophoresis on salivary gland homogenates to characterize changes in whole-proteome expression profiles in response to viral-mediated gene transfer. We allowed 2 wks to elapse between AAV delivery and our proteomic studies, to allow for establishment of reporter gene expression. We were able to reliably and reproducibly image ~3200 spots on our 2-D gels, and gene transfer with our 5 × 109 dose altered the expression patterns of ~32% of these proteins with a threshold setting of 1.5-2.5 (Figs. 4A, 4B). Next, we explored whether a lower dose of vector (5 × 107) would lessen this effect. To our surprise, the lower dose of vector had a dramatically lesser effect upon the salivary gland proteome, with only ~7-10% of the proteins meeting the 1.5-2.5 threshold (Figs. 4B, 4C). A comparison of AAV2/2 and AAV2/5 at the 5 × 109 dose is provided in the Appendix.

Figure 4.

Whole-proteome profiling of salivary gland lysates 14 days following treatment, and comparison of proteomic profiles of submandibular glands treated with 5 × 109 or 5 × 107 vector genomes of AAV2/5. Panel B is a lysate from a naïve salivary gland, which served as the control for comparison with the 5 × 109 dose (Panel A) and the 5 × 107 dose (Panel C). The heat maps show comparison of expression levels of 3211 proteins between the two panels to which they are adjacent. Taking Panel B as baseline, the heat maps represent a protein that is significantly (p < 0.05) up-regulated as green and down-regulated as red. Black represents no significant change from baseline. Annotated versions of panels A-C highlight regions of most significant change.

Discussion

The findings of this study support the hypothesis that gene transfer to the salivary gland with the AAV2/5 pseudotyped vector allows us to reduce the gene transfer inoculum relative to the canonical AAV2/2 vector system, and that this reduction in dosing significantly mitigates both systemic toxicity and vector-induced alterations in the normal physiology of the salivary gland. By utilizing a semi-quantitative reporter gene system, we have directly indexed the magnitude of gene transfer with AAV2/5 to AAV2/2. Based upon a substantial body of literature showing functional levels of gene expression with 1 × 109−1 × 1010 vector genomes/gland of AAV2/2, we can report similar levels of gene transfer, which would be assumed to reach a therapeutically relevant threshold, with as little as 1 × 107 vg of AAV2/5. By reducing the dosage of the vector 100-fold, we saw a profoundly reduced impact upon the normal functioning of the salivary gland, as evidenced by whole-proteome profiling. The therapeutic implications of these findings, particularly in the paradigm of chronic treatment and retreatment with AAV vectors, will need to be explored in future studies.

Our findings follow two earlier studies utilizing the AAV5 serotype (in contrast to our pseudotype) vector to accomplish gene transfer to the salivary glands, first in rodents (Katano et al., 2006) and subsequently in non-human primates (Voutetakis et al., 2010). These prior studies showed enhanced transduction of the salivary gland with AAV5/5 vs. AAV2/2, as well as host immune reaction against the AAV5/5 vector. Our results should be considered against the backdrop of these prior studies, since by utilizing alternate pseudotypes rather than serotypes, we are able to parse out transductional effects of the AAV5 capsid in isolation from AAV5-specific genetic elements (i.e., inverted terminal repeats). Indeed, our results seem to show much greater gene transfer efficiency of AAV5/2 as opposed to that previously reported in mice with AAV5/5 [see Fig. 1 from Katano et al. (2006) relative to Fig. 1 from this report]. It is tempting to speculate that this phenomenon is related to impaired concatamer formation with AAV5/5, as was shown in non-human primates (Voutetakis et al., 2010). Concatamer formation following AAV5/5 gene transfer has never been evaluated in mice, but it may explain this discrepancy between AAV5/5 and AAV2/5, and this may hint at a species-independent phenomenon.

Our observation that this 100-fold reduction in vector dose results in > 100-fold less vector leakage to the systemic circulation is not surprising, but the translational implications of this finding are potentially significant. AAV-associated liver toxicity is generally not a major concern in human gene therapy, particularly at the doses salivary gland gene therapy would require, but exposure of the vector to the systemic circulation raises concerns of host immune response. Very few clinical trial data are available regarding human host immune response to an AAV therapeutic vector as a function of dose, but one recent clinical trial reported anti-AAV capsid CTL response as follows: 1 out of 2 in the highest dose cohort, 1 out of 3 in the middle dose cohort, and 0 out of 2 in the lowest dose cohort (Manno et al., 2006). These data are far from conclusive with regard to this question, but do offer preliminary support for the intuitive hypothesis that decreasing doses of AAV should reduce host immune response (Mingozzi and High, 2011). Since the salivary gland is considered an immunoprivileged organ (Novak et al., 2008), and the mucosal barrier is breached following AAV2 gene transfer in the rodent salivary gland (Wang et al., 2006), it is possible that some of the anti-AAV immune response previously reported (Kok et al., 2005; Katano et al., 2006) may be mitigated by our strategy of reducing the gene transfer inoculum and thereby reducing systemic exposure of the host to the vector. It is important to exercise caution when extrapolating to humans any findings related to host immune response in mouse studies, but it is logical to assume that reducing exposure of the vector to the systemic circulation using our strategy is a meaningful translational consideration.

Taken together, and in the context of prior literature and clinical trial reports, these results lead us to suggest that AAV2/5 is the most promising vector system yet identified for salivary gland gene transfer. With the first human clinical trial involving gene transfer to the salivary gland currently under way, immediate consideration of this technology in the design of future clinical trials is warranted, but two remaining issues must be addressed. First, studies in NHPs should address the hypothesis that the AAV2/5 pseudotype, which embodies the AAV2 genetic elements shown to facilitate concatamer formation in NHP salivary glands (Voutetakis et al., 2010), will overcome the limitations of the AAV5/5 vector that resulted in previously disappointing gene transfer results in the salivary glands of NHPs. Second, host immune response to the vector at decreasing doses should be rigorously evaluated, testing our hypothesis that lower vector inoculum with AAV2/5 will bring the doses below an immunoprovocative threshold and allow for periodic re-dosing throughout the lifetime of the treated individual.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Julie Johnston for her helpful advice regarding the study design and Dr. Kelly Shields for assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant 5R00DE018188 (to MJP). The authors acknowledge the Gene Therapy Resource Program of the NHLBI, NIH, for providing the gene transfer vectors used in this study.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

The authors certify that this work is free from conflict of interest.

References

- Hai B, Yan X, Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Cotrim AP, Shan Z, et al. (2009). Long-term transduction of miniature pig parotid glands using serotype 2 adeno-associated viral vectors. J Gene Med 11:506-514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katano H, Kok MR, Cotrim AP, Yamano S, Schmidt M, Afione S, et al. (2006). Enhanced transduction of mouse salivary glands with AAV5-based vectors. Gene Ther 13:594-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MR, Voutetakis A, Yamano S, Wang J, Cotrim A, Katano H, et al. (2005). Immune responses following salivary gland administration of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vectors. J Gene Med 7:432-441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire AM, High KA, Auricchio A, Wright JF, Pierce EA, Testa F, et al. (2009). Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber’s congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 374:1597-1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, et al. (2006). Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med 12:342-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangeli A, O’Connell B, Aladib W, Fox PC, Baum BJ, Crystal RG. (1994). Direct in vivo adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to salivary glands. Am J Physiol 266(6 Pt 1):G1146-G1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingozzi F, High KA. (2011). Immune responses to AAV in clinical trials. Curr Gene Ther 11:321-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak N, Haberstok J, Bieber T, Allam JP. (2008). The immune privilege of the oral mucosa. Trends Mol Med 14:191-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passineau MJ, Fahrenholz T, Machen L, Zourelias L, Nega K, Paul R, et al. (2011). alpha-Galactosidase A expressed in the salivary glands partially corrects organ biochemical deficits in the Fabry mouse through endocrine trafficking. Hum Gene Ther 22:293-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez P, Rowzee AM, Zheng C, Adriaansen J, Baum BJ. (2010). Salivary epithelial cells: an unassuming target site for gene therapeutics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:773-777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shai E, Falk H, Honigman A, Panet A, Palmon A. (2002). Gene transfer mediated by different viral vectors following direct cannulation of mouse submandibular salivary glands. Eur J Oral Sci 110:254-260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutetakis A, Kok MR, Zheng C, Bossis I, Wang J, Cotrim AP, et al. (2004). Reengineered salivary glands are stable endogenous bioreactors for systemic gene therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:3053-3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutetakis A, Bossis I, Kok MR, Zhang W, Wang J, Cotrim AP, et al. (2005). Salivary glands as a potential gene transfer target for gene therapeutics of some monogenetic endocrine disorders. J Endocrinol 185:363-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Mineshiba F, Cotrim AP, Goldsmith CM, Schmidt M, et al. (2007). Adeno-associated virus serotype 2-mediated gene transfer to the parotid glands of nonhuman primates. Hum Gene Ther 18:142-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Cotrim AP, Mineshiba F, Afione S, Roescher N, et al. (2010). AAV5-mediated gene transfer to the parotid glands of non-human primates. Gene Ther 17:50-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Voutetakis A, Mineshiba F, Illei GG, Dang H, Yeh CK, et al. (2006). Effect of serotype 5 adenoviral and serotype 2 adeno- associated viral vector-mediated gene transfer to salivary glands on the composition of saliva. Hum Gene Ther 17:455-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Rengo G, Rabinowitz JE. (2008). Analysis of AAV serotypes 1-9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol Ther 16:1073-1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]