Abstract

Study Objectives:

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) improves sleep and quality of life for both patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and their spouses. However, few studies have investigated spousal involvement in treatment adherence. Aims of this observational study were to assess perceptions of spousal involvement and evaluate associations between involvement and adherence.

Methods:

Spousal involvement in CPAP adherence was assessed in 23 married male OSA patients after the first week of treatment. At 3 months, 16 participants completed a second assessment of spousal involvement. Types of involvement assessed included positive (e.g., encouraging), negative (e.g., blaming), collaboration (e.g., working together), and one-sided (e.g., asking). An interpersonal measure of supportive behaviors was also administered at 3 months to evaluate the interpersonal qualities of spousal involvement types. Objective CPAP adherence data were available for 14 participants.

Results:

Average frequency of spousal involvement ratings were low for each involvement type and only negative spousal involvement frequency decreased at 3 month follow-up (p = 0.003). Perceptions of collaborative spousal involvement were associated with higher CPAP adherence at 3 months (r = 0.75, p = 0.002). Positive, negative and one-sided involvement were not associated with adherence. Collaborative spousal involvement was associated with moderately warm and controlling interpersonal behaviors (affiliation, r = 0.55, p = 0.03, dominance r = 0.47, p = 0.07).

Conclusions:

Patients reported low frequency but consistent and diverse perceptions of spousal involvement in CPAP over the first 3 months of treatment. Perceptions of collaborative spousal involvement were the only type associated with adherence and represent moderately warm and controlling interpersonal behavior. Interventions to increase spousal collaboration in CPAP may improve adherence.

Citation:

Baron KG; Gunn HE; Czajkowski LA; Smith TW; Jones CR. Spousal involvement in CPAP: does pressure help? J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8(2):147-153.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure, adherence, relationship quality, social support

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is present in 2% to 4% of middle-aged adults and causes intermittent hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, and changes in sleep architecture.1 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the recommended treatment for the majority of patients with OSA and has been shown to improve daytime sleepiness2 and mood,3 and reduce risk for coronary events in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).4,5 In addition to improving health and quality of life for patients, spouses of OSA patients also report benefits from the patient using CPAP, including decreased sleepiness and improved sleep quality and relationship satisfaction.6–9 Despite these benefits, 46% to 83% of patients do not adhere to CPAP treatment, which means studying factors associated with adherence to CPAP are a necessary and important task.10,11

Frequently, patients report the spouse is a main factor in their decision to seek treatment for OSA.12,13 However, only a handful of studies have evaluated the process of spousal involvement in CPAP adherence and whether such involvement is beneficial. Of those that have examined spousal involvement in CPAP adherence, the findings are mixed. Some studies have reported that spousal involvement is associated with better adherence and others have reported possible negative effects of spousal involvement. Sharing a bed with a spouse or partner has been associated with higher adherence in two studies.8,14 However, higher marital conflict and seeking treatment because of a spouse (rather than self-referral) have been associated with poorer adherence.15,16

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Patients often report spousal influence on treatment-seeking in OSA but few studies have systematically evaluated spousal involvement in treatment. The goal of this study was to evaluate how spouses are involved in CPAP treatment and the effects of percieved involvement on adherence to continuous positive airway pressure.

Study Impact: This study will inform sleep professionals about the ways spouses are involved in treatment and results suggest that increasing collaborative spousal involvement in CPAP use may improve adherence.

The discrepancy in these findings may be due to the specific nature of spousal interactions with respect to CPAP use. In other words, the type of involvement may be integral to CPAP adherence. At this point, no study has systematically evaluated spousal involvement in CPAP. Elsewhere in the health literature, spousal involvement has been related to improvements in a range of health behaviors, including diet, exercise, and visiting the doctor, particularly when the involvement is viewed as positive and collaborative.17–21 The most effective types of spousal involvement include providing encouragement or helping make changes to facilitate the behavior. On the other hand, negative types of involvement, such as criticism, have been associated with psychological distress or ignoring the spouses' request for behavior change.18,22–25 In one study, feeling supported by the spouse has been associated with higher CPAP adherence during the subsequent night in patients with more severe OSA.26 However, the methodology used in the study (daily questionnaires) limited the number of spousal behaviors assessed, and it was not clear what type of supportive behavior was most beneficial. Further research to describe and understand how spouses are involved in improving CPAP treatment is vital to the design of couples-based interventions, as well as for providing evidence-based recommendations to OSA patients and their spouses.

The goal of this observational longitudinal study was to evaluate the frequency and nature of spousal behaviors aimed at influencing CPAP adherence over the first 3 months of treatment. The second aim was to determine if perceptions of spousal involvement are associated with adherence. We hypothesized that more frequent perceptions of positive and collaborative spousal involvement aimed at CPAP adherence would be associated with higher adherence and that more frequent perceptions of negative involvement would predict poorer adherence.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from patients undergoing overnight diagnostic polysomnograms at an academic sleep disorders center. Eligibility criteria included the following: age 18-65 years, male gender, diagnosis of OSA, married or living with a romantic partner ? 1 year, and CPAP naive. Exclusionary criteria included the following: spousal use of CPAP, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, oxygen therapy, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, psychosis, and use of other concurrent treatments for OSA (bariatric surgery, upper airway surgery, and oral appliance). Patients with comorbid sleep disorders (insomnia n = 2, periodic limb movements and/or restless leg syndrome n = 8) were not excluded. The protocol was approved by the University of Utah institutional review board, and all patients completed written informed consent.

Procedure

All patients underwent 2 overnight polysomnograms: a diagnostic study and a CPAP titration. Patients were enrolled in the study after the diagnostic study confirmed an OSA diagnosis. All patients attended a physician's appointment for education and treatment planning as well as an individual 30-min mask fitting and education session with a sleep technician prior to the CPAP titration. The type of CPAP mask was determined by the patient preference and assessment of fit by the technician. Brand of CPAP machine, use of heated humidification, and settings were determined by the sleep physician. Patients completed baseline questionnaires (demographics, relationship quality) on the evening of their CPAP titration. Spousal involvement was measured using a questionnaire administered by mail 7-10 days after starting CPAP to assess spousal involvement in the first week of CPAP use. At 3 months, patients were contacted again to complete follow-up measures (spousal involvement and interpersonal behavior associated with CPAP). CPAP adherence data were downloaded by the patients' home care company at 3 months. Multiple attempts were made by the home care company and research team to contact patients missing adherence reports and arrange to retrieve the adherence data by mail or in person.

Measures

Demographics were collected prior to treatment initiation including self-reported age, marital status, income, and employment status.

Relationship quality was measured by the support and conflict subscales of the Quality of Relationship Inventory (QRI).27 The support subscale contains items related to emotional support in the marriage, such as “To what extent could you count on your spouse for help with a problem?” and “To what extent could you count on this person to listen to you when you are very angry at someone else?” The conflict subscale contains items related to the frequency and extent of marital conflict, such as, “How angry does your spouse make you feel?” and “How often do you have to work hard to avoid conflict with your spouse?” Subscales were scored as the average of the 7 support items and average of the 12 conflict items. Cronbach's α for the support and conflict subscales ranged from the 0.70s to 0.90s, indicating adequate internal consistency; test-retest reliability correlations ranged from 0.48 to 0.79.28,29

Perceptions of spousal involvement in CPAP was measured using an adapted version of a 25-item measure of strategies couples use to influence each other's health behavior.30,31 The original measure was developed using existing power/control measures as well as focus groups of couples discussing influencing each other's health, then subscales were assigned by 6 independent raters. In this study, we excluded 3 items from this measure because these items were not relevant to CPAP treatment (e.g., offering to change with the patient, making the change for the patient). Then, we adapted the remaining items in the scale to specifically reference perceptions of spousal efforts to influence CPAP use. Patients rated how often their spouse used each strategy over the past week. Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (often, several times per day). We also re-named the subscale titles for easier interpretation (without changing the scoring of the measure). Subscales included collaborative (e.g., changed something at home, discussed CPAP), one-sided (e.g., gave space, dropped hints), positive (e.g., told me she was happy), and negative (e.g., tried to evoke negative emotion, withdrew). Some behaviors were combinations of these categories. For example, helping make changes at home to get the participant to use CPAP is considered positive and collaborative, whereas making the patient scared of the consequences of not using CPAP is considered negative and one-sided. Therefore, categories were not mutually exclusive and many items were coded in two categories. Cronbach's α for this scale (in the original form) has been reported as adequate (0.72 to 0.78.)30 In our sample, the Cronbach's α for the 4 scales was similar (0.72-0.80). The adapted measure was administered 7-10 days after initiation of CPAP treatment and at 3-month follow-up.

Patients completed an adapted version of the Support Actions Scale-C32 at 3-month follow-up as a measure of interpersonal qualities of behaviors associated with CPAP use. This measure was included to provide more specific information on the nature of interpersonal behaviors that were occurring between spouses in regards to CPAP. Based on the interpersonal circumplex, the measure included items that measure supportive behavior based on the 2 main axes of interpersonal behavior: affiliation and control.33 Thirty-two items of the 64-item measure were selected for use in this study. Items were selected by factor loadings on the octant scores and their relevance to transactions regarding CPAP. The instructions for this measure were adapted to interactions regarding CPAP use. Responses ranged from A (very unlikely) to E (very likely). Two dimension (affiliation and control) scores were computed. Excellent structural integrity and construct validity of the original 64-item measure with other measures of social support and circumplex measures of interpersonal behavior have been reported.32

Adherence to CPAP was measured using a memory card located in the CPAP apparatus which recorded the number of minutes per night the CPAP machine was turned on with the mask in place. Adherence downloads were ordered by the clinic's CPAP follow-up technician approximately 90 days after patients began treatment. Downloads were conducted by mail or in person by the patients' durable medical equipment company. Adherence was defined as average hours of CPAP use per night.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (v. 19). Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the sample characteristics, frequency and intensity of spousal involvement subscales. Change in spousal involvement from week 1 to 3-month follow-up was evaluated using paired t-tests. Correlations between spousal involvement week 1 and adherence at follow-up were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficients. Significance was defined as p values < 0.05 on two tailed tests.

RESULTS

Participants

Twenty-three patients initially completed questionnaires before starting CPAP and the spousal involvement measure 7-10 days after beginning CPAP treatment. Of those 23 patients, 16 responded to a request to complete a second spousal involvement measure 3 months after starting CPAP. Participant characteristics at week 1 are listed in Table 1. Average age was 47.3 years (SD 11.8) and average disease severity measured by the apnea hypopnea Index (AHI) was 36.5 (SD 26.4). All were married and except one participant (who was engaged and living with his fiancée), and all were white. There were no differences in age, AHI, adherence, relationship quality, or level of spousal involvement over the first week of treatment between patients who responded at 3 months and those who did not complete the second assessment (Table 2). Objective CPAP adherence data at 3 months was available for 14 patients (n = 12 patients who completed baseline and follow-up spousal involvement measures, and n = 2 patients with only baseline spousal involvement measures). Average adherence was 5.6 h (SD 1.3), and average number of days recorded was 88.4 (SD 45.9). Missing adherence data were due to inability to contact the participant to arrange a download of adherence data (n = 5), lack of placement of adherence card (n = 2), lack of adherence recording capabilities in the CPAP machine (n = 1), and moving out of state (n = 1).

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics, N = 23

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 47.4 (11.8) years |

| Race, N (%) | |

| White | 22 (96) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (4) |

| Education, N (%) | |

| < 12 grade | 1 (4) |

| some college or associate’s degree | 10 (47) |

| bachelor’s degree | 8 (36) |

| graduate degree or more | 3 (13.6) |

| Length of Marriage, Mean (SD) | 18.8 (12.0) years |

| Share bed with spouse every night, N (%) | 18 (78) |

| Apnea hypopnea index, Mean (SD) | 36.5 (26.4) events/h |

| Range | 5-97 events/h |

| Adherence at 3 months*, Mean (SD) | 5.6 (1.3) h |

| Range | 3.6-7.9 h |

Objective adherence data were available for 14 patients with baseline data.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics according to follow-up

| Both time points N = 16 | Baseline only N = 7 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 46.5 (10.9) years | 49.3 (14.3) years |

| Length of Marriage, Mean (SD) | 19.6 (11.6) years | 16.8 (14.1) years |

| Share bed with spouse every night, N (%) | 14 (88) | 4 (67)* |

| Apnea Hypopnea Index, Mean (SD) | 32.5 (19.2) events/h | 47.1 (40.7) events/h |

| Range | 5-62.7 events/h | 9.1-97.3 events/h |

| Adherence at 3 months**, Mean (SD) | 5.5 (1.2) h | 6.0 (2.4) |

| Range | 3.6-7.9 h | 4.3-7.6 h |

| Self report of “good adherence” to physician at follow-up*** | 14 (87) | 5 (83) |

| Relationship Quality | ||

| Support | 25.1 (2.7) | 23.3 (5.3) |

| Conflict | 24.6 (4.6) | 27.1 (8.3) |

| Total Baseline Tactics Score (all scales combined) | 5.8 (4.5) | 4.9 (4.6) |

p values are > 0.20 for all variables.

One participant did not respond to this question.

Objective adherence data were available for 12 of 16 patients in the group with both time points and 2 of 7 patients with baseline spousal involvement measures only.

Notes from follow-up with a sleep physician were available for 16 of 16 participants with both time points and 6 of 7 participants with baseline only.

Characteristics of Perceived Spousal Involvement

Ratings of perceived spousal involvement from week 1 are listed in Table 3. Results demonstrate a range of commonly endorsed items from all subscales. Of the 25 items on the spousal involvement scale, the most commonly rated items were from the positive scale, such as “Changed something at work or home to get me to use CPAP,” reported by 83% of patients with an average rating of 2.3 (approximately 1-2 times in the past week), and “Told me she was happy I was using CPAP,” reported by 65% of patients with an average rating of 2.2 (approximately 1-2 times in the past week). However, negative items were also endorsed by many patients. “Tried to make me scared of the consequences of not using CPAP” was reported by 57% of patients and had an average rating of 1.9 (approximately 1-2 times in the past week).

Table 3.

Spousal involvement items and ratings week 1, N = 23

| Item | % Reporting Item at least once | Average Frequency Rating (1-4) | Positive or Negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative Items | |||

| Changed something at home or work to get me to use CPAP | 83 | 2.3 | + |

| Told me he or she was happy I was using CPAP | 65 | 2.2 | + |

| Repeatedly reminded me to use CPAP | 13 | 1.2 | + |

| Discussed using CPAP | 13 | 1.2 | + |

| Pointed out my responsibilities to the family in order to get me to use CPAP | 13 | 1.2 | + |

| Persuaded me to use CPAP | 9 | 1.1 | + |

| Bargained with me to use CPAP | 0 | 1 | + |

| One-Sided Items | |||

| Gave me space, showed patience in order to get me to use CPAP | 57 | 2.1 | + |

| Tried to make me scared of the consequences of not using CPAP | 57 | 1.9 | − |

| Made a suggestion that I use CPAP | 40 | 1.7 | + |

| Withdrew, became silent to get me to use CPAP | 40 | 1.5 | − |

| Dropped hints that I should use CPAP | 35 | 1.4 | − |

| Asked me to use CPAP | 30 | 1.4 | + |

| Told me I would use it if I cared about him or her | 30 | 1.3 | − |

| Praise or compliment me for using CPAP | 22 | 1.3 | + |

| Told me he or she was unhappy I wasn’t using CPAP | 9 | 1.2 | − |

| Stated how important me using CPAP was to him or her | 9 | 1.1 | + |

| Tried to involve other people in order to get me to use CPAP | 9 | 1.1 | Neither |

| Tried to get me to use CPAP by reasoning/logic | 5 | 1.0 | + |

| Compared me to other people who are not using CPAP | 4 | 1.0 | − |

| Pointed out other people who were using CPAP | 4 | 1.1 | + |

| Neither Collaborative or One-Sided | |||

| Used humor or made jokes about using CPAP | 4 | 1.0 | + |

Change in Perceived Spousal Involvement over 3 Months

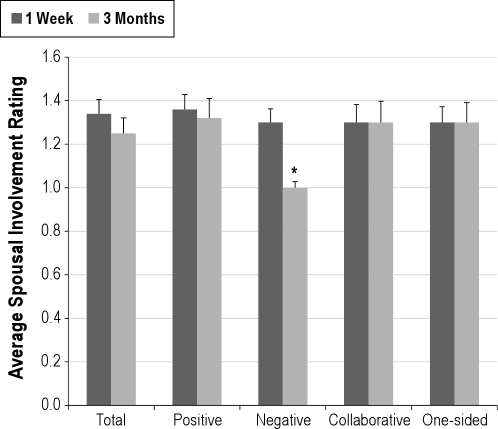

Average perceived spousal involvement scores total scores and subscores at 1 week and 3 months are presented in Figure 1. Average rating of within each subscore was low, in the range of less than 1-2 times per week. Perceived spousal involvement frequency at 3-month follow-up was only different for the negative subscore, which was lower at 3 months (p = 0.003). When perceived spousal involvement types were scored as either present or absent over the previous week, patients endorsed 5.75 items on the spousal involvement scale over the first week, and 4 items on the spousal involvement scale at 3-month follow-up (p = 0.07).

Figure 1.

Change in average spousal involvement from one week to three months (N = 16)

*p < 0. 01

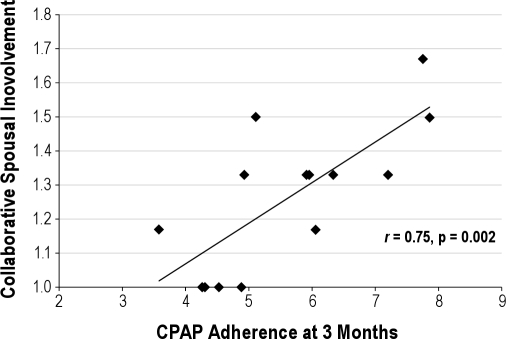

Associations Between Perceived Spousal Involvement and Adherence

Perceived collaborative spousal involvement was positively correlated with adherence at 3 months (r = 0.75, p = 0.002, Figure 2). Total spousal involvement scores, positive, negative, and one-sided involvement were not associated with adherence.

Figure 2.

Correlation between collaborative spousal involvement and adherence at three months (N = 14)

Associations Between Spousal Involvement, Ratings of Relationship Quality, and Interpersonal Behavior

There was a trend for an association between perceived collaborative spousal involvement and ratings of relationship support (r = 0.388, p = 0.07), but this score was not associated with relationship conflict. With respect to interpersonal support behaviors (Support Actions Scale-C, adapted to focus on CPAP use), perceived collaborative spousal involvement was positively correlated with the affiliation scale (r = 0.55, p = 0.03) and demonstrated a trend with the dominance scale (r = 0.47, p = 0.07). This suggests the interpersonal quality of collaborative spousal involvement is warm yet has some degree of control. Total perceived spousal involvement score and other subscales (positive, negative, and one-sided) were not associated with relationship support, conflict, or interpersonal ratings.

DISCUSSION

The goals of this study were to systematically evaluate spousal involvement in CPAP treatment and the effects of such involvement on adherence. We found that perceived spousal involvement was present in the majority of male OSA patients at low but consistent levels between 1 week and 3 months after initiation of CPAP therapy. Patients reported their spouse was involved in CPAP approximately 4-6 different ways occurring 1-2 times per week. Despite this low level, patients reported experiencing a variety of involvement types from their spouse. For example, the majority of patients reported positive and collaborative involvement, such as changing things at home to facilitate adherence. However, over half of the sample also reported their spouse used negative types of involvement at least once during the week, such as trying to evoke fear over the consequences of not using CPAP. We predicted that both the positive and collaborative involvement types would be associated with adherence. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that patients with higher perceptions of collaborative involvement in week 1 had higher CPAP adherence at 3-month follow-up. We did not find an association between those involvement types that were positive, (including collaborative and one-sided items), negative, or one-sided.

In addition to the spousal involvement measure, we also used a measure of interpersonal behavior to more precisely define the qualities of collaborative involvement. Results of this analysis demonstrated that collaborative spousal involvement is associated with the perception of warm and controlling interpersonal behaviors (e.g., helping in a friendly manner). Using an interpersonal framework allows for comparisons between our results with other previously reported studies of spousal interactions using different measures and in different populations, including measures of social support. In this case, we found that collaborative spousal involvement has similar interpersonal qualities as instrumental social support, which has been associated with adherence behaviors in other illnesses such as end stage renal disease and diabetes.34 The benefits of collaborative involvement appear to be two-fold. In addition to providing support and encouragement, collaborative involvement provides opportunities for spousal involvement problem solving, which can lead to better outcomes in problem solving tasks.35,36 Dealing with initial problems is a common occurrence in CPAP use, with up to two-thirds of CPAP users reporting initial problems with this treatment. These problems often require adjusting the equipment or learning strategies to get used to sleeping with the machine.37 Therefore, collaborative involvement from the spouse may provide both support and structure needed to overcome these initial problems in early CPAP use.

The longitudinal nature of our study allowed for evaluation of spousal involvement over several months. We found that most of the spousal involvement types remained consistent between 1 week and 3 months of CPAP treatment. The only type of spousal involvement that decreased was negative spousal involvement. One of the reasons this may have occurred is that negative spousal involvement may have been ineffective at motivating adherence or possibly caused annoyance or frustration. Previous studies have found that criticism tends to be unrelated to adherence or related to poorer adherence and emotional distress.26,38,39

Interpretation of results of our study are limited by a small sample size and attrition at 3-month follow-up. Furthermore, the high levels of adherence in our sample (average adherence > 5 hours) suggest there is a possibility of selection bias for those who entered the study and/or bias in the results due to attrition. Although not statistically significant, participants who dropped out of the study were less likely to share a bed every night, had higher AHIs and were less likely to have objective adherence reported. However, in notes from follow-up visits with a sleep medicine physician, there was no different between groups in whether the physician noted the patient self-reported having adequate or good adherence. In addition, the responses in this study are limited to the patient's report of the spouse's behavior. It is possible that patient observations may over or underestimate the frequency of spousal involvement. Indeed, one study of couples motivation and attitudes about health behaviors found spouse but not patient perceptions of spousal involvement to be related to behavior change efforts.30 Spousal involvement in CPAP adherence is likely an interaction between the patient and spouse's perception. Therefore, future research should consider the perspectives of both patient and spouse. Another consideration is that the findings of the current study are not necessarily generalizable to women with OSA. Due to significant gender differences in both the provision of and reactions to spousal involvement, it should not be assumed that results from male patients can be generalized to female patients.30,40–42

Future studies of spousal involvement should consider involving qualitative methods to gain more knowledge about the intricacies of spousal involvement in CPAP. The spousal involvement measure used in this study was developed in healthy couples discussing a range of health behaviors and did not take into account specific ways that spouses can be involved in CPAP usage (e.g., assisting with refilling the water reservoir or cleaning the machine). Many of the items administered in this study were rated with very low frequency. Not only could this have limited statistical power for the study due to restricted range, it may have not assessed potentially important behaviors because it was not developed with CPAP users. The measure also did not take into account individual differences in perceptions spousal involvement. For example, repeated reminders may be helpful for some patients and irritating to others. Therefore, investigation into both the specific types of involvement in CPAP treatment and also individual differences in perceptions of involvement should be taken into account in future research, particularly in the design of interventions.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the majority of married OSA male patients report that their spouse is involved in CPAP treatment in a variety of ways over the first three months of treatment. However, only collaborative spousal involvement was associated with higher adherence. Encouragement of collaborative involvement may lead to improvements in CPAP adherence through a blend of both support and structure for patients.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by an APA Division 38 Health Psychology graduate student research award, the University of Utah Sleep Wake Center, Grants 5K12 HD055884, and 1K23HL109110-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SR, White DP, Malhotra A, Stanchina ML, Ayas NT. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy for treating sleepiness in a diverse population with obstructive sleep apnea: results of a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:565–71. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Means MK, Lichstein KL, Edinger JD, et al. Changes in depressive symptoms after continuous positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2003;7:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s11325-003-0031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty LS, Kiely JL, Swan V, McNicholas WT. Long-term effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy on cardiovascular outcomes in sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2005;127:2076–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parish JM, Lyng PJ. Quality of life in bed partners of patients with obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 2003;124:942–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beninati W, Harris CD, Herold DL, Shepard JW., Jr The effect of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea on the sleep quality of bed partners. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:955–8. doi: 10.4065/74.10.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright RD. Sleeping together: A pilot study of the effects of shared sleeping on adherence to CPAP treatment in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:123–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doherty LS, Kiely JL, Lawless G, McNicholas WT. Impact of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy on the quality of life of bed partners of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2003;124:2209–14. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:173–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-119MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engleman HM, Wild MR, Weaver TE, et al. Improving CPAP use by patients with the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS) Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:81–99. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brin YS, Reuveni H, Greenberg S, Tal A, Tarasiuk A. Determinants affecting initiation of continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen S, Smith S, Oei TP, Douglas J. Cues to starting CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: development and validation of the cues to CPAP Use Questionnaire. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:229–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis KE, Seale L, Bartle IE, Watkins AJ, Ebden P. Early predictors of CPAP use for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2004;27:134–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron KG, Smith TW, Czajkowski LA, Gunn HE, Jones CR. Relationship quality and CPAP adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Behav Sleep Med. 2009;7:22–36. doi: 10.1080/15402000802577751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoy CJ, Vennelle M, Kingshott RN, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Can intensive support improve continuous positive airway pressure use in patients with the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1096–100. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9808008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis MA, Butterfield RM. Antecedents and reactions to health-related social control. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;13:416–27. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychol. 1999;18:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker JS, Anders SL. Social control of health behaviors in marriage. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2001;31:467–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umberson D. Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:907–17. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rook KS, Thuras PD, Lewis MA. Social control, health risk taking, and psychological distress among the elderly. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:327–34. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes M, Gove WR. Living alone, social integration, and mental health. Am J Sociol. 1981;87:48–74. doi: 10.1086/227419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krause N, Goldenhar L, Liang J, et al. Stress and exercise among the Japanese elderly. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:1429–41. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90385-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorpe CT, Lewis MA, Sterba KR. Reactions to health-related social control in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2008;31:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens MAP, Fekete EM, Franks MM, Rook KS, Druley JA, Greene K. Spouses' use of pressure and persuasion to promote osteoarthritis patients' medical adherence after orthopedic surgery. Health Psychol. 2009;28:48–55. doi: 10.1037/a0012385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baron KG, Smith TW, Berg CA, Czajkowski LA, Gunn H, Jones CR. Spousal involvement in CPAP adherence among patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2011;15:525–34. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:1028–39. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Solky-Butzel JA, Nagel LC. Assessing the quality of personal relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. 1997;14:339–56. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verhofstadt LL, Buysse A, Rosseel Y, Peene OJ. Confirming the three-factor structure of the Quality of Relationships Inventory Within Couples. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:15–21. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis MA, Butterfield RM, Darbes LA, Johnston-Brooks C. The conceptualization and assessment of health-related social control. J Soc Pers Relat. 2004;21:669–87. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterfield RM, Lewis MA. Health-related social influence: A social ecological perspective on tactic use. J Soc Pers Relat. 2002;19:505–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trobst KK. An interpersonal conceptualization and quantification of social support transactions. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2000;26:971–86. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiggins JS. A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1979;37:395–412. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:207–18. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meegan SP, Berg CA. Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. Int J Behav Dev. 2002;26:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg CA, Johnson MMS, Meegan SP, Strough J. Collaborative problem-solving interactions in young and old married couples. Discourse Process. 2003;35:33–58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engleman HM, Asgari-Jirhandeh N, McLeod AL, Ramsay CF, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Self-reported use of CPAP and benefits of CPAP therapy: a patient survey. Chest. 1996;109:1470–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helgeson VS, Novak SA, Lepore SJ, Eton DT. Spouse social control efforts: Relations to health behavior and well-being among men with prostate cancer. J Soc Pers Relat. 2004;21:53–86. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fekete EM, Stephens MA, Druley JA, Greene KA. Effects of spousal control and support on older adults' recovery from knee surgery. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:302–10. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westmaas JL, Wild TC, Ferrence R. Effects of gender in social control of smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2002;21:368–76. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tucker JS, Orlando M, Elliott MN, Klein DJ. Affective and behavioral responses to health-related social control. Health Psychol. 2006;25:715–22. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]