Abstract

Natural selection often produces convergent changes in unrelated lineages, but the degree to which such adaptations occur via predictable genetic paths is unknown. If only a limited subset of possible mutations is fixed in independent lineages, then it is clear that constraint in the production or function of molecular variants is an important determinant of adaptation. We demonstrate remarkably constrained convergence during the evolution of resistance to the lethal poison, tetrodotoxin, in six snake species representing three distinct lineages from around the globe. Resistance-conferring amino acid substitutions in a voltage-gated sodium channel, Nav1.4, are clustered in only two regions of the protein, and a majority of the replacements are confined to the same three positions. The observed changes represent only a small fraction of the experimentally validated mutations known to increase Nav1.4 resistance to tetrodotoxin. These results suggest that constraints resulting from functional tradeoffs between ion channel function and toxin resistance led to predictable patterns of evolutionary convergence at the molecular level. Our data are consistent with theoretical predictions and recent microcosm work that suggest a predictable path is followed during an adaptive walk along a mutational landscape, and that natural selection may be frequently constrained to produce similar genetic outcomes even when operating on independent lineages.

Keywords: coevolution, molecular evolution, pleiotropy

The degree to which adaptive evolution is predictable at the molecular level remains controversial. On the one hand, convergent phenotypes are expected to arise from unique and unpredictable genetic changes because of the distinct evolutionary history and genetic makeup of independent species and the stochastic nature of mutation and drift. On the other hand, functional constraints (1, 2), patterns of pleiotropy (3–6), and developmental biases (7–10) might filter the available spectrum of mutations to a limited but tolerable cast (3, 5, 6). If adaptive evolution is constrained by the biophysical properties of interacting molecules (1, 2, 11) or limited by developmental and structural constraints (7–10), then adaptive substitutions might be concentrated at a relatively few genetic hotspots and fix in a repeated and predictable fashion (5, 6, 12).

We evaluated the predictability of adaptation at the molecular level by investigating the genetic basis of resistance to tetrodotoxin (TTX) in lineages of predatory snakes that consume toxic amphibians. TTX is a lethal defensive compound found in the skin secretions of a wide variety of amphibians (13, 14). Roughly 500 times deadlier than cyanide, TTX is one of the most potent natural toxins ever discovered (15). TTX operates by binding to the outer pore of voltage-gated sodium channels in nerves and muscles, blocking the movement of sodium ions (Na+) across cell membranes and halting action potentials that control nerve impulses (16). Despite the lethality of this neurotoxin, diverse lineages of snakes have evolved the ability to exploit TTX-bearing prey (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1) and are exceptional as the only known vertebrate predators of tetrodotoxic organisms (17). In western North America, populations of Pacific newts (Taricha) harbor extreme levels of TTX (18) but are preyed on by multiple garter snake species (Thamnophis): Thamnophis sirtalis preys on Taricha granulosa (17, 19); Thamnophis couchii preys on Taricha torosa (20) and Taricha sierrae (21); and Thamnophis atratus consumes Taricha granulosa (22). In Central and South America, the only known predator of highly poisonous Atelopus toads (23, 24) is the Neotropical ground snake, Liophis epinephelus (25, 26). In southern Japan, the tetrodotoxic newt Cynops ensicauda (27) is taken by Pryer's keelback, Amphiesma pryeri (28, 29), and in East Asia the TTX-bearing tree frog Polypedates cf leucomystax (30) is preyed on by the tiger keelback, Rhabdophis tigrinus (31). Natural selection on these independent lineages of predators is expected to have led to convergent resistance to TTX at the organismal level but not necessarily via the same physiological or genetic mechanisms.

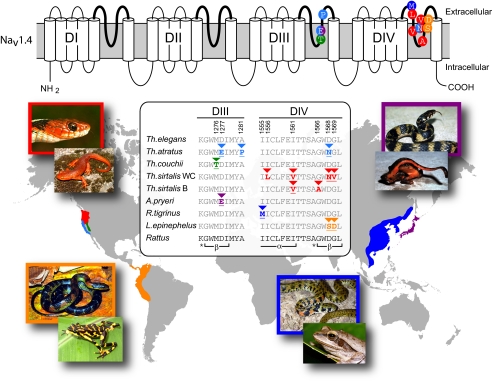

Fig. 1.

Parallel arms races between lethal, TTX-bearing amphibians and resistant snakes are expected to have evolved independently across the globe through convergent amino acid substitutions. In parts of North America, Th. sirtalis (red), Th. atratus (light blue), and Th. couchii (green) prey on Taricha newts (19–22); in parts of Central and South America L. epinephelus (orange) consumes Atelopus toads (25, 26); Japanese A. pryeri (purple) eats the newt C. ensicauda (28, 29); and Asian R. tigrinus (dark blue) preys on the tree frog P. leucomystax (31). (Upper) 2D structure of the α-subunit of skeletal muscle sodium channel (Nav1.4) showing the four domains (DI–DIV), their six transmembrane segments, and the linkers that connect segments. Four polypeptide chains link the final two transmembrane segments of each domain to form the ion-conducting outer pore (P-loops) of the sodium channel (bold). Although a number of residues in each P-loop are known to be important in TTX binding to the pore, all the adaptive variation in snakes is clustered in DIII and DIV (circles on P-loops: T, threonine; E, glutamic acid; P, proline; M, methionine; L, leucine; V, valine; A, alanine; N, asparagine; S, serine; D, aspartic acid). (Lower) Detailed alignment of the DIII and DIV P-loop sequences in TTX-resistant snakes highlighting the adaptive replacements (triangles above residues). Identical or functionally equivalent replacements occur at most of the same residues (underlined) in Nav1.4 of tetrodotoxic pufferfish. Note that separate alleles have proliferated in western populations of Th. sirtalis (B, Benton County; WC, Willow Creek), but we assume they share I1561V through common descent. Rat sequence (NM013178) and nonresistant garter snake (Th. elegans) sequence are given for comparison; positions follow Nav1.4 coding sequence from Th. sirtalis AY851746. Structures of the pore labeled below rat sequence (*, selectivity filter; α, α-helix; β, β-strand). Colors are coded by species as above.

The genetic basis of TTX resistance is known for only one group of predators, the garter snakes (Thamnophis). Structural changes in the skeletal muscle sodium channel (Nav1.4) modify the molecular environment of the channel pore and dramatically alter TTX-binding affinity to the protein (32). Functional allelic variation in Nav1.4 correlates tightly with whole-animal resistance to TTX and suggests that changes in this single gene are largely responsible for within- and among-population differences in resistance (32–34). Because TTX binds so selectively to the pore of sodium channels, we predict that biophysical constraints associated with channel function have led to a limited set of convergent molecular adaptations to the challenge of TTX-bearing prey worldwide.

We examined sequence variation in the four domains of Nav1.4 (DI–DIV) that encode the outer pore of the channel (P-loops) and whose residues interact with TTX (35–38) for six species of snakes known to prey on TTX-bearing amphibians, their sister groups, and additional taxa (74 species; n = 121 individuals) to provide a robust phylogenetic perspective (Methods). We scored organismal TTX resistance for nearly half these species (29 species; n = 424) using a performance bioassay (Methods). We then compared the observed substitutions in snakes with the spectrum of mutations in mammalian constructs that are known to increase the resistance of sodium channels to TTX to determine whether adaptive evolution in snakes has capitalized on these options randomly or used a restricted subset of these options (Methods).

Results and Discussion

Genetic Basis of TTX Resistance in Snakes.

Amino acid sequences of the pore-forming structures (pore α-helix, selectivity filter, β-strand) are highly conserved across colubroid snakes and are nearly identical to mammalian sequences. In the P-loops of TTX-sensitive reptiles we found only eight replacements, all at sites not implicated in TTX binding. However, in the six species that consume TTX-bearing prey, we found 13 derived substitutions, all at positions that influence TTX affinity (Fig. 1 and Movie S1). Nine of these substitutions replace amino acids in the β-strand, whose side chains face the pore and interact directly with TTX (Fig. 2 and Movie S1) (35–38). Mapping these changes and the TTX-resistance data onto the colubroid phylogeny (Fig. S1) clearly demonstrates that high sensitivity to TTX is the ancestral condition and that TTX resistance has evolved independently at least six times in snakes. Functionally similar (and sometimes identical) P-loop replacements occur in Nav1.4 of TTX-bearing pufferfish (39–41) (the only other TTX-resistant vertebrate whose sodium channels have been characterized) in all but two of the sites modified in TTX-resistant snakes (Fig. 1).

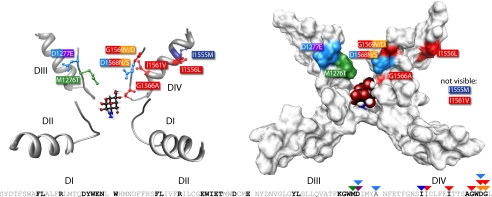

Fig. 2.

Structural model of the Nav1.4 outer pore (following ref. 35) with TTX docking in the pore (also see Movie S1). Adaptive replacements in DIII and DIV P-loops of snakes (colors follow Fig. 1) change the electrostatic environment and geometry of the outer pore, weakening TTX binding to the pore (see text for details). (Upper Left) Ball-and-stick model. (Upper Right) Space-filling model. (Lower) Amino acid sequence of the four P-loops (Rat NM013178) highlighting residues known to affect TTX binding to the pore (bold; see text) and positions where adaptive variation in snakes is clustered (triangles above residues).

Garter snakes (Thamnophis) that prey on Pacific newts (Taricha) exhibit multiple replacements in DIII and DIV; one in Th. couchii (42), three in Th. atratus (34), and up to four in Th. sirtalis (32). The single M1276T replacement in Th. couchii (positions follow Nav1.4 CDS from Th. sirtalis AY851746) produces a 15-fold decrease in TTX binding to the channel (40); the I1561V substitution in Th. sirtalis halves TTX-binding affinity (32); and the shared D1568N replacement in Th. atratus and Th. sirtalis produces a 30- to 40-fold decrease in TTX binding to the channel (43, 44).

The Neotropical ground snake, L. epinephelus, the only known predator of the highly toxic harlequin toads (Atelopus) (25, 26), displays two flanking mutations in the DIV β-strand. The first mutation, a D1568S replacement, occurs at the same position where a D→N replacement is seen in highly resistant Th. atratus and Th. sirtalis. This site plays a critical role in TTX binding because a hydrogen bond forms between TTX and D1568 (37, 44). Changes that neutralize the charged D1568, such as S, dramatically reduce TTX affinity to the outer pore (43, 45). The second P-loop change, G1569D, should alter the docking orientation of TTX into the outer pore (37, 44) and may weaken the affinity of TTX to the neighboring D1568 residue further (41). In L. epinephelus, the G1569D substitution involves dramatically different amino acids and likely changes the conformation of the external mouth of the outer pore and possibly pore volume. L. epinephelus also is one of the few predators of deadly dart-poison frogs (25), some of which possess batrachotoxin (BTX) and pumiliotoxin (PTX-B) (46). Both toxins interfere with Na+ channel inactivation, causing the channels to remain persistently open (16, 47, 48). However, these toxins do not bind to the outer pore but instead to the inner pore (BTX) (48–50) or to other transmembrane helices (PTX-B) (47, 51). Thus, although overall Na+ channel structure in L. epinephelus likely is influenced by multiple prey toxins, we are confident that the P-loop replacements we discuss have been shaped by selection from TTX, because the outer pore is the target of TTX, and these functional mutations are at sites critical to TTX binding but uninvolved in BTX or PTX-B binding (47–51).

Japanese A. pryeri consume the tetrodotoxic newt C. ensicauda (28, 29) and have a single D1277E substitution in the DIII β-strand. This replacement involves biochemically similar amino acids, and mutations at this position generally lead to only minor changes in TTX binding (44, 45). Nevertheless, substitutions involving similar amino acids at positions thought to have little involvement with TTX can still produce significant reductions in TTX-binding affinity (e.g., I1561V) (32).

The Asian keelback R. tigrinus preys on the TTX-bearing tree frog P. leucomystax (31) and displays an I1555M change in the DIV α-helix. This substitution occurs at a TTX-sensing residue (37), and the loss of a rigid alphatic side chain and gain of a larger functional group is expected to alter the orientation of the α-helix and thus the geometry of the outer pore, thereby indirectly weakening TTX-binding affinity to the pore (38).

Constraints on Convergent Evolution.

Phenotypic convergence, or the evolution of similarity in divergent lineages, is pervasive in biological systems and is thought to demonstrate the primacy of natural selection because the repeated occurrence of similarity by chance seems unlikely. However, the basis of convergence, particularly at the molecular level, can be strongly biased through biophysical or biochemical constraints on proteins (1, 2, 11) and by commonalities in the genetic architecture underlying the phenotype (i.e., genetic channeling; see ref. 52). These constraints may restrict available routes through the adaptive landscape and bias trait evolution (53, 54). Thus, both natural selection and evolutionary constraints likely are involved in convergent evolution (8, 9, 12, 55).

A number of residues distributed throughout the four P-loops contribute to TTX-binding affinity (n = 35; Methods), and mutations at any of these sites are candidates for adaptation of TTX resistance. For example, TTX-bearing pufferfish possess adaptive changes in the P-loops of all four domains (39–41). However, the replacements fixed during the evolution of resistance in snakes are limited to only two domains (DIII and DIV) and a fraction (26%) of the possible sites. In fact, seven of the 13 substitutions are confined to the same three positions, and two of these substitutions involve the same amino acid (we assume coincident I1561V in Th. sirtalis represents a single event). We observe a departure from the null expectation of a Poisson distribution of mutations (random events) whether we liberally consider all P-loop sites available for substitution (χ2 = 338.45, P < 0.0001) or conservatively consider only those sites experimentally verified to reduce TTX binding to the pore significantly (χ2 = 54.31, P = 0.015).

Why has the evolution of TTX resistance centered on such a predictable subset of relevant mutations? Many of the amino acids that form the outer pore to create the optimal environment for the selective permeation of Na+ ions also interact strongly with TTX (36), so changes that reduce the affinity of TTX to the outer pore are likely to have pleiotropic effects on the molecular sieving of the sodium channel. Data from ex vivo expression of sodium channels altered through site-directed mutagenesis of specific residues (Methods) indicate that amino acid substitutions in the P-loops that decrease TTX-binding affinity also tend to reduce Na+ permeability or Na+ selectivity (Fig. 3 and Table S1). This tradeoff between TTX resistance and sodium channel performance is a consequence of the neutralization of negative charges that line the outer pore and changes in pore volume or aperture (45, 56). Thus, a number P-loop replacements with dramatic effects on TTX resistance—perhaps the majority—will have a low probability of fixation because of their high functional cost. We suggest this antagonistic pleiotropy within Nav1.4 has contributed to the constrained convergence across lineages of snakes at the molecular level; the pool of mutations that can reduce TTX affinity and at the same time preserve critical sodium channel functions is limited. Notably, there are remarkable patterns of molecular convergence among pufferfish (39–41) and between pufferfish and snakes, but pufferfish have been able to exploit a wider diversity of mutations (in all four P-loops) than those observed in snakes. These differences may result from taxon-specific tradeoffs, constraints, or selective demands. Our results suggest that evolutionary constraints based on the functional consequences of amino acid replacements limit the spectrum of genetic variation available for adaptive evolution and shape the route to convergence. The extent to which the traits behind such evolutionary convergence are constrained remains to be seen, but it may be that natural selection often is tightly bound, leading diverse evolutionary lineages along repeatable genetic and phenotypic responses.

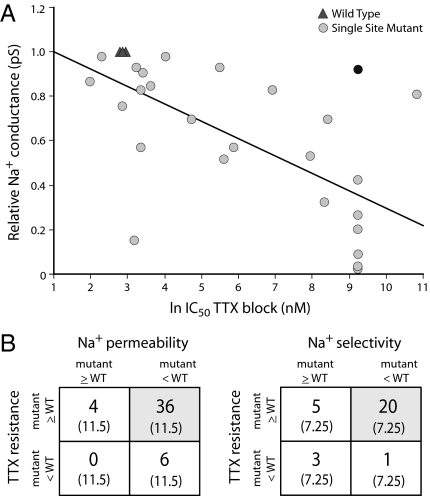

Fig. 3.

Tradeoff between TTX sensitivity and sodium channel performance at the molecular level. Mutations that improve TTX resistance tend to reduce Na+ permeability and Na+ selectivity. (A) Linear regression (r2 = 0.417; F-value = 20.739; P < 0.0001) of the amount of TTX (in nM) required to inhibit peak Na+ current by 50% (IC50) against single-channel conductance (pS) in wild-type (triangles) and single-site Nav mutants (circles). The dark circle is a change to the DIII selectivity filter that completely abolishes Na+ selectivity and would be lethal. Data from literature (refs. 45, 65, and 69; see text). (B) χ2 analysis of a larger set of mutants scored as either augmenting or diminishing TTX resistance and Na+ permeability or Na+ selectivity compared with wild-type sodium channels. In both cases, there is a statistical excess of mutants that increase TTX resistance but decrease Na+ permeability (χ2 = 71.22, P < 0.0001) or Na+ selectivity (χ2 = 31.00, P < 0.0001) compared with null expectations (gray boxes; expected counts are given in parentheses). Data from literature (refs. 41, 43–45, 65–70, and 74–81; see text and Table S1).

Methods

Bioassays.

To provide a phylogenetic perspective on the evolution of elevated TTX resistance in snakes and to aid in our interpretation of Nav1.4 sequence data, we collected TTX-resistance data from a diverse sample of colubroid snakes. We collected data from 16 snake species (n = 116 individuals) representing most of the major colubroid lineages (57, 58) and from one lizard outgroup taxon (n = 5). We augmented these data with results from some of our other work (19, 20, 42, 59) to provide the most complete picture of TTX resistance in squamate reptiles to date (29 species; n = 424) (Fig. S1).

We measured TTX resistance using a bioassay of whole-organism performance (17, 60). We first established an individual's “baseline speed” by racing it down a 4-m racetrack equipped with infrared sensors that clock sprint speed over 0.5-m intervals. We ran each snake twice and averaged the speed of the two time trials to obtain an individual's baseline crawl speed. Following a day of rest, we gave each snake an i.p. injection of a known, mass-adjusted dose of TTX (Sigma). Thirty minutes after injection we raced snakes on the track to determine postinjection speed. We repeated this process, resting snakes for a day then increasing the dose of TTX (0.5 μg, 1 μg, 2 μg, 5 μg, and 10 μg) and running snakes, up to five total sequential TTX tests per snake.

We scored resistance as the reduction of an individual's baseline sprint speed following an injection of TTX (postinjection speed/baseline speed). Snakes greatly impaired by TTX slither at only a small proportion of their normal speed, whereas those unaffected by a dose of TTX crawl at 100% of their baseline speed. We then calculated a population (or species) dose–response curve from individual responses to the serial TTX injections using a simple linear regression (see ref 61). From this regression model we estimated the 50% dose, defined as the amount of TTX required to reduce speed of the average snake to 50% of its baseline. This measure is analogous to a 50% inhibition concentration (IC50). Because TTX resistance is related to body size (60, 61), we transformed doses into mass-adjusted mouse units, the amount of TTX (in mg) required to kill a 20-g mouse in 10 min (see ref 61.). This correction allows us to compare TTX resistance directly between individuals, populations, or species. Further details of the bioassay and information on captive care of snakes can be found elsewhere (17, 61).

Sequence Data.

To determine whether snake lineages have independently acquired TTX resistance through similar genetic modifications, we examined DNA sequence variation in portions of the four domains (DI–DIV) that code for the P-loops of Nav1.4. We sequenced snakes known to prey on TTX-laden amphibians, their sister groups, and additional taxa to provide a robust phylogenetic perspective (75 species; n = 138) (Fig. S1). We focused on the P-loops because TTX interacts with residues of the outer pore (see refs. 35–38), and changes in P-loop sites appear to be responsible for TTX resistance in animals (32, 34, 39–42, 62).

We isolated and purified genomic DNA from muscle or liver tissue with the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Inc.). We amplified the four P-loops of Nav1.4 using primers we designed specifically to capture the regions between the S5 and S6 transmembrane segments that form the outer pore (6). We cleaned amplified products using the ExcelaPure PCR Purification Kit (Edge Biosystems) and used purified template in cycle-sequencing reactions with Big Dye chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Following an isopropanol/ethanol precipitation, we ran cycle-sequenced products on an ABI 3130 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). We sequenced all samples in both directions to obtain overlapping reads. For some species this bidirectional sequencing was difficult for DI and DIII because of long introns, and we resequenced these individuals two additional times to confirm exon sequences. We also reamplified and resequenced samples showing adaptive replacements to validate P-loop variation.

We edited and aligned sequences in Sequencher 4.2 (Gene Codes Corp.) and translated coding regions into amino acid sequences using MacClade 4.08 (63). We deposited all sequences in GenBank (accession nos. FJ570810–FJ571064, GQ154075–GQ154084, and JQ687537–JQ687861).

Visualizing P-Loop Replacements and TTX in Nav1.4.

We used the 3D model of the outer pore of the sodium channel developed by Lipkind and Fozzard (35) based on structural homology between rat Nav1.4 P-loops and the crystal structure of the pore region of the bacterial potassium channel (KcsA) and refined with data on toxin binding and the biophysics of Na+ permeation (35, 36). Lipkind and Fozzard kindly provided the Protein Database coordinates to their model, which we used in UCSF Chimera (64) to visualize the P-loop replacements in TTX-resistant snakes. Finally, we used UCSF Chimera to visualize TTX occluding the outer pore, following the current model of docking orientation (36). Note that Th. atratus A1281P cannot be visualized because this replacement is just C-terminal to the DIII model coordinates.

Assessing Bias in Nav1.4 Mutations.

We determined whether the pattern of mutations we observed in snakes is clustered or follows a random distribution. If the observed mutations are not distributed randomly among P-loop sites but instead are clustered, then we have evidence that the genetic response of snakes has been narrowed. We tallied the number of times a site was hit by a mutation for two sets of potentially available sites: (i) all sites of the four P-loops (n = 96) (following ref. 35) or (ii) only sites experimentally verified to reduce TTX sensitivity twofold versus wild type and/or shown to influence TTX binding significantly in protein models (n = 33) (32, 37–41, 43, 45, 62, 65–71) but also including sites with parallel substitutions between snakes and pufferfish still unstudied (n = 2) (39–41). We then used a simple binomial test to compare the distribution of our data against the null expectation of a Poisson distribution. Note that we counted the I1566V replacement seen in both Benton and Willow Creek Th. sirtalis only once, because we assume this replacement appears in these populations because of common descent (i.e., does not represent independent replicated events). We calculated the mean and variance of our samples and then the coefficient of dispersion (CD = variance/mean). In a Poisson distribution the mean and variance are roughly equal (CD = 1), but in a clumped distribution the variance should be much greater than the mean (CD > 1) (72). Because the CD is approximately χ2 distributed (72), we calculated χ2 scores for our CD measures to obtain P values against the random expectation (CD = 1). Here χ2 = I(n − 1) where I is our CD and n − 1 is the degrees of freedom (72), in this case the number of sites minus 1.

Assessing Tradeoffs in Nav1.4.

Sodium channels are highly specialized proteins, and the amino acids that form the outer pore and selectivity filter interact in complex ways to create the optimal environment for the selective permeation of Na+ ions (16). However, the same P-loop residues that permit selectivity and permeability of Na+ also interact strongly with TTX through a combination of hydrogen and ionic bonds, steric attraction, and cation–π interaction (36, 37, 43–45, 66, 69, 71, 73). Therefore, changes that reduce the affinity of TTX to the outer pore also might negatively impact the molecular sieving of the sodium channel. If antagonistic pleiotropy exists within Nav1.4, then we should find convergence at the molecular level, because the pool of replacements that can reduce TTX binding and preserve channel function probably is limited. We quantified this potential tradeoff between TTX resistance and sodium channel function to understand whether constraints have influenced molecular evolution in TTX-resistant snakes.

We evaluated the potential tradeoff between TTX resistance and two essential functions of the sodium channel that are determined by the molecular architecture of the outer pore: (i) Na+ permeability and (ii) Na+ selectivity. We searched the literature for electrophysiological studies that measured the effects of individual replacements (via site-directed mutagenesis and ex vivo expression) on TTX block, Na+ permeability, or Na+ selectivity. Most studies measured or reported these variables in different ways (e.g., different cations were tested for Na+ selectivity), and few examined the effects of the same replacement on each of these three variables. Therefore, we simply scored a replacement as producing a positive or negative effect on TTX resistance (predictor variable) and either Na+ permeability or Na+ selectivity (response variables) as follows: we scored a replacement as positive (1) if it produced an effect as well or better than the wild type; we scored a replacement as negative (0) if it produced a statistically worse effect than the wild type. Using this scheme, we tallied 46 mutants for both TTX resistance and Na+ permeability (41, 43–45, 66, 67, 69, 70, 74, 75) and 29 mutants for TTX resistance and Na+ selectivity (43, 65–68, 74–81) (summarized in Table S1). We then determined whether either Na+ permeability or Na+ selectivity is statistically independent of TTX resistance using a simple χ2 test under the null assumption that a mutation could affect traits along both axes with equal probability (expected ratio 1:1:1:1) (Fig. 3).

We also performed a regression analysis on TTX resistance against Na+ permeability using data from three site-directed mutagenesis studies that collected and reported comparable data (45, 65, 69). Here, the data on TTX sensitivity are the concentrations of TTX (in nM) required to reduce peak Na+ current by 50% (IC50) in the wild-type and single-mutant channels, and the data on Na+ permeability are measures of single-channel conductance (pS). We log-transformed the TTX data and adjusted the Na+ conductance data of each study by setting wild-type measures to 1 and scaling the conductance values of each mutant to its respective wild type. We then performed a linear regression of these data (n = 31) using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc.) (Fig. 3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Sinclair, S. Boback, P. Ducey, B. Christman, D. Mulcahy, B. Williams, and M. Edgehouse for field assistance; D. Schultz (Mfezi LLC), A. de Queiroz, and C. Fontenot for specimens; A. Mortensen, J. Scoville, and A. Wilkinson for captive care; J. Vindum and M. Koo (California Academy of Science) and J. Campbell and C. Franklin (University of Texas at Arlington) for curating specimens; J. McGuire and C. Cicero (Museum of Vertebrate Zoology), J. Vindum and R. Drewes (California Academy of Science), D. Dittmann and C. Austin (Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science), J. Campbell and C. Franklin (University of Texas at Arlington), F. Burbrink, M. Donnelly, R. Maneyro, and F. Kraus for tissues; J. Campbell, W. Flaxington, P. Janzen, B. Kubicki, and S. Li for photographs; M. Matocq and J. Chuckalovcak for laboratory aid; P. Murphy for statistical advice; H. Fozzard and G. Lipkind for Nav model coordinates; K. Davis of Notre Dame Center for Research Computing for protein visualization; and H. Greene, M. Matocq, A. de Queiroz, C. Evilia, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful discussions. We thank the California Department of Fish and Game, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, and Utah State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for permits. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants DEB-0315172 and DEB-0922251, by National Geographical Society Grant 7531-03, and by Utah State University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. FJ570810–FJ571064, GQ154075–GQ154084, and JQ687537–JQ687861). The physical specimens reported in this paper have been deposited as vouchers in the herpetology collections of the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) or University of Texas at Arlington (UTA).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1113468109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Miller SP, Lunzer M, Dean AM. Direct demonstration of an adaptive constraint. Science. 2006;314:458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1133479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreich DM, Delaney NF, Depristo MA, Hartl DL. Darwinian evolution can follow only very few mutational paths to fitter proteins. Science. 2006;312:111–114. doi: 10.1126/science.1123539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevin LM, Martin G, Lenormand T. Fisher's model and the genomics of adaptation: Restricted pleiotropy, heterogeneous mutation, and parallel evolution. Evolution. 2010;64:3213–3231. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christin P-A, Weinreich DM, Besnard G. Causes and evolutionary significance of genetic convergence. Trends Genet. 2010;26:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streisfeld MA, Rausher MD. Population genetics, pleiotropy, and the preferential fixation of mutations during adaptive evolution. Evolution. 2011;65:629–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern DL, Orgogozo V. Is genetic evolution predictable? Science. 2009;323:746–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1158997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maynard Smith J, et al. Developmental constraints and evolution. Q Rev Biol. 1985;60:265–287. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wake DB. Homoplasy: The result of natural selection, or evidence of design limitations? Am Nat. 1991;138:543–567. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brakefield PM. Evo-devo and constraints on selection. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll SB, Grenier JK, Weatherbee SD. From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DePristo MA, Weinreich DM, Hartl DL. Missense meanderings in sequence space: A biophysical view of protein evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:678–687. doi: 10.1038/nrg1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gompel N, Prud'homme B. The causes of repeated genetic evolution. Dev Biol. 2009;332:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly JW. Marine toxins and nonmarine toxins: Convergence or symbiotic organisms? J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1211–1215. doi: 10.1021/np040016t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanifin CT. The chemical and evolutionary ecology of tetrodotoxin (TTX) toxicity in terrestrial vertebrates. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:577–593. doi: 10.3390/md8030577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medinsky MA, Klaassen CD. Toxicokinetics. In: Klaassen CD, editor. Casarett and Doull's Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd Ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodie ED, Jr, Ridenhour BJ, Brodie ED., III The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: Hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts. Evolution. 2002;56:2067–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanifin CT, Brodie ED, Jr, Brodie ED., III Phenotypic mismatches reveal escape from arms-race coevolution. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brodie ED., Jr Investigations on the skin toxin of the adult Rough-skinned Newt, Taricha granulosa. Copeia. 1968;1968:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brodie ED, III, et al. Parallel arms races between garter snakes and newts involving tetrodotoxin as the phenotypic interface of coevolution. J Chem Ecol. 2005;31:343–356. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-1345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiseman KD, Pool AC. Thamnophis couchii (Sierra garter snake): Predator-prey interaction. Herpetol Rev. 2007;38:344. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene RR, Feldman CR. Thamnophis atratus atratus. Diet. Herpetol Rev. 2009;40:103–104. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YH, Brown GB, Mosher FA, Fuhrman FA. Tetrodotoxin: Occurrence in atelopid frogs of Costa Rica. Science. 1975;189:151–152. doi: 10.1126/science.1138374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daly JW, Gusovsky F, Myers CW, Yotsu-Yamashita M, Yasumoto T. First occurrence of tetrodotoxin in a dendrobatid frog (Colostethus inguinalis), with further reports for the bufonid genus Atelopus. Toxicon. 1994;32:279–285. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers CW, Daly JW, Malkin B. A dangerously toxic new frog (Phyllobates) used by Embera Indians of Western Columbia, with discussion of blowgun fabrication and dart poisoning. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 1978;161:309–365. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene HW. Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yotsu M, Iorizzi M, Yasumoto T. Distribution of tetrodotoxin, 6-epitetrodotoxin, and 11-deoxytetrodotoxin in newts. Toxicon. 1990;28:238–241. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(90)90419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori A, Moriguchi H. Food habits of the snakes in Japan: A critical review. Snake. 1988;20:98–113. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goris RC, Maeda N. Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Japan. Malabar, FL: Krieger; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanu MB, Mahmud Y, Tsuruda K, Arakawa O, Noguchi T. Occurrence of tetrodotoxin in the skin of a rhacophoridid frog Polypedates sp. from Bangladesh. Toxicon. 2001;39:937–941. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao E, Huang M, Zong Y, editors. Fauna Sinica: Reptilia. Vol 3 Squamata, Serpentes. Beijing: Science Press; 1998. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geffeney SL, Fujimoto E, Brodie ED, III, Brodie ED, Jr, Ruben PC. Evolutionary diversification of TTX-resistant sodium channels in a predator-prey interaction. Nature. 2005;434:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geffeney SL, Brodie ED, Jr, Ruben PC, Brodie ED., III Mechanisms of adaptation in a predator-prey arms race: TTX-resistant sodium channels. Science. 2002;297:1336–1339. doi: 10.1126/science.1074310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman CR, Brodie ED, Jr, Brodie ED, III, Pfrender ME. Genetic architecture of a feeding adaptation: Garter snake (Thamnophis) resistance to tetrodotoxin bearing prey. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277:3317–3325. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA. KcsA crystal structure as framework for a molecular model of the Na(+) channel pore. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8161–8170. doi: 10.1021/bi000486w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fozzard HA, Lipkind GM. The tetrodotoxin binding site is within the outer vestibule of the sodium channel. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:219–234. doi: 10.3390/md8020219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS. Modeling P-loops domain of sodium channel: Homology with potassium channels and interaction with ligands. Biophys J. 2005;88:184–197. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS. Possible roles of exceptionally conserved residues around the selectivity filters of sodium and calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2998–3006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venkatesh B, et al. Genetic basis of tetrodotoxin resistance in pufferfishes. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2069–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jost MC, et al. Toxin-resistant sodium channels: Parallel adaptive evolution across a complete gene family. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1016–1024. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maruta S, Yamaoka K, Yotsu-Yamashita M. Two critical residues in p-loop regions of puffer fish Na+ channels on TTX sensitivity. Toxicon. 2008;51:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feldman CR, Brodie ED, Jr, Brodie ED, III, Pfrender ME. The evolutionary origins of beneficial alleles during the repeated adaptation of garter snakes to deadly prey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13415–13420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901224106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penzotti JL, Fozzard HA, Lipkind GM, Dudley SC., Jr Differences in saxitoxin and tetrodotoxin binding revealed by mutagenesis of the Na+ channel outer vestibule. Biophys J. 1998;75:2647–2657. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choudhary G, Yotsu-Yamashita M, Shang L, Yasumoto T, Dudley SC., Jr Interactions of the C-11 hydroxyl of tetrodotoxin with the sodium channel outer vestibule. Biophys J. 2003;84:287–294. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74849-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terlau H, et al. Mapping the site of block by tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin of sodium channel II. FEBS Lett. 1991;293:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saporito RA, Donnelly MA, Spande TF, Garraffo HM. A review of chemical ecology in poison frogs. Chemoecology. 2011;21:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gusovsky F, Rossignol DP, McNeal ET, Daly JW. Pumiliotoxin B binds to a site on the voltage-dependent sodium channel that is allosterically coupled to other binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1272–1276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang SY, Wang GK. Point mutations in segment I-S6 render voltage-gated Na+ channels resistant to batrachotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2653–2658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li HL, Hadid D, Ragsdale DS. The batrachotoxin receptor on the voltage-gated sodium channel is guarded by the channel activation gate. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:905–912. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du Y, Garden DP, Wang L, Zhorov BS, Dong K. Identification of new batrachotoxin-sensing residues in segment IIIS6 of the sodium channel. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13151–13160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gusovsky F, Padgett WL, Creveling CR, Daly JW. Interaction of pumiliotoxin B with an “alkaloid-binding domain” on the voltage-dependent sodium channel. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:1104–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schluter D. Adaptive radiation along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution. 1996;50:1766–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnold SJ. Constraints on phenotypic evolution. Am Nat. 1992;140(Suppl 1):S85–S107. doi: 10.1086/285398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnold SJ, Pfrender ME, Jones AG. The adaptive landscape as a conceptual bridge between micro- and macroevolution. Genetica. 2001;112:9–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schluter D, Clifford EA, Nemethy M, McKinnon JS. Parallel evolution and inheritance of quantitative traits. Am Nat. 2004;163:809–822. doi: 10.1086/383621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiamvimonvat N, Pérez-García MT, Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Control of ion flux and selectivity by negatively charged residues in the outer mouth of rat sodium channels. J Physiol. 1996;491:51–59. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiens JJ, et al. Branch lengths, support, and congruence: Tsting the phylogenomic approach with 20 nuclear loci in snakes. Syst Biol. 2008;57:420–431. doi: 10.1080/10635150802166053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pyron RA, et al. The phylogeny of advanced snakes (Colubroidea), with discovery of a new subfamily and comparison of support methods for likelihood trees. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;58:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motychak JE, Brodie ED, Jr, Brodie ED., III Evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: preadaptation and the evolution of tetrodotoxin resistance in garter snakes. Evolution. 1999;53:1528–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb05416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brodie ED, III, Brodie ED., Jr Tetrodotoxin resistance in garter snakes: An evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey. Evolution. 1990;44:651–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ridenhour BJ, Brodie ED, III, Brodie ED., Jr Resistance of neonates and field-collected garter snakes (Thamnophis spp.) to tetrodotoxin. J Chem Ecol. 2004;30:143–154. doi: 10.1023/b:joec.0000013187.79068.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Du Y, Nomura Y, Liu Z, Huang ZY, Dong K. Functional expression of an arachnid sodium channel reveals residues responsible for tetrodotoxin resistance in invertebrate sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33869–33875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maddison DR, Maddison WP. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2005. MacClade: Analysis of phylogeny and character evolution. v. 4.08. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Backx PH, Yue DT, Lawrence JH, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Molecular localization of an ion-binding site within the pore of mammalian sodium channels. Science. 1992;257:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1321496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kontis KJ, Goldin AL. Site-directed mutagenesis of the putative pore region of the rat IIA sodium channel. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;43:635–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pérez-García MT, Chiamvimonvat N, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Structure of the sodium channel pore revealed by serial cysteine mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen S-F, Hartmann HA, Kirsch GE. Cysteine mapping in the ion selectivity and toxin binding region of the cardiac Na+ channel pore. J Membr Biol. 1997;155:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s002329900154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamagishi T, Li RA, Hsu K, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF. Molecular architecture of the voltage-dependent Na channel: Functional evidence for alpha helices in the pore. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:171–182. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carbonneau E, Vijayaragavan K, Chahine M. A tryptophan residue (W736) in the amino-terminus of the P-segment of domain II is involved in pore formation in Nav1.4 voltage-gated sodium channels. Eur J Physiol. 2002;445:18–24. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scheib H, et al. Modeling the pore structure of voltage-gated sodium channels in closed, open, and fast-inactivated conformation reveals details of site 1 toxin and local anesthetic binding. J Mol Model. 2006;12:813–822. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krebs CJ. Ecological Methodology. 2nd Ed. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin-Cummings; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Santarelli VP, Eastwood AL, Dougherty DA, Horn R, Ahern CA. A cation-π interaction discriminates among sodium channels that are either sensitive or resistant to tetrodotoxin block. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8044–8051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chiamvimonvat N, Pérez-García MT, Ranjan R, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Depth asymmetries of the pore-lining segments of the Na+ channel revealed by cysteine mutagenesis. Neuron. 1996;16:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Favre I, Moczydlowski E, Schild L. On the structural basis for ionic selectivity among Na+, K+, and Ca2+ in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biophys J. 1996;71:3110–3125. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79505-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li RA, Vélez P, Chiamvimonvat N, Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Charged residues between the selectivity filter and S6 segments contribute to the permeation phenotype of the sodium channel. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:81–92. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun Y-M, Favre I, Schild L, Moczydlowski E. On the structural basis for size-selective permeation of organic cations through the voltage-gated sodium channel. Effect of alanine mutations at the DEKA locus on selectivity, inhibition by Ca2+ and H+, and molecular sieving. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:693–715. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsushima RG, Li RA, Backx PH. Altered ionic selectivity of the sodium channel revealed by cysteine mutations within the pore. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:463–475. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sunami A, Glaaser IW, Fozzard HA. A critical residue for isoform difference in tetrodotoxin affinity is a molecular determinant of the external access path for local anesthetics in the cardiac sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2326–2331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030438797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leffler A, Herzog RI, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG, Cummins TR. Pharmacological properties of neuronal TTX-resistant sodium channels and the role of a critical serine pore residue. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:454–463. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee CH, Jones DK, Ahern C, Sarhan MF, Ruben PC. Biophysical costs associated with tetrodotoxin resistance in the sodium channel pore of the garter snake, Thamnophis sirtalis. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2011;197:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s00359-010-0582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.