SUMMARY

There are two major forms of long-term depression (LTD) of synaptic transmission in the central nervous system that require activation of either N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). In synapses in the perirhinal cortex, we have directly compared the Ca2+ signaling mechanisms involved in NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD. While both forms of LTD involve Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, the Ca2+ sensors involved are different; NMDAR-LTD involves calmodulin, while mGluR-LTD involves the neuronal Ca2+ sensor (NCS) protein NCS-1. In addition, there is a specific requirement for IP3 and PKC, as well as protein interacting with C kinase (PICK-1) in mGluR-LTD. NCS-1 binds directly to PICK1 via its BAR domain in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Furthermore, the NCS-1-PICK1 association is stimulated by activation of mGluRs, but not NMDARs, and introduction of a PICK1 BAR domain fusion protein specifically blocks mGluR-LTD. Thus, NCS-1 plays a distinct role in mGluR-LTD.

INTRODUCTION

Long-lasting modifications in the function of synapses in the brain, termed synaptic plasticity, underlie learning and memory (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). Induction of long-term synaptic plasticity requires activation of postsynaptic glutamate receptors (Collingridge et al., 1983), and this activation leads to a rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ levels (Lynch et al., 1983; Malenka et al., 1992; Artola and Singer, 1993). Two major forms of LTD have been identified, which are distinguished on the basis of whether they are triggered via the activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) (Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Dudek and Bear, 1992) or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (Bashir et al., 1993; Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994). Both forms of LTD can coexist at the same set of synapses and utilize different signaling and expression mechanisms (Oliet et al., 1997). This raises the important issue of how the Ca2+ signals associated with the induction of NMDAR-dependent LTD (NMDAR-LTD) and mGluR-dependent LTD (mGluR-LTD) are distinguished. In the case of NMDAR-LTD, several Ca2+-sensitive enzymes have been implicated in the process, including calmodulin, which activates calcineurin (Mulkey et al., 1993; Morishita et al., 2005), and hippocalcin (Palmer et al., 2005), a member of the neuronal Ca2+ sensor (NCS) family (Burgoyne, 2007). In addition, protein interacting with C kinase (PICK1) is Ca2+ sensitive, mediates NMDAR-dependent endocytosis of AMPARs (Hanley and Henley, 2005), and is involved in both hippocampal LTP and LTD (Terashima et al., 2008). In contrast, much less is known about the Ca2+ sensors involved in mGluR-LTD, although PICK1 has been implicated in mGluR-LTD in the cerebellum and ventral tegmental area (Xia et al., 2000; Bellone and Lüscher, 2006).

The perirhinal cortex is a transitional cortex interposed between the neocortex and the hippocampal formation and is essential for paired associative learning and recognition memory (Mandler, 1980; Brown and Aggleton, 2000). Loss of recognition memory is a major symptom of the amnesic syndrome and early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (Blaizot et al., 2002; Barbeau et al., 2004). It has been shown that recognition memory involves the decrement of responses to repeated stimuli and that this long-term change in neuronal responsiveness shares many properties with LTD. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of LTD in the perirhinal cortex is of fundamental importance for understanding this form of learning. Both NMDARs and mGluRs are involved in perirhinal-based, visual object recognition memory (Barker et al., 2006a; Barker et al., 2006b). By understanding the molecular differences between these two forms of LTD in this brain region, it should be possible to establish their relative functions in learning and memory in this brain structure.

In the present study, we have directly compared NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD at synapses in the perirhinal cortex. Our results demonstrate the existence of two distinct signaling pathways that possess differing Ca2+ sensitivities. Whereas NMDAR-LTD requires the calcium sensor calmodulin, mGluR-LTD depends specifically on NCS-1, the prototypic member of the NCS family. We find that NCS-1 binds directly to the BAR domain of PICK1 in a Ca2+-dependent manner and that the association between these two proteins is enhanced following stimulation of mGluRs. RNAi knockdown of NCS-1 or interfering with PICK1 BAR domain interactions blocks specifically mGluR-LTD. Our results, therefore, provide additional insights into mechanisms involved in the induction of one of the major forms of LTD in the brain.

RESULTS

NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD Are Independent Forms of Plasticity that Coexist at Perirhinal Synapses

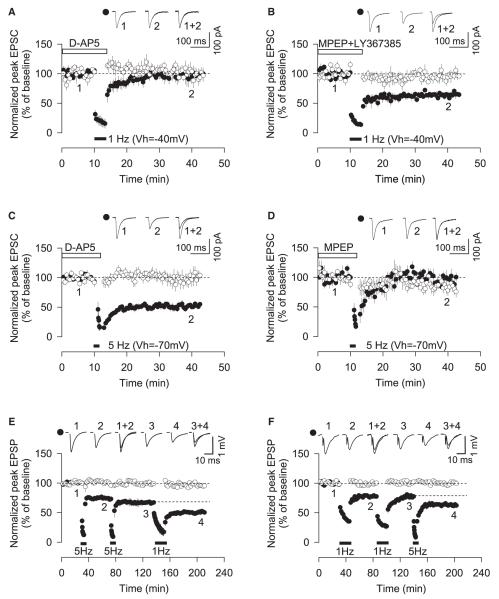

We performed experiments at synapses of perirhinal cortex where both NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD can be readily induced in the same neurons by altering the frequency of afferent stimulation without the need for manipulating the bathing solutions. We have shown previously that 1 Hz stimulation induces NMDAR-LTD, whereas 5 Hz stimulation induces mGluR-LTD (Jo et al., 2006; Park et al., 2006). In the present study, we used slices obtained from 7- to 13-day-old rats. We confirmed that, at this age, 1 Hz stimulation selectively induced NMDAR-LTD since it was blocked by D-AP5 (99% ± 8% of baseline, n = 6) (Figure 1A) and was unaffected by the coapplication of an mGlu1 antagonist, LY367385, and an mGlu5 antagonist, MPEP (65% ± 7%, n = 5) (Figure 1B). In contrast, 5 Hz stimulation selectively induced NMDAR-independent LTD (56% ± 4%, n = 6) (Figure 1C) that was blocked by MPEP (96% ± 8%, n = 5) (Figure 1D), showing that it was induced via the activation of mGlu5 receptors.

Figure 1. mGluR-LTD and NMDAR-LTD Coexist in the Perirhinal Cortex.

(A) Pooled data (n = 6) of EPSC amplitude versus time to show that D-AP5 (50 μM) blocks 1 Hz LTD (200 shocks, −40 mV).

(B) MPEP (1 μM) and LY367385 (50 μM) have no effect on 1 Hz LTD (n = 5).

(C) D-AP5 has no effect on 5 Hz (200 shocks, −70 mV) induced LTD (n = 6).

(D) MPEP blocks 5 Hz LTD (n = 5).

(E) Pooled data (n = 5) of fEPSP amplitude versus time to show that 1 Hz stimulation (900 shocks) in the presence of MPEP and LY367385 induces LTD following saturation of LTD induced by 5 Hz stimulation (900 shocks in the presence of D-AP5).

(F) Pooled data (n = 4) of fEPSP amplitude versus time to show that 5 Hz stimulation (900 shocks) in the presence of D-AP5 induces LTD following saturation of LTD induced by 1 Hz stimulation (900 shocks).

Error bars, SEM. Filled symbols show the input in which 1 Hz and/or 5 Hz stimulation was delivered, and open symbols show the control input.

We next examined whether the induction of NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD converged at the level of expression or were two fully independent processes by performing cross-saturation experiments using field potential recording. Stimulation at 5 Hz (900 shocks) induced LTD in the presence of D-AP5 that, although somewhat smaller in magnitude than that induced using whole-cell recording, was saturated after a single episode of stimulation. Under these conditions, LTD could still be readily induced by 1 Hz stimulation (900 shocks) delivered in the presence of both mGlu1 and mGlu5 antagonists (first 5 Hz stimulation, 78% ± 2%; second 5 Hz stimulation, 74% ± 4% of initial baseline [p > 0.05]; 1 Hz stimulation, 52% ± 2% of initial baseline, n = 5 [p < 0.01]) (Figure 1E). Similarly, 1 Hz stimulation induced LTD that was also somewhat smaller than obtained with whole-cell recording but again saturated after a single episode of stimulation, since a second episode of 1 Hz stimulation failed to induce additional LTD. However, 5 Hz stimulation in the presence of D-AP5 induced further LTD (first 1 Hz stimulation, 75% ± 3%; second 1 Hz stimulation, 74% ± 3% [p > 0.05]; 5 Hz stimulation, 60% ± 2%, n = 4 [p < 0.01]) (Figure 1F). These experiments show that NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD are fully independent forms of synaptic plasticity at the levels of both induction and expression.

Differing Ca2+ Sensitivities of NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD

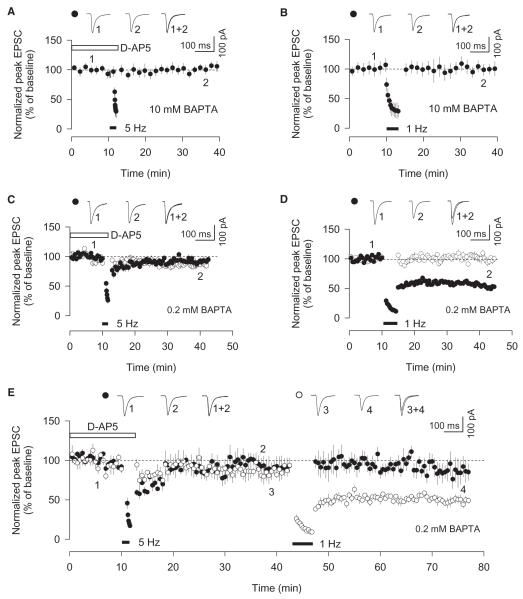

Chelating Ca2+ in the postsynaptic neuron prevents the induction of NMDAR-LTD (Mulkey and Malenka, 1992) and mGluR-LTD (Cho et al., 2000). In the present study, we compared the effects of chelating Ca2+, using different concentrations of BAPTA, on the two forms of LTD. In agreement with our previous work (Cho et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2001), we found that BAPTA (10 mM) prevented the induction of NMDAR-LTD (99% ± 6%, n = 4) (Figure 2A). This concentration of BAPTA also blocked the induction of mGluR-LTD (94% ± 9%, n = 4) (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, however, a lower concentration of BAPTA (0.2 mM) had a differential effect on the two forms of LTD, blocking mGluR-LTD (95% ± 5%, n = 10) (Figure 2C), but not affecting NMDAR-LTD (55% ± 3%, n = 10) (Figure 2D). This differential sensitivity to BAPTA was also observed if 5 Hz and 1 Hz stimulation was delivered in turn to the same neurons (5 Hz, 95% ± 10%; 1 Hz, 51% ± 7%, n = 5 [p < 0.001]) (Figure 2E). These results show differences in the postsynaptic Ca2+ requirements of mGluR-LTD and NMDAR-LTD. This might be due to different signaling mechanisms, in particular the Ca2+ sensors that transduce the Ca2+ rise into an alteration in synaptic efficiency.

Figure 2. NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD Have a Differential Sensitivity to BAPTA.

(A) Postsynaptic inclusion of BAPTA (10 mM) blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 4).

(B) Postsynaptic inclusion of BAPTA (10 mM) blocks NMDAR-LTD (n = 4).

(C) Postsynaptic inclusion of BAPTA (0.2 mM) blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 10).

(D) Postsynaptic inclusion of BAPTA (0.2 mM) does not block NMDAR-LTD (n = 10).

(E) Postsynaptic inclusion of BAPTA (0.2 mM) blocks mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, tested using the control input for the 5 Hz train in the same neurons (n = 5).

Error bars, SEM. Filled symbols show the input in which 1 Hz and/or 5 Hz stimulation was delivered, and open symbols show the control input (except for the 1 Hz train in [E]).

NMDAR-LTD, but Not mGluR-LTD, Requires Activation of Calmodulin

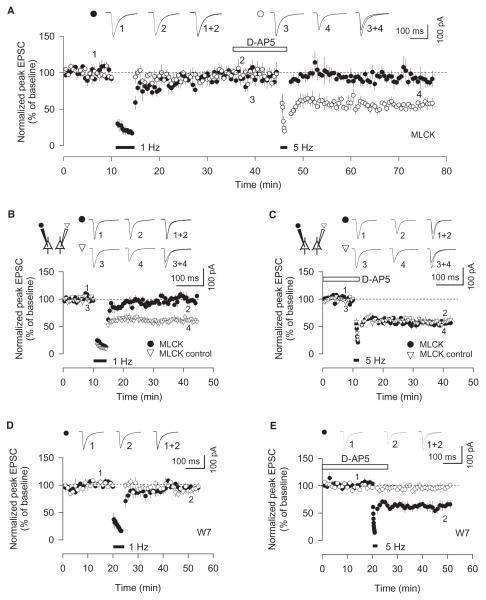

The induction of NMDAR-LTD requires the activation of Ca2+-/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatases, calcineurin, in the CA1 of the hippocampus (Mulkey et al., 1993, 1994; Morishita et al., 2005). To determine whether calmodulin has a role in NMDAR-LTD and/or mGluR-LTD in the perirhinal cortex, we used two approaches. Postsynaptic infusion of a calmodulin inhibitor peptide (R-R-K-W-Q-K-T-G-H-A-V-R-A-I-G-R-L-NH2) based on the calmodulin-binding domain of myosin light-chain kinase (10 μM MLCK; see Torok et al., 1998), blocked NMDAR-LTD but had no effect on mGluR-LTD in the same neurons (1 Hz, 96% ± 8%; 5 Hz, 58% ± 7%, n = 4) (Figure 3A). A similar finding was made when either 1 Hz stimulation or 5 Hz stimulation was delivered alone. In these experiments, two neurons in the same slice were recorded from simultaneously, one with an electrode containing MLCK and the other containing a control peptide (10 μM MLCK control; Trp and Leu replaced to Glu; R-R-K-E-Q-K-T-G-H-A-V-R-A-I-G-R-E-NH2). Thus, MLCK, but not MLCK-control peptide, blocked the induction of LTD induced by 1 Hz stimulation (MLCK, 98% ± 4%; MLCK-control peptide, 58% ± 4%, n = 6) (Figure 3B), while neither peptide affected the induction of LTD induced by 5 Hz stimulation (MLCK, 58% ± 6%; MLCK-control peptide, 59% ± 6%, n = 6) (Figure 3C). We also tested the effects of a different calmodulin inhibitor, W7, on the two forms of LTD (Figures 3D and 3E). Inclusion of W7 (1 mM; see Morishita et al., 2005) also blocked NMDAR-LTD (94% ± 8%, n = 5) (Figure 3D) but had no effect on mGluR-LTD (5 Hz, 66% ± 8%, n = 5 [p < 0.01]) (Figure 3E). These data confirm that calmodulin is important for NMDAR-LTD, but not required for the induction of mGluR-LTD.

Figure 3. Calmodulin Is Involved in NMDAR-LTD, but Not mGluR-LTD.

(A) Postsynaptic infusion of calmodulin inhibitor peptide MLCK (10 μM) blocks NMDAR-LTD, but not mGluR-LTD, tested using the control input for the 1 Hz train in the same neurons (n = 4).

(B) Using simultaneous dual-patch recording, infusion of MLCK peptide (10 μM) into one neuron blocks, while infusion of MLCK-control peptide (10 μM) into another neuron has no effect, on NMDAR-LTD (n = 6).

(C) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing no effect of either MLCK or MLCK-control peptide on mGluR-LTD (n = 6).

(D) Postsynaptic inclusion of W7 (1 mM) blocks NMDAR-LTD (n = 5).

(E) Postsynaptic inclusion of W7 (1 mM) has no effect on mGluR-LTD (n = 5).

Error bars, SEM. (A, D, and E) Filled symbols show the input in which 1 Hz and/or 5 Hz stimulation was delivered, and open symbols show the control input (except for the 5 Hz train in [A]).

A Role for Ca2+ Release from Intracellular Stores in Both NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD

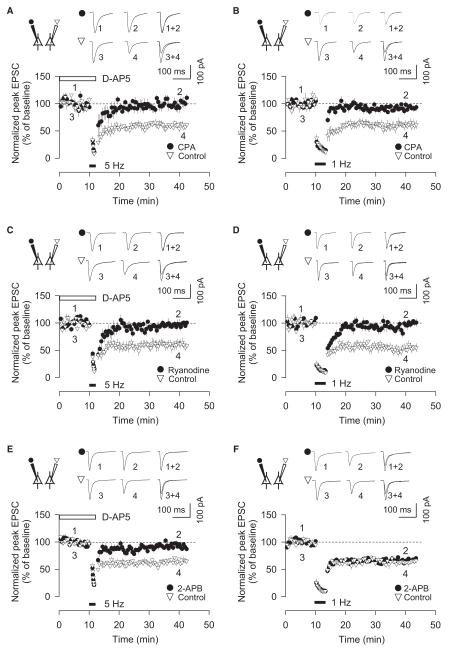

The requirement for a high concentration of BAPTA to block NMDAR-LTD is consistent with the idea that calmodulin is localized with NMDARs (Ehlers et al., 1996), where it is well placed to detect the Ca2+-permeating activated receptors. The greater sensitivity of mGluR-LTD to BAPTA plus its independence of calmodulin implies that a different Ca2+-signaling pathway is involved in this form of synaptic plasticity. Since mGlu5 receptors couple to phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC), a prime candidate is the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Consistent with this mechanism, treatment with cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; 10 μM), which depletes intracellular stores of their Ca2+, prevented LTD induced by 5 Hz stimulation (Figure 4A). Two neurons in the same slice were recorded from simultaneously, one with an electrode containing CPA and the other containing the control pipette solution. CPA consistently blocked the induction of LTD induced by 5 Hz stimulation (CPA, 102% ± 8%; control, 63% ± 4%, n = 5) (Figure 4A). Surprisingly, however, CPA also blocked LTD induced by 1 Hz stimulation (CPA, 96% ± 4% of baseline; control, 65% ± 7% of baseline, n = 5) (Figure 4B). To exclude a possible off-target effect of CPA, we also tested ryanodine, which depletes Ca2+ from intracellular stores by inducing a low-conductance state of the receptor. Ryanodine similarly blocked both forms of LTD (5 Hz ryanodine, 99% ± 4%; 5 Hz control, 64% ± 8%, n = 6) (Figure 4C) (1 Hz ryanodine, 99% ± 5%; 1 Hz control, 61% ± 7%, n = 6) (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. The Role of Ca2+ Release from Intracellular Stores in mGluR-LTD and NMDAR-LTD.

(A) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that CPA (10 μM) blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 5).

(B) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that CPA (10 μM) blocks NMDAR-LTD (n = 5).

(C) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that ryanodine (10 μM) blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 6).

(D) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that ryanodine (10 μM) blocks NMDAR-LTD (n = 6).

(E) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that 2-APB (10 μM) blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 5).

(F) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that 2-APB (10 μM) fails to block NMDAR-LTD (n = 5).

Error bars, SEM. Filled and open symbols show data from the neurons in which the patch pipette contained an inhibitor, and open symbols show the data from simultaneously recorded control neurons.

The release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores can be triggered by Ca2+ and/or by IP3. To determine whether IP3 is involved in either form of LTD, we used 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) in dual-patch experiments. We found that 2-APB selectively blocked mGluR-LTD (5 Hz 2-APB, 96% ± 3%; 5 Hz control, 68% ± 5% of baseline, n = 5) (Figure 4E) (1 Hz 2-APB, 66% ± 3%; control, 65% ± 3%, n = 5) (Figure 4F). Therefore, both NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD, in the perirhinal cortex, require the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores for their induction, but mGluR-LTD has a specific requirement for IP3.

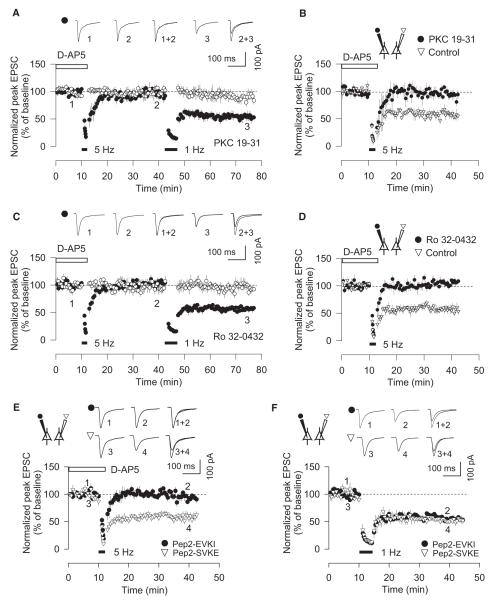

A Selective Involvement of PKC in mGluR-LTD

The sensitivity of both NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD to CPA and ryanodine suggests that Ca2+ is released from intracellular stores in response to the synaptic activation of both NMDARs and mGluRs. Therefore, the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores cannot be a specific induction signal for mGluR-LTD. This raises the question as to whether there are signaling mechanisms that are specific for mGluR-LTD. Since PLC-coupled receptors also can activate PKC, we next compared the role of PKC in both forms of LTD. Consistent with our previous study (Jo et al., 2006), the PKC inhibitory peptide PKC19-31 (10 μM) blocked the induction of mGluR-LTD. Here, we show that, in the same neurons, NMDAR-LTD was readily induced (5 Hz, 97% ± 4%; 1 Hz, 58% ± 8%, n = 5) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, using simultaneous dual-patch-clamp recording from neurons within the same slice, mGluR-LTD was blocked in cells loaded with the PKC19-31 (10 μM) but was readily induced in cells loaded with normal filling solution (PKC19-31, 95% ± 8%; control, 60% ± 6%, n = 4) (Figure 5B). Similar results were obtained using a different PKC inhibitor, {(S)-3-[8-(dimethylaminomethyl)-6,7,8,9-tetrahydropyridol[1,2-a]indol-10-yl]-4-(1-methyl-3-indolyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione hydrochloride} (Ro 32-0432). Thus, Ro 32-0432 blocked mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, tested in the same neurons (5 Hz, 101% ± 2%; 1 Hz, 61% ± 8%, n = 6) (Figure 5C), and it also blocked mGluR-LTD tested in dual-patch experiments (Ro 32-0432, 99% ± 6%; control, 61% ± 8%, n = 6) (Figure 5D). These data show that PKC is involved in mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, in the perirhinal cortex.

Figure 5. Both PKC and PICK1 Are Required for mGluR-LTD, but Not NMDAR-LTD.

(A) Infusion of PKC19-31 (10 μM) blocks mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, in the same neurons (n = 5).

(B) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that PKC19-31 blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 4).

(C) Infusion of Ro 32-0432 (10 μM) blocks mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, in the same neurons (n = 5).

(D) Simultaneous dual-patch recording showing that Ro 32-0432 blocks mGluR-LTD (n = 4).

(E) Using simultaneous dual-patch-clamp recording from two neurons, mGluR-LTD is blocked in cells infused with pep2-EVKI (100 μM) but is readily induced in cells infused with pep2-SVKE (100 μM) (n = 5).

(F) Using simultaneous dual-patch-clamp recording, NMDAR-LTD is induced in cells loaded with pep2-EVKI or pep2-SVKE (n = 5). Error bars, SEM.

mGluR-LTD, but Not NMDAR-LTD, Requires PICK1

PICK1 interacts directly with the GluR2 subunit of AMPARs (Dev et al., 1999; Xia et al., 1999) and has been shown to be involved in the internalization of AMPARs (Perez et al., 2001; Hanley et al., 2002) and so is a prime candidate molecule for a role in LTD. Furthermore, it has been shown to be a Ca2+ sensor involved in NMDAR-mediated AMPAR endocytosis (Hanley and Henley, 2005). The function of PICK1 can be selectively disrupted using a peptide, pep2-EVKI (Li et al., 1999; Daw et al., 2000), that competes with its interaction for the C terminus of GluR2. Using this peptide, evidence both for (Kim et al., 2001; Terashima et al., 2008) and against (Daw et al., 2000) a role of PICK1 in NMDAR-LTD in the hippocampus and for a role of mGluR-LTD in the ventral tegmental area (Bellone and Lüscher, 2006) has been presented. We used pep2-EVKI and a noninteracting control peptide, pep2-SVKE (Daw et al., 2000), to directly compare the role of PICK1 in NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD (Figures 5E and 5F). Using simultaneous dual-patch-clamp recording from neurons within the same slice, mGluR-LTD was blocked in cells loaded with pep2-EVKI (100 μM) but was readily induced in cells loaded with pep2-SVKE (100 mM) (pep2-EVKI, 97% ± 6%; pep2-SVKE, 62% ± 7%, n = 5) (Figure 5E). In contrast, pep2-EVKI and pep2-SVKE had no effect on NMDAR-LTD (pep2-EVKI, 58% ± 4%; pep2-SVKE, 56% ± 6%, n = 5) (Figure 5F). Thus, mGluR-LTD can also be distinguished from NMDAR-LTD on the basis of its dependence on AMPAR C-terminal PDZ interactions that are likely mediated by PICK1.

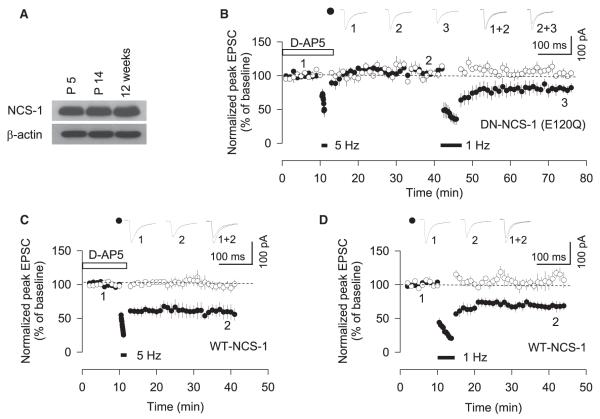

mGluR-LTD, but Not NMDAR-LTD, Requires NCS-1

Recently, Palmer et al. demonstrated that hippocalcin is involved in NMDAR-LTD in the hippocampus (Palmer et al., 2005). However, since hippocalcin is highly expressed in the hippocampus but has a limited expression in other cortical regions (Saitoh et al., 1993; Paterlini et al., 2000), we tested for the involvement of the related neuronal calcium sensor-1 (NCS-1). Like hippocalcin, NCS-1 also has a high affinity for Ca2+ but has a much more widespread distribution. First, we confirmed that NCS-1 is present in brain lysates from perirhinal cortical tissue (Figure 6A). Next, we examined the role of NCS-1 in LTD induced by both 1 Hz and 5 Hz stimulation using a dominant-negative mutant of NCS-1 (DN-NCS-1; E120Q), which has a point mutation in one of the high-affinity Ca2+-binding EF3-hand regions (Weiss et al., 2000). Inclusion of recombinant myristoylated DN-NCS-1 (40 nM) in the pipette solution had no effect on the basal amplitude of EPSCs. In the presence of DN-NCS-1, mGluR-LTD was blocked, but subsequent NMDAR-LTD was readily induced in the same neurons (5 Hz, 108% ± 8%; 1 Hz, 77% ± 9%, n = 6 [p < 0.001]) (Figure 6B). It is unlikely that inhibiting NCS-1 simply raised the threshold for inducing mGluR-LTD since 5 Hz stimulation still failed to induce LTD in the presence of DN-NCS-1 when the number of stimuli were doubled (99% ± 4%, n = 3; data not shown). In contrast to the dominant-negative, postsynaptic infusion of recombinant myristoylated wild-type NCS-1 (WT-NCS-1; 40 nM) had no effect on baseline synaptic transmission or on either form of LTD (5 Hz, 59% ± 10%, n = 6 [p < 0.001]; 1 Hz, 69% ± 7%, n = 6 [p < 0.001]) (Figures 6C and 6D). Thus, NCS-1 neither mimics nor occludes mGluR-LTD.

Figure 6. NCS-1 Is Required for mGluR-LTD, but Not NMDAR-LTD.

(A) NCS-1 is expressed in the perirhinal cortex.

(B) Postsynaptic infusion of dominant-negative NCS-1 (DN-NCS-1; 40 nM) myristoylated protein blocks mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, in the same neurons (n = 6).

(C) Postsynaptic infusion of wild-type NCS-1 (WT-NCS-1; 40 nM) has no effect on mGluR-LTD (n = 6).

(D) Postsynaptic infusion of WT-NCS-1 has no effect on NMDAR-LTD (n = 6).

Error bars, SEM. Filled symbols show the input in which 1 Hz and/or 5 Hz stimulation was delivered, and open symbols show the control input.

Because it was previously unclear whether NCS-1 played a role in synaptic plasticity, we attempted to verify its involvement using a different approach. We generated NCS-1-RNA interference (RNAi) constructs and tested their efficacy in cultured primary cortical neurons. NCS-1-RNAi, but not a control RNAi construct targeting firefly luciferase (luciferase-RNAi), greatly suppressed the expression of endogenous NCS-1 in cultured neurons, as assessed by immunocytochemistry (Figure 7A). We also tested the efficacy of NCS-1-RNAi against heterologously expressed NCS-1 by immunoblotting (Figure 7B). NCS-1-RNAi greatly suppressed the expression of NCS-1-EGFP in COS-7 cells but had no effect on the expression of NCS*-1-EGFP, an NCS-1 construct with silent mutations designed to be resistant to the NCS-1-RNAi construct.

Figure 7. Further Evidence that NCS-1 Is Required for mGluR-LTD.

(A) NCS-1-RNAi suppressed the expression of NCS-1 in primary cultured neurons.

(B) NCS-1-RNAi suppressed the expression of NCS-1-EGFP, but not NC1*-EGFP expression.

(C) Pair-wise analysis (n = 11 pairs) between transfected cells and neighboring untransfected cell shows that NCS-1 RNAi has no effect on basal excitatory synaptic transmission. AMPAR-EPSCs (left panel) and NMDAR-EPSCs (right panel) were plotted for each pair of NCS-1-RNAi-transfected and neighboring untransfected cells. Red symbol and error bars represent mean ± SEM.

(D) mGluR-LTD is blocked in neurons expressing NCS-1-RNAi (n = 7) but is unaffected in neurons expressing luciferase-RNAi (n = 7).

(E) Simultaneous patch recording showing that NMDAR-LTD is intact in both cells expressing NCS-1-RNAi (n = 7) and nontransfected control cells (n = 7).

(F) mGluR-LTD is intact in cells cotransfected with NCS*-1 and NCS-1-RNAi.

(D–F) Error bars, SEM. (D and E) Filled and open symbols show the input in which 1 Hz and/or 5 Hz stimulation was delivered.

We next transfected organotypic perirhinal cortical slice cultures at 3 days in vitro (DIV3) with NCS-1-RNAi or control luciferase-RNAi. Neurons were biolistically transfected with plasmids expressing NCS-1-RNAi or control luciferase-RNAi (plus GFP as transfection marker). At 3–5 days after RNAi transfection, we measured excitatory synaptic transmission (Figure 7C). Simultaneous recordings of EPSCs were performed from neighboring untransfected and transfected neurons (the latter identified by GFP cotransfection). There were no significant differences in AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated EPSCs between NCS-1-RNAi transfected cells and neighboring untransfected cells (EPSCAMPAR in transfected cells, 183 ± 16 pA; EPSCAMPAR in untransfected cells, 191 ± 21 pA, n = 11 pairs; EPSCNMDAR in transfected cells, 88 ± 9 pA; EPSCNMDAR in untransfected cells, 93 ± 9 pA, n = 11 pairs) (Figure 7C). We next investigated whether knockdown of NCS-1 by RNAi had any effect on LTD (Figures 7D–7F). Transfection of NCS-1-RNAi eliminated mGluR-LTD (95% ± 11%, n = 7), whereas expression of luciferase-RNAi had no effect (67% ± 7%, n = 7) (Figure 7D). In contrast, NCS-1-RNAi expression did not affect NMDAR-LTD (NCS-1-RNAi, 58% ± 7%, n = 7; untransfected cells, 62% ± 9%, n = 7) (Figure 7E). Importantly, coexpression of NCS*-1-EGFP with NCS-1 RNAi enabled full rescue of mGluR-LTD (63% ± 6%, n = 6) (Figure 7F), confirming specificity of the NCS-1 knockdown phenotype. Collectively, these results suggest that NCS-1 is specifically involved in mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD.

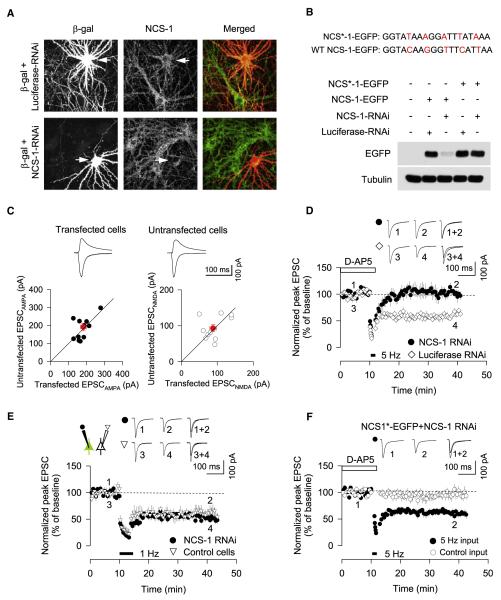

NCS-1 Interacts with PICK1 via Its BAR Domain in a Regulated Manner

The finding that both PICK1 and NCS-1 are involved in mGluR-LTD raised the question as to the relationship between these two proteins. We wondered whether, like PICK1, NCS-1 might interact with AMPA receptors or AMPA receptor-associated proteins. Therefore, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments using perirhinal cortex homogenates (Figure 8A). We found that NCS-1 was present when we immunoprecipitated with GluR1, GluR2, and, in particular, PICK1 antibodies. To further investigate the interactions, GST pull-down assays were carried out on HEK293 cell lysates, which endogenously express NCS-1 (Hui et al., 2006). The following fusion proteins were tested for their ability to pull down endogenous NCS-1: GST-GluR1ct827–907, GST-GluR2ct834–883, GST-GluR2ct834–879 (lacking the C-terminal SVKI motif: DSVKI) and GST-PICK11–412 (full-length PICK1). We found that NCS-1 selectively interacts with full-length PICK1 (Figure 8B). Next, we tested whether the two proteins can interact directly by determining whether purified recombinant His-tagged NCS-1 binds to GST-PICK1. As illustrated in Figure 8B, GST-PICK1 bound to His-tagged NCS-1, but GST alone did not. The interaction between PICK1 and NCS-1 appears to be mediated by the BAR domain of PICK1, since GST-PICK1121–354 (BAR domain) bound to NCS-1, whereas the acidic domain (GST-PICK1354–416) and PDZ domain (GST-PICK11–135) did not (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. NCS-1 Interacts with PICK1.

(A) CoIP assay using perirhinal cortex lysate. NCS-1 associates with GluR1, GluR2, and PICK1.

(B) GST pull-downs, using HEK297 cell extracts (WCL) and a His-tagged NCS-1 construct (His-NCS-1), showing that NCS-1 binds with full-length PICK1 (GST-PICK11–412). A Ponceau stain of the blot shows HEK293T cell protein lysate input into GST pull-down assays.

(C) GST pull-downs, using the His-NCS-1 construct, showing that NCS-1 binds with a BAR domain fusion protein of PICK1 (GST-PICK1121–354).

(D) PICK1 immunoprecipitation (PICK1-IP) data showing that the His-NCS-1 and GST-PICK1 interaction is Ca2+ dependent. Bar chart indicates pooled data from four independent experiments.

(E) Using simultaneous dual-patch-clamp recording from two neurons, mGluR-LTD is blocked in cells infused with GST-BAR fusion protein (50 nM) but is readily induced in cells infused with GST alone (50 nM) (n = 6).

To test whether the NCS-1-PICK1 interaction is Ca2+ dependent, PICK1-IP assays were carried out on lysates from perirhinal cortices that were treated either with Ca2+ free buffer (containing 10 mM EGTA) or 2 mM containing Ca2+ buffer. The NCS-1-PICK1 interaction was significantly stronger in the presence of Ca2+ (data not shown). To define the Ca2+ sensitivity, we compared the ability of His-NCS-1 and GST-PICK1 to bind over a range of Ca2+ concentrations. Maximal binding was observed at 50–100 μM (n = 4) (Figure 8D).

We reasoned that, if the PICK interaction with NCS-1 was necessary for mGluR-LTD, then a fusion protein of the PICK1 BAR domain (GST-PICK1-BAR) should block this form of plasticity by interfering with endogenous PICK-1 binding to NCS-1. Therefore, in dual-patch experiments, we compared the LTD, induced by 5 Hz and 1 Hz stimulation, in neurons loaded with GST-PICK1135–354 (GST-PICK1-BAR) or with GST alone. Loading of postsynaptic neurons with GST-PICK1-BAR selectively blocked mGluR-LTD (GST-PICK1-BAR, 99% ± 4%; GST, 65% ± 7%, n = 6) (Figure 8E) but, remarkably, did not affect NMDAR-LTD (GST-PICK1-BAR, 65% ± 10%; GST, 66% ± 3, n = 5) (Figure 8F). Although we cannot exclude that other BAR domain-mediated interactions are also disrupted by GST-PICK1-BAR, these data are consistent with the idea that an interaction between NCS-1 and PICK1 is required for mGluR-LTD.

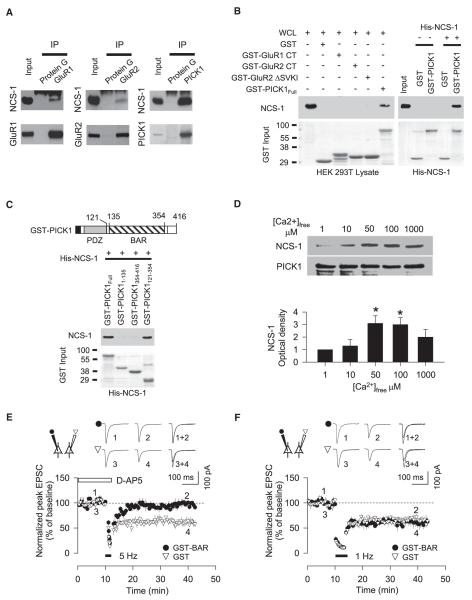

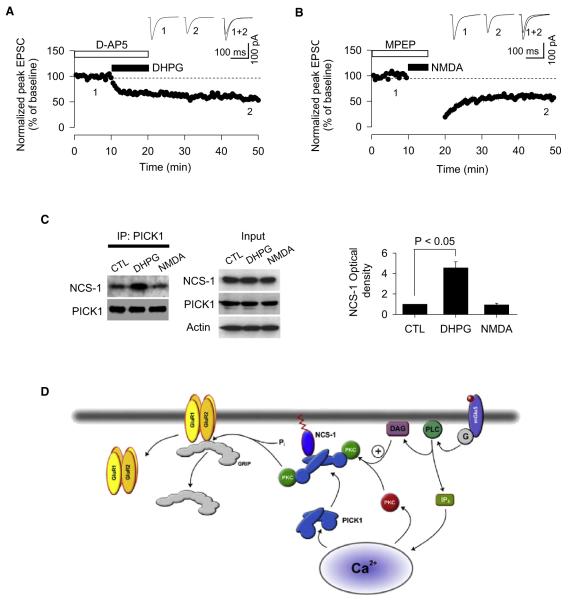

Next, we determined whether the association between NCS-1 and PICK1 is regulated, as might be expected if an interaction between these proteins is involved in mGluR-LTD. To test for this possibility, PICK1-IP assays were carried out on brain lysates prepared from slices that were treated with either DHPG (50 μM) or NMDA (50 μM). We showed that these treatments were able to induce mGluR-LTD (59% ± 5%, n = 8) (Figure 9A) and NMDAR-LTD (60% ± 5%, n = 8) (Figure 9B), respectively, in perirhinal cortex. The NCS-1-PICK1 association, measured by coimmunoprecipitation of NCS-1 with PICK1 antibodies, was much stronger in DHPG-treated slices than in control (untreated) or NMDA treated slices (Figure 9C). Therefore, our biochemical assays are consistent with the idea that a regulated PICK1-NCS-1 interaction plays a critical role in mGluR-LTD, but not in NMDAR-LTD.

Figure 9. An Association between NCS-1 and PICK1 during mGluR-LTD.

(A) Bath application of DHPG (50 μM) induces LTD (n = 8).

(B) Bath application of NMDA (50 μM) induces LTD (n = 8).

(C) PICK1-IP data from brain extracts showing that 50 μM DHPG induced a strong PICK1-NCS-1 association compared with control and 50 μM NMDA-treated brain slices. Bar chart indicates pooled data from four independent experiments performed on slices obtained from four animals.

(D) A possible role for NCS-1 in mGluR-LTD. During 5 Hz stimulation, there is activation of mGluR5, which results in stimulation of PLC to produce IP3. This results in Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, which might be the trigger for the association of NCS-1, PICK1, and PKC. Activation of PLC will also generate DAG, which, in turn, could activate the membrane-targeted PKC. The role of the NCS-1 interaction with PICK1 could, therefore, be to bring PKC into close proximity of AMPARs, where it might phosphorylate GluR2 to release GluR2 from ABP/GRIP and mobilize the receptors for removal from the synapse.

Error bars, SEM.

DISCUSSION

The primary finding of the present study is that mGluR-LTD requires the Ca2+-sensitive protein, NCS-1. In addition, we show that NCS-1 interacts with PICK1 and that the association of these two Ca2+ sensors is enhanced by the stimulation of mGluRs, indicating that they are part of a molecular machine involved in this form of LTD. In contrast, we demonstrate that NMDAR-LTD in the same neurons utilizes a different molecular cascade.

NMDAR-LTD and mGluR-LTD Involve Different Ca2+-Sensitive Mechanisms

While the primary focus of the present study was on the mechanisms underlying mGluR-LTD, we investigated NMDAR-LTD in parallel so that a direct comparison of these two forms of LTD could be made under identical experimental conditions. The finding that NMDAR-LTD involves alterations in postsynaptic Ca2+ and the calcium sensor calmodulin confirms previous studies performed primarily in the hippocampus (Mulkey et al., 1993) and is consistent with a mechanism involving the activation of a serine/threonine protein phosphatase cascade initiated by the Ca2+/calmodulin-sensitive enzyme calcineurin (Mulkey et al., 1994). Our observation that the interference of the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release process by CPA or ryanodine also blocked NMDAR-LTD builds upon some previous work in the hippocampus (Reyes and Stanton, 1996; Nishiyama et al., 2000). Presumably, the Ca2+ that permeates NMDARs triggers Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Alford et al., 1993), and this Ca2+ boost is required to activate at least one of the Ca2+-dependent steps involved in NMDAR-LTD. Less is known about the Ca2+ requirements for mGluR-LTD. While we have found that this form of LTD also requires the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, there are differences in the Ca2+ signaling mechanisms, as revealed by the differential sensitivity to blockade of the two forms of LTD by BAPTA. Consistent with independent Ca2+ signaling mechanisms was the observation that, unlike NMDAR-LTD, mGluR-LTD did not require activation of calmodulin. Conversely, mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, required activation of PKC (see also Oliet et al., 1997) and the generation of IP3.

Given that both forms of LTD involve Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, it is unlikely that the magnitude of the Ca2+ signal per se determines which form of LTD is induced but, rather, points to the existence of additional mechanisms that confer specificity toward one or other of the forms of LTD. Calmodulin could be the specificity factor for NMDAR-LTD. Indeed, the direct association of calmodulin and NMDARs (Ehlers et al., 1996) places this enzyme in a privileged position to sense the NMDAR-associated Ca2+ influx, and this could explain how the NMDAR selectively engages the protein phosphatase cascade; in which case, the Ca2+ boost from intracellular stores would be required to activate a different Ca2+ sensor required for NMDAR-LTD. In the case of NMDAR-LTD in the hippocampus, there is a requirement for the NCS protein hippocalcin (Palmer et al., 2005) and possibly PICK1 (Kim et al., 2001; Hanley and Henley, 2005; Terashima et al., 2008; but see Daw et al., 2000). Potentially, either of these sensor proteins might require Ca2+ release from intracellular stores for their activation. For mGluR-LTD, the specificity could be conferred by PKC, since the typical isoforms require both Ca2+ and diacyglycerol for their activation. Through their coupling to PLC, mGlu5 receptors are well placed to generate this dual-activation pathway. The differential sensitivity of mGluR-LTD and NMDAR-LTD to BAPTA could then be explained on the basis of the spatiotemporal Ca2+ requirements for these different Ca2+-sensitive pathways.

A Role for PICK1 in mGluR-LTD, but Not NMDAR-LTD

We explored the potential role of PICK1, since this molecule binds the C-terminal tail of GluR2 (Dev et al., 1999; Xia et al., 2000) and also interacts with the typical PKC isoform, PKCα (Staudinger et al., 1997). Furthermore, the overexpression of PICK1 leads to the internalization of GluR2-containing AMPARs (Chung et al., 2000; Perez et al., 2001; Terashima et al., 2004). Our finding that pep2-EVKI, a peptide that blocks the interaction between GluR2 and PICK1, selectively blocks mGluR-LTD suggests a role for PICK1 in this process. These data are consistent with the observations in other brain regions that PICK1 is involved in LTD triggered by the activation of mGluRs (Xia et al., 2000; Bellone and Lüscher, 2006). So how might PICK1 function in mGluR-LTD? Given that this form of LTD requires activation of PKC, it seems most likely that the action of PICK1 involves the targeting of PKC to the GluR2 subunit, though we cannot exclude a PKC-independent function for PICK1. PICK1 is a Ca2+ sensor (Hanley and Henley, 2005), and so it is plausible that the Ca2+ released from intracellular stores, following the activation of mGlu5 receptors, could be the trigger for this association.

In the same neurons, we found that blocking the interaction between PICK1 and GluR2 had no effect on NMDAR-LTD. This is consistent with the finding of Daw et al. (2000) in the hippocampus, which was also based on the acute inhibition of the GluR2-PICK1 interaction using the peptide pep2-EVKI. However, a partial inhibition of hippocampal LTD was observed using a similar peptide inhibition approach (Kim et al., 2001). Furthermore, NMDA treatment results in PICK1-dependent internalization of AMPARs in cultured hippocampal neurons (Hanley and Henley, 2005), and NMDAR-LTD in the hippocampus is eliminated by chronic expression of pep2-EVKI and by semi-acute knockdown or total knockout of PICK1 (Terashima et al., 2008). Thus, it is premature to conclude that PICK1 is not involved in NMDAR-LTD in the perirhinal cortex; rather, there is a differential sensitivity to acute disruption of the PICK1-GluR2 interaction.

A Role for NCS-1 in mGluR-LTD, but Not NMDAR-LTD

The selective involvement of PICK1 in mGluR-LTD led us to wonder whether there are other Ca2+ sensors involved in the process. NCS-1 seemed like a good candidate molecule, since, like hippocalcin, which is implicated in NMDAR-LTD in the hippocampus (Palmer et al., 2005), NCS-1 is a high-affinity Ca2+ sensor (Burgoyne, 2007), but, unlike hippocalcin, it has a much wider distribution in the brain. We verified that NCS-1 is present in perirhinal cortex and demonstrated the requirement of NCS-1 for mGluR-LTD, but not NMDAR-LTD, using both dominant-negative and RNAi approaches. Previously, NCS-1 had been shown to play a role in a variety of processes, including learning and memory (Gomez et al., 2001; Burgoyne, 2007), and this study extends that literature to suggest that NCS-1 also plays a direct role in long-term synaptic plasticity. The finding that both PICK1 and NCS-1 are required for mGluR-LTD and that the two molecules can interact raised the possibility that a direct interaction between these proteins is required for this form of LTD. Therefore, we explored the interaction using recombinant proteins and found that NCS-1 does, indeed, bind PICK1 directly. The site of interaction is the BAR domain of PICK1, which makes it difficult to design specific peptide inhibitors of the protein-protein interaction. However, consistent with the requirement for these two proteins to bind, we found that the BAR domain fusion protein of PICK1 blocked mGluR-LTD. Of course, this fusion protein could also disrupt the interaction of PICK1 with other proteins that bind to its BAR domain, such as ABP/GRIP, SNAPs, and F-actin (Hanley, 2008). It might also interfere with the ability of the BAR domain to bind to membrane phospholipids, where it may sense, or help initiate, membrane curvature during vesicle formation (Jin et al., 2006). However, the ability of the BAR domain construct to inhibit mGluR-LTD was not a nonspecific effect on AMPAR internalization, since this construct had no effect on NMDAR-LTD. This result contrasts with the partial reduction in NMDAR-LTD induced by a PICK1 mutant that cannot bind lipids (Jin et al., 2006) and the block of NMDAR-LTD following chronic inhibition of PICK1 (Terashima et al., 2008). These differences suggest that the BAR domain construct that we have used does not impair all PICK1 function but, rather, that there is a degree of selectivity in its action. In conclusion, these data are consistent with the notion that the NCS-1-PICK1 interaction is required for mGluR-LTD.

Further evidence for the selective involvement of PICK1 and NCS-1 in mGluR-LTD was the observation that stimulation of mGluRs leads to an increased association between these two proteins. A possible mechanism to account for these observations is presented in Figure 9D. We propose that activation of mGlu5 results in IP3-mediated Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and that this triggers the association of PKC and PICK1. In addition, the stimulation of mGlu5 receptors also activates translocated PKC via the formation of diacyglycerol. Since PICK1 can dimerize via its BAR domain and bind both PKC and GluR2, we speculate that PICK1 promotes PKC-dependent phosphorylation of GluR2 (Chung et al., 2000; Xia et al., 2000) to initiate the synaptic removal of AMPARs. The precise relationship between NCS-1 and PICK1 has yet to be determined. One possibility is that PICK1 and NCS-1 interact directly in response to the elevation in Ca2+. Consistent with this idea are the observations that the two recombinant proteins can bind directly in a Ca2+-dependent manner. The requirements for micromolar Ca2+ for optimal binding are consistent with the Ca2+ sensitivity of the interaction between PICK1 and GluR2 (Hanley and Henley, 2005) and suggest that PICK1 needs to adopt a Ca2+-dependent conformation for its interaction with NCS-1. The finding that the NCS-1-PICK1 association was stimulated by activation of mGluRs, but not NMDARs, implies an additional factor beyond Ca2+ that promotes the association in neurons. Conceivably, this could be the activation of PKC bound to PICK1. Since NCS-1 is associated with the plasma membrane via its myristoylated region, it might serve to target PICK1 to the vicinity of surface-expressed AMPARs to initiate their removal from the synapse. In this way, the role of NCS-1 is distinct from that of hippocalcin in NMDAR-LTD, since the latter is targeted to the plasma membrane by a Ca2+-induced conformational change that exposes its myristoylated region (Burgoyne, 2007). Further studies will be required to identify the full molecular mechanism by which PKC, PICK1, and NCS-1 interact during synaptic plasticity.

Concluding Remarks

In the present study, we have identified two independent forms of LTD that coexist in neurons in the perirhinal cortex. Thus, the two forms of LTD are activated by different classes of glutamate receptor, involve different calcium sensors and signaling cascades, and are mutually exclusive of one another. A major challenge will be to understand the functions of these two distinct forms of synaptic plasticity in the perirhinal cortex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Material

Slices of perirhinal cortex were prepared from neonatal (7 to 13 days old) Wistar rats. Experiments were carried out in accordance with the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act of 1986. Animals were sacrificed by dislocation of the neck and decapitated, and the brain was rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2) that comprised: (mM) NaCl, 124; KCl, 3; NaHCO3, 26; NaH2PO4, 1.25; CaCl2, 2; MgSO4, 1; and D-glucose, 10. A midsagittal section was made, the rostral and caudal parts of the brain were removed by single scalpel cuts made at ~45° to the dorsoventral axis, and each half was glued by its caudal end to a vibroslice stage (Leica, Nussloch, Germany). Slices (400 μm) that included perirhinal, entorhinal, and temporal cortices were stored submerged in aCSF (20°C–25°C) for 1–2 hr before transferring to the recording chamber. A single slice was placed in a submerged recording chamber (30°C –32°C, flow rate ~2 ml min−1) when required. All antagonists were made up as a stock solution and diluted to their final appropriate concentration when required.

Organotypic Brain Slice Culture

Perirhinal cortical slice cultures were prepared from 6- to 8-day-old Wistar rats. After decapitating the rat, the brain was placed immediately in cold cutting solution that comprised: (mM) Sucrose, 238; KCl, 2.5; NaHCO3, 26; NaH2PO4, 1; MgCl2, 5; D-glucose, 11; and CaCl2, 1. Perirhinal cortex slices (350 μm) were cut using a vibroslice stage (Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and placed on top of semipermeable membrane inserts (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA) in a 6-well plate containing culture medium (78.8% minimum essential medium, 20% heat-inactivated horse serum, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM D-glucose, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4, 70 μM ascorbic acid, 1 μg/ml insulin, pH adjusted to 7.3 and 320–330 mOsm). Slices were cultured in an incubator (35°C, 5% CO2) for 7–10 days in vitro (DIV) with a change of medium every 2 days. No antibiotics were used.

Electrophysiology

Stimulating electrodes were placed on either side of the rhinal sulcus. One stimulating electrode was placed dorsorostrally on the temporal cortex side (area 35/36) and one ventrocaudally on the entorhinal cortex side (area 35/entorhinal cortex) of the rhinal sulcus. Stimuli were delivered alternately to the two electrodes (each electrode stimulated at 0.033 Hz). Whole-cell recordings pipette (4–7 MΩ) solutions (280 mOsm [pH 7.2]) comprised: (mM) CsMeSO4, 130; NaCl, 8; Mg-ATP, 4; Na-GTP, 0.3; EGTA, 0.5; HEPES, 10; QX-314, 6. Neurons recorded in layer II/III were voltage clamped at −70 mV. Only cells with series resistance < 20 MΩ with a change in series resistance < 10% from the baseline were included in this study. The amplitude of excitatory post-synaptic currents (EPSCs) was measured, four consecutive responses were averaged, and these measurements were expressed relative to the normalized preconditioning baseline. To induce LTD, 200 stimuli at 5 Hz (voltage clamp at −70 mV) and/or at 1 Hz (voltage clamp at −40 mV) were delivered. D-AP5, LY367385, MPEP, and picrotoxin were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). CPA, MLCK peptide, MLCK-control peptide, and W7 were purchased from Calbiochem (California, USA.). Ascorbic acid, insulin, and BAPTA were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA).

Data were only analyzed from one slice per rat (i.e., n = number of slices = number of rats), and results from similar experiments were pooled. Single- and dual-patch recordings were carried out using an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), monitored and analyzed online, and reanalyzed offline using WinLTD program (http://www.ltp-program.com) (Anderson and Collingridge, 2007). Data pooled across slices are expressed as the mean ± SEM, and effects of conditioning stimulation were measured 20–25 min after induction of LTD. Data are expressed relative to baseline (100% = no change). Significance (p < 0.05) from baseline was tested using two-tailed t tests.

RNA Interference Constructs

For pSUPER-NCS-1-RNAi construct, the following oligonucleotides were annealed and inserted into the HindIII/BglII sites of pSUPER vector (Brummelkamp et al., 2002): 5′-GAT CCC CGG TAC AAG GGT TTC ATT AAT TCA AGA GA T TAA TGA AAC CCT TGT ACC TTT TTA-3′ and 5′-AGC TTA AAA AGG TAC AAG GGT TTC ATT AAT CTC TTG AA T TAA TGA AAC CCT TGT ACC GGG-3′. The pSUPER-Luciferase-RNAi construct was a generous gift from Dr. Huaye Zhang (Zhang and Macara, 2006).

Neuronal Culture and Transfection

Cortical neuron cultures were prepared from embryonic day (E) 18–19 rat embryos as previously described (Sala et al., 2001). Neurons were plated on coverslips coated in poly-D-lysine (30 μg/ml) and laminin (2 μg/ml) for immunocytochemistry at ~750 cells/mm2. Neurons were grown in Neurobasal medium (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with 2% B27 (GIBCO-BRL), 0.5 mM glutamine, and 12.5 μM glutamate. Neurons were transfected with plasmid DNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Glutathione S-Transferase Pull-Downs

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of C termini (CT) of GluR1, GluR2, and GluR2-ΔSVKI, as well as full-length PICK1 and its partial fragments, were previously described (Hanley et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2002). GST and GST-tagged proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 and purified with glutathione Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) according to manufacturer’s instructions. HEK293T cells were lysed in lysis/binding buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma]), and soluble cytosolic proteins were obtained by a brief centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. A 500 μg aliquot of lysate was incubated with glutathione Sepharose beads containing 100 μg of the indicated GST fusion protein in 1 ml reaction mixtures for 3 hr at 4°C. After washing four times with lysis/binding buffer, bound proteins were eluted with 2 × SDS sample buffer by boiling at 100°C for 10 min. Isolated proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-NCS-1 antiserum (1:1000 dilution, BioMol International, Exeter, UK). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using a commercial enhanced chemiluminescence reagent system (ECL kit, Amersham Biosciences).

Coimmunoprecipitations

Rat perirhinal cortical slices were treated with either DHPG (50 μM for 10 min) or NMDA (50 μM for 5 min). Crude cellular lysates were prepared in lysis/binding buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and precleared with protein G Sepharose beads for 1 hr at 4°C. Aliquots (2 mg) of precleared lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with 2 μg of rabbit polyclonal anti-PICK1 antibody (1:50 dilution, H-300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 4 hr at 4°C, and then immunocomplexes were isolated by further incubation with protein G Sepharose beads (50 μl for each reactant in 50% slurry) for 2 hr at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed four times with lysis/binding buffer and eluted with SDS sample buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and western blotting was carried out with the following antibodies: chicken polyclonal anti-NCS-1 (1:3000 dilution, Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA), goat polyclonal anti-PICK1 (1:1000 dilution, N-18, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and mouse monoclonal anti-actin (1:2000 dilution, AC-15, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). For sequential reblotting of the same blot, the membranes were stripped of the previous antibodies. Optical densities of immunoreactive bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ software (downloaded from http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). NCS-1 immunoreactivities were normalized to the quantity of PICK1 band intensity in each lane.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Royal Society (K.C.), the BBSRC (K.C. and J.L.W.), Brain Research Center of the 21st Century Frontier Research Program funded by the Korean Ministry of Science and Technology (K.C. and G.L.C.), and the MRC (G.L.C.). We thank Dr. Sang-Hyoung Lee for the GluR1 constructs, Dr. Jonathan Hanley for the PICK1 constructs, and Dr. Robert Levenson (Penn State) for the NCS-1fusion protein constructs. M.S. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. G.L.C. is a Wolfson-Royal Society fellow.

REFERENCES

- Alford S, Frenguelli BG, Schofield JG, Collingridge GL. Characterization of Ca2+ signals induced in hippocampal CA1 neurones by the synaptic activation of NMDA receptors. J. Physiol. 1993;469:693–716. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WW, Collingridge GL. Capabilities of the WinLTP data acquisition program extending beyond basic LTP experimental functions. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;162:346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artola A, Singer W. Long-term depression of excitatory synaptic transmission and its relationship to long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:480–487. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90081-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau E, Didic M, Tramoni E, Felician O, Joubert S, Sontheimer A, Ceccaldi M, Poncet M. Evolution of visual recognition memory in MCI patient. Neurology. 2004;62:1317–1322. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120548.24298.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Warburton EC, Koder T, Dolman NP, More JC, Aggleton JP, Bashir ZI, Auberson YP, Jane DE, Brown MW. The different effects on recognition memory of perirhinal kainate and NMDA glutamate receptor antagonism: Implications for underlying plasticity mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2006a;26:3561–3566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3154-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Bashir ZI, Brown MW, Warburton EC. A temporally distinct role for group I and group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in object recognition memory. Learn. Mem. 2006b;13:178–186. doi: 10.1101/lm.77806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir ZI, Jane DE, Sunter DC, Watkins JC, Collingridge GL. Metabotropic glutamate receptors contribute to the induction of long-term depression in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;239:265–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)91009-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellone C, Lüscher C. Cocaine triggered AMPA receptor redistribution is reversed in vivo by mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nn1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaizot X, Meguro K, Millien I, Baron JC, Chavoix C. Correlations between visual recognition memory and neocortical and hippocampal glucose metabolism after bilateral rhinal cortex lesion in the baboon: Implication for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:9166–9170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09166.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TVP, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA. Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of hippocampal long-term depression. Science. 1994;264:1148–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.7909958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Aggleton JP. Recognition memory: What are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;2:51–61. doi: 10.1038/35049064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD. Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: Generating diversity in neuronal Ca2+ signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:182–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K, Kemp N, Noel J, Aggleton J, Brown MW, Bashir ZI. A new form of long-term depression in the perirhinal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:150–156. doi: 10.1038/72093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K, Aggleton JP, Brown MW, Bashir ZI. An experimental test of the role of postsynaptic calcium levels in determining the synaptic strength using perirhinal cortex of rat. J. Physiol. 2001;532:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0459f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Xia J, Scannevin RH, Zhang X, Huganir RL. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 differentially regulates its interaction with PDZ domain-containing proteins. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7258–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Kehl SJ, McLennan H. Excitatory amino acids in synaptic transmission in the Schaffer collateral-commissural pathway of the rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 1983;334:33–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Chittajallu R, Bortolotto ZA, Dev KK, Duprat F, Henley JM, Collingridge GL, Isaac JT. PDZ proteins interacting with C-terminal GluR2/3 are involved in a PKC-dependent regulation of AMPA receptors at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2000;28:873–886. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev KK, Nishimune A, Henley JM, Nakanishi S. The protein kinase C alpha binding protein PICK1 interacts with short but not long form alternative splice variants of AMPA receptor subunits. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:635–644. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek SM, Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of hippocampus and effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:4363–4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers MD, Zhang S, Bernhadt JP, Huganir RL. Inactivation of NMDA receptors by direct interaction of calmodulin with the NR1 subunit. Cell. 1996;84:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M, De Castro E, Guarin E, Sasakura H, Kuhara A, Mori I, Bartfai T, Bargmann CI, Nef P. Ca2+ signaling via the neuronal calcium sensor-1 regulates associative learning and memory in C. elegans. Neuron. 2001;30:241–248. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JG. PICK1: A multi-talented modulator of AMPA receptor trafficking. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;118:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JG, Henley JM. PICK1 is a calcium-sensor for NMDA-induced AMPA receptor trafficking. EMBO J. 2005;24:3266–3278. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JG, Khatri L, Hanson PI, Ziff EB. NSF ATPase and alpha-/beta-SNAPs disassemble the AMPA receptor-PICK1 complex. Neuron. 2002;34:56–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, McHugh D, Hannan M, Zeng F, Xu SZ, Khan SU, Levenson R, Beech DJ, Weiss JL. Calcium-sensing mechanism in TRPC5 channels contributing to retardation of neurite outgrowth. J. Physiol. 2006;572:165–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Ge WP, Xu J, Cao M, Peng L, Yung W, Liao D, Duan S, Zhang M, Zia J. Lipid binding regulates synaptic targeting of PICK1, AMPA receptor trafficking, and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2380–2390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3503-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J, Ball SM, Seok H, Oh SB, Massey PV, Molnar E, Bashir ZI, Cho K. Experience-dependent modification of mechanisms of long-term depression. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:170–172. doi: 10.1038/nn1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Chung HJ, Lee HK, Huganir RL. Interaction of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2/3 with PDZ domains regulates hippocampal long-term depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11725–11730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211132798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Liu L, Wang YT, Sheng M. Clathrin adaptor AP2 and NSF interact with overlapping sites of GluR2 and play distinct roles in AMPA receptor trafficking and hippocampal LTD. Neuron. 2002;36:661–674. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Kerchner GA, Sala C, Wei F, Huettner JE, Sheng M, Zhuo M. AMPA receptor-PDZ interactions in facilitation of spinal sensory synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:972–977. doi: 10.1038/14771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G, Larson J, Kelso S, Barrionuevo G, Schottler F. Intracellular injections of EGTA block induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nature. 1983;305:719–721. doi: 10.1038/305719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Lancaster B, Zucker RS. Temporal limits on the rise in postsynaptic calcium required for the induction of long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1992;9:121–129. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler G. Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence. Psychol. Rev. 1980;87:252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita W, Marie H, Malenka RC. Distinct triggering and expression mechanisms underlie LTD of AMPA and NMDA synaptic responses. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1043–1050. doi: 10.1038/nn1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Malenka RC. Mechanisms underlying induction of homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:967–975. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90248-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Herron CE, Malenka RC. An essential role for protein phosphatases in hippocampal long-term depression. Science. 1993;261:1051–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.8394601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, Malenka RC. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488. doi: 10.1038/369486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Hong K, Mikoshiba K, Poo MM, Kato K. Calcium stores regulate the polarity and input specificity of synaptic modification. Nature. 2000;408:584–588. doi: 10.1038/35046067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SHR, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Two distinct forms of long-term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron. 1997;18:969–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CL, Lim W, Hastie PG, Toward M, Korolchuk VI, Burbidge SA, Banting G, Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Henley JM. Hippocalcin functions as a calcium sensor in hippocampal LTD. Neuron. 2005;47:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterlini M, Revilla V, Grant AL, Wisden W. Expression of the neuronal calcium sensor protein family in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;99:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Jo J, Isaac JT, Cho K. Long-term depression of kainate receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Neuron. 2006;49:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JL, Khatri L, Chang C, Srivastava S, Osten P, Ziff EB. PICK1 targets activated protein kinase Calpha to AMPA receptor clusters in spines of hippocampal neurons and reduces surface levels of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5417–5428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05417.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes M, Stanton PK. Induction of hippocampal long-term depression requires release of Ca2+ from separate presynaptic and postsynaptic intracellular stores. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5951–5960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-05951.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S, Takamatsu K, Kobayashi M, Noguichi T. Distribution of hippocalcin mRNA and immunoreactivity in rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;157:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90654-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C, Piech V, Wilson NR, Passafaro M, Liu G, Sheng M. Regulation of dendritic spine morphology and synaptic function by Shank and Homer. Neuron. 2001;31:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger J, Lu J, Olson EN. Specific interaction of the PDZ domain protein PICK1 with the COOH terminus of protein kinase C-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:32019–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima A, Cotton L, Dev KK, Meyer G, Zaman S, Duprat F, Henley JM, Collingridge GL, Isaac JT. Regulation of synaptic strength and AMPA receptor subunit composition by PICK1. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5381–5390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4378-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima A, Pelkey KA, Rah JC, Suh YH, Roche KW, Collingridge GL, McBain CJ, Isaac JT. An essential role for PICK1 in NMDA receptor-dependent bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;57:827–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torok K, Cowley DJ, Bransmeier BD, Howell S, Aitken A, Trentham DR. Inhibition of calmodulin-activated smooth-muscle myosin light-chain kinase by calmodulin-binding peptides and fluorescent (phosphodiesterase-activating) calmodulin derivatives. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6188–6198. doi: 10.1021/bi972773e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JL, Archer DA, Burgoyne RD. NCS-1 functions in a pathway regulating Ca2+ channels in adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:40082–40087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Zhang X, Staudinger J, Huganir RL. Clustering of AMPA receptors by the synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein PICK1. Neuron. 1999;22:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Chung HJ, Wihler C, Huganir RL, Linden DJ. Cerebellar long-term depression requires PKC-regulated interactions between GluR2/3 and PDZ domain-containing proteins. Neuron. 2000;28:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Macara IG. The polarity protein PAR-3 and TIAM1 cooperate in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:227–237. doi: 10.1038/ncb1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]