Abstract

Recently, a 39 amino acid peptide fragment from prostatic acid phosphatase has been isolated from seminal fluid that can enhance infectivity of the HIV virus by up to four to five orders of magnitude. PAP(248–286) is effective in enhancing HIV infectivity only when it is aggregated into amyloid fibers termed SEVI. The polyphenol EGCG (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) has been shown to disrupt both SEVI formation and HIV promotion by SEVI, but the mechanism by which it accomplishes this task is unknown. Here we show that EGCG interacts specifically with the side-chains of monomeric PAP(248–286) in two regions (K251-R257 and N269-I277) of primarily charged residues, particularly lysine. The specificity of interaction to these two sites is contrary to previous studies on the interaction of EGCG with other amyloidogenic proteins, which showed the nonspecific interaction of EGCG with exposed backbone sites of unfolded amyloidogenic proteins. This interaction is specific to EGCG as the related gallocatechin (GC) molecule, which shows greatly decreased anti-amyloid activity, exhibits minimal interaction with monomeric PAP(248–286). The EGCG binding was shown to occur in two steps, with the initial formation of a weakly bound complex followed by a pH dependent formation of a tightly bound complex. Experiments in which the lysine residues of PAP(248–286) have been chemically modified suggest the tightly bound complex is created by Schiff-base formation with lysine residues. The results of this study could aid in the development of small molecule inhibitors of SEVI and other amyloid proteins.

Keywords: Catechol, NMR, Schiff-base, ESI-MS, lysine

INTRODUCTION

The HIV virus responsible for AIDS is the source of a global pandemic with over 33 million people worldwide currently infected with the virus. The scope of AIDS pandemic sparks the question: why is HIV so prevalent in the population and transmitted so readily in vivo, while the virus itself has a very poor infection rate in vitro? One possibility is the presence of in vivo cofactors that facilitate entry of the virus, causing infection to occur at a higher rate.1,2 Recently, a cofactor has been found in human seminal fluid that could prove to be a key component in HIV transmission.3 A peptide fragment of prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP248–286, sequence GIHKQKEKSRLQGGVLVNEILNHMKRATQIPSYKKLIMY) was discovered to increase the infection rate of HIV3–7 and other enveloped viruses7,8 by several orders of magnitude when aggregated into amyloid fibrils termed SEVI.

The degree to which PAP248–286 promotes HIV infection is dependent on the conformation and aggregation state of the peptide, with the monomeric peptide being ineffective at promoting HIV infection.3,9 Since PAP248–286 is only effective in enhancing HIV infection in the aggregated SEVI form, molecules that suppress fibrillization of PAP248–286 into the active amyloid form can decrease the effective infectiousness of the HIV virus.10,11 Given the potentially high impact SEVI amyloid formation may have on the sexual transmission of HIV, a low cost SEVI inhibitor incorporated into an antiretroviral microbicide may have a substantial effect on the HIV transmission rates.6,11,12

A polyphenolic compound found in green tea (epigallocatechin-3-gallate or EGCG) inhibits the formation of SEVI fibers, disaggregates existing SEVI fibers, and blocks the SEVI mediated attachment of HIV virion to target cells and SEVI promotion of HIV infectivity.12 Polyphenolic compounds are among the most effective anti-aggregative agents discovered to date, effectively inhibiting aggregation of a broad-spectrum of amyloidogenic proteins.13 The exact mechanism by which polyphenols disrupt amyloid formation is unclear, but they appear to act at multiple points along the aggregation pathway to inhibit the elongation of existing fibers and to disrupt the formation of nuclei for further amyloid formation.14–17 EGCG has been proposed to bind to backbone sites exposed in the disordered conformation of the monomeric species of many amyloid proteins, redirecting the aggregation pathway to amorphous aggregates that are non-toxic and do not share many of the common features of amyloid-based structures.14,16 The general mechanism by which polyphenolic compounds block amyloid formation is of considerable importance, as amyloid formation is a common feature of many degenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s, type II diabetes, Parkinson’s, Creutzfield-Jacob’s, Huntington’s and others.18 Small molecules that disrupt aggregated forms of these proteins could have considerable clinical application, making a determination of the mechanism by which polyphenols disrupt aggregated conformations essential for structure-activity assays. EGCG itself has been shown to suppress both amyloid formation and associated toxicity for many of these proteins.14,16,19–21

To determine the mechanism by which EGCG disrupts SEVI amyloid formation from its precursor PAP248–286, we analyzed binding of EGCG and the related catechin GC (chemical structures shown in Fig. 1) to monomeric and small oligomeric forms of PAP248–286 by NMR and other biophysical methods. We show that, contrary to the proposed general mechanism,14 EGCG interacts specifically with the side-chains of PAP248–286. Binding occurs by a two-step mechanism in which a weakly bound complex is initially formed from monomeric PAP248–286 that is transformed in a pH dependent manner into a covalently cross-linked complex over time following the oxidation of the Met residue. The mechanism proposed in this study suggests the binding of polyphenols to amyloidogenic proteins is more complex than previously proposed and multiple interactions must be considered.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of EGCG (A) and GC (B).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

PAP248–286 obtained from Biomatik (Toronto, Ontario) was first disaggregated using a TFA (trifluoroacetic acid)/HFIP (hexafluoroisopropanol) mixture and lyophilized as described in ref. 33 for all experiments. EGCG ((−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate) and GC ((−)-gallocatechin) were purchased from Sigma. Stock solutions of EGCG and GC (50 mM and 30 mM respectively) were prepared in water and used immediately.

Thioflavin T fluorescence

The kinetics of PAP248–286 amyloid formation in the absence of EGCG or GC was measured by monitoring the increase in fluorescence intensity upon binding of the amyloid fiber to the amyloid specific dye Thioflavin T (ThT). Before the start of the experiment, PAP248–286 was solubilized in buffers containing 50 mM KPi and 25 µM ThT at two different pH values (pH 7.3 and 6.0) to achieve a final peptide concentration of 439 µM (2 mg/mL). All buffers were filtered and degassed before usage. Experiments were performed in sealed Corning 96 well clear bottom half area, nonbinding surface plates. Time traces were recorded with Biotek Synergy 2 plate reader using a 440 nm excitation filter and a 485 nm emission filter at a constant temperature of 37 °C with shaking.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For inhibition experiments using monomeric PAP248–286 solutions at pH 6.0 or 7.3 as a starting point, PAP248–286 and EGCG or GC were coincubated for 7 days at 37 °C with linear agitation of the sample at 1500 rpm, using a PAP248–286 concentration of 439 µM and a 1:5 molar ratio of EGCG or GC. After incubation, 10 µL aliquots were loaded onto Formvar-coated copper grids (Ernest F. Fullam, Inc., Latham, NY) for 2 min., washed twice with 10 µL of deionized water, and then negatively stained for 90 s with 2% uranyl acetate. Samples were imaged with Philips CM10 Transmission Electron Microscope at 8400×, 11000×, and 15000× magnification.

For disaggregation experiments, 439 µM PAP248–286 was incubated alone for 4 days at 37 °C at pH 6 or 7.3 as described above. After 4 days (pH 7.3) or 8 days (pH 6.1), EGCG or GC was added to the sample in a 1:5 molar ratio and coincubated with the resulting SEVI amyloid fibers for 4 hours. The resulting solution was then stained and imaged as described above. A comparison to control grids in the absence of EGCG or GC confirmed the presence of amyloid fibers.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR samples were prepared by dissolving 0.5 mg of lyophilized peptide in 50 mM phosphate buffer at either pH 6.0 or 7.3 containing 10% D2O. The peptide concentration was determined from the absorbance at 276 nm and was in the range of 0.3–0.4 mM for each sample.

NMR spectra were recorded at 42 °C on a 900 MHz Bruker Avance NMR spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance z-gradient cryogenic probe optimized for 1H-detection. All spectra were processed using TopSpin 2.1 software (Bruker) and analyzed using SPARKY.22 Binding experiments were performed by titration of the sample from a concentrated EGCG or GC stock solution to a 1:1 molar ratio. Backbone and side-chain assignments were performed using 2D 1H−1H TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopy) and 2D 1H−1H NOESY (nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy) recorded at two different mixing times 70 or 80 and 300 ms, respectively. Complex data points were acquired for quadrature detection in both frequency dimensions in 2D experiments and all the spectra were zero-filled in both dimensions to yield matrices of 2048 × 2048 points. Resonance assignments have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) database (accession number is 18287).

Proton diffusion NMR measurements were carried out at 499.78 MHz using the stimulated echo (STE) pulsed field gradient (PFG) pulse sequence with squared gradient pulses of constant duration (5 ms) and a variable gradient amplitude along the longitudinal axis.23 To assay possible time-dependant aggregation behavior, the PFG-NMR experiment was repeated every 2 hours on each sample for a total of 12 hours. Other parameters used in NMR experiments were as follows: a 90° pulse width of 23 µs, a spin-echo delay of 10 ms, a stimulated-echo delay of 150 ms, a recycle delay of 5 s, a spectral width of 10 kHz and 4048 data points. A saturation pulse centered at the water 1H resonance frequency was used for solvent suppression. Radio frequency pulses were phase cycled to remove unwanted echoes. All spectra were processed with a 5 Hz exponential line broadening prior to Fourier transformation and were referenced relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS at 0 ppm). The gradient strength was calibrated (G = 3.28 T m−1) from the known diffusion coefficient of HDO in D2O at 25 °C (D0 = 1.9 × 10 −9 m2 s−1).24 The diffusion coefficients were determined from a the slope of a log plot of the intensity as a function of gradient strength using the Stejskal-Tanner equation.25 The hydrodynamic radius was then calculated from the diffusion coefficient using the Einstein-Stokes relation.

SDS-PAGE and NBT (nitroblue tetrazolium) staining

PAP248–286 peptide alone and complexes of PAP248–286 with EGCG and GC in a 1:5 molar ratio were incubated at the times, temperatures, and solutions indicated in the text and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 17% acrylamide gels using Comassie blue staining. A 360 µM concentration of PAP248–286 was used. The same samples were also analyzed by NBT staining to detect protein-bound EGCG quinines.26 For NBT staining, proteins were first separated by SDS-PAGE gel and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then stained with glycinate/NBT solution (0.24 mM nitroblue tetrazolium in 2M potassium glycinate pH 10.0) for 1 hour in the dark. This resulted in a purple stain of quinone-bound protein bands. The membrane was washed and stored in 0.1 M sodium borate (pH 10.0).

Blocking ε-NH2 of Lysine in PAP248–286 using acetic anhydride

PAP248–286 peptide was first dissolved in 50 mM borate buffer (pH 8.0) and then an equimolar amount of acetic anhydride was added to the peptide solution.27 The sample was then mixed with EGCG in a 1:5 molar ratio and preincubated at room temperature for 2–3 hours before the NBT assay.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Samples of PAP248–286 for mass spectrometry analysis were first incubated at a concentration of 50 µM with EGCG at a 1:5 molar ratio for 3 days at room temperature in ammonium acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 6 or 7.3) before analysis. PAP248–286 by itself was used as a control. Mass spectra were obtained using an Orbitrap XL (ThermoFisher) electrospray-ionization (ESI) mass spectrometer. All samples were directly injected into the ESI source in positive ion mode using a flow rate of 3µl/min. The source temperature was set to 250 °C and the electrospray voltage to 4.5 kV. Before starting the experiment, the instrument was calibrated with standard compounds (per instrument manufacturer’s specification). Mass spectra were acquired continuously for 1 min and peaks between 400–2000 m/z were processed by BioworksBrowser (3.3.1 SP1, ThermoFisher) software.

RESULTS

EGCG but not GC inhibits SEVI formation at neutral and acidic pH

Hauber et al. showed that an excess of EGCG inhibits SEVI amyloid formation from PAP248–286 and slowly disaggregates existing SEVI fibers.12 These experiments were performed at pH 7.3, however, a likely microbicide containing an anti-SEVI inhibitor would have to be effective in the vaginal environment where the pH is significantly acidic, with a pH closer to 6 than 7.3.28 PAP248–286 has two histidine residues that are likely to have pKa values in this range, which may in turn effect fiber formation and/or EGCG binding. It has previously been shown that a strongly acidic environment (2% acetic acid) maintains the peptide in a monomeric state but the effect of a moderately acidic environment on SEVI fiber formation and EGCG binding is not known.29 We therefore first tested to see if EGCG would be effective at inhibiting the peptide PAP248–286 aggregation in an acidic environment (pH 6) as it is in a neutral environment (pH 7.3).

To test the aggregation kinetics, we first used the commonly used amyloid specific dye Thioflavin T. Thioflavin T (ThT) is a benzothiazole salt whose fluorescence is enhanced when it binds to grooves in the amyloid fiber running parallel to the fiber axis. As measured by ThT fluorescence, PAP248–286 fibrillizes within 53–62 hours at pH 7.3 in the absence of EGCG. PAP248–286 aggregated more slowly in the absence of EGCG at pH 6 than at pH 7.3 (Fig. S1A in the Supplementary information), although faster than in 2% acetic acid,29 most likely due to the greater electrostatic repulsion between peptides at pH 6 from the additional charge on the two histidine residues. Addition of either EGCG or GC at a 5:1 molar ratio abolishes the increase in Thioflavin T fluorescence (Fig.S1A), suggesting both compounds apparently inhibit fiber formation. Addition of EGCG and GC to preformed fibers gives an apparent dissolution half-life of 12 hours (Fig. S1B), similar to previously reported values.12

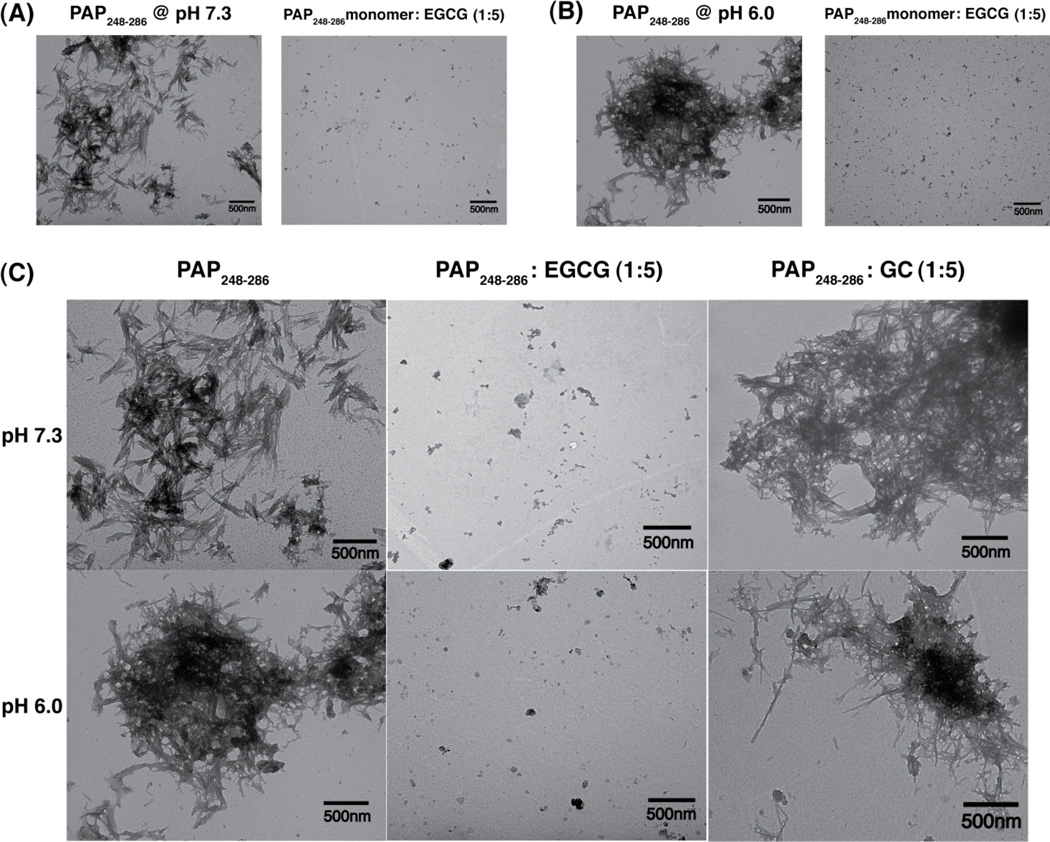

However, Thioflavin T fluorescence is known to give false positives for inhibition of fiber formation for compounds that competitively bind to the Thioflavin T binding site on the amyloid fiber without causing disaggregation of the fiber.30–32 To confirm the Thioflavin T results, transmission electron micrographs (TEM) were taken of PAP248–286 after a 96 hour incubation period. In the absence of either EGCG or GC, PAP248–286 fibrillizes to form a dense network of amyloid fibers (Fig. 2A). Coincubation of the PAP248–286 monomer with EGCG prevents the formation of this fiber network at both pH 6 and pH 7.3, confirming EGCG actually inhibits fiber formation. Examination of TEM images of preformed PAP248–286 fibers incubated with EGCG yields a similar result, confirming EGCG can also dissolve preformed PAP248–286 amyloid fibers.

Figure 2. EGCG inhibits SEVI formation from PAP248–286 and disaggregates existing fibers while the related catechin GC has a diminished effect.

(A) TEM image of PAP248–286 incubated alone for 4 days (left) and coincubated for 4 days with EGCG at a 1:5 molar ratio (right) at pH 7.3. (B) As above but for 7 days incubation at pH 6. (C) TEM images of existing SEVI amyloid fibers (left), SEVI amyloid fibers coincubated with EGCG for 5 hours (1:5 molar ratio)(center), and coincubated with GC for 5 hours (1:5 molar ratio)(right).

Comparison of the ThT and TEM results for PAP248–286 incubated with GC yields a markedly different result. While the ThT signal decreases significantly in the presence of GC, TEM images clearly show GC neither prevents fibers from forming nor dissolves preformed fibers of PAP248–286 (Figs. S2 and 2C respectively). In this case, the decrease in ThT fluorescence is a false positive for inhibition of fiber formation by GC. In summary, EGCG inhibited aggregation of PAP248–286 and disaggregated existing SEVI fibers at both pH 6 and 7.3. By contrast, the addition of the related catechin GC in a 1:5 PAP248–286 to GC molar ratio did neither (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2), in agreement with a previous report showing the absence of amyloid degradation when GC was incubated with SEVI and the lack of an inhibitory action on viral infectivity in the presence of GC.12

EGCG oligomerizes PAP248–286 immediately at pH 7.3 but not pH 6

Previous reports of the interaction of EGCG with other amyloidogenic proteins have shown the formation of off-pathway oligomers is an important mechanism for the inhibition of amyloid formation by EGCG.33 To determine if EGCG binding similarly catalyzes the oligomerization of PAP248–286, we examined the hydrodynamic radii of the PAP248–286 /EGCG complex (1:1 molar ratio) at pH 6 and 7.3 using PFG-NMR.34–36 At pH 6, the hydrodynamic radius of the PAP248–286 /EGCG complex is similar to that of PAP248–286 alone (~1.6 nm) (Fig. 3A), indicating EGCG does not cause the immediate oligomerization of PAP248–286 at pH 6. The high degree of correspondence between the hydrodynamic radii of PAP248–286 and the PAP248–286 /EGCG complex is also an indication that the size of the PAP248–286/EGCG complex is either similar to that of the PAP248–286 monomer or that EGCG does not bind the monomeric form of PAP248–286 with a high affinity at pH 6.

Figure 3. EGCG catalyzes the formation of small oligomeric species of PAP248–286 at pH 7.3 but not pH 6.

Normalized stimulated-echo intensity decays from STE (stimulated-echo) PFG 1H NMR spectra of 215 µM PAP248–286 with and without 215 µM EGCG at 37 °C in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6 (A) and pH 7.4 (B).

While the addition of EGCG had little discernible effect on the hydrodynamic radius of PAP248–286 at pH 6, at pH 7.3 a white precipitate immediately formed upon the addition of EGCG. However, a detectable signal from the PAP248–286/EGCG complex could be determined from the supernatant solution. The hydrodynamic radius of the complex formed at pH 7.3 (~3.6 nm) is substantially larger than that of PAP248–286 alone (~1.6 nm, Fig. 3B), suggesting EGCG catalyzes the fast formation of small oligomeric complexes of PAP248–286 at pH 7.3 but not at 6.

EGCG binds near the 251–257 and 269–277 regions of monomeric PAP248–286

To investigate possible binding of EGCG to the monomeric form of PAP248–286 and to identify target sites on the PAP248–286 molecule, we carried out binding studies using NMR experiments. It has previously been reported that EGCG binds randomly to exposed sites on the backbone of α-synuclein and calcitonin, 14,36 which was conjectured to be a mode of binding for most amyloid proteins.14

The addition of EGCG at 1:1 molar ratio at pH 6 caused significant broadening of resonances and substantial chemical shift perturbations for many of the residues in the 2D 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum of PAP248–286 (Fig. 4B). This finding confirms that EGCG can bind to PAP248–286 in the monomeric state and that the interaction involves considerable involvement of the side chain atoms of PAP248–286. The distribution of changes is not uniform and shows larger effects for particular amino acid types and regions of the peptide. Both the backbone and side-chain 1H resonances for residues near the central region of the peptide, such as N269, H270, M271, K272, R273 and I277, displayed a considerable shift after binding EGCG. The N-terminal region, particularly K251, Q252, K253, K255, is similarly affected. The hydrophobic center of the peptide, proposed to be a spot of amyloid initiation, 37,38 was relatively unaffected. The distribution of amino acid type is similarly non-uniform, with positively charged residues (lysines, arginine, and histidine) along with methionine showing the strongest interaction. The interaction of the positively charged side-chains with EGCG may reflect the formation of a salt bridge between EGCG and PAP248–286 (two of the phenolic groups of EGCG have pKa values near 7)39, however, we have no direct evidence of such an interaction.

Figure 4. EGCG interacts with specific residues of PAP248–286; GC minimally interacts with PAP248–286.

(A) Amino acid sequence of PAP248–286 peptide. (B) Overlaid 2D 1H−1H TOCSY spectra of PAP248–286 alone (blue) and EGCG bound to peptide (red, 1:1 molar ratio). (C) Overlaid 2D 1H−1H TOCSY spectra of GC bound to PAP248–286 (green, 1:1 molar ratio) and PAP248–286 alone (blue).

By contrast, GC, which is not an effective SEVI inhibitor,12 did not show substantial changes in the 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum (Fig. 4C). In contrast to the substantial changes seen in the 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum of EGCG/ PAP248–286, the side-chain resonances of PAP248–286 are almost unaltered by the addition of GC, indicating that GC does not have a significant interaction with the side-chains of PAP248–286.

Initial attempts at obtaining a 2D 1H−1H TOCSY spectrum of a 1:1 EGCG/PAP248–286 complex at pH 7.3 resulted in the rapid formation of a white precipitate followed by the formation of a brown solid. EGCG alone has a high propensity to oxidize at pH 7.3 and forms a brownish solution in the absence of PAP248–286. This is likely the result of auto-oxidation and aggregation of EGCG, which increases with the basicity of the solution between pH 4–8.40

EGCG forms a tightly bound PAP248–286-EGCG quinone complex after prolonged incubation

The NMR results show that the residues affected by EGCG binding were not randomly distributed but primarily concentrated among Lys, His, Arg, and Met residues. Both EGCG and GC are known to react with the nucleophilic sidechains of proteins by Schiff-base or Michelson addition.27 The formation of a precipitate when EGCG was added to PAP248–286 at high concentrations suggests the formation of covalently cross-linked products may occur, as has previously been directly detected for other flavonoids in the presence of α-synuclein and with EGCG in the presence of non-amyloidogenic proteins and peptides.27,41,42

We first tested this possibility by a NBT staining assay, which allows the detection of SDS stable, covalently or tightly bound PAP248–286 /EGCG complexes.26 In the NBT assay, the protein is first electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE than electroblotted into a membrane submerged in a solution containing NBT and glycine. EGCG reacts with glycine, generating a superoxide ion which reduces NBT to formazon generating a purple spot on the membrane.26 If EGCG is weakly bound in a conformation that is not SDS-stable, EGCG is not retained on the membrane and the formazon diffuses away during the washing step. A purple band migrating at ~ 4.5 kDa was detected when PAP248–286 was incubated with EGCG at pH 7.3 for 2 days at RT, indicating a strong SDS-resistant association with EGCG (Fig. 5A, lane 4). A corresponding band was not detected in the absence of EGCG (Fig. 5A, lane 3) or, interestingly, when PAP248–286 was incubated with EGCG at pH 6 under these conditions (Fig. 5A, lane 2). Since these conditions roughly mirror those employed in the NMR experiment, the absence of a positive NBT-staining test at pH 6 indicates that the initial EGCG / PAP248–286 complex observed by NMR is not likely to be formed by covalent attachment of ECGC to PAP248–286. However, purple bands indicating the formation of a SDS-stable EGCG-PAP248–286 complex at pH 6 became evident after a longer incubation time (2 weeks at 4° C, Fig. 5B, lane 3) but were not detected for GC (Fig.5B, lane 4).

Figure 5. The formation of a tightly bound EGCG : PAP248–286 complex is faster at pH 7.3 than at pH 6.

SDS-PAGE gel (left) and NBT stained membrane (right) of PAP248–286 alone (indicated as −) and EGCG-bound (1:5 PAP248–286/EGCG ratio) (indicated as +) at pH 6.0 and 7.3 after 2 days incubation at room temperature (A) and two weeks incubation at 4 °C (B). The presence of a purple band after NBT staining indicates the formation of a SDS stable complex.

To confirm the existence of a covalently bound complex, PAP248–286 was incubated with EGCG or GC for 3 days at room temperature and then analyzed by ESI-MS. A five-fold molar excess of EGCG and GC was used to improve sensitivity. In the absence of EGCG or GC, the mass chromatogram of PAP248–286 showed a major peak at m/z= 4550.6 and a minor peak (~10% of the total) at 4566.6 that most likely corresponds to the oxidation of M271 (Fig. S3A and B). In the presence of EGCG, the mass chromatogram showed an additional peak at m/z = 5009.6 that could be assigned to the peptide-EGCG complex (Fig. S3C and D). The intensity of the peak for the EGCG-peptide complex comprised about 35% of the total and was not affected by the pH of incubation, suggesting an equilibrium for the formation of the PAP248–286 : EGCG complex was reached after 3 days for both pH values when incubated with a five-fold excess of EGCG. The intensity of the peak for the GC-peptide complex (m/z=4857) is significantly weaker than that of EGCG (~10% compared to 35% for EGCG), indicating complex formation is more strongly favored for EGCG than GC (Fig. S3E and F). In summary, the NBT staining and ESI-MS experiments suggest the binding of EGCG to PAP248–286 is a multi-step process with covalent attachment of EGCG occurring over a period of days.

Lysines residues are critical for the interaction of PAP248–286 and EGCG

2D 1H-1H TOCSY and NOESY solution NMR experiments revealed the effect of EGCG on PAP248–286 is not random but is instead heavily concentrated on the six lysines present. To examine the role of lysine in EGCG binding in more detail, we acetylated the lysine sites of PAP248–286 by reaction with excess acetic anhydride (ESI-MS result is shown in Fig. S4). In the absence of EGCG, lysine-blocked PAP248–286 formed a sparse network of thin short fibers (Fig. 6A) after incubating for one week at pH 8. In the presence of 5 molar equivalents of EGCG, a similar network of thin short fibers can be seen in the lysine-blocked PAP248–286 sample (Fig. 6B). From these results, it is apparent that acetylation of the lysine of PAP248–286 largely blocks the inhibiting effect of EGCG on PAP248–286 amyloid formation. To see if lysine residues are also essential for the formation of the PAP248–286 covalent complex, lysine-blocked PAP248–286 was incubated with EGCG for two days at pH 8.0 and the NBT assay performed. Bands corresponding to a tightly-bound PAP248–286-EGCG complex were not observed for the lysine-blocked samples but were observed for corresponding non-lysine blocked control samples (Fig. 7B, lane 6), suggesting lysine’s involvement in cross-linking with EGCG as well.

Figure 6. Lysine residues are critical for inhibition of amyloid formation by EGCG.

TEM images of lysine blocked PAP248–286 after one week incubation at pH 8 (left) and one week incubation at pH 8 with 5 molar equivalents of EGCG (right).

Figure 7. Lysine residues are critical for EGCG binding.

(A) Overlaid 2D 1H−1H NOESY spectra of EGCG incubated with PAP248–286 bound to 400 mM SDS (magenta) and PAP248–286 in 400 mM SDS alone (black). The absence of any significant shifts suggests residues essential for binding are occluded when PAP248–286 is bound to SDS (B) SDS-PAGE gel (top) and NBT stained membrane (bottom) of PAP248–286 alone and EGCG-bound at pH 6.0 (left) and 7.3 (center) and with the lysine blocked by acetic anhydride (pH 8) (right). The absence of a purple band in the sample with the lysines blocked indicates the ε-NH2 groups of lysine are essential for the formation of a tightly bound EGCG/PAP248–286 complex.

The absence of perturbations in the NMR spectra of PAP248–286 upon the addition of EGCG after it has been bound to SDS provided additional evidence for the importance of lysines in the interaction of PAP248–286 with EGCG. In SDS micelles, PAP248–286 adopts a disordered structure on the surface of the micelle.38 While most of the backbone sites are exposed to solvent and available for binding in SDS, the lysine sidechains are buried within the micelle and shielded from interaction with EGCG.38 No changes in either the side-chain or amide backbone resonances were apparent in the 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum of PAP248–286 in 400 mM SDS at pH 6 upon the addition of EGCG (Fig. 7A). The absence of significant changes in the 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum and the absence of NBT-positive bands when the lysine sidechains are blocked are both strong indications that lysine residues are indeed essential for the formation of a tightly bound complex between PAP248–286 and EGCG.

DISCUSSION

Besides PAP248–286, EGCG both inhibits amyloid fiber formation and destabilizes existing amyloid fibers formed from a variety of other amyloid proteins including α-synuclein, Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40, IAPP, transthyretin, human and yeast prions, lysozyme, human calcitonin, κ-casein and tau.19,20,36,43–46 The molecular mechanism by which this is accomplished is not yet clear. Initially, it was proposed that EGCG diverts the normal aggregation pathway of amyloidogenic proteins into the formation of spherical unstructured aggregates, which form a non-toxic, off-pathway state that does not progress further to the amyloid form.14,16,46 On a molecular-level, EGCG has been proposed to bind to the exposed backbone of the unfolded regions of proteins, presumably blocking the association of these aggregation prone regions.14

The evidence for this mechanism primarily comes from studies of α-synuclein and Aβ1–42.14 NBT staining showed a strong, SDS stable, association of EGCG with both of these peptides and with denatured BSA but not with control proteins that were natively folded.14 Further, NMR studies of α-synuclein showed changes in the HSQC spectrum induced by EGCG were concentrated in the flexible C-terminus of the peptide, and not in the more ordered N-terminus.14 The changes were not concentrated on a particular type of residue, suggesting non-specific binding to peptide backbone rather than specific binding to the elements of the side-chains. 14

Based on the apparent generality of amyloid inhibition by EGCG, the formation of off-pathway aggregates by non-specific binding of EGCG to exposed backbone sites was proposed as a generic mechanism for amyloid inhibition by EGCG.14 However, more recent data suggests this mechanism is not entirely general. The crystal structure of EGCG bound to the tetrameric form of transthyretin reveals EGCG binds at specific sites in transthyretin, interacting with the folded transthyretin tetramer by a combination of specific hydrophobic and hydrophilic contacts with sidechains and interactions with exposed amide backbones.47 EGCG has also been shown to interact with the helical native structure of the human prion protein and with nonflexible regions of κ-casein,44 suggesting unfolded conformations are not a strict necessity for EGCG binding, in agreement with reports of EGCG binding to multiple natively folded non-amyloidogenic proteins.48 Similarly, NMR studies have suggested EGCG primarily stabilizes the monomeric structure of human calcitonin rather than redirecting the aggregation to amorphous aggregates.36

In striking contrast to the apparently random distribution of residues affected by EGCG in α-synuclein and Aβ1–42,14 EGCG primarily interacts with PAP248–286 through the side-chains of a specific set of residues. Chemical shift perturbations are concentrated at two clusters of residues, the first near the N-terminus and the second closer to the center of the peptide (Fig. 4B). Pronounced changes in particular were detected for the positively charged side-chains of lysines, suggesting a specific interaction of EGCG with this residue. The strong association of EGCG with lysine was confirmed by the absence of a strong interaction with PAP248–286 when the lysine residues of PAP248–286 were chemically blocked (Fig. 7B, lane 6). Further evidence for the importance of lysine in EGCG binding was provided by the NMR spectra of EGCG titrated to PAP248–286 bound to SDS micelles. In the SDS micelle, the positively charged lysine side-chains of PAP248–286 are strongly bound to the negatively charged headgroups of SDS and are therefore not available for EGCG binding, while the remainder of the protein is disordered and exposed to solvent.38 Virtually no change in the spectrum was observed for PAP248–286 bound to SDS when EGCG was added, indicating association of EGCG with lysine is essential for binding (Fig. 7A).

The changes in chemical shift of the initial PAP248–286/ECGC at pH 6 are reflective of a relatively weak interaction with EGCG, with exchange occurring on a fast timescale, similar to what has been observed for the initial complexes of EGCG with the amyloidogenic proteins α-synuclein and MSP2.14,43 The formation of an initially weak complex is consistent with the absence of a color reaction with NBT when PAP248–286 is incubated for 2 days at pH 6 (Fig. 5A, lane 2), indicating complex formation is initially reversible and weak enough to be removed by SDS. By contrast, NBT reacts immediately with the complex of PAP248–286 and ECGC formed at pH 7.3 (Fig 5B, lane 4). PFG NMR shows that while the hydrodynamic radius of the PAP248–286/ECGC complex formed at pH 6 is similar to that of PAP248–286 alone, the hydrodynamic radius of the complex formed at pH 7.4 is substantially larger, reflecting the oligomerization of the peptide induced by EGCG (Fig. 3). Oxidized EGCG is known to form covalently cross-linked complexes with proteins, a process influenced by a number of factors including pH, temperature, oxygen and transition metal concentrations, and the concentration of EGCG.42,49,50 Methionine residues in particular are easily oxidized by EGCG, generating hydrogen peroxide and a reactive quinone product.27 Once oxidized to the reactive quinone form, EGCG is subject to attack by the nucleophilic sidechains of lysine, histidine, and arginine residues as well as the N-terminus of the peptide to yield an acid-labile Schiff base.27,42,51,52 It should be noted, however, that the formation of a covalent EGCG-PAP248–286 complex is apparently not an absolute prerequisite for efficient inhibition of amyloid formation, as amyloid formation was inhibited by EGCG at acidic pH where formation of the covalent complex is disfavored and occurs slowly, in contrast to the relatively rapid disaggregation of amyloid fibrils observed by TEM. The eventual formation of a covalent complex is apparently also not sufficient to inhibit amyloid fiber formation, as the related compound GC does not have a strong inhibitory effect on amyloid formation even though it does slowly form a covalent or a non-covalent tightly bound complex (albeit less efficiently than EGCG) (see Fig. S3). Instead, the greater ability of EGCG to inhibit amyloid formation compared to GC is most likely due to a stronger initial association, as reflected in the stronger chemical shift perturbations observed in the NMR spectra of the EGCG-PAP248–286 complex (Fig.4).

Conclusion

Our results show that EGCG inhibits SEVI fibril formation at both neutral and acidic pH in good agreement with biophysical, biochemical and genetic data for other amyloidogenic proteins. However, the binding mechanism of EGCG to PAP248–286 deviates substantially from the proposed general model for polyphenols binding to amyloid proteins. Instead of driving the formation of large amorphous off-pathway aggregates, EGCG binds to PAP248–286 in the monomeric form, disaggregating fibrils completely to small EGCG/ PAP248–286 complexes. In addition, binding appears to be driven by interactions with the sidechains of PAP248–286 with EGCG, rather than interactions with exposed backbone sites as previously proposed. These differences may be due to the unusually high charge and low overall hydrophobicity of the PAP248–286 protein when compared to most other amyloid proteins.

While the precise mechanism by which EGCG inhibits SEVI amyloid formation is uncertain, the delay between the time in which perturbations in the NMR spectra are detected and time in which NBT staining indicates the formation of a tightly bound complex suggests the binding of EGCG to PAP248–286 is a multistep process.41 In the first step, a weakly bound, non-covalent complex is formed, most likely by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions.53,54 In the next step, a covalent complex is formed by Schiff base addition after the generation of a reactive quinone complex by autoxidation of EGCG. Further studies aimed at characterizing the interaction of EGCG with the SEVI fibrillar form of PAP248–286 are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by research funds from NIH (DK078885 to A. R.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Complete reference 2, kinetics of amyloid formation of PAP248–286 at pH 6 and 7.3 by ThT fluorescence (Fig. S1), TEM images of PAP248–286 incubated with GC (Fig. S2), ESI-MS of PAP248–286 at pH 6 and 7.3 with EGCG (Fig. S3) and ESI-MS of lysine-blocked PAP248–286 (Fig. S4). This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Doncel GF, Joseph T, Thurman AR. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011;65:292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easterhoff D, DiMaio JTM, Doran TM, Dewhurst S, Nilsson BL. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munch J, et al. Cell. 2007;131:1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roan NR, Munch J, Arhel N, Mothes W, Neidleman J, Kobayashi A, Smith-McCune K, Kirchhoff F, Greene WC. J. Virol. 2009;83:73–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01366-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim KA, Yolamanova M, Zirafi O, Roan NR, Staendker L, Forssmann WG, Burgener A, Dejucq-Rainsford N, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Greene WC, Kirchhoff F, Munch J. Retrovirology. 2010;7:55–67. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roan NR, Sowinski S, Munch J, Kirchhoff F, Greene WC. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:1861–1869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wurm M, Schambach A, Lindemann D, Hanenberg H, Standker L, Forssmann WG, Blasczyk R, Horn PA. J. Gene Med. 2010;12:137–146. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong SH, Klein EA, Das Gupta J, Hanke K, Weight CJ, Nguyen C, Gaughan C, Kim KA, Bannert N, Kirchhoff F, Munch J, Silverman RH. J. Virol. 2009;83:6995–7003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00268-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brender JR, Hartman K, Gottler LM, Cavitt ME, Youngstrom DW, Ramamoorthy A. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2474–2483. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capule CC, Brown C, Olsen JS, Dewhurst S, Yang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134:905–908. doi: 10.1021/ja210931b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen JS, Brown C, Capule CC, Rubinshtein M, Doran TM, Srivastava RK, Feng C, Nilsson BL, Yang J, Dewhurst S. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:35488–35496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauber I, Hohenberg H, Holstermann B, Hunstein W, Hauber J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:9033–9038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811827106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porat Y, Abramowitz A, Gazit E. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2006;67:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrnhoefer DE, Bieschke J, Boeddrich A, Herbst M, Masino L, Lurz R, Engemann S, Pastore A, Wanker EE. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:558–566. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladiwala ARA, Lin JC, Bale SS, Marcelino-Cruz AM, Bhattacharya M, Dordick JS, Tessier PM. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:24228–24237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Wobst H, Neugebauer K, Wanker EE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:7710–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladiwala AR, Dordick JS, Tessier PM. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;286:3209–3218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.173856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stefani M. FEBS J. 2010;277:4602–4613. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng FL, Abedini A, Plesner A, Verchere CB, Raleigh DP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8127–8133. doi: 10.1021/bi100939a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira N, Cardoso I, Domingues MR, Vitorino R, Bastos M, Bai GY, Saraiva MJ, Almeida MR. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3569–3576. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandel SA, Amit T, Weinreb O, Reznichenko L, Youdim MBH. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2008;14:352–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. San Francisco: University of California; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanner JE. J. Chem. Phys. 1970;52:2523–2526. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills R. J. Phys. Chem. 1973;77:685–688. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stejskal EO, Tanner JE. J. Chem. Phys. 1965;42:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paz MA, Fluckiger R, Boak A, Kagan HM, Gallop PM. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao D, Zhang YJ, Zhang HH, Zhong LW, Qian XH. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:1147–1157. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.TeviBenissan C, Belec L, Levy M, SchneiderFauveau V, Mohamed AS, Hallouin MC, Matta M, Gresenguet G. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1997;4:367–374. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.3.367-374.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye ZQ, French KC, Popova LA, Lednev IK, Lopez MM, Makhatadze GI. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11582–11591. doi: 10.1021/bi901709j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudson SA, Ecroyd H, Kee TW, Carver JA. FEBS J. 2009;276:5960–5972. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandrashekaran IR, Adda CG, MacRaild CA, Anders RF, Norton RS. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;513:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu KN, Wang HY, Chen CY, Wang SSS. Amino Acids. 2010;39:821–829. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladiwala ARA, Dordick JS, Tessier PM. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:3209–3218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.173856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brender JR, Nanga RPR, Popovych N, Soong R, Macdonald PM, Ramamoorthy A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soong R, Brender JR, Macdonald PM, Ramamoorthy A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7079–7085. doi: 10.1021/ja900285z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang R, Vivekanandan S, Brender JR, Abe Y, Naito A, Ramamoorthy A. J. Mol. Biol. 416:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sievers SA, Karanicolas J, Chang HW, Zhao A, Jiang L, Zirafi O, Stevens JT, Munch J, Baker D, Eisenberg D. Nature. 2011;475:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature10154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nanga RPR, Brender JR, Vivekanandan S, Popovych N, Ramamoorthy A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17972–17979. doi: 10.1021/ja908170s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumamoto M, Sonda T, Nagayama K, Tabata M. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 2001;65:126–132. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu QY, Zhang AQ, Tsang D, Huang Y, Chen ZY. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1997;45:4624–4628. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng XY, Munishkina LA, Fink AL, Uversky VN. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8206–8224. doi: 10.1021/bi900506b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii T, Ichikawa T, Minoda K, Kusaka K, Ito S, Suzuki Y, Akagawa M, Mochizuki K, Goda T, Nakayama T. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 2011;75:100–106. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandrashekaran IR, Adda CG, MacRaild CA, Anders RF, Norton RS. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5899–5908. doi: 10.1021/bi902197x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hudson SA, Ecroyd H, Dehle FC, Musgrave IF, Carver JA. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;392:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts BE, Duennwald ML, Wang H, Chung C, Lopreiato NP, Sweeny EA, Knight MN, Shorter J. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:936–946. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He J, Xing YF, Huang B, Zhang YZ, Zeng CM. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:11391–11396. doi: 10.1021/jf902664f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyata M, Sato T, Kugimiya M, Sho M, Nakamura T, Ikemizu S, Chirifu M, Mizuguchi M, Nabeshima Y, Suwa Y, Morioka H, Arimori T, Suico MA, Shuto T, Sako Y, Momohara M, Koga T, Morino-Koga S, Yamagata Y, Kai H. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6104–6114. doi: 10.1021/bi1004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maiti TK, Ghosh KS, Dasgupta S. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2006;64:355–362. doi: 10.1002/prot.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang R, Zhou WB, Jiang XH. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:2694–2701. doi: 10.1021/jf0730338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sang SM, Lee MJ, Hou Z, Ho CT, Yang CS. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2005;53:9478–9484. doi: 10.1021/jf0519055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fluckiger R, Woodtli T, Gallop PM. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;153:353–358. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grelle G, Otto A, Lorenz M, Frank RF, Wanker EE, Bieschke J. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10624–10636. doi: 10.1021/bi2012383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang SH, Liu FF, Dong XY, Sun Y. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:11576–11583. doi: 10.1021/jp1001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jobstl E, Howse JR, Fairclough JPA, Williamson MP. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:4077–4081. doi: 10.1021/jf053259f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.