Abstract

α-Dystroglycan (DG) is a key component of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex. Aberrant glycosylation of the protein has been linked to various forms of congenital muscular dystrophy. Unusually α-DG has previously been demonstrated to be modified with both O-N-acetylgalactosamine and O-mannose initiated glycans. In the present study, Fc-tagged recombinant mouse α-DG was expressed and purified from human embryonic kidney 293T cells. α-DG glycopeptides were characterized by glycoproteomic strategies using both nano-liquid chromatography matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization and electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. A total of 14 different peptide sequences and 38 glycopeptides were identified which displayed heterogeneous O-glycosylation. These data provide new insights into the complex domain-specific O-glycosylation of α-DG.

Keywords: α-dystroglycan, glycoproteomics, mass spectrometry, O-GalNAc, O-mannose

Introduction

Muscular dystrophies, a group of diseases that cause severe muscle weakness and loss of skeletal muscle mass, are caused by mutations in genes that encode proteins of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC; Blake et al. 2002; Muntoni et al. 2002, 2004). The DGC is a multimeric, transmembrane protein complex that was first isolated from the sarcolemma of skeletal muscle. The central protein of the sarcolemma DGC is dystroglycan (DG), which binds to dystrophin and proteins within the basal lamina, establishing a critical link between the cytoplasm and the extracellular matrix (ECM; Ervasti and Campbell 1991, 1993; Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya et al. 1992). The DGC is not confined to skeletal muscle; DG is also expressed in the heart and smooth muscle, as well as many non-muscle tissues including the brain, peripheral nerve, epithelia, retina and kidney (Durbeej et al. 1995; Durbeej, Henry, Ferletta, et al. 1998). The protein composition of the DGC is tissue-dependent (Durbeej and Campbell 1999). The DGC in non-muscle tissue has been found to have roles in synaptogenesis, epithelial morphogenesis and early mouse development (Durbeej, Henry and Campbell 1998).

DG is encoded by a single gene: dystrophin-associated glycoprotein 1. The propeptide is cleaved by an unidentified protease into two subunits: α-DG and β-DG. α-DG resides on the outer surface of the cell membrane and binds tightly but non-covalently to the transmembrane subunit, β-DG (Ervasti and Campbell 1991; Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya et al. 1992). β-DG, in turn, connects intracellularly to dystrophin, which binds to the actin cytoskeleton (Ervasti and Campbell 1993). α-DG completes the link from the cytoskeleton to the ECM by binding to several extracellular ligands, including laminin, agrin, perlecan and neurexin (Gee et al. 1994; Sugiyama et al. 1994; Talts et al. 1999; Sugita et al. 2001). α-DG is made up of two globular domains separated by a central “mucin-like” domain (Talts et al. 1999). The N-terminal domain of α-DG appears to be commonly processed by furin-like activity, although evidence suggests that it remains associated with the rest of the DG protein in vivo (Barresi and Campbell 2006). Each of the ECM ligands possesses laminin-G-like domains that mediate their high-affinity, calcium-dependent binding to α-DG (Andac et al. 1999; Wizemann et al. 2003).

α-DG has extensive and heterogeneous glycosylation that is required for laminin-binding (Ervasti and Campbell 1993). Despite a predicted molecular weight of 72 kDa, the mature protein varies in apparent mass from 120 to 156 kDa, dependent on tissue source; 156 kDa in the rabbit skeletal muscle (Ervasti and Campbell 1993), 120 kDa in the rabbit and embryonic chick brain (Ervasti and Campbell 1993) and 140 kDa in the rabbit cardiac muscle (Ervasti et al. 1997). The extent of skeletal muscle α-DG glycosylation has also been found to increase during human development (Brown et al. 2004). Although it is evident that the glycan content of α-DG is functionally critical, the nature of α-DG glycosylation is still largely unknown. α-DG contains three potential N-linked glycosylation sites. Enzymatic removal of N-linked glycans alters the molecular weight of α-DG by ∼4 kDa (Ervasti and Campbell 1993). Furthermore, this treatment does not have any impact on its activity as an ECM receptor, indicating that the N-linked glycans are not required for ligand binding and therefore indicating that the carbohydrate content of α-DG that mediates binding is O-linked (Ervasti and Campbell 1993). The central domain of α-DG contains a large number of potential O-glycosylation sites (∼50 Ser/Thr residues in a region of around 170 amino acids) and has been assigned the “mucin-like” domain. α-DG has been found to carry a mixture of O-mannose and mucin-type O-GalNAc (N-acetylgalactosamine)-initiated structures (Chiba et al. 1997; Sasaki et al. 1998; Smalheiser et al. 1998).

In humans, recessive mutations in at least six genes result in the hypoglycosylation of α-DG leading to inherited muscular dystrophies (Hewitt 2009). Only the heterocomplex formed by the association of protein O-mannosyl-transferase 1 and 2 (POMT1 and POMT2) and protein O-linked-mannose β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 (POMGnT1) have been experimentally demonstrated to have glycosyltransferase activity, whereas fukutin, fukutin-related protein and LARGE-encoded proteins have homology to glycosyltransferases. In skeletal muscle, these genes are necessary for laminin-binding activity by α-DG, which is associated with immunoreactivity for two antibodies, IIH6 and VIA4 (Hewitt 2009).

Two recent studies have reported the site-specific O-glycosylation of α-DG from human and rabbit skeletal muscle (Nilsson et al. 2010; Stalnaker et al. 2010). The human study characterized 25 glycopeptides which corresponded to five tryptic peptides. Four of the peptides were heterogeneously glycosylated with both O-mannose and mucin-type O-GalNAc-initiated structures, whereas the fifth peptide, which contained the O-glycosylation sites at T367 and T369, was only modified by O-mannose glycans. The rabbit study characterized 91 glycopeptides and identified 9 sites with O-mannose structures and 14 sites with O-GalNAc-initiated structures. A third recent investigation expressed rabbit α-DG construct fragments in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells and found that one Thr residue in the mucin-like domain carries an unusual phosphorylated O-mannosyl glycan (Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. 2010). This O-mannosyl phosphorylation was shown to be a component of the post-translational modification of α-DG that is required for binding to laminin. The LARGE protein was shown to act downstream of the addition of this phosphorylation event.

In this paper, we describe the design of an Fc-tagged mouse α-DG construct, its expression and purification from HEK293T cells and its glycoproteomic O-glycan site-mapping. Characterization of mouse α-DG glycosylation is of particular interest as the mouse is utilized as a model organism in a number of animal models for the study of dystroglycanopathies.

Results

Expression and purification of recombinant mouse α-DG in HEK293T cells

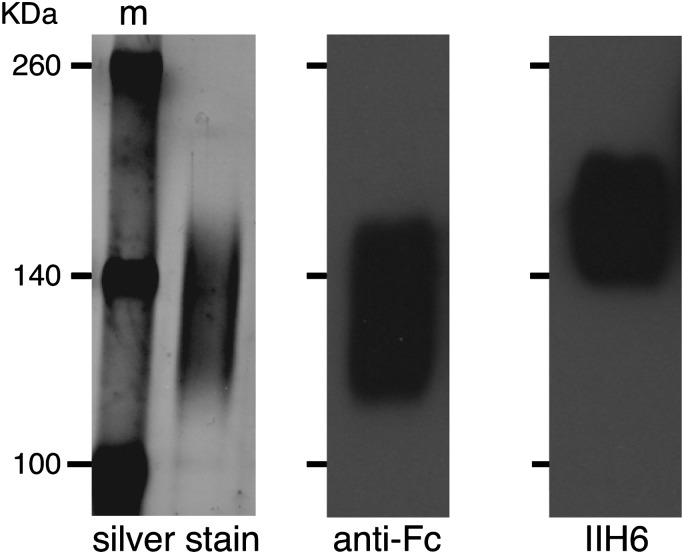

To obtain recombinant mouse α-DG, we used the mIgG2A-Fc2 vector system. We tested for secretion of the recombinant protein in both Chinese hamster ovary and HEK293 cells, as both systems had been used previously to generate recombinant, glycosylated DG (e.g. Kunz et al. 2001; Patnaik and Stanley 2005). The highest yields were generated from HEK293T cells. Therefore, for mass spectrometry analysis, we purified the α-DGFc fusion protein from the conditioned media of stably transfected HEK293T cells. Cells were grown in media containing ultra-low IgG serum to reduce the co-purification of immunoglobulins. The purified fusion protein, as visualized by silver staining, migrated as a heterogeneous smear of apparent mass 110–150 kDa that was positive with the Fc antibody (Figure 1). However, only the fraction of the fusion protein migrating at an apparent mass of 130-kDa was positive for the IIH6 antibody. Thus, not all of the secreted fusion protein contained this LARGE-dependent epitope. This is consistent with previous studies (Kunz et al. 2001; Patnaik and Stanley 2005) and might be a consequence of the high expression levels of the fusion protein.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of purified α-DGFc fusion protein. Aliquots of protein G-purified protein were separated by 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by silver staining or by immunoblotting with either anti-Fc antibody or IIH6 (to detect fully glycosylated α-DG). M, spectra molecular weight marker (Fermentas). The purified Fc fusion protein can be seen by silver staining to migrate as a heterogeneous smear of approximate apparent mass of 110–160 kDa. All of this material appeared positive with the Fc antibody. However, only a fraction of the fusion protein that migrated at an apparent mass of 130–170 kDa was positive for the IIH6 antibody.

Proteomic characterization of recombinant mouse α-DG by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry

An aliquot of purified recombinant mouse α-DG was reduced and carboxymethylated, digested with trypsin and subjected to offline nano-liquid chromatography (LC) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-time of flight (TOF)/TOF tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Major peaks from the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS) profiles were selected for collision-induced dissociation (CID) by MS/MS. Fragment ions detected in the MS/MS spectra were used to search the Swiss Prot database using the Mascot search engine for peptide sequences consistent with fragment ions observed. The Mascot search automatically identified 10 peptides from mouse α-DG. Detailed manual assessment of the data revealed additional peptides which had not been automatically assigned due to non-specific cleavages or peptides that contained a decomposed derivative of S-carboxymethylated methionine, dethiomethyl methionine, a modification that has been previously reported (Jones et al. 1994). An additional peptide 574GGLSAVDAFEIHVHK589 was observed in subsequent online nano-LC electrospray (Electrospray)-QSTAR MS experiments (Table I). Six peptides were also observed from the Fc-tag. A summary of the total mapped sequence of recombinant mouse α-DG is presented in Figure 2.

Table I.

Summary of α-DG peptides identified

| Identification process | Peptide sequence | Residues | Peak observed (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptides automatically identified by Mascot | GGEPNQRPELK | 481–491 | 1224.6 |

| VDAWVGTYFEVK | 497–508 | 1413.7 | |

| IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDK | 509–524 | 1861.9 | |

| IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDKLK | 509–526 | 2103.1 | |

| LREQQLVGEK | 531–540 | 1199.7 | |

| EQQLVGEK | 533–540 | 930.5 | |

| HEYFMHATDK | 564–573 | 1278.6 | |

| GGLSAVDAFEIHVHK | 574–589 | 790.92+ | |

| LAGDPAPVVNDIHK | 603–618 | 1445.8 | |

| IALVK | 618–622 | 543.4 | |

| LAFAFGDR | 624–631 | 896.5 | |

| Manual analysis of the data | SNSQLMYGLPDSSHVGK | 547–563 | 1771.9 (1819.8) |

| SQLMYGLPDSSHVGK | 549–563 | 1570.9 (1618.7) | |

| HEYFMHATDK | 564–573 | 1230.6 (1278.6) |

A total of 14 α-DG peptides were detected. Eleven α-DG peptides were identified automatically using Mascot. Three peptides containing dethiomethyl methionine (highlighted in bold) were identified by manual analysis of the data. Expected m/z values of the peptides containing these modified methionine residues are shown in parentheses. Peaks observed are [M + H]+, unless annotated with an alternative charge.

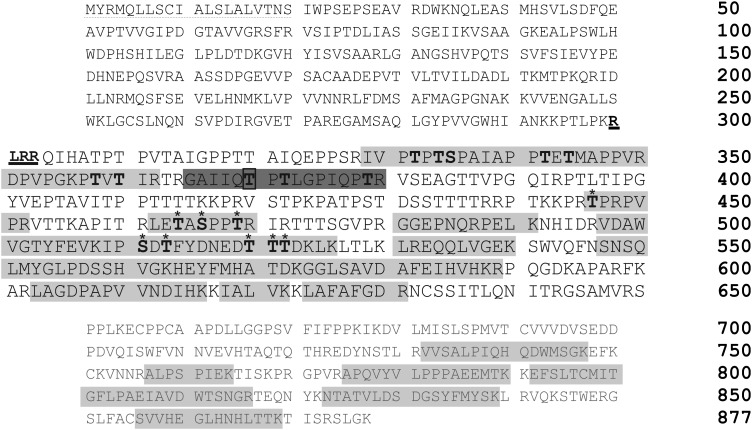

Fig. 2.

Mapped sequences of the recombinant mouse α-DG construct. The construct was expressed in HEK cells and then purified with protein G. Peptides highlighted in light grey correspond to those sequenced using offline nano-LC MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS and online nano-LC ES-QTOF MS/MS. Glycosylation sites of O-mannosylation are indicated with bold text and sites detected to be modified by GalNAc are indicated with bold text and an asterisk (*). The peptide highlighted in dark grey corresponds to the peptide containing the novel O-mannose structure (site of attachment is boxed in black). The region of the construct corresponding to the IL2 signal sequence is shown underlined with a dotted line, the Furin cleavage site in bold text with a solid underline and the Mouse IgG2a Fc domain in light grey text.

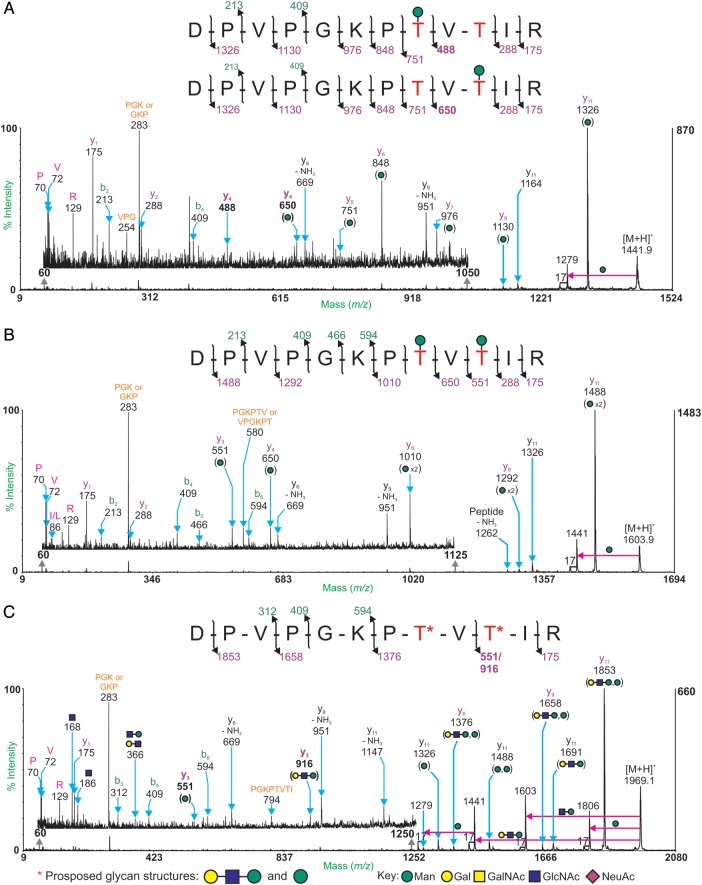

Characterization of O-mannosylated glycopeptides by MALDI-MS

Detailed assessment of the offline nano-LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS data revealed a number of peaks separated by increments corresponding to monosaccharide masses allowing identification as potential α-DG glycopeptides (Tables II–VII). For example, m/z 1603.9 is 162 Da (mass of a Hex residue) greater than m/z 1441.9 and further related signals at m/z 1807.0 and m/z 1969.1 correspond to m/z 1603.9 plus N-acetylhexosamine (HexNAc) and HexHexNAc, respectively. MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS analyses of these peaks confirmed the presence of glycosylation, via the loss of carbohydrate masses from the molecular ion peak, and revealed the peptide backbone sequence 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362 (with an expected Mr of 1278.7; Table II). This peptide contains two potential O-glycosylation sites. The annotated MALDI-TOF/TOF spectra of m/z 1441.9, 1603.9 and 1969.1 are shown in Figure 3.

Table II.

Glycans attached to Thr-358 and Thr-360 within the glycopeptide 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362

| Peak observed (m/z) | Mr | Peptide sequence | Glycopeptide minus peptide (Mr) | Glycan composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1441.9 | 1440.9 | 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362 | 162.2 | Hex |

| 1603.9 | 1602.9 | 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362 | 324.2 | Hex2 |

| 1807.0 | 1806.0 | 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362 | 527.3 | Hex2HexNAc |

| 1969.1 | 1968.1 | 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362 | 689.4 | Hex3HexNAc |

Four glycoforms of the peptide, 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362 (Mr = 1278.7), were identified using offline MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS. Potential O-glycosylation sites are underlined and peaks observed are [M + H]+. The Mr values correspond to non-protonated species.

Table III.

Glycans attached to Thr-332, Thr-334, Thr-335, Thr-342 and Thr-344 within the glycopeptide 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350

| Peak observed (m/z) | Mr | Peptide sequence | Glycopeptide minus peptide (Mr) | Glycan composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3371.8 | 3370.8 | 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 | 1176.6 | Hex6HexNAc |

| 3736.0 | 3735.0 | 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 | 1540.8 | Hex7HexNAc2 |

| 3784.9 | 3783.9 | 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 | 1589.7 | Hex7HexNAc2 |

| 4101.2 | 4100.2 | 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 | 1906.0 | Hex8HexNAc3 |

Four glycoforms of the peptides, 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 (Mr = 2242.2) and 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 (Mr = 2194.2), were identified using offline MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS. Potential O-glycosylation sites are underlined and bold methionine residues indicate dethiomethyl methionine residues. The Mr values correspond to non-protonated species.

Table IV.

Glycans attached to Thr-446 within the glycopeptide 446TPRPVPR452

| Peak observed (m/z) | Mr | Peptide sequence | Glycopeptide minus peptide (Mr) | Glycan composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1187.6 | 1186.6 | 446TPRPVPR452 | 365.1 | HexHexNAc |

| 1228.7 | 1227.7 | 446TPRPVPR452 | 406.2 | HexNAc2 |

Two glycoforms of the peptide, 446TPRPVPR452 (Mr = 821.5), were identified using offline MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS. Potential O-glycosylation sites are underlined. The Mr values correspond to non-protonated species.

Table V.

Glycans attached to Thr-370, Thr-372 and Thr-379 within the glycopeptide 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380

| Peak observed (m/z) | Mr | Peptide sequence | Glycopeptide minus peptide (Mr) | Glycan composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 912.52+ | 1823.0 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 161.1 | Hex |

| 993.62+ | 1985.2 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 323.2 | Hex2 |

| 1074.62+ | 2147.2 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 485.3 | Hex3 |

| 1176.72+ | 2351.4 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 689.5 | Hex3HexNAc |

| 825.53+ | 2554.2 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 892.3 | Hex3HexNAc2 |

| 1278.32+ | ||||

| 2555.2 | ||||

| 1359.32+ | 2716.6 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1054.7 | Hex4HexNAc2 |

| 974.33+ | ||||

| 1460.82+ | 2919.3 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1257.4 | Hex4HexNAc3 |

| 2920.3 | ||||

| 1504.82+ | 3007.6 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1346.0 | NeuAcHex4HexNAc2 |

| 1095.73+ | ||||

| 1541.92+ | 3081.8 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1419.9 | Hex5HexNAc3 |

| 1071.33+ | ||||

| 1606.42+ | 3210.8 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1548.9 | NeuAcHex4HexNAc3 |

| 1095.73+ | ||||

| 1643.52+ | 3284.4 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1622.5 | Hex5HexNAc4 |

| 3285.4 | ||||

| 1192.73+ | 3575.1 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 1913.6 | NeuAcHex5HexNAc4 |

| 1289.73+ | 3866.1 | 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 | 2204.2 | NeuAc2Hex5HexNAc4 |

Thirteen glycoforms of the peptide, 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380 (Mr = 1661.9), were identified in the bound fraction after WFA purification using both offline MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS and online ES-QSTAR MS/MS. Potential O-glycosylation sites are underlined and peaks observed are [M + H]+, unless annotated with an alternative charge. The Mr values correspond to non-protonated species.

Table VI.

Glycan compositions attached to Ser-511 and Thr-513, Thr-520, Thr-521 and Thr-522 within the peptide 509IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDKLK526

| Peak observed (m/z) | Mr | Peptide sequence | Glycopeptide minus peptide (Mr) | Glycan composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 958.83+ | 2873.4 | 509IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDKLK526 | 771.5 | HexHexNAc3 |

| 1055.93+ | 3164.7 | 509IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDKLK526 | 1062.8 | NeuAcHexHexNAc3 |

Two glycoforms of the peptide, 509IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDKLK526 (Mr = 2101.9), were identified in the bound fraction after WFA purification using online ES-QSTAR MS/MS. Potential O-glycosylation sites are underlined and peaks observed are [M + H]+, unless annotated with an alternative charge. The Mr values correspond to non-protonated species.

Table VII.

Glycan compositions attached to Ser-466 and Thr-464 and Thr-469 within the peptide, 462LETASPPTR470

| Purification fraction | Peak (m/z) | Mr | Potential peptide sequence | Glycopeptide minus peptide (Mr) | Glycan composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bound fraction | 770.42+ | 1538.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 568.3 | HexHexNAc2 |

| 790.92+ | 1579.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 609.3 | HexNAc3 | |

| 871.92+ | 1741.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 771.3 | HexHexNAc3 | |

| 953.02+ | 1904.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 933.5 | Hex2HexNAc3 | |

| 973.52+ | 1945.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 974.5 | HexHexNAc4 | |

| 703.43+ | 2107.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 1136.5 | Hex2HexNAc4 | |

| 1054.52+ | |||||

| 800.43+ | 2398.2 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 1427.7 | NeuAcHex2 HexNAc4 | |

| Wash fraction | 587.82+ | 1173.7 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 203.2 | HexNAc |

| 1174.7 | |||||

| 668.82+ | 1335.7 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 365.2 | HexHexNAc | |

| 1336.7 | |||||

| 689.42+ | 1376.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 406.3 | HexNAc2 | |

| 770.42+ | 1538.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 568.3 | HexHexNAc2 | |

| 790.92+ | 1579.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 609.3 | HexNAc3 | |

| 851.52+ | 1701.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 730.5 | Hex2HexNAc2 | |

| 871.92+ | 1741.8 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 771.3 | HexHexNAc3 | |

| 915.52+ | 1829.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 858.5 | NeuAcHex HexNAc2 | |

| 953.02+ | 1904.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 933.5 | Hex2HexNAc3 | |

| 1034.02+ | 2066.0 | 462LETASPPTR470 | 1095.5 | Hex3HexNAc3 |

Thirteen glycoforms of the peptide, 462LETASPPTR470 (Mr = 970.5), were identified in both the bound and wash fractions after WFA purification using online ES-QSTAR MS/MS. Potential O-glycosylation sites are underlined and peaks observed are [M + H]+, unless annotated with an alternative charge. The Mr values correspond to non-protonated species. Shaded rows indicate glycoforms that were detected in the wash fraction only.

Fig. 3.

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectra of the molecular ions at m/z 1441.9 (A), m/z 1603.9 (B) and m/z 1969.1 (C) from α-DGFc1. Peptide fragmentation provides strong evidence for the sequence 351DPVPGKTVTIR362. Intact y-ions are labeled in purple, intact b-ions are labeled in green and y- and b-ions with losses of monosaccharides, ammonia or water are labeled in black. Immonium ions are labeled in pink. Internal fragment ions are labeled in orange. The pink arrows show loss of the indicated glycan substituent. Ions diagnostic for glycosylation patterns are highlighted in bold.

The glycan attachment sites were determined by analysis of the peptide fragment ions. The MS/MS spectra suggest that both Thr-358 and Thr-360 can be glycosylated. This is shown by the presence of y4 ions at m/z 488 and 650 in the TOF/TOF spectrum of m/z 1441.9 and the absence of m/z 488 in the TOF/TOF spectrum of m/z 1969.1. Further confirmation is provided by the presence of the y3 ions at m/z 551 and 916 in the fragmentation spectrum of m/z 1969.1. The glycopeptides at m/z 1441.9 and 1603.9 carry a single hexose residue on the Thr residues. There is no evidence for a Hex–Hex sequence upon the fragmentation of m/z 1603.9. The pattern of monosaccharide losses from the molecular ion and subsequent y-ions in the fragment spectrum of m/z 1969.1 suggest that the glycans attached to the peptide backbone have the compositions Hex and Hex2HexNAc, which have been assigned as possible O-mannose glycans Man-Thr and Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Man-Thr.

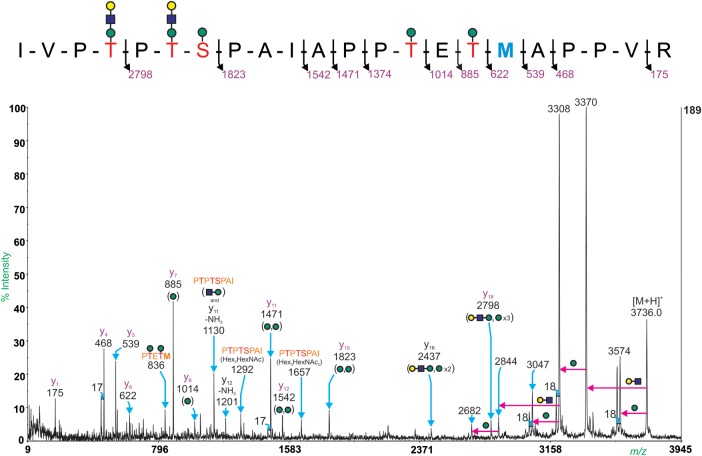

A second glycopeptide, which maps to 329IVPTPTSPAIA PPTETMAPPVR350 with a dethiomethyl methionine (Mr 2194.2), was identified (Table III). Peaks at m/z 3371.8, 3736.0 and 4101.2 have a mass equivalent to the peptide backbone plus glycan compositions of Hex6HexNAc, Hex7HexNAc2 and Hex8HexNAc3, respectively. The MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum of the ion at m/z 3736.0 can be seen in Figure 4. The peptide sequence contains five potential O-glycosylation sites, and the glycan compositions suggest that all five sites are at least glycosylated with a single hexose residue and several bear the extended trisaccharide structure (Hex-HexNAc-Hex). The size of the glycopeptides made it difficult to specify which Thr and Ser residues carried the disaccharide structure. Figure 4 shows the major structure of the molecular ion at m/z 3736.0. However, there are fragment ion peaks present that indicate heterogeneity.

Fig. 4.

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum of the glycopeptide at m/z 3736.0. Glycopeptide fragmentation provides strong evidence for the peptide sequence 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350. Y-ions are labeled in purple, no b-ions were observed. Immonium ions are labeled in pink. Internal fragment ions are labeled in orange. The pink arrows show loss of indicated glycan substituent. The major structure for the molecular ion at m/z 3736.0 is shown in the inset; however, the presence of the y16 ion at m/z 2437 provides evidence for the trisaccharide at the C-terminal Thr residues or the Ser residue. Methionine in bold blue indicates a dethiomethyl methionine.

Characterization of O-GalNAc glycopeptides by MALDI-MS

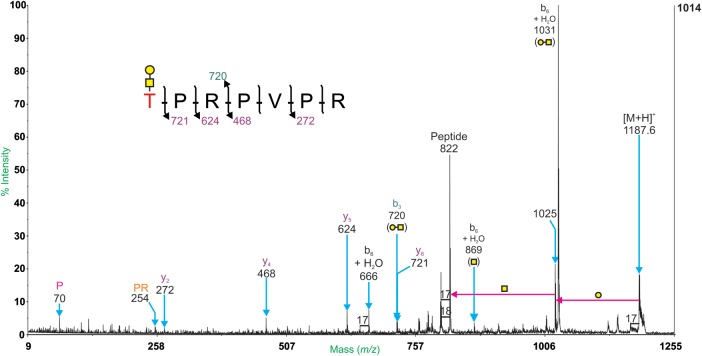

The peptide, 446TPRPVPR452, has a theoretical unglycosylated Mr of 821.5 Da. Related peaks at m/z 1187.6 and 1228.7 carry the glycan compositions HexHexNAc and HexNAc2, respectively (Table IV). The HexHexNAc moiety on the m/z 1187.6 molecular ion was assigned as a Core 1 mucin-type O-glycan (Galβ1,3GalNAc), based on the knowledge of the biosynthetic pathway and the loss of Hex followed by HexNAc in the MS/MS spectrum (Figure 5). The MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum for the molecular ion at m/z 1228.7 (data not shown) suggests the addition of a HexNAc2 moiety onto the N-terminal Thr residue. The HexNAc–HexNAc structure was putatively assigned as a core 3 mucin-type O-glycan (GlcNAcβ1,3GalNAc). It is important to note that the same composition could correspond to core 5, core 6 or core 7 structures; however, these are rare in mouse and human tissue (Wopereis et al. 2006).

Fig. 5.

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum of the glycopeptide at m/z 1187.6. Peptide fragmentation provides evidence for the sequence 446TPRPVPR452. Intact y-ions are labeled in purple, intact b-ions are labeled in green. Ions with additional water and losses of monosaccharides are labeled in black. Immonium ions are labeled in pink. Internal fragment ions are labeled in orange. The loss of Hex followed by HexNAc from the molecular ion (m/z 1025 and 822) suggests a mucin-type core 1 structure.

Characterization of Wisteria floribunda agglutinin lectin chromatography glycopeptides by MALDI-MS

Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. have demonstrated that a phosphorylated O-linked mannose structure is necessary for α-DG binding to laminin. Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. (2010) used the plant lectin, Wisteria floribunda agglutinin (WFA), to enrich glycopeptides carrying this glycan. WFA is a plant lectin that binds with high affinity to glycans containing terminal β-linked GalNAc residues (Torres et al. 1988). Peptides/glycopeptides from recombinant mouse α-DG were treated with 48% aqueous HF, conditions known to be specific for the cleavage of phosphodiester linkages. HF-treated peptides/glycopeptides were subsequently enriched using WFA lectin chromatography and the resulting bound and wash fractions were analyzed.

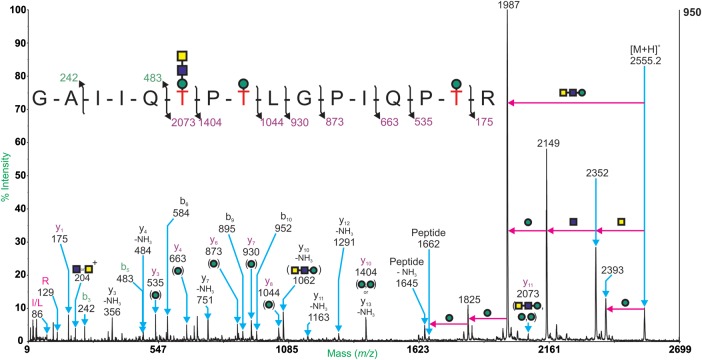

After WFA enrichment, offline nano-LC and MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the bound fraction revealed three peaks related by m/z 365 (HexHexNAc) increments. These are m/z 2555.2, 2920.3 and 3285.4. Evidence from MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectra confirmed that these peaks correspond to the glycopeptides 365GAIIQTPTLGPITR380 bearing the glycan HexNAc2Hex, which is fully consistent with the novel trisaccharide GalNAcβ1,3GlcNAc β1,4-mannitol (Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. 2010; Table V). Figure 6 shows the MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum of the glycopeptide at m/z 2555.2. The absence of HexNAc2Hex on the y3, y4, y6, y8, y7 and y10 ions suggests that Thr-370 of the construct is modified with the novel trisaccharide.

Fig. 6.

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum of the molecular ion at m/z 2555.2. Peptide fragmentation provides evidence for the sequence 365GAIIQTPTLGPITR380. A major structure for the molecular ion at m/z 2555.2 is shown in the inset. Y- and b-ions produced from fragmentation of this structure are labeled in purple and green, respectively. The pink arrows show the loss of the indicated glycan substituent. Immonium ions are labeled in pink.

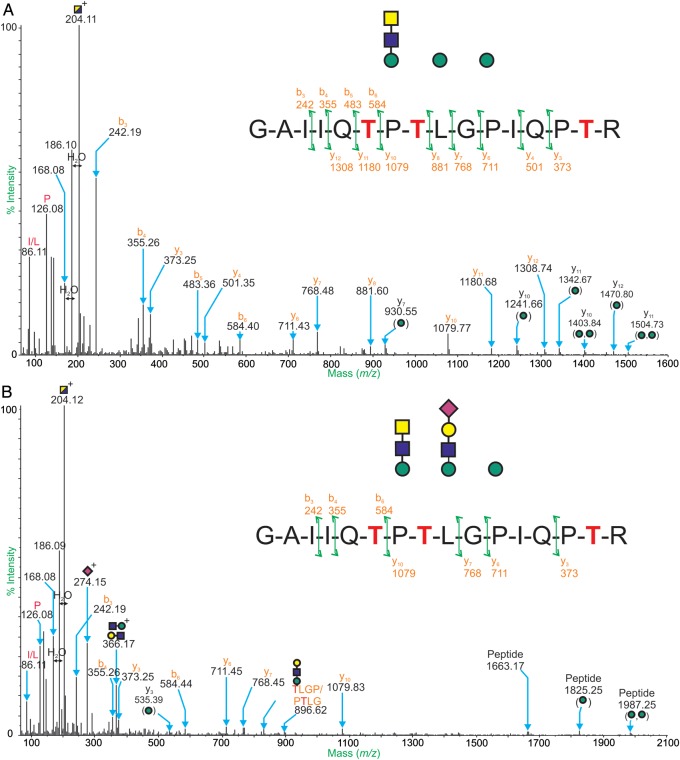

Characterization of WFA lectin chromatography glycopeptides by online nano-LC ES-QSTAR MS

An aliquot of bound glycopeptides was also analyzed by online nano-LC ES-QSTAR MS and MS/MS. Three glycopeptides were found in the ES-MS spectra. MS data between the ion retention times 40.0 and 41.6 min were summed and examined in detail. Doubly and triply charged ions separated by mass intervals consistent with monosaccharide masses were observed (Supplementary data, Figure S1 and Table S1). Subtracting the mass of the assigned glycan compositions from the calculated molecular weight of the ions gives a peptide backbone mass of 1661.9 Da. This mass can be assigned to the novel trisaccharide-bearing tryptic peptide seen in the MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS experiments; 365GAIIQTPTLGPITR380. Further evidence for this peptide backbone sequence was gained from CID-ES-MS/MS data. The ions at m/z 825.5 and 1071.3 were among those selected for data-dependent CID-ES-MS/MS, and the resulting spectra can be seen in Figure 7. The fragmentation of these molecular ions provides definite evidence for glycosylation through the presence of major low mass, singly charged signals corresponding to glycan fragments. Characteristic fragment ions are observed at m/z 204 (HexNAc+), m/z 366 (HexHexNAc+) and m/z 274 (NeuAc+). ES-MS/MS can also provide additional information about the peptide backbone sequence. The series of b-ions (b3, b4, b5 and b6) in both spectra provide evidence for the C-terminal sequence, GAIIQT, whereas the y-ions suggest the N-terminal sequence PTLGPIQPTR. y-ions such as those at m/z 1241.55 and 1403.84 (top panel) are evidence for the peptide plus carbohydrate compositions comprising a single hexose and two hexose residues, respectively (Table V).

Fig. 7.

CID-ES-MS/MS spectra of m/z 825.53+ (A) and m/z 1071.33+ (B) acquired during the WFA-enriched mouse α-DG online LC ES-MS/MS experiment. The peptide sequence assignments of 365GAIIQTPTLGPITR380 are provided in the schematic. Y-ions, b-ions and internal fragment ions are labeled in orange, immonium ions are labeled in pink and the peaks corresponding to carbohydrate fragments are annotated.

A second glycopeptide was identified in the online nano-LC ES-MS and MS/MS analysis of the bound α-DGFc. The glycopeptide eluted between 38.4 and 40.0 min. Two triply charged signals were observed (m/z 958.83+ and 1055.93+) consistent with the peptide backbone 509IPSDTFYDNEDTTTDKLK526 carrying HexHexNAc3 and NeuAcHexHexNAc3. This peptide contains five potential O-glycosylation sites. The ES-MS/MS data generated does not allow the assignment of the glycan components to specific sites but the peak at m/z 407 indicates the presence of the structure, HexNAc–HexNAc, which most likely corresponds to a core 3 O-glycan (GlcNAcα1,3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr). Binding to the WFA lectin column could be explained by the presence of the Tn antigen (GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr), unusual core structures or non-specific charged sialic acid interactions (Table VI).

Examination of the α-DG WFA bound fraction ES-MS data eluting between 27.1 and 28.5 min revealed the presence of a third glycopeptide. The molecular and fragment ion values were consistent with the peptide backbone sequence of 462LETASPPTR470. This peptide contains three potential O-glycosylation sites. The glycan compositions HexHexNAc2–NeuAcHex2HexNAc4 were assigned to mucin-type O-glycans with a large amount of GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr (Tn antigen) which could be the reason that the glycopeptides bound to the WFA column (Table VII).

An aliquot of the WFA lectin chromatography wash fraction was also subjected to online nano-LC ES-MS and MS/MS. The 462LETASPPTR470 glycopeptide eluted between 28.9 and 30.7 min. In the wash fraction, the glycan compositions contained more hexose HexNAc–Hex3HexNAc3 (Table VII). This increase in hexose may have decreased the amount of terminal GalNAc and therefore would explain why these glycopeptides did not bind to the lectin and were found in the wash fraction. A peak eluting in the wash fraction was observed at m/z 790.9+. This molecular ion mapped to a previously undetected α-DG peptide, 588GGLSAVDAFEIHVK603 (Table I).

Discussion

A total of 14 different peptide sequences and 38 glycopeptides from mouse α-DG were identified resulting in coverage of 49% of the sequence C-terminal to the furin-cleavage site (Figure 2). Peptides originating from the N-terminal region of the construct were not detected; this is presumed to be due to processing at the furin cleavage site and is consistent with the studies of Stalnaker et al. looking at endogenously purified protein from rabbit skeletal muscle. The 38 glycopeptides identified consisted of six different peptide backbones containing 19 potential glycosylation sites of which 11 were confirmed to be glycosylated; three of these glycopeptides were found to carry mucin-type, O-GalNAc initiated glycans and three glycopeptides contained nine Thr residues and one Ser residue carrying O-mannose initiated glycans. These glycopeptides displayed heterogeneity associated with both their glycan core structures and their glycan site occupancies. Only one site carrying the novel trisaccharide, previously shown to contain a phosphomannose residue (Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. 2010), was observed.

Between Ile-329 and Arg-380 (52 amino acid residues), 10 of the 11 Thr/Ser residues were found to carry O-mannose. The 11th residue, Thr-363, was not detected in our analyses. This was likely due to the short peptide backbone created by the tryptic digest, 363TR364, and the resulting low molecular weight and high hydrophilicity of the glycopeptide. No information about the peptide and associated glycosylation sites between Val-381 and Arg-445 of α-DG was acquired. These 65 amino acid residues make up a region containing 23 potential O-glycosylation site (Ser/Thr) residues and 11 Pro residues. One reason for not detecting the glycopeptides in this region could have been due to incomplete protease digestion restriction, caused by the densely packed glycosylation preventing trypsin from accessing the peptide backbone substrate. The resulting high molecular weight of the large peptide region plus the potential heterogeneity of glycosylation would lead to molecular ion amounts below the level of detection. A recent mass spectrometric analysis of the extracellular domain of Drosophila DG revealed an O-mannosylation-rich, trypsin-resistant region that was not amenable to MS analysis and was thought to correspond to the central mucin-like domain (Nakamura et al. 2010). We achieved a much higher degree of sequence coverage after the mucin-like domain, between the residues Thr-446 and Arg-631, where sequence coverage of 73.6% was achieved, and within this region, nine mucin-type O-glycosylation sites were detected.

A combination of complementary mass spectrometry instruments were utilized in this study. The ES-QSTAR MS/MS (CID-ES-MS/MS) spectrum is dominated by low mass carbohydrate fragment ions providing definite evidence for glycosylation. The y- and b-ions bear few or no glycan structures, allowing confident assignment of the peptide backbone. The carbohydrate fragment ions, however, can often suppress the signals from y- and b-ions. The MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS spectrum, on the other hand, is dominated by losses of the glycan components from the molecular ion. The order in which glycan components are lost provides information on the glycan sequence. In addition, y-ions that do not lose the glycan components allow the assignment of site-specific glycosylation. A second difference between MALDI and ES ionization highlighted in this study is the sensitivity to minor and sialylated components seen in ES-MS. No sialylated components were identified in the MALDI data due to loss of the sialic acid moiety during in-source decay and post-source decay. In contrast, during ES ionization, the sialic acid remains associated with the glycan allowing sialylated glycopeptides to be detected.

In their analysis of rabbit α-DG, Stalnaker et al. (2010) succeeded in characterizing 91 glycopeptides containing 21 O-glycosylation sites, 9 of which were O-mannosylated and 14 were O-GalNAcylated. In our study, we found one glycopeptide and two peptides that were not identified by Stalnaker et al. These were 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350, 547SNSQLMYGLPDSSHVGK563 and 588GGLSAVDAFEI HVK603. Detection of the large glycopeptide between Ile-329 and Arg-350 demonstrates the advantage of employing both MALDI and ES-MS instrumentation. This glycopeptide was only detected by MALDI-TOF MS. Detection of Ser-547 to Lys-563 was difficult due to unusual non-specific cleavage of the peptide backbone and was assigned only after intense manual analysis of the data. The absence of the rabbit peptide equivalent to 588GGLSAVDAFEIHVK603 (GGLSAVD AFEIHVHK) in the data set of Stalnaker et al. led them to hypothesize that a reason for this may be the presence of an additional phosphomannose moiety. However, in our recombinant mouse α-DG, this peptide was detected in an unglycosylated form [an observation that was also made during the analysis of human α-DG (Nilsson et al. 2010)], suggesting that the presence of an additional phosphomannose at this position is unlikely.

In the recombinant mouse α-DG, the peptide DPVPGKPTVTIR was found to carry O-mannose glycans. In contrast, in purified α-DG from rabbit skeletal muscle, these sites have been reported to bear mucin-type O-glycans (Stalnaker et al. 2010). In order for the authors to see this rabbit glycopeptide, glycosidases were used to reduce the heterogeneity of the glycopeptides. Interestingly, in another recent study, the only O-mannosylated sites identified in human α-DG were in the peptide, DPVPGKPTVTIR (Nilsson et al. 2010). Analysis of α-DG purified from human skeletal muscle tissue also revealed that O-glycosylation at the C terminus (after Thr-446) is mucin-type O-glycosylation, which is in agreement with data reported here. Stalnaker et al. do not agree with this observation; in rabbit skeletal muscle, O-mannose glycans were reported on the C-terminal peptides, LETASPPTR and TTTSGVPR. The discrepancies between human and rabbit skeletal muscle extracts suggest that there is species-specific variation in O-mannosylation patterns. Similarities between the glycosylation of recombinant mouse α-DG expressed in HEK cells and human α-DG demonstrates the validity of the system as a model for studying α-DG glycosylation.

Nilsson et al. used ES-MS/MS and, due to fragmentation limitations associated with this instrumentation, did not obtain information on glycan sequences or specific attachment sites. As a result, they speculated that an O-mannosylated Thr may carry a novel glycan structure with one or two Hex bound to the innermost O-mannose, leaving mucin-type O-glycosylation on the other Thr residues within the peptide (DPVPGKPTVTIR; Nilsson et al. 2010). In this report, using MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS, we were able to rule out potential novel structures and confirm that this peptide does carry the biosynthetically predicted O-mannosyl lactosamine structures. Nilsson et al. (2010) report limited structural variability and suggest a reason for this is that the O-mannosylation is specific and strictly regulated. In contrast, the data obtained during this study found a higher degree of heterogeneity in the O-mannosylated structures, e.g. the 13 forms of the glycopeptide, 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380, that were seen in the online LC ES-MS/MS experiment. Stalnaker et al. also report a similar level of heterogeneity of O-mannose structures on native rabbit α-DG. Nevertheless, compared with the potential heterogeneity displayed by mammalian mucin-type O-glycosylation [exemplified in a recent study by Ismail et al. (2011)], the array of reported O-mannose structures is relatively limited.

Analyses of rabbit skeletal muscle α-DG (Stalnaker et al. 2010) and Drosophila DG (Nakamura et al. 2010) revealed glycosylation sites that could be modified by either O-mannose or O-GalNAc. The finding that O-glycosylation sites could be modified with either O-mannose or O-GalNAc led to the suggestion that interplay exists between the two biosynthetic pathways. Stalnaker et al. observed both O-mannose and O-GalNAc glycans on Ser and Thr residues in the peptide LETASPPTR; in the analysis described here, this glycopeptide was identified only in the online nano-LC ES-MS and MS/MS experiment and therefore glycan compositions, not structures, could be assigned. The observation that a fraction of the glycopeptides bound to the WFA column and a fraction was collected in the wash may indicate that the presence of O-mannose initiated glycans in the wash fraction. Recent glycomic profiling of O-glycans from the stomach of mice deficient in core 2 β1,6-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases (C2GnT triple KO) revealed that when the core 2 mucin-type O-glycosylation pathway is disrupted stomach cells synthesize elongated O-mannose glycans containing up to three Fuc residues and three LacNAc repeats. The authors suggested that cells may amplify the addition of complex antennae to O-linked mannose in order to replace the diminished extended core 2 O-glycans (Ismail et al. 2011). This provides additional evidence for interplay between O-mannosylation and the O-GalNAcylation.

O-Mannosylation and O-GalNAcylation are two pathways that are theoretically competing for the same sites (Ser/Thr residues). However, enzymes for O-mannose attachment are localized to the ER and precede the O-GalNAc machinery that is localized in the cis-Golgi. Site-specificity of O-GalNAcylation appears to be a consequence of the large family of enzymes that catalyze the attached of α-GalNAc to Ser/Thr residues [UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases (pp-GalNAcTs)]. There are up to 20 different known isoforms of pp-GalNAcT. Many of these enzymes have clear specificities for the sites of attachment and are differentially expressed over tissue and time (Jensen et al. 2009; Perrine et al. 2009), permitting a complex and strict regulation. O-Mannosylation, in contrast, is synthesized by the action of two enzymes (POMT1 and POMT2) that form a single complex (Akasaka-Manya et al. 2006). Although an alternative splice form of POMT2 was found in the testis, it did not appear to be involved in O-mannosylation (Lommel et al. 2008). The importance of the O-mannose modification on α-DG and its restricted expression thus implies a different and much stricter regulation of O-mannosylation compared with O-GalNAcylation. Investigations into the mechanisms behind this strict regulation are needed.

In the study of human α-DG by Nilsson et al., the peptide LETASPPTR is reported to carry only mucin-type O-GalNAc initiated glycans. The authors suggest that O-mannosylation is a strictly regulated glycosylation that occurs at specific sites within α-DG to direct the synthesis of the large, unknown, phosphomannose-linked moiety (Nilsson et al. 2010). The distribution of the different O-glycosylation types on human α-DG and the localization of O-mannose glycans observed in recombinant mouse α-DG make this an attractive hypothesis. This would explain the finding of Combs and Ervasti (2005) who showed that when the O-mannose glycans were removed by glycosidases the binding of laminin was not affected.

Removal of the small O-mannose glycans after the synthesis of the large, functional moiety would not interfere with it binding to laminin. This hypothesis also provides an explanation for the involvement of the enzyme, POMGnT1 in the correct functioning of α-DG. The demonstration that addition of a large, unknown moiety via a phosphodiester linkage onto the mannose residue within GalNAcβ1,3GlcNAcβ1,4Man was necessary for correct α-DG functioning (Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. 2010) does not explain why mutations in POMGnT1 (an enzyme that catalyzes the addition of GlcNAc in a β1,2-linkage to O-linked mannose) also cause dystroglycanopathies in humans (Yoshida et al. 2001; Godfrey et al. 2007) and mice (Liu et al. 2006; Miyagoe-Suzuki et al. 2009). If a dense population of lactosamine-containing O-mannose glycans (NeuAcα2,3/Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1,2Man) play a role in the synthesis of the large, unknown, functional moiety, it is feasible that mutations in POMGnT1 would prevent proper α-DG function. It is worth noting that both in this paper and that of Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. a glycan is observed two amino acids C-terminal of the novel trisaccharide that has to have been biosythesized by the action of POMGnT1.

A recent, in vitro study by Manya et al. (2007) used a series of synthetic peptides derived from the mucin-like domain of α-DG and recombinant POMT1/2 enzymes to demonstrate that mammalian O-mannosylation prefers the amino acid sequence IXPT(P/X)TXPXXXXPT(T/X)XX. This proposed consensus sequence agrees with the glycopeptide, 329IVPTPTSPAIAPPTETMAPPVR350 (IXPT(P/X)TXPXXXXPT(T/X)XX), containing 5 of our 10 defined O-mannosylation sites. Three further O-mannosylated sites, in the peptide 365GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR380, are in a similar sequence, only deviating from the proposed consensus sequence twice; IXQT(P/X)TXGPXXPT(T/X)XX. Nevertheless, the remaining two O-mannosylation sites, present in the peptide 351DPVPGKPTVTIR362, did not agree with the consensus sequence. Additional contradicting evidence was provided by a blast search undertaken by Manya et al. (2007) that revealed α-DG as the only protein containing this consensus sequence. In their glycoproteomic analysis of rabbit α-DG, Stalnaker et al. (2010) also concluded that O-mannosylation of particular residues is not regulated solely by a local consensus sequence. The large amounts of O-mannose initiated glycans seen in the mouse brain (Parry et al. 2007), and the recent glycomics investigation revealing large amounts of O-mannosylation in the gastrointestinal tract of a mouse model with the disrupted core 2 O-glycosylation pathway (Ismail et al. 2011) suggests that O-mannosylation is a lot more prevalent than originally thought. This has additionally been shown in a recent paper by Stalnaker et al. (2011) who utilized glycomic methodologies to characterize O-glycosylation in the mouse brain released from proteins of three different knockout mouse models associated with O-mannosylation.

A subsequent study by Breloy et al. (2008) used recombinant fragments of human α-DG expressed in epithelial cell lines and argued that O-mannosylation was a doubly controlled process involving an upstream peptide region and residues flanking the modified Ser/Thr residue. The upstream peptide region (equivalent to Glu-369 to Ile-409 in the construct studied here) was reported to be necessary and sufficient to induce O-mannosylation. This peptide was not upstream of any of the 10 O-mannosylation sites identified. The authors also suggest that flanking basic amino acid residues increases O-mannosylation of Ser and Thr residues. However, 9 of 10 O-mannosylated Ser/Thr residues reported here do not have flanking basic residues, and the alignment of the 10 O-mannosylation sites provided no obvious local consensus sequence for attachment.

Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. (2010) showed that treating purified α-DG from mouse skeletal muscle with cold hydrofluoric acid (which cleaves phosphodiester linkages) resulted in a reduction in mass (from 150 to 70 kDa) and loss of the IIH6 epitope and laminin-binding activity. MS and NMR analysis of a peptide fragment from the mucin-like domain of rabbit α-DG produced in a HEK293 expression system, identified the phosphorylated O-mannosyl trisaccharide with the structure GalNAcβ1,3GlcNAcβ1,4(C6-phosphate)Manα-Ser/Thr. This novel O-linked mannose structure represents the first vertebrate non-glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein modified by a phosphodiester linkage (Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. 2010). After treatment with hydrofluoric acid and purification by WFA lectin chromatography, a glycopeptide carrying the novel trisaccharide at position Thr-379 was observed (374GAIIQTPTLGPIQPTR389). Data presented in this study demonstrated a greater heterogeneity of glycan structures on Thr-370, Thr-372 and Thr-379, with larger sialylated glycan structures. Our data are fully consistent with the presence of a phosphorylated O-mannosyl trisaccharide with the structure GalNAcβ1,3GlcNAcβ1,4(C6-phosphate)Man. However, it should be noted that the phosphorylated O-mannosyl trisaccharide was not directly observed. This is most likely due to the smaller amount of starting material utilized in comparison with Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. This is the first report of the phosphorylated O-mannose moiety on analysis of a full-length α-DG, as Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. used a fragment corresponding to the mucin-like domain of the protein, and the recent glycoproteomic analyses of α-DG purified from rabbit skeletal muscle and human skeletal muscle did not observe this peptide and corresponding trisaccharide. We note that both mass spectrometric analyses of this novel glycan have utilized recombinant α-DG expressed in HEK cell expression systems, and therefore, it is possible that this modification reflects the use of this cell system and might be different from what happens in muscle tissue.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of recombinant mouse α-DG in HEK293T cells (α-DGFc)

The cDNA fragment corresponding to amino acid residues 29–651 of mouse α-DG was amplified by polymerase chain reaction from IMAGE clone 3,496,914 and cloned into pFUSE-mIgG2A-Fc2 (Invivogen, Paisley, UK). HEK293T adherent cells were grown in the Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 25 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL of penicillin and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin and transfected with the recombinant plasmid. Stable cell lines expressing secreted α-DGFc fusion protein were selected by the addition of 400 µg/mL of zeocin and maintained by growing in 100 µg/mL of zeocin. For recombinant protein production, the α-DGFc-expressing HEK293T cells were transferred to the DMEM containing 10% (v/v) ultra-low IgG fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL, Paisley, UK). The conditioned medium was incubated with protein G-agarose (Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK) for 4 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed extensively with 1.5 M glycine, 3 M NaCl, pH 9.0, and the bound α-DGFc protein was eluted with 0.2 M glycine–HCl, pH 2.8, and neutralized by addition of 1 M Tris–HCl, pH 9.0. Protein recovery and purity were assessed by silver staining of PAGE gels and western blotting using antibodies against the Fc domain (horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse Fc; Pierce, Loughborough, UK) or the IIH6 epitope (Upstate, Abingdon, UK).

Reduction and carboxymethylation of recombinant mouse α-DG

The sample was dissolved in degassed Tris (0.6 M, pH 8.5), incubated with 1.5 mg of dithiothreitol at 37°C for 1 h and carboxymethylated with 20 mg of iodoacetic acid at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. The reaction was terminated by transferring the protein into a dialysis cassette and dialyzing against regular changes of Ambic buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5) at 4°C for 48 h.

Tryptic digestion of recombinant mouse α-DG

About 20 µg of lyophilized sequencing grade modified trypsin was reconstituted with 20 µL of acidic trypsin buffer (1 µg/µL) and a 200-µL working solution (100 ng/mL) was created by the addition of Ambic buffer (50 mM, pH 8.4). A protease:protein ratio of 1:100 to 1:20 (w/w) was added to the sample and incubated at 37°C for 14–16 h. A drop of 5% (v/v) acetic acid terminated the reaction and the products were purified by reverse-phase chromatography on a Classic C18 cartridge using the propan-1-ol/5% (v/v) acetic acid system.

Hydrofluoric acid hydrolysis

Glycans and glycopeptides were lyophilized in Lo-bind® Eppendorfs and resuspended in 50 µL of a 48% (v/v) HF (Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) solution. The tube was sealed and the reaction was carried out at 4°C for 20 h, before being dried under gentle stream nitrogen.

WFA lectin chromatography

Lyophilized glycopeptides were resuspended in 0.5 mL of degassed WFA buffer (10 mM phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4). After the 2 mL of lectin column was pre-equilibrated with 30 mL of degassed WFA buffer, the sample was loaded and washed with ∼5 column volumes of WFA buffer. The bound glycopeptides were then eluted with 3–4 volumes of elution buffer (0.1 M lactose in WFA buffer). The wash and eluted bound fractions were collected in 15-mL falcon tubes. The amount of material coming off the lectin column was monitored using a UV detector to follow the chromatography at 214 or 280 nm. The column was regenerated with NaCl (1.4 M) between samples.

Offline LC- MALDI-TOF and TOF/TOF of (glyco)peptides

Tryptic digests were dissolved in 40 µL 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and separated by nano-LC using an Ultimate 3000 (LC Packings, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) fitted with a Pepmap analytical C18 nanocapillary. After loading in 2% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN) containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA, the column was eluted with a gradient from 0 to 60% (v/v) ACN over 36 min at a flow rate of 0.3 µL/min. Sample elutions were spotted directly onto a steel MALDI target plate using a Probot (LC Packings, Dionex) with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix at a concentration of 3.3 mg/mL. Peptides were subjected to MALDI-MS profiling, complemented with MS/MS sequencing of the 10 most abundant ions in each sample, on an Applied Biosystems 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer. For peptide mass fingerprint data, peak picking was conducted using GPS Explorer software version 3.6 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A signal-to-noise threshold of 10 was used, sequazyme peptide mass standards were used as external standards for calibration and no contaminant ions were excluded. For MS/MS experiments, peak list generation and database searching were conducted using GPS Explorer software version 3.6 (Applied Biosystems) with the default parameters. Both MS and MS/MS data were used to search 283,454 entries in release 54.2 of the SwissProt database with version 2.2 of the Mascot database search algorithm (www.matrixscience.com) with the following parameters: peptide masses were fixed as monoisotopic, partial oxidation of methionine residues was considered, partial carboxymethylation of cysteine residues was considered, the mass tolerance was set at 75 ppm for precursor ions and 0.1 Da for fragment ions and tryptic digests were assumed to have no more than one missed cleavage. Peptide matches from both MS and MS/MS data were used to generate probability-based Mowse protein scores. Scores of >55 were considered significant (P < 0.05).

Online LC-ES MS and MS/MS with a QSTAR mass spectrometer

Tryptic digests, resuspended in 0.1% (v/v) TFA, were analyzed by nano-LC-ES-MS/MS using a reverse-phase nano-high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system [LC Packings, Dionex (UK) Ltd, Camberley] connected to a quadrupole TOF mass spectrometer (API Q-STAR® Pulsar i, Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Toronto, Canada). Online peptide separation was achieved by a binary nano-HPLC gradient generated by an UltiMate pump fitted with a Famos autosampler and a Switchos microcolumn switching module [Dionex (UK) Ltd, Camberley], utilizing a pre-microcolumn C18 cartridge and an analytical C18 nanocapillary (75 mm inside diameter × 15 cm, PepMap, Dionex (UK) Ltd, Camberley). The digest was first loaded onto the precolumn and eluted with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water. The eluate was then transferred onto the analytical nanocapillary HPLC column and eluted using a gradient of solvent A [0.05% (v/v) formic acid in a 95.5% (v/v) water/ACN mixture] and solvent B [0.04% (v/v) formic acid in a 95.5% (v/v) ACN/water mixture]. The instrument was pre-calibrated using 10–100 fmol/µL of [Glu1]-fibrinopeptide B human/5% (v/v) acetic acid (1:3, v/v). In the MS/MS mode, the collision gas utilized was nitrogen and the pressure was maintained at 5.3 × 10−5 Torr.

ES-QSTAR MS and MS/MS data processing and interpretation

Data acquisition was performed using Analyst QS (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) software with an automatic information-dependent-acquisition function.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this article is available online at http://glycob.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Research Council (BBSRC) (SF19107, B19088 and BBF0083091) to A.D. and S.M.H, a BBSRC Ph.D. Studentship to R.H. and a BBSRC Research Development Fellowship to J.E.H. D.M. is supported by an MRC studentship, and R.J.P. by a Wellcome Trust (082915/B/07/Z).

Abbreviations

ACN, acetonitril; DG, dystroglycan; DGC, dystrophin–glycoprotein complex; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; ECM, extracellular matrix; ES, electrospray; Gal, galactose; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; HEK, human embryonic kidney; Hex, hexose; HexNAc, N-acetylhexosamine; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; LacNAc, Galβ1-4GlcNAc; LC, liquid chromatography; Man, mannose; MALDI, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization; MS, mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; NeuAc, N-acetylneuraminic acid; POMGnT1, protein O-linked-mannose β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1; POMT, protein O-mannosyl-transferase; pp-GalNAcT, polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; TOF, time of flight.

Supplementary Material

References

- Akasaka-Manya K, Manya H, Nakajima A, Kawakita M, Endo T. Physical and functional association of human protein O-mannosyltransferases 1 and 2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19339–19345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601091200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M601091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andac Z, Sasaki T, Mann K, Brancaccio A, Deutzmann R, Timpl R. Analysis of heparin, alpha-dystroglycan and sulfatide binding to the G domain of the laminin alpha1 chain by site-directed mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:253–264. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2606. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barresi R, Campbell KP. Dystroglycan: From biosynthesis to pathogenesis of human disease. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:199–207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02814. doi:10.1242/jcs.02814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE, Davies KE. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:291–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breloy I, Schwientek T, Gries B, Razawi H, Macht M, Albers C, Hanisch FG. Initiation of mammalian O-mannosylation in vivo is independent of a consensus sequence and controlled by peptide regions within and upstream of the α-dystroglycan mucin domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18832–18840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802834200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M802834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Torelli S, Brockington M, Yuva Y, Jimenez C, Feng L, Anderson L, Ugo I, Kroger S, Bushby K, et al. Abnormalities in α-dystroglycan expression in MDC1C and LGMD2I muscular dystrophies. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63160-4. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba A, Matsumura K, Yamada H, Inazu T, Shimizu T, Kusunoki S, Kanazawa I, Kobata A, Endo T. Structures of sialylated O-linked oligosaccharides of bovine peripheral nerve α-dystroglycan. The role of a novel O-mannosyl-type oligosaccharide in the binding of α-dystroglycan with laminin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2156–2162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2156. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.4.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs AC, Ervasti JM. Enhanced laminin binding by α-dystroglycan after enzymatic deglycosylation. Biochem J. 2005;390:303–309. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050375. doi:10.1042/BJ20050375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M, Campbell KP. Biochemical characterization of the epithelial dystroglycan complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26609–26616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26609. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.37.26609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M, Henry MD, Campbell KP. Dystroglycan in development and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:594–601. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80034-3. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M, Henry MD, Ferletta M, Campbell KP, Ekblom P. Distribution of dystroglycan in normal adult mouse tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:449–457. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600404. doi:10.1177/002215549804600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M, Larsson E, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Roberds SL, Campbell KP, Ekblom P. Non-muscle alpha-dystroglycan is involved in epithelial development. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:79–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.79. doi:10.1083/jcb.130.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti JM, Burwell AL, Geissler AL. Tissue-specific heterogeneity in α-dystroglycan sialoglycosylation. Skeletal muscle α-dystroglycan is a latent receptor for Vicia villosa agglutinin b4 masked by sialic acid modification. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22315–22321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22315. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.35.22315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. Membrane organization of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Cell. 1991;66:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90035-w. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90035-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:809–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.809. doi:10.1083/jcb.122.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee SH, Montanaro F, Lindenbaum MH, Carbonetto S. Dystroglycan-α, a dystrophin-associated glycoprotein, is a functional agrin receptor. Cell. 1994;77:675–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90052-3. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey C, Clement E, Mein R, Brockington M, Smith J, Talim B, Straub V, Robb S, Quinlivan R, Feng L, et al. Refining genotype phenotype correlations in muscular dystrophies with defective glycosylation of dystroglycan. Brain. 2007;130:2725–2735. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm212. doi:10.1093/brain/awm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt JE. Abnormal glycosylation of dystroglycan in human genetic disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Ervasti JM, Leveille CJ, Slaughter CA, Sernett SW, Campbell KP. Primary structure of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature. 1992;355:696–702. doi: 10.1038/355696a0. doi:10.1038/355696a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail MN, Stone EL, Panico M, Lee SH, Luu Y, Ramirez K, Ho SB, Fukuda M, Marth JD, Haslam SM, et al. High-sensitivity O-glycomic analysis of mice deficient in core 2 β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology. 2011;21:82–98. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq134. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwq134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PH, Kolarich D, Packer NH. Mucin-type O-glycosylation – putting the pieces together. FEBS J. 2009;277:81–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07429.x. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MD, Merewether LA, Clogston CL, Lu HS. Peptide map analysis of recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor: Elimination of methionine modification and nonspecific cleavages. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:135–146. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1017. doi:10.1006/abio.1994.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S, Sevilla N, McGavern DB, Campbell KP, Oldstone MB. Molecular analysis of the interaction of LCMV with its cellular receptor α-dystroglycan. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:301–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104103. doi:10.1083/jcb.200104103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Ball SL, Yang Y, Mei P, Zhang L, Shi H, Kaminski HJ, Lemmon VP, Hu H. A genetic model for muscle–eye–brain disease in mice lacking protein O-mannose 1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (POMGnT1) Mech Dev. 2006;123:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommel M, Willer T, Strahl S. POMT2, a key enzyme in Walker–Warburg syndrome: Somatic sPOMT2, but not testis-specific tPOMT2, is crucial for mannosyltransferase activity in vivo. Glycobiology. 2008;18:615–625. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn042. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manya H, Suzuki T, Akasaka-Manya K, Ishida HK, Mizuno M, Suzuki Y, Inazu T, Dohmae N, Endo T. Regulation of mammalian protein O-mannosylation: Preferential amino acid sequence for O-mannose modification. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20200–20206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702369200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Masubuchi N, Miyamoto K, Wada MR, Yuasa S, Saito F, Matsumura K, Kanesaki H, Kudo A, Manya H, et al. Reduced proliferative activity of primary POMGnT1-null myoblasts in vitro. Mech Dev. 2009;126:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.12.001. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni F, Brockington M, Blake DJ, Torelli S, Brown SC. Defective glycosylation in muscular dystrophy. Lancet. 2002;360:1419–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11397-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni F, Brockington M, Torelli S, Brown SC. Defective glycosylation in congenital muscular dystrophies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:205–209. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200404000-00020. doi:10.1097/00019052-200404000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Stalnaker SH, Lyalin D, Lavrova O, Wells L, Panin VM. Drosophila dystroglycan is a target of O-mannosyltransferase activity of two protein O-mannosyltransferases, Rotated Abdomen and Twisted. Glycobiology. 2010;20:381–394. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp189. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwp189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J, Larson G, Grahn A. Characterization of site-specific O-glycan structures within the mucin-like domain of α-dystroglycan from human skeletal muscle. Glycobiology. 2010;20:1160–1169. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq082. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwq082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry S, Ledger V, Tissot B, Haslam SM, Scott J, Morris HR, Dell A. Integrated mass spectrometric strategy for characterizing the glycans from glycosphingolipids and glycoproteins: Direct identification of sialyl Lex in mice. Glycobiology. 2007;17:646–654. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm024. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik SK, Stanley P. Mouse large can modify complex N- and mucin O-glycans on α-dystroglycan to induce laminin binding. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20851–20859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500069200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M500069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine CL, Ganguli A, Wu P, Bertozzi CR, Fritz TA, Raman J, Tabak LA, Gerken TA. Glycopeptide-preferring polypeptide GalNAc transferase 10 (ppGalNAc T10), involved in mucin-type O-glycosylation, has a unique GalNAc-O-Ser/Thr-binding site in its catalytic domain not found in ppGalNAc T1 or T2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20387–20397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017236. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.017236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Yamada H, Matsumura K, Shimizu T, Kobata A, Endo T. Detection of O-mannosyl glycans in rabbit skeletal muscle α-dystroglycan. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1425:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00114-7. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(98)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalheiser NR, Haslam SM, Sutton-Smith M, Morris HR, Dell A. Structural analysis of sequences O-linked to mannose reveals a novel Lewis X structure in cranin (dystroglycan) purified from sheep brain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23698–23703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23698. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.37.23698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker SH, Hashmi S, Lim JM, Aoki K, Porterfield M, Gutierrez-Sanchez G, Wheeler J, Ervasti JM, Bergmann C, Tiemeyer M, et al. Site mapping and characterization of O-glycan structures on α-dystroglycan isolated from rabbit skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24882–24891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126474. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.126474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker SH, Kazuhiro A, Lim JM, Porterfield M, Liu M, Satz JS, Buskirk S, Xiong Y, Zhang P, Campbell KP, et al. Glycomic analyses of mouse models of congenital muscular dystrophy. J Biol Chem. 2011;288:201180–201190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita S, Saito F, Tang J, Satz J, Campbell K, Sudhof TC. A stoichiometric complex of neurexins and dystroglycan in brain. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105003. doi:10.1083/jcb.200105003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama J, Bowen DC, Hall ZW. Dystroglycan binds nerve and muscle agrin. Neuron. 1994;13:103–115. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90462-6. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talts JF, Andac Z, Gohring W, Brancaccio A, Timpl R. Binding of the G domains of laminin α1 and α2 chains and perlecan to heparin, sulfatides, α-dystroglycan and several extracellular matrix proteins. EMBO J. 1999;18:863–870. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.863. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.4.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres BV, McCrumb DK, Smith DF. Glycolipid-lectin interactions: Reactivity of lectins from Helix pomatia, Wisteria floribunda, and Dolichos biflorus with glycolipids containing N-acetylgalactosamine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;262:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90161-0. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(88)90161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wizemann H, Garbe JH, Friedrich MV, Timpl R, Sasaki T, Hohenester E. Distinct requirements for heparin and α-dystroglycan binding revealed by structure-based mutagenesis of the laminin α2 LG4–LG5 domain pair. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:635–642. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00848-9. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00848-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wopereis S, Lefeber DJ, Morava E, Wevers RA. Mechanisms in protein O-glycan biosynthesis and clinical and molecular aspects of protein O-glycan biosynthesis defects: A review. Clin Chem. 2006;52:574–600. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.063040. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2005.063040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Kobayashi K, Manya H, Taniguchi K, Kano H, Mizuno M, Inazu T, Mitsuhashi H, Takahashi S, Takeuchi M, et al. Muscular dystrophy and neuronal migration disorder caused by mutations in a glycosyltransferase, POMGnT1. Dev Cell. 2001;1:717–724. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00070-3. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida-Moriguchi T, Yu L, Stalnaker SH, Davis S, Kunz S, Madson M, Oldstone MB, Schachter H, Wells L, Campbell KP. O-Mannosyl phosphorylation of alpha-dystroglycan is required for laminin binding. Science. 2010;327:88–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1180512. doi:10.1126/science.1180512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.