Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important signaling molecule that regulates numerous physiological processes, including activity of respiratory motoneurons. However, molecular mechanism(s) underlying NO modulation of motoneurons remain obscure. Here, we used a combination of in vivo and in vitro recording techniques to examine NO modulation of motoneurons in the hypoglossal motor nucleus (HMN). Microperfusion of diethylamine (DEA; an NO donor) into the HMN of anesthetized adult rats increased genioglossus muscle activity. In the brain slice, whole cell current-clamp recordings from hypoglossal motoneurons showed that exposure to DEA depolarized membrane potential and increased responsiveness to depolarizing current injections. Under voltage-clamp conditions, we found that NO inhibited a Ba2+-sensitive background K+ conductance and activated a Cs+-sensitive hyperpolarization-activated inward current (Ih). When Ih was blocked with Cs+ or ZD-7288, the NO-sensitive K+ conductance exhibited properties similar to TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ (TASK) channels, i.e., voltage independent, resistant to tetraethylammonium and 4-aminopyridine but inhibited by methanandamide. The soluble guanylyl cyclase blocker 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazole(4,3-a)quinoxaline-1-one (ODQ) and the PKG blocker KT-5823 both decreased NO modulation of this TASK-like conductance. To characterize modulation of Ih in relative isolation, we tested effects of NO in the presence of Ba2+ to block TASK channels. Under these conditions, NO activated both the instantaneous (Iinst) and time-dependent (Iss) components of Ih. Interestingly, at more hyperpolarized potentials NO preferentially increased Iinst. The effects of NO on Ih were retained in the presence of ODQ and blocked by the cysteine-specific oxidant N-ethylmaleimide. These results suggest that NO activates hypoglossal motoneurons by cGMP-dependent inhibition of a TASK-like current and S-nitrosylation-dependent activation of Ih.

Keywords: brain slice, genioglossus muscle, hypoglossal motor nucleus, S-nitrosylation

nitric oxide (NO) is a diffusible messenger produced by NO synthase (NOS1–3), and it plays important roles in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological processes (Calabrese et al. 2007). It is well established that soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) is the primary cellular NO receptor; activation of sGC by NO leads to increased cGMP production and subsequent activation of signaling mechanisms including cGMP-dependent protein kinases, phosphodiesterases, and activation of ion channels (Ahern et al. 2002; Garthwaite 2008). In addition, S-nitrosylation has recently emerged as an alternative avenue of NO signaling (Ahern et al. 2002). This cGMP-independent signal is conferred by the covalent addition of an NO moiety to the sulfhydryl group of cysteine residues. This reversible posttranslational modification regulates function of several channels including NMDA receptors (NMDA-R) (Choi et al. 2000), ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels (Kawano et al. 2009), Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (Lang et al. 2000), and cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels (Broillet and Firestein 1996). However, despite compelling evidence that S-nitrosylation is an important component of NO signaling, physiological significance of this pathway remains uncertain.

The hypoglossal motor nucleus (HMN) is an ideal model system to study NO modulation of neuronal activity because 1) properties of hypoglossal motoneurons are well characterized (Rekling et al. 2000); 2) the HMN receives nitrergic innervations (Pose et al. 2005; Travers et al. 2005); 3) hypoglossal motoneurons express sGC (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007); and 4) short-term manipulation of NO/cGMP signaling in the HMN can modulate rhythmic output of the region (Montero et al. 2008). These results provide compelling evidence that NO is an important modulator of hypoglossal motoneuron activity; however, our understanding of the role of NO in the HMN is far from complete. For example, the functional consequence of NO signaling on genioglossus muscle activity has not been described, and mechanism(s) by which acute NO modulates motoneuron activity remain unknown. Studies in hypoglossal and trigeminal motoneurons report that brief (≤10 min) NO exposure depolarized membrane potential with no change in input resistance (Abudara et al. 2002; Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007), suggesting NO has offsetting effects on inward and outward currents. Long-term exposure to NO (hours) leads to motoneuron hyperexcitability by cGMP-dependent inhibition of TASK channels (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007), therefore, a similar mechanism may underlie acute NO responsiveness as well. It also has been proposed that hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels contribute to NO sensitivity of motoneurons (Abudara et al. 2002; Montero et al. 2008); however, this possibility has yet to be demonstrated. HCN channels produce a hyperpolarization-activated inward current (Ih) with two components: a slowly developing steady-state current (Iss) and an instantaneous current (Iinst) (Proenza et al. 2002). It is well known that cyclic nucleotides bind HCN channels to cause a depolarizing shift in Ih activation (Biel et al. 2009; DiFrancesco and Tortora 1991), and evidence suggests that in the heart and other brain regions, NO-mediated cGMP production can activate Ih by this mechanism (Musialek et al. 1997; Pape and Mager 1992; Wilson and Garthwaite 2010). In addition to cyclic nucleotide modulation, it has been shown that HCN channels are targets of endogenous S-nitrosylation (Jaffrey et al. 2001); however, functional evidence supporting this possibility is currently lacking.

Here we show in vitro that NO functions as an excitatory transmitter in the HMN and in vivo that NO signaling in the HMN stimulates genioglossus muscle activity. The molecular mechanisms underling NO sensitivity of hypoglossal motoneurons involves cGMP-dependent inhibition of a TASK-like conductance and activation of Ih by a process consistent with S-nitrosylation. In addition, we find that NO preferentially increased Iinst compared with Iss at more hyperpolarized potentials, suggesting that Iinst can be differentially regulated as a neuromodulatory mechanism.

METHODS

In vivo preparation.

In vivo studies were performed on 9 adult male Wistar rats [mean body weight = 281 ± 6 (SE) g, range = 255–310 g; Charles River]. All procedures conformed to the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, and the University of Toronto Animal Care Committee approved the experimental protocol. The surgical procedures and experimental preparation were similar to those previously described (DuBord et al. 2010).

All experiments were performed under isoflurane anesthesia (2.2–3.1%). After induction of surgical levels of anesthesia, as judged by the abolition of the hindlimb withdrawal and corneal blink reflexes, the rats were tracheotomized and the femoral artery and vein were cannulated. Throughout the surgery and the experiments, the rats spontaneously breathed a 50:50 mixture of room air and oxygen. In all experiments, core body temperature was maintained between 36 and 38°C with a water pump and heating pad (T/Pump heat therapy system; Gaymar, NY). The rats received continuous intravenous fluid (0.4 ml/h) containing 7.6 ml of saline, 2 ml of 5% dextrose, and 0.4 ml of 1 M NaHCO3. For electromyogram (EMG) recordings of diaphragm activity, two insulated, multistranded stainless steel wires (AS636; Coorner Wire, Chatsworth, CA) were sutured into the costal diaphragm via an abdominal approach. The rats were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf model 962; Tujunga, CA), and the head was secured with blunt ear bars. To ensure consistent positioning between rats, the flat skull position was achieved with an alignment tool (Kopf model 944). To record the cortical electroencephalogram (EEG), two stainless steel screws attached to insulated wire were implanted onto the skull over the frontal-parietal cortex (Hajiha et al. 2009). Two stainless steel wire electrodes were also inserted bilaterally under direct observation into the body of the tongue, via an oral approach, to record genioglossus (GG) activity. We have shown that such electrode placements record activity from muscles innervated by the medial branch of the hypoglossal nerve (Morrison et al. 2002).

Microdialysis.

A microdialysis probe (CMA/11 14/01; CSC, St. Laurent, QC, Canada) was placed through a small hole drilled at the junction of the interparietal and occipital bones. The probes were lowered into the HMN at the following final coordinates: 13.7 ± 0.04 mm posterior to bregma, 0.1 ± 0.02 mm lateral to the midline, and 10.1 ± 0.03 mm ventral to bregma. In each rat, a brief burst of GG activity was observed when the probe initially penetrated the HMN, and then the probe was advanced another 0.5 mm before being left at the final coordinates. This burst of GG activity during probe insertion was transient (typically <5 min), did not affect diaphragm activity, blood pressure, or respiratory rate, and was useful as a preliminary indication of probe placement (Hajiha et al. 2009). The rats stabilized for at least 30 min before any interventions, after which the pharmacological interventions were undertaken without changing the level of isoflurane throughout the rest of the study.

The microdialysis probes were 240 μm in diameter with a 1-mm cuprophane membrane and a 6,000-Dalton cutoff. The probes were connected to FEP Teflon tubing (inside diameter = 0.12 mm) and connected to 1.0-ml syringes via a zero-dead space switch (Uniswitch, West Lafayette, IN). The probes were continually flushed with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at a flow rate of 2.0 μl/min using a syringe infusion pump (Pump 22; Harvard Apparatus; Holliston, MA). The lag time for fluid to travel to the tip of the probe at this flow rate was ∼6 min. The composition (in mM) of the ACSF was 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 25, NaHCO3, and 30 glucose. The ACSF was made fresh each day, warmed to 37°C, and bubbled with CO2 to a pH of 7.42 ± 0.01.

Recording.

The electrical signals were amplified and filtered (Super-Z head-stage amplifiers and BMA-400 amplifiers/filters; CWE, Ardmore, PA). The EEG was amplified and filtered between 1 and 100 Hz, whereas the EMG signals were amplified and filtered between 100 and 1,000 Hz. The GG and diaphragm signals were recorded at the same amplification across all experiments. It was not necessary to alter the gain of the recording apparatus between experiments, and baseline EMG activity was similar across rats. The electrocardiogram was removed from the diaphragm signal using an oscilloscope and electronic blanker (model SB-1; CWE). In addition, the moving time averages (time constant = 100 ms) of the GG and diaphragm signals were obtained (Coulbourn S76–01; Lehigh Valley, PA). Each signal, along with blood pressure (DT-XX transducer; Ohmeda, Madison, WI; and PM-1000 amplifier; CWE) were digitized and recorded on computer (Spike 2 software, 1401 interface; CED, Cambridge, UK).

Protocol and analyses.

Signals were recorded continuously during microdialysis perfusion of ACSF into the HMN (control condition) and then during perfusion of the NO donor DEA at 10 and 100 mM. Each intervention lasted 15–25 min. For each agent delivered to the HMN, measurements were taken over 1-min periods at the end of each intervention, i.e., ACSF (baseline control period) and 10 and 100 mM DEA. Breath-by-breath measurements of GG and diaphragm activities were calculated and averaged in consecutive 5-s time bins (Hajiha et al. 2009). All values were written to a spreadsheet and matched to the corresponding intervention at the HMN to provide a grand mean for each variable, for each intervention, in each rat. The EMG signals were analyzed from the moving time average signals (above electrical zero), quantified in arbitrary units, and expressed as a percentage of the respective ACSF controls. Electrical zero was the voltage recorded with the amplifier inputs grounded. GG activity was quantified as mean tonic activity (i.e., basal activity during expiration), peak activity, and respiratory-related activity (i.e., peak inspiratory minus tonic activity). In practice there was no tonic GG activity in these experiments performed under anesthesia, so only respiratory-related GG activity is presented. Mean diaphragm amplitudes (i.e., respiratory-related diaphragm activity), respiratory rate, and mean arterial blood pressure were also calculated for each 5-s period. The EEG was sampled by computer at 500 Hz and subjected to a fast-Fourier transform for each 5-s time bin, and the power within frequency bands spanning the 0.5- to 30-Hz range was calculated. The ratio of high (β2, 20–30 Hz)- to low (δ1, 2–4 Hz)-frequency activity was calculated and used as a relative marker of EEG activation (Hajiha et al. 2009; Steenland et al. 2008). Each rat served as its own control.

Tests of function of HMN and histology.

At the end of each experiment, 10 mM serotonin (creatinine sulfate complex) was applied to the HMN as a positive control to confirm that it was still functional and able to respond to manipulation of neurotransmission as judged by the expected increase in GG activity (Hajiha et al. 2009; Jelev et al. 2001). At the end of each study, the rats were then euthanized under anesthesia by intravenous injection of 3–5 ml of saturated KCl and a high dose of isoflurane. The rats then were perfused intracardially with 0.9% saline and 10% formalin, after which the brain was removed and fixed in 10% formalin. Medullary regions containing the HMN were blocked and transferred to a 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection. The tissue was then sectioned at 50 μm using a cryostat (CM1850; Leica, Nussloch, Germany). Sections were mounted and stained with neutral red, and the lesion sites left by the microdialysis probes were recorded on a corresponding standard cross section using a stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson 1998).

In vitro brain slice preparation.

Slices containing the HMN were prepared as previously described (Sirois et al. 2002). All procedures were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health and University of Connecticut animal care and use guidelines. Briefly, neonatal rats (Sprague-Dawley; 7–12 days postnatal) were decapitated under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia, and transverse brain stem slices (300 μm) were cut using a microslicer (DSK 1500E; Dosaka, Japan) in ice-cold substituted Ringer solution containing (in mM) 260 sucrose, 3 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, and 1 kynurenic acid. Slices were incubated for ∼30 min at 37°C and subsequently at room temperature in normal Ringer solution containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose. Both substituted and normal Ringer solutions were bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2.

Slice-patch electrophysiology.

Individual slices were transferred to a recording chamber mounted on a fixed-stage microscope (Zeiss Axioskop FS) and perfused continuously (∼2 ml/min) with a bath solution composed of (mM) 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose; pH was adjusted to 7.3 by addition of NaOH. Hypoglossal motoneurons were visualized using differential interference optics and identified by their location (lateral and ventrolateral to the central canal) and by their characteristic size and shape (Sirois et al. 2002). All recordings were made with an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier, digitized with a Digidata 1322A analog-to-digital converter, and recorded using pCLAMP 10.0 software (Molecular Devices). Recordings were obtained at room temperature with patch electrodes pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Warner Instruments) on a two-stage puller (P89; Sutter Instruments) to a direct current (DC) resistance of 3–5 MΩ when filled with internal solution containing (in mM) 120 KCH3SO3, 4 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.2% biocytin, and 0.3 GTP-Tris, pH 7.2; electrode tips were coated with Sylgard 184. In current clamp, repetitive firing was evoked from a potential of approximately −60 mV by a series of 1-s depolarizing current pulses of increasing amplitude (Δ10 pA), and the number of evoked spikes was plotted against step current. Depolarizing sag was determined from the difference in membrane potential at the beginning of a −120-pA hyperpolarizing step (i.e., just after the capacitance artifact) and end of the step. Voltage-clamp recordings were made at a holding potential of −60 mV and in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX; 0.1 μM). Exposure to DEA varied between 3- and 5-min durations. We follow the time course of the NO-induced changes in holding current and conductance with intermittent steps (0.2 Hz) to −100 mV. Current-voltage (I-V) relationships were determined for various treatment protocols from “instantaneous” currents (i.e., immediately following the capacitive transient, before activation of the time-dependent Ih current) obtained by hyperpolarizing the cell in 10-mV steps (to −150 mV). We paused for 5–10 s between voltage steps to ensure that currents activated during hyperpolarizing steps have deactivated before the next step as evidenced by superimposed current traces at −60 mV. The maximal amplitude of Ih was quantified as the size of the time-dependent current during a 1-s-long step to −150 mV. The voltage dependence of Ih activation was obtained from tail currents measured at −80 mV following a series of hyperpolarizing steps; those data were normalized and fitted with a Boltzmann function (Sirois et al. 2002). A liquid junction potential of 10 mV was corrected off-line.

Bath NO measurements.

To determine the concentration of NO generated by various concentrations of DEA, we measured NO using a polarographic (+860 mV) electrode (ISO-NOP30; WPI) positioned at a depth of ∼200 μm in the tissue bath. The electrode was calibrated before and after each experiment by decomposition of S-nitroso-N-acetyl-d,l-penicillamine. As shown in Fig. 1A, the concentration of NO increased linearly in response to DEA concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 μM. We also used a mathematical model developed by Schmidt et al. (1997) based on the first-order decomposition of the NO donor (Eq. 1) in association with a third-order reaction of NO with oxygen (Eq. 2) to calculate the concentration of NO generated by ≤20 μM DEA:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where t is time (s), CNO(t) is the concentration of NO at t (M), CD(t) is the concentration of donor at t (M), eNO is the moles of NO released per mole of donor, O2 is the concentration of oxygen (M), k1 is the rate constant for donor decomposition (s−1), and k2 is the rate constant for the oxidation of NO (M−2·s−1). For DEA in aqueous buffer equilibrated with room air at 25°C and pH 7.4, we used the following previously reported values (Schmidt et al. 1997): eNO = 1.4 × 10−3 s−1, k2 = 9.2 × 106 M−2·s−1, and O2 = 2.1 × 10−4 M. The peak NO concentrations generated by 1, 5, 10, and 20 μM DEA were calculated to be 0.5, 1.4, 2.3, and 3.2 μM, respectively. These predicted values are similar to the concentrations of NO measured in our tissue bath during exposure to this range of DEA (Fig. 1, A and B).

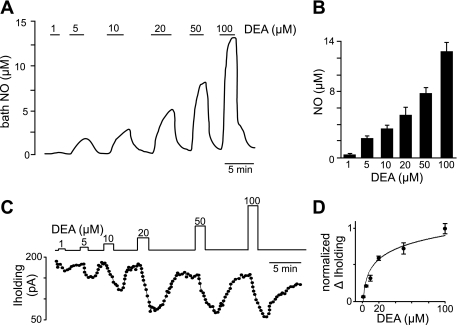

Fig. 1.

Nitric oxide (NO) measurements and estimated diethylamine (DEA) EC50 values of hypoglossal motoneurons in vitro. NO was measured in the tissue bath using a polarographic electrode (+860 mV) with a tip diameter of 30 μm. A trace of NO concentration (A) and summary data (B) show that bath NO concentration increased fairly linearly with increasing concentrations of DEA. C: a trace of holding current (Iholding) from a hypoglossal neuron shows that exposure to this same range of DEA concentrations reversibly decreased holding current. D: average (n = 5) change (Δ) in holding current at each DEA concentration was normalized and plotted as a dose-response curve. The estimated DEA EC50 of hypoglossal motoneurons was ∼18 μM.

To relate NO concentration to cellular responsiveness, we made whole cell voltage-clamp recordings (holding potential = −60 mV; in the presence of TTX) from hypoglossal neurons during exposure to this same range of DEA concentrations (Fig. 1C). The DEA-induced change in holding current was normalized and fit to a single-exponential equation to estimate the DEA EC50 of hypoglossal motoneurons (Fig. 1D). For all slice-patch experiments, we used a DEA concentration of 20 μM, which is near the estimated EC50 of ∼18 μM and similar to DEA concentrations used to manipulate motoneuron activity (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007; Montero et al. 2008).

Statistical analysis.

Data are means ± SE and were analyzed using the paired t-test or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test when appropriate. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

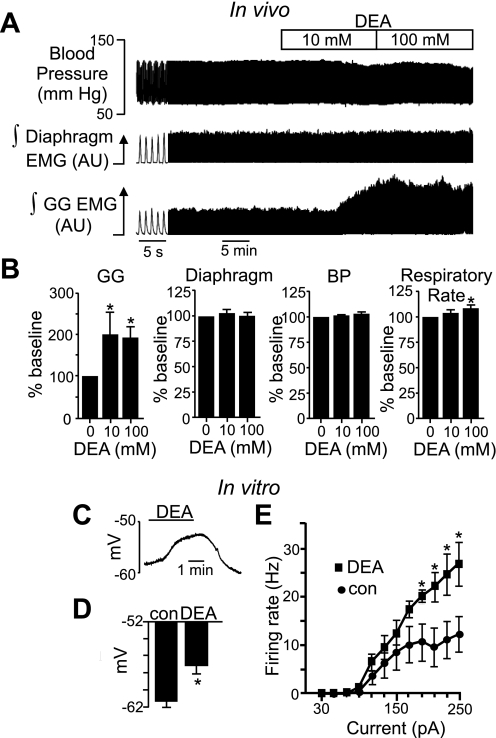

To determine whether NO functions as an excitatory transmitter in the HMN, we tested the functional consequence of NO signaling in the HMN on GG muscle activity in vivo and the effects of DEA on membrane potential of hypoglossal motoneurons in vitro. Microperfusion of DEA (10 mM) into the HMN in vivo caused a robust increase in GG activity with no change in diaphragm activation, blood pressure (Fig. 2, A and B), or EEG activity (not shown). Note that microdialysis typically requires 10–100 times higher drug concentrations than used in vitro because of reduced tissue access and limited drug diffusion across the probe membrane (Steenland et al. 2008). Despite this potential limitation, the effects of DEA described here seem specific to the HMN given that there were no changes in blood pressure, EEG, or diaphragm activity. However, higher concentrations of DEA (100 mM) increased respiratory rate (Fig. 2A), suggesting spillover onto neighboring structures. In the brain slice preparation, exposure to 20 μM DEA, which corresponds with a bath NO concentration of 5.1 ± 0.4 μM (Fig. 1, C and D), depolarized membrane potential (7.1 ± 1 mV; n = 8, in the presence of 0.1 μM TTX to block action potentials) and increased the firing rate response (in TTX-free medium) of hypoglossal motoneurons to depolarizing current injections (Fig. 2, C–E) but with no parallel change in input resistance. We did not observe a change in action potential threshold; however, this is not unexpected considering DEA did not affect input resistance. Decomposed DEA that is no longer able to release NO had no effect (not shown), indicating that effects of DEA on hypoglossal motoneurons are mediated by NO rather than potential reactive by-products. These results are consistent with reported effects of NO on intrinsic excitability of hypoglossal motoneurons (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007; Montero et al. 2008) and suggest that NO sensitivity is mediated by offsetting effects on inward and outward currents.

Fig. 2.

NO functions as an excitatory transmitter in the hypoglossal motor nucleus (HMN) in vitro and in vivo. A: traces of blood pressure (BP) and integrated (∫) diaphragm and genioglossus (GG) electromyogram (EMG) activity show that microperfusion of DEA (10 mM) into the HMN of an anesthetized adult rat doubled respiratory-related GG activity with no change in other parameters of interest. AU, arbitrary units. B: summary of in vivo data (n = 9) showing effects of 10 and 100 mM DEA on GG and diaphragm EMG activity, BP, and respiratory rate. C: slice-patch recording of membrane potential shows that DEA (20 μM) reversibly depolarized membrane potential ∼8 mV. D: summary of in vitro data (n = 7) showing DEA-induced depolarization. con, Control. *P < 0.05. E: steady-state frequency-current relationships under control conditions and in the presence of DEA show that DEA increased the firing rate response to depolarizing current injections greater than +190 pA. *P < 0.05.

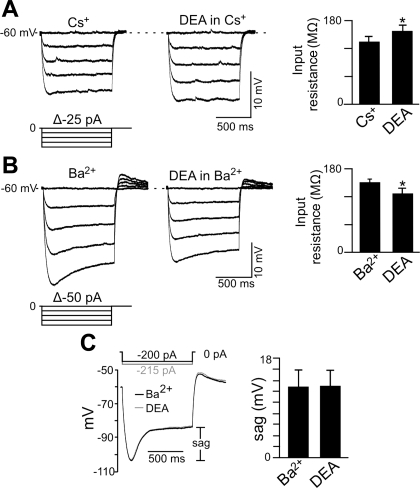

There are several candidate NO-sensitive ion channels in hypoglossal motoneurons, including background K+ channels (e.g., TASK) and HCN channels (Rekling et al. 2000; Sirois et al. 2002). To gain insight into the potential involvement of these channels in NO sensitivity of hypoglossal motoneurons, we made current- and voltage-clamp recordings (holding potential of −60 mV; 0.1 μM TTX) from these cells during exposure to DEA in the presence of Ba2+ (2 mM) to block contributions of background K+ channels (Goldstein et al. 2005) or in the presence of Cs+ (2 mM) to block HCN channels (Biel et al. 2009). In current clamp, application of DEA (20 μM) in the presence of Cs+ depolarized membrane potential 2.3 ± 0.4 mV (n = 6) (not shown) and increased input resistance from 134 ± 12 to 157 ± 12 MΩ (Fig. 3A), suggesting that DEA inhibited a resting K+ conductance. In the presence of Ba2+, application of DEA depolarized membrane potential 6.3 ± 0.5 mV (n = 4) (not shown) and decreased input resistance (measured just after the hyperpolarizing step) from 152 ± 6 to 128 ± 9 MΩ (Fig. 3B). To compare effects of DEA on amplitude of depolarizing sag in membrane potential, we used larger current steps in DEA to match peak hyperpolarizing voltage responses. We found that DEA did not change amplitude of the depolarizing sag during hyperpolarizing current steps (Fig. 3C). It is well established that depolarizing sag is determined by the time-dependent activation of Ih (Bayliss et al. 1994). However, it is possible to increase Ih but with no corresponding increase in depolarizing sag by preferentially increasing Iinst relative to Iss. We explore mechanisms underling NO activation of hypoglossal motoneurons further in the experiments described below.

Fig. 3.

Effects of NO on input resistance and depolarizing sag. A: voltage trajectories in response to hyperpolarizing current steps in Cs+ alone and Cs+ plus DEA show that DEA increased input resistance (i.e., decreased conductance). Summary data (n = 6) plotted as input resistance in response to −100-pA current steps show that when a hyperpolarization-activated inward current (Ih) was blocked with Cs+, DEA increased input resistance, suggesting that NO can inhibit a resting K+ conductance. *P < 0.05. B: voltage trajectories in response to hyperpolarizing current steps in Ba2+ alone and Ba2+ plus DEA show that under these conditions, exposure to DEA decreased input resistance (i.e., increased conductance). Summary data (n = 4) plotted as input resistance in response to −200-pA current steps show that when background K+ channels were blocked with Ba2+, exposure to DEA decreased input resistance. *P < 0.05. Insets in A and B show the protocols delivered from a potential of −60 mV. Note that in both sets of experiments, input resistance was measured shortly after the capacitance artifact. C: superimposed membrane potential responses to hyperpolarizing current injection (−120 pA) in Ba2+ alone and in Ba2+ plus DEA show that DEA caused a decrease in the amplitude of depolarizing sag (measured as the voltage difference shortly after the capacitance artifact and the voltage near the end of the step).

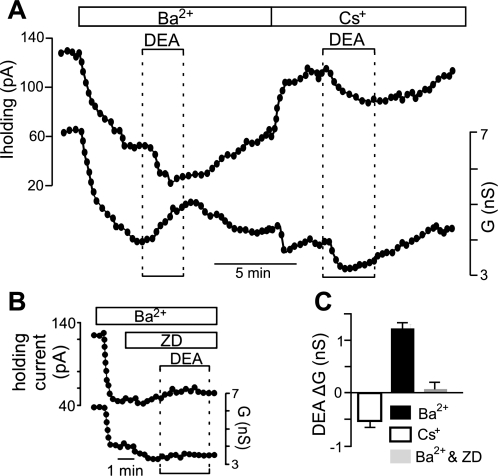

In voltage clamp, exposure to Ba2+ decreased outward current and conductance as expected for inhibition of a resting K+ conductance. In the continued presence of Ba2+, exposure to DEA (20 μM) decreased holding current by 24.8 ± 3.0 pA in conjunction with an increase in conductance of 1.25 ± 0.21 nS (n = 10) (Fig. 4, A and C), suggesting that NO activates an inward current possibly mediated by HCN channels. In a second set of experiments, we replaced Ba2+ with Cs+ (2 mM) to block HCN channels. Under these conditions, exposure to DEA decreased holding current by 35.8 ± 2.4 pA and decreased conductance by 0.95 ± 0.06 nS (n = 25) (Fig. 4, A and C), suggesting that NO may inhibit a K+ conductance. In addition, in the combined presence of Ba2+ and Cs+ or ZD-7288 [50 μM, a potent and selective HCN channel blocker in the low micromolar range, e.g., 10 μM ZD-7288 completely blocked Ih in facial motoneurons (Larkman and Kelly 2001)], exposure to DEA had no effect on holding current or conductance (Fig. 4, B and C). Together, these results indicate that mechanisms underlying NO sensitivity of hypoglossal motoneurons involve inhibition of one or more Ba2+-sensitive K+ channels and activation of a Cs+-sensitive inward current reminiscent of Ih.

Fig. 4.

NO modulation of hypoglossal motoneurons involves activation of an inward Cs+-sensitive current and inhibition of an outward Ba2+-sensitive current. A: traces of holding current (Iholding) and conductance (G) show that Ba2+ (2 mM) decreased holding current and conductance. In the continued presence of Ba2+, exposure to DEA (20 μM) decreased holding current and increased conductance. A second exposure to DEA, this time in Cs+ (2 mM), decreased holding current and conductance. G, conductance. B: in the presence of Ba2+ to block background K+ channels and ZD-7288 (ZD; 50 μM) to block HCN channels, exposure to DEA had no effect on holding current or conductance. C: summary data showing DEA-induced conductance (ΔG) in Ba2+ (n = 10), Cs+ (n = 25), and Ba2+ plus Cs+ or ZD (n = 8). These results suggest that effects of NO on motoneurons involve inhibition of a background K+ channel and activation of a Cs+-sensitive Ih-like current.

Evidence suggests that long-term exposure to NO inhibits a TASK-like conductance in hypoglossal motoneurons (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007); therefore, we considered the possibility that TASK channels also contribute to acute effects of NO. To test this possibility, we characterized effects of K+ channel blockers on the K+ component of the DEA-sensitive current. Inhibition of voltage-gated K+ channels with tetraethylammonium (TEA; 10 mM) or 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 50 μM) had no effect on the DEA-sensitive current in Cs+ (Fig. 5, A–C). Under these conditions, the I-V relationship of the NO-sensitive current is similar to TASK, i.e., relatively voltage independent, active at resting membrane potential and reversed near the equilibrium potential for K+ (Fig. 5B). To confirm that TASK channels contribute to NO sensitivity of hypoglossal neurons, we retested DEA in Cs+, this time in the presence of methanandamide, a blocker of TASK-1, TASK-3, and heteromeric TASK1/3 channels (Kim et al. 2009). Methanandamide (10 μM) decreased the effect of DEA on holding current by 40% and virtually eliminated the residual NO-sensitive current in Cs+ (Fig. 5, D–F). In addition, we found in Cs+ that bath application of the selective sGC blocker 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazole(4,3-a)quinoxaline-1-one (ODQ, 10 μM) decreased effects of DEA on holding current by 62 ± 4% (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the signaling pathway responsible for NO modulation of TASK channels in hypoglossal motoneurons is cGMP dependent. Furthermore, in the presence of Cs+, bath application of the selective PKG blocker KT-5823 (1 μM) also decreased effects of DEA on holding current by 98 ± 5% (Fig. 6B). These results are consistent with long-term effects of NO/cGMP on TASK channels in hypoglossal motoneurons (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007) and suggest that TASK-1 and/or TASK-3 channels are important determinants of NO sensitivity in these cells.

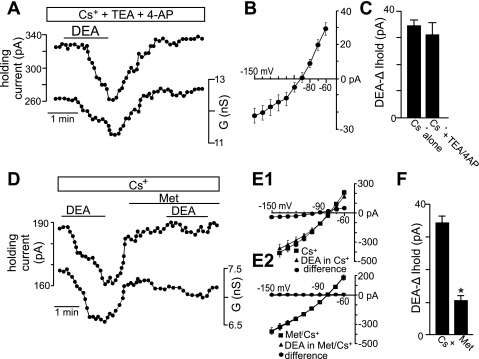

Fig. 5.

NO inhibits a TASK-like current in hypoglossal motoneurons. A: traces of holding current and conductance show that in Cs+ (2 mM) to block hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels and tetraethylammonium (TEA; 10 mM) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 50 μM) to block voltage-gated K+ channels, exposure to DEA (20 μM) decreased outward current and conductance. B: average (n = 6) current-voltage (I-V) relationship of the NO-sensitive current (determined by subtracting I-V relationships obtained during exposure to DEA from those recorded in the absence of DEA) in Cs+ is similar to a TASK-like conductance, i.e., relatively voltage-independent current that is active at resting membrane potential and reverses near the equilibrium potential for K+. C: summary data (n = 6) show DEA-induced changes in holding current in Cs+ alone and in Cs+ with TEA and 4-AP. D: traces of holding current and conductance show that in Cs+, exposure to DEA decreased outward current and conductance. However, responsiveness to a second DEA exposure was reduced by methanandamide (Met; 10 μM), a TASK channel blocker. E1 and E2: average I-V relationships in Cs+ alone and during exposure to DEA in Cs+ with and without Met. F: summary data (n = 6) show that in the continued presence of Cs+, subsequent inhibition of TASK channels with Met decreased the DEA-induced change in holding current. *P < 0.05.

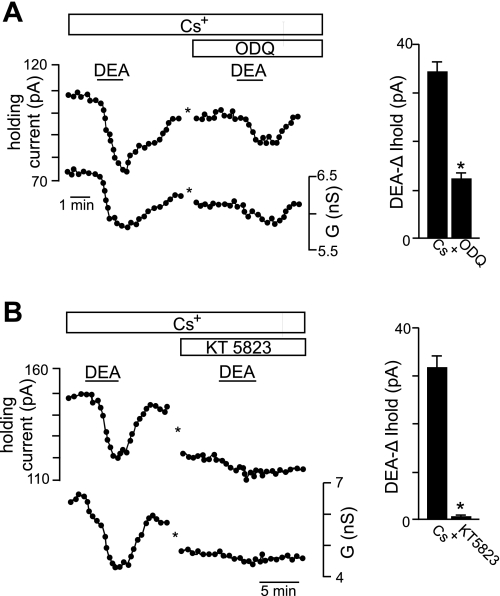

Fig. 6.

NO modulation of TASK channels in hypoglossal motoneurons involves cGMP and PKG. A: traces of holding current and conductance show that when HCN channels were blocked with Cs+ (2 mM), exposure to DEA decreased holding current and conductance by ∼25 pA and ∼0.8 nS, respectively. In the continued presence of Cs+, a second exposure to DEA, this time in the presence of 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazole(4,3-a)quinoxaline-1-one (ODQ; 20 μM), decreased holding current and conductance by only ∼13 pA and ∼0.3 nS, respectively. The asterisks designate a 10-min time break. Right, summary data (n = 13) show that ODQ decreased DEA-sensitivity of the TASK-like conductance. *P < 0.05. B: traces of holding current and conductance show another example where in Cs+, exposure to DEA decreased holding current and conductance by ∼30 pA and ∼2 nS, respectively. A second exposure to DEA in Cs+, this time after ∼4 min of incubation in KT-5823 (1 μM), had negligible effects on holding current or conductance. Right, summary data (n = 4) show that KT-5823 decreased DEA sensitivity of the TASK-like conductance. *P < 0.05.

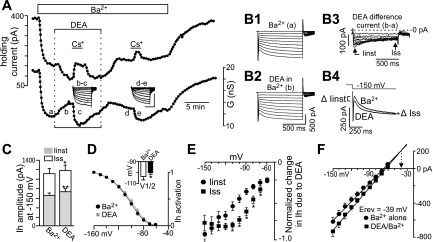

Our evidence also indicates that NO activates an inward current with properties similar to Ih (i.e., strongly inhibited by Cs+ and ZD-7288 but resistant to Ba2+). Therefore, to study NO modulation of native HCN channels in relative isolation, we used Ba2+ (2 mM) to block background K+ channels with minimal effect on HCN channels (Biel et al. 2009). Under these conditions, exposure to DEA (20 μM) decreased holding current by 60.3 ± 3.1 pA and increased conductance by 1.32 ± 0.1 nS (n = 20), indicating that DEA activated an inward current (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the effects of Cs+ on holding current and conductance were 94.7 ± 22% and 75.4 ± 8.3% (n = 9; Fig. 7A) larger in DEA plus Ba2+ compared with Ba2+ alone, indicating that DEA activates a Cs+-sensitive inward current similar to Ih. Interestingly, the DEA difference current (Fig. 7B3), generated by subtracting current responses to hyperpolarizing voltage steps recorded in DEA plus Ba2+ (Fig. 7B2) from those recorded in Ba2+ alone (Fig. 7B1), shows that at more negative potentials, DEA increased Iinst to a greater extent than Iss. This can also be seen in superimposed current trajectories in response to a −150-mV step in Ba2+ alone and DEA plus Ba2+ and in the summary data plotted as amplitude of total Ih at −150 mV (Fig. 7C). We determined the effects of DEA on the voltage dependency of Ih activation by measuring tail currents at a fixed potential of −80 mV after activating Ih with a series of hyperpolarizing voltage steps. Normalized Ih tail currents were plotted as a function of membrane potential during the initial hyperpolarizing steps and fitted with a Boltzmann function to determine the half-activation voltage (V1/2) (Serios et al. 2002). The V1/2 for Ih activation averaged −103.6 ± 3.3 mV in control conditions and −100.3 ± 3.0 mV in DEA; thus DEA caused a small depolarizing shift of ∼3 mV (P < 0.015; n = 5) (Fig. 7D). In addition, the I-V relationships of normalized DEA difference currents measured after the capacitance artifact (Iinst) and at the end of the voltage step (Iss) show that DEA increased Iinst but blunted inward rectification of Iss to the extent that amplitude of Iinst at −150 mV was greater than that of Iss (Fig. 7E). To confirm that DEA activates the instantaneous component of Ih, we used established protocols to estimate the reversal potential of Iinst (Bayliss et al. 1994; Mayer and Westbrook 1983) under control conditions and in the presence of DEA. The Iinst was measured immediately following the capacitive transient and plotted against membrane potential at the same time point and fitted with linear regression. The point of intersection between these regression lines represents the reversal potential of the instantaneous current activated by DEA. As shown in Fig. 7F, DEA increased slope conductance, and the extrapolated intersection is near the predicted reversal potential for Ih (−39 mV). These results suggest that the instantaneous current activated by DEA is Ih.

Fig. 7.

NO increases the instantaneous (Iinst) and time-dependent (Iss) components of Ih. A: traces of holding current and conductance show that in Ba2+ (2 mM) to block background K+ channels, exposure to DEA (20 μM) decreased outward current and increased conductance. In addition, DEA increased effects of Cs+ on holding current and conductance by 55% and 58% (n = 9), indicating that DEA increased a Cs+-sensitive inward current. Inset: Cs+-sensitive difference currents, generated by subtracting current responses to hyperpolarizing voltage steps recorded at the indicated times a–e (scale bars are 500 ms and 500 pA). B1–B3: current responses to hyperpolarizing voltage steps recorded in Ba2+ alone (B1), Ba2+ plus DEA (B2), and the corresponding difference current (B3) show that DEA increased both Iinst and Iss, but at more hyperpolarized potentials NO increased Iinst to a greater extent than Iss. This can also be seen in superimposed current responses to a −150-mV step in Ba2+ alone and Ba2+ plus DEA (B4). C: average Ih amplitude plotted as Iinst and Iss evoked by a −150-mV step in Ba2+ alone (n = 8) and Ba2+ plus DEA (n = 8). *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.001. D: Ih activation curves in Ba2+ alone and in Ba2+ plus DEA. Inset: DEA caused a small (3 mV) depolarizing shift in Ih activation. E: average (n = 8) I-V relationships of the NO-sensitive Iinst and Iss currents. *P ≤ 0.05. ‡P < 0.05 designates the potential at which Iinst is greater than Iss. F: average (n = 8) I-V relationships of Iinst in Ba2+ alone and in Ba2+ plus DEA. The data were fitted with linear regression, and the extrapolated intersection of the regression lines is near the reversal potential (Erev) for Ih.

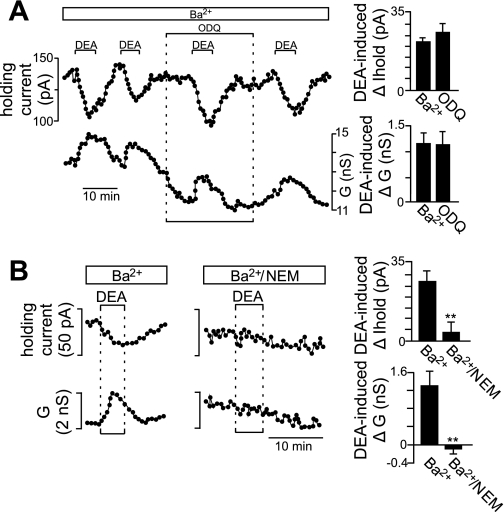

The observed effects of DEA on HCN channels differ from the well-known effects of cyclic nucleotides on Ih (DiFrancesco and Tortora 1991); suggesting this novel form of HCN channel modulation is conferred by S-nitrosylation. Consistent with this possibility, we found that effects of DEA (in Ba2+) on holding current and conductance were fully retained when activity of sGC was blocked with ODQ (20 μM) (Fig. 8A). There are no selective blockers of S-nitrosylation signaling; however, this is a reduction-oxidation reaction that requires the thiol group of cysteine residues to be in the reduced state. Therefore, we used the cysteine-specific oxidant N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; 300 μM) to oxidize cysteine residues and thus occlude subsequent S-nitrosylation. Exposure to NEM decreased holding current and conductance by 82.77 ± 14.6 pA (n = 6) and 2.63 ± 0.57 nS (n = 6), respectively. In NEM, the DEA-induced inward current was reduced by 92.7 ± 11.0% (Fig. 8B), suggesting that NO modulates HCN channels by an S-nitrosylation-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 8.

NO modulates HCN channels by an S-nitrosylation-dependent mechanism. A: traces of holding current and conductance show that exposure to DEA in Ba2+ (2 mM) activated an inward current with properties similar to Ih (Figs. 3 and 5). Inhibition of soluble guanylyl cyclase with ODQ (10 μM) did not affect NO modulation of Ih. Bar graphs at right show summary data (n = 6) plotted as DEA-induced changes in holding current and conductance in Ba2+ alone and in Ba2+ plus ODQ. B: traces of holding current and conductance show the characteristic DEA response in Ba2+. A second exposure to DEA after incubation in the cysteine-specific oxidant N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; 300 μM) this time had little effect on holding current or conductance. Bar graphs at right show summary data (n = 5) plotted as DEA-induced changes in holding current and conductance in Ba2+ alone and in Ba2+ plus NEM. Together, these results strongly support the possibility that NO activates Ih by a S-nitrosylation-dependent mechanism.

DISCUSSION

Nitric oxide regulates numerous physiological processes, including rhythmic activity of respiratory motoneurons. However, molecular mechanism(s) underlying NO sensitivity of respiratory motoneurons is not known. Here, we have shown that NO targeted two different types of ion channels in hypoglossal motoneurons (background TASK channels and HCN channels) and modulated them in opposite directions by two distinct signaling pathways: NO inhibited TASK channels by a cGMP-dependent mechanism and activated HCN channels by what appears to be an S-nitrosylation-dependent mechanism. In contrast to the well-known effects of cyclic nucleotides on HCN channels (DiFrancesco and Tortora 1991), we found that modulation by S-nitrosylation increased Iinst to a greater extent then Iss at more hyperpolarized potentials, suggesting that Iinst can be differentially regulated by NO. In addition, when TASK and HCN channels were blocked, exposure to NO had no effect on holding current or conductance. These results identify TASK and HCN channels as likely molecular substrates responsible for NO modulation of hypoglossal motoneurons.

It is well established that NO can modulate synaptic activity (Prast and Philippu 2001); therefore, we performed all voltage-clamp experiments in the presence of TTX to block action potentials and thus Ca2+-dependent transmitter release. However, it is possible that NO may increase spontaneous release of neurotransmitters. For example, NO has been shown to increase Ca2+-independent synaptic release (Meffert et al. 1994), and conceivably this effect would be retained in the presence of TTX. However, we did not observe an increase in miniature postsynaptic potentials during DEA application, and our results are consistent with previous evidence that NO modulates intrinsic excitability of hypoglossal motoneurons even in the presence of a cocktail of synaptic blockers (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007; Montero et al. 2008). Therefore, these results suggest that NO effects are, at least in part, independent of synaptic transmission. Another limitation of our experimental approach is that exogenous application of 20 μM DEA does not exactly mimic endogenous production of NO by NOS1-expressing terminals in the HMN. Nevertheless, the concentration of DEA used here is near the EC50 for hypoglossal motoneurons and similar to those required to mimic endogenous NO effects on intrinsic excitability of hypoglossal motoneurons (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007), and so we consider it a reasonable approximation of physiological NO concentration.

NO/cGMP signaling inhibits a TASK-like current in hypoglossal motoneurons.

Evidence indicates that acute NO exposure depolarized membrane potential of brain stem motoneurons without corresponding changes in input resistance (Abudara et al. 2002; Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007), suggesting that NO affects multiple channels with offsetting effects on net whole cell conductance. Although the majority of outward-directed K+ channels are activated by NO (e.g., KATP and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels), there is evidence that NO/cGMP can inhibit TASK channels (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007). Evidence also suggests that NO can activate HCN channels to increase inward-directed Ih (Musialek et al. 1997; Wilson and Garthwaite 2010). To study effects of NO on K+ currents in the absence of contamination by Ih, we used Cs+ or ZD-7288 to block HCN channels. Under these conditions, we detected an NO-sensitive K+ conductance that was voltage independent, active at resting membrane potential, and resistant to TEA or 4-AP but inhibited by methanandamide. These properties are most consistent with TASK channels. However, it should be noted that bath application of Cs+ can also block inward-rectifying K+ (Kir) channels (Hagiwara et al. 1976); therefore, it remains possible that Kir channels in addition to TASK may also contribute to NO modulation of hypoglossal motoneurons. In addition to TASK, several other members of the KCNK family of background K+ channels are modulated by NO, including TREK-1 (Koh et al. 2001) and TALK-1 and -2 (Duprat et al. 2005). However, of these, only TASK-1 and TASK-3 channel subunits appear to be expressed by hypoglossal motoneurons, where they have been shown to form heterodimeric channels that produce the majority of background K+ conductance in these cells (Berg et al. 2004). Therefore, NO-mediated inhibition of TASK likely contributes to membrane depolarization and increased excitability.

We found that NO sensitivity of this TASK-like current was blunted by inhibition of sGC and PKG, suggesting NO modulates TASK channels by cGMP-dependent activation of PKG. These results are consistent with long-term effects of NO on TASK channels in hypoglossal motoneurons (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007). However, these results are not consistent with evidence that PKG activates TASK-1 channels in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (Toyoda et al. 2010). These disparate results may be explained by the likelihood that heteromeric TASK1/TASK3 channels in hypoglossal motoneurons have properties distinct from homomeric TASK-1 channels in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons.

NO activates Ih by a mechanism consistent with S-nitrosylation.

HCN channels (HCN1–4) are members of the subgroup of cyclic nucleotide-regulated cation channels and function as the molecular correlate of Ih. It is well documented that cAMP can bind HCN channels to cause a depolarizing shift in Ih (DiFrancesco and Tortora 1991). This cAMP-dependent modulation of Ih is crucially important for rhythmic activity of pacemaker cells in the heart and spontaneous activity of certain neurons. However, it is less clear whether NO-mediated increase of cGMP works in a similar fashion to increase Ih or, alternatively, whether NO activates Ih by a cGMP-independent mechanism involving S-nitrosylation. It has been shown that cGMP can bind HCN channels and cause a depolarizing shift in Ih gating; however, the affinity of HCN channels for cGMP is ∼30-fold lower than cAMP (Zagotta et al. 2003). Nevertheless, there is some evidence in the brain and heart that NO/cGMP signaling increases Ih. For example, studies in trigeminal motoneurons and deep cerebellar neurons showed that NO facilitated an Ih-dependent depolarizing sag in the voltage response to hyperpolarizing current injection (Abudara et al. 2002; Wilson and Garthwaite 2010); in cardiac pacemaker cells, NO and a cell-permeable nonhydrolyzable cGMP analog (8-BrcGMP) stimulated heart rate by activation of a Cs+-sensitive current similar to Ih (Musialek et al. 1997); and in thalamocortical neurons, NO activated Ih, and this response was mimicked by 8-BrcGMP (Pape and Mager 1992). These results suggest that NO/cGMP can modulate HCN channels; however, this does not exclude the possibility that HCN channels can also be modulated by S-nitrosylation signaling.

To explore NO modulation of HCN channels in hypoglossal motoneurons, which express HCN1 and HCN2 and a prominent Ih (Chen et al. 2005, 2009), in relative isolation we blocked background TASK channels with high concentrations of Ba2+. Under these conditions, we found that NO activated Ih by a cGMP-independent process, whereas incubation in NEM, which oxidizes sulfhydryl groups, rendering them resistant to S-nitrosylation, blocked effects of NO on Ih. These results suggest that, in addition to the potential cGMP-dependent effects described above, HCN channels (e.g., HCN1 and/or HCN2) may also be modulated by S-nitrosylation. Considering that HCN2 but not HCN1 channels are strongly activated by cyclic nucleotides, it is possible that the observed cGMP-independent modulation of Ih in hypoglossal motoneurons reflects an HCN1-specific effect; however, there are no HCN subunit-specific blockers, so this possibility has yet to be elucidated. Our results provide functional support for the possibility that HCN channels are neural substrates for S-nitrosylation (Jaffrey et al. 2001). These results are also consistent with reported effects of cGMP and S-nitrosylation on structurally related cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (Broillet and Firestein 1996), thus further suggesting that cGMP and S-nitrosylation can function in parallel to independently modulate the same target protein. In addition, we found that NO increased both the instantaneous and time-dependent components of Ih; however, surprisingly, at more negative potentials NO preferentially increased Iinst compared with Iss. These results are consistent with current-clamp evidence suggesting that when background K+ channels were blocked with Ba2+, exposure to NO decreased input resistance (i.e., increased conductance) but with no corresponding change in the amplitude of depolarizing sag. Considering that depolarizing sag reflects the difference between instantaneous and steady-state Ih, it is possible that the preferential activation of Iinst by DEA offset the contribution of the time-dependent component of Ih to sag. This finding differs from a study in thalamocortical neurons where the NO donor SIN1 activated Iss with little effect on Iinst (Pape and Mager 1992). However, it should be noted that SIN1 produces superoxide as a by-product, which may oxidize cysteine residues (Thomas et al. 2002) and occlude the potential contribution of S-nitrosylation. These results may represent the first evidence that NO can change HCN channel activity by selectively enhancing instantaneous Ih. Activation of Ih can depolarize resting membrane potential and increase the firing rate response to depolarizing current injections (Mccaferri and McBain 1996). Therefore, activation of Ih likely contributes to the excitatory effects of NO on hypoglossal motoneurons.

To identify potential S-nitrosylation sites in HCN1 and HCN2, we compiled a list of 898 unique S-nitrosylation sites in mouse and used the motif-x and scan-x algorithms (Schwartz and Gygi 2005;Schwartz et al. 2009) to extract common S-nitrosylation motifs and corresponding position weight matrices. These position weight matrices were then used to scan the protein sequences with positions scoring better than 50% of known mouse S-nitrosylation sites being deemed potential modification sites. The most probable S-nitrosylation site in HCN1 was predicted to be at Cys531 in the COOH-terminal region and in HCN2 at Cys341 in the cytoplasmic loop between S4 and S5. Notably, the putative S-nitrosylation site in HCN2 is near a basic residue (Arg339) that is important for voltage-dependent channel gating; mutations in Arg339 prevented normal channel closure and increased Iinst (Decher et al. 2004). In light of these results and our evidence that S-nitrosylation preferentially increased Iinst at more negative potentials, we hypothesize that S-nitrosylation of Cys341 stabilizes the channel's open state. However, this possibility requires further investigation using recombinant channels expressed in a heterologous expression system.

Physiological significance.

The HMN controls GG muscle activity and is important for a variety of physiological functions including maintenance of airway patency, mastication, and swallowing. It has been known for more than a decade that the HMN receives nitrergic innervation (Pose et al. 2005; Travers et al. 2005), yet potential involvement of NO in HMN function remains obscure because there is limited evidence describing effects of NO on HMN activity in vivo. A study by Montero et al. (2008) showed that microiontophoretic application of an NOS inhibitor or ODQ decreased inspiratory-related HMN activity, whereas injection of DEA or 8-BrcGMP did the opposite. These results are consistent with our evidence that microperfusion of DEA into the HMN increased GG activity, and together these results indicate that NO can influence activity and function of the HMN in vivo. These results suggest that loss of nitrergic drive to the HMN may decrease HMN activity and result in a loss of airway patency. On the other hand, excessive production of NO, as associated with degenerative disorders or injury, may lead to excitotoxicity and motoneuron degeneration (Gonzalez-Forero et al. 2007; Montero et al. 2010; Moreno-Lopez and Gonzalez-Forero 2006; Moreno-Lopez et al. 2011). Therefore, NO/cGMP and S-nitrosylation may represent new avenues for the treatment of pathological conditions resulting from loss of HMN control.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funds from National Institutes of Health Grant HL104101 (to D. K. Mulkey) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MT-15563. R. L. Horner is supported by a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Sleep and Respiratory Neurobiology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: I.C.W., J.P.B., and H.L. performed experiments; I.C.W., J.P.B., X.C., and R.L.H. analyzed data; I.C.W., X.C., R.L.H., and D.K.M. prepared figures; I.C.W., J.P.B., X.C., H.L., R.L.H., and D.K.M. approved final version of manuscript; R.L.H. and D.K.M. interpreted results of experiments; D.K.M. conception and design of research; D.K.M. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Daniel Schwartz for help in identifying potential S-nitrosylation sites in HCN channels.

REFERENCES

- Abudara V, Alvarez AF, Chase MH, Morales FR. Nitric oxide as an anterograde neurotransmitter in the trigeminal motor pool. J Neurophysiol 88: 497–506, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern GP, Klyachko VA, Jackson MB. cGMP and S-nitrosylation: two routes for modulation of neuronal excitability by NO. Trends Neurosci 25: 510–517, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss DA, Viana F, Bellingham MC, Berger AJ. Characteristics and postnatal development of a hyperpolarization-activated inward current in rat hypoglossal motoneurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 71: 119–128, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AP, Talley EM, Manger JP, Bayliss DA. Motoneurons express heteromeric TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ (TASK) channels containing TASK-1 (KCNK3) and TASK-3 (KCNK9) subunits. J Neurosci 24: 6693–6702, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, Wahl-Schott C, Michalakis S, Zong X. Hyperpolarization-activated cation channels: from genes to function. Physiol Rev 89: 847–885, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broillet MC, Firestein S. Direct activation of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel through modification of sulfhydryl groups by NO compounds. Neuron 16: 377–385, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Mancuso C, Calvani M, Rizzarelli E, Butterfield DA, Stella AM. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 766–775, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Shu S, Kennedy DP, Willcox SC, Bayliss DA. Subunit-specific effects of isoflurane on neuronal Ih in HCN1 knockout mice. J Neurophysiol 101: 129–140, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Sirois JE, Lei Q, Talley EM, Lynch C, 3rd, Bayliss DA. HCN subunit-specific and cAMP-modulated effects of anesthetics on neuronal pacemaker currents. J Neurosci 25: 5803–5814, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YB, Tenneti L, Le DA, Ortiz J, Bai G, Chen HS, Lipton SA. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor-coupled ion channel modulation by S-nitrosylation. Nat Neurosci 3: 15–21, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decher N, Chen J, Sanguinetti MC. Voltage-dependent gating of hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated pacemaker channels: molecular coupling between the S4–S5 and C-linkers. J Biol Chem 279: 13859–13865, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D, Tortora P. Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intracellular cyclic AMP. Nature 351: 145–147, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBord MA, Liu H, Horner RL. Protein kinase A activators produce a short-term, but not long-term, increase in respiratory-drive transmission at the hypoglossal motor nucleus in vivo. Neurosci Lett 486: 14–18, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprat F, Girard C, Jarretou G, Lazdunski M. Pancreatic two P domain K+ channels TALK-1 and TALK-2 are activated by nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 562: 235–244, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J. Concepts of neural nitric oxide-mediated transmission. Eur J Neurosci 27: 2783–2802, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SA, Bayliss DA, Kim D, Lesage F, Plant LD, Rajan S. International Union of Pharmacology. LV Nomenclature and molecular relationships of two-P potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 527–540, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Forero D, Portillo F, Gomez L, Montero F, Kasparov S, Moreno-Lopez B. Inhibition of resting potassium conductances by long-term activation of the NO/cGMP/protein kinase G pathway: a new mechanism regulating neuronal excitability. J Neurosci 27: 6302–6312, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S, Miyazaki S, Rosenthal NP. Potassium current and the effect of cesium on this current during anomalous rectification of the egg cell membrane of a starfish. J Gen Physiol 67: 621–638, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajiha M, DuBord MA, Liu H, Horner RL. Opioid receptor mechanisms at the hypoglossal motor pool and effects on tongue muscle activity in vivo. J Physiol 587: 2677–2692, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol 3: 193–197, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelev A, Sood S, Liu H, Nolan P, Horner RL. Microdialysis perfusion of 5-HT into the hypoglossal motor nucleus differentially modulates genioglossus activity across natural sleep-wake states in rats. J Physiol 532: 467–481, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Zoga V, Kimura M, Liang MY, Wu HE, Gemes G, McCallum JB, Kwok WM, Hogan QH, Sarantopoulos CD. Nitric oxide activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in mammalian sensory neurons: action by direct S-nitrosylation. Mol Pain 5: 12, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Cavanaugh EJ, Kim I, Carroll JL. Heteromeric TASK-1/TASK-3 is the major oxygen-sensitive background K+ channel in rat carotid body glomus cells. J Physiol 587: 2963–2975, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Monaghan K, Sergeant GP, Ro S, Walker RL, Sanders KM, Horowitz B. TREK-1 regulation by nitric oxide and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. An essential role in smooth muscle inhibitory neurotransmission. J Biol Chem 276: 44338–44346, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RJ, Harvey JR, McPhee GJ, Klemm MF. Nitric oxide and thiol reagent modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels in myocytes of the guinea-pig taenia caeci. J Physiol 525: 363–376, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkman PM, Kelly JS. Modulation of the hyperpolarisation-activated current, Ih, in rat facial motoneurones in vitro by ZD-7288. Neuropharmacology 40: 1058–1072, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. A voltage-clamp analysis of inward (anomalous) rectification in mouse spinal sensory ganglion neurones. J Physiol 340:19–45, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccaferri G, McBain CJ. The hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) and its contribution to pacemaker activity in rat CA1 hippocampal stratum oriens-alveus interneurones. J Physiol 479: 119–130, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffert MK, Premack BA, Schulman H. Nitric oxide stimulates Ca2+-independent synaptic vesicle release. Neuron 12: 1235–1244, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero F, Portillo F, Gonzalez-Forero D, Moreno-Lopez B. The nitric oxide/cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway modulates the inspiratory-related activity of hypoglossal motoneurons in the adult rat. Eur J Neurosci 28: 107–116, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero F, Sunico CR, Liu B, Paton JF, Kasparov S, Moreno-Lopez B. Transgenic neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression induces axotomy-like changes in adult motoneurons. J Physiol 588: 3425–3443, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Lopez B, Gonzalez-Forero D. Nitric oxide and synaptic dynamics in the adult brain: physiopathological aspects. Rev Neurosci 17: 309–357, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Lopez B, Sunico CR, Gonzalez-Forero D. NO orchestrates the loss of synaptic boutons from adult “sick” motoneurons: modeling a molecular mechanism. Mol Neurobiol 43: 41–66, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JL, Sood S, Liu X, Liu H, Park E, Nolan P, Horner RL. Glycine at the hypoglossal motor nucleus: genioglossus activity, CO2 responses and the additive effect of GABA. J Appl Physiol 93: 1786–1796, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musialek P, Lei M, Brown HF, Paterson DJ, Casadei B. Nitric oxide can increase heart rate by stimulating the hyperpolarization-activated inward current, If. Circ Res 81: 60–68, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC, Mager R. Nitric oxide controls oscillatory activity in thalamocortical neurons. Neuron 9: 441–448, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (4th ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Pose I, Fung S, Sampogna S, Chase MH, Morales FR. Nitrergic innervation of trigeminal and hypoglossal motoneurons in the cat. Brain Res 1041: 29–37, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prast H, Philippu A. Nitric oxide as modulator of neuronal function. Prog Neurobiol 64: 51–68, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proenza C, Angoli D, Agranovich E, Macri V, Accili EA. Pacemaker channels produce an instantaneous current. J Biol Chem 277: 5101–5109, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekling JC, Funk GD, Bayliss DA, Dong XW, Feldman JL. Synaptic control of motoneuronal excitability. Physiol Rev 80: 767–852, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K, Desch W, Klatt P, Kukovetz WR, Mayer B. Release of nitric oxide from donors with known half-life: a mathematical model for calculating nitric oxide concentrations in aerobic solutions. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 355: 457–462, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Chou MF, Church GM. Predicting protein post-translational modifications using meta-analysis of proteome scale data sets. Mol Cell Proteomics 8: 365–379, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Gygi SP. An iterative statistical approach to the identification of protein phosphorylation motifs from large-scale data sets. Nat Biotechnol 23: 1391–1398, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirois JE, Lynch C, III, Bayliss DA. Convergent and reciprocal modulation of a leak K+ current and Ih by an inhalational anaesthetic and neurotransmitters in rat brainstem motoneurones. J Physiol 541: 717–729, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland HW, Liu H, Horner RL. Endogenous glutamatergic control of rhythmically active mammalian respiratory motoneurons in vivo. J Neurosci 28: 6826–6835, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DD, Miranda KM, Espey MG, Citrin D, Jourd'heuil D, Paolocci N, Hewett SJ, Colton CA, Grisham MB, Feelisch M, Wink DA. Guide for the use of nitric oxide (NO) donors as probes of the chemistry of NO and related redox species in biological systems. Methods Enzymol 359: 84–105, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda H, Saito M, Okazawa M, Hirao K, Sato H, Abe H, Takada K, Funabiki K, Takada M, Kaneko T, Kang Y. Protein kinase G dynamically modulates TASK1-mediated leak K+ currents in cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain. J Neurosci 30: 5677–5689, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB, Yoo JE, Chandran R, Herman K, Travers SP. Neurotransmitter phenotypes of intermediate zone reticular formation projections to the motor trigeminal, and hypoglossal nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol 488: 28–47, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GW, Garthwaite J. Hyperpolarization-activated ion channels as targets for nitric oxide signalling in deep cerebellar nuclei. Eur J Neurosci 31: 1935–1945, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagotta WN, Olivier NB, Black KD, Young EC, Olson R, Gouaux E. Structural basis for modulation and agonist specificity of HCN pacemaker channels. Nature 425: 200–205, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]