Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) to improve wound healing after total hip arthroplasty (THA) and its influence on the development of postoperative seromas in the wound area.

Materials

The study is a prospective randomised evaluation of NPWT in patients with large surgical wounds after THA, randomising patients to either a standard dressing (group A) or a NPWT (group B) over the wound area. The wound area was examined with ultrasound to measure the postoperative seromas in both groups on the fifth and tenth postoperative days.

Results

There were 19 patients randomised in this study. Ten days after surgery, group A (ten patients, 70.5 ± 11.01 years of age) developed seromas with an average size of 5.08 ml and group B (nine patients, 66.22 ± 17.83 years of age) 1.97 ml. The difference was significant (p = 0.021).

Conclusion

NPWT has been used on many different types of traumatic and non traumatic wounds. This prospective, randomised study has demonstrated decreased development of postoperative seromas in the wound and improved wound healing.

Introduction

Negative pressure wound treatment (NPWT) has become a widely used therapy for many different indications in the treatment of traumatic, non traumatic and even chronic wounds [1–4]. Recently, the indication to use the NPWT on closed surgical wounds, especially after severe trauma, has been suggested [5–7]. The principle application of this technique is easy. A constant negative pressure is applied to the closed wound. A suction tube is connected to a sponge which is placed over the sutured wound to which a self-sticking membrane is attached. The membrane must be put on the skin close to the wound to seal the wound and create a sterile surrounding area [1, 8]. The suggested mechanisms of action are the stimulation of bloodflow, increased oxygen saturation and angiogenesis [5, 9].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the potential effect on the reduction of postoperative seromata and to evaluate any potential influence on wound healing and laboratory inflammatory values.

Material and methods

Nineteen consecutive patients who were scheduled for a total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis of the hip were randomised in either group A, receiving the standard wound dressing of our department, consisting of a dry wound coverage, or group B, receiving a NPWT over the sutured wound area. The surgical intervention was identical for both groups. The surgical approach was posterolateral, and the prostheses were all from the same manufacturer (Brehm, Germany). All patients received two Redon drains, one in the deep area of the wound close to the prostheses and one above the closed fascia. The postoperative physiotherapy and mobilisation was also identical for both groups. Both groups received perioperative prophylaxis with antibiotics either Augmentin (amoxicillin trihydrate with potassium clavulanate) or ciprofloxacin. The NPWT group (group B) was treated with a PREVENA™ system (KCI, San Antonio, USA). The PREVENA system was left on the wound for five days including the day of surgery. All patients underwent an ultrasound (Zonare, Z.one Ultra SP 4.2, Erlangen, ZONARE Medical Systems, Inc., Mountain View, USA) of the wound with volume measurement which is performed using a tool provided by the manufacturer. Additional ultrasounds were performed preoperatively as a control for potential soft tissue abnormalities and then postoperatively on the fifth and tenth days after surgery. Furthermore, blood samples were taken preoperatively and on days five and ten postoperatively. Blood values assessed the red blood count (Hb), the white blood count (leukocytes), C-reactive protein (CRP), thrombocytes, the INR and the Quick. Postoperatively, the amounts of wound secretion in the Redon drain canisters were recorded, the length of the incision was measured, and the duration of prophylaxis with antibiotic was also noted as well as any potential secretion of the wound.

For statistics, the Mann-Whitney U-test for two independent groups was applied (exact statistics). Baseline p-values were two-tailed and otherwise one-tailed in favour of the NPWT-group.

Informed consent was obtained from each patient. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Ten patients in group A with a mean age of 70.0 ± 11.01 years and nine patients in group B with a mean age of 66.22 ± 17.83 years were randomised (p = 0.673). The wound size for group A was 13.25 ± 3.02 cm and for group B 12.44 ± 1.81 cm (p = 0.920). The Redon drains showed a mean total volume of secretion for group A of 669 ± 478 ml and for group B 511 ± 239 ml (p = 0.421). The Redon drain boxes were changed an average of 4.1 ± 1.37 times for group A and 3.22 ± 1.09 times for group B (p = 0.096). The ultrasound on day five showed a volume of 2.02 ± 2.74 ml for group A and 0.58 ± 1.21 ml (p = 0.102) for group B; on day ten there was a mean volume of 5.08 ± 5.11 for group A and 1.97 ± 3.21 ml for group B (p = 0.021). A seroma was present in 90% of the patients in group A and in 44% of group B. Group A received antibiotics for a mean of 11.8 ± 2.82 days and group B for 8.44 ± 2.24 days (p = 0.005). The laboratory values can be found in Table 1. In group B a secretion from the wound after five days was seen in only one patient. This patient removed the Redon drain by himself on the first postoperative day. In group A five patients with a secretion of the wound after five days were noted.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings in both groups

| Group | Hb first day post surgery (g/dl) | Hb fifth day post surgery (g/dl) | Hb tenth day post surgery (g/dl) | Leuko-cytes first day post surgery (×103/ul) |

Leuko-cytes fifth day post surgery (×103/ul) |

Leuko-cytes tenth day post surgery (×103/ul) |

Platelets first day post surgery (×103/ul) |

Platelets fifth day post surgery (×103/ul) |

Platelets tenth day post surgery (×103/ul) |

INR pre surgery | Quick pre surgery (%) | CRP first day post surgery (mg/l) | CRP fifth day post surgery (mg/l) | CRP tenth day post surgery (mg/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean group A | 10.22 | 9.86 | 10.94 | 9.10 | 7.56 | 8.30 | 188,000 | 251,900 | 365,300 | 1.005 | 95.10 | 85.61 | 83.09 | 44.06 |

| SD group A | 1.50 | 1.19 | 0.72 | 2.39 | 1.92 | 2.60 | 44,312 | 57,842 | 116,573 | 0.070 | 9.09 | 37.34 | 56.51 | 30.66 |

| Mean group B | 11.30 | 11.07 | 10.87 | 9.46 | 7.88 | 8.22 | 228,333 | 336,777 | 420,111 | 0.946 | 99.56 | 74.91 | 78.88 | 22.39 |

| SD group B | 1.34 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 2.18 | 2.35 | 2.52 | 102,404 | 128,345 | 115,706 | 0.041 | 1.33 | 29.96 | 29.31 | 8.51 |

| p value | 0.108 | 0.031 | 0.267 | 0.661 | 0.348 | 0.484 | 0.389 | 0.075 | 0.158 | 0.033 | 0.239 | 0.563 | 0.452 | 0.069 |

Discussion

Since its first application NPWT has been used widely in the treatment of chronic and acute wounds [1–3, 10–15]. Many indications for the use of NPWT have been added since its first use [2, 16]. Several studies have shown a beneficial effect on wound healing and a reduction of complications combined with a safe administration and low risk of side effects for the patient [17, 18].

To our knowledge this is the first study to show a significant reduction of seromas in the wound area of closed wounds. This study detects the subcutaneous seroma by ultrasound, which is unique in this field of research, relating to NPWT of closed wounds. The high sensitivity of a standardised evaluation of the wound area by imaging modalities showed the reduction of a seroma directly underneath the surgical incision. The reason why a reduction of wound seroma occurs is still not completely understood. Horch et al. showed a significantly increased bloodflow, a significantly higher oxygen saturation and post capillary venous filling compared to a baseline measurement before a NPWT device was added to healthy skin [9]. This might be one reason why better wound healing was achieved with NPTW in our study. In addition to the reduction of seroma we have seen better apposition of the wound edges (Figs. 1 and 2). Another finding which might lead to a better wound healing was the reduction of drainage fluid in the Redon drain boxes in the NPWT group. A complication that might be of interest is the communication between the Redon drains and the PREVENA™ system. This might cause a suction of air into the vacuum of the sponge or cause a leakage of the NPWT system. In this study not a single leakage occurred in the PREVENA™ group. After the removal of the NPWT device a secretion through the wound occurred in only one patient. In contrast to the control group where 50% of the patients still showed secretion of wound after five days. The secretion of wound debris through the incision always carries the risk of development of bacterial infection and delayed healing. This phenomenon was also observed by other study groups who were evaluating NPWT devices over closed wounds. Stannard et al. showed a reduction of haematoma and drainage of injuries after high energy trauma [5, 19]. Decarbo et al. recommended the NPWT for use on high risk wounds, for example, after total ankle replacement [6], but none of them could prove the reduction of a seroma in the wound area.

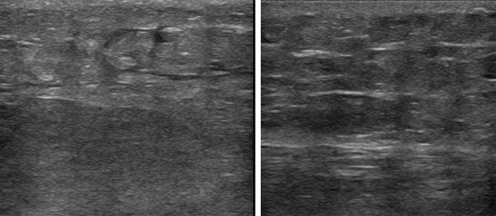

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound of the wound area of two patients with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and no seroma and a scar tissue after ten days

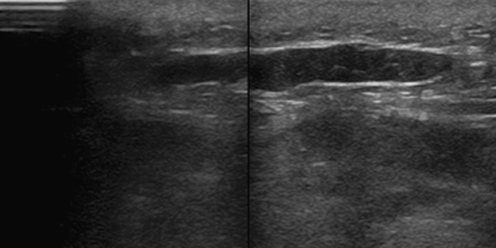

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound of the wound area with a postoperative seroma in the control group

Another interesting finding is the reduction of CRP between the fifth and tenth days postoperatively in the Prevena group. The mean values decreased from 78.87 to 22.38 mg/l in comparison with 83.09 to 44.06 mg/l in the control group. This might be related to the reduced secretion of the wound and the better wound healing, but the reason for this finding is still unknown and needs further evaluation. Our findings correlate with findings in other studies. In a different context Kaplan et al. showed a faster recovery of the patients who suffered severe trauma with soft tissue defects if a NPWT device was applied early, i.e. on day one or two of treatment in comparison to patients who received this treatment later [20]. The early application of NPWT seems to have a positive impact on wound healing. In this study the NPWT was applied immediately after surgical closure of the wound.

One limitation of the study is the relatively small number of patients included, such that a single case could skew the results. But we have seen that in 50% of the control cases a secretion after five days after surgery was still present in contrast to only one patient in the PREVENA™ group. Furthermore, 90% of the patients in the control group showed a seroma on day ten after surgery and the mean volume of the seroma was statistically significantly lower in the PREVENA™ group compared to the control group. Another limitation is the fact that we only used the product of a single vendor. For all other vendors and products the portability has still to be evaluated.

Conclusion

Application of NPWT on closed wounds after orthopaedic surgery might help to reduce the complications of a prolonged wound healing and postoperative seroma in the wound area.

Acknowledgments

Matthias H. Brem gave scientific presentations for KCI. The PREVENATM wound treatment system was provided by KCI free of charge.

Footnotes

Milena Pachowsky and Johannes Gusinde both contributed equally to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kanakaris NK, Thanasas C, Keramaris N, Kontakis G, Granick MS, Giannoudis PV. The efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy in the management of lower extremity trauma: review of clinical evidence. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl 5):S9–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Runkel N, Krug E, Berg L, Lee C, Hudson D, Birke-Sorensen H, Depoorter M, Dunn R, Jeffery S, Duteille F, Bruhin A, Caravaggi C, Chariker M, Dowsett C, Ferreira F, Martinez JM, Grudzien G, Ichioka S, Ingemansson R, Malmsjo M, Rome P, Vig S, Martin R, Smith J (2011) Evidence-based recommendations for the use of negative pressure wound therapy in traumatic wounds and reconstructive surgery: steps towards an international consensus. Injury 42 Suppl 1:S1–12. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(11)00041-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lehner B, Fleischmann W, Becker R, Jukema GN (2011) First experiences with negative pressure wound therapy and instillation in the treatment of infected orthopaedic implants: a clinical observational study. Int Orthop. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1274-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Stannard JP, Singanamala N, Volgas DA (2010) Fix and flap in the era of vacuum suction devices: what do we know in terms of evidence based medicine? Injury 41(8):780–786. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, McGwin G, Jr, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma. 2006;60(6):1301–1306. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195996.73186.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeCarbo WT, Hyer CF (2010) Negative-pressure wound therapy applied to high-risk surgical incisions. J Foot Ankle Surg 49 (3):299–300. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.DeFranzo AJ, Argenta LC, Marks MW, Molnar JA, David LR, Webb LX, Ward WG, Teasdall RG. The use of vacuum-assisted closure therapy for the treatment of lower-extremity wounds with exposed bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(5):1184–1191. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200110000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleischmann W, Russ M, Marquardt C. Closure of defect wounds by combined vacuum sealing with instrumental skin expansion. Unfallchirurg. 1996;99(12):970–974. doi: 10.1007/s001130050082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horch RE, Münchow S, Dragu A. Erste Zwischenergebnisse der Perfusionsbeeinflussung durch Prevena: gewebsperfusionsmessung. Z Wundheilung. 2011;A 16:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedmond BT, Kortesis B, Punger K, Simpson J, Argenta J, Kulp B, Morykwas M, Webb LX. The use of negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the temporary treatment of soft-tissue injuries associated with high-energy open tibial shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(1):11–17. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31802cbc54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehner B, Bernd L. V.A.C.-instill therapy in periprosthetic infection of hip and knee arthroplasty. Zentralbl Chir. 2006;131(Suppl 1):S160–S164. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-921513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brem MH, Blanke M, Olk A, Schmidt J, Mueller O, Hennig FF, Gusinde J. The vacuum-assisted closure (V.A.C.) and instillation dressing: limb salvage after 3 degrees open fracture with massive bone and soft tissue defect and superinfection. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111(2):122–125. doi: 10.1007/s00113-007-1360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gesslein M, Horch RE. Interdisciplinary management of complex chronic ulcers using vacuum assisted closure therapy and "buried chip skin grafts". Zentralbl Chir. 2006;131(Suppl 1):S170–S173. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-921460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loos B, Kopp J, Kneser U, Weyand M, Horch RE. The importance of vacuum therapy in the treatment of sternal osteomyelitis from the plastic surgeons point of view. Zentralbl Chir. 2006;131(Suppl 1):S124–S128. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-921425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stannard JP, Volgas DA, Stewart R, McGwin G, Jr, Alonso JE. Negative pressure wound therapy after severe open fractures: a prospective randomized study. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(8):552–557. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181a2e2b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischmann W, Strecker W, Bombelli M, Kinzl L. Vacuum sealing as treatment of soft tissue damage in open fractures. Unfallchirurg. 1993;96(9):488–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horch RE, Gerngross H, Lang W, Mauckner P, Nord D, Peter RU, Vogt PM, Wetzel-Roth W, Willy C. Indications and safety aspects of vacuum-assisted wound closure. MMW Fortschr Med. 2005;147(Suppl 1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willy C, Thun-Hohenstein H, Lubken F, Weymouth M, Kossmann T, Engelhardt M. Experimental principles of the V.A.C.-therapy—pressure values in superficial soft tissue and the applied foam. Zentralbl Chir. 2006;131(Suppl 1):S50–S61. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-921421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stannard JP, Atkins BZ, O'Malley D, Singh H, Bernstein B, Fahey M, Masden D, Attinger CE. Use of negative pressure therapy on closed surgical incisions: a case series. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2009;55(8):58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan M, Daly D, Stemkowski S. Early intervention of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum-assisted closure in trauma patients: impact on hospital length of stay and cost. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2009;22(3):128–132. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000305451.71811.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]