Abstract

Functional constitutive nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is required for full expression of reflex cutaneous vasodilation that is attenuated in aged skin. Both the essential cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and adequate substrate concentrations are necessary for the functional synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) through NOS, both of which are reduced in aged vasculature through increased oxidant stress and upregulated arginase, respectively. We hypothesized that acute local BH4 administration or arginase inhibition would similarly augment reflex vasodilation in aged skin during passive whole body heat stress. Four intradermal microdialysis fibers were placed in the forearm skin of 11 young (22 ± 1 yr) and 11 older (73 ± 2 yr) men and women for local infusion of 1) lactated Ringer, 2) 10 mM BH4, 3) 5 mM (S)-(2-boronoethyl)-l-cysteine + 5 mM Nω-hydroxy-nor-l-arginine to inhibit arginase, and 4) 20 mM NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) to inhibit NOS. Red cell flux was measured at each site by laser-Doppler flowmetry (LDF) as reflex vasodilation was induced. After a 1.0°C rise in oral temperature (Tor), mean body temperature was clamped and 20 mM l-NAME was perfused at each site. Cutaneous vascular conductance was calculated (CVC = LDF/mean arterial pressure) and expressed as a percentage of maximum (%CVCmax; 28 mM sodium nitroprusside and local heat, 43°C). Vasodilation was attenuated at the control site of the older subjects compared with young beginning at a 0.3°C rise in Tor. BH4 and arginase inhibition both increased vasodilation in older (BH4: 55 ± 5%; arginase-inhibited: 47 ± 5% vs. control: 37 ± 3%, both P < 0.01) but not young subjects compared with control (BH4: 51 ± 4%CVCmax; arginase-inhibited: 55 ± 4%CVCmax vs. control: 56 ± 6%CVCmax, both P > 0.05) at a 1°C rise in Tor. With a 1°C rise in Tor, local BH4 increased NO-dependent vasodilation in the older (BH4: 31.8 ± 2.4%CVCmax vs. control: 11.7 ± 2.0%CVCmax, P < 0.001) but not the young (BH4: 23 ± 4%CVCmax vs. control: 21 ± 4%CVCmax, P = 0.718) subject group. Together these data suggest that reduced BH4 contributes to attenuated vasodilation in aged human skin and that BH4 NOS coupling mechanisms may be a potential therapeutic target for increasing skin blood flow during hyperthermia in older humans.

Keywords: skin blood flow, aging, temperature regulation, tetrahydrobiopterin, nitric oxide synthase

skin blood flow (SkBF) is controlled by dual sympathetic innervation consisting of an adrenergic vasoconstrictor system and a cholinergic active vasodilator system (7). With increasing body temperature, SkBF first increases through passive withdrawal of tonic adrenergic vasoconstrictor tone and then increases further through the active vasodilator system (35). Active vasodilation is mediated by the release of acetylcholine and unknown cotransmitter(s) (21), which mediate cutaneous vasodilation in part through nitric oxide (NO)-dependent mechanisms. NO is required for full expression of reflex vasodilation and directly contributes ∼30–40% to the total vasodilatory response (20, 37) in young healthy humans.

Primary human aging is associated with an attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilation response (24) due to a decreased cotransmitter and attenuated NO-dependent contributions (11). The decrease in NO bioavailability in aged human skin results from both a decrease in NO production through mechanisms including upregulated arginase and increased NO degradation through increased oxidant stress (16, 18). These mechanisms may be linked through the uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). NOS is a dimeric enzyme, requiring coupling of the oxygenase and reductase domains for NO production (1, 34). In conditions where substrate (l-arginine) is limited by increased arginase activity or oxidant stress, the NOS dimer is destabilized and produces superoxide rather than functional NO (31, 38).

In addition to upregulated arginase activity and increased oxidative stress, there are other potential mechanisms that may contribute to NOS uncoupling and attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged skin. In addition to adequate l-arginine concentrations, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is also required as a cofactor for optimal NOS function (30, 38). Mechanistically, BH4 stabilizes the functional conformation of the NOS dimer and reduces oxidant stress both within and around the NOS molecule (34, 38). In conditions where BH4 is limited, the NOS dimer uncouples (4). Superoxide produced from uncoupled NOS further oxidizes BH4, which contributes to increased oxidant stress and results in endothelial dysfunction (38). In vivo human studies demonstrate that administration of exogenous BH4 increases measures of NO-dependant vasodilation, including 1) flow-mediated vasodilation in conduit arteries and 2) vasodilation in response to the endothelium-dependent agonist acetylcholine in resistance vessels (9). However, the functional role of BH4 in NOS uncoupling and its potential contribution to attenuated NO-dependent reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged humans is unclear.

The purpose of this study was to determine if exogenous localized administration of BH4 would increase NO-dependent reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged humans. We hypothesized that NOS uncoupling mechanisms contribute to decreased functional NO synthesis and attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin. We further hypothesized that acute local BH4 administration or arginase inhibition, although mechanistically different, would similarly augment reflex vasodilation in aged skin during passive whole body heat stress.

METHODS

Subjects.

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Pennsylvania State University. Written and verbal consent were obtained voluntarily from all subjects before participation according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Studies were performed on 11 young (23 ± 3 yr, 7 men and 4 women) and 11 older (73 ± 2 yr, 5 men and 6 women) healthy subjects. Subjects were screened for neurological, cardiovascular, and dermatological diseases and underwent a complete medical screening including resting electrocardiogram, physical examination, lipid profile, blood chemistry (Quest Diagnostics Nichol Institute, Chantilly, VA), and V̇o2 max test to test for the prevalence of underlying cardiovascular disease. All subjects were normally active, nonhypertensive, nondiabetic, healthy nonsmokers who were not taking prescription medications with primary or secondary vascular effects. Subjects who were taking 81 mg aspirin daily as a preventative measure were required to cease treatment for at least two weeks before the study visit (32). All young women were normally menstruating and were studied during the early follicular phase (days 1–7) of their menstrual cycle. One older subject was retested within six weeks of their primary study visit to repeat a control site that had failed during the initial experiment.

Instrumentation.

All protocols were performed in a thermoneutral laboratory with the subject in a semisupine position and the experimental arm supported at heart level. Upon arrival to the laboratory, subjects were instrumented with four intradermal microdialysis (MD) fibers (10-mm, 30-kDa cutoff membrane, MD 2000; Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN) placed in the skin of the ventral left forearm using sterile technique. MD sites were at least 4 cm apart to ensure no cross-reactivity of pharmacological agents. Before MD fiber placement, ice packs were applied to the MD sites for 5 min to temporarily anesthetize the skin (10). For each fiber, a 25-guage needle was inserted horizontally into the intradermal layers such that the entry and exit points were ∼2.5 cm apart. MD fibers were then threaded through the lumen of the guide needle, and the needle was removed leaving the MD fiber in place. The MD fibers were randomly assigned to receive 1) lactated Ringer solution to serve as control, 2) 10 mM BH4 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for BH4 administration, 3) 20 mM NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NAME; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) to inhibit NOS, and 4) 5 mM (S)-(2-boronoethyl)-l-cysteine (BEC; Calbiochem) + 5 mM Nω-hydroxy-nor-l-arginine (nor-NOHA; Calbiochem) to inhibit arginase (18). All pharmacological agents were mixed just before usage, dissolved in lactated Ringer solution, sterilized with syringe microfilters (Acrodisc; Pall, Ann Arbor, MI), and wrapped in foil to prevent degradation of the drug due to light exposure. During the insertion trauma resolution period (60–90 min), solutions were perfused through the MD fibers at a rate of 2 μl/min (Bee Hive controller and Baby Bee microinfusion pumps; Bioanalytical Systems). Pilot studies were conducted to determine the optimal concentration of BH4, defined as a dose that would augment reflex vasodilator function but did not alter baseline SkBF. Twenty-millimolar l-NAME concentrations were used for NOS inhibition. We and others have previously used 10 mM l-NAME in similar studies. In pilot work, we find that concentrations >5 mM do not produce further reductions in NO-dependent vasodilation, but, because of differences that have been observed between laboratories, we opted for a higher concentration of l-NAME. Our laboratory previously showed that a dose of 5 mM BEC + 5 mM nor-NOHA was sufficient to inhibit arginase in young and old skin (18).

Skin temperature (Tsk) was controlled using a water-perfused suit that covered the entire body except the head, hands, feet, and experimental arm. Copper-constantan thermocouples were placed on the surface of the skin at six different sites (calf, thigh, abdomen, chest, shoulder, and back) to continually monitor Tsk. Each subject's heart rate was monitored throughout the protocol, and arterial blood pressure was measured every 5 min (Cardiocap; GE Healthcare) and verified by brachial auscultation throughout the protocol. Oral temperature (Tor) was measured as an index of changes in body core temperature using a thermistor placed in the sublingual sulcus throughout baseline and whole body heating. Proper placement of the sublingual thermistor was checked and verified based on temperature readings. Once proper placement was verified, the thermistor was taped in place, and subjects were instructed to keep their mouth closed throughout the protocol. Tor was closely monitored throughout heating, and consistency of the probe placement was routinely ensured. Local Tsk over each MD site was maintained at 33°C throughout baseline and whole body heating (Moor Instruments SHO2) to ensure any changes in SkBF were of reflex origin.

To obtain an index of SkBF, cutaneous red blood cell flux was continually measured directly over each experimental site with an integrated laser-Doppler flowmetry probe placed in a local heater (MoorLab, Temperature Monitor SH02; Moor Instruments, Devon, UK). Cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) was calculated as red blood cell flux divided by the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and expressed as a percent of maximum vasodilation [%CVCmax; 28 mM sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and local heat to 43°C]. MAP was calculated as diastolic pressure plus one-third pulse pressure.

Experimental protocol.

After MD fiber placement and the insertion trauma resolution period, baseline data were collected (20 min). Throughout this baseline period, mean Tsk was held at thermoneutral by perfusing 34°C water through the suit. After baseline data were collected, 52°C water was perfused through the suit to clamp mean Tsk at 39°C. At a 1°C rise in Tor, mean body temperature (Tb) was clamped by lowering the temperature of the water perfusing the suit such that mean Tsk and Tor ceased to rise. After 5 min of steady laser-Doppler flux values, 20 mM l-NAME was perfused through each MD fiber at a rate of 4 ìl/min to inhibit NOS production of NO and assess NO-dependent vasodilation within each site. l-NAME perfusion was discontinued after laser-Doppler flux values decreased to a steady plateau (∼40 min). At that time, whole body heating was terminated, the water perfusing the suit was returned to 34°C, and subjects were returned to thermoneutral conditions. After completion of the whole body heating protocol, site-specific pharmacological treatments were discontinued, and 28 mM SNP (Nitropress; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) dissolved in lactated Ringer solution was perfused through each MD fiber at a rate of 4 ìl/min along with simultaneous local heating of the skin to 43°C at each site (∼30 min) to obtain maximal CVC values.

Data acquisition and analysis.

CVC data from the control, BH4, NOS-inhibited, and arginase-inhibited sites were acquired at 40 Hz, digitized, and stored on a personal computer until further data analysis (Windaq; Dataq Instruments, Akron, OH). CVC values were averaged over a 5-min period of stable laser-Doppler flux at baseline, for every 0.1°C rise in Tor during the whole body heating protocol, and over a stable plateau during l-NAME perfusion. Maximal CVC values were averaged over a stable plateau in laser-Doppler flux during perfusion of 28 mM SNP and local heating to 43°C. Mean Tsk was calculated as the unweighted average of the six thermocouple sites, and mean Tb was calculated: Tb = 0.9 Tor + 0.1 Tsk.

NO-dependent vasodilation within each site was assessed at clamped 1°C rise in Tor by quantifying the decrease in CVC observed with complete NOS inhibition (20 mM l-NAME) (NO-dependent vasodilation = CVC at 1°C rise in Tor − CVC plateau with l-NAME infusion). The remaining vasodilation above baseline CVC values following l-NAME perfusion represents NO-independent vasodilation.

Unpaired Student's t-tests were used to detect significant differences between the young and older groups for physical characteristics. A two-way repeated-measures mixed-model ANOVA was used to detect age and local drug differences in NO-dependent vasodilation, and age and drug differences in maximal CVC. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to detect significant differences in Tor, mean Tsk, and mean Tb. A three-way repeated-measures mixed-model ANOVA was conducted to detect age and local drug treatment differences over the rise in Tor (version 9.1.3; SAS, Cary, NC). Post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were performed when necessary to determine where differences between groups and drug treatments occurred. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05 for main effects. Values are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics are presented in Table 1. Age groups were well matched for body mass index, fasting blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and high-density lipoproteins. The older subject group had significantly higher low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and total cholesterol than younger subjects (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Variable | Young | Older |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, M/F | 7,4 | 5,6 |

| Age, yr | 23 ± 1 | 73 ± 2* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25 ± 3 | 26 ± 1 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mg/dl | 89 ± 2 | 95 ± 4 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 72 ± 5 | 105 ± 9* |

| HDL, mg/dl | 53 ± 5 | 61 ± 4 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 142 ± 7 | 182 ± 11* |

| SBP, mmHg | 118 ± 4 | 126 ± 3 |

| DBP, mmHg | 77 ± 3 | 76 ± 2 |

Values are means ± SE for 11 young and 11 older subjects. M, male; F, female; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

P < 0.05, significant difference compared with the young subject group.

Absolute Tor, mean Tsk, and mean Tb at baseline, a 1°C rise in Tor (1°C ΔTor), 20 min into l-NAME treatment (mid-l-NAME), and during the l-NAME plateau are presented in Table 2. Aside from baseline, Tor and Tb were not different between phases or age groups. Tsk was not different between age groups but was significantly different from 1°C ΔTor at baseline, 20 min into l-NAME treatment, and during l-NAME plateau.

Table 2.

Absolute oral temperature, mean skin temperature, and mean body temperature at baseline, 1°C rise in oral temperature, 20 min into l-NAME and during l-NAME plateau

| Baseline | Δ1°C Tor | Mid-l-NAME | l-NAME Plateau | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | ||||

| Tor | 36.6 ± 0.1* | 37.6 ± 0.1 | 37.6 ± 0.1 | 37.7 ± 0.1 |

| Tsk | 34.7 ± 0.2* | 39.0 ± 0.2 | 37.7 ± 0.4* | 37.9 ± 0.3* |

| Tb | 36.4 ± 0.1* | 37.8 ± 0.1 | 37.6 ± 0.1 | 37.7 ± 0.1 |

| Older | ||||

| Tor | 36.7 ± 0.1* | 37.7 ± 0.1 | 37.7 ± 0.1 | 37.7 ± 0.1 |

| Tsk | 35.2 ± 0.2* | 39.4 ± 0.2 | 38.5 ± 0.2* | 38.4 ± 0.2* |

| Tb | 36.5 ± 0.1* | 37.9 ± 0.1 | 37.7 ± 0.1 | 37.8 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± SE for 11 young and 11 older subjects. l-NAME, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; Tor, oral temperature (°C); Tsk, mean skin temperature averaged from 6 sites (calf, thigh, abdomen, chest, shoulder, and back); Tb, mean body temperature (Tb = 0.9 Tor + 0.1 Tsk).

P < 0.05, significant difference from Δ1°C Tor.

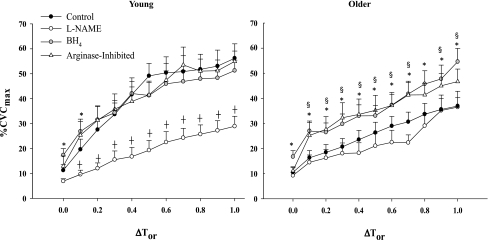

Figure 1 shows vasodilation (%CVCmax) as a function of increasing core temperature (ΔTor) at baseline (ΔTor = 0.0) and during whole body heating at control, NOS-inhibited, BH4-administered, and arginase-inhibited sites in young and older subjects. Compared with young, older subjects exhibited an attenuated vasodilation at the control site beginning at a 0.3°C rise in Tor. When NOS was inhibited throughout the heating protocol (l-NAME site), young and older subjects had similar %CVCmax responses to increased Tor. Local administration of BH4 or local arginase inhibition significantly increased the vasodilation response in older subjects compared with their control site at a 0.1°C rise in Tor. BH4 administration increased baseline %CVCmax in both young (control: 11 ± 2%CVCmax vs. BH4: 17 ± 3%CVCmax, P = 0.029) and older (control: 11 ± 2%CVCmax vs. BH4: 17 ± 2%CVCmax, P = 0.029) subject groups. In the young subject group, there was no longer a difference between BH4-treated sites and control sites beginning at a 0.2°C rise in Tor. Arginase inhibition did not alter baseline %CVCmax in either group.

Fig. 1.

Group mean ± SE of vasodilation [cutaneous vascular conductance expressed as a percent of maximum vasodilation (%CVCmax)] response in young and older subjects to increased core temperature (ΔTor) at baseline (ΔTor = 0.0) and during whole body heating in control, nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-inhibited, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)-treated, and arginase-inhibited sites. Older subjects have an attenuated vasodilation response to increased core temperature compared with young beginning at a 0.3°C rise in Tor. BH4 administration and arginase inhibition increased the vasodilation response in older subjects compared with their control site. BH4 administration increased baseline vasodilation in young and older subjects. *P < 0.05, significant difference between BH4-administered and control sites. †P < 0.05, significant difference between l-NAME and control sites. §P < 0.05, significant difference between arginase-inhibited and control sites.

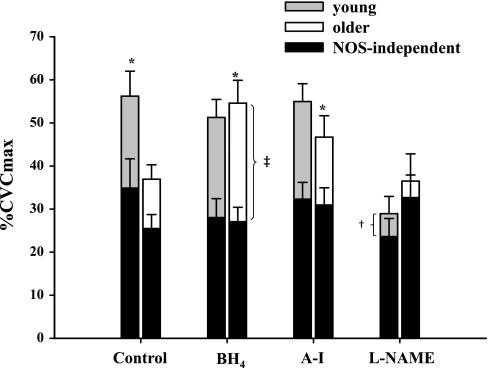

Figure 2 shows the NO-dependent vasodilation (%CVCmax) response at a 1°C rise in Tor at control, BH4-administered, and arginase-inhibited sites in young and older subjects. Compared with the control site of the older subjects, local BH4 administration increased NO-dependent vasodilation (BH4: 32 ± 2% vs. control: 12 ± 2%, P < 0.0001) in the older subject group. Arginase inhibition increased overall vasodilation in older subjects (arginase inhibited: 47 ± 5.0% vs. control, P = 0.002) but did not significantly increase NO-dependent vasodilation. Neither treatment affected the total vasodilator response or NO-dependent vasodilation in the young subject group. Compared with control, NO-dependent vasodilation was significantly attenuated at the l-NAME site in young (l-NAME: 6.4 ± 2% vs. control: 21 ± 4%, P = 0.005) but not older (l-NAME: 3 ± 1% vs. control, P = 0.24) subjects.

Fig. 2.

Group mean ± SE of nitric oxide (NO)-dependent vasodilation (%CVCmax) response in young and older subjects at a 1°C rise in Tor in control, BH4-administered, arginase-inhibited, and NOS-inhibited [NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME)] sites. The complete bars represent the mean response at a 1°C rise in Tor. The black bars represent the mean plateau response after NOS inhibition (l-NAME, 20 mM) within the site at a clamped 1°C rise in Tor. The mean decrease from the peak response to l-NAME plateau represents NO-dependent vasodilation at a 1°C rise in Tor (NO-dependent vasodilation = CVC at 1°C rise in Tor − CVC plateau with l-NAME infusion). BH4 administration increased overall vasodilation and NO-dependent vasodilation in older subjects. Arginase inhibition increased overall vasodilation in older subjects. l-NAME significantly decreased NO-dependent vasodilation in young but not older subjects compared with control. *P < 0.05, significant difference in vasodilation compared with older control. ‡P < 0.05, significant difference in NO-dependent vasodilation compared with older control. †P < 0.05, significant difference from young control.

Table 3 presents maximal CVC values measured at each MD site during combined SNP infusion and 43°C local heating. There was a significant difference between young and old maximal CVC values at the arginase-inhibited site (young: 2.5 ± 0.3 vs. older: 1.5 ± 0.3, P = 0.007), but there were no differences between younger and older subjects in the control, BH4-, or NOS-inhibited sites.

Table 3.

Absolute maximal CVC (sodium nitroprusside perfusion, 28 mM + local heat, 43°C) measured at each intradermal microdialysis site

| Site | Maximal CVC |

|---|---|

| Control young | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| Control older | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| NOS-inhibited young | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| NOS-inhibited older | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| BH4 young | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| BH4 older | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| Arginase-inhibited young | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| Arginase-inhibited older | 1.5 ± 0.3* |

Values are means ± SE. CVC, cutaneous vascular conductance; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; Control, lactated ringer; NOS-inhibited, L-NAME; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin administration. All sites received L-NAME before quantification of maximal CVC.

P < 0.05 compared with young within site.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study was that local BH4 administration increased reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin through NO-dependent mechanisms. In addition, arginase inhibition increased vasodilation to a magnitude similar to that of BH4 through a combination of NO and non-NO-dependent mechanisms. These localized treatments were effective at increasing reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged but not young skin. These data suggest that decreased BH4 may contribute to attenuated reflex vasodilation in aged human skin possibly through limiting NO production through uncoupled NOS. However, BH4 increased vasodilation at baseline in both age groups, which could indicate that a portion of the increased vasodilation in the aged may be due to a baseline shift. Considering the putative role of BH4 in vascular function (5, 6) and the observed restoration of total reflex cutaneous vasodilation during the latter portion of the protocol with significantly elevated body core temperatures, exogenous BH4 administration is a novel potential therapeutic target for augmenting thermoregulatory function in aged humans.

In healthy young subjects, ∼30–40% of the full reflex vasodilation response is mediated by NO signaling with the other ∼60–70% relying on coreleased neurotransmitter(s) with downstream vasodilation mediated through other second messenger pathways and activation of cyclooxygenase (2, 28, 39). With aging, the cofactor-mediated contribution to the overall reflex vasodilation response is attenuated, and COX-dependent signaling favors the production of the vasoconstrictors (12). Consequently, older humans rely on a functionally compromised NO-dependent vasodilation to increase SkBF in the heat (11). In the present study, we have examined the involvement of BH4 in NO-dependent mechanisms because 1) the precise contributions and the identity of the cotransmitters in aged skin is unknown and 2) many of these cotransmitters converge on the NO pathway. Our results suggest that interventions focusing on the NO pathways and specifically BH4 as an essential cofactor are capable of modulating NO synthesis and increasing reflex vasodilation in aged human skin.

NO is synthesized in the cutaneous vasculature by the constitutively expressed NOS isoforms, including endothelial NOS (eNOS) and neuronal NOS (nNOS). Kellogg et al. (23) have reported that NO-dependent reflex vasodilation is mediated exclusively by nNOS in young, healthy subjects. Although specific eNOS inhibitors have not been used to examine the specific contribution of this constitutively expressed isoform on reflex cutaneous vasodilation, BH4 acts as an essential cofactor for both eNOS and nNOS isoforms (34). Thus, NOS is highly dependent on adequate BH4 availability for functional NO synthesis. Furthermore, nNOS is capable of uncoupling and producing superoxide similar to eNOS. Regardless of the precise constitutively expressed NOS isoform mediating the production of NO during reflex vasodilation, our data indicate that local BH4 administration increased NO-dependent dilation and restored the absolute magnitude of reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin.

In the present study, both BH4 administration and arginase inhibition increased vasodilation in the older subject group to a similar magnitude, especially during the later stages of the whole body heating protocol. These data could indicate that 1) these treatments maximized activity through the NOS pathway such that the enzyme was working at or near maximal velocity, and/or 2) we had reached a ceiling effect for the ability of the aged cutaneous vessels to vasodilate. Although both treatments increased reflex vasodilation over control values in the aged, neither treatment fully restored vasodilation to the values seen in young subjects during the earlier stages of the whole body heating protocol (ΔTor = 0.4, 0.5, 0.6°C), possibly illustrating the diminished contribution of cotransmitters. BH4 administration increased NO-dependent vasodilation in aged skin during hyperthermia, resulting in restoration of total reflex cutaneous vasodilation to a similar magnitude as observed in young at a 1°C rise in Tor. Arginase inhibition also increased total reflex cutaneous vasodilation with a 1°C rise in Tor. However, there was significant variability in this response, and, statistically, we were unable to show a significant increase in NO-dependent vasodilation (P = 0.38).

BH4 administration increased baseline vasodilation in both subject groups. During pilot work, we aimed to find a concentration of BH4 that maximized NO-dependent vasodilation while not altering baseline SkBF. However, the concentration of BH4 used in this study modestly increased SkBF during thermoneutral conditions. Considering that BH4 augmented reflex vasodilation in the aged, one potential explanation for these data could be a simple baseline shift. However, with increases in Tor >0.1°C, this increase in %CVCmax disappears in the young subject group. This lack of a continuous upward shift in vasodilation throughout body heating suggests that the differences observed in the aged group are not simply due to a baseline shift.

One alternate explanation for our results is that the augmented reflex cutaneous vasodilation in older subjects at the BH4-administered site is due to the antioxidant properties of BH4 independent of its role in NOS coupling/uncoupling status. Reducing oxidant stress through local supplementation with ascorbate can augment the vasodilatory response in aged skin (16). However, ascorbate has been shown to mediate its effects on vasodilation through its protection and stabilization of the BH4 molecule (19) and through inhibiting arginase activation (36). Thus, direct local administration of BH4 is a more direct way to examine NOS coupling mechanisms.

CVCmax is thought to represent the maximal structural ability of the vessels to vasodilate and is important to assess and present because of the normalization scheme used for presenting the data. Differences in CVCmax are observed in populations where vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy occurs (i.e., essential hypertension) and therefore can greatly affect the interpretation of the data (13, 14). In the context of vascular aging, maximal SkBF is decreased with aging, and this decrease has been systematically investigated in whole limb heating/plethysmography studies (27). In the present study, we were not able to detect this decrease. Furthermore, we have recently done a historical review of our aged cohort from a series of studies over the years and have been unable to detect differences in maximal CVC using measurements from laser-Doppler. This is likely due to the small area of measurement (single-point laser-Doppler) as well as the heterogeneity of the cutaneous microvasculature. Overall, we were unable to detect a main effect for age in maximal CVC across all sites.

Limitations.

We, and others, have used Tor as an index of body core temperature and thermoregulatory drive in studies examining the mechanisms of active cutaneous vasodilation (17, 22, 28, 39). Although esophageal temperature is the gold standard technique for measurement of body core temperature, it was not used in the current study in an effort to minimize subject discomfort. Had we used a thermistor encased in an esophageal probe and placed in the esophagus at the level of the right atrium, we may have obtained more accurate core Tb values during the heating protocol.

In this study, we performed a protocol where we clamped mean Tb and perfused l-NAME through all sites to assess NO-dependent vasodilation. To clamp mean Tb, we decreased the temperature of the water perfusing the suit, uncovered the feet, and unzipped the suit jacket by one-third for some evaporative cooling to take place. Although mean Tb was not significantly different between the end of heating and during the perfusion of l-NAME, the slight changes in Tsk may have resulted in significant changes in efferent cutaneous neural drive. However, this alteration would have been systematic across subjects and does not change our interpretation of the actions of BH4 augmenting NO-dependent vasodilation in the aged.

Older subjects had significantly greater blood total cholesterol and LDL concentrations than young subjects. We have recently demonstrated that increased LDL and specifically oxidized LDL increases arginase activity and limits cutaneous NO-dependent vasodilation (15). These latest data suggest the possibility that the observed effects in the present study may be due to elevated cholesterol and/or LDL. However, the older subject group had LDL and total cholesterol concentrations below 120 and 200 mg/dl, respectively. These values classify the older subject group as nonhypercholesterolemic according to the guidelines set by the American Heart Association. Furthermore, these values are not significantly different from the normocholesterolemic control group used in our previous experiments. However, it remains possible that some of the changes observed with the aged group in respect to attenuated NO-dependent vasodilation may be in part due to increased total and LDL cholesterol.

Perspectives.

Our results suggest that local BH4 administration increases reflex vasodilation in aged skin. In addition, local BH4 administration augments reflex cutaneous vasoconstriction induced by whole body cooling in older subjects through its proposed role as an essential cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase and subsequent norepinephrine synthesis (25). Cumulatively, this series of studies suggests that BH4 may play a dual role in the control of SkBF through its actions as an essential cofactor for monoamine oxidase. Therefore, systemic administration of exogenous BH4 may have positive effects on thermoregulatory function in aged humans provided target tissue concentrations can be increased sufficiently. Oral supplementation with pharmacological preparations of BH4 is a commonly utilized therapy for patients with BH4-responsive phenylketonuria (8). Additionally, oral supplementation with BH4 improves vascular function in animal and human models of vascular dysfunction (3, 33). These data suggest that oral supplementation strategies may be an effective intervention for improved microvascular function in the aged and may expand the range of blood flow responses to both heat and cold in the aged cutaneous vasculature.

In summary, local BH4 administration increases reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin through NO-dependent mechanisms. In addition, arginase inhibition increases vasodilation to a similar magnitude. These localized treatments were effective at increasing reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged but not young skin. These data suggest that decreased BH4 may contribute to attenuated reflex vasodilation in aged human skin possibly through limiting NO production through uncoupled NOS. Considering the putative role of BH4 in vascular function and the observed restoration of total reflex cutaneous vasodilation from the current study, exogenous BH4 administration is a potential therapeutic target for augmenting thermoregulatory function in aged humans.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R01 AG-07004-21.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the assistance of Jane Pierzga, Susan Slimak, Susan Beyerle, Jessica Kutz, and Jessica Dahmus.

Author contributions: A. E. Stanhewicz, data collection, analysis, interpretation and manuscript preparation; R. S. Bruning, data collection and manuscript preparation; C. J. Smith, data collection and manuscript preparation; W. L. Kenney, conceived and designed the research, data interpretation, manuscript preparation, and handled funding and supervision; L. A. Holowatz, conceived and designed the research, data collection, analysis, interpretation and manuscript preparation, handled funding and supervision; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All laboratory work was conducted at Pennsylvania State University.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrew PJ, Mayer B. Enzymatic function of nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovasc Res 43: 521–531, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bennett LA, Johnson JM, Stephens DP, Saad AR, Kellogg DL., Jr Evidence for a role for vasoactive intestinal peptide in active vasodilatation in the cutaneous vasculature of humans. J Physiol 552: 223–232, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cosentino F, Hurlimann D, Delli Gatti C, Chenevard R, Blau N, Alp NJ, Channon KM, Eto M, Lerch P, Enseleit F, Ruschitzka F, Volpe M, Luscher TF, Noll G. Chronic treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin reverses endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolaemia. Heart 94: 487–492, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cosentino F, Luscher TF. Tetrahydrobiopterin and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Cardiovasc Res 43: 274–278, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Delp MD, Behnke BJ, Spier SA, Wu G, Muller-Delp JM. Ageing diminishes endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and tetrahydrobiopterin content in rat skeletal muscle arterioles. J Physiol 586: 1161–1168, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eskurza I, Myerburgh LA, Kahn ZD, Seals DR. Tetrahydrobiopterin augments endothelium-dependent dilatation in sedentary but not in habitually exercising older adults. J Physiol 568: 1057–1065, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grant RH, H Further observations on the vascular responses of the human limb to body warming: evidence for sympathetic vasodilator nerves in the normal subject (Abstract). Clin Sci (Lond) 3: 13, 1938 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guttler F, Lou H, Lykkelund C, Niederwieser A. Combined tetrahydrobiopterin-phenylalanine loading test in the detection of partially defective biopterin synthesis. Eur J Pediatr 142: 126–129, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higashi Y, Sasaki S, Nakagawa K, Kimura M, Noma K, Hara K, Jitsuiki D, Goto C, Oshima T, Chayama K, Yoshizumi M. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves aging-related impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilation through increase in nitric oxide production. Atherosclerosis 186: 390–395, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hodges GJ, Chiu C, Kosiba WA, Zhao K, Johnson JM. The effect of microdialysis needle trauma on cutaneous vascular responses in humans. J Appl Physiol 106: 1112–1118, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holowatz LA, Houghton BL, Wong BJ, Wilkins BW, Harding AW, Kenney WL, Minson CT. Nitric oxide and attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1662–H1667, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holowatz LA, Jennings JD, Lang JA, Kenney WL. Ketorolac alters blood flow during normothermia but not during hyperthermia in middle-aged human skin. J Appl Physiol 107: 1121–1127, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holowatz LA, Kenney WL. Local ascorbate administration augments NO- and non-NO-dependent reflex cutaneous vasodilation in hypertensive humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H109–H1096, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holowatz LA, Kenney WL. Up-regulation of arginase activity contributes to attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilatation in hypertensive humans. J Physiol 581: 863–872, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holowatz LA, Kenney WL. Oral atorvastatin therapy increases nitric oxide-dependent cutaneous vasodilation in humans by decreasing ascorbate-sensitive oxidants. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R763–R768, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holowatz LA, Thompson CS, Kenney WL. Acute ascorbate supplementation alone or combined with arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2965–H2970, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holowatz LA, Thompson CS, Kenney WL. Acute ascorbate supplementation alone or combined with arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2965–H2970, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holowatz LA, Thompson CS, Kenney WL. l-Arginine supplementation or arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilatation in aged human skin. J Physiol 574: 573–581, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang A, Vita JA, Venema RC, Keaney JF., Jr Ascorbic acid enhances endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity by increasing intracellular tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem 275: 17399–17406, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kellogg DL, Jr, Crandall CG, Liu Y, Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 824–829, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kellogg DL, Jr, Pergola PE, Piest KL, Kosiba WA, Crandall CG, Grossmann M, Johnson JM. Cutaneous active vasodilation in humans is mediated by cholinergic nerve cotransmission. Circ Res 77: 1222–1228, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kellogg DL, Jr, Zhao JL, Wu Y. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase control mechanisms in the cutaneous vasculature of humans in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H123–H129, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kellogg DL, Jr, Zhao JL, Wu Y. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase control mechanisms in the cutaneous vasculature of humans in vivo. J Physiol 586: 847–857, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kenney WL, Morgan AL, Farquhar WB, Brooks EM, Pierzga JM, Derr JA. Decreased active vasodilator sensitivity in aged skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H1609–H1614, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lang JA, Holowatz LA, Kenney WL. Local tetrahydrobiopterin administration augments cutaneous vasoconstriction in aged humans. J Physiol 587: 3967–3974, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, Ruiz-Stewart I, Park J, Schulz S, Chepenik KP, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol Rev 52: 375–414, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martin HL, Loomis JL, Kenney WL. Maximal skin vascular conductance in subjects aged 5–85 yr. J Appl Physiol 79: 297–301, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCord GR, Cracowski JL, Minson CT. Prostanoids contribute to cutaneous active vasodilation in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R596–R602, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minson CT, Holowatz LA, Wong BJ, Kenney WL, Wilkins BW. Decreased nitric oxide- and axon reflex-mediated cutaneous vasodilation with age during local heating. J Appl Physiol 93: 1644–1649, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moens AL, Kass DA. Tetrahydrobiopterin and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 2439–2444, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Munzel T, Daiber A, Ullrich V, Mulsch A. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1551–1557, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patrono C, Coller B, Dalen JE, FitzGerald GA, Fuster V, Gent M, Hirsh J, Roth G. Platelet-active drugs: the relationships among dose, effectiveness, and side effects. Chest 119: 39S–63S, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Porkert M, Sher S, Reddy U, Cheema F, Niessner C, Kolm P, Jones DP, Hooper C, Taylor WR, Harrison D, Quyyumi AA. Tetrahydrobiopterin: a novel antihypertensive therapy. J Human Hypertens 22: 401–407, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raman CS, Li H, Martasek P, Kral V, Masters BS, Poulos TL. Crystal structure of constitutive endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a paradigm for pterin function involving a novel metal center. Cell 95: 939–950, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roddie IC, Shepherd JT, Whelan RF. The contribution of constrictor and dilator nerves to the skin vasodilatation during body heating. J Physiol 136: 489–497, 1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santhanam L, Lim HK, Lim HK, Miriel V, Brown T, Patel M, Balanson S, Ryoo S, Anderson M, Irani K, Khanday F, Di Costanzo L, Nyhan D, Hare JM, Christianson DW, Rivers R, Shoukas A, Berkowitz DE. Inducible NO Synthase Dependent S-Nitrosylation and Activation of Arginase1 Contribute to Age-Related Endothelial Dysfunction. Circ Res 101: 692–702, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shastry S, Dietz NM, Halliwill JR, Reed AS, Joyner MJ. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on cutaneous vasodilation during body heating in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 830–834, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Martasek P, Hogg N, Masters BS, Karoui H, Tordo P, Pritchard KA., Jr Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: the influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9220–9225, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wong BJ, Wilkins BW, Minson CT. H1 but not H2 histamine receptor activation contributes to the rise in skin blood flow during whole body heating in humans. J Physiol 560: 941–948, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]