Abstract

Carditis can complicate Lyme disease in an estimated <5% of cases, but cardiogenic shock is rare. We report a case of severe biventricular heart failure as a manifestation of a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in a patient with early Lyme disease following treatment with ceftriaxone.

Keywords: myocarditis, heart block, heart failure, Lyme disease, corticosteroids

CASE REPORT

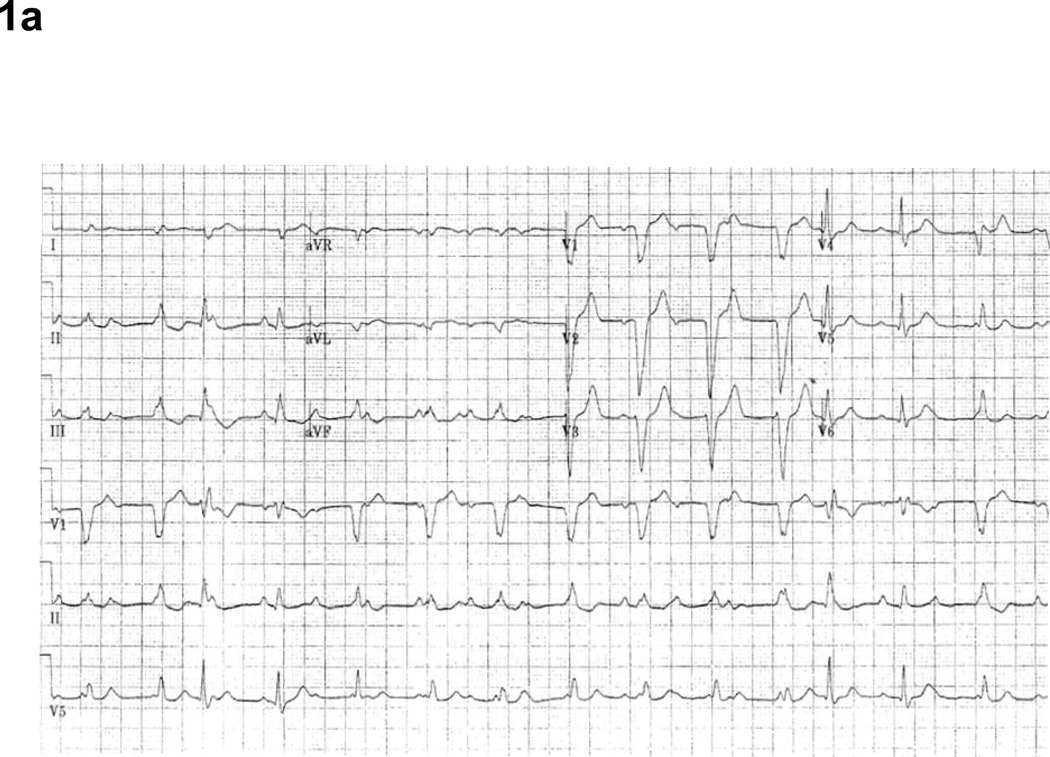

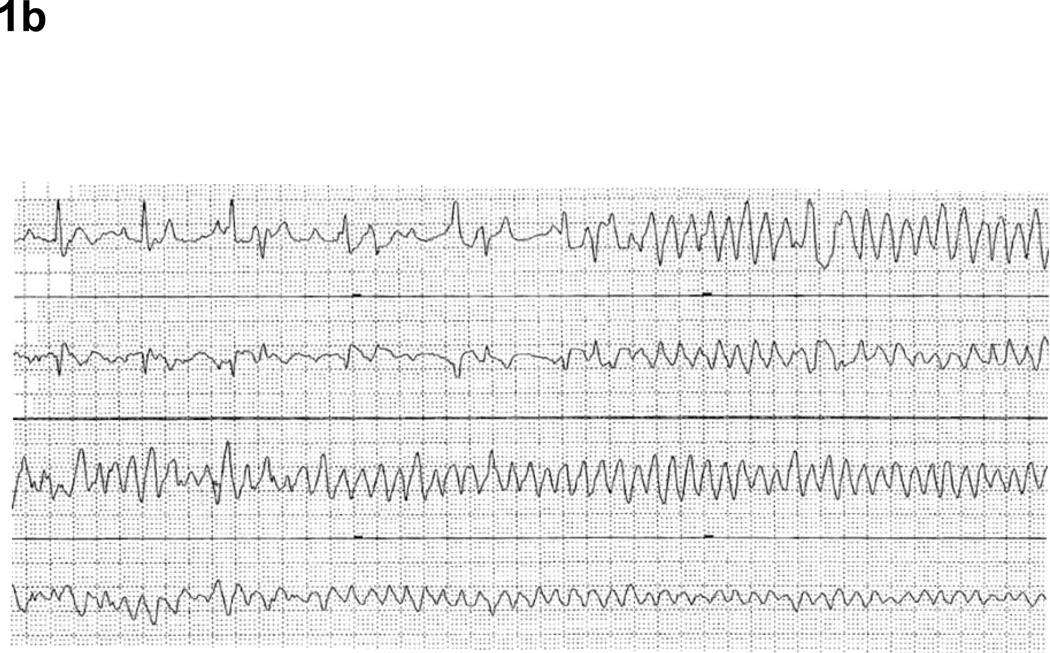

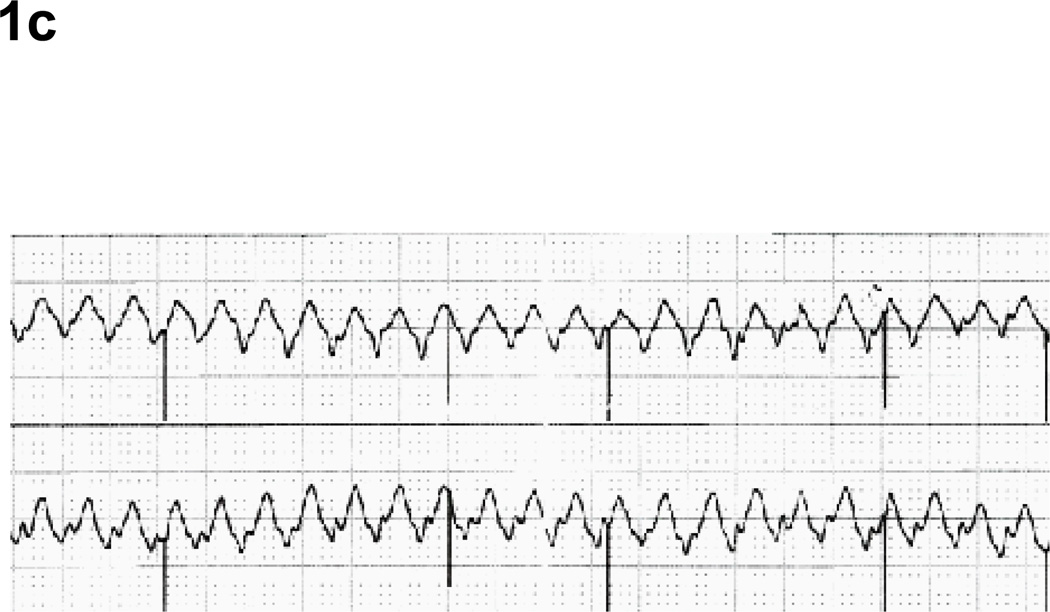

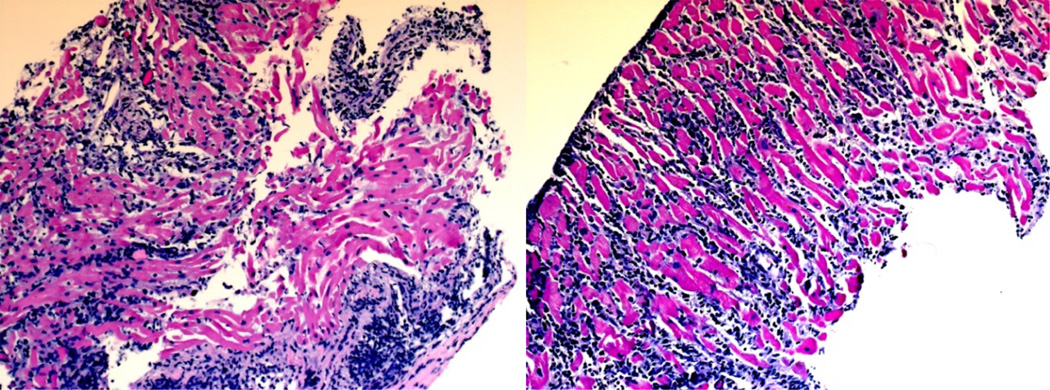

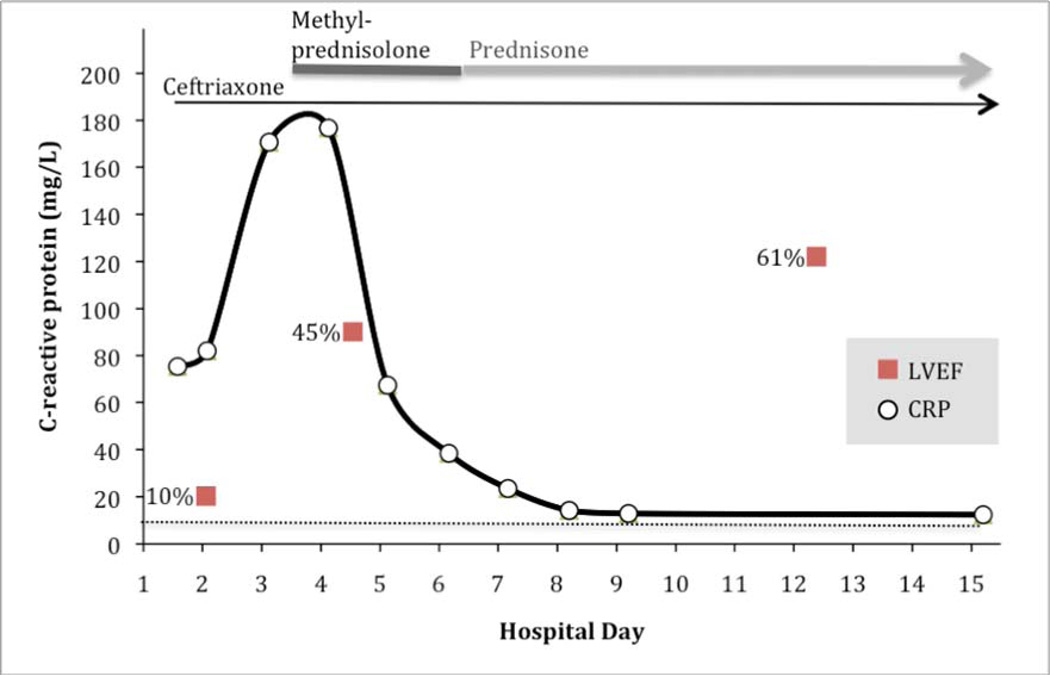

A 47-year-old woman presented with subacute fever, erythema migrans-like rash, shortness of breath, and spells of dizziness that had progressed to “blackouts”. At admission, complete atrioventricular (AV) block was present (Figure 1a), and ceftriaxone 1g was given initially for suspected Lyme disease. Within 6 hours of antimicrobial treatment, she developed polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Figure 1b). She was resuscitated with intravenous magnesium, a 150 mg bolus of amiodarone, and defibrillation. Once stabilized, echocardiography revealed severe biventricular heart failure with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 10%. Inotrope support was initiated. On hospital day 2, coronary angiography demonstrated patent epicardial coronary arteries, and endomyocardial biopsy revealed diffuse lymphocytic myocarditis (Figure 2). On day 3, methylprednisolone 1000 mg was administered daily for 3 days, followed by a 12-day taper of oral prednisone. An underlying sinus rhythm was present, but third-degree AV block persisted with intermittent 3–4 second sinus pauses, requiring placement of a temporary transvenous pacing wire. In a few instances, these had transformed into VT and ventricular flutter (Figure 1c). Intermittent failure of the temporary pacemaker to sense and capture was evident and became more frequent. These events paralleled the continued rise in serum C-reactive protein (CRP) for the first three days of hospitalization (Figure 3), and were thus attributed to diffuse, worsening myocardial inflammation.

Figure 1.

a. Electrocardiogram at admission showing complete heart block.

b. Telemetry demonstrating regression from third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) as the patient began reporting presyncopal symptoms.

c. During the first 5 hospital days, the patient had several transformations into polymorphic VT that required pacing. This rhythm strip demonstrates ventricular flutter that occurred on hospital day 3.

Figure 2.

Endomyocardial Biopsy. The tissue sample demonstrates active lymphocytic myocarditis without evidence of giant cell myocarditis or sarcoidosis (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification 200×). Additional stains for fungus and acid-fast bacilli were negative.

Figure 3.

Treatment time course in relation to serum C-reactive protein: 10% (echo), 45% (echo), 61% (cardiac magnetic resonance).

Serum ELISA and IgM Western blot were positive for Lyme disease, without evidence of co-infection. Repeat echocardiography demonstrated an LVEF of 45%, and hemodynamic support was slowly and successfully withdrawn by day 6. On day 11, oral vasodilators were initiated and intrinsic conduction had improved sufficiently to permit removal of the temporary pacer. Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors were not initiated due to intermittent bradycardia and acute tubular necrosis. Ceftriaxone was administered for 18 days, followed by oral doxycycline to complete 28 days of therapy. On day 12, cardiac magnetic resonance (MR) demonstrated normal systolic function with an LVEF of 61%. After two months, cardiac MR with gadolinium showed preserved systolic function. Neither of the cardiac MR studies revealed gross myocardial edema or fibrosis, suggesting complete recovery.

DISCUSSION

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne infection in North America, yet cardiac manifestations are relatively uncommon. A United States CDC surveillance study of Lyme disease reported cardiac findings of: palpitations (6.6%), conduction abnormalities (1.8%), myocarditis (0.9%), cardiac dysfunction (0.5%), and pericarditis (0.2%)1. From 2001–2010, 70 (0.8%) of 9,302 confirmed Lyme disease cases reported to the Minnesota Department of Health surveillance system had second- or third-degree AV block. The Infectious Diseases Society of America suggests parenteral ceftriaxone treatment for patients with second- to third-degree AV block2. Guidelines for steroid administration remain undefined, since reported cases of Lyme carditis have resolved without steroids. However, steroid implementation has been described for cases that exhibited consistent third-degree AV block for a minimum of 24–48 hours up to one week3. Meanwhile, acute heart failure in Lyme disease is very rare. The few studies that described severe heart failure were limited to patients having longstanding dilated cardiomyopathy. Among these patients, earlier ceftriaxone treatment may have been associated with complete recovery and/or improved LVEF, but the role of steroids remains unclear4.

This patient’s clinical course and treatment brought to question what caused her disease – specifically, the contribution of the foreign bacteria versus the immune response? Her sudden decompensation within hours of antimicrobial therapy, followed by 2–3 days of ongoing fevers, increasing CRP, and difficulty with transvenous pacing, all suggested a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after initiating antimicrobial therapy. Antigen release triggered the inflammatory response, the putative pathologic entity driving the ‘disease’ state of the patient’s arrhythmias and cardiogenic shock. Corticosteroids were temporally associated with substantial clinical improvement, cessation of life-threatening arrhythmias, marked decline in CRP, and restoration of near-normal LVEF.

CONCLUSION

Severe biventricular failure is a rarely described manifestation of Lyme infection, which in this case was presumably precipitated by a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Implementation of steroids should be considered as adjunctive therapy if CRP acutely rises after initiation of antimicrobial treatment of Lyme carditis. The utility of CRP as a diagnostic therapeutic marker for indicating the role of corticosteroids has not been described and should be further investigated in myocarditis.

Acknowledgments

Dr Boulware is supported by NIH NIAID K23AI073192.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

References

- 1.Ciesielski CA, Markowitz LE, Horsley R, Hightower AW, Russell H, Broome CV. Lyme disease surveillance in the united states, 1983–1986. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1989;11:S1435–S1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS, Krause PJ, Bakken JS, Strle F, Stanek G, Bockenstedt L, Fish D, Dumler S, Nadelman RB. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089–1134. doi: 10.1086/508667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver E, Pass RH, Kaufman S, Hordof AJ, Liberman L. Complete heart block due to lyme carditis in two pediatric patients and a review of the literature. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007;2:338–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2007.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnesyn SW, Diehl SC, Johnson RC, Kubo SH, Goodman JL. A prospective study of the seroprevalence of borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients with severe heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1995;76:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]