Abstract

The increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) during neuronal activation can be only partially attenuated by individual inhibitors of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), cyclooxgenase-2, group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, or adenosine receptors. Some studies that used a high concentration (500 μM) of the cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor SC-560 have implicated cyclooxygenase-1 in gliovascular coupling in certain model systems in the mouse. Here, we found that increasing the concentration of SC-560 from 25 μM to 500 μM over whisker barrel cortex in anesthetized rats attenuated the CBF response to whisker stimulation. However, exogenous prostaglandin E2 restored the response in the presence of 500 μM SC-560 but not in the presence of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, thereby suggesting a limited permissive role for cyclooxygenase-1. Furthermore, inhibition of the CBF response to whisker stimulation by an EET antagonist persisted in the presence of SC-560 or a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, thereby indicating that the EET-dependent component of vasodilation did not require cyclooxygenase-1 or -2 activity. With combined inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2, mGluR, nNOS, EETs, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and adenosine 2B receptors, the CBF response was reduced by 60%. We postulated that the inability to completely block the CBF response was due to tissue acidosis resulting from impaired clearance of metabolically produced CO2. We tested this idea by increasing the concentration of superfused bicarbonate from 25 to 60 mM and found a markedly reduced CBF response to hypercapnia. However, increasing bicarbonate had no effect on the initial or steady-state CBF response to whisker stimulation with or without combined inhibition. We conclude that the residual response after inhibition of several known vasodilatory mechanisms is not due to acidosis arising from impaired CO2 clearance when the CBF response is reduced. An unidentified mechanism apparently is responsible for the rapid, residual cortical vasodilation during vibrissal stimulation.

Keywords: acidosis, metabotropic glutamate receptor, neurovascular unit, prostaglandin E2, whisker barrel cortex

multiple pathways have been implicated in coupling cerebral blood flow (CBF) to changes in neuronal activity (15). These include N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (18, 29), neuronal nitric oxide (NO) synthase (nNOS) (6), astrocyte metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) (18, 33, 39), epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (18, 30, 31, 33), potassium channels (7, 11), adenosine (6, 28), cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) (35, 39), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (2, 18, 23, 26, 34). However, questions remain about how these pathways are integrated and whether they account for all of the coupling mechanisms. Combinations of pharmacological inhibitors of multiple pathways generally do not produce additive effects in reducing the increase in CBF during neuronal activation and do not completely eliminate the response. For example, individual administration of inhibitors of mGluR, EETs, potassium channels, and adenosine receptors partially suppresses the vasodilatory response, whereas combined administration produces little additional suppression (28, 33). These observations are consistent with a sequential gliovascular signaling concept in which glutamate release during activation acts on astrocytic mGluR to stimulate release of ATP, which is subsequently hydrolyzed extracellularly to adenosine (37), and to stimulate release of EETs (1, 25), which can promote opening of potassium channels in astrocytes (10) and vascular smooth muscle (13) to produce vasodilation. Likewise, combining NOS inhibitors with adenosine (6) or EET (31) inhibitors or combining a NMDA receptor antagonist with an EET inhibitor (18) does not produce additive suppression of the CBF response or complete blockade of the response. Moreover, restoration of the CBF response after NOS inhibition by an NO donor suggests that NO acts in a permissive fashion (20), possibly by inhibiting synthesis of the vasoconstrictor 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and thereby permitting vasodilation by other pathways (21).

Less work has been reported on the interaction of COX pathways with other signaling mechanisms. The nonspecific COX inhibitor indomethacin has been shown to individually inhibit the CBF response to activation (18) but not to completely block the response when combined with inhibitors of NOS, EETs, adenosine, and inward rectifier potassium channels (19). In the presence of indomethacin, a synthesis inhibitor of EET is still capable of reducing the CBF response to whisker stimulation (30). However, the interaction of COX with other pathways has not been well studied with the use of selective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors. A recent study reported no additive suppression of the CBF response to whisker stimulation with combined COX-2 and NMDA receptor inhibitors (18). Furthermore, whether a COX-1 or COX-2 metabolite mediates the CBF response or acts in a permissive fashion analogous to the role of NO has not been clearly discerned. Here, we examined whether an antagonist of EET was capable of reducing the CBF response in the presence of a selective COX-1 or COX-2 inhibitor. To investigate whether a COX-1 or COX-2 metabolite such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) acts in a permissive fashion, exogenous PGE2 was administered in the presence of a selective COX-1 or COX-2 inhibitor. PGE2 was chosen because it can be released from astrocytes in response to glutamate (40). Whereas several studies have shown that COX-2 inhibitors decrease the CBF response to activation (2, 18, 23, 26, 34), some controversy persists on the role of COX-1. Studies using concentrations of 25–100 μM of the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 [5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazole] failed to reduce the CBF response to whisker stimulation in the mouse (27) or the rat (18) or to a mGluR agonist in the rat (22), whereas concentrations of 500 μM reduced vasodilation to photolysis of caged Ca2+ in astrocytes in vivo in mice (35) and to odorant stimulation in olfactory bulb glomeruli in mice (32). Thus, in the present study, we also examined the effects of SC-560 in both rats and mice and determined whether increasing the concentration to 500 μM would reveal an inhibitory effect on the CBF response to whisker stimulation.

Because the combination of COX inhibitors with other pathway inhibitors failed to completely block the CBF response, other unidentified mechanisms of neurovascular coupling may exist. One explanation for the incomplete block of the CBF response is a mismatch between metabolically produced CO2 and clearance of CO2 by CBF. Thus, when feed-forward signaling mechanisms from neurons and astrocytes are blocked, additional metabolic feedback mechanisms may be recruited. Ordinarily, the increase in CBF during neuronal activation is proportional to an increase in glucose consumption (8), which, in turn, would be expected to generate a proportional increase in CO2 production. Thus proportional increases in CBF and CO2 production normally would be expected to result in little change in tissue Pco2. However, if inhibitors of vasodilation during neurovascular coupling do not reduce the glucose consumption response, then carbonic acidosis may develop and, because CO2 is a potent cerebral vasodilator, produce a residual CBF response to neuronal activation. Because vasodilation in response to increases in CO2 is known to be inversely related to the extracellular concentration of bicarbonate ions (16, 17), one strategy to address the role of CO2 is to manipulate the extracellular [HCO3−]. Thus increasing extracellular [HCO3−] would be expected to reduce the CBF response to neuronal activation if the response depends on an increase in tissue Pco2.

Five main hypotheses were tested in the present study. First, increasing the concentration of the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 from 25 μM to 500 μM produces a significant reduction of the CBF response to whisker stimulation in rat and mouse. Second, administration of the EETs antagonist 14,15-EEZE [14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid] produces additional inhibition of the CBF response to whisker stimulation in rats in the presence of the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 or the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 [N-[2-(cyclohexyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-methanesulfonamide]. Third, reductions of the CBF response to whisker stimulation by the COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor in rats can be reversed by concurrent administration of PGE2. Fourth, increasing extracellular [HCO3−] has no significant effect on the CBF response to whisker stimulation under control conditions when feed-forward signaling mechanisms are intact. Fifth, when COX inhibitors are combined with inhibitors of other known feed-forward pathways, increasing extracellular [HCO3−] now blocks the residual CBF response to whisker stimulation.

METHODS

All procedures on animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Johns Hopkins University and were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Studies were performed on male Wistar rats weighing 250–350 g (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) and on male C57Bl/6 mice weighing 22–28 g (Charles River, Wilmington, MA).

Procedures on rats.

Rats were initially anesthetized with ∼5% isoflurane and mechanically ventilated through a tracheostomy with 2.0% isoflurane and ∼30% O2. As described previously (21, 33), a femoral artery and femoral vein were catheterized, rectal temperature was maintained at ∼37°C, and a portion of the skull overlying the left whisker barrel cortex was thinned to translucency with a drill for placement of a laser-Doppler flow (LDF) probe (Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden) 2 to 3 mm posterior and 7 mm lateral from bregma. To administer drugs locally over the surface of the cerebral cortex, a small drill hole was made superior to the LDF recording site, and a catheter with its tip tapered to ∼120 μm was gently inserted subdurally at ∼3 mm from the recording site. Drainage of superfused fluid occurred passively from a second small hole 2 to 3 mm inferior to the flow probe site. The subarachnoid space was superfused at a rate of 5 μl/min with warmed, artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing (in mM) 156 Na+, 3 K+, 1.25 Ca2+, 0.66 Mg2+, 133 Cl−, 25 HCO3−, 6.7 urea, and 3.7 dextrose. When the surgery was complete, 33 mg/kg of α-chloralose was injected intraperitoneally. Isoflurane was discontinued 20 min later, and the rats remained sedated with a continuous intravenous infusion of 12 mg·kg−1·h−1 of α-chloralose.

The whiskers on the right side were inserted through a screen mesh that was connected to a solenoid-driven piston that mechanically displaced them in an anterior-posterior direction at 10 Hz (21). Recordings of LDF were made over a 60-s baseline period, 60-s of whisker displacement, and 30-s of recovery. Measurements were averaged from three trials spaced 2 to 3 min apart. The experimental design consisted of making a set of control measurements of mean arterial blood pressure, arterial blood gases, and triplicate LDF responses to whisker stimulation at least 1 h after commencing superfusion with artificial CSF. A second set of measurements was made after 1-h treatment with drugs, and a third set of measurements was repeated after another 1-h treatment with an additional drug. This design allowed for paired comparisons of responses within the same animal. Previous work indicated that the responses were reproducible over a 3-h period with this procedure (21, 30, 33).

The concentration of drugs added to the superfusate was based on literature showing efficacy in the cerebral circulation in vivo. The COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 was superfused at a concentration of 25 μM, which was shown to maximally inhibit the LDF response to bradykinin and hypercapnia (27), and at a concentration of 500 μM, which was shown to inhibit arteriolar dilation to elevated astrocyte Ca2+ (35). PGE2 was superfused at a concentration of 5 μM, which was found in preliminary experiments to nearly restore baseline LDF after treatment with 500 μM of SC-560. The COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 was superfused at a concentration of 100 μM, which was shown to maximally inhibit the LDF response to whisker stimulation (26). The EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE was superfused at a concentration of 30 μM, which was found previously to inhibit the LDF response to whisker stimulation (33). To inhibit mGluR, the group I mGluR subtype 1 antagonist (S)-(+)-α-amino-4-carboxy-2-methylbenzeneacetic acid (LY-367385; 300 μM) and the subtype 5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP; 100 μM) were superfused together. This drug combination attenuates the LDF response to whisker stimulation (39), and these doses completely block the increase in LDF in response to an mGluR agonist (22). The adenosine A2B antagonist MRS-1754 was superfused at concentration of 1 μM, which was found previously to attenuate the LDF response to whisker stimulation (33). An A2A antagonist was not used because two different A2A antagonists were found to have no effect on the LDF response in this model (33). The NMDA antagonist MK-801 was superfused at a concentration of 10 μM, which was reported to blunt the LDF response to whisker stimulation (18, 29). To inhibit nNOS, 7-nitroindazole (7-NI) was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 40 mg/kg 1 h before the response to whisker stimulation was tested. This dose produces stable reductions in the LDF response to whisker stimulation for at least 2 h (21).

To test the role of carbonic acidosis in the LDF response to whisker stimulation, we increased the [HCO3−] in the superfused artificial CSF from 25 to 60 mM. The artificial CSF was bubbled with CO2 to produce a partial pressure of CO2 (Pco2) of ∼40 Torr, which resulted in a pH of ∼7.33 at 25 mM [HCO3−] and ∼7.73 at 60 mM [HCO3−]. The [Cl−] was decreased from 133 mM to 98 mM to maintain the osmolarity of the solution. The LDF response to whisker stimulation was measured 1 h after increasing [HCO3−]. Increasing [HCO3−] in the CSF perfusate has been shown to reduce the blood flow response to hypercapnia in dogs (16). To demonstrate that 1 h of cortical superfusion with artificial CSF containing 60 mM HCO3− could reduce the LDF response in the present model in rats, we tested the LDF response to hypercapnia after superfusion with CSF containing 25 mM HCO3− for 1 h and again after superfusion with CSF containing 60 mM HCO3− for 1 h at a rate of 5 μl/min in a separate set of rats. Hypercapnia was produced by ventilation with 7% CO2 for 10 min at each [HCO3−], and the change in LDF was averaged over the last 3 min.

Procedures in mice.

Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane and maintained with 2% isoflurane. The lungs were mechanically ventilated with ∼30% O2 via a tracheostomy, the femoral artery was catheterized to monitor arterial pressure, and rectal temperature was maintained at ∼37°C. A catheter was inserted into the peritoneal cavity, and urethane was administered (500 mg/kg plus 250 mg·kg−1·h−1). The inspired concentration of isoflurane was reduced to 1%. A closed cranial window was constructed over the whisker barrel cortex, and an LDF probe was placed over the window as described previously (21). Isoflurane was discontinued, and warmed artificial CSF was perfused through the window at a rate of 100 μl/min. Control LDF responses to three 60-s periods of whisker stimulation were measured at ∼90 min after completing the surgery and discontinuing isoflurane. The window was then superfused with 500 μM SC-560 or 100 μM NS-398. At 1 h of superfusion with these agents, the LDF response to three epochs of whisker stimulation was measured again.

Statistical analysis.

The LDF was averaged over the 60-s period of whisker stimulation and expressed as percent change from the preceding 60-s baseline. The percent responses at each hour were compared within the same group of animals by repeated-measures ANOVA. If an overall significant effect was present, the individual responses were compared at each time by the Newman-Keuls multiple range test. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Arterial Pco2 and mean arterial blood pressure were in the normal physiological range and remained stable over the 3-h course of LDF measurements in all groups of rats (Table 1). Arterial Po2 was maintained in the approximate range of 100–120 Torr, arterial pH was maintained in the approximate range of 7.35–7.42, and arterial hemoglobin concentration was unchanged in the range of 11–13 g/dl.

Table 1.

Arterial Pco2, arterial blood pressure, and baseline laser-Doppler flow before stimulation in rats

| Hours of Treatment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Pco2, Torr | |||

| 25 μM SC-560/14,15-EEZE | 39 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 |

| 500 μM SC-560/14,15-EEZE | 39 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 |

| 500 μM SC-560/PGE2 | 38 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 |

| NS-398/14,15-EEZE | 38 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 |

| NS-398/PGE2 | 39 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

| 60 mM HCO3−/14,15-EEZE | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 |

| MPEP + LY-367385/60 mM HCO3− | 39 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

| MPEP + LY-367385 + 7-NI + NS-398/60 mM HCO3− | 38 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

| Cocktail /60 mM HCO3− | 38 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| 25 μM SC-560/14,15-EEZE | 93 ± 3 | 93 ± 3 | 93 ± 4 |

| 500 μM SC-560/14,15-EEZE | 95 ± 5 | 95 ± 5 | 95 ± 4 |

| 500 μM SC-560/PGE2 | 101 ± 3 | 101 ± 2 | 101 ± 2 |

| NS-398/14,15-EEZE | 101 ± 4 | 101 ± 4 | 101 ± 4 |

| NS-398/PGE2 | 109 ± 4 | 110 ± 4 | 108 ± 3 |

| 60 mM HCO3−/14,15-EEZE | 103 ± 3 | 104 ± 3 | 104 ± 3 |

| MPEP + LY-367385/60 mM HCO3− | 99 ± 4 | 100 ± 4 | 100 ± 3 |

| MPEP + LY-367385 + 7-NI + NS-398/60 mM HCO3− | 94 ± 2 | 93 ± 2 | 94 ± 2 |

| Cocktail /60 mM HCO3− | 112 ± 7 | 112 ± 7 | 112 ± 8 |

| Baseline laser-Doppler flow, % of 1-h baseline | |||

| 25 μM SC-560/14,15-EEZE | 85 ± 4* | 85 ± 4* | |

| 500 μM SC-560/14,15-EEZE | 82 ± 2* | 82 ± 2* | |

| 500 μM SC-560/PGE2 | 85 ± 4* | 93 ± 2*† | |

| NS-398/14,15-EEZE | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 | |

| NS-398/PGE2 | 100 ± 1 | 100 ± 2 | |

| 60 mM HCO3−/14,15-EEZE | 77 ± 5* | 70 ± 4*† | |

| MPEP + LY-367385/60 mM HCO3− | 100 ± 1 | 92 ± 3*† | |

| MPEP + LY-367385 + 7-NI + NS-398/60 mM HCO3− | 90 ± 1* | 90 ± 1* | |

| Cocktail /60 mM HCO3− | 79 ± 3* | 69 ± 3*† | |

Values are means ± SE. Groups are defined by 2-h treatment/3-h treatment. MPEP, 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine; 7-NI, 7-nitroindazole.

P < 0.05 from 1 h;

P < 0.05 from 2 h.

Whisker stimulation in rats produced a brisk increase in LDF over the whisker barrel cortex. After 60 s of stimulation, LDF rapidly returned to baseline (Fig. 1). Superfusion of the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 at a concentration of 25 μM for 1 h decreased the baseline LDF (Table 1) but had no effect on the steady-state response to whisker stimulation when expressed as a percentage of the new baseline (Fig. 1). Addition of the EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE in the presence of SC-560 did not produce a further change in the baseline LDF but attenuated the steady-state response to whisker stimulation. The onset of the LDF response remained rapid in the presence of SC-560 alone or in combination with 14,15-EEZE.

Fig. 1.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), 25 μM SC-560, or 25 μM SC-560 + 30 μM 14,15-EEZE (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; †P < 0.05 from SC-560 value; n = 6.

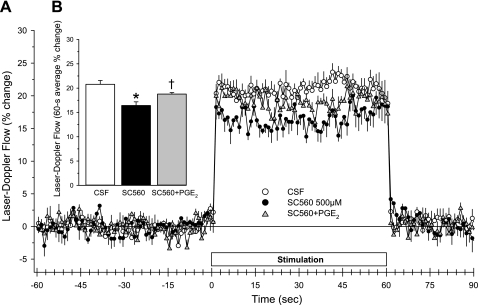

In another set of rats, the concentration of superfused SC-560 was increased to 500 μM. The onset of the LDF response over the first 3 s of whisker stimulation remained unaffected (Fig. 2). With continued stimulation, the LDF response slightly subsided. The response averaged over the 60-s stimulation period was significantly reduced. Addition of 14,15-EEZE in the presence of the high concentration of SC-560 further reduced the steady-state response. Thus the EET-dependent component of vasodilation did not require COX-1 activity.

Fig. 2.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF, 500 μM SC-560, or 500 μM SC-560 + 30 μM 14,15-EEZE (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; †P < 0.05 from SC-560 value; n = 6.

One possible explanation for the attenuated LDF response to the high concentration is that the full LDF response requires a minimal level of a vasodilatory metabolite, such as PGE2. To test this possibility, we superfused 5 μM PGE2 concurrently with 500 μM SC-560. In this set of rats, superfusion of SC-560 alone decreased baseline LDF (Table 1) and attenuated the increase in LDF during whisker stimulation (Fig. 3). Concurrent superfusion of PGE2 and SC-560 increased baseline LDF and increased the response to whisker stimulation compared with SC-560 alone. Moreover, the response was no longer significantly different from the control response.

Fig. 3.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF, 500 μM SC-560, or 500 μM SC-560 + 5 μM PGE2 (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; †P < 0.05 from SC-560 value; n = 6.

To evaluate whether EET-dependent dilation required COX-2 activity, we tested the effect of the EET antagonist in the presence of the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 in another set of rats. Superfusion of 100 μM NS-398 did not affect baseline LDF (Table 1) but significantly reduced the LDF response to whisker stimulation (Fig. 4A). Addition of 14,15-EEZE in the presence of NS-398 did not change baseline LDF but further reduced the LDF response to whisker stimulation.

Fig. 4.

Cortical laser-Doppler flow (LDF; ±SE) of rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, averaged over 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with artificial CSF, 100 μM NS-398, or 100 μM NS-398 + 30 μM 14,15-EEZE (n = 8; A) or with vehicle in artificial CSF, 100 μM NS-398, or 100 μM NS-398 + 5 μM PGE2 (n = 6; B). Percent change in LDF of mice during 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with artificial CSF or 500 μM SC-560 (n = 10; C) is shown. Percent change in LDF of mice during 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with artificial CSF or 100 μM NS-398 (n = 4; D) is shown. *P < 0.05 from control value; †P < 0.05 from NS-398 value.

To test whether a minimal amount of PGE2 is required for the LDF response to whisker stimulation in the presence of the COX-2 inhibitor, 5 μM PGE2 was superfused concurrently with 100 μM NS-398 in another set of rats. As in the previous set of rats, superfusion of NS-398 alone did not affect baseline LDF (Table 1) but significantly reduced the LDF response to whisker stimulation (Fig. 4B). However, in contrast with the effect of combining PGE2 with SC-560, combining PGE2 with NS-398 did not increase the LDF response to whisker stimulation.

In mice, SC-560 at a concentration of 500 μM has been shown to reduce arteriolar dilation to elevated Ca2+ (35), whereas SC-560 at a concentration of 25 μM had no effect on the LDF response to whisker stimulation (27). To test whether the higher concentration of SC-560 would more effectively inhibit the LDF response to whisker stimulation in mice, we superfused SC-560 over the cortical surface of mice at a concentration of 500 μM. The LDF response to 60 s of whisker stimulation was unchanged from the control response (Fig. 4C). In agreement with others (26), superfusion of 100 μM NS-398 in another set of mice was effective at reducing the LDF response to whisker stimulation (Fig. 4D).

None of the agents used in this study or combinations of other agents tested in previous studies (6, 11, 19, 31, 33) completely blocked the CBF response to activation. We speculated that the impaired CBF response might produce carbonic acidosis as a result of inadequate CO2 clearance. To test whether the residual response was related to enhanced carbonic acidosis, we increased the extracellular [HCO3−] to buffer any increase in CO2. Increasing [HCO3−] from 25 to 60 mM in the artificial CSF perfusate for 1 h in rats markedly reduced the LDF response to hypercapnia (Fig. 5). Thus the 1-h period of superfusion was sufficient for the increased [HCO3−] to permeate into the underlying tissue subtended by the LDF probe and to blunt the vascular response to carbonic acidosis.

Fig. 5.

Arterial partial pressure of CO2 (Pco2; ±SE) in rats during normocapnia and hypercapnia after 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF containing normal [HCO3−] (25 mM) or elevated [HCO3−] (60 mM) (A). Percent change in LDF during hypercapnia (B) is shown. *P < 0.05 from 25 mM HCO3− value; n = 5.

As expected, increasing [HCO3−] in the CSF perfusate to 60 mM for 1 h decreased baseline LDF (Table 1). However, the increased [HCO3−] alone had no effect on the LDF response to whisker stimulation from the new baseline (Fig. 6). Addition of 14,15-EEZE to the perfusate for an additional hour with elevated [HCO3−] resulted in an attenuation, but not a complete block, of the LDF response to whisker stimulation. Thus the EET antagonist is still capable of inhibiting the LDF response in the presence of elevated [HCO3−], but a significant response persists.

Fig. 6.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF containing normal [HCO3−] (25 mM), elevated [HCO3−] (60 mM), or 60 mM HCO3− + 30 μM 14,15-EEZE (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; †P < 0.05 from 60 mM HCO3− value; n = 8.

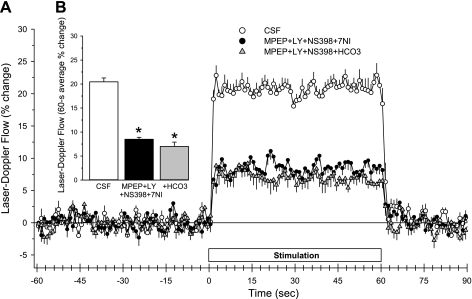

Some studies have shown that inhibition of mGluRs can attenuate but not abolish the LDF response to whisker stimulation (33, 39). Here, we first superfused the mGluR antagonists MPEP plus LY-367385 to attenuate the response and then increased the [HCO3−] of the superfusate to determine whether the residual response could be further attenuated. Superfusion of MPEP plus LY-367385 with normal [HCO3−] for 1 h did not change baseline LDF (Table 1), but it attenuated the steady response to whisker stimulation without delaying the response (Fig. 7). Increasing the [HCO3−] to 60 mM during an additional hour of MPEP plus LY-367385 superfusion produced no additional decrement in the response.

Fig. 7.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF containing normal [HCO3−] (25 mM), 100 μM 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) + 300 μM LY-367385, or 100 μM MPEP + 300 μM LY-367385 + 60 mM HCO3− (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; n = 7.

The effect of combined inhibition of the mGluR pathway and the COX-2 and nNOS pathways was then evaluated. Administration of MPEP, LY-367385, and NS-398 in the CSF superfusate and administration of 7-NI intraperitoneally decreased baseline LDF (Table 1) and markedly reduced the LDF response to whisker stimulation (Fig. 8). Increasing the superfusate [HCO3−] to 60 mM did not significantly reduce the response further compared with that at the normal [HCO3−]. The on-response and off-response remained rapid in the presence of the combined inhibitors at elevated [HCO3−].

Fig. 8.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF containing normal [HCO3−] (25 mM), 1 h of superfusion with 100 μM MPEP + 300 μM LY-367385 + 100 μM NS-398 and intraperitoneal administration of 7-nitroindazole (7-NI; 40 mg/kg), or 1 h of superfusion with 100 μM MPEP + 300 μM LY-367385 + 100 μM NS-398 + 60 mM HCO3− (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; n = 7.

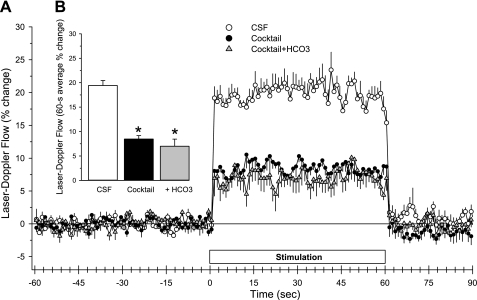

Other pathways implicated in the neurovascular coupling response include adenosine A2B receptors (33) and NMDA receptors (18, 29). In an attempt to further reduce the LDF response, the adenosine A2B receptor antagonist MRS-1754, the NMDA antagonist MK-801, the EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE, and the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 (500 μM) were added with MPEP, LY-367385, and NS-398 for combined CSF superfusion for 1 h. In addition, 7-NI was administered intraperitoneally. This cocktail of eight drugs decreased baseline LDF (Table 1) and markedly inhibited the LDF response to whisker stimulation (Fig. 9). However, a residual response persisted. When the CSF [HCO3−] was then increased to 60 mM in the presence of the drug cocktail, baseline LDF was decreased further, but the LDF response to whisker stimulation was not decreased further. Again, the residual on-response and off-response remained rapid in the presence of the drug cocktail at elevated [HCO3−].

Fig. 9.

Time course of cortical laser-Doppler flow (±SE) in rats, expressed as percent change from a 60-s baseline recording, during and after 60 s of whisker stimulation at 1 h of subarachnoid superfusion with CSF containing normal [HCO3−] (25 mM), 1 h of superfusion with drug cocktail (100 μM MPEP + 300 μM LY-367385 + 30 μM 14,15-EEZE, 500 μM SC-560, 100 μM NS-398, 1 μM MRS-1754, 10 μM MK-801, and intraperitoneal administration of 40 mg/kg 7-nitroindazole), or 1 h of superfusion with drug cocktail + 60 mM HCO3− (A). Inset bar graph shows the percent change in flow during whisker stimulation averaged over the 60-s stimulation period (B). *P < 0.05 from CSF value; n = 6.

DISCUSSION

This study presents several major findings. First, increasing the concentration of the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 from 25 to 500 μM in rats moderately reduces the steady state cortical blood flow response to whisker stimulation in rats, but adding exogenous PGE2 to increase baseline blood flow also restores the response, thereby suggesting a permissive role of COX-1 in rats. An obligatory role of a COX-1 metabolite was not apparent in mice. Second, the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 effectively attenuates the blood flow response in both rats and mice, but exogenous PGE2 does not restore the response in rats, thereby suggesting that COX-2 plays more of a mediatory role. Third, the EET antagonist reduces the blood flow response after either COX-1 or COX-2 inhibition, thereby indicating an independent effect of EETs. Fourth, elevating extracellular [HCO3−] to a level that inhibits hypercapnic vasodilation does not attenuate the blood flow response to whisker stimulation under control conditions. Fifth, elevating extracellular [HCO3−] does not result in further attenuation of the blood flow response to whisker stimulation after inhibition of mGluR, after combined inhibition of mGluR, COX-2, and nNOS, or after combined inhibition of mGluR, COX-2, nNOS, COX-1, EETs, NMDA receptors, and adenosine A2B receptors. Thus carbonic acidosis is not a major contributor to the residual response after inhibition of several known signaling pathways for neurovascular coupling in rodent whisker barrel cortex.

The present results with whisker stimulation confirm the findings of others in mice and rats that COX-2 inhibitors have a greater effect than COX-1 inhibitors on the CBF response to activation in whisker barrel cortex (18, 26, 27). Inhibitors of COX-2 have also been shown to attenuate the CBF response in forelimb and hind limb cortex after peripheral electrical stimulation in rats (2, 23, 34). Thus COX-2 is the predominant isoform contributing to functional hyperemia in various regions of primary sensory cortex in both rodent species. The present studies extend these findings by demonstrating that the EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE significantly attenuates the CBF response to whisker stimulation in the presence of a COX-1 or COX-2 inhibitor. These results imply that COX metabolism of 5,6-EET, which is the only EET regioisomer that can be metabolized by COX, does not account for all of the EET-dependent vasodilation during neuronal activation. This conclusion is also consistent with previous work showing that an EET synthesis inhibitor was capable of reducing the CBF response to whisker stimulation in the presence of the non-isoform-specific COX inhibitor indomethacin (30). Furthermore, the current findings with whisker stimulation are congruent with recent work showing that superfusion of a group I mGluR agonist in vivo evoked an increase in CBF that was largely dependent on EETs, moderately dependent on COX-2 activity, and not significantly dependent on COX-1 activity (22).

Astrocytes in mouse cortex and rat hippocampus are reported to express COX-1 (12, 35), whereas astrocytes in mouse and rat cortex are reported to have little or undetectable constitutive expression of COX-2 (18, 35). Cultured astrocytes release PGE2 in response to external glutamate (40), and aspirin inhibits arteriolar dilation evoked by astrocyte activation in brain slices (39). Thus it has been assumed that a COX-1 metabolite mediates the dilation that occurs in response to astrocyte activation. In support of this concept, the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 has been shown to inhibit arteriolar dilation in vivo to increased astrocyte Ca2+ in mouse cerebral cortex (35) and to sensory activation in olfactory glomeruli (32) and cochlear sensory organs (5). However, the concentration of SC-560 that was locally applied in those studies was 500 μM. In the present study, we showed that increasing the concentration of superfused SC-560 from 25 μM, which was shown previously to produce maximal inhibition of the vasodilation evoked by bradykinin (27), to 500 μM produced a small decrement in the steady-state CBF response to whisker stimulation in the rat, although no significant effect was detected in mice. However, adding exogenous PGE2 to the superfusate at a concentration that increased baseline CBF resulted in a restoration of the CBF response to whisker stimulation. This result suggests that a COX-1 metabolite permits full expression of the steady-state hyperemic response but that a COX-1 metabolite does not necessarily mediate the response. This metabolite may be PGE2, PGI2, or other prostanoid dilators released from cells comprising the neurovascular unit.

Superfusion of 25 μM SC-560 decreased baseline LDF by 15 ± 4% but had no effect on the LDF response to whisker stimulation, whereas superfusion of 500 μM SC-560 decreased baseline LDF by 18 ± 2% but significantly reduced the response to whisker stimulation. Thus SC-560 exerts a differential sensitivity on baseline flow and activated flow. Although the difference between the 15% and 18% reduction in baseline LDF is small and not statistically different, inhibition of COX-1 at the 25 μM concentration may be submaximal. In isolated cochleae superfused with SC-560, increasing the concentration from 10 μM to 1,000 μM was found to produce nearly an additional 20% inhibition of COX activity (5). Thus inhibition of COX-1 may need to be nearly 100% to reveal this permissive effect of COX-1 to the neurovascular response in cerebral cortex of rat, whereas a significant decrease in tonic release of a COX-1 metabolite may require much less COX-1 inhibition. However, this permissive effect may not be present in all species since the high concentration of SC-560 had no effect on the LDF response to whisker stimulation in the mouse.

An alternative explanation for the 500 μM effect on the evoked LDF response is that the high concentration of SC-560 is also inhibiting COX-2 or other enzymes (3). However, if the reduction of the LDF response to whisker stimulation in the rat was simply due to inhibition of COX-2 by SC-560, then the addition of exogenous PGE2 might be expected to exert no effect on the activation response, as was the case with NS-398. The different effects of exogenous PGE2 in the presence of NS-398 versus the high concentration of SC-560 argues against a common target.

Because 14,15-EEZE superfusion in the presence of NS-398 produced additional inhibition of the CBF response, the epoxygenase and COX-2 signaling pathways are at least partly independent of each other. However, the CBF response was not completely blocked by combined inhibitors. The literature indicates that other combinations of inhibitors also failed to block the vascular response completely. These combinations included inhibitors of NOS + adenosine receptors (6, 33), NOS + EETs (21, 31), EETs + adenosine receptors (33), NOS + adenosine receptors + EETs (19), NOS + adenosine receptors + EETs + inward-rectifier K+ (Kir) channels (19), Kir channels + calcium-activated K+ (KCa) channels (11), mGluR + adenosine receptors (33), mGluR + EETs (33), and mGluR + adenosine receptors + EETs (33), NMDA receptors + COX-2 (18), and NMDA receptors + EETs (18). One simple explanation for the inability of inhibitors of known signaling pathways in neurovascular coupling to completely eliminate the increase in CBF during neuronal activation is that metabolically based signals are recruited as a result of a mismatch between blood flow and metabolic demand when feed-forward signals from neurons and astrocytes are blocked.

We considered the possibility that an increase in tissue Pco2 would occur when the increase in blood flow was impaired by inhibitors of these feed-forward signaling pathways. An increase in Pco2 produces cerebral vasodilation by decreasing extracellular pH. Increasing extracellular [HCO3−] will attenuate the change in extracellular pH for a given change in tissue Pco2. Indeed, we found that increasing the CSF superfusate [HCO3−] from 25 to 60 mM markedly attenuated the increase in LDF to an increase in arterial Pco2. This finding is in agreement with earlier studies showing that increasing the CSF [HCO3−] to 60 mM reduces pial arterial dilation (17) and the increase in CBF during hypercapnia (16). Moreover, this result indicated that the increase in [HCO3−] was able to permeate sufficiently into the tissue sampled by the LDF probe. The decrease in baseline LDF after 1 h of superfusion with elevated [HCO3−] also indicates the efficacy of permeation into the cortical tissue.

Whisker stimulation in the presence of increased extracellular [HCO3−] produced the same percent increase in LDF from the new baseline LDF as that occurring with normal extracellular [HCO3−]. Our interpretation of this finding is that tissue Pco2 does not normally change significantly during neuronal activation. This interpretation is consistent with the lack of a large change in tissue pH arising from lactate accumulation (36). However, the umbelliferone indicator technique used to measure tissue pH on cryostat sections of cortex after whisker stimulation in this study does not strictly control for postmortem changes in tissue Pco2.

When group I mGluR antagonists were used to attenuate the LDF response to whisker stimulation, elevation of extracellular [HCO3−] did not result in further attenuation of the LDF response to whisker stimulation. Thus inhibiting mGluR resulted in a residual LDF response that was not primarily attributable to tissue carbonic acidosis. Partial inhibition of the LDF response to cortical activation by mGluR antagonists is consistent with several reports in the literature (18, 33, 39). However, a recent study using 5 s of whisker stimulation did not show an inhibition of the flow response (4). Our results are not necessarily in conflict with this observation in that the rise time of the response over the first few seconds of stimulation was unabated. Thus mGluR may be more important for sustaining the CBF response to cortical activation. Although this same study failed to see an effect of the mGluR antagonists on the flow response to 24 s of whisker stimulation, the control flow response without antagonists spontaneously declined between 5 and 24 s. No such decline was evident in our study with 60 s of whisker stimulation. Perhaps differences in the methods of mechanical whisker stimulation may influence the contribution of mGluR to the steady-state flow response.

COX-2 and nNOS represent two other major signaling pathways that contribute to neurovascular coupling. When inhibitors of these two pathways were combined with group I mGluR antagonists, the LDF response to whisker stimulation was inhibited by 60%. However, the residual LDF response was unaffected by elevation of extracellular [HCO3−]. By the addition of the inhibitors of EETs, COX-1, NMDA receptors, and adenosine A2B receptors to the cocktail, the LDF response was not further suppressed and increasing extracellular [HCO3−] did not substantially reduce the remaining 40% response. Thus carbonic acidosis is not responsible for the residual LDF response to whisker stimulation when several known signaling pathways are blocked.

It should be noted that we did not include inhibitors of KCa and Kir channels in the drug cocktail. Kir activation on vascular smooth muscle depends on astrocyte release of K+ through KCa channels (7), which depends on mGluR stimulation of EETs (10, 14). Addition of a Kir antagonist to a cocktail of NOS, adenosine, and EET inhibitors does not produce a substantial additional diminution of the LDF response to whisker stimulation (19). Thus the residual LDF response in our experiments is unlikely to be attributable to activation of Kir channels.

Interestingly, the residual LDF response remained rapid both in onset and offset after inhibition with the drug cocktail. Thus the unidentified residual mechanism of neurovascular coupling has a relatively rapid time constant. One mechanism that has been proposed is based on a sensing mechanism of the NADH redox state that results from the excess glycolysis relative to oxidative metabolism during cortical activation (24). One such sensing mechanism that has been proposed is that the associated increase in lactate will inhibit reuptake of PGE2 and thereby prolong vasodilation (12). However, if the NADH redox state is responsible for the residual vasodilation, another sensing mechanism likely comes into play because the residual response persisted after combined COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition.

It is possible that the various inhibitors used in this study inhibited the increase in glucose consumption evoked by neuronal activation and consequently inhibited the increase in CO2 production. Nevertheless, our conclusion that carbonic acidosis does not explain the residual LDF response after administration of the various inhibitors would still be valid in this case because the postulated mismatch between CO2 production and clearance would be diminished. In this regard, COX-2 gene deletion was reported not to diminish the increase in glucose consumption during whisker stimulation (26).

Recovery of the blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) signal after cessation of activation can sometimes show an undershoot that has been attributed to a delay in the recovery of cerebral blood volume, a delay in the recovery of oxygen consumption, and a decrease in CBF (9). A mathematical model of CO2 kinetics, in which CO2 production is assumed to be proportional to O2 consumption, suggests that feed-forward signaling mechanisms, such as NO, result in a relative hypocapnia that persists into the early recovery period and that may account for the BOLD undershoot (38). However, we found no substantial CBF undershoot under normal conditions and no major effect of inducing alkalosis alone or with inhibitors on the shape of the CBF recovery in our model. The presence of a CBF undershoot may be specific for the type of stimulus and activation pattern.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that COX-2 is more important than COX-1 in mediating the increase in CBF during whisker stimulation in the rat and mouse but that a minimal amount of COX-1 activity appears to play a permissive role in the rat. Moreover, the role of EETs in mediating dilation does not fully require COX-1 or COX-2 activity. Furthermore, carbonic acidosis does not contribute to the normal increase in CBF during activation of rodent whisker barrel cortex or to the residual response after combined inhibition of nNOS, COX-2, mGluR, EETs, COX-1, NMDA receptors, and adenosine A2B receptor pathways. The mechanism of this residual vasodilation may be important in disease states that partially impair normal neurovascular coupling.

GRANTS

The project described was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-59996 (to D. R. Harder and R. C. Koehler), by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-033833 and HL-092105 (to D. R. Harder), and by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM-031278 and the Robert A. Welch Foundation GL-625910 (to J. R. Falck). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: X.L., C.L., and J.R.F. performed experiments; X.L., C.L., and R.C.K. analyzed data; X.L., D.R.H., and R.C.K. interpreted results of experiments; X.L. and R.C.K. prepared figures; X.L. and R.C.K. drafted manuscript; X.L., C.L., J.R.F., D.R.H., and R.C.K. approved final version of manuscript; J.R.F., D.R.H., and R.C.K. edited and revised manuscript; D.R.H. and R.C.K. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Claire F. Levine for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alkayed NJ, Birks EK, Narayanan J, Petrie KA, Kohler-Cabot AE, Harder DR. Role of P-450 arachidonic acid expoygenase in the response of cerebral blood flow to glutamate in rats. Stroke 28: 1066–1072, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bakalova R, Matsuura T, Kanno I. The cyclooxygenase inhibitors indomethacin and Rofecoxib reduce regional cerebral blood flow evoked by somatosensory stimulation in rats. Exp Biol Med 227: 465–473, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brenneis C, Maier TJ, Schmidt R, Hofacker A, Zulauf L, Jakobsson PJ, Scholich K, Geisslinger G. Inhibition of prostaglandin E2 synthesis by SC-560 is independent of cyclooxygenase 1 inhibition. FASEB J 20: 1352–1360, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calcinaghi N, Jolivet R, Wyss MT, Ametamey SM, Gasparini F, Buck A, Weber B. Metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 is not involved in the early hemodynamic response. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31: e1–e10, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dai M, Shi X. Fibro-vascular coupling in the control of cochlear blood flow. PLoS One 6: e20652, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dirnagl U, Niwa K, Lindauer U, Villringer A. Coupling of cerebral blood flow to neuronal activation: role of adenosine and nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H296–H301, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Filosa JA, Bonev AD, Straub SV, Meredith AL, Wilkerson MK, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci 9: 1397–1403, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, Dence C. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science 241: 462–464, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fuchtemeier M, Leithner C, Offenhauser N, Foddis M, Kohl-Bareis M, Dirnagl U, Lindauer U, Royl G. Elevating intracranial pressure reverses the decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin and abolishes the post-stimulus overshoot upon somatosensory activation in rats. Neuroimage 52: 445–454, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gebremedhin D, Yamaura K, Zhang C, Bylund J, Koehler RC, Harder DR. Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation enhances the activities of two types of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurosci 23: 1678–1687, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Girouard H, Bonev AD, Hannah RM, Meredith A, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Astrocytic endfoot Ca2+ and BK channels determine both arteriolar dilation and constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3811–3816, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gordon GR, Choi HB, Rungta RL, Ellis-Davies GC, MacVicar BA. Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature 456: 745–749, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harder DR, Gebremedhin D, Narayanan J, Jefcoat C, Falck JR, Campbell WB, Roman R. Formation and action of a p-450 4A metabolite of arachidonic acid in cat cerebral microvessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H2098–H2107, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higashimori H, Blanco VM, Tuniki VR, Falck JR, Filosa JA. Role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as autocrine metabolites in glutamate-mediated K+ signaling in perivascular astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1068–C1078, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koehler RC, Roman RJ, Harder DR. Astrocytes and the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Trends Neurosci 32: 160–169, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koehler RC, Traystman RJ. Bicarbonate ion modulation of cerebral blood flow during hypoxia and hypercapnia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 243: H33–H40, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kontos HA, Raper AJ, Patterson JL. Analysis of vasoactivity of local pH, PCO2 and bicarbonate on pial vessels. Stroke 8: 358–360, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lecrux C, Toussay X, Kocharyan A, Fernandes P, Neupane S, Levesque M, Plaisier F, Shmuel A, Cauli B, Hamel E. Pyramidal neurons are “neurogenic hubs” in the neurovascular coupling response to whisker stimulation. J Neurosci 31: 9836–9847, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leithner C, Royl G, Offenhauser N, Fuchtemeier M, Kohl-Bareis M, Villringer A, Dirnagl U, Lindauer U. Pharmacological uncoupling of activation induced increases in CBF and CMRO2. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 311–322, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindauer U, Megow D, Matsuda H, Dirnagl U. Nitric oxide: a modulator, but not a mediator, of neurovascular coupling in rat somatosensory cortex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H799–H811, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu X, Li C, Falck JR, Roman RJ, Harder DR, Koehler RC. Interaction of nitric oxide, 20-HETE, and EETs during functional hyperemia in whisker barrel cortex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H619–H631, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu X, Li C, Gebremedhin D, Hwang SH, Hammock BD, Falck JR, Roman RJ, Harder DR, Koehler RC. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-dependent cerebral vasodilation evoked by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H373–H381, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsuura T, Takuwa H, Bakalova R, Obata T, Kanno I. Effect of cyclooxygenase-2 on the regulation of cerebral blood flow during neuronal activation in the rat. Neurosci Res 65: 64–70, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mintun MA, Vlassenko AG, Rundle MM, Raichle ME. Increased lactate/pyruvate ratio augments blood flow in physiologically activated human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 659–664, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nithipatikom K, Grall AJ, Holmes BB, Harder DR, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Liquid chromatographic-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometric analysis of cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid. Anal Biochem 298: 327–336, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Niwa K, Araki E, Morham SG, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Cyclooxygenase-2 contributes to functional hyperemia in whisker-barrel cortex. J Neurosci 20: 763–770, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Niwa K, Haensel C, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Cyclooxygenase-1 participates in selected vasodilator responses of the cerebral circulation. Circ Res 88: 600–608, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paisansathan C, Xu H, Vetri F, Hernandez M, Pelligrino DA. Interactions between adenosine and K+ channel-related pathways in the coupling of somatosensory activation and pial arteriolar dilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H2009–H2017, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park L, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Wang G, Norris EH, Paul J, Strickland S, Iadecola C. Key role of tissue plasminogen activator in neurovascular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 1073–1078, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peng X, Carhuapoma JR, Bhardwaj A, Alkayed NJ, Falck JR, Harder DR, Traystman RJ, Koehler RC. Suppression of cortical functional hyperemia to vibrissal stimulation in the rat by epoxygenase inhibitors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H2029–H2037, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng X, Zhang C, Alkayed NJ, Harder DR, Koehler RC. Dependency of cortical functional hyperemia to forepaw stimulation on epoxygenase and nitric oxide synthase activities in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24: 509–517, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petzold GC, Albeanu DF, Sato TF, Murthy VN. Coupling of neural activity to blood flow in olfactory glomeruli is mediated by astrocytic pathways. Neuron 58: 897–910, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shi Y, Liu X, Gebremedhin D, Falck JR, Harder DR, Koehler RC. Interaction of mechanisms involving epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, adenosine receptors, and metabotropic glutamate receptors in neurovascular coupling in rat whisker barrel cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28: 111–125, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stefanovic B, Bosetti F, Silva AC. Modulatory role of cyclooxygenase-2 in cerebrovascular coupling. Neuroimage 32: 23–32, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, Lou N, Libionka W, Han X, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci 9: 260–267, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ueki M, Linn F, Hossmann KA. Functional activation of cerebral blood flow and metabolism before and after global ischemia of rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 8: 486–494, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vetri F, Xu H, Mao L, Paisansathan C, Pelligrino DA. ATP hydrolysis pathways and their contributions to pial arteriolar dilation in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1369–H1377, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yucel MA, Devor A, Akin A, Boas DA. The possible role of CO2 in producing a post-stimulus CBF and BOLD undershoot. Front Neuroenergetics 1: 7, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zonta M, Angulo MC, Gobbo S, Rosengarten B, Hossmann KA, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci 6: 43–50, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zonta M, Sebelin A, Gobbo S, Fellin T, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Glutamate-mediated cytosolic calcium oscillations regulate a pulsatile prostaglandin release from cultured rat astrocytes. J Physiol 553: 407–414, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]