Abstract

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) play important roles during immune responses to bacterial pathogens. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) regulates extracellular concentrations of ROS/RNS and contributes to tissue protection during inflammatory insults. The participation of ecSOD in immune responses seems therefore intuitive, yet is poorly understood. In the present study, we utilized mice with varying levels of ecSOD activity to investigate the involvement of this enzyme in immune responses against Listeria monocytogenes. Surprisingly, our data demonstrate that, despite enhanced neutrophil recruitment to the liver, ecSOD activity negatively impacted host survival and bacterial clearance. Increased ecSOD activity was accompanied by decreased co-localization of neutrophils with bacteria, as well as increased neutrophil apoptosis, which reduced overall and neutrophil-specific TNF-α production. Liver leukocytes from mice lacking ecSOD produced equivalent nitric oxide (NO·) when compared to mice expressing ecSOD. However, during infection, there were higher levels of peroxynitrite (NO3·−) in livers from mice lacking ecSOD compared to mice expressing ecSOD. Neutrophil depletion studies revealed that high levels of ecSOD activity resulted in neutrophils with limited protective capacity, whereas neutrophils from mice lacking ecSOD provided superior protection compared to neutrophils from wild-type mice. Taken together, our data demonstrate that ecSOD activity reduces innate immune responses during bacterial infection and provides a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) represent a first-line of defense against microbial invasion and replication, but can also cause collateral tissue damage. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) is the only enzyme that mediates the conversion of superoxide (O2·−) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of tissues (1). In this capacity, ecSOD is a potent anti-oxidant that can protect tissues from oxidative damage by regulating various ROS/RNS. H2O2 is also an important bactericidal agent and the precursor for hypochlorous acid, a major component of bleach. It, therefore, seems logical that ecSOD may contribute to pathogen clearance during acute infection.

Surprisingly, the role of ecSOD in immune responses and clearance of pathogens has not been investigated. There are conflicting views suggesting that ROS can have either a beneficial or detrimental impact on the host (2). In addition to its ability to control the relative concentrations of ROS, ecSOD can reduce neutrophil recruitment to the lung and dampen inflammatory responses during non-infectious insults (3–5). The product of ecSOD, H2O2, can directly induce neutrophil recruitment (6), but can also lead to cellular apoptosis (7). Interestingly, both H2O2 and O2·− have been shown to induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (8–10). Therefore, by directly influencing the oxidative environment in the ECM of various tissues, the level of ecSOD activity may impact pathogen survival as well as the function or recruitment of immune cells prior to, or during, infection.

The study of ecSOD is further warranted by the existence of polymorphisms in the human ecSOD gene that can lead to altered activity and localization of the enzyme. These polymorphisms have been associated with several inflammatory disorders including ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, type 2 diabetes, pre-eclampsia, and acute lung injury (11,12), although the molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Importantly, the ability of humans with these polymorphisms to respond to pathogenic infections has not been investigated.

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a Gram-positive intracellular bacterium that is widely used to study host-pathogen interactions. In the murine model of LM infection, the bacteria primarily infect the spleen and liver, where macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils facilitate early bacterial clearance (13). Our lab has recently shown that specific depletion of neutrophils with the anti-Ly6G (1A8) antibody reduces bacterial clearance and overall TNF-α production (14). Mice lacking TNF-α, or its receptor, are extremely susceptible to infection with LM and other pathogens (15–18). It has also been established that iNOS and components of the NADPH oxidase are required for efficient clearance of LM (19–21). However, how ecSOD activity impacts cytokine secretion, ROS/RNS levels, and the function of immune cells during bacterial infection has not been investigated.

To evaluate the importance of ecSOD in the acute response to bacterial infection, we took advantage of a novel experimental model. We utilized congenic mice that express high levels of ecSOD activity (ecSOD HI) (22), wild-type levels of ecSOD activity (ecSOD WT) (22), or lack ecSOD (ecSOD KO) (23,24). All of these mice share the C57Bl/6 (B6) background. The ecSOD HI mice express the ecSOD allele from the 129 strain of mice, and are characterized by higher levels of this enzyme in most tissues, including the liver. These mice are congenic to the ecSOD WT mice, which express the ecSOD allele from B6 mice (22).

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, we report here that ecSOD has a detrimental impact during LM infection by decreasing host survival, bacterial clearance, TNF-α and peroxynitrite (NO3·−) production, and neutrophil function. Importantly, the current research identifies an exciting and novel role by which an extracellular enzyme decreases the ability of mice to effectively eradicate an intracellular pathogen.

Materials and Methods

Mice and LM infections

Mice that lack ecSOD (ecSOD KO) (24), have high levels of ecSOD activity (ecSOD HI, expressing the 129 allele of ecSOD) (22), and have wild-type levels of ecSOD activity (ecSOD WT, expressing the ecSOD allele identical to the founder B6) (22) were bred in house. ecSOD KO mice were a kind gift from Dr. Cheryl L. Fattman (University of Pittsburgh). All of these mice were backcrossed to B6 mice. All studies used gender and age matched mice (2–4 months old), which were housed with food and water ad libitum in sterile microisolator cages with sterile bedding at the University of North Texas Health Science Center AAALAC accredited animal facility. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the US Department of Health and Human Services Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

LM 10403 serotype 1 was grown on brain–heart infusion (BHI) agar plates (BD Bacto, Sparks, MD), and virulent stocks were maintained by repeated passage through B6 mice. For infection of mice, log-phase cultures of LM grown in BHI broth were washed twice and diluted in PBS to the desired concentration. Mice were inoculated i.v. with ~ 104 LM for the experiments conducted at days 1 and 3 p.i. For experiments conducted at day 5 p.i., a dose of ~ 5 × 103 was used. Survival studies used a dose of ~ 1.5 × 104 for females and ~ 3 × 104 for males.

To determine LM CFUs, organs were homogenized in sterile water. Serial dilutions of the tissues were prepared, and 50 μL of each dilution was plated on BHI agar plates. After overnight incubation at 37°C, colonies were counted, and the LM CFUs recovered from each tissue were calculated.

Preparation of organs for flow cytometry and in vitro culture

Peripheral blood from the lateral tail vein was collected in a heparin solution with Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution + 2% FCS. RBCs were lysed with Tris Ammonium Chloride. Splenocytes were obtained by grinding whole spleens, and RBCs were lysed with Tris Ammonium Chloride. Liver leukocytes were obtained as previously described (25). Briefly, cell pellets obtained from homogenized livers were resuspended in 35% percoll media and layered upon 67.5% percoll, after which the gradient was centrifuged at 600g for 20 minutes, and low-density cells were collected from the gradient interface. Liver leukocytes were cultured in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, vitamins, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. All supplements were from Invitrogen-Gibco (Carlsbad, CA).

Flow cytometry

For cell surface staining, the following antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA): anti-Ly6G PE or FITC (1A8), anti-CD11b PE-Cy7 (M1/70), anti-CD16/CD32 (2.4G2); eBioscience (San Diego, CA): anti-IFN-γ APC (XMG1.2); BioLegend (San Diego, CA): NK1.1 PE (PK136); and Abcam (Cambridge, MA): anti-CD8 PE-TR (53-6.7). Cells were incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes with saturating amounts of the cell-surface antibodies, and anti-CD16/CD32 to block Fc receptors, in staining buffer (PBS + 2% FCS + 0.1% sodium azide). Cells were fixed in BD Stabilization Fixative (BD Biosciences). To accomplish intracellular cytokine staining, GolgiPlug containing brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) was added 4 hours before the harvest of the cell cultures. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized at 4°C for 20 minutes using an intracellular cytokine staining kit from BD Biosciences, and incubated in saturating amounts of anti-TNF-α or IFN-γ (BD Biosciences) at 4°C for 20 minutes. In order to measure apoptosis, Annexin V PE was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences). Data were acquired and analyzed using a Beckman Coulter FC500.

Measurement of RNS

To measure NO·, liver leukocytes from LM infected mice were cultured overnight with heat-killed LM (HKLM), and the supernatant was analyzed using the Nitric Oxide Quantitation Kit/Griess reagent (Active Motif, Inc). To determine the extent of NO3·− formation, protein nitrosylation levels were measured by Western blot. Livers from LM infected mice were homogenized as previously described (22), and the protein concentration was determined using the Lowry assay. 100 μg of liver protein was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and immunoblotted with a nitrotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody (clone 1A6; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). The extent of protein nitrosylation was normalized to β-actin protein levels. Detection and quantitation was performed using the FluorChem FC2 Imaging system (Alpha Innotech, Santa Clara, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (26). Briefly, 7-μm sections of frozen livers from LM infected or uninfected ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were prepared using a Leica CM 1850 cryostat. Anti-Ly6G (1A8) (BD Biosciences) and Difco Listeria O polyserum (BD Biosciences) were used to detect neutrophils and LM, respectively. Anti-Ly6G antibody was developed with anti-rat Alexafluor 594 (Molecular Probes) and Difco Listeria O polyserum was developed with anti-rabbit Alexafluor 488 (BD Biosciences). Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and a cover slip were added to the stained tissues. To view the stained tissue, an Olympus Ax70 fluorescent microscope was used and images were captured with an Olympus DP70 digital camera and analyzed with Image-Pro Plus software.

Quantification of TNF-α

ELISAs were performed on liver leukocyte culture supernatants using antibody pairs for TNF-α (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Cytokine levels were determined by comparison with standard curves generated from recombinant TNF-α (eBioscience). Data were analyzed using a Biotek EL808 spectrophotometer.

Neutrophil depletions

To specifically deplete neutrophils, the anti-Ly6G (1A8) antibody (27) was used as previously described (14). Briefly, 750 μg of anti-Ly6G or isotype control antibody (both from Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH) was injected intraperitoneally one day prior to i.v. injection of LM. Three days p.i., mice were sacrificed, CFUs determined, and flow cytometry utilized to confirm depletion of neutrophils.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted on the data. Bonferroni t-tests or Newman Keuls t-tests were used for post-hoc analyses. LM CFU data were log transformed prior to analysis, and are represented as such in the figures. Kaplan-Meier plots and logrank tests were used to compare the survival curves between groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant in all cases.

Results

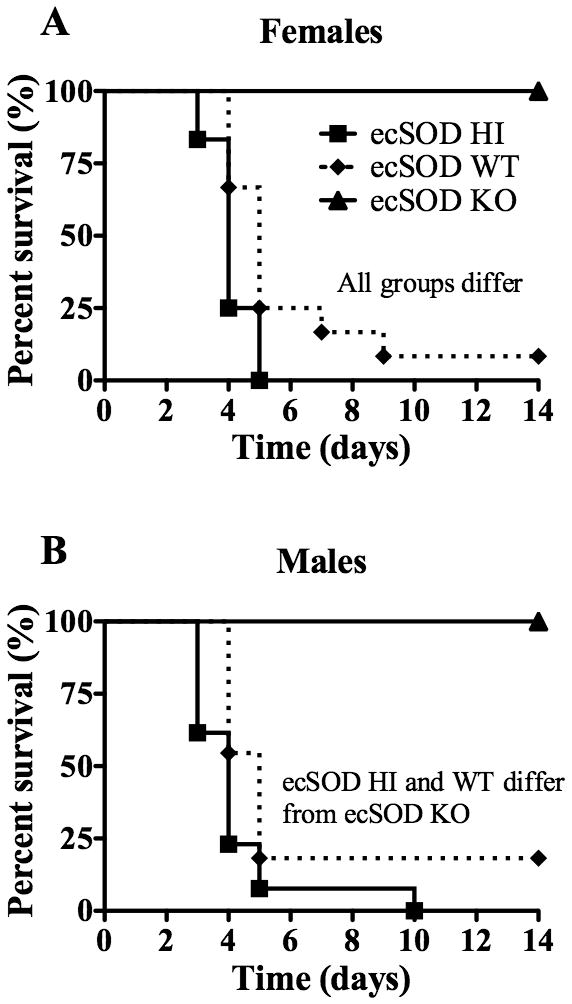

ecSOD activity increases susceptibility to LM infection

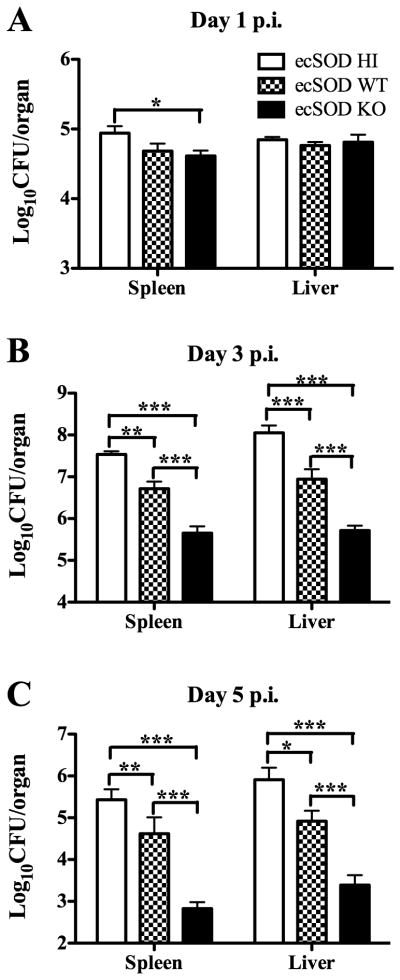

In order to determine how ecSOD activity impacts the susceptibility of mice to LM infection, ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM and survival was monitored (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, mice lacking ecSOD were 100% resistant to LM infection, regardless of gender. Mice that express the highest ecSOD activity were most susceptible to infection, while ecSOD WT mice demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to infection. Since most of the ecSOD WT and ecSOD HI mice succumbed to infection early, bacterial burdens in the spleens and livers of the three groups of mice were determined at days 1, 3, and 5 post-infection (p.i.) with sub-lethal doses of LM (Fig. 2). Interestingly, there were no differences in LM colony-forming units (CFUs) in the liver among the three groups of mice at day 1 p.i., though the ecSOD HI mice had slightly higher CFUs in the spleen when compared to the other mice (Fig. 2A). Bacterial burdens in the spleen and liver at days 3 (Fig. 2B) and 5 p.i. (Fig. 2C) were significantly decreased in mice lacking ecSOD relative to the other groups. Conversely, mice expressing the highest activity were least efficient in clearance of the bacteria at both time points. It was also confirmed that B6 mice have the same bacterial burden as ecSOD WT mice in the spleen and liver at day 3 p.i. (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that resistance to LM infection in mice is inversely related to the level of ecSOD activity.

Figure 1.

ecSOD activity enhances susceptibility of mice to LM infection. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM and survival was monitored in female (A) and male (B) mice. A log rank analysis detected a significant difference between survival curves as indicated in the graphs (p < 0.05). The data are combined from two independent experiments (n = 10 – 12/group).

Figure 2.

ecSOD activity decreases clearance of LM from the spleen and liver. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM. Spleen and liver CFUs were determined at day 1 p.i. (A), day 3 p.i. (B), and day 5 p.i. (C). Two-way ANOVAs detected significant differences between groups. An *, **, or *** indicate that the groups differ at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001 respectively. These data are representative of two independent experiments. All data are expressed as the mean +/− SEM (n = 4 – 5/group).

Lack of ecSOD does not enhance NK or CD8+ T cell responses in the liver

Previous publications have established that the production of IFN-γ, primarily from NK and CD8+ T cells, is critical for innate clearance of LM (25,28–30). Therefore, we investigated how ecSOD regulates the recruitment and activity of NK and CD8+ T cells during LM infection. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM. At day 1 p.i, splenocytes and liver leukocytes were analyzed to determine the percentage of NK and CD8+ T cells. ecSOD activity did not alter the percentage of NK1.1+ cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A), but did lead to a slight enhancement of the percentage of CD8+ T cells in the spleen and liver (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Interestingly, ecSOD activity enhanced the percentage of NK1.1+ cells secreting IFN-γ (Supplemental Fig. 1C), but did not significantly alter the percentage of CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ (Supplemental Fig. 1D), though the trend followed that of the NK1.1+ cells. Collectively, these data indicate that mice lacking ecSOD, which are able to efficiently clear early LM infection, do not show enhanced NK1.1+ or CD8+ T cell responses in the spleen or liver.

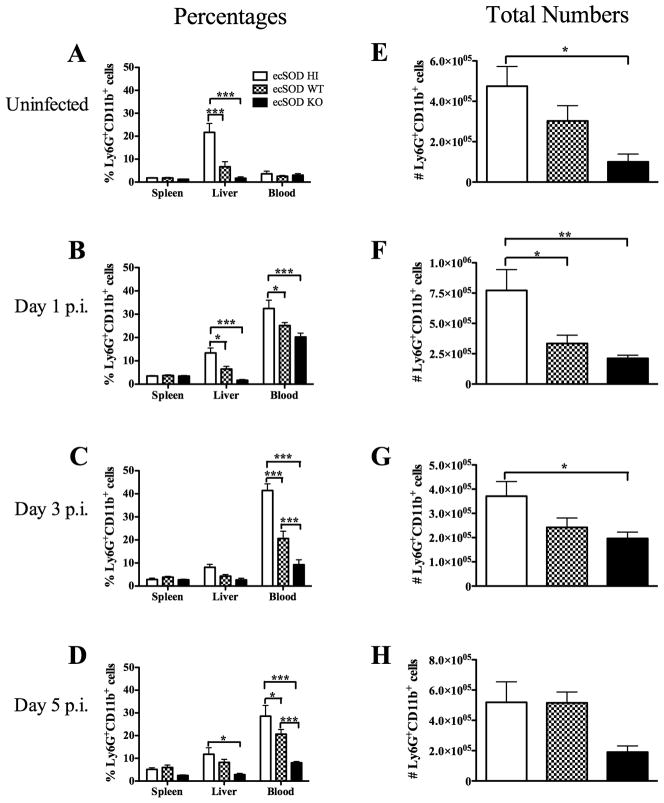

ecSOD activity enhances the percentage and total number of neutrophils in the liver

It has been observed that ecSOD activity can decrease neutrophil recruitment to the lung during inflammatory insults (4,5,31). However, it is not known if ecSOD activity impacts the recruitment of neutrophils to other organs. To investigate this possibility, the percentages and numbers of neutrophils in the spleen, liver, and blood of uninfected ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were quantified via flow cytometry (see Supplemental Fig. 2 for gating strategy). Surprisingly, there was an increased percentage of neutrophils in the livers of ecSOD HI mice when compared with the ecSOD KO mice, with ecSOD WT mice having intermediate percentages (Fig. 3A). Unlike the liver, the neutrophil populations did not differ in the blood or spleen of the three groups of mice prior to infection with LM. Neutrophil percentages were also examined at days 1, 3, and 5 p.i. to determine if ecSOD activity impacts infection-induced neutrophil recruitment. It was observed that the ecSOD HI mice continued to have higher percentages of neutrophils in the liver, as well as the blood, when compared with the ecSOD KO mice, with ecSOD WT mice having intermediate percentages (Fig. 3 B–D). The total number of neutrophils in the livers of the three groups of mice correlated with the percentages at each time point before, and after, infection (Fig. 3 EH). Given that neutrophils are required for resistance to LM infection in B6 mice (14), the fact that ecSOD activity results in decreased resistance yet increased neutrophil recruitment is counterintuitive, and deserves further investigation.

Figure 3.

ecSOD activity enhances the percentage and total number of neutrophils in the liver. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were left uninfected (A and E) or infected for 1 day (B and F), 3 days (C and G), or 5 days (D and H) with LM. Percentages of neutrophils in the spleen, liver, and blood (A–D) and total numbers (E–H) of neutrophils in the liver were determined by flow cytometry. Two-way (A–D) and one-way (E–H) ANOVAs detected significant differences between groups. An *, **, or *** indicate that the groups differ at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001 respectively. These data are representative of two independent experiments. All data are expressed as the mean +/− SEM (n = 4 – 5/group).

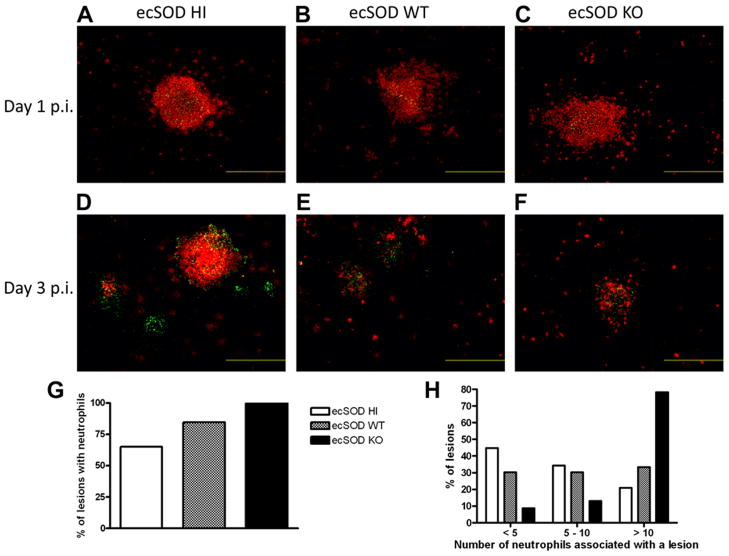

ecSOD activity regulates the localization of neutrophils to sites of LM lesions

In order to determine how ecSOD impacts the ability of neutrophils to localize with LM lesions, immunohistochemistry was performed. At day 1 p.i., there were no differences in the ability of neutrophils to localize with LM lesions in the livers of the three groups of mice (Fig. 4 A–C). At day 3 p.i., however, ecSOD activity clearly affected the ability of neutrophils to localize with LM lesions. Numerous LM lesions appeared to be completely devoid of neutrophils in the ecSOD HI mice, while fewer such neutrophil-free lesions were observed in the ecSOD WT mice. In the ecSOD KO mice, there were very few LM lesions, but neutrophils localized to these lesions 100% of the time (Fig. 4 D–F ). In the livers of ecSOD KO mice, neutrophils co-localized with LM lesions on every occasion, whereas fewer of the lesions in the ecSOD HI mice had associated neutrophils (Fig. 4G). Additionally, the ecSOD KO mice had the greatest number of neutrophils associated with individual LM lesions, when compared with the other groups of mice (Fig. 4H). These data suggest that ecSOD activity may be negatively impacting the ability of neutrophils to effectively combat the infection due to the lack of neutrophil/LM co-localization.

Figure 4.

ecSOD activity regulates the localization of neutrophils to sites of LM lesions. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM for 1 day (A–C) or 3 days (D–H) and livers were flash frozen. The livers were sectioned, stained for LM and Ly6G, and viewed on a fluorescent microscope. The green color indicates LM, red indicates neutrophils, and orange/yellow indicates neutrophils and LM in the same location. The fluorescent images are magnified by 100X, and the bars equal 500 μm. The data are representative of two mice per group. (G) The percentage of LM lesions that have associated neutrophils was determined. (H) The number of neutrophils associated with each LM lesion in the liver was determined. 103 lesions analyzed for the ecSOD HI, 39 lesions analyzed for the ecSOD WT, and 23 lesions analyzed for the ecSOD KO mice.

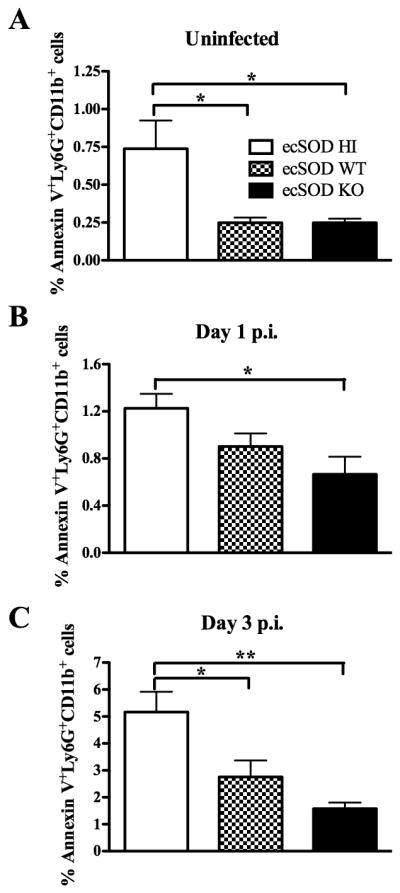

ecSOD activity increases neutrophil apoptosis in the liver

It has been shown that exogenous SOD can induce neutrophil apoptosis (32), and that apoptotic neutrophils are anti-inflammatory in nature (33,34). To determine if ecSOD regulates neutrophil apoptosis, liver leukocytes from the three groups of mice were stained for Ly6G, CD11b, and Annexin V. ecSOD activity did not preferentially increase the percentage of neutrophils undergoing apoptosis in uninfected mice or mice infected for one day (Supplemental Fig. 3A). However, at day 3 p.i. with LM, there was a higher percentage of neutrophils undergoing apoptosis in the ecSOD HI mice (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Importantly, due to the fact that the ecSOD HI mice have a higher percentage of neutrophils in the liver, there was a higher overall percentage of apoptotic neutrophils in the livers of uninfected ecSOD HI mice when compared with ecSOD WT and ecSOD KO mice (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, when mice were infected with LM for 1 (Fig. 5B) or 3 (Fig. 5C) days, the ecSOD HI mice had a higher percentage of apoptotic neutrophils than the ecSOD KO mice, with ecSOD WT mice having intermediate values. A similar trend was observed for the total numbers of neutrophils undergoing apoptosis in the liver (Supplemental Fig. 3B), once again due to the fact that the ecSOD HI mice contain increased percentages and numbers of neutrophils. These data suggest that ecSOD activity results in an increased number of apoptotic neutrophils, which may ultimately be detrimental to the immune response to LM infection.

Figure 5.

ecSOD activity increases neutrophil apoptosis in the liver. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were left uninfected (A) or infected with LM for 1 day (B), or 3 days (C). Percentages of apoptotic neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry in the liver. One-way ANOVAs detected significant differences between groups. An * or ** indicate that the groups differ at p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 respectively. These data are representative of two independent experiments. All data are expressed as the mean +/− SEM (n = 5/group).

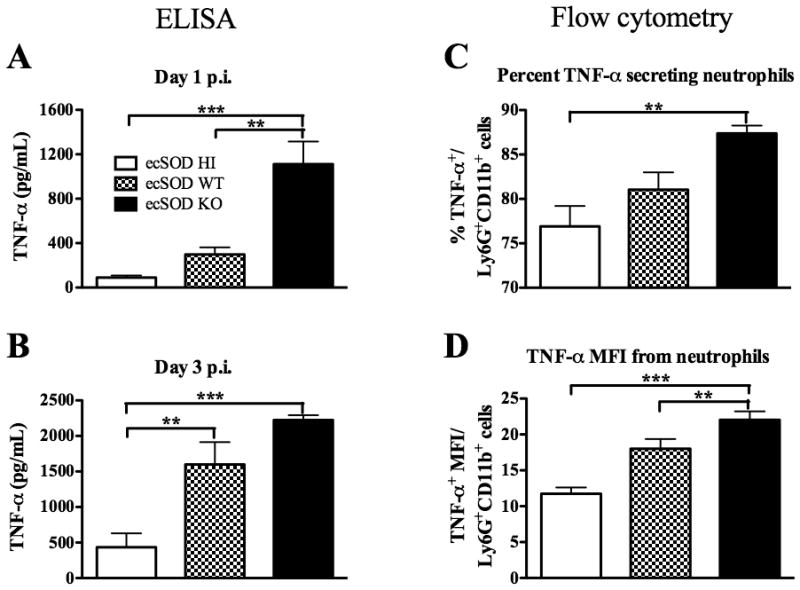

ecSOD activity decreases overall and neutrophil-specific TNF-α production

TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine necessary for protection against LM infection (15–18). Furthermore, ecSOD and apoptotic neutrophils have both been shown to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, including TNF-α (31,33). To determine if ecSOD was affecting the production of TNF-α in the liver, the three groups of mice were infected with LM. Liver leukocytes were isolated at 1 (Fig. 6A) or 3 (Fig. 6B) days p.i., and cultured with HKLM. Liver leukocytes from ecSOD KO mice produced higher concentrations of TNF-α when compared to those from ecSOD HI mice. Liver leukocytes from ecSOD WT mice produced intermediate concentrations of TNF-α (Fig. 6A and 6B). These data indicate that ecSOD activity decreases TNF-α production in the liver during LM infection.

Figure 6.

ecSOD activity decreases overall and neutrophil-specific TNF-α production. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM. The concentration of TNF-α was determined by ELISA following overnight HKLM stimulation of liver leukocytes from mice infected for 1 day (A) or 3 days (B). At 1 day p.i., neutrophils were gated upon based on their expression of Ly6G and CD11b. The percentage of this population in the liver that was TNF-α+ (C) was determined. The mean fluorescence intensity of TNF-α in the neutrophils (D) was determined. One-way ANOVAs detected significant differences between groups. An ** or *** indicate that the groups differ at p < 0.01 or p < 0.001 respectively. These data are representative of two independent experiments. All data are expressed as the mean +/− SEM (n = 5/group).

Liver leukocytes from the three groups of mice infected for 1 day with LM were also stained for intracellular TNF-α. The percentage of neutrophils secreting TNF-α was higher in the ecSOD KO mice when compared with ecSOD HI mice, with an intermediate percentage of neutrophils from ecSOD WT mice producing TNF-α (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, it was observed that neutrophils from ecSOD KO mice had a higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for TNF-α (Fig. 6D), indicating that increased amounts of TNF-α were being produced on a per-cell basis. These data demonstrate that ecSOD activity decreases overall and neutrophil-specific TNF-α production in the liver, which may partially explain how ecSOD activity influences susceptibility to LM infection.

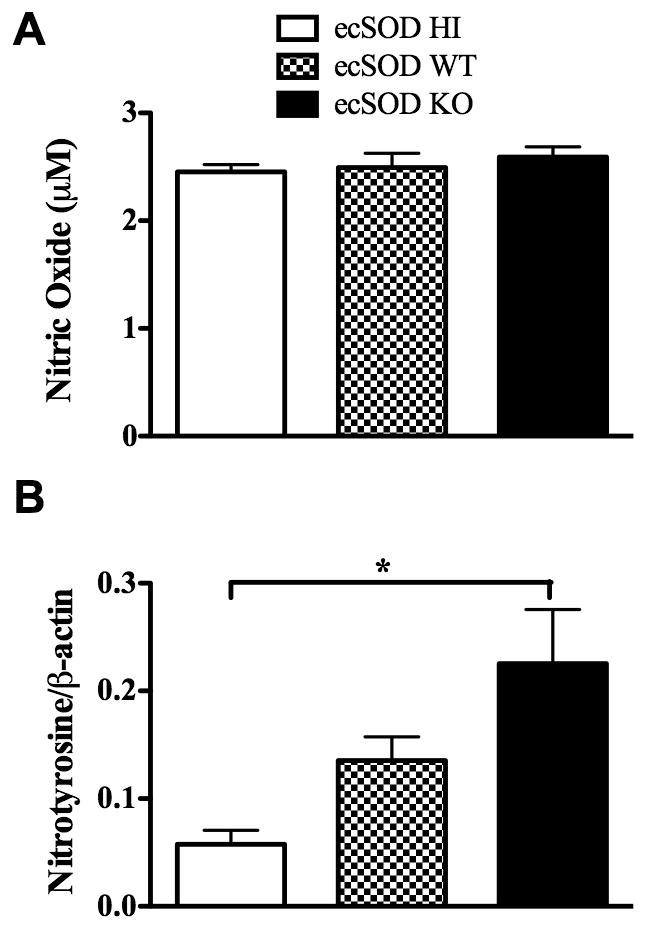

ecSOD activity reduces the extent of protein nitrosylation

It is known that ROS and RNS are important for clearance of LM (19–21). Although ecSOD directly regulates the extracellular concentrations of O2·− and H2O2, it is also known to indirectly regulate RNS levels (35). To investigate how ecSOD alters RNS levels, the three groups of mice were infected for one day with LM. Our data indicate that ecSOD did not alter the production of NO· from liver leukocytes (Fig. 7A). Next, the extent of protein nitrotyrosine formation, as a measure of NO3·− activity, was determined in liver homogenates after infection. Importantly, mice lacking ecSOD contained significantly increased levels of protein nitrotyrosine when compared to ecSOD HI mice, with ecSOD WT mice showing intermediate levels (Fig. 7B). Therefore, ecSOD activity reduces the amount of protein nitrosylation, suggesting lower production of NO3·−, which is known to be important for killing LM (36).

Figure 7.

ecSOD activity reduces NO3·− levels. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM, and at day 1 p.i. liver leukocytes were cultured overnight with HKLM. The supernatants were harvested and analyzed for NO· (A). ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were infected with LM, and at day 1 p.i. liver homogenates were analyzed for the presence of NO3·− (B). One-way ANOVAs detected significant differences between groups. An * indicates that the groups differ at p < 0.05. These data are representative of two independent experiments. All data are expressed as the mean +/− SEM (n = 3–5/group).

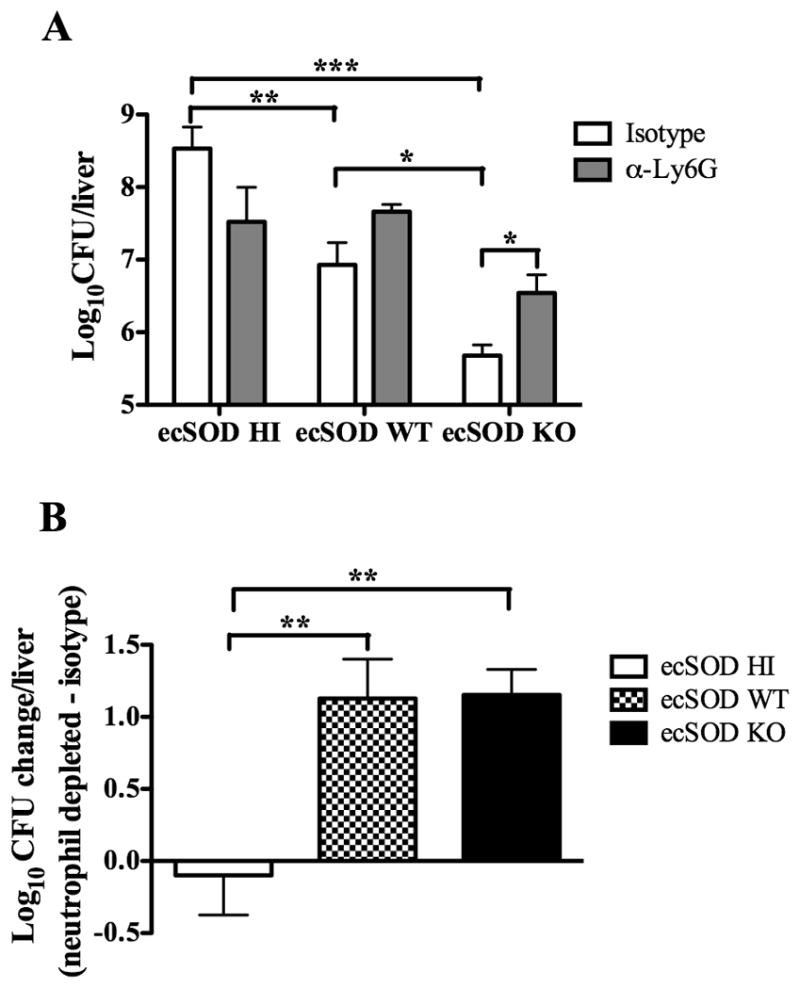

ecSOD-induced differences in liver CFUs are partially abrogated by neutrophil depletion

Because ecSOD activity decreases NO3·− levels and the ability of neutrophils to co-localize with LM, survive, and secrete TNF-α, it is reasonable to suggest that these decreases may influence the ability of neutrophils to clear infection. To test this possibility, ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were injected with the anti-Ly6G (1A8) neutrophil-depleting antibody or an isotype control, and were infected with LM the following day. Neutrophil depletion was confirmed by staining of blood leukocytes for neutrophil-specific cell surface molecules (Supplemental Fig. 4). In agreement with Fig. 2, isotype-treated ecSOD HI mice had the highest bacterial burden, ecSOD WT mice had intermediate bacterial burdens, and ecSOD KO mice had the lowest bacterial burden (Fig. 8A). With depletion of neutrophils, ecSOD HI mice actually showed a slight decrease in CFUs when compared to isotype-treated mice. Conversely, both the ecSOD WT and ecSOD KO mice had increased CFUs after depletion of neutrophils. This increase in CFUs was significant in the ecSOD KO mice (Fig. 8A). In order to better visualize these differences, the log change in CFUs was also determined. Fig. 8B shows a slight decrease in CFUs with depletion of neutrophils in the ecSOD HI mice. However, equivalent increases in CFUs in both the ecSOD WT and ecSOD KO mice were observed upon neutrophil depletion. These data suggest that neutrophils in the three groups of mice may be functioning differently. The neutrophils in the ecSOD HI mice may be ineffective, as depletion of these neutrophils led to a slight decrease in CFUs. Conversely, neutrophils in ecSOD WT mice function normally, as depletion increased CFUs, as previously observed (14). Finally, neutrophils in ecSOD KO mice function at a higher efficiency, as fewer neutrophils provide protection equivalent to that seen by a greater number of ecSOD WT neutrophils.

Figure 8.

ecSOD-induced differences in liver CFUs are partially abrogated by neutrophil depletion. ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice were depleted of neutrophils or injected with isotype control antibody one day prior to infection with LM. At 3 days p.i., CFUs were determined in the liver (A). The change in log CFUs was determined by subtracting the average log CFUs for neutrophil depleted mice from the isotype treated mice for ecSOD HI, ecSOD WT, and ecSOD KO mice (B). One-way ANOVAs detected significant differences between groups. An *, **, or *** indicate that the groups differ at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001 respectively. The data in (A) are representative of four independent experiments (n = 4–5/group). The data in (B) are combined from four independent experiments. All data are expressed as the mean +/− SEM.

Discussion

It has been previously established that the NADPH oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase (which produce O2·− and NO·, respectively) are important for eliminating bacteria, including LM (19–21). Additionally, it was recently shown that mitochondrial production of ROS is important for bacterial clearance (37). Our data now establish that ecSOD actually impairs the host’s ability to mount an effective innate immune response to bacterial infection. ecSOD HI mice were less resistant to LM infection, while ecSOD KO mice were more resistant than ecSOD WT mice. Surprisingly, ecSOD enhanced the mobilization of neutrophils to the livers, though this increase in neutrophils in the ecSOD HI mice appears to be detrimental to clearance of LM. In support of this notion, ecSOD activity was associated with decreased neutrophil co-localization with LM lesions in the liver. Furthermore, the extent of ecSOD activity correlated with increased neutrophil apoptosis in the liver, which may, in turn, suppress the generation of an effective immune response. Overall NO3·− levels, as well as TNF-α production by liver leukocytes, was also decreased with increasing ecSOD activity during LM infection. Similarly, ecSOD activity reduced both the percentage of liver neutrophils producing TNF-α and the amount of TNF-α being produced on a per-cell basis, suggesting that ecSOD may alter the functional activity of neutrophils.

Neutrophil depletion studies showed that neutrophils in the ecSOD HI mice did not contribute to bacterial clearance, as their removal resulted in a slight decrease in CFUs. On the other hand, depletion of neutrophils from ecSOD WT and ecSOD KO mice resulted in equivalent increases in liver CFUs, indicating their importance in bacterial clearance in these mice. Moreover, the functional activity of the ecSOD KO neutrophils, relative to that of neutrophils from ecSOD WT mice, appears to be increased, since similar protection is achieved by fewer neutrophils. Therefore, of the three groups, the neutrophils in the ecSOD KO mice are most efficient at controlling the LM infection. Our data suggest that ecSOD activity determines the contribution of neutrophils to clearance of LM from the liver.

These data further support our previous publication showing that neutrophils are required for protection against LM (14). Interestingly, a recent publication utilized the same neutrophil-depleting antibody and concluded that neutrophils are not required for clearance of LM (38). However, there are several experimental differences (source of B6 mice, dosage of LM, amount of depleting antibody utilized, timing of injection of depleting antibody, etc.) between the two studies that could have led to the discordant conclusions. One possibility is that the different B6 mice used in the studies expressed different amounts of ecSOD activity, which according to our present data can have a profound impact on the ability of neutrophils to provide protection against LM. Importantly, in both our studies utilizing the anti-Ly6G (1A8) antibody, we confirmed that neutrophils, but not monocytes, were effectively depleted ((14) and data not shown).

The altered activity of the neutrophils in mice with varying levels of ecSOD activity may be related to the degree of apoptosis. We provide data demonstrating that ecSOD activity increases the percentage of apoptotic neutrophils in the livers of uninfected and infected mice. Previous research suggests that increased apoptosis can suppress immune responses to LM (33). However, ecSOD may also be influencing the effector functions of neutrophils independent of the extent of apoptosis. Recent research has identified a population of cells that express Ly6G, but are characterized as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). These MDSCs suppress immune responses by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines and decreasing the bioavailability of L-arginine (39–41). Studies regarding MDSCs have shown a strong correlation with cancer and suppression of the immune response against tumors. However, it has also been shown that MDSC numbers are increased during bacterial and parasitic infections (41). It is possible that increased ecSOD activity leads to an alteration in the oxidative environment that is conducive to the induction of MDSCs, which could account for the differences in neutrophil function observed in the three groups of mice.

Although it has been previously shown that ecSOD can alter RNS levels, including NO· (35), our data indicate that ecSOD activity did not alter the production of NO· from liver leukocytes isolated from infected mice. It is possible that ecSOD regulates NO· availability in the vicinity of endothelial NOS (in the vasculature), but not NO· produced by iNOS-expressing leukocytes. It is well-established that ecSOD mediates the conversion of O2·− into H2O2 in the ECM of tissues (1). Therefore, mice lacking ecSOD likely generate increased amounts of O2·− in the ECM, which scavenge NO· to produce increased NO3·− levels. Indeed, our data show that ecSOD KO mice have increased levels of nitrosylated proteins, indicative of increased NO3·− levels, when compared to mice expressing ecSOD. It is known that NO3·− is a potent anti-microbial molecule that can directly kill LM (36). Therefore, it is possible that one mechanism contributing to enhanced clearance of LM in the ecSOD KO mice is increased NO3·− production.

The lack of a complete abrogation of differences in liver CFUs in the three groups of mice depleted of neutrophils indicates that there are other factors impacted by ecSOD activity. One way in which ecSOD may alter immune responses is through the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, which is supported by our TNF-α data. It is known that ecSOD has a high affinity for binding to collagen and heparin sulfate in the ECM, and plays an important role in protecting tissues from oxidative damage and inflammation. Oxidative stress and the resulting degradation of the ECM can lead to increased inflammation (42,43). The increased levels of extracellular O2·− in the ecSOD KO mice may lead to increased degradation of the ECM and release of hyaluronan (HA). Degraded HA fragments have been shown to bind to toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) and TLR-2, thus inducing inflammatory responses (44). Therefore, the increased fragmentation of HA in the ecSOD KO mice may lead to enhanced signaling through TLR-4 or TLR-2, accounting for the increased neutrophil activity, TNF-α secretion, and clearance of LM observed in our model.

It has been previously shown that 129 mice are more susceptible to LM infection than B6 mice (45,46). Our survival and CFU data obtained using ecSOD congenic mice may explain the observed differences in LM susceptibility between B6 and 129 mice. The 129 mice are genetically distinct from B6 mice in a variety of ways, with the difference in the ecSOD allele being just one example (22). Our current data establish that the ecSOD HI mice (expressing the 129 allele of ecSOD) are more susceptible to LM infection than ecSOD WT mice (expressing the B6 allele of ecSOD). This finding would support the idea that the increased susceptibility of 129 mice to LM infection is due to increased ecSOD activity.

Collectively, our data indicate that ecSOD activity is detrimental during acute bacterial infection. In a clinical setting, our findings could potentially lead to treatments aimed at eradicating pathogens. We would anticipate that suppressing ecSOD activity would increase pro-inflammatory responses, thus providing a useful therapeutic option to treat infections in conjunction with antibiotics or for antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suheung Lee and Amy Graham for their excellent technical assistance. Flow cytometry was performed in the Flow Cytometry and Laser Capture Microdissection Core Facility at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

This research was funded by a Texas Norman Hackerman Advanced Research Program Grant 000130-0025-2007 (to R.E.B.) and NIH RO1 HL70599 (to L.D.). A.N.S. was supported by NIH F32 AI072946.

Abbreviations

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ecSOD

extracellular superoxide dismutase

- LM

Listeria monocytogenes

- O2·−

superoxide

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- NO·

nitric oxide

- NO3·−

peroxynitrite

- BHI

brain–heart infusion

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- p.i

post-infection

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MDSCs

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- HA

hyaluronan

- B6

C57Bl/6

- HKLM

heat-killed LM

References

- 1.Marklund SL. Human copper-containing superoxide dismutase of high molecular weight. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hultqvist M, Olsson LM, Gelderman KA, Holmdahl R. The protective role of ROS in autoimmune disease. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao H, Arunachalam G, Hwang JW, Chung S, Sundar IK, Kinnula VL, Crapo JD, Rahman I. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects against pulmonary emphysema by attenuating oxidative fragmentation of ECM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15571–15576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007625107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jun S, Fattman CL, Kim BJ, Jones H, Dory L. Allele-specific effects of ecSOD on asbestos-induced fibroproliferative lung disease in mice. Free Rad Biol Med. 2011;50:1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowler RP, Nicks M, Tran K, Tanner G, Chang LY, Young SK, Worthen GS. Extracellular superoxide dismutase attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophilic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:432–439. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0057OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdan C, Rollinghoff M, Diefenbach A. Reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediates in innate and specific immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:64–76. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyoshi N, Oubrahim H, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. Age-dependent cell death and the role of ATP in hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis and necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1727–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510346103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorne E, Zmijewski JW, Zhao X, Liu G, Tsuruta Y, Park YJ, Dupont H, Abraham E. Role of extracellular superoxide in neutrophil activation: interactions between xanthine oxidase and TLR4 induce proinflammatory cytokine production. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C985–C993. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00454.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaramillo M, Olivier M. Hydrogen peroxide induces murine macrophage chemokine gene transcription via extracellular signal-regulated kinase- and cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent pathways: involvement of NF-kappa B, activator protein 1, and cAMP response element binding protein. J Immunol. 2002;169:7026–7038. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arcaroli JJ, Hokanson JE, Abraham E, Geraci M, Murphy JR, Bowler RP, Dinarello CA, Silveira L, Sankoff J, Heyland D, Wischmeyer P, Crapo JD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase haplotypes are associated with acute lung injury and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:105–112. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1566OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosta K, Molvarec A, Enzsoly A, Nagy B, Ronai Z, Fekete A, Sasvari-Szekely M, Rigo J, Jr, Ver A. Association of extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3) Ala40Thr gene polymorphism with pre-eclampsia complicated by severe fetal growth restriction. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;142:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pamer EG. Immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:812–823. doi: 10.1038/nri1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr KD, Sieve AN, Indramohan M, Break TJ, Lee S, Berg RE. Specific depletion reveals a novel role for neutrophil-mediated protection in the liver during Listeria monocytogenes infection. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2666–2676. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothe J, Lesslauer W, Lotscher H, Lang Y, Koebel P, Kontgen F, Althage A, Zinkernagel R, Steinmetz M, Bluethmann H. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF- mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1993;364:798–802. doi: 10.1038/364798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, Wakeham A, Kishihara K, Shahinian A, Wiegmann K, Ohashi PS, Kronke M, Mak TW. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell. 1993;73:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grivennikov SI, Tumanov AV, Liepinsh DJ, Kruglov AA, Marakusha BI, Shakhov AN, Murakami T, Drutskaya LN, Forster I, Clausen BE, Tessarollo L, Ryffel B, Kuprash DV, Nedospasov SA. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of TNF produced by t cells and macrophages/neutrophils: protective and deleterious effects. Immunity. 2005;22:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinauer MC, Deck MB, Unanue ER. Mice lacking reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity show increased susceptibility to early infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1997;158:5581–5583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacMicking JD, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher DS, Trumbauer M, Stevens K, Xie QW, Sokol K, Hutchinson N, Chen H, Mudgett JS. Altered Responses to Bacterial-Infection and Endotoxic-Shock in Mice Lacking Inducible Nitric-Oxide Synthase. Cell. 1995;81:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiloh MU, MacMicking JD, Nicholson S, Brause JE, Potter S, Marino M, Fang F, Dinauer M, Nathan C. Phenotype of mice and macrophages deficient in both phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Immunity. 1999;10:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jun S, Pierce A, Dory L. Extracellular superoxide dismutase polymorphism in mice: Allele-specific effects on phenotype. Free Rad Biol Med. 2009;48:590–596. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowler RP, Arcaroli J, Abraham E, Patel M, Chang LY, Crapo JD. Evidence for extracellular superoxide dismutase as a mediator of hemorrhage-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L680–L687. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00191.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlsson LM, Jonsson J, Edlund T, Marklund SL. Mice lacking extracellular superoxide dismutase are more sensitive to hyperoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg RE, Crossley E, Murray S, Forman J. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meeks KD, Sieve AN, Kolls JK, Ghilardi N, Berg RE. IL-23 is required for protection against systemic infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2009;183:8026–8034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harty JT, Bevan MJ. Specific immunity to Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of IFN gamma. Immunity. 1995;3:109–117. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg RE, Cordes CJ, Forman J. Contribution of CD8+ T cells to innate immunity: IFN-gamma secretion induced by IL-12 and IL-18. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2807–2816. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2807::AID-IMMU2807>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghio AJ, Suliman HB, Carter JD, Abushamaa AM, Folz RJ. Overexpression of extracellular superoxide dismutase decreases lung injury after exposure to oil fly ash. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L211–L218. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00409.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasui K, Kobayashi N, Yamazaki T, Agematsu K, Matsuzaki S, Ito S, Nakata S, Baba A, Koike K. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) as a potential inhibitory mediator of inflammation via neutrophil apoptosis. Free Radic Res. 2005;39:755–762. doi: 10.1080/10715760500104066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holub M, Cheng CW, Mott S, Wintermeyer P, van RN, Gregory SH. Neutrophils sequestered in the liver suppress the proinflammatory response of Kupffer cells to systemic bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:3309–3316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miles K, Clarke DJ, Lu W, Sibinska Z, Beaumont PE, Davidson DJ, Barr TA, Campopiano DJ, Gray M. Dying and necrotic neutrophils are anti-inflammatory secondary to the release of alpha-defensins. J Immunol. 2009;183:2122–2132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung O, Marklund SL, Geiger H, Pedrazzini T, Busse R, Brandes RP. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is a major determinant of nitric oxide bioavailability: in vivo and ex vivo evidence from ecSOD-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2003;93:622–629. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000092140.81594.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller M, Althaus R, Frohlich D, Frei K, Eugster HP. Reduced antilisterial activity of TNF-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages is due to impaired superoxide production. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3089–3097. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3089::AID-IMMU3089>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West AP, I, Brodsky E, Rahner C, Woo DK, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Walsh MC, Choi Y, Shadel GS, Ghosh S. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472:476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi C, Hohl TM, Leiner I, Equinda MJ, Fan X, Pamer EG. Ly6G+ neutrophils are dispensable for defense against systemic Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:5293–5298. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuda Y, Takahashi H, Kobayashi M, Hanafusa T, Herndon DN, Suzuki F. Three different neutrophil subsets exhibited in mice with different susceptibilities to infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity. 2004;21:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Condamine T, Gabrilovich DI. Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petersen SV, Oury TD, Ostergaard L, Valnickova Z, Wegrzyn J, Thogersen IB, Jacobsen C, Bowler RP, Fattman CL, Crapo JD, Enghild JJ. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) binds to type i collagen and protects against oxidative fragmentation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13705–13710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao F, Koenitzer JR, Tobolewski JM, Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW, Oury TD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase inhibits inflammation by preventing oxidative fragmentation of hyaluronan. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6058–6066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709273200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, Homer RJ, Goldstein DR, Bucala R, Lee PJ, Medzhitov R, Noble PW. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gahan CG, Collins JK. Non-dystrophic 129 REJ mice are susceptible to i.p. infection with Listeria monocytogenes despite an ability to recruit inflammatory neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:355–364. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheers C, I, McKenzie F. Resistance and susceptibility of mice to bacterial infection: genetics of listeriosis. Infect Immun. 1978;19:755–762. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.3.755-762.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.