Abstract

The measurement of mitochondrial biogenesis is important in the determination of aging and disease processes and the assessment of countermeasurements to them. We argue that the frequently used assessments of cell signaling, mitochondrial protein mRNA, mitochondrial protein expression or enzyme activity, and mitochondrial density are not measurements that can lead to conclusions about mitochondrial biogenesis. Instead, we propose that only measurements of mitochondrial synthesis are indicative of biogenesis. Clarification of this issue will hopefully result in further differentiation of the processes important for morphological and functional changes of mitochondria.

Keywords: content, protein synthesis, chronic disease

proper functioning of the mitochondria reticulum contributes to health, and reciprocally, mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to a variety of chronic conditions, such as obesity (8), insulin resistance (18), heart disease (1), and aging (24). Mitochondria are 1) a primary site of generation of reactive oxygen species and the resultant positive and negative outcomes of their production, 2) central to the decision process of whether a cell will survive or undergo programmed cell death, and 3) the primary determinant of cellular energetic state that dictates metabolic outcomes. Therefore, the assessment of mitochondrial structure and function has become important in the study of human health and disease.

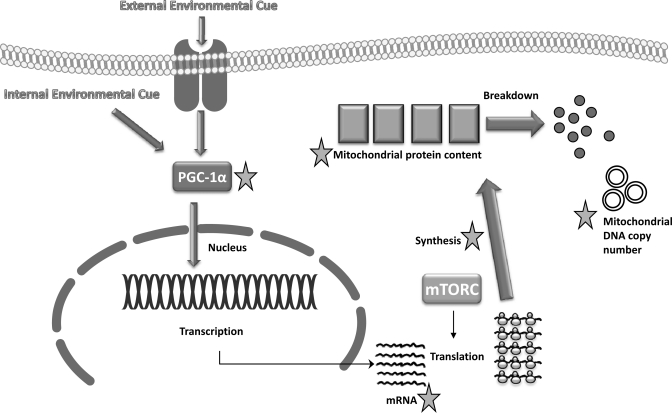

The concept that the mitochondrial reticulum continuously turns over by regulated processes of fission and fusion has become increasingly obvious in recent years (9). The mitochondrial reticulum is made of proteins and protein complexes that control aerobic energy production and exists as subpopulations in tissues such as skeletal muscle to support different energetic processes (e.g., membrane transport vs. contractile activity). The making of new mitochondrial reticular components (Fig. 1) requires the coordination of two genomes for the complete compliment of mitochondrial proteins, the vast majority of which are encoded by nuclear genes, with a much smaller number encoded by mitochondrial DNA. The mitochondrial reticulum is not made de novo but rather recruits new proteins to the organelle with subsequent division by fission (22). Mitochondrial dynamics vary by tissue where the reticulum undergoes a series of fission and fusion events and moves according to energetic need throughout the cell (12). Over time, mitochondrial proteins accumulate damage from reactive oxygen species, enzymatic and nonenzymatic modifications, and other environmental insults. To repair damaged proteins, the cell undergoes turnover of component proteins, autophagy (or mitophagy) of the organelle, or, under extreme conditions, programmed cell death. Protein turnover encompasses both protein synthesis and breakdown, both of which are important in the repair process.

Fig. 1.

Common sites of “mitochondrial biogenesis” assessment. Stars represent common sites of assessment. PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α; mTORC, mammalian target of rapamycin complex.

The purpose of this perspective is to stimulate discussion on the appropriate use of the term “mitochondrial biogenesis” and to provide our interpretation of what the appropriate assessment of mitochondrial biogenesis is. Biogenesis by definition is “the making of new,” and this shapes our interpretation of what the appropriate measurement of mitochondrial biogenesis is. Figure 1 highlights key regulatory steps in the determination of mitochondrial content and why assessment of some of these steps may lead to erroneous conclusions about biogenesis.

Assessment Based on Signaling

The process of mitochondrial biogenesis requires the coordination of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, which has resulted in a focused investigation into peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) (23), the so-called “master regulator” of mitochondrial biogenesis. Studies too numerous to detail have concluded that mitochondrial biogenesis is under transcriptional regulation (representative reviews include Refs. 4, 7, 11, 13, and 26), and many have used increases in PGC-1α mRNA or protein, nuclear translocation of PGC-1α, and increases in downstream signaling (e.g., nuclear respiratory factor-1 and mitochondrial transcription factor A) as experimental evidence of increased mitochondrial biogenesis (for example, see Refs. 3, 15, and 28). Although the increase in transcription that PGC-1α regulates is important to the making of new mitochondrial proteins, by itself it is not sufficient as a measurement of mitochondrial biogenesis.

To clarify why PGC-1α is not sufficient by itself in determining mitochondrial biogenesis, the example of cellular energetic stress will be used. During energetic stress, posttranscriptional mechanisms become increasingly important in the determination of whether a protein will be synthesized. In the basal state, protein synthesis is the largest consumer of ATP (21), with translation being 10 times more energetically costly than transcription (27). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is the energy sensor of the cell, and, independent of other cellular signals, it activates PGC-1α presumably to increase the potential for aerobic energy production when energetically challenged. However, activation of AMPK also simultaneously downregulates translation through inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and its downstream effectors (6). Therefore, when considering an energetic stress, although it is presumed that activation of AMPK, and subsequently PGC-1α, increases mitochondrial biogenesis (10), this presumption ignores the fact that AMPK is simultaneously downregulating translation initiation through mTOR. Under these conditions, if one measured signaling only through PGC-1α content or activation, it would be concluded that mitochondrial biogenesis increased. But if one measured both PGC-1α content and activation and mTOR signaling, it would be hard to predict or determine what the actual outcome of mitochondrial protein was. Because of examples such as energetic stress, it is not surprising that proteomic analyses of mitochondria have demonstrated that mRNA content does not necessarily correspond with protein abundance (16). Therefore, signaling through PGC-1α by itself does not necessarily indicate mitochondrial biogenesis.

Assessment Based on Content

Many have taken the approach of measuring mitochondrial content for the determination of mitochondrial biogenesis. The determination of mitochondrial content can be done several different ways, including, but not limited to, mitochondrial protein mRNA, mitochondrial enzyme content or activity (e.g., citrate synthase), mitochondrial DNA content, or mitochondrial density, as determined by immunohistochemistry. These measurements of content are informative when determining an overall change in the quantity of mitochondria; however, they do not determine biogenesis.

As mentioned, mitochondrial biogenesis is the making of new mitochondria and is reflective of synthesis. Content, on the other hand, is reflective of the processes of synthesis and degredation. To provide an example of why this is important, consider a condition in which mitochondrial protein synthesis doubles. The doubling of mitochondrial protein synthesis would be considered a positive outcome. However, if that doubling of synthesis was matched by a doubling of breakdown (an equally beneficial effect in the context of getting rid of damaged protein), there would be no change in content. Conversely, a state in which mitochondrial protein synthesis is maintained or decreased could result in an increase in mitochondrial protein content if breakdown is decreased to a greater extent. In this case, although the content is maintained or increased, the overall decrease in turnover that led to it is not necessarily a positive outcome. It is well known that chronic diseases and aging and their countermeasurements have dynamic effects on both synthesis and breakdown. Therefore, a change in content cannot be assumed to be due solely to changes in synthesis and is therefore not indicative of biogenesis. Furthermore, measurements of content obscure potentially important changes in turnover that contribute to the slowing or progression of disease processes.

Why Does This Matter?

To better understand the importance of identifying what mitochondrial biogenesis is, aging research serves as an effective example. Many research groups are interested in identifying interventions to extend healthspan in older individuals. Importantly, it has been proposed that mitochondrial deterioration contributes to the aging process (24), whereas mitochondrial biogenesis slows the aging process and extends healthspan (13). It has been demonstrated repeatedly that caloric restriction (CR) without malnutrition extends lifespan and healthspan. It has been proposed that some of the beneficial effects of CR are mediated through an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis. Some have published studies concluding that CR increases mitochondrial biogenesis (2, 17), whereas others strongly challenge this assertion (5), thus creating ambiguity in the field. Importantly though, in the aforementioned articles signaling of mitochondrial biogenesis via transcription factors or content of mitochondrial DNA, mRNA, and protein is measured. Although they are informative about signaling and content, in none of the studies was biogenesis actually measured, thus confusing the issue.

From these aforementioned studies, it is reasonable to believe that CR increases the cell signals for mitochondrial biogenesis, but because of the energetic demands of protein synthesis, those signals may be thwarted through AMPK inhibition of mTOR. Alternatively, it is equally reasonable to suspect that CR increases protein breakdown, and thus any increase in mitochondrial biogenesis would have to have been to such an extent that there was a net increase in protein content. However, without a determination of actual biogenesis, neither of these interpretations can actually be confirmed.

As indicated throughout this perspective, we believe the measurement of mitochondrial synthesis is the correct means to assess mitochondrial biogenesis. We have taken the approach of measuring mitochondrial protein synthesis with stable isotopic tracers (14, 19, 20), although other strategies such as mitochondrial membrane phospholipid or mitochondrial DNA synthesis are theoretically possible. One strength of measuring protein synthesis as a measurement of new mitochondria is that it circumvents complications associated with mitochondrial membrane remodeling (i.e., fission and fusion). When long-term changes in mitochondrial protein synthesis in CR mice were examined at three different ages, it was determined that mitochondrial biogenesis is maintained in CR mice over the lifespan (14). The picture that is emerging from studies on lower eukaryotes is that there may be alternative mechanisms by which mitochondrial protein synthesis is maintained, although global protein synthesis is decreased by mTOR inhibition (29).

In our minds, although we have appropriately assessed mitochondrial biogenesis, there remains a need to identify suitable assessments of breakdown and autophagy (mitophagy) since they are equally important opposing processes to biogenesis. The process of fission precedes mitophagy, and both can have profound effects on mitochondrial function. By these mechanisms, areas of dysfunctional mitochondria and mutated mtDNA can be isolated and broken down (25). The influence that breakdown processes have on mitochondrial function serves to illustrate that mitochondrial biogenesis cannot be considered in isolation when considering mitochondrial function. Although both biogenesis and breakdown are likely to have beneficial effects, the process or mechanism by which they do so is different. Importantly, as argued above, in the context of aging or chronic disease, the measurement of biogenesis provides insight into mitochondrial adaptations that cannot be gathered from signaling or content alone since increased turnover, even in the absence of changes in content, represents positive outcomes regarding protein stability. A critical need is to develop appropriate in vivo measurements of mitophagy as the opposing process to mitochondrial biogenesis.

Conclusions

The measurement of mitochondrial biogenesis is important in the determination of aging and disease processes and the assessment of countermeasurements to them. We argue that, although they are informative for other purposes, the frequently used assessments of signaling or content are not appropriate for drawing conclusions about mitochondrial biogenesis. Instead, we propose that only measurements of mitochondrial synthesis, such as protein, membrane, or DNA, are indicative of biogenesis. Clarification of this issue will hopefully result in further identification of the processes important for morphological and functional changes of mitochondria.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant no. 1-K01-AG-031829-01A1 and Grant no. DARPA N66001-10-c-2134 (to K. L. Hamilton) from the University of Colorado Denver.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.F.M. and K.L.H. did the conception and design of the research; B.F.M. and K.L.H. performed the experiments; B.F.M. analyzed the data; B.F.M. and K.L.H. interpreted the results of the experiments; B.F.M. and K.L.H. prepared the figures; B.F.M. and K.L.H. drafted the manuscript; B.F.M. and K.L.H. edited and revised the manuscript; B.F.M. and K.L.H. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Matthew Hickey for feedback.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chicco AJ, Sparagna GC. Role of cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C33–C44, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, Hulver MH, Ukropcova B, Deutsch WA, Smith SR, Ravussin E. Calorie restriction increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in healthy humans. PLoS Med 4: e76, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis JM, Murphy EA, Carmichael MD, Davis B. Quercetin increases brain and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and exercise tolerance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1071–R1077, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1α, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr 93: 884S–890S, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hancock CR, Han DH, Higashida K, Kim SH, Holloszy JO. Does calorie restriction induce mitochondrial biogenesis? A reevaluation. FASEB J 25: 785–791, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 115: 577–590, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem 47: 69–84, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim JY, Hickner RC, Cortright RL, Dohm GL, Houmard JA. Lipid oxidation is reduced in obese human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E1039–E1044, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirkwood SP, Munn EA, Brooks GA. Mitochondrial reticulum in limb skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 251: C395–C402, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leick L, Fentz J, Biensø RS, Knudsen JG, Jeppesen J, Kiens B, Wojtaszewski JF, Pilegaard H. PGC-1α is required for AICAR-induced expression of GLUT4 and mitochondrial proteins in mouse skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299: E456–E465, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lelliott CJ, Vidal-Puig A. PGC-1beta: a co-activator that sets the tone for both basal and stress-stimulated mitochondrial activity. Adv Exp Med Biol 646: 133–139, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu X, Weaver D, Shirihai O, Hajnóczky G. Mitochondrial ‘kiss-and-run’: interplay between mitochondrial motility and fusion-fission dynamics. EMBO J 28: 3074–3089, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. López-Lluch G, Irusta PM, Navas P, de Cabo R. Mitochondrial biogenesis and healthy aging. Exp Gerontol 43: 813–819, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller BF, Robinson MM, Bruss MD, Hellerstein M, Hamilton KL. A comprehensive assessment of mitochondrial protein synthesis and cellular proliferation with age and caloric restriction. Aging Cell 11: 150–161, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miura S, Kawanaka K, Kai Y, Tamura M, Goto M, Shiuchi T, Minokoshi Y, Ezaki O. An increase in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) mRNA in response to exercise is mediated by beta-adrenergic receptor activation. Endocrinology 148: 3441–3448, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mootha VK, Bunkenborg J, Olsen JV, Hjerrild M, Wisniewski JR, Stahl E, Bolouri MS, Ray HN, Sihag S, Kamal M, Patterson N, Lander ES, Mann M. Integrated analysis of protein composition, tissue diversity, and gene regulation in mouse mitochondria. Cell 115: 629–640, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nisoli E, Tonello C, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Falcone S, Valerio A, Cantoni O, Clementi E, Moncada S, Carruba MO. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science 310: 314–317, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 350: 664–671, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robinson MM, Bell C, Peelor FF, 3rd, Miller BF. β-Adrenergic receptor blockade blunts postexercise skeletal muscle mitochondrial protein synthesis rates in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R327–R334, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robinson MM, Richards JC, Hickey MS, Moore DR, Phillips SM, Bell C, Miller BF. Acute β-adrenergic stimulation does not alter mitochondrial protein synthesis or markers of mitochondrial biogenesis in adult men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R25–R33, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rolfe DF, Brown GC. Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiol Rev 77: 731–758, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. Mitochondrial-nuclear communications. Annu Rev Biochem 76: 701–722, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steinberg G, Kemp B. AMPK in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev 89: 1025–1078, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, Bohlooly-Y M, Gidlöf S, Oldfors A, Wibom R, Törnell J, Jacobs HT, Larsson NG. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 429: 417–423, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Twig G, Shirihai OS. The interplay between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 1939–1951, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res 79: 208–217, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wagner A. Energy constraints on the evolution of gene expression. Mol Biol Evol 22: 1365–1374, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu Z, Huang X, Feng Y, Handschin C, Feng Y, Gullicksen PS, Bare O, Labow M, Spiegelman B, Stevenson SC. Transducer of regulated CREB-binding proteins (TORCs) induce PGC-1alpha transcription and mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 14379–14384, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zid BM, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Vargas MA, Kolipinski MC, Lu TA, Benzer S, Kapahi P. 4E-BP extends lifespan upon dietary restriction by enhancing mitochondrial activity in Drosophila. Cell 139: 149–160, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]