Abstract

Many insects rely on the presence of symbiotic bacteria for proper immune system function. However, the molecular mechanisms that underlie this phenomenon are poorly understood. Adult tsetse flies (Glossina spp.) house 3 symbiotic bacteria that are vertically transmitted from mother to offspring during this insect's unique viviparous mode of reproduction. Larval tsetse that undergo intrauterine development in the absence of their obligate mutualist, Wigglesworthia, exhibit a compromised immune system during adulthood. In this study we characterize the immune phenotype of tsetse that develop in the absence of all of their endogenous symbiotic microbes. Aposymbiotic tsetse (GmmApo) present a severely compromised immune system that is characterized by the absence of phagocytic hemocytes and atypical expression of immunity-related genes. Correspondingly, these flies quickly succumb to infection with normally non-pathogenic E. coli. The susceptible phenotype exhibited by GmmApo adults can be reversed when they receive hemocytes transplanted from wild-type donor flies prior to infection. Furthermore, the process of immune system development can be restored in intrauterine GmmApo larvae when their moms are fed a diet supplemented with Wigglesworthia cell extracts. Our finding that molecular components of Wigglesworthia exhibit immunostimulatory activity within tsetse is representative of a novel evolutionary adaptation that steadfastly links an obligate symbiont with it's host.

INTRODUCTION

All metazoan life forms interact with prokaryotic organisms on a perpetual basis. These associations often result in a fitness advantage for one or both partners involved (1, 2). Insects represent a group of higher eukaryotes that harbor a well-defined bacterial microbiota. Unlike their mammalian counterparts, insects house less complex bacterial communities, are relatively inexpensive to maintain and produce large numbers of offspring in a short period of time. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of symbiotic bacteria as they relate to the proper function of their insect host's immune system. For example, Drosophila naturally infected with Wolbachia are protected (through an unknown mechanism) from several otherwise harmful RNA viruses (3). The malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae, is unusually susceptible to infection with Plasmodium parasites when they lack their commensal microbiota. In this case, symbiotic bacteria appear to mediate anti-Plasmodium immunity by activating basal expression of AMPs, inducing the production of phagocytic granulocytes, and directly generating anti-malarial reactive oxygen species (4, 5, 6).

Tsetse flies (Glossina spp.) harbor 3 symbiotic bacteria that regulate important aspects of their host's physiology. Two of these microbes, obligate Wigglesworthia and commensal Sodalis, are transferred to developing intrauterine progeny via maternal milk gland secretions (7). Tsetse's third symbiont, Wolbachia, is transferred via the germline (8). Tsetse that undergo intrauterine larval development in the absence of Wigglesworthia are immuno-compromised during adulthood. This phenotype is characterized by a significantly reduced population of phagocytic sessile and circulating hemocytes, and an unusual susceptibility to infection with pathogenic trypanosomes and normally non-pathogenic E. coli K12 (9, 10, 11). Further studies on the tsetse/Wigglesworthia symbiosis as it relates to host immunity have been obstructed by our inability to reconstitute symbiont-free flies with this bacterium.

In the present study we investigated the intimate relationship between immunity and symbiosis in tsetse by producing flies that underwent larval development in the absence of all endogenous microbes. We analyzed the immune system phenotype of aposymbiotic tsetse (GmmApo) following microbial challenge, and investigated whether loss of immunity in GmmApo flies could be rescued through either transfer of immune cells from healthy individuals or symbiont provisioning. We obtain results that reinforce the obligate nature of tsetse's relationship with Wigglesworthia, and provide further insights into the basic molecular mechanisms that underlie symbiont-induced maturation of host immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tsetse and bacteria

G. morsitans morsitans were maintained in Yale's insectary at 24°C with 50–55% relative humidity. These flies received defibrinated bovine blood (Hemostat Laboratories) every 48 hours through an artificial membrane feeding system (12). Designations of all tsetse cohorts used in this study, the composition of their symbiont populations, and the treatments they received are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Designation of tsetse cohorts used in this study, their symbiont status, and the treatment they received.

| Tsetse designation | Symbiont statusa | Origin/treatmentb | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gmm WT | Wgm, Sgm, Wol | none | none |

| Gmm Wgm- | Sgm, Wol | offspring of moms treated with Amp, yeast extract | 9 |

| Gmm Apo | apo | offspring of moms treated with Tet, yeast extract | 16 |

| Gmm Apo/WT | apo | received hemolymph transplant from GmmWT donors | this study |

| Gmm Apo/Apo | apo | received hemolymph transplant from GmmApo donors | this study |

| Gmm Apo/Sol | apo | received soluble fraction of GmmWT donor hemolymph | this study |

| Gmm Apo/Cell | apo | received cellular fraction of GmmWT donor hemolymph | this study |

| Gmm Apo/Wgm | apo | offspring of symbiont-cured moms complimented with Wgm cell extracts | this study |

| Gmm Apo/Sgm | apo | offspring of symbiont-cured moms complimented with Sgm cell extracts | this study |

| Gmm Apo/NB | apo | offspring of symbiont-cured moms that received no bacterial compliment | this study |

Wgm, Wigglesworthia; Sgm, Sodalis; Wol, Wolbachia; apo, aposymbiotic

Amp, ampicillin; Tet, tetracycline

Luciferase-expressing E. coli K12 (recE. colipIL) were produced via transformation with construct pIL, which encodes the firefly luciferase gene under transcriptional control of Sodalis' insulinase promoter (13). The assay used to quantify recE. colipIL cells in vivo was performed as described previously (13). GFP-expressing E. coli K12 (recE. coliGFP) were produced via electroporation with pGFP-UV plasmid DNA (Clontech). Sodalis were isolated from surface-sterilized G. m. morsitans pupae and cultured on Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells as described previously (14). Sodalis, which has a doubling time of approximately 24 h, were subsequently maintained cell-free in vitro at 25°C in Mitsuhashi-Maramorosch medium (1 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM MgCl2, 2.7 mM KCl, 120 mM NaCl, 1.4 mM NaHCO3, 1.3 mM NaH2PO4, 22 mM D (+) glucose, 6.5 g/L lactalbumin hydrolysate and 5.0 g/L yeast extract) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (14).

Tsetse infections

Systemic challenge of tsetse was achieved by anesthetizing flies with CO2 and subsequently injecting individuals with live bacterial cells using glass needles and a Narashige IM300 micro-injector. Per os bacterial challenges were performed by adding 500 colony forming units (CFU) of E. coli per 20 μl (the approximate amount consumed by a fly) of the total blood meal. The vertebrate host compliment system was heat-inactivated (56°C for 1 hr) prior to inoculating blood meals with bacterial cells. The number of bacterial cells injected or fed, control group designations, and sample size for all infection experiments are indicated in the corresponding figures and their legends.

Hemolymph collection and hemocyte quantification

Hemolymph collection from GmmWT and GmmApo flies was performed using the high injection/recovery method as described previously (15). Subsequent determination of circulating hemocyte abundance was performed using a Bright-Line hemocytomter (11). Sessile hemocyte abundance was quantified by subjecting GmmWT and GmmApo flies (n=3) to hemocoelic injection with blue fluorescent microspheres. 12 hr post-injection, flies were dissected to reveal tsetse's dorsal vessel (DV). Exposed tissue was rinsed 3 times with PBS to remove contaminating circulating hemocytes or any beads not engulfed by sessile hemocytes. The left-most panel is a Brightfield image of the 3 chambers that make up the DV (scale bar = 400 μm). The anterior-most chamber is indicated within a white circle, and the 2 remaining panels are the anterior chamber at higher magnification (scale bar = 80 μm). Engulfed beads were visualized microscopically by excitation with UV light (365/415 nm). Relative fluorescence, which was quantified using ImageJ software, represents the average amount of light emitted from 3 GmmWT and GmmApo individuals.

Quantitative analysis of immunity-related gene expression

For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis of immunity-related gene expression, whole flies were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extract using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Randomly-primed cDNAs were generated with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and qPCR analysis was performed using SYBR Green supermix and a Bio-Rad C1000 thermal cycler. Amplification primers are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Quantitative measurements were performed on 3 biological samples in duplicate and results were normalized relative to tsetse's constitutively expressed β-tubulin gene (determined from each corresponding sample). Fold-change data are represented as a fraction of average normalized gene expression levels in bacteria-infected flies relative to expression levels in corresponding uninfected controls. Values are represented as the mean (±SEM).

Hemolymph transplantation

Undiluted hemolymph was collected by removing one front fly leg at the joint nearest the thorax and then applying gentle pressure to the distal tip of the abdomen. Hemolymph exuding from the wound was collected using a glass micro-pipette and placed into a microfuge tube on ice. Four cohorts of newly emerged aposymbiotic recipient flies were used, 2 of which were designated GmmApo/WT or GmmApo/Apo based on whether they received hemolymph transplanted from WT or aposymbiotic donors, respectively. GmmApo/WT or GmmApo/Apo recipient flies received 1 μl of donor hemolymph (this volume represents approximately 1/3 of the total volume collected from donor flies). On day 8 post-transplantation, 3 of these flies were sacrificed to quantify hemocyte number using a Bright-Line hemocytometer. To separate GmmWT donor hemolymph into soluble and cellular fractions, samples were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min. The cellular component was resuspended in a volume of chilled anticoagulant buffer [70% MM medium, 30% anticoagulant citrate buffer (98 mM NaOH, 186 mM NaCl, 1.7 mM EDTA and 41 mM citric acid, buffer pH 4.5), vol/vol; 15] equal to the total amount of hemolymph from which they were collected. The remaining 2 cohorts of GmmApo recipient flies were injected with either 1 μl of cellular suspension (these flies are designated GmmApo/Cell), or 1 μl of the soluble hemolymph fraction (these flies are designated GmmApo/Sol).

All aposymbiotic recipient flies were challenged with either 103 CFU of live recE. colipIL or recE. coliGFP. Injections were performed using glass needles and a Narashige IM300 micro-injector. Quantification of recE. colipIL in recipient tsetse was performed as described above. Phagocytic capacity of transplanted hemocytes was determined by infecting GmmApo/Apo recipient flies with 103 CFU of live recE. coliGFP. Twelve hours post-challenge, hemolymph was collected from 3 individuals and hemocytes monitored for the presence of engulfed GFP-expressing bacterial cells. Hemolymph samples were fixed on glass microscope slides via a 2 min incubation in 2% paraformaldehyde. Prior to visualization using a Zeiss Axioscope microscope, slides were overlayed with VectaShield hard set mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

Bacterial complementation experiments

A cartoon illustrating in detail how bacterial compliment experiments were performed is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. Three cohorts (n= 120 individuals/group) of pregnant female tsetse were fed a diet containing tetracycline (40 μg/ml of blood) every other day for 10 days. Additionally, throughout the course of the entire experiment, all blood meals (3 per week) also contained vitamin-rich yeast extract (1% w/v) to restore fertility associated with the absence of Wigglesworthia (16). Ten days post-copulation, 2 cohorts of symbiont-cured females were regularly fed a diet supplemented with Wigglesworthia and Sodalis cell extracts. By timing treatments in this manner, larvae from the 1st gonotrophic cycle (GC) went through most of their development in the absence of bacterial compliment while those from the 2nd and 3rd GCs developed in the presence of bacterial compliment. Offspring of these females were designated GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm, respectively. Wigglesworthia was obtained by dissecting tsetse bacteriomes (an organ immediately adjacent to the midgut that houses this bacteria) from GmmWT females, while Sodalis was maintained in culture as describe above. GmmApo/Wgm females were fed 1 bacteriome equivalent per 4 females, and GmmApo/Sgm females were fed 4×107 Sodalis per ml of blood (these flies thus ingested ~1×106 Sodalis each time they fed). A 3rd control cohort of symbiont-cured females received no bacterial compliment (their offspring are designated GmmApo/NB), and a 4th cohort of wild-type offspring (GmmWT) served as another control. To confirm the aposymbiotic status of offspring from symbiont-cured moms (Supplemental Fig. 2), genomic DNA was extracted from larval offspring (3rd instar; n= 3) of all experimental cohorts using the Holmes-Bonner method (17). PCR (20μl reactions) was performed in an MJ Research thermalcycler using bacteria-specific primers (Supplemental Table 1) and the following cycle program: 95°C for 5 min. followed by 30 cycles at 95°C, 55°C and 72°C, each for 1 min, and a final 7 min elongation/extension at 72°C.

To determine whether complimenting symbiont-cured moms with bacterial cell extracts impacted the immune system phenotype of their offspring, qPCR was used (as described above) to monitor the expression of serpent and lozenge in larvae (1st, 2nd and 3rd instar) from each of 3 gonotrophic cycles (GC; n=3 individuals per group per GC). All remaining offspring were allowed to mature to adulthood. At this time 3 individuals from each cohort and GC were taken to determine circulating hemocyte abundance (as described above). Furthermore, qPCR was used to compare immunity-related gene expression in E. coli-challenged GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm individuals (n=3) from the 2nd GC of symbiont-cured moms. Finally, all remaining mature adult offspring were challenged with 103 CFU of live recE. coliGFP. Twelve hours post-challenge, hemolymph was collected and monitored to determine if hemocytes had engulfed GFP-expressing bacterial cells (n=3 individuals per group per GC). Hemolymph samples were fixed and visualized as described above.

Stats

Statistical significance between various treatments, and treatments and controls, is indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Survival curve comparisons were made by log-rank analysis using JMP (v9.0) software (www.jmp.com). Statistical analysis of qPCR data and hemocyte abundance was performed by Student's t test using Microsoft Excel software.

RESULTS

Aposymbiotic tsetse exhibit atypical hallmarks of cellular and humoral immunity

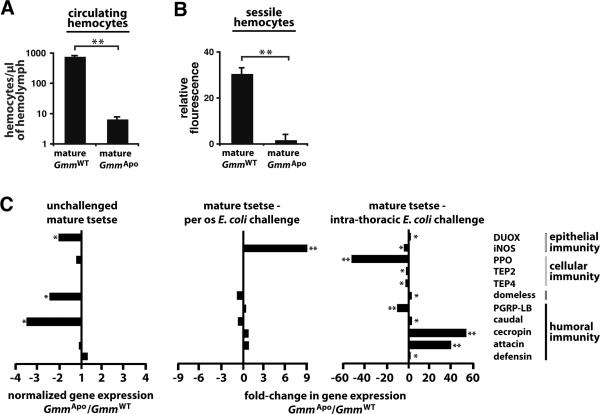

A positive correlation exists between the proper function of an insect's immune system and the dynamics of it's microbiome (18). In an effort to better define the relationship between symbiosis and immunity in tsetse, we fed pregnant female's on a diet supplemented with tetracycline and yeast. This antibiotic treatment clears all symbionts from the flies, while the vitamin-rich yeast extract rescues the loss of fertility associated with the absence of obligate Wigglesworthia (9, 16). We then investigated whether offspring that underwent intrauterine development in the absence of all symbiotic bacteria (GmmApo) exhibited an immune system phenotype during adulthood that was different from that of their WT counterparts that developed in the presence of their complete microbiome. To do so, we began by quantifying the number of circulating and sessile hemocytes present in 8 day old adult (hereafter referred to as `mature) GmmWT and GmmApo flies. Our results indicate that mature WT tsetse harbor 113× more circulating hemocytes per μl of hemolymph than do their aposymbiotic counterparts (GmmWT, 793 ± 34 hemocytes per μl of hemolymph; GmmApo, 7 ± 1 hemocytes per μl of hemolymph; Fig. 1A). To determine the functional relationship between symbiont status and sessile hemocyte abundance, we thoracically micro-injected WT and aposymbiotic adults with fluorescent microspheres. In both tsetse and Drosophila sessile hemocytes concentrate in large quantities around the anterior chamber of the fly's dorsal vessel (11, 19). Thus, we indirectly quantified sessile hemocyte number by measuring the fluorescent emission of injected microspheres that were found engulfed in this region. We observed that mature GmmWT flies engulfed 16× more microspheres than did age-matched GmmApo individuals (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Aposymbiotic tsetse display atypical hallmarks of cellular and humoral immunity.

(A) Number of circulating hemocytes per •l of hemolymph in mature GmmWT and GmmApo flies (n=3 individuals from each tsetse line). (B) Quantitative analysis of sessile hemocyte abundance adjacent to the anterior chamber of the dorsal vessel of mature GmmWT and GmmApo flies (n=3 individuals from each tsetse line). Relative fluorescence is proportional to the number of microspheres engulfed by sessile hemocytes and thus the number of these cells present in the region examined. (C) The effect of symbiont status and route of infection on the expression of selected immunity-related genes. Gene expression in uninfected GmmApo and GmmWT individuals is normalized relative to constitutively-expressed tsetse β-tubulin (left panel). Fold-change in the expression of immunity-related genes in GmmApo and GmmWT tsetse 3 d after per os (middle panel) and intra-thoracic (right panel) challenge with E. coli K12. All fold-change values are represented as a fraction of average normalized gene expression levels in bacteria-challenged flies relative to expression levels in PBS-injected controls. All quantitative measurements were performed on 3 biological samples in duplicate. Genes without a corresponding bar did not exhibit a fold-change in expression between samples compared, or their expression was undetectable via qPCR. Values are represented as means. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.005 (Student's t-test).

Previously we determined that several genes associated with humoral, cellular and epithelial immune pathways, including those that encode the antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) attacin and cecropin, as well as thioester-containing proteins (tep2 and tep 4), prophenoloxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), were expressed at significantly lower levels in GmmWgm− compared to GmmWT flies following infection with E. coli (11). In the present study we monitored expression of these same genes in age-matched GmmWT and GmmApo flies that were either unchallenged or 3 days post-challenge (dpc) with E. coli K12. Furthermore, we also evaluated the expression of peptidoglycan recognition protein LB (PGRP-LB), caudal, domeless and dual oxidase (DUOX). In tsetse and closely-related Drosophila, PGRP-LB and caudal serve as negative regulators of NF-kappaB-dependent antimicrobial peptide expression (10, 20, 21), while domeless is a cytokine receptor that regulates expression of tep4 through the `Janus Kinase Signal Transduction and Activator of Transcription' signaling pathway (22, 23). Finally, in Drosophila and mosquitoes, DUOX is involved in generating infection-induced antimicrobial reactive oxygen species (24, 25, 26).

Our expression analysis indicates that the presence of symbiotic bacteria during larval development induce basal immunity in tsetse. Specifically, we observed that DUOX, domeless and caudal are expressed at significantly lower levels in mature unchallenged GmmApo compared to GmmWT flies (Fig. 1C, left graph). Following per os challenge with E. coli, no significant difference in immunity-related gene expression (with the exception of iNOS) was observed between GmmWT and GmmApo flies (Fig. 1C, middle graph). However, systemic challenge resulted in a significant difference in the expression of all the genes we analyzed. Most notably, pathways associated with cellular immunity were significantly down-regulated in GmmApo compared to GmmWT individuals, while those associated with humoral immune responses were significantly up-regulated (Fig. 1C, right graph). These findings indicate that tsetse's symbiotic bacteria are closely associated with the development of their host's immune system during larval maturation, and it's subsequent proper function in unchallenged and E. coli challenged adults.

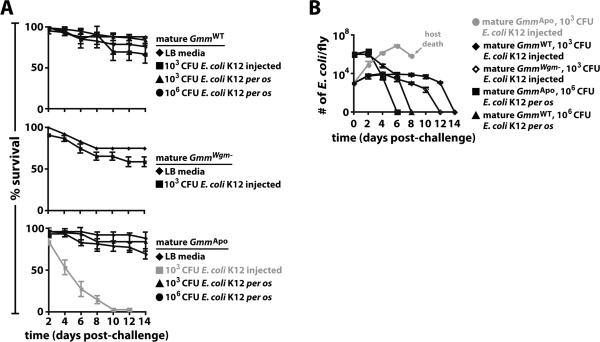

Aposymbiotic tsetse are highly susceptible to normally non-pathogenic E. coli

We next determined whether GmmApo individuals are more susceptible to challenge with E. coli than are WT tsetse or tsetse that lack only Wigglesworthia (GmmWgm−). To do so we compared percent survival of mature adults from these 3 tsetse lines following systemic challenge with E. coli K12. We determined that 67% of mature GmmWT individuals, and 59% of mature GmmWgm− individuals, survived systemic challenge with 103 CFU of E. coli (Fig. 2A, top and middle panels). In contrast, all age-matched GmmApo individuals perished by 12 dpc (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). We next challenged GmmWT and GmmApo flies per os with 103 and 106 CFU of E. coli, and found that all individuals survived this challenge (Fig. 1A, top and bottom panels). This finding suggests that mature GmmApo flies are considerably more susceptible to systemic challenge with a foreign microbe than are age-matched GmmWT and GmmWgm− individuals. Furthermore, tsetse's ability to overcome per os challenge with E. coli appears to be independent of symbiont status.

Figure 2. Symbiont status mediates tsetse's ability to survive challenge with E. coli K12.

(A) The effect of symbiont status on the survival of tsetse following systemic and per os challenge with E. coli K12. Mature adult GmmApo flies were significantly more susceptible to challenge with 103 CFU of E. coli than were age-matched GmmWT (bottom and top panels, p < 0.001) and GmmWgm− flies (bottom and middle panels, p < 0.001). Both GmmWT and GmmApo flies survived per os challenge with E. coli. Infection experiments were performed in triplicate, using 25 flies per replicate. (B) Average number (±SEM) of recE. colipIL per tsetse cohort over time (n=3 individuals per cohort per time point) following systemic and per os challenge with 103 CFU of bacteria. Values shown in grey represent lethal infections. By 8 dpc, not enough E. coli-injected GmmApo flies remained to quantify bacterial density.

To determine a cause for the variation in survival we observed between GmmWT, GmmWgm− and GmmApo individuals following challenge with E. coli, we monitored the dynamics of bacterial growth in each of these fly groups over time. When fed E. coli, both mature aposymbiotic and WT individuals cleared all E. coli. Following systemic challenge with 103 CFU of E. coli, bacterial densities within mature GmmWT flies reached 8.3×103 cells before being cleared. Interestingly, GmmWgm− flies, which perish following challenge with 106 CFU of E. coli (11), were able to clear all exogenous bacterial cells following challenge with this lower dose. On the other hand, bacterial density in GmmApo flies peaked at 7.8×106 on day 6 post-challenge, after which all flies soon perished (Fig. 2B). This observation suggests that aposymbiotic tsetse were unable to control systemic infection with E. coli and thus likely perished as a result of their inability to tolerate high densities of this bacterium in their hemolymph. These findings taken together indicate that GmmApo flies are significantly more susceptible to challenge with E. coli than are WT flies and flies that lack only Wigglesworthia.

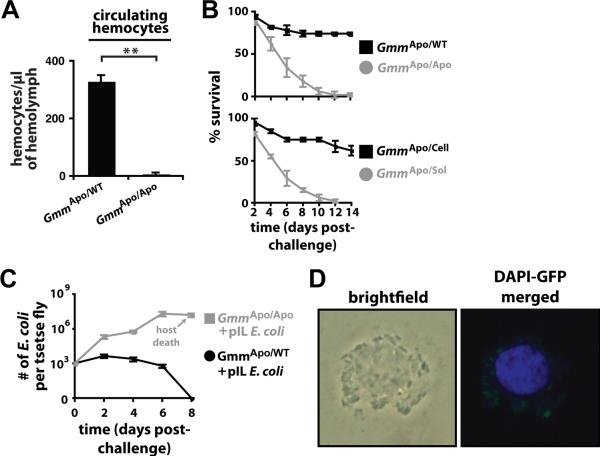

Hemocyte transfer from WT tsetse restores the ability of GmmApo adults to overcome infection with E. coli

We next set out to provide a definitive correlation between tsetse hemocytes and the fly's ability to overcome challenge with a foreign microbe. To do so we transplanted hemolymph from mature GmmWT and GmmApo individuals (donor flies) into the hemocoel of susceptible GmmApo flies (recipient flies are hereafter designated GmmApo/WT and GmmApo/Apo, respectively). Five days after this procedure we determined that GmmApo/WT flies harbored 330 (± 20.4) hemocytes per μl of hemolymph, while GmmApo/Apo flies harbored 5 (± 3.8) hemocytes per μl of hemolymph (Fig. 3A). We next investigated whether our hemolymph transplantation procedure was able to rescue the E. coli-susceptible phenotype exhibited by GmmApo flies. To do so we challenged GmmApo/WT and GmmApo/Apo individuals with 103 CFU of E. coli 3 days post-hemolymph transplantation, and subsequently monitored their survival over time. Our results indicate that 72% of GmmApo/WT flies survived for 14 days following challenge. In comparison, only 2% of GmmApo/Apo flies survived their challenge (Fig. 3B, top panel). These results demonstrate that GmmApo flies are able to clear a systemic challenge with E. coli after they receive a transplant of hemolymph from WT donors.

Figure 3. Hemocytes modulate tsetse's ability to overcome challenge with E. coli K12.

(A) Hemolymph was collected from GmmApo and GmmWT donor flies and immediately transplanted into GmmApo recipients. Five days post-hemolymph transplantation, hemocyte abundance in GmmApo/WT and GmmApo/Apo recipient flies was quantified microscopically using a hemocytometer. GmmApo/WT flies housed significantly more circulating hemocytes than did GmmApo/Apo flies (** = p < 0.005). (B) GmmApo/WT and GmmApo/Apo recipient flies were challenged with E. coli 3 days after receiving a hemolymph transplant. Significantly more GmmApo/WT individuals survived E. coli challenge than did their GmmApo/Apo counterparts (top panel; p < 0.001). Donor hemolymph was then divided into cellular and soluble fractions via centrifugation. Significantly more GmmApo/Cell individuals survived E. coli challenge than did their GmmApo/Sol counterparts (bottom panel; p < 0.001). (C) Average number (±SEM) of recE. colipIL per GmmApo/WT and GmmApo/Apo recipient fly over time (n=3 individuals per treatment per time point) following systemic challenge with 103 CFU of bacteria. Values shown in grey represent lethal infections. (D) 12 hr post-challenge with recE. coliGFP, hemolymph was collected, fixed on glass slides using 2% paraformaldehyde and microscopically examined for the presence of hemocyte-engulfed bacterial cells. GmmApo/WT recipient flies harbor engulfed bacterial cells.

We next investigated whether hemocytes, or a soluble antimicrobial or signaling molecule present in the transplanted hemolymph was responsible for restoring the resistant phenotype exhibited by recipient individuals. To address this issue we collected hemolymph from WT donors, separated it into soluble and cellular fractions by centrifugation, and then transplanted the separate fractions into 2 distinct groups of GmmApo flies. Finally, 3 days later we systemically challenged both groups of recipient flies with 103 CFU of E. coli K12. All aposymbiotic flies that received the soluble fraction of hemolymph from GmmWT donors (GmmApo/Sol) perished by day 12 post-challenge. In comparison, 62% of GmmApo recipients that received the cellular fraction of hemolymph from GmmWT donors (GmmApo/Cell) survived for 14 days following bacterial challenge (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). These host survival curves indicate that GmmApo flies survive challenge with E. coli when they had previously received a transplant of hemocytes, as opposed to soluble hemolymph molecules, from WT tsetse.

To determine a cause for the variation in survival we observed between these 2 groups, we monitored the dynamics of bacterial growth in each group over the course of the experiment. E. coli within GmmApo/Apo flies replicated exponentially until a peak density of 2.1×107 was reached at 6 dpc. This finding suggests that bacterial sepsis was the cause of high mortality we observed in this group of flies. In contrast, aposymbiotic recipients were able to clear all E. coli by 8 dpc when they had previously received a hemolymph transplant from GmmWT donors (Fig. 3C). More so, microscopic examination of hemolymph from GmmApo/WT flies showed that transplanted hemocytes engulfed the introduced E. coli (Fig. 3D). Our results demonstrate that immune resistance can be restored in adult aposymbiotic tsetse if they harbor hemocytes transplanted from their WT counterparts.

Supplementation of Wigglesworthia to symbiont-cured females restores immune system development in aposymbiotic offspring

Previous experiments revealed that the milk gland population of tsetse's obligate symbiont, Wigglesworthia, must be present during the development of immature stages in order for subsequent adults to exhibit a functional cellular immune system (11). To date we have been unable to culture Wigglesworthia and thus can not recolonize aposymbiotic flies with this bacterium. To circumvent this impediment we tested whether we could restore the process of immune system development in GmmApo offspring by supplementing the diet of pregnant, symbiont-cured females with Wigglesworthia-containing extracts of bacteriome tissue collected from WT females. A detailed description of the experimental design we used to test this theory is provided in the Materials and Methods and Supplemental Fig. 1.

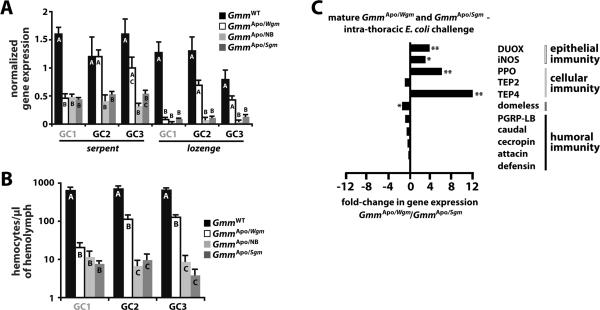

In brief, two treatment cohorts of pregnant GmmWT females were fed a diet supplemented with tetracycline and yeast extract (16). Ten days post-copulation, these symbiont-cured females began receiving either Wigglesworthia or Sodalis cell extracts in every blood meal. The immune system phenotype of offspring from these females (GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm, respectively) was compared to that of control cohort offspring from symbiont-cured moms that received no bacterial supplement (GmmApo/NB) and offspring from GmmWT moms. We first evaluated the relative abundance of transcripts that encode the transcription factors `Serpent' and `Lozenge'. In Drosophila, these molecules direct hemocyte differentiation, or hematopoiesis, during embryogenesis and early larvagenesis (27). In tsetse, larvae that develop in the absence of Wigglesworthia express significantly less serpent and lozenge than do their WT counterparts (11). In the present study we found that GmmApo/Wgm, GmmApo/Sgm and GmmApo/NB larva from the 1st gonotrophic cycle (GC) expressed significantly less serpent and lozenge than did GmmWT larva. However, after the onset of bacterial supplementation, GmmApo/Wgm and GmmWT larva from the 2nd and 3rd GCs expressed comparable levels of serpent and lozenge, while GmmApo/NB and GmmApo/Sgm larva expressed less (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Dietary supplementation of Wigglesworthia cell extracts to symbiont-cured female tsetse induces immune system development in their aposymbiotic offspring.

Three groups of pregnant female tsetse were provided 4 blood meals supplemented with the antibiotic tetracycline to clear all of their endogenous microbiota. Two cohorts of these symbiont-cured females then received diets supplemented with either Wigglesworthia or Sodalis cell extracts to compliment the absence of these bacteria. The third group of symbiont-cured females received no bacterial compliment. Finally, a fourth group of WT females received no tetracycline or bacterial complementation. Offspring of these females, which are designated GmmApo/Wgm, GmmApo/Sgm, GmmApo/NB and GmmWT, respectively, were collected from 3 gonotrophic cycles (GC) and subsequently monitored to determine their immune system phenotype. GC1 is indicated in grey to signify that bacterial compliment of GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm moms began after their first larval offspring were fully developed. (A) qPCR was performed on larval offspring (n=3 larva per cohort per GC) to determine their levels of serpent and lozenge expression. (B) Circulating hemocyte abundance in adult offspring (n=3 flies per cohort per GC) was quantified microscopically using a Bright-Line hemocytometer. In (A) and (B), bars with different letters indicate a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between samples. (C) Fold-change in the expression of immunity-related genes in GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm adults challenged with E. coli. Adult flies used for this experiment were from the 2nd GC of symbiont-cured moms. All fold-change values are represented as a fraction of average normalized gene expression levels in bacteria-challenged flies relative to expression levels in PBS-injected controls. Genes without a corresponding bar did not exhibit a fold-change in expression between samples compared, or their expression was undetectable via qPCR. All quantitative measurements were performed on 3 biological samples in duplicate. Values are represented as means. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.005.

Because serpent and lozenge expression can be indicative of hematopoiesis, we next compared the number of hemocytes present in GmmApo/Wgm adults to that found in age-matched GmmWT, GmmApo/NB and GmmApo/Sgm flies. We found that the provisioning of Wigglesworthia extracts to symbiont-cured females resulted in an increase in the number of circulating hemocytes present in their offspring. Specifically, hemocyte density in GmmApo/Wgm adults from GCs 2 and 3 was significantly greater (113 ± 33 and 127 ± 21 hemocytes/μl of hemolymph, respectively) than that found in age-matched GmmApo/NB (7 ± 3 and 9 ± 4 hemocytes/μl of hemolymph, respectively) and GmmApo/Sgm flies (10 ± 4 and 4 ± 1 hemocytes/μl hemolymph, respectively), but significantly less than that of GmmWT adults (733 ± 104 and 681 ± 68 hemocytes/μl hemolymph, respectively; Fig. 4B). Correspondingly, we observed that prophenoloxidase and tep4, which are expressed predominantly by hemocytes (28, 29), are found at significantly higher levels in adult GmmApo/Wgm compared to GmmApo/Sgm adults (from GC2) following systemic challenge with E. coli (Fig. 4C). A similar pattern was observed with genes involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species (DUOX and iNOS). Interestingly, humoral immunity-associated genes (AMPs and their regulators) were expressed at similar levels in E. coli-challenged GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm adults.

Our results suggest that feeding symbiont-cured moms a diet supplemented with Wigglesworthia cell extracts induces a physiological response that partially restores immune system development in their aposymbiotic offspring. Specifically, GmmApo/Wgm larvae exhibit increased expression of the hematopoietic transcription factors serpent and lozenge, and as adults these flies present a functional immune system characterized by the presence of circulating phagocytic hemocytes. Furthermore, the expression of genes involved in epithelial and cellular immunity is enhanced in GmmApo/Wgm adults.

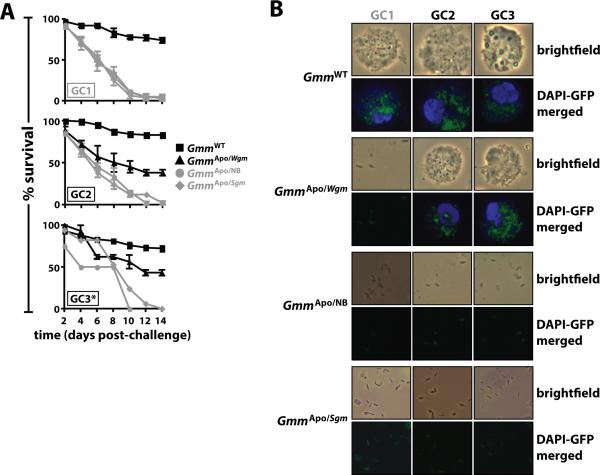

GmmApo/Wgm flies are resistant to E. coli challenge

We observed that GmmApo/Wgm offspring exhibit hallmarks of enhanced immunity. Thus, we next tested whether mature GmmApo/Wgm adults would be resistant to systemic challenge with E. coli K12, while age-matched GmmApo/Sgm and GmmApo/NB flies, would not. To this end, we observed that 38% and 43% of GmmApo/Wgm adults from GCs 2 and 3, respectively, survived challenge with 103 E. coli (Fig. 5A). Correspondingly, microscopic inspection of hemolymph from E. coli-resistant GmmApo/Wgm adults revealed the presence of phagocytic hemocytes that harbored internalized E. coli cells (Fig. 5B). In contrast, GmmApo/NB and GmmApo/Sgm flies were highly susceptible to E. coli challenge, and like their GmmApo counterparts, all perished within the 14 day experimental period (Fig. 5A). This susceptible phenotype likely resulted from the fact that GmmApo/NB and GmmApo/Sgm adults are devoid of phagocytic hemocytes (Figs. 4B and 5B). These findings suggest that aposymbiotic tsetse can survive infection with an otherwise lethal dose of E. coli if they complete intrauterine development while their moms were fed a diet containing Wigglesworthia cell extracts. This immuno-competent phenotype exhibited by GmmApo/Wgm adults likely results from the presence of phagocytic hemocytes in their hemolymph.

Figure 5. GmmApo/Wgm flies exhibit resistance to challenge with E. coli.

(A) Percent survival of mature GmmApo/Wgm, GmmApo/Sgm, GmmApo/NB and GmmWT adults from 3 GCs following challenge with 103 CFU of E. coli K12. Significantly more GmmApo/Wgm flies from the 2nd GC survived this challenge than did age-matched GmmApo/Sgm and GmmApo/NB individuals (p < 0.01). However, significantly fewer GmmApo/Wgm flies from these GCs survived this challenge than did their WT counterparts (p < 0.01). Values shown in grey represent lethal infections. Sample sizes are as follows: GC1 (n=25 flies per replicate for all tsetse cohorts) and GC2 (n=25 flies per replicate for GmmWT and GmmApo/Wgm flies; n=20 for GmmApo/Sgm and GmmApo/NB flies) infection experiments were performed in triplicate for all tsetse groups. GC3 is denoted with an asterisk because not enough GmmApo/Sgm and GmmApo/NB offspring were produced to perform the experiment in triplicate (even in the presence of yeast extract, the fecundity of symbiont-cured females drops over time). Thus, statistical comparisons between these two groups were not performed. (B) Twelve hours post- challenge with recE. coliGFP, hemolymph was collected from all individuals (n=3 flies per group per GC) to monitor for the presence of phagocytic hemocytes. Samples were processed as previously described. In (A) and (B), GC1 is indicated in grey to signify that bacterial compliment of GmmApo/Wgm and GmmApo/Sgm moms began after their first intrauterine larval offspring were approximately mid-way through their 3rd developmental instar.

DISCUSSION

Symbiotic bacteria are gaining increased recognition as potent modulators of insect immunity (18, 30). In the present study we provide evidence that tsetse's symbiotic bacteria are intimately associated with the maturation of their host's immune system during juvenile development and it's subsequent proper function during adulthood. We determined that aposymbiotic (GmmApo) flies derived from symbiont-cured moms present a severely compromised cellular immune system, and as such are highly susceptible to systemic infection with normally non-pathogenic E. coli. This immuno-compromised phenotype can be reversed when GmmApo adults receive hemocytes transplanted from WT individuals. Furthermore, the process of immune system development in GmmApo larvae can be restored when their symbiont-cured moms are fed a diet supplemented with Wigglesworthia cell extracts. Our results demonstrate that evolutionary time has stably anchored the obligate association between tsetse and Wigglesworthia such that this bacterium directly engenders immunity, and thus ultimately the fecundity, of it's host. In return, tsetse provides Wigglesworthia with a protective and metabolite-rich niche that has enabled this bacterium to survive in this environment for at least 50 million years (31).

Tsetse that undergo intrauterine larval development in the absence of only Wigglesworthia (GmmWgm−) exhibit a compromised immune system that, when compared to WT flies (GmmWT), is characterized by a 70% reduction in the number of phagocytic hemocytes (11). In the present study we found that eliminating all symbiotic bacteria from female tsetse markedly enhances the immuno-compromised phenotype of their offspring. In fact, GmmApo adults harbor virtually no circulating (99% less than GmmWT adults) or sessile hemocytes and are correspondingly more susceptible to systemic infection with E. coli than are WT tsetse and tsetse that lack only Wigglesworthia. GmmWgm− flies, which undergo intrauterine maturation in the presence of Sodalis and Wolbachia, house approximately 40× more circulating hemocytes than do their aposymbiotic counterparts and are more tolerant to E. coli challenge. (11). The enhanced immunity exhibited by GmmWgm− individuals in comparison to their aposymbiotic counterparts suggests that the presence of Sodalis and Wolbachia during intrauterine development may induce a limited degree of immune system maturation in their tsetse host. Although no experimental evidence exists that demonstrates a functional role of this nature for Sodalis, Wolbachia exhibits immuno-modulatory properties in other insect models. For example, Drosophila treated with antibiotics to clear their Wolbachia infections are significantly more susceptible to a range of RNA viruses (32, 33). Furthermore, the mosquito Aedes aegypti can be stably transinfected with an exogenous strain of Wolbachia (wMelPop; 34). The presence of wMelPop appears to activate the immune system of offspring from transinfected females, which subsequently exhibit enhanced immunity against a range of pathogens (35, 36). Interestingly, unlike our laboratory colony, many natural populations of tsetse do not harbor Sodalis and/or Wolbachia, but are apparently still immuno-competent (37). It remains to be seen whether these symbionts play a role in stimulating immune system development in natural populations of tsetse.

Many insects, including Drosophila, Anopheles and Manduca, likely rely on their cellular immune systems as a potent first line of defense against systemic infection with pathogenic bacteria (38, 39, 40, 41). Similarly, tsetse become susceptible to infection with E. coli after their hemocyte function is abrogated via the uptake of polystyrene microspheres (11). In this study we provide further evidence that tsetse's ability to overcome systemic infection with E. coli also depends on the presence of a functional cellular immune system. First, E. coli kills GmmApo adults despite the fact that they express dramatically more of the AMPs cecropin and attacin than do resistant WT flies. This finding suggests that AMPs alone are insufficient for tsetse to overcome systemic infection with E. coli. Secondly, GmmApo adults survive this same infection if they had previously received hemolymph transplanted from WT donors. However, when WT donor hemolymph was separated into cellular and soluble fractions prior to transplantation, only GmmApo recipients that received the cellular fraction (hemocytes) exhibited an E. coli-resistant phenotype. Thus, hemolymph-soluble factors such as an AMPs, hematopoeitic molecules or reactive oxygen species, presumably do not induce E. coli resistance when transplanted into GmmApo flies. Instead resistance appears fixed to the cellular immunity-related activity of hemocyte-mediated phagocytosis.

Beneficial microbes in the human gut produce symbiosis factors that, unlike disease-causing virulence factors produced by pathogenic microbes, promote favorable health-related outcomes (42). For example, the human commensal, Bacteroides fragalis, produces one such molecule called polysaccharide A (PSA). Colonization of germ-free mice with this bacterium restores CD4+ T cell populations to levels conventionally found in mice that house their native microbiota. This process is consistent with B. fragalis PSA-induced development of secondary lymphoid tissues. B. fragalis PSA mutants fail to induce these systemic responses in germ-free animals (43). Similarly, mouse intestinal microbiota serve as a source of peptidoglycan (PGN) that enhances the efficacy of phagocytic neutrophils against pathogenic bacteria (44). To date no immuno-modulatory symbiosis factors have been characterized from insect-associated microbes. In this study we demonstrated that immune system development in GmmApo larvae was activated when their moms were fed a diet supplemented with extracts of Wigglesworthia cells. This finding suggests that a molecular component of this obligate bacterium can actuate a trans-generational priming response in the intrauterine larvae of symbiont-cured females. This response restores the process of immune system maturation in larvae in the absence of milk gland-associated Wigglesworthia. Tsetse houses 2 distinct populations of Wigglesworthia, the first of which is found extracellularly in female milk gland secretions. These bacterial cells presumably colonize developing intrauterine larvae, which receive maternal milk for nourishment during tsetse's unique mode of viviparous reproduction (7). Tsetse's second population of Wigglesworthia resides within the cytosol of specialized bacteriocytes that collectively compromise an organ located immediately adjacent to midgut called the bacteriome (45). Interestingly, GmmWgm− adults, which arise from female tsetse that house bacteriome-associated Wigglesworthia but lack their milk gland population, are immuno-compromised (11). Thus, this population of Wigglesworthia is insufficient to stimulate immune system development in intrauterine GmmWgm− larvae. However, Wigglesworthia-containing bacteriome extracts supplemented in the diet of symbiont-cured moms can stimulate immune system development in GmmApo larvae. Bacteriome-associated Wigglesworthia appear to produce the molecule(s) required to actuate immune system development in GmmApo offspring, but they are concealed within the cytosol of bacteriocytes.

The mechanism by which Wigglesworthia extracts induce immune system development in GmmApo larvae is currently unknown. In the mammalian system, symbiosis factors are translocated from the gut lumen to peripheral target immune tissues. In the mouse model B. fragalis cells, or B. fragalis PSA, is presumably taken up by gut-associated dendritic cells, which subsequently migrate to outlying lymphoid tissues where they signal for the differentiation of T cell lineages (43). In a similar manner, PGN shed by mouse intestinal microbiota is translocated from the luminal side of the gut epithelia into the circulatory system. A positive correlation exists between the concentration of PGN present in host sera and neutrophil function (44). Further experiments are required in the tsetse system to determine if immuno-stimulatory Wigglesworthia molecules are transported to the developing larvae where they exhibit direct activity, or if they act locally in the gut to induce a maternally-derived systemic response that subsequently induces larval immune system development.

Nutritional symbioses between bacteria and insects are well-documented (46, 47). The relationship between tsetse and Wigglesworthia presumably also has a nutritional component, as flies that lack this bacterium are reproductively sterile (48, 9). In fact, Wigglesworthia's highly reduced genome encodes many vitamins and cofactors that are missing from tsetse's vertebrate blood-specific diet (49). In this study we demonstrate that the tsetse-Wigglesworthia symbiosis is multi-dimensional in that this microbe is also intimately involved in activating the development of it's host's immune system. As such tsetse may be exploitable as relatively simple and efficient model for deciphering the basic molecular mechanisms that underlie symbiont-induced maturation of host immunity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Yineng Wu for assistance with qPCR, and members of the Aksoy lab for critical review of the manuscript.

Funding This work was generously funded by grants to S.A. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; AI051584), National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS; 069449) and the Ambrose Monell Foundation (http://www.monellvetlesen.org/).

Abbreviations

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- DV

dorsal vessel

- qPCR

real-time quantitative PCR

- WT

wild-type

- GC

gonotrophic cycle

- PGRP-LB

peptidoglycan recognition protein LB

- tep

thioester-containing protein

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- DUOX

dual oxidase

- dpc

days post-challenge

REFERENCES

- 1.Wernegreen JJ. Genome evolution in bacterial endosymbionts of insects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:850–861. doi: 10.1038/nrg931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran NA. Symbiosis. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R866–R871. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong Y, Manfredini F, Dimopolous G. Implications of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000423. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science. 2010;329:1353–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1190689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Clayton AM, Sandiford SL, Souza-Neto SL, Mulenga M, Dimopoulos G. Natural microbe-mediated refractoriness to Plasmodium infection in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2011;322:855–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1201618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attardo GM, Lohs C, Heddi A, Alam UH, Yildirim S, Aksoy S. Analysis of milk gland structure and function in Glossina morsitans: milk protein production, symbiont populations and fecundity. J. Insect Physiol. 2008;54:1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Q, Ruel TD, Zhou W, Moloo SK, Majiwa P, O'Neill SL, Aksoy S. Tissue distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia infections in tsetse flies, Glossina spp. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2000;14:44–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pais R, Lohs C, Wu Y, Wang J, Aksoy S. The obligate mutualist Wigglesworthia glossinidia influences reproduction, digestion, and immunity processes of its host, the tsetse fly. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:5965–5974. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00741-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Wu Y, Yang G, Aksoy S. Interactions between mutualist Wigglesworthia and tsetse peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP-LB) influence trypanosome transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12133–12138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901226106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss BL, Wang J, Aksoy S. Tsetse immune system maturation requires the presence of obligate symbionts in larvae. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moloo SK. An artificial feeding technique for Glossina. Parasitol. 1971;68:507–512. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss BL, Wu Y, Schwank JJ, Tolwinski NS, Aksoy S. An insect symbiosis is influenced by bacterium-specific polymorphisms in outer membrane protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15088–15093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dale C, Maudlin I. Sodalis gen. nov. and Sodalis glossinidius sp. nov., a microaerophilic secondary endosymbiont of the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans morsitans. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999;49:267–27. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-1-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castillo JC, Robertson AE, Strand MR. Characterization of hemocytes from the mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;36:891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alam U, Medlock J, Brelsford C, Pais R, Lohs C, Balmand S, Carnogursky J, Heddi A, Takac P, Galvani A, Aksoy S. Wolbachia symbiont infections induce strong cytoplasmic incompatibility in the tsetse fly, Glossina morsitans morsitans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002415. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes DS, Bonner JB. Preparation, molecular weight, base composition and secondary structure of giant ribonucleic acid. Biochem. 1973;12:2330–2338. doi: 10.1021/bi00736a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss BL, Aksoy S. Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elrod-Erickson M, Mishra S, Schneider DS. Interactions between the cellular and humoral immune responses in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:781–784. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaidman-Rémy A, Hervé M, Poidevin M, Pili-Floury S, Kim MS, Blanot D, Oh BH, Ueda R, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Lemaitre B. The Drosophila amidase PGRP-LB modulates the immune response to bacterial infection. Immunity. 2006;24:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryu J, Kim S, Lee H, Bai J, Nam Y, Bae JW, Lee DG, Shin SC, Ha EM, Lee WJ. Innate immune homeostasis by the homeobox gene caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science. 2008;319:777–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1149357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krzemien J, Dubois L, Makki R, Meister M, Vincent A, Crozatier M. Control of blood cell homeostasis in Drosophila larvae by the posterior signaling centre. Nature. 2007;446:325–328. doi: 10.1038/nature05650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makki R, Meister M, Pennetier D, Ubeda JM, Braun A, Daburon V, Krzemien J, Bourbon HM, Zhou R, Vincent A, Crozatier M. A short receptor downregulates JAK/STAT signalling to control the Drosophila cellular immune response. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha E, Oh C, Bae YS, Lee W. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science. 2005;310:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1117311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S, Molina-Cruz A, Gupta L, Rodrigues J, Barillas-Mury C. A peroxidase/dual oxidase system modulates midgut epithelial immunity in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2010;327:1644–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.1184008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira JH, Gonçalves RL, Lara FA, Dias FA, Gandara AC, Menna-Barreto RF, Edwards MC, Laurindo FR, Silva-Neto MA, Sorgine MH, Oliviera PL. Blood meal-derived heme decreases ROS levels in the midgut of Aedes aegypti and allows proliferation of intestinal microbiota. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001320. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung SH, Evans CJ, Uemura C, Banerjee U. The Drosophila lymph gland as a developmental model of hematopoiesis. Development. 2005;132:2521–2533. doi: 10.1242/dev.01837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strand MR. The insect cellular immune response. Insect Sci. 2008;15:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bou-Aoun R, Hetru C, Troxler L, Doucet D, Ferrandon D, Matt N. Analysis of thioester-containing proteins during the immune response of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Innate Immunol. 2011;3:52–64. doi: 10.1159/000321554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cirimotich CM, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. Native microbiota shape insect vector competence for human pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:307–310. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X, Li S, Aksoy S. Concordant evolution of a symbiont with its host insect species: molecular phylogeny of genus Glossina and its bacteriome-associated endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:49–58. doi: 10.1007/pl00006444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science. 2008:322–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1162418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osborne SE, Leong YS, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. Variation in antiviral protection mediated by different Wolbachia strains in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000656. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, Fong AW, Sidhu M, Wang YF, O'Neill SL. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2009;323:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1165326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kambris K, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science. 2009;326:134–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1177531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moriera LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffrey JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O'Neill SL. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindh JM, Lehane MJ. The tsetse fly Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (Diptera: Glossina) harbours a surprising diversity of bacteria other than symbionts. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matova N, Anderson KV. Rel/NF-kappaB double mutants reveal that cellular immunity is central to Drosophila host defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16424–16429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605721103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haine ER, Moret Y, Siva-Jothy MT, Rolff J. Antimicrobial defense and persistent infection in insects. Science. 2008;322:1257–1259. doi: 10.1126/science.1165265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blandin SA, Levashina EA. Phagocytosis in mosquito immune responses. Immunol. Rev. 2007;219:8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eleftherianos I, Xu M, Yadi H, Ffrench-Constant RH, Reynolds SE. Plasmatocyte-spreading peptide (PSP) plays a central role in insect cellular immune defenses against bacterial infection. J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212:1840–1848. doi: 10.1242/jeb.026278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazmanian SK, Kasper DL. The love-hate relationship between bacterial polysaccharide and the host immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:849–858. doi: 10.1038/nri1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;15:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke TB, Davis KM, Lysenko ES, Zhou AY, Yu Y, Weiser JN. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat. Med. 2010;16:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aksoy S. Tsetse – a haven for microorganisms. Parasitol. Today. 2000;16:114–118. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosokawa T, Koga R, Kikuchi Y, Meng X, Fukatsu T. Wolbachia as a bacteriocyte-associated nutritional mutualist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:769–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911476107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Douglas AE. Lessons from studying insect symbioses. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nogge G. Sterility in tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans Westwood) caused by loss of symbionts. Experientia. 1976;32:995–996. doi: 10.1007/BF01933932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akman L, Yamashita A, Watanabe H, Oshima K, Shiba T, Hattori M, Aksoy S. Genome sequence of the endocellular obligate symbiont of tsetse flies, Wigglseworthia glossinidia. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:402–407. doi: 10.1038/ng986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.