Abstract

Thiol-based redox reactions are involved in the regulation of a variety of biological functions, such as protection against oxidative stress, signal transduction and protein folding. Some proteins involved in redox regulation have been shown to modulate life span in organisms from yeast to mammals. To assess the role of thiol oxidoreductases in aging on a genome-wide scale, we analyzed the replicative life span of yeast cells lacking known and candidate thiol oxidoreductases. The data suggest the role of several pathways in regulation of yeast aging, including thioredoxin reduction, protein folding and degradation, peroxide reduction, PIP3 signaling, and ATP synthesis.

Keywords: Oxidoreductase, Antioxidant, Oxidation, Yeast, Aging, Life Span

Introduction

Many forms of molecular damage are caused by the action of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are produced as side products of cellular metabolism or are present in the evironment. The oxidative stress theory of aging predicts that the loss of antioxidant enzymes results in the oxidative damage to biomolecules and may result in shorter lifespan (Harman 1956; Sohal and Weindruch 1996). It has been shown that oxidative damage increases during replicative aging in yeast and the absence of antioxidant genes causes further accumulation of this damage (Nestelbacher et al. 2000; Grzelak et al. 2006). There are many antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutases, catalases and methionine sulfoxide reductases, that were shown to affect the replicative life span (RLS) in yeast and other organisms (Nestelbacher et al. 2000; Fabrizio et al. 2004; Unlu and Koc 2007; Radyuk et al. 2009). However, there are also contrasting data suggesting that deletion of enzymes involved in redox control does not influence RLS or even increases it in yeast. For example, increased expression of Sod1 has no effect on RLS (Kirchman et al., 1999), and overexpression of Sod2 was shown to shorten RLS (Fabrizio et al., 2004). In a different study, sod1Δ mutants had a 90 % reduction in RLS, whereas, sod2Δ cells showed no difference (Kaeberlein et al., 2005). Moreover, deletion of certain mitochondrial antioxidant genes had neutral effect on RLS in yeast (Unlu and Koc 2007). In C. elegans, while deletion of SOD2 extended life span, deletion of other SODs had no effect (Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi 2009). Additionally, manipulation of MsrB in Drosophila and yeast did not affect the life span of these organisms or affected it only under certain conditions (Koc et al. 2004; Shchedrina et al. 2009).

Protection against oxidative stress in cells is provided by both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms. Most antioxidant proteins that act in defense or repair systems are thiol oxidoreductases, which utilize cysteine (Cys) thiol groups to directly or indirectly protect the cells from deleterious effects of ROS (Fomenko and Gladyshev 2003). Many thiol oxidoreductases are characterized by the presence of CxxC, CxxS, SxxC, CxxT or TxxC motifs along with a conserved secondary structure surrounding these motifs (Fomenko and Gladyshev 2002; Fomenko and Gladyshev 2003). Redox-active Cys residues are usually well conserved during evolution, and in some organisms, the proteins with catalytic redox Cys evolved into more catalytically efficient selenoproteins, in which selenocysteine is present in place of Cys (Fomenko et al. 2007). Even though yeast cells have no selenoproteins, their Cys homologs exert the major antioxidant function in cells. Such thiol oxidoreductases can be identified by bioinformatics approaches (Fomenko et al. 2007).

Here, we analyzed a set of yeast thiol oxidoreductases, including known and predicted proteins, and determined the effect of their deletion on the replicative life span of S. cerevisiae. In our screen, we identified new genes, whose deficiency shortens life span. The data suggest the role of protein folding and degradation, ATP synthesis, peroxide reduction, PIP3 signaling and thioredoxin reduction pathways in the regulation of yeast replicative life span.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and growth

WT strains BY4741 and BY4742 (MATa his3 leu2 met15 ura3) and their isogenic deletion mutants were obtained from the yeast deletion collection set (Invitrogen). Cells were grown on YPD agar (1 % yeast extract, 2 % peptone, 2 % dextrose and 2 % agar) media. The strain lacking TRR1 gene was constructed by the single step gene replacement procedure using the HIS3 gene as the disruption and the selection marker. Transformants were selected on YNB-His (Yeast nitrogen base) medium containing 1 mM N-acetyl Cys and deletion of TRR1 gene was confirmed by PCR.

Replicative life span analyses

Cells were grown on YPD agar for 2 days prior to life span analysis. For each strain, 25 daughter cells (starter mothers) were collected and lined up by a micromanipulator on agar plates. New buds (daughters) from these virgin cells were removed and discarded as they formed. This process continued until cells ceased dividing. Life span was determined as the total number of daughter cells that each mother cell generated. In the initial screen, we analyzed the life span of five cells per strain to identify candidate mutants with altered life spans. Subsequently, 25 cells per each strain affected in the initial screen were analyzed three times.

Diamide tolerance

Overnight cultures were serially diluted to OD values of 2×10−1, 2×10−2, 2×10−3 600 , and 2×10−4. 5 μl of each dilution was dropped on YPD plates containing 2.0 mM and 2.5 mM diamide. After 2 days of incubation, plates were photographed. Experiments were repeated five times.

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity

A halo assay was performed to assess the sensitivity of cells to hydrogen peroxide (Machado et al. 1997). Briefly, cells were grown in liquid YPD overnight and their OD600 values were adjusted to 0.2. A 400 μl aliquot from each culture was transferred onto a YPD plate and dried for 30 min. Then, 5 μl of 8.8 M hydrogen peroxide was administered to the center of the plate and incubated at 30 °C overnight. Radius of the clear zone in the center of each plate was measured with a ruler. Assays were performed four times for each strain.

Analysis of the S. cerevisiae environmental stress dataset

Yeast environmental stress microarray dataset was downloaded from Stanford Yeast Stress web site (http://genome-www.stanford.edu/yeast_stress/) (Gasch et al. 2000). Data for thiol oxidoreductases and candidate genes were extracted using a Perl script.

Identification of yeast thiol oxidoreductases and candidate proteins

Known and candidate thiol oxidoreductases were identified as described in (Fomenko and Gladyshev 2002; Fomenko and Gladyshev 2003). Briefly, proteins with potential redox motifs (CxxC, CxxS, SxxC, CxxT, and TxxC) were extracted using a Perl script. Conservation of Cys in redox motifs was determined using position-specific iterated BLAST (PSI BLAST) from NCBI. Nonredundant protein database from NCBI (Sep 2008) was used in the PSI-BLAST search with the following parameters: expectation value, 0.0001; number of iterations, 3; and expectation value for multipass model, 0.01. PSI BLAST output was filtered with Perl script and Cys with more than 75% identity among homologs were further considered. PSI PRED was used for secondary structure prediction. Proteins that contained a conserved redox motif in the context of b-C/S/TxxC/S/T-a secondary structure or contained a helix downstream of the redox motif were manually analyzed for sequence homology to proteins with known function with PSI-BLAST. Metal-binding proteins were filtered based on sequence similarity to known metal-binding proteins. In addition, known yeast thiol oxidoreductases were identified using sequence similarity to known thiol oxidoreductases using NCBI BLAST standalone program with expectation value – 0.01.

Results and Discussion

Yeast thiol oxidoreductases

Table 1 shows a set of known thiol oxidoreductases in S. cerevisiae that were analyzed in these study. Interestingly, 27 of these proteins possess a thioredoxin fold. For example, the yeast proteome includes five peroxiredoxins, three glutathione peroxidases, three thioredoxins, five disulfide isomerases, and eight glutaredoxin-like proteins (five of those are monothiol glutaredoxins).

Table 1.

Yeast thiol-oxidoreductases

| Systematic Name |

Standard Name |

Redox Motif |

Redox Motif Position |

Secondary Structure |

Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YCL043C | PDI1 | CxxC, CxxC |

60, 405 | β-CGHC-α β-CGHC-α |

Protein disulfide isomerase |

| YCL035C | GRX1 | CxxC | 26 | β-CPYC-α | Glutaredoxin |

| YCR083W | TRX3 | CxxC | 54 | β-CGPC-α | Mitochondrial thioredoxin |

| YDR286C | YDR286C | CxxC | 30 | β-CGLC-α | Thioredoxin |

| YDR513W | GRX2 | CxxC | 60 | β-CPYC-α | Glutaredoxin |

| YGR029W | ERV1 | CxxC, CxxC |

29, 129 | -CRSCα, α-CNWC-α |

Mitochondrial biogenesis |

| YGR209C | TRX2 | CxxC | 30 | β-CGPC-α | Thioredoxin |

| YIL005W | EPS1 | CxxC, CxxC |

59, 199 | β-CPHC-α, β-CDKC-α |

Protein disulfide isomerase |

| YLR043C | TRX1 | CxxC | 29 | β-CGPC-α | Thioredoxin |

| YLR364W | GRX8 | CxxC | 24 | β-CPDC-α | Glutaredoxin |

| YML130C | ERO1 | CxxC, CxxC |

348, 351 | α-CVQC-α α-CDRC-α |

Involved in protein disulfide bond formation in the ER |

| YOL088C | MPD2 | CxxC | 55 | β-CQHC-α | Thiol-disulfide isomerase |

| YOR288C | MPD1 | CxxC | 58 | β-CGHC-α | Thiol-disulfide isomerase |

| YML019W | OST6 | CxxC | 77 | β-CQLC-α | Subunit of N-oligosaccharyltransferase complex |

| YOR085W | OST3 | CxxC | 72 | β-CSLC-α | Subunit of N-oligosaccharyltransferase complex |

| YDR353W | TRR1 | CxxC | 141 | -CAVC-α | Cytosolic thioredoxin reductase |

| YPR037C | ERV2 | CxxC | 120 | α-CGEC-α | Erv2 |

| YLR109W | AHP1 | SxxC | 58 | β-SPTC-α | Peroxiredoxin |

| YDR453C | TSA2 | SxxC | 44 | β- SFVC-α | Peroxiredoxin |

| YBR014C | GRX7 | CxxS | 108 | β-CPYS-α | Monothiol glutaredoxin |

| YDL010W | GRX6 | CxxS | 136 | β-CSYS-α | Monothiol glutaredoxin |

| YDR098C | GRX3 | CxxS | 211 | β-CGFS-α | Monothiol glutaredoxin |

| YER174C | GRX4 | CxxS | 171 | β-CGFS-α | Monothiol glutaredoxin |

| YPL059W | GRX5 | CxxS | 60 | β-CGFS-α | Monothiol glutaredoxin |

| YDR518W | EUG1 | CxxS, CxxS |

62, 405 | β-CLHS-α, β-CIHS-α |

Protein thiol-disulfide isomerase |

| YCL033C | MXR2 | CxxS | 157 | -CVNS- | Methionine-R sulfoxide reductase |

| YBR244W | GPX2 | CxxT | 36 | β-CGFT-α | Glutathione peroxidase |

| YGR154C | GTO1 | CxxT | 30 | β- CPFT-α | Glutathione S-transferase |

| YIR037W | HYR1 | CxxT | 35 | β- CGFT-α | Glutathione peroxidase |

| YKL026C | GPX1 | CxxT | 35 | β- CAFT-α | Glutathione peroxidase |

| YBL064C | PRX1 | TxxC | 87 | β- TPVC-α | Peroxiredoxin |

| YIL010W | DOT5 | TxxC | 103 | β- TPGC-α | Peroxiredoxin |

| YML028W | TSA1 | TxxC | 44 | β- TFVC-α | Peroxiredoxin |

| YER042W | MXR1 | CxxG | 24 | β- CFWG-α | Methionine-S sulfoxide reductase |

We previously demonstrated that conserved Cxx(C|S|T), (C|S|T)xxC (x is any amino acid) sequences, when present in the context of a simple secondary structure pattern, can be used as a predictor of thiol oxidoreductase function. This approach is not limited to specific structural folds and protein families and allows identification of known thiol oxidoreductases (Fomenko and Gladyshev 2002; Fomenko and Gladyshev 2003). We searched the S. cerevisiae protein set with this method and then filtered out metal-coordinating and structural Cys with PROSITE patterns and profiles, comparison with 3D structures from PDB and by sequence similarity to proteins known to use Cys for metal coordination. As a result, most of the known thiol oxidoreductases and 31 additional proteins with potential redox or redox-regulated Cys were identified (Table 2). Candidate thiol oxidoreductases are represented by distinct protein families and redox functions of these proteins require further experimental confirmation.

Table 2.

Yeast candidate thiol oxidoreductases

| Systematic Name |

Standard Name |

Redox Motif |

Redox Motif Position |

Secondary Structure | Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YDL034W | YDL034W | CxxC | 38 | α -CNSC- | Molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YGL211W | NCS6 | CxxC | 21 | α -CELC-α | Required for thiolation of the uridine, urmylation, invasive and pseudohyphal growth |

|

| |||||

| YJL028W | YJL028W | CxxC | 52 | α -CFAC-α | Co-localizes with ribosome, molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YJR014W | TMA22 | CxxC | 7 | -CGIC-α | Associates with ribosomes and has a putative RNA binding domain |

|

| |||||

| YKL212W | SAC1 | CxxC | 391 | β -CMDC-α | Required for phosphatidylinositol phosphate biosynthesis |

|

| |||||

| YLR271W | YLR271W | CxxC | 247 | β -CFFC-α | Molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YML041C | VPS71 | CxxC | 243, 255 | β -CSIC-, α -CVNC-α | Required for vacuolar protein sorting; nucleosome binding, chromatin remodeling |

|

| |||||

| YNL325C | FIG4 | CxxC | 466 | β -CIDC-α | Phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate 5-phosphatase activity |

|

| |||||

| YNL119W | NCS2 | CxxC | 2, 365 | CQRC-α , β -CQIC-α | Required for thiolation of the uridine;has a role in urmylation |

|

| |||||

| YNL106C | INP52 | CxxC | 445 | β -CLDC-α | Polyphosphatidylinositol phosphatase |

|

| |||||

| YOR109W | INP53 | CxxC | 420 | β -CLDC-α | Polyphosphatidylinositol phosphatase; involved in trans Golgi network |

|

| |||||

| YOR196C | LIP5 | CxxC | 184 | β -CRFC-α | Protein involved in biosynthesis of the coenzyme lipoic acid |

|

| |||||

| YOR274W | MOD5 | CxxC | 374 | α -CNVC-α | Required for biosynthesis of the modified base isopentenyladenosine in mitochondrial |

|

| |||||

| YPL107W | YPL107W | CxxC | 90 | -CVNC-α | Molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YDL077C | VAM6 | CxxC | 984 | -CPIC- | Critical role in the tethering steps of vacuolar membrane |

|

| |||||

| YNR020C | ATP23 | CxxC | 130 | -CDYC- | Putative metalloprotease of the mitochondrial inner membrane |

|

| |||||

| YGL019W | CKB1 | CxxC | 183 | -CPSC- | Casein Kinase Beta subunit; protein kinase regulator activity, cellular iron homeostasis |

|

| |||||

| YGL017W | ATE1 | CxxC | 19 | -CGYC- | Arginyltransferase activity; protein modification process |

|

| |||||

| YHR035W | YHR035W | CxxC | 47 | -CLFC- | Molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YIR026C | YVH1 | CxxC | 306 | -CPGC- | Protein phosphatase involved in vegetative growth at low temperatures |

|

| |||||

| YLR244C | MAP1 | CxxC | 36 | -CPVC- | Methionine aminopeptidase |

|

| |||||

| YOR039W | CKB2 | CxxC | 166 | -CPSC- | Beta regulatory subunit of casein kinase 2, a Ser/Thr protein kinase |

|

| |||||

| YNL239W | LAP3 | SxxC | 93 | SGRC-α | Cysteine aminopeptidase with homocysteine-thiolactonase activity |

|

| |||||

| YNL288W | CAF40 | CxxS | 181 | α -CVAS-α | Subunit of the CCR4-NOT complex involved in controlling mRNA translation |

|

| |||||

| YOR014W | RTS1 | CxxS | 583 | α -CISS-α | B-type regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A |

|

| |||||

| YER039C-A | YER039C-A | CxxS | 24 | α -CASS | Molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YFL042C | YFL042C | CxxS | 239 | -CFNS- | Molecular function and biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YOL052C | SPE2 | CxxS | 284 | -CGYS- | S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase; required for the biosynthesis of spermidine |

|

| |||||

| YMR215W | GAS3 | CxxT | 253 | β -CSGT-α | Putative 1,3-beta-glucanosyltransferase; biological process unknown |

|

| |||||

| YNL280C | ERG24 | CxxT | 381 | α -CLAT-α | C-14 sterol reductase, acts in ergosterol biosynthesis |

Replicative life span analyses of mutants

To determine whether the absence of individual thiol oxidoreductases influences life span of yeast cells, we performed replicative lifespan (RLS) analyses for 62 mutants shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Three genes shown in Table 1, PDI1, ERV1 and ERO1, are essential for viability and their mutants were not analyzed. Due to a high number of samples, only five cells from each strain were analyzed in the initial screen, and 15 mutants were identified whose life span was reduced by 20 % or more. In subsequent analyses 25 cells were followed for each selected mutant and a shortened life span of 11 mutants was confirmed by independent assays.

Thioredoxin system components

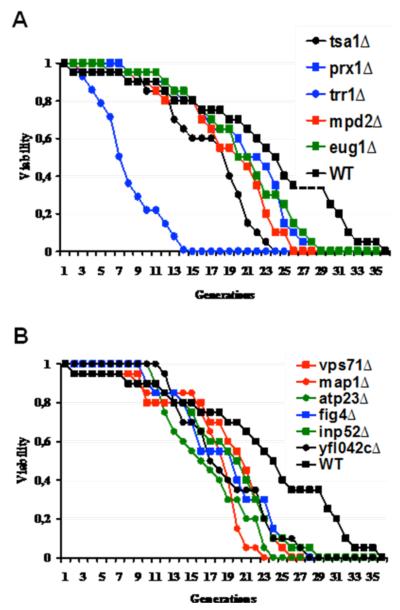

Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems are two major redox regulatory systems in cells. Deletion of two thioredoxin-dependent peroxidases, TSA1 and PRX1, decreased life span by 33 % and 17 %, respectively (Fig. 1A, Table 3). Prx1 is a mitochondrial and Tsa1 a cytoplasmic peroxidase and they both play roles in the protection against oxidative stress by reducing hydroperoxides (Chae et al. 1994; Pedrajas et al. 2000). Although both thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems have many proteins that enroll in redox homeostasis, functional redundancy is common among individual proteins and in between these two systems. Thus, it is not surprising that the absence of some of these genes did not result in obvious aging phenotypes in our screen.

Figure 1.

Replicative life span analyses of yeast cells. Life span analyses for indicated known (A) and candidate (B) thiol oxidoreductase mutants.

Table 3.

Statistical analyses of RLS analyses.

| Strain | Mean RLS |

Standart deviation |

% decrease in RLS |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 24 | 7 | ||

| tsa1 Δ | 16 | 5 | 33 | 6 × 10−8 |

| prx1 Δ | 20 | 5 | 17 | 7 × 10−3 |

| eug1 Δ | 21 | 6 | 13 | 1 × 10−3 |

| mpd2 Δ | 19 | 6 | 21 | 4 × 10−4 |

| atp23 Δ | 16 | 5 | 33 | 1 × 10−8 |

| fig4 Δ | 19 | 6 | 21 | 3 × 10−4 |

| inp52 Δ | 17 | 6 | 29 | 3 × 10−6 |

| map1 Δ | 20 | 7 | 17 | 9 × 10−3 |

| vps71 Δ | 19 | 7 | 21 | 6 × 10−4 |

| ybr042cΔ | 21 | 6 | 13 | 1 × 10−3 |

| trr1 Δ | 11 | 4 | 54 | 1 × 10−16 |

Data were derived from pair-matched experiments and compared to wild type cells by a two-tailed t test. n=70 for each strain.

An important protein in the thioredoxin system is thioredoxin reductase encoded by TRR1 gene. Deletion of TRR1 was found to be lethal in the yeast genome deletion project (Winzeler et al. 1999), however, various groups isolated trr1Δ cells and showed that its absence results in strong phenotypes, such as high sensitivity to oxidants, slow growth rate and upregulation of oxidative stress response genes (Machado et al. 1997; Carmel-Harel et al. 2001; Trotter and Grant 2002). We also isolated and analyzed the life span of trr1Δ cells to determine whether it modulates the RLS. As seen in Fig 1.A, deletion of TRR1 gene caused a 54 % reduction in the RLS which was the most significant effect observed for all genes examined in this study. Trr1 can reduce both cytosolic thioredoxins (Trx1, Trx2) and its absence leads to accumulation of oxidized forms of these proteins, altering cellular redox homeostasis. It is not surprising that deletion of neither TRX1 nor TRX2 affected the life span, probably due to redundancy in their functions. Previous studies showed that while deletion of either thioredoxin alone had no obvious phenotype, deletion of both simultaneously caused dramatic effects on DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression (Muller 1994; Koc et al. 2006).

Protein folding, degradation and processing pathways

Protein oxidation and aggregation received much attention in the previous aging studies. Misfolding of proteins and accumulation of protein aggregates was shown to be linked to aging and age-related pathologies (Carrard et al. 2002). However, the roles of protein disulfide isomerases (PDIs) in the aging process have not been studied in detail. These enzymes play important roles in protein folding. Yeast cells have five members of this family, and only Pdi1 is an essential protein. In our analyses, deletion of EUG1 and MPD2 genes decreased the life span by 13 % and 21 %, respectively (Fig. 1A, Table 3). In addition to their protein disulfide isomerase activities, Mpd2 and Eug1 may function as chaperones (Kimura et al. 2005) and overexpression of MPD2, among all protein disulfide isomerase enzymes, could compensate for the absence of PDI1 in a CxxC motif-dependent manner (Tachikawa et al. 1997; Norgaard and Winther 2001). Thus, these two proteins are important components of protein folding pathways. Previous studies showed that PDI is oxidatively modified in the liver of aged mice (Rabek et al. 2003), and its activity is decreased during aging (Nuss et al. 2008). In cells, accumulation of unfolded proteins triggers the unfolded protein response pathway and the absence of PDI seems to activate this pathway in yeast (Jonikas et al. 2009). Here, we showed that absence of two members of the PDI family, Eug1 and Mpd2, decreased the life span of cells probably due to accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins.

In addition to PDIs, we analyzed several other proteins implicated in protein folding, degradation or processing. VPS71 gene product has been shown to participate in vacuolar protein sorting (Bonangelino et al. 2002) and chromatin remodeling (Wu et al. 2005). Its deletion led to a 21 % decrease in life span. Vps71 is a nucleosome binding component of the Swir1 complex, which replaces histone variant H2AZ for H2A (Wu et al. 2005). MAP1 gene encodes a methionine aminopeptidase that plays a role in co-translational removal of N-terminal methionines from nascent polypeptides (Chang et al. 1990). Even though physiological function of Map1 is not clear, deficiency in this protein decreased the average life span by 17 % (Fig. 1B).

Assembly of ATP synthase

Cellular ATP generation depends on the correct assembly of F0F1-ATP synthase, which is made of both nuclear and mitochondria-encoded proteins. Atp23 is a peptidase for the maturation of F0-subunit Atp6. Apart from its peptidase activity, Atp23 plays a role in association of Atp6 with Atp9 oligomers in the assembly of F0F1 ATP synthase (Osman et al. 2007). Deficiency in this protein decreased the life span of yeast cells by 33 % (Fig. 1B). Cells lacking ATP23 gene were petite, had defective ATPase activity and showed deficiency in many cytochromes (Zeng et al. 2007). Since the deletion of ATP23 resulted in pleiotropic effects in mitochondria, it is not surprising that the absence of this gene also resulted in a shorter RLS.

PIP signaling system

Two of the short-living mutants lacked FIG4 and INP52 genes, both of which play a role in phosphatidylinositol signaling system. Deletion of FIG4 and INP52 decreased the average life span by 21 % and 29 %, respectively (Fig. 1B). Products of both genes contain Sac phosphatase and 5-phosphatase domains and control diverse cellular functions, such as mating response, endocytosis and exocytosis (Hughes et al. 2000). Fig4 is a phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate phosphatase required for efficient mating, membrane trafficking, and response to osmotic shock (Erdman et al. 1998; Gary et al. 2002), and Inp52 is a polyphosphatidylinositol phosphatase involved in endocytosis and hyperosmotic stress (Stolz et al. 1998). Since these genes participate in different pathways, it is not clear which of their functions limit the life span.

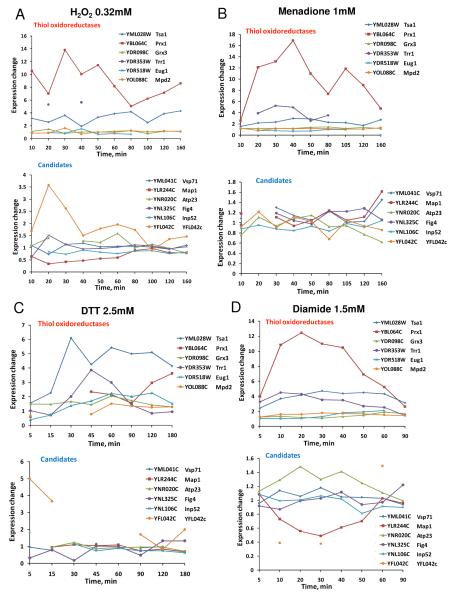

Figure 4.

Transcriptional expression analyses of oxidoreductases in response to redox stresses. (A) Regulation of thiol oxidoreductase gene expression by 0.32 mM hydrogen peroxide. B) Regulation by 1 mM menadione. (C) Regulation by 2.5 mM DTT. (D) Regulation by 1.5 mM diamide.

Genes with unknown functions

Absence of YFL042c decreased life span by 13 % (Fig. 1B). YFL042c encodes a 76 kDa protein of unknown function.

Oxidative stress tolerance of short living mutants

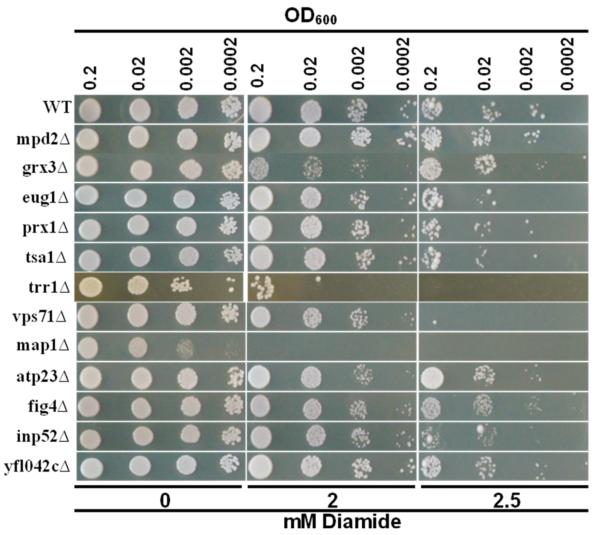

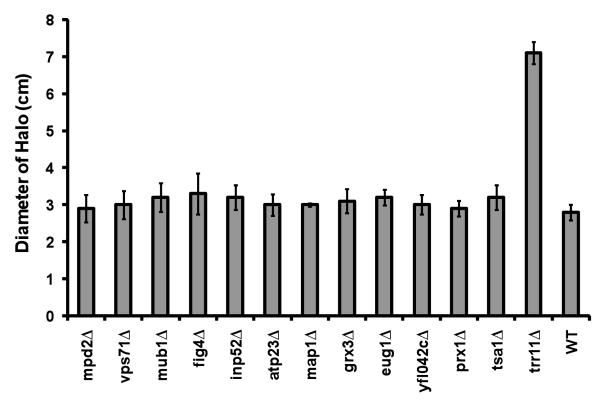

To better understand the underlying reasons for a short life span of exained mutant cells, we analyzed these mutants for sensitivity to oxidants, diamide and hydrogen peroxide. Diamide sensitivity of mutants was investigated by a spotting assay. As seen in Fig. 2, deletion of MAP1, TRR1 and VPS71genes resulted in the greatest sensitivity to diamide. The other mutants were either not sensitive or showed marginal sensitivity. To characterize the effect of hydrogen peroxide, logarithmically growing cells were spread on YPD plates, and a drop of hydrogen peroxide was administered at the center of the plates. The diameter of the clear zone in which growth was suppressed was measured for each strain after overnight incubation and results were summarized in Fig. 3 and Table 4. Surprisingly, most of the mutants were not sensitive to hydrogen peroxide treatment and they formed halos 3-3.5 centimeters in diameter. Only trr1Δ cells were very sensitive to hydrogen peroxide and formed 7 centimeter-halos (Fig. 3, Table 4).

Figure 2.

Diamide sensitivity assay. Overnight cultures were diluted to indicated densities and 5 μl of each cell suspension was spotted on plates containing shown amounts of diamide. Cells were grown for 3 days and plates were photographed. Experiments were repeated five times and a represantative picture is shown.

Figure 3.

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assay. Sensitivity of cells to hydrogen peroxide was determined by a halo assay in which 5 μl of 8.8 M H2O2 applied to the center of the YPD plates which were preinoculated with cells. The diameter of zones in which cell growth was suppressed was measured. Each strain was tested four times, and the bars show the standart errors of the mean.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of hydrogen peroxide halo assay

| Strain | Mean Diameter |

Standart deviation |

% Change |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 2.8 | 0.2 | ||

| tsa1 Δ | 3.2 | 0.3 | 14 | 0.06 |

| prx1 Δ | 3.0 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.32 |

| eug1 Δ | 3.2 | 0.2 | 14 | 0.01 |

| mpd2 Δ | 2.9 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.56 |

| atp23 Δ | 3.0 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.23 |

| fig4 Δ | 3.4 | 0.5 | 20 | 0.07 |

| inp52 Δ | 3.2 | 0.3 | 15 | 0.04 |

| map1 Δ | 3.1 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.04 |

| vps71 Δ | 3.0 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.37 |

| ybr042c Δ | 3.0 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.20 |

| trr1 Δ | 7.1 | 0.3 | 154 | 0.00 |

Statistical anaylyses were done for comparisons against wild type cells. Data were compared by a two-tailed t test. n=4 for each strain.

Apart from sensitivity of the mutants to oxidants, we extracted and analyzed data from a publicly available dataset (Gasch et al. 2000) to asses the expression profiles of these genes in response to different redox stressors, including hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 4A), menadione (Fig. 4B), DTT (Fig. 4C) and diamide (Fig. 4D). In all stress conditions, expression of PRX1, TRR1 and TSA1 genes was upregulated. In addition, in response to hydrogen peroxide treatment, YCL042c expression was increased.

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the effects of deletion of known and candidate thiol oxidoreductases on replicative life span of S. cerevisiae. Most functions relevant to redox homeostasis are conducted by thiol oxidoreductases, and we reasoned that the absence of these genes may disrupt the redox balance of cells and affect their life span. In addition to 31 known thiol oxidoreductases, we analyzed 31 proteins with potential thiol oxidoreductase functions. Surprisingly, the RLS screen revealed that only 11 mutants had a shorter life span, while none of them had a longer RLS. These mutants were deficient in thiol oxidoreductase components of protein folding and degradation, peroxide reduction, PIP3 signaling, thioredoxin reduction, and ATP synthesis pathways.

There could be many reasons why the deficiency in most of thiol oxidoreductase genes did not lead to a change in RLS. First, redundancy in yeast thiol oxidoreductases is very common. For example, the core of the yeast set of thiol oxidoreductases consists of five peroxiredoxins, three glutathione peroxidases, three thioredoxins, five protein disulfide isomerases, and eight glutaredoxin-like proteins. Thus, absence of individual genes could be compensated by their functional homologs. Analyses of multiple gene mutants, when viable, for each thiol oxidoreductase family should be performed to assess the role of each family/pathway in the RLS. Second, many of these oxidoreductases are regulated by transcription factors Yap1 or Skn7 and a compensatory upregulation of other proteins induced by these transcription factors may help cells to cope with stress conditions more efficiently. Third, some mutants may have escaped detection in the initial screen. Additionally, deletion of PDI1, ERV1 and ERO1 is lethal, and we were not able to include these essential genes in our screen.

In this work, we did not study the mechanisms of life span decrease in oxidoreductase mutants, and our data do not necessarily exclude the possibility that the shortened life span of mutants may be an indirect effect of mutation. Thus, the role of these genes and pathways in yeast aging should be further investigated.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Biotechnology Center and Biological Mass Spectra facility of Izmir Institute of Technology for help with instrumentation. This work was supported by DPT-2003K120690 and TÜBA-GEBỊP grants (to AK) and by NIH AG021518 (to VNG).

Abbreviations

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RLS

Replicative life span

- Cys

cysteine

- Trx

thioredoxin

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

References

- Bonangelino CJ, Chavez EM, Bonifacino JS. Genomic screen for vacuolar protein sorting genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(7):2486–501. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel-Harel O, Stearman R, Gasch AP, Botstein D, Brown PO, Storz G. Role of thioredoxin reductase in the Yap1p-dependent response to oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39(3):595–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrard G, Bulteau AL, Petropoulos I, Friguet B. Impairment of proteasome structure and function in aging. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34(11):1461–74. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae HZ, Chung SJ, Rhee SG. Thioredoxin reductase-dependent peroxide reductase from yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:27670–27678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YH, Teichert U, Smith JA. Purification and characterization of a methionine aminopeptidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(32):19892–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman S, Lin L, Malczynski M, Snyder M. Pheromone-regulated genes required for yeast mating differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(3):461–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Battistella L, Vardavas R, Gattazzo C, Liou LL, Diaspro A, Dossen JW, Gralla EB, Longo VD. Superoxide is a mediator of an altruistic aging program in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(7):1055–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomenko DE, Gladyshev VN. CxxS: fold-independent redox motif revealed by genome-wide searches for thiol/disulfide oxidoreductase function. Protein Sci. 2002;11(10):2285–96. doi: 10.1110/ps.0218302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomenko DE, Gladyshev VN. Identity and functions of CxxC-derived motifs. Biochemistry. 2003;42(38):11214–25. doi: 10.1021/bi034459s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomenko DE, Xing W, Adair BM, Thomas DJ, Gladyshev VN. High-throughput identification of catalytic redox-active cysteine residues. Science. 2007;315(5810):387–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1133114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary JD, Sato TK, Stefan CJ, Bonangelino CJ, Weisman LS, Emr SD. Regulation of Fab1 phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase pathway by Vac7 protein and Fig4, a polyphosphoinositide phosphatase family member. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(4):1238–51. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G, Botstein D, Brown PO. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(12):4241–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzelak A, Macierzynska E, Bartosz G. Accumulation of oxidative damage during replicative aging of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(9):813–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11(3):298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes WE, Cooke FT, Parker PJ. Sac phosphatase domain proteins. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 2):337–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonikas MC, Collins SR, Denic V, Oh E, Quan EM, Schmid V, Weibezahn J, Schwappach B, Walter P, Weissman JS, Schuldiner M. Comprehensive characterization of genes required for protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2009;323(5922):1693–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1167983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK. Genes determining yeast replicative life span in a long-lived genetic background. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(4):491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Hosoda Y, Sato Y, Kitamura Y, Ikeda T, Horibe T, Kikuchi M. Interactions among yeast protein-disulfide isomerase proteins and endoplasmic reticulum chaperone proteins influence their activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(36):31438–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchman PA, Kim S, Lai CY, Jazwinski SM. Interorganelle signaling is a determinant of longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;152:179–190. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc A, Gasch AP, Rutherford JC, Kim HY, Gladyshev VN. Methionine sulfoxide reductase regulation of yeast lifespan reveals reactive oxygen species-dependent and -independent components of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(21):7999–8004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc A, Mathews CK, Wheeler LJ, Gross MK, Merrill GF. Thioredoxin is required for deoxyribonucleotide pool maintenance during S phase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(22):15058–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado AK, Morgan BA, Merrill GM. Thioredoxin reductase-dependent inhibition of MCB cell cycle box activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17045–17054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller EGD. Deoxyribonucleotides are maintained at normal levels in a yeast thioredoxin mutant defective in DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:24466–24471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestelbacher R, Laun P, Vondrakova D, Pichova A, Schuller C, Breitenbach M. The influence of oxygen toxicity on yeast mother cell-specific aging. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard P, Winther JR. Mutation of yeast Eug1p CXXS active sites to CXXC results in a dramatic increase in protein disulphide isomerase activity. Biochem J. 2001;358(Pt 1):269–74. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss JE, Choksi KB, DeFord JH, Papaconstantinou J. Decreased enzyme activities of chaperones PDI and BiP in aged mouse livers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365(2):355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman C, Wilmes C, Tatsuta T, Langer T. Prohibitins interact genetically with Atp23, a novel processing peptidase and chaperone for the F1Fo-ATP synthase. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(2):627–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrajas JR, Miranda-Vizuete A, Javanmardy N, Gustafsson JA, Spyrou G. Mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae contain one-conserved cysteine type peroxiredoxin with thioredoxin peroxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):16296–301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabek JP, Boylston WH, 3rd, Papaconstantinou J. Carbonylation of ER chaperone proteins in aged mouse liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305(3):566–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radyuk SN, Michalak K, Klichko VI, Benes J, Rebrin I, Sohal RS, Orr WC. Peroxiredoxin 5 confers protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis and also promotes longevity in Drosophila. Biochem J. 2009;419(2):437–45. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchedrina VA, Vorbruggen G, Lee BC, Kim HY, Kabil H, Harshman LG, Gladyshev VN. Overexpression of methionine-R-sulfoxide reductases has no influence on fruit fly aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130(7):429–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273(5271):59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz LE, Huynh CV, Thorner J, York JD. Identification and characterization of an essential family of inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases (INP51, INP52 and INP53 gene products) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;148(4):1715–29. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachikawa H, Funahashi W, Takeuchi Y, Nakanishi H, Nishihara R, Katoh S, Gao XD, Mizunaga T, Fujimoto D. Overproduction of Mpd2p suppresses the lethality of protein disulfide isomerase depletion in a CXXC sequence dependent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239(3):710–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter EW, Grant CM. Thioredoxins are required for protection against a reductive stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46(3):869–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unlu ES, Koc A. Effects of deleting mitochondrial antioxidant genes on life span. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:505–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk JM, Hekimi S. Deletion of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase sod-2 extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(2):e1000361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, Chu AM, Connelly C, Davis K, Dietrich F, Dow SW, El Bakkoury M, Foury F, Friend SH, Gentalen E, Giaever G, Hegemann JH, Jones T, Laub M, Liao H, Liebundguth N, Lockhart DJ, Lucau-Danila A, Lussier M, M’Rabet N, Menard P, Mittmann M, Pai C, Rebischung C, Revuelta JL, Riles L, Roberts CJ, Ross-MacDonald P, Scherens B, Snyder M, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Veronneau S, Voet M, Volckaert G, Ward TR, Wysocki R, Yen GS, Yu K, Zimmermann K, Philippsen P, Johnston M, Davis RW. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285(5429):901–6. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WH, Alami S, Luk E, Wu CH, Sen S, Mizuguchi G, Wei D, Wu C. Swc2 is a widely conserved H2AZ-binding module essential for ATP-dependent histone exchange. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12(12):1064–71. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Neupert W, Tzagoloff A. The metalloprotease encoded by ATP23 has a dual function in processing and assembly of subunit 6 of mitochondrial ATPase. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(2):617–26. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]