Abstract

Methionine can be oxidized by reactive oxygen species to a mixture of two diastereomers, methionine-S-sulfoxide and methionine-R-sulfoxide. Both free amino acid and protein-based forms of methionine-S-sulfoxide are stereospecifically reduced by MsrA, whereas the reduction of methionine-R-sulfoxide requires two enzymes, MsrB and fRMsr, which act on its protein-based and free amino acid forms, respectively. However, mammals lack fRMsr and are characterized by deficiency in the reduction of free methionine-R-sulfoxide. The biological significance of such biased reduction of methionine sulfoxide has not been fully explored. MsrA and MsrB activities decrease during aging, leading to accumulation of protein-based and free amino acid forms of methionine sulfoxide. Since methionine is an indispensible amino acid in human nutrition and a key metabolite in sulfur, methylation, and transsulfuration pathways, the consequences of accumulation of its oxidized forms require further studies. Finally, in addition to methionine, methylsulfinyl groups are present in various drugs and natural compounds, and their differential reduction by Msrsmay have important therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Methionine, Methionine sulfoxide reductase, Methionine sulfoxide, Methylsulfinyl-containing compounds, MsrA, MsrB, fRMsr, Sulfur metabolism

Introduction

Methionine (Met) is an important amino acid in human nutrition that is only available from food sources. It is a versatile amino acid at the junction of several metabolic pathways. For example, Met (N-formyl methionine in prokaryotes) is used as the first (N-terminal) amino acid during translation and can often be a limiting factor in protein synthesis, especially under conditions of Met deficiency. Met is also a crucial metabolite that influences redox homeostasis through sulfur metabolism and the transsulfuration pathway (1–6). Met is positioned at the entry point of several metabolic processes and serves as an important regulator of these pathways. It is also the source of several antioxidants and other sulfur compounds, which function in the defense against oxidative stress, such as glutathione (GSH), taurine, and cysteine (Cys), and therefore, Met is a core amino acid that supplies antioxidants to balance the cellular redox status against the attack by reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), another key metabolite produced from Met, is a major methyl donor in cells and an epigenetic regulator (7, 8).

Aerobic organisms generate ROS as products or by-products of mitochondrial respiration, xanthine oxidase, NADPH oxidase, and other metabolic processes and enzymes (9–11). ROS may damage macromolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and DNA, which leads to an increased incidence of disease and accelerated aging (12–16). In the case of protein oxidation, all amino acids are subject to oxidative modification (17). However, Met is one of two common amino acids (together with Cys) that are most susceptible to oxidation by ROS, and therefore enzymatic systems evolved to counteract this damage. In addition, this amino acid may further contribute to antioxidant function when coupled with reductases (18, 19).

Interestingly, Met has a unique oxidation pattern in that two diastereomers are produced, which require separate enzyme systems for their reduction (20). In addition, a new reductase family has recently been discovered that is specific for the reduction of one of two diastereomers of oxidized Met in its free amino acid form. Thus, several enzymes are needed for the reduction of free and protein-based oxidized Met. The biological significance of reversible stereospecific Met oxidation is the subject of this review.

Methionine oxidation by ROS

Methionine sulfoxide is a major product of Metoxidation

Met is highly susceptible to oxidation by ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (19, 21, 22, 23). Generally, all amino acids are subject to free radical-mediated oxidation by radiation, metal-catalyzed reactions, mitochondrial respiration, and many other processes generating ROS, but Met is among the most sensitive to oxidation. In the case of metal ion-catalyzed oxidation, α-carbon of amino acids, including that of Met, can undergo oxidative deamination (17, 24, 25). However, it appears that only ~10% Met is converted to NH4+, RCOO−, and O2, whereas the major product of Met oxidation is Met sulfoxide (17, 25).

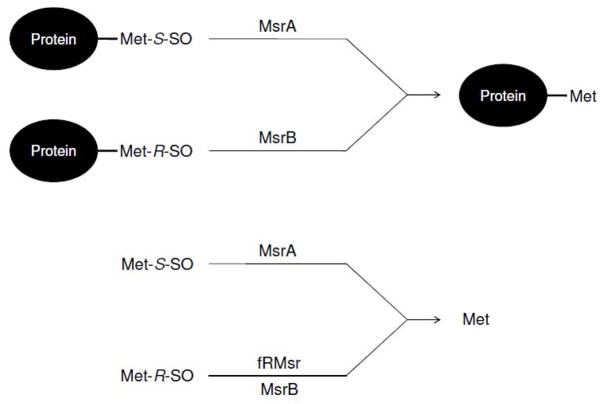

Oxidation of Met to methionine-S-sulfoxide and methionine-R-sulfoxide

Sulfur of Met forms a prochiral center and its oxidation results in two diastereomer products, methionine-S-sulfoxide (Met-S-SO) and methionine-R-sulfoxide (Met-R-SO) (Figure 1). From what we currently know, there is no evidence for preferential formation of one diastereomer of Met sulfoxide over the other in proteins and free amino acid forms, with the exception of enzymatic oxidation by flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (26, 27). Prior to the discovery of Met-R-SO specific reductase, researchers focused on characterizing stereospecific oxidation by ROS because it was known that oxidized Met residues could be completely reduced in vivo, whereas only a Met-S-SO specific reductase was known at the time. However, instead of finding stereospecificity of oxidation, these studies led to the discovery of a new reductase specific for Met-R-SO (28–30).

Figure 1.

Oxidation of Met. ROS can oxidize Met to two diastereomers of Met sulfoxide, Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO.

Reduction of free and protein-based methionine-R,S-sulfoxides by three types of methionine sulfoxide reductase

Function of methionine sulfoxide reductases

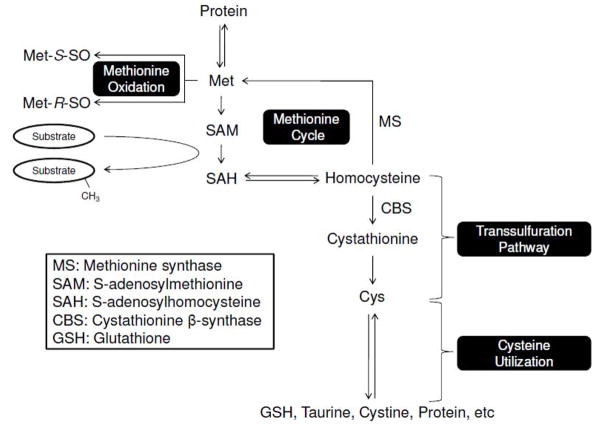

Methionine sulfoxide reductases (Msrs) are thiol (or selenol)-dependent oxidoreductases that reduce protein-based and/or free forms of Met-S-SO or Met-R-SO to Met (Figure 2) (29–36). This function makes these enzymes important antioxidant proteins that can protect against oxidative stress through reversible oxidation and reduction of Met. Also, Msrs may regulate protein function by controlling the redox state of critical Met residues (37–40). One recently described case of such regulation involves CaMKII (calcium/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM)-dependent protein kinase II) protein. This protein is activated by oxidation of two Met residues in the regulatory domain in the absence of Ca2+/CaM and this activation isreversed by MsrA (37).

Figure 2.

Reduction of methionine sulfoxides by three classes of Msr. Protein-based Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO are reduced by MsrA and MsrB, respectively, whereas free Met-S-SO and free Met-R-SO are reduced by MsrA and fRMsr. MsrBs can also contribute to the reduction of free Met-R-SO, but with low efficiency.

Methionine sulfoxide reductase families

Currently, three Msr classesare known, which differ with regard to substrates that they use. The first Msr, methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA), was discovered about 30 years ago as a protein that restored the oxidized form of ribosomal protein L12 in E. coli (31). About 9 years ago, a second Msr was described, now known as methionine sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB), that together with MsrA could fully reduce oxidized calmodulin in E. coli (30). Finally, a GAF domain-containing Msr, free methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase (fRMsr), was recently discovered, also in E. coli(32).

MsrA and MsrB

MsrA is specific for the reduction of free and protein-based Met-S-SO and cannot reduce any form of Met-R-SO (Figure 2) (41–44). On the other hand, this enzyme has a broad substrate specificity and can reduce the S-stereomer forms of other compounds, such as N-acetyl-methionine-S-sulfoxide, ethionine-S-sulfoxide, and S-sulindac (45–47). MsrB (described initially as SelR or SelX) is specific for the reduction of protein-based Met-R-SO, has very low activity with free Met-R-SO (Figure 2) and is characterized by narrow substrate specificity with regard to R-stereomers of various sulfoxides. In support of the fact that MsrA and MsrB have widely different catalytic properties for the reduction of free methionine sulfoxides, E. coli MsrA was shown to possess 1000-fold higher catalytic efficiency for the reduction of free Met-S-SO than E. coli MsrB for the reduction of free Met-R-SO (32). This difference was also supported by a study that examined free methionine sulfoxide reduction in mammals. In this case, human SK-Hep1 cells failed to grow on free Met-R-SO supplemented media lacking Met, whereas they grew well on the corresponding Met-S-SO supplemented media. This was because these cells efficiently reduced free MetS-SO by MsrA and utilized the resulting Met, whereas free Met-R-SO was not reduced by MsrBs( 48).

Free methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase

fRMsr catalyzes the reduction of free Met-R-SO (32, 48, 49). This enzyme is highly specific for free MetR-SO and does not reduce protein-based sulfoxides (Figure 2), compensating for the low activity of MsrB for free Met-R-SO. Thus, the three types of Msr can be a part of jigsaw for the complete reduction of methionine sulfoxides in free and protein-based forms. However, fRMsr was lost during evolution and its occurrence, based on comparative genomic analysis, is limited to unicellular organisms, whereas multicellular organisms, including mammals and plants, lack this protein (32, 49).

Methionine and methionine sulfoxide in cells and organisms

Biased methionine sulfoxide reduction

Some 20 years ago, there was an interesting report of free methionine sulfoxide levels in human urine with severe hepatic methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) deficiency (50). In this study, sulfur-containing compounds were analyzed using ninhydrin assays. Of the total sulfur excretion in urine, approximately 7% was methionine sulfoxide, while approximately 4.5% was free and protein-based methionine. Interestingly, only a single methionine sulfoxide form, methionine-R-sulfoxide, was identified in this analysis. If Met is oxidized by ROS randomly to two diastereomers (28), low efficiency of the reduction of free Met-R-SO might be the reason for the biased methionine sulfoxide composition in urine. This unbalanced composition was also found in mouse plasma (48). In this experiment, significant levels of free Met-R-SO were present (~ 9 μM), while free Met-S-SO was not detected, probably because it was completely reduced by MsrA. However, approximately 14 μM free Met-S-SO was found in plasma of MsrA knockout mice, which is consistent with the idea that MsrA was responsible for the complete reduction of Met-S-SO in mouse plasma (48). As mentioned above, higher eukaryotes including mammals lack fRMsr and thus accumulation of this sulfoxide form occurred in urine and blood.

Aging and methionine sulfoxide

Several studies provided evidence that MsrA and MsrB activities decrease during aging and in disease conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease (51–54). This activity decline might affect protein-based and free methionine sulfoxide levels. Indeed, numerous studies reported that methionine sulfoxide in proteins increases during aging and in certain diseases (55–57). Though little is currently known with regard to changes in free Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO levels during aging, it may be predicted that these metabolites also increase during aging due to a decreased MsrA activity and occurrence of catalytically inefficient MsrBs. Therefore, methionine sulfoxides may represent useful biomarkers of redox changes during aging and disease. To explore the potential of such biomarkers, several studies focused on developing antibodies specific for methionine sulfoxides in proteins, so far with little success (58,59). In these experiments, antibodies against oxidized recombinant Met-rich proteins were tested for detecting Met oxidation of endogenous proteins. Most of them could not detect Met oxidation of cellular proteins, although one study did report detection of IgG and prion (59). However, sensitivity and specificity of these tools for oxidized Met requires improvement in order to be used as an accurate sensor. Availability of antibodies with specificity for Met sulfoxide could provide broad range recognition of Met sulfoxides in vivo, especially in aging, cancer, neurodegeneration, and many other disease conditions. If developed, these antibodies could become an extremely useful tool to study oxidative protein damage and repair and to monitor Met oxidation and reduction under physiological conditions.

Methionine, sulfur metabolism and control of redox homeostasis: what are the roles of Msrs in this pathway?

Methionine metabolism and the response to oxidative stress

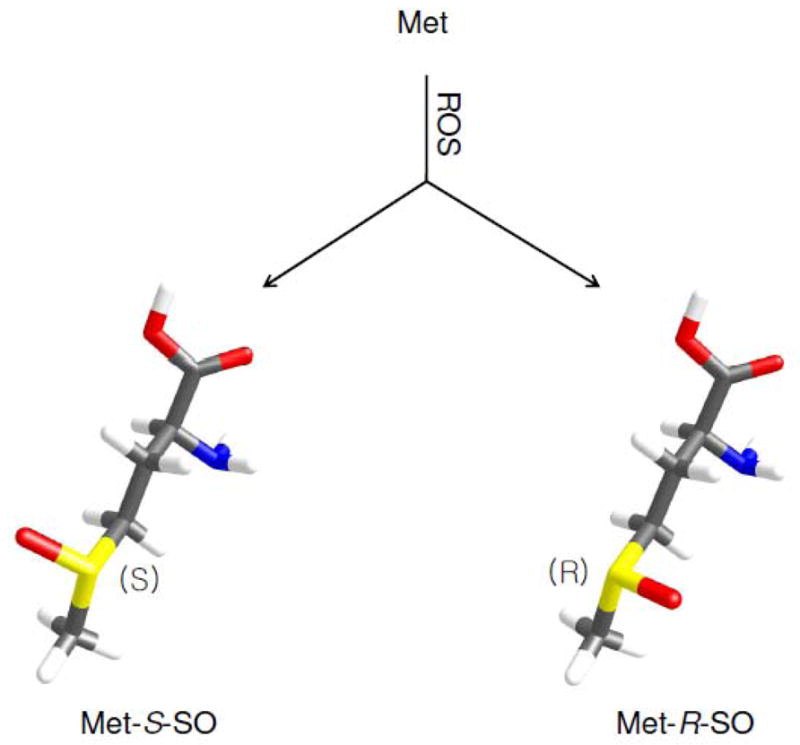

Methionine (Met) is located at the key junction in sulfur metabolism. It has a central role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis, serves as a donor of methyl groups, and is a precursor for other sulfur-containing amino acids and compounds (Figure 3) (1, 60–62). Being an indispensible dietary amino acid, Met cannot be synthesized or replaced by other amino acids in mammals, while cysteine (Cys), which is another sulfur amino acid, can be generated from Met through the transsulfuration pathway (Figure 1). To defend against oxidative stress, this pathway provides, among other compounds, glutathione (GSH). GSH participates in redox regulation and scavenging ROS by being a substrate for several enzymes, such as glutathione reductase that reduces oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and glutathione peroxidase that reduces organic and lipid peroxides in a GSH-dependent manner (63). GSH also can be used for the reduction of glutaredoxin, which deglutathionylates target proteins and transfers reducing equivalents to enzymes and compounds such as dehydroascorbic acid, peroxiredoxin, and Msrs (64–68). The GSH/GSSG ratio varies among tissues and cellular compartments and serves as an indicator of redox status. To avoid collapse of redox homeostasis upon oxidative stress, organisms can support de novo GSH synthesis from Met (4). For example, inhibition of methionine synthase (MS) activity leads to accumulation of homocysteine, enhancing Cys synthesis through the transsulfuration pathway. In addition, the activity of cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) may be stimulated to generate Cys from homocysteine (5, 6). Ultimately, this pathway produces GSH from Met to regulate redox homeostasis.

Figure 3.

Pathways of Met utilization. The overall Met metabolism can be subdivided into two systems: the methionine/methylation cycle, and the transsulfuration pathway. In addition, cysteine utilization depends on Met. The subject of this review is reversible Met oxidation that so far received little attention with regard to regulating Met fluxes.

Oxidative stress and methionine sulfoxide reductases

CBS has an important regulatory role as a key enzyme in the transsulfuration pathway (Figure 3). With regard to oxidative stress, this enzyme is subject to regulation by S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM is an allosteric regulator of CBS that may increase its activity 2–3 fold and may also affect its stability under conditions of Met restriction (69). Low levels of Met lead to a decrease in SAM levels thus destabilizing CBS, inhibiting the transsulfuration pathway and preserving Met for methylation at the expense of GSH synthesis. As mentioned above, oxidative stress can stimulate this enzyme and thus produce more GSH. However, oxidative stress also contributes to Met oxidation, which would prohibit conversion of this amino acid to SAM by methionine adenosyltransferase. Under normal conditions, free Met-S-SO may be reduced by MsrA to provide Met for Met metabolism whereas free Met-R-SO may be released through the urinary system. The fact that free Met-S-SO was not detected in mouse blood is supportive of the idea that the MsrA function is sufficient in providing Met by the reduction of free Met-S-SO. But if cells are subjected to stronger oxidative stress and MsrA activity is decreased (e.g., during aging), what would happen to Met metabolism? Probably, Met will be more oxidized thus effectively decreasing Met levels. Indeed, it was reported that Met levels decrease during aging in fruit flies (70). Increased Met oxidation might be a factor that contributes to this effect. What would then be the consequence of a decrease in Met as a result of increased Met sulfoxides? Though it remains to be investigated, it is possible that the decreased Met will destabilize CBS, while MS might still be restricted in its activity for remethylating homocysteine because of oxidative stress. Therefore, this might result in accumulation of homocysteine, which is a known marker of diseases such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases (71). In addition, hydrolysis of S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) is reversible and accumulated homocysteine can be converted back to SAH inhibiting cellular methylation by SAM. Prolonged unbalance between SAM and SAH during oxidative stress coupled with the reduced Met levels might also cause serious defects to epigenetic regulation. It should be noted, however, that further studies are needed to better understand physiological consequences of decreased Met:

Met flux under Met deficiency conditions and increased oxidative stress. Most likely, conversion of Met to SAM will be increased because MAT activity depends on SAM and therefore this may affect Met flux through various pathways dependent on this amino acid. In support of this idea, it was reported that addition of Met sulfoxide under conditions of Met deficiency increased MAT activity in E. coli (72). But it also raises a question of how this nutritional distribution affects other metabolic processes during aging. Even if MAT is sufficient to fulfill the SAM demand, it might lead to Met levels that cannot fully support other processes such as protein synthesis.

Inhibitory effect of methionine sulfoxide. It is possible that Met sulfoxide may act as an inhibitor of Met metabolism. Human s have three isoforms of MAT ( MAT1A, MAT2A, MAT 2B). It would be interesting to test if Met sulfoxide inhibits these enzymes.

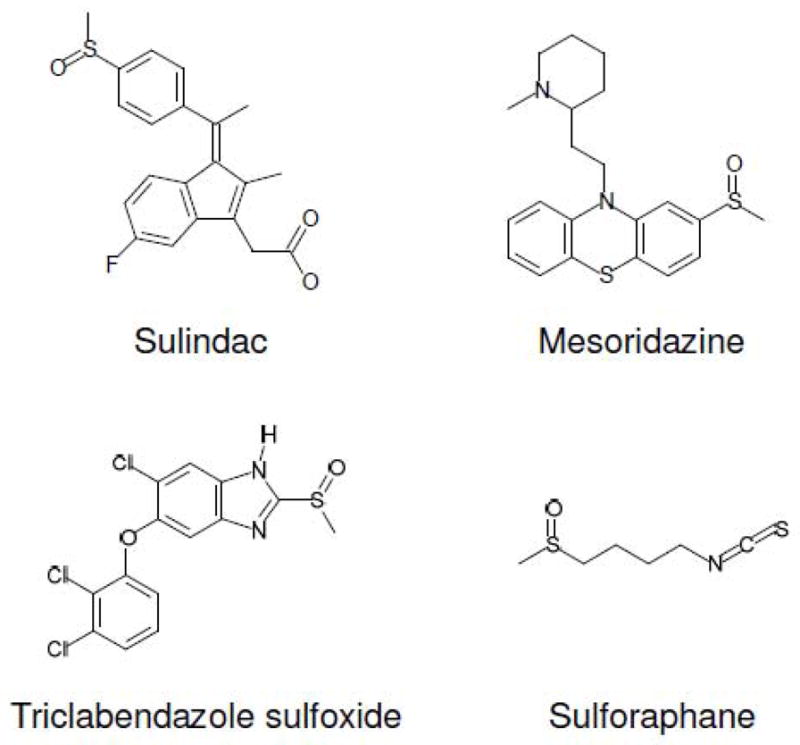

Reduction of methylsulfinyl-containing drugs and natural compounds

The methylsulfide group of Met is the site of oxidation to form a mixture of two diastereomers, Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO. Like Met, numerous natural compounds and drugs contain methylsulfinyl or methylsulfide groups (Figure 4) and may be subject to further metabolic reactions (73–76). For example, it was found that cytochrome p450 (Cyp450) inserts one atom of oxygen onto carbon or sulfur in various substrates and thus this enzyme may promote oxidation of certain methylsulfides to methylsulfinyls (74, 75). Also, flavin monooxygenase can oxidize sulfur in some compounds (76). It appears that oxidation of methylsulfides occurs in vivo and therefore, certain enzymes may contribute to oxidation of methylsulfides in drugs and natural compounds (77–81). Like oxidation of Met that gives rise to two diastereomers, oxidation of other methylsulfides will also result in two diastereomer forms, S- and R-sulfoxide, because sulfur in these compounds is a prochiral center. Sulfoxidation of methylsulfide may change properties of these compounds, such as hydrophobicity, drug-drug interactions, affinity for protein targets, and transport across membranes. For example, mesoridazine (oxidized form of thioridazine) (Figure 4) was found to have stronger binding affinity for dopaminergic and α-adrenergic receptors, but lower affinity for muscarinic receptor, than thioridazine, and this difference correlated with clinical data on side effects depending on the use of these types of drugs (77). In a study of triclabendazole (TCBZ) (Figure 4) that is a drug for common liver fluke, F. hepatica, TCBZ-resistant F. hepatica showed higher sulfoxidation capacity of TCBZ than TCBZ-susceptible organisms wherein triclabendazole sulfoxide (TCBZSO) may be prone to oxidation to triclabendazole sulfone (TCBZSO2), a compound with reduced pharmacological potency (Figure 4) (78). In addition, it was recently shown that the sulfoxide moiety of sulforaphane influenced induction of NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase (NQO1) activity. The sulfoxide form of sulforaphane required the concentration of 0.22 μM to double the activity of this enzyme, while the sulfide form required 2.3 μM. Thus, it appears that sulfoxidation of methylsulfide in sulforaphane increased its potency approximately 10 fold (82).

Figure 4.

Methylsulfinyl-containing drugs and compounds.

In contrast to oxidative modification of xenobiotics, reductive modifications of oxidized compounds received less attention and little information is currently known regarding sulfoxides. It is possible that the sulfoxide moieties of many drugs are targets for Msrs. Although chemical structures of Met sulfoxide and methylsulfinyl-containing drugs are different, it is not known how this affects the reduction of sulfoxides. Interestingly, sulindac is known for its anti-inflammatory and more recently for anti-tumorigenic activities and it has a methylsulfinyl group (47). It could be stereospecifically reduced by E. coli MsrA, but not by E. coli MsrB. Perhaps MsrA, which is known for its broad substrate specificity, recognized the S-sulfoxide form of this drug. These considerations offer new insights into drug metabolism and may provide therapeutic opportunities for increased efficacy of drugs and natural compoundsby utilizing a particular diastereomer of sulfoxide in these chemicals.

Conclusions

Met is an essential amino acid involved in several critical metabolic processes. In mammals, it can be obtained only from diet and is susceptible to oxidation at its sulfur atom under physiological conditions. Oxidation of Met may be reversed by three Msr families with the help of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Among these enzymes, MsrA and MsrB have complementary roles in reducing two diastereomers of oxidized Met in proteins, but this partnership breaks down when it comes to free Met sulfoxides due to inability of MsrBs to reduce free Met-R-SO. Although fRMsr reduces free Met-R-SO, this enzyme is only present in unicellular organisms, and thus mammals are unable to reduce this compound. Met is required for protein synthesis, sulfur metabolism, methylation, redox regulation and signal transduction, but at the same time mammals do not possess an enzymatic system to synthesize this amino acid, whose only sources are diet and recycling. Therefore, delicate control of Met metabolism is important in order to supply this amino acid for diverse cellular needs. In this regard, susceptibility to oxidation and availability of repair enzymes may be important factors that regulate Met flux, especially under conditions of oxidative stress. However, these factors received little attention to date and should be examined in future studies. Finally, the difference in the ability of MsrA and MsrB to reduce free Met sulfoxides may be relevant to the metabolism of other compounds that contain methylsulfinyl groups. For example, an anti-cancer compound sulindac could only be reduced by E. coli MsrA. It would be important to examine other methylsulfinyl-containing drugs for being Msr substrates and for differential therapeutic potency of their diastereomer forms. Such studies may open avenues for increasing efficacy of drugs and natural compounds containing methylsulfinyl groups.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH AG021518.

Abbreviations

- GSH

Glutathione

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- CBS

Cystathionine β-synthase

- MS

Methionine synthase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Met-R-SO

Methionine-R-sulfoxide

- Met-S-SO

Methionine-S-sulfoxide

- Msr

Methionine sulfoxide reductase

- MAT

Methionine adenosyltransferase

- Cyp450

Cytochrome p450

- TCBZ

Triclabendazole

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Metayer S, Seiliez I, Collin A, Duchene S, Mercier Y, Geraert PA, Tesseraud S. Mechanisms through which sulfur amino acids control protein metabolism and oxidative status. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deth R, Muratore C, Benzecry J, Power-Charnitsky VA, Waly M. How environmental and genetic factors combine to cause autism: A redox/methylation hypothesis. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou CG, Banerjee R. Homocysteine and redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:547–559. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebrin I, Sohal RS. Pro-oxidant shift in glutathione redox state during aging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1545–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mato JM, Martinez-Chantar ML, Lu SC. Methionine metabolism and liver disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:273–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME. The sulfur-containing amino acids: An overview. J Nutr. 2006;136:1636S–1640S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1636S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterland RA. Assessing the effects of high methionine intake on DNA methylation. J Nutr. 2006;136:1706S–1710S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1706S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulrey CL, Liu L, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO. The impact of metabolism on DNA methylation. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(Spec No 1):R139–47. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza-Pinto NC, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison R. Structure and function of xanthine oxidoreductase: Where are we now? Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:774–797. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00956-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambeth JD. Nox enzymes, ROS, and chronic disease: An example of antagonistic pleiotropy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:332–347. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo T, Hirose M, Kageyama K. Roles of oxidative stress and redox regulation in atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16:532–538. doi: 10.5551/jat.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu T, Finkel T. Free radicals and senescence. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:1918–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage alzheimer’s disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7497–7504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polidori MC, Griffiths HR, Mariani E, Mecocci P. Hallmarks of protein oxidative damage in neurodegenerative diseases: Focus on alzheimer’s disease. Amino Acids. 2007;32:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stadtman ER. Oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins by radiolysis and by metal-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:797–821. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.004053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalle-Donne I, Rossi R, Giustarini D, Gagliano N, Di Simplicio P, Colombo R, Milzani A. Methionine oxidation as a major cause of the functional impairment of oxidized actin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogt W. Oxidation of methionyl residues in proteins: Tools, targets, and reversal. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00158-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee BC, Dikiy A, Kim HY, Gladyshev VN. Functions and evolution of selenoprotein methionine sulfoxide reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1471–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tien M, Berlett BS, Levine RL, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. Peroxynitrite-mediated modification of proteins at physiological carbon dioxide concentration: PH dependence of carbonyl formation, tyrosine nitration, and methionine oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7809–7814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chao CC, Ma YS, Stadtman ER. Modification of protein surface hydrophobicity and methionine oxidation by oxidative systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2969–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavine TF. The formation, resolution, and optical properties of the diastereoisomeric sulfoxides derived from L-methionine. J Biol Chem. 1947;169:477–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berlett BS, Chock PB, Yim MB, Stadtman ER. Manganese(II) catalyzes the bicarbonate-dependent oxidation of amino acids by hydrogen peroxide and the amino acid-facilitated dismutation of hydrogen peroxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:389–393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stadtman ER, Berlett BS. Fenton chemistry amino acid oxidation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17201–17211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ripp SL, Itagaki K, Philpot RM, Elfarra AA. Methionine S-oxidation in human and rabbit liver microsomes: Evidence for a high-affinity methionine S-oxidase activity that is distinct from flavin-containing monooxygenase 3. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;367:322–332. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dever JT, Elfarra AA. In vivo metabolism of L-methionine in mice: Evidence for stereoselective formation of methionine-d-sulfoxide and quantitation of other major metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:2036–2043. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharov VS, Schoneich C. Diastereoselective protein methionine oxidation by reactive oxygen species and diastereoselective repair by methionine sulfoxide reductase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:986–994. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kryukov GV, Kumar RA, Koc A, Sun Z, Gladyshev VN. Selenoprotein R is a zinc-containing stereo-specific methionine sulfoxide reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4245–4250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072603099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimaud R, Ezraty B, Mitchell JK, Lafitte D, Briand C, Derrick PJ, Barras F. Repair of oxidized proteins. identification of a new methionine sulfoxide reductase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48915–48920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caldwell P, Luk DC, Weissbach H, Brot N. Oxidation of the methionine residues of escherichia coli ribosomal protein L12 decreases the protein’s biological activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:5349–5352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Z, Johnson LC, Weissbach H, Brot N, Lively MO, Lowther WT. Free methionine-(R)-sulfoxide reductase from escherichia coli reveals a new GAF domain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9597–9602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HY, Zhang Y, Lee BC, Kim JR, Gladyshev VN. The selenoproteome of clostridium sp. OhILAs: Characterization of anaerobic bacterial selenoprotein methionine sulfoxide reductase A. Proteins. 2009;74:1008–1017. doi: 10.1002/prot.22212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowther WT, Brot N, Weissbach H, Honek JF, Matthews BW. Thiol-disulfide exchange is involved in the catalytic mechanism of peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6463–6468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowther WT, Weissbach H, Etienne F, Brot N, Matthews BW. The mirrored methionine sulfoxide reductases of neisseria gonorrhoeae pilB. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nsb783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le DT, Lee BC, Marino SM, Zhang Y, Fomenko DE, Kaya A, Hacioglu E, Kwak GH, Koc A, Kim HY, Gladyshev VN. Functional analysis of free methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase from saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4354–4364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805891200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O’Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su Z, Limberis J, Martin RL, Xu R, Kolbe K, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T, Cox BF, Gintant GA. Functional consequences of methionine oxidation of hERG potassium channels. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ezraty B, Grimaud R, El Hassouni M, Moinier D, Barras F. Methionine sulfoxide reductases protect ffh from oxidative damages in escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2004;23:1868–1877. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carruthers NJ, Stemmer PM. Methionine oxidation in the calmodulin-binding domain of calcineurin disrupts calmodulin binding and calcineurin activation. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3085–3095. doi: 10.1021/bi702044x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boschi-Muller S, Gand A, Branlant G. The methionine sulfoxide reductases: Catalysis and substrate specificities. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharov VS, Ferrington DA, Squier TC, Schoneich C. Diastereoselective reduction of protein-bound methionine sulfoxide by methionine sulfoxide reductase. FEBS Lett. 1999;455:247–250. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boschi-Muller S, Gand A, Branlant G. The methionine sulfoxide reductases: Catalysis and substrate specificities. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boschi-Muller S, Olry A, Antoine M, Branlant G. The enzymology and biochemistry of methionine sulfoxide reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moskovitz J, Weissbach H, Brot N. Cloning the expression of a mammalian gene involved in the reduction of methionine sulfoxide residues in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2095–2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weissbach H, Resnick L, Brot N. Methionine sulfoxide reductases: History and cellular role in protecting against oxidative damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etienne F, Resnick L, Sagher D, Brot N, Weissbach H. Reduction of sulindac to its active metabolite, sulindac sulfide: Assay and role of the methionine sulfoxide reductase system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:1005–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee BC, Le DT, Gladyshev VN. Mammals reduce methionine-S-sulfoxide with MsrA and are unable to reduce methionine-R-sulfoxide, and this function can be restored with a yeast reductase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28361–28369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805059200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Le DT, Lee BC, Marino SM, Zhang Y, Fomenko DE, Kaya A, Hacioglu E, Kwak GH, Koc A, Kim HY, Gladyshev VN. Functional analysis of free methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase from saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4354–4364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805891200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gahl WA, Bernardini I, Finkelstein JD, Tangerman A, Martin JJ, Blom HJ, Mullen KD, Mudd SH. Transsulfuration in an adult with hepatic methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:390–397. doi: 10.1172/JCI113331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Novoselov SV, Kim HY, Hua D, Lee BC, Astle CM, Harrison DE, Friguet B, Moustafa ME, Carlson BA, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Regulation of selenoproteins and methionine sulfoxide reductases A and B1 by age, calorie restriction, and dietary selenium in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:829–838. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picot CR, Perichon M, Cintrat JC, Friguet B, Petropoulos I. The peptide methionine sulfoxide reductases, MsrA and MsrB (hCBS-1), are downregulated during replicative senescence of human WI-38 fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 2004;558:74–78. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petropoulos I, Mary J, Perichon M, Friguet B. Rat peptide methionine sulphoxide reductase: Cloning of the cDNA, and down-regulation of gene expression and enzyme activity during aging. Biochem J. 2001;355:819–825. doi: 10.1042/bj3550819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabbita SP, Aksenov MY, Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. Decrease in peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase in alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1660–1666. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stadtman ER, Van Remmen H, Richardson A, Wehr NB, Levine RL. Methionine oxidation and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horstmann HJ, Rohen JW, Sames K. Age-related changes in the composition of proteins in the trabecular meshwork of the human eye. Mech Ageing Dev. 1983;21:121–136. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(83)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wells-Knecht MC, Lyons TJ, McCance DR, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Age-dependent increase in ortho-tyrosine and methionine sulfoxide in human skin collagen is not accelerated in diabetes. evidence against a generalized increase in oxidative stress in diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:839–846. doi: 10.1172/JCI119599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Le DT, Liang X, Fomenko DE, Raza AS, Chong CK, Carlson BA, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Analysis of methionine/selenomethionine oxidation and methionine sulfoxide reductase function using methionine-rich proteins and antibodies against their oxidized forms. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6685–6694. doi: 10.1021/bi800422s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oien DB, Canello T, Gabizon R, Gasset M, Lundquist BL, Burns JM, Moskovitz J. Detection of oxidized methionine in selected proteins, cellular extracts and blood serums by novel anti-methionine sulfoxide antibodies. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;485:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomez J, Caro P, Sanchez I, Naudi A, Jove M, Portero-Otin M, Lopez-Torres M, Pamplona R, Barja G. Effect of methionine dietary supplementation on mitochondrial oxygen radical generation and oxidative DNA damage in rat liver and heart. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riedijk MA, Stoll B, Chacko S, Schierbeek H, Sunehag AL, van Goudoever JB, Burrin DG. Methionine transmethylation and transsulfuration in the piglet gastrointestinal tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3408–3413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607965104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ball RO, Courtney-Martin G, Pencharz PB. The in vivo sparing of methionine by cysteine in sulfur amino acid requirements in animal models and adult humans. J Nutr. 2006;136:1682S–1693S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1682S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamoto Y, Koh YH, Park YS, Fujiwara N, Sakiyama H, Misonou Y, Ookawara T, Suzuki K, Honke K, Taniguchi N. Oxidative stress caused by inactivation of glutathione peroxidase and adaptive responses. Biol Chem. 2003;384:567–574. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernandes AP, Holmgren A. Glutaredoxins: Glutathione-dependent redox enzymes with functions far beyond a simple thioredoxin backup system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:63–74. doi: 10.1089/152308604771978354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wells WW, Xu DP, Yang YF, Rocque PA. Mammalian thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) and protein disulfide isomerase have dehydroascorbate reductase activity. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15361–15364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rouhier N, Gelhaye E, Jacquot JP. Glutaredoxin-dependent peroxiredoxin from poplar: Protein-protein interaction and catalytic mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13609–13614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarrago L, Laugier E, Zaffagnini M, Marchand C, Le Marechal P, Rouhier N, Lemaire SD, Rey P. Regeneration mechanisms of arabidopsis thaliana methionine sulfoxide reductases B by glutaredoxins and thioredoxins. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18963–18971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kwak GH, Kim MJ, Kim HY. Cysteine-125 is the catalytic residue of saccharomyces cerevisiae free methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;395:412–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prudova A, Bauman Z, Braun A, Vitvitsky V, Lu SC, Banerjee R. S-adenosylmethionine stabilizes cystathionine beta-synthase and modulates redox capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6489–6494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509531103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rebrin I, Bayne AC, Mockett RJ, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Free aminothiols, glutathione redox state and protein mixed disulphides in aging drosophila melanogaster. Biochem J. 2004;382:131–136. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zou CG, Banerjee R. Homocysteine and redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:547–559. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greene RC, Radovich C. Role of methionine in the regulation of serine hydroxymethyltransferase in eschericia coli. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:269–278. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.269-278.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baillie TA. Metabolism and toxicity of drugs. two decades of progress in industrial drug metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:129–137. doi: 10.1021/tx7002273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lynch T, Price A. The effect of cytochrome P450 metabolism on drug response, interactions, and adverse effects. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bentley R. Role of sulfur chirality in the chemical processes of biology. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34:609–624. doi: 10.1039/b418284g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beedham C. The role of non-P450 enzymes in drug oxidation. Pharm World Sci. 1997;19:255–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1008668913093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bylund DB. Interactions of neuroleptic metabolites with dopaminergic, alpha adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;217:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alvarez LI, Solana HD, Mottier ML, Virkel GL, Fairweather I, Lanusse CE. Altered drug influx/efflux and enhanced metabolic activity in triclabendazole-resistant liver flukes. Parasitology. 2005;131:501–510. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005007997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brennan GP, Fairweather I, Trudgett A, Hoey E, McCoy, McConville M, Meaney M, Robinson M, McFerran N, Ryan L, Lanusse C, Mottier L, Alvarez L, Solana H, Virkel G, Brophy PM. Understanding triclabendazole resistance. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;82:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mestorino N, Formentini EA, Lucas MF, Fernandez C, Modamio P, Hernandez EM, Errecalde JO. Pharmacokinetic disposition of triclabendazole in cattle and sheep; discrimination of the order and the rate of the absorption process of its active metabolite triclabendazole sulfoxide. Vet Res Commun. 2008;32:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s11259-007-9000-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roth W. Rapid, sensitive and fully automated high-performance liquid chromatographic assay with fluorescence detection for sulmazole and metabolites. J Chromatogr. 1983;278:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)84794-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ahn YH, Hwang Y, Liu H, Wang XJ, Zhang Y, Stephenson KK, Boronina TN, Cole RN, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P, Cole PA. Electrophilic tuning of the chemoprotective natural product sulforaphane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9590–9595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004104107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]