Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the effect of bilateral total hip replacement (THR) for patients with ankylosed hip joints caused by late ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and to discuss its related pre- and postoperative problems.

Methods

Data of 12 patients with ankylosed hip joints caused by late AS who underwent THR (24 hips) were reviewed. Each patient had both hips replaced at the same time. We assessed joint pain, range of motion (ROM) and Harris hip score (HHS) to determine postoperative results.

Results

Mean follow-up was 4.2 years; all hip-joint function improved, and flexion deformity was corrected. Flexion ranges were 75–105°(average 84. 4°) extension 10°~20°(average 18. 7°). HHS ranged from 15.21 points preoperation to 86.25 points postoperation. No patient experienced hip pain postoperatively, and presurgery knee and lower back pain were clearly relieved postoperatively.

Conclusion

Bilateral THR is an effective treatment for the ankylosed hip joint caused by late ankylosing spondylitis. When considering this procedure, attention to related pre- and postoperative problems must be considered.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) plays a central role in a group of interrelated spondyloarthropathies [1]. The literature reports that 30–50% of AS typically involves the hips, and among those with affected hips, 90% present with bilateral hip ankylosis [2]. The combination of a stiff thoracolumbar spine and hip can cause severe disability in function, which greatly affects these young patients physically and economically. Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is the most common surgical intervention for such patients[3] . This study analysed the effect of bilateral THR for patients with ankylosed hip joints caused by late AS and reviewed the operative strategy.

Materials and methods

From August 2000 to August 2006, 24 hips of 12 patients with bilateral ankylosis underwent THA by a single surgeon at our institute. Ankylosis of the hip was defined by physical examination as a total loss of hip motion. Only bony ankylosis cases were included. There were eight men and four women with an average age of 36.5 (range 26–50) years. All patients had bilateral bony ankylosis with 0° range of motion (ROM). Average angle of hip flexion deformity was 18.7° ( six hips 20–30°, ten hips 10–20°, eight hips <10°). Mean duration of ankylosis before conversion was 12 (range 2–20) years. Initial diagnosis in all patients was AS. Preoperatively, patients could not walk to the bathroom or leave their home unless in a wheelchair. Eight had progressive disabling pain in the lower back or knee, loss of function caused by immobility or malposition of both hips, severe limping and walking disability. Preoperatively, X-ray templating was undertaken to carefully plan anatomical reconstruction and assess the use of the most appropriate approach depending on patient anatomy. All patients received bilateral THA in a single day. Based on the deformity, we chose the worst hip to replace first, considering: (1) hips with external rotation deformity, in which visualising the femoral neck through the the posterior approach was difficult; (2) patients with sagittal pelvic malrotation; hips with flexion deformity fused with a relatively bigger angle in which soft tissues release need to be performed

The surgical technique was as follows: Incision was via the posterolateral approach. After detaching the external rotators, the femoral-neck resection line was identified by approaching the inferior neck and locating the pubofemoral arch and lesser trochanter. Using a two-step system (Fig. 1), at an angle of 45°at the juncture of the femoral head and neck, the femoral neck was cut. Secondly, the joint was dislocated and the remaining portion of the femoral neck removed. The articular capsule and osteophytes were thoroughly excised to sufficiently expose the acetabulum. No trochanteric osteotomy was performed. Acetabular preparation started with removal of the remaining femoral-head piecemeal. Reaming with sequentially larger reamers was then done in the medial direction, as it is difficult to identify the location of the original joint plane and ensure optimum positioning of components. In our study, we used the foveal soft tissue as an indication for locating the original joint plane. Although hips had bony fusion, there remained incomplete gray ossifying cartilage at the location of the original joint plane, which also helped to identify the location of the original joint plane. In some instances, intraoperative radiographs were taken to identify the original joint plane, which may have been useful (Fig. 2). We used a transverse acetabular ligament as a guide to appropriate acetabular prosthesis anteversion and the lesser trochanter as a guide to appropriate femoral prosthesis anteversion. According to the specific hip deformity, we determined the prosthesis insertion angle and performed a trial reduction to check stability in all directions, correction of the fixed deformity and limb length. After this trial reduction, definitive components were implanted. In all hips, short external rotator muscles were closed after the surgical procedure and the wound closed without a drain. All patients received uncemented THAs [a Metabloc femoral component with a 28-mm femoral-head diameter and an Allofit acetabular cup component with polyethylene acetabular lining component (Zimmer)]

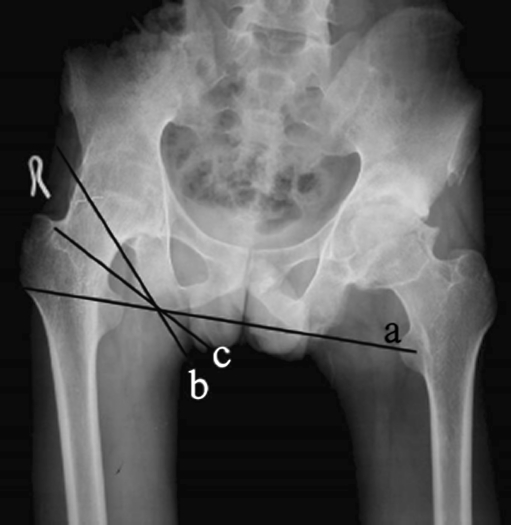

Fig. 1.

Delineation of two-step system: line of two ischial tuberosities, b osteotomy line in the first step, c osteotomy line in the second step

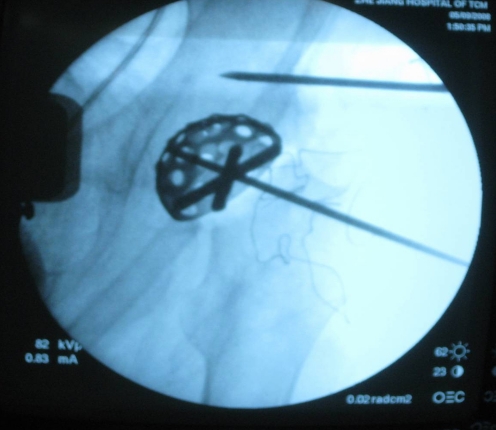

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative radiographs help identify the original joint plane

Prophylactic antibiotics were routinely given, with one dose intraoperatively and continued for three days postoperatively. Patients were usually allowed to walk with support after three days, and full weight bearing was permitted after ten weeks. No prophylactic anti-inflammatory drugs were used to prevent heterotopic ossification. The average follow-up period was 4.2 (range one to six) years. Clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed at six weeks, three months, six months and one year, then annually or biannually. Clinical results were evaluated by calculating HHS and ROM pre- and postoperatively. Student's t-test was used for analysis of Harris hip scores and range of motion. Statistical significance was measured at P = 0.01 for all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software.

Results

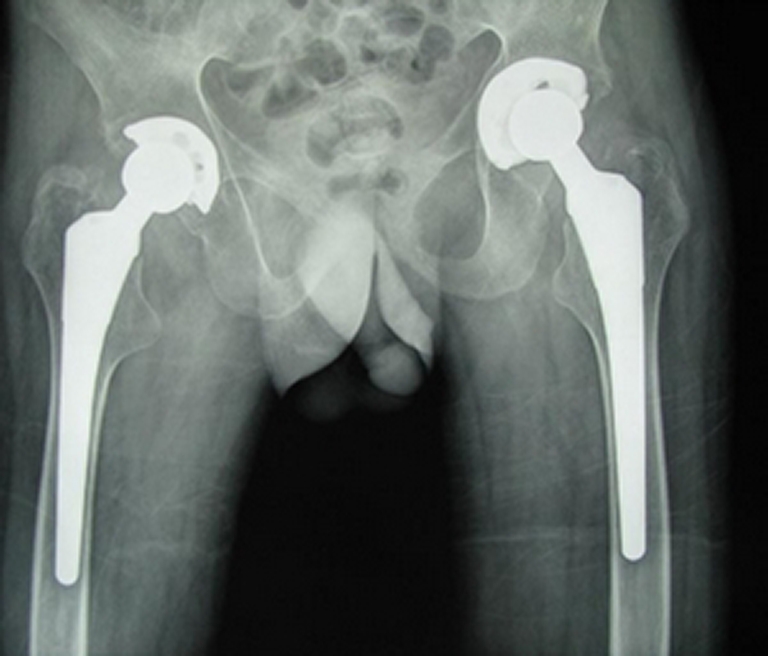

Average HHS increased from 15.21 (range 10–42) points preoperatively to 82.65 (range 72–96) points at final follow-up. Average hip ROM in flexion was 84.4°(range 75°–105°) and extension was18.7° (range 10°–20°). All the data pre- and postoperatively showed remarkable difference according to Student’s t test (p < 0.01, detailed in Table 1). Ten patients were able to walk without support at final follow-up. Eight patients had preoperative low back pain; three of those patients had no back pain postoperatively, and the other five had residual low back pain that was more tolerable than the preoperative pain. In eight patients with preoperative knee pain, six showed improvement. One patient with persistent knee pain needed total knee arthroplasty and the other is awaiting this operation. All patients were subjectively satisfied with bilateral conversion of their ankylosed hips to THA (Figs. 3 and 4)

Table 1.

Hip range of motion and Harris hip score (x ± s) (p < 0.01)

| Time | No. | Flexion (°) | Extension (°) | Harris hip score (points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 12 | 0. 00 ± 0. 00 | 8. 63 ± 1. 49 | 15. 21 ± 1. 52 |

| Postoperative | 12 | 84. 41 ± 4. 16 | 18. 72 ± 2. 13 | 82. 65 ± 4. 77 |

Fig. 3.

Preoperative anteroposterior (AP) radiograph showing ankylosed hip present for 5 years

Fig. 4.

Two years after operation, anteroposterior radiograph showing good prosthesis fixation

Complications were few. Osteolysis due to polyethylene wear was found in two hips, both of which had osteolysis of the acetabulum. Alendronate sodium tablets were prescribed to inhibit the process. No stem was loose at final follow-up in any patient. A femoral fracture occurred in two hips during stem implantation, and circumferential wiring was required. All these intraoperative fractures healed without problem. Heterotopic ossification developed in three hips (12.5%), with Brooker type 1 ossification in two and type 2 ossification in one. Transient femoral nerve palsy was detected in one hip, but this recovered spontaneously after three months. There was no postoperative dislocation or infection.

Discussion

Conversion of ankylosed hips to THA are difficult procedures, although several reports have demonstrated excellent survivorship with high patient satisfaction [2, 4, 5]. However, to the best of our knowledge, few reports have focused specifically on bilateral conversion of ankylosed hips. In this study, the overall clinical result was considered good as reflected by a final average HHS of 82.65 points. There was no reoperation (in particular no revision) in the 24 hips. Relief of low back pain and knee pain was evident in most patients. Final ROM was less satisfactory than achieved by THA overall. A few complications were observed, but most were minor. Although this study outlined a small number of patients treated with this procedure, we emphasise a number of factors evident in our experience that we believe are useful when considering these procedures.

We found preoperative planning to be of value. It allowed consideration of offset and leg-length inequality. We believe that accurate reconstruction of the axes gives the previously weak abductor musculature the best chance of strengthening [6]. In some ankylosed hips, it is difficult to expose the femoral head and neck, especially in cases of flexion with external rotation deformity. If an in situ osteotomy of the femoral neck was performed, it might cut into the greater trochanter or divide the posterior acetabular wall during neck resection. Therefore, many researchers [7–10] recommend the operation be carried out in the lateral position using a standard transtrochanteric approach. In our study, we found that using the two-step system to remove the femoral head was feasible. We found that most hips had flexion and adduction deformity, and it was easily to exposure anatomical structures such as the femoral head and neck posterior border of the acetabulum and ischial tuberosity. Also, exposure of the lesser trochanter of the femur when the posterolateral approach was used was beneficial during the first step in femoral-neck osteotomy. Even in hips with external rotation deformity, the first step in femoral-neck osteotomy could be facilitated by identifying the lesser trochanter or, under fluoroscopic guidance, identifying the juncture of femoral head and neck. After the remnant of the femoral neck is removed, the anterior aspect of the articular capsule is conveniently exposed, so we did not perform a trochanteric osteotomy. Leg-length correction is limited due to the potential risk of damage to the sciatic nerve. Maximum length that can be safely gained at the time of THR is no more than 4 cm [11, 12]. We recommend that leg length be increased, and we advise the use of some form of intraoperative measuring system to facilitate this aim.

We found it difficult to accord with the nature of the conversion procedure for ankylosed hips, especially insertion of the prosthesis. In the routine THA, the acetabular cup is inserted with an anteversion of 20° and fixed at 45°inclination, and the femoral prosthesis is inserted with an anteversion between 10° and 20°. In cases of bilateral hip ankylosis, there was always deformity, such as flexion, adduction or abduction deformity, internal or external rotation deformity and so on. Although such deformities can be rectified, ROM does not recover dramatically after conversion and will still affect positioning. We emphasise the technically demanding nature of the conversion procedure for ankylosed hips in order to reduce the risk of dislocation. Tang et al. [13] hypothesised that pelvic malrotation in the sagittal plane, which is common in AS patients, can cause errors in cup positioning. They used three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) reconstruction to verify the idea. Two methods of cup insertion were simulated and compared: a method mimicking genuine surgery (anatomical positioning) and one that compensated for the sagittal pelvic malrotation (functional positioning). Sagittal pelvic malrotation >20°, if ignored, resulted in a cup with an anteversion >30° and an inclination >55°. Half of the cup surface was not in contact with host bone when the cup position was maintained at 20° anteversion and 45° inclination in a patient with 50° sagittal pelvic malrotation. The usual method of cup positioning may need to be modified in patients with sagittal pelvic malrotation in order to maintain the desired cup position. For each 10° of sagittal pelvic malrotation >20°, the cup needs to be positioned so that it is 5° less inclined and anteverted. To minimise the risk of anterior dislocation of the prosthesis, the authors suggest that spinal osteotomy be considered before THA in patients with severe spinal and hip deformities [5]. We agree with the authors’ findings and specifically caution against the risk of anterior dislocation of the hip in these cases. In our study, we regulated the prosthesis insertion angle according to the specific deformity. We inserted the prosthesis as a routine THA when it was a simple flexion deformity; if combined with limb internal rotation, we reduced the anteversion angle of the acetabular cup and increased the anteversion angle of the femoral prosthesis when inserting the prosthesis. In contrast, we increased the anteversion angle of the acetabular cup and reduced the anteversion angle of the femoral prosthesis or kept the anteversion angle of the femoral prosthesis at 0° when it was combined with external rotation deformity of the limb. When combined with hip adduction deformity, we also removed some contracted adductors and reduced the acetabular cup inclination angle, which may reduce hip function but will enhance stability.

Careful attention must be paid to technical details during surgery. One difficulty with the procedure is to identify the location of the original joint plane. We found foveal soft tissue to be an indication of the location of the original joint plane. Although hips had bony fusion, there always remained incomplete gray ossifying cartilage at the location of the original joint plane, which also helped us identify the location of the original joint plane. Intraoperative radiographs were taken to identify the original joint plane in some cases (Fig. 2). Acetabular osteoporosis during acetabular reaming was often encountered, which is a common finding in AS [14].To deal with this problem, we: (1) identified the location of the original joint plane and retained as much as possible of the subchondral bone, as overreaming may compromise the acetabular bone stock; (2) often used the counterrotation technique of the reamer, which prevents overreaming the bone of the acetabular base; (3) used impaction bone grafting or bulk femoral allografts to obtain stability of the acetabular cups if overreaming occurred. In addition, there are several details to which close attention should be paid when operations were carried out with these seriously osteoporotic patients: (1) Avoid brute force Intraoperatively when dislocating, reducing and rotating the hips. To prevent femoral fractures, in some hips with severe flexion deformity, an anterior capsulotomy and soft tissue release (including the iliopsoas tendon and sartorius and rectus femoris tendons) should be performed. This not only reduces the residual flexion deformity but also creates enough interspace to insert the acetabular cup. (2) As the femoral cortical bone becomes thin, care should be taken to avoid damage to the proximal femur during reaming and broaching during insertion. Femoral fracture occurred in two hips during stem implantation, and circumferential wiring was required. (3) To acquire solid fixation, we recommend using extensively coated stems with distal fixation. Mertl P[15] distal locking stem in cases of severe bone loss during revision hip arthroplasty, which achieves an easy and strong initial fixation. (4) Exaggerated femoral anteversion is often seen in these patients. Trial reduction after positioning of the trial components to check for the stability in all directions will help minimise the dislocation rate.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this study, overall outcomes after bilateral conversion of bilateral hips with ankylosis to THA were found to be favourable, and patients were highly satisfied with the procedure. When considering these procedures, much attention must be paid to related pre- and postoperative problems.

References

- 1.Calin A. Ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheum Dis. 1985;111:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi AB, Markovic L, Hardinge K, Murphy JCM. Total hip arthroplasty in ankylosing spondylitis: an analysis of 181 hips. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:427–433. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.32170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Weidong Xu, Ling Xu, Liang Z. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty for ankylosing spondylitis. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1285–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeney S, Gupta R, Taylor G, Calin A. Total hip arthroplasty in ankylosing spondylitis: outcome in 340 patients. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1862–1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang WM, Chiu KY. Primary total hip arthroplasty in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:52–58. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(00)91155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilgus DJ, Amstutz HC, Wolgin MA, Dorey FJ. Joint replacement for ankylosed hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YH, Oh SH, Kim JS, Lee SH. Total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of osseous ankylosed hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;414:136–148. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000081935.75404.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamadouche M, Kerboull L, Meunier A, Courpied JP, Kerboull M. Total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of ankylosed hips: a five to twenty-one-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:992–998. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YL, Shin SI, Nam KW, Yoo JJ, Kim YM, Kim HJ. Total hip arthroplasty for bilaterally ankylosed hips. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1037–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhan S, Eachempati KK, Malhotra R. Primary cementless total hip arthroplasty for bony ankylosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanssen AD, Mariani EM, Kavanagh BF, Coventry MB. Resection arthroplasty (Girdlestone Proceedure), nerve palsies, limb length inequality, and osteolysis following total hip arthroplasty. In: Morrey BF, editor. Joint Replacement Arthroplasty. New York: Churchill Livingsone; 1991. pp. 897–905. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmalzried TP, Amstutz HC, Dorey FJ. Nerve palsy associated with total hip replacement: Risk factors and prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1074–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang WM, Chiu KY, Kwan MF, Ng TP. Sagittal pelvic mal-rotation and positioning of the acetabular component in total hip arthroplasty: three-dimensional computermodel analysis. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:766–771. doi: 10.1002/jor.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vosse D, Vlam K. Osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:S62–S67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mertl P, Philippot R, Rosset P, Migaud H, Tabutin J, Velde D. Distal locking stem for revision femoral loosening and peri-prosthetic fractures. Int Orthop. 2011;35:275–282. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1182-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]