Abstract

A central question of marine ecology is, how far do larvae disperse? Coupled biophysical models predict that the probability of successful dispersal declines as a function of distance between populations. Estimates of genetic isolation-by-distance and self-recruitment provide indirect support for this prediction. Here, we conduct the first direct test of this prediction, using data from the well-studied system of clown anemonefish (Amphiprion percula) at Kimbe Island, in Papua New Guinea. Amphiprion percula live in small breeding groups that inhabit sea anemones. These groups can be thought of as populations within a metapopulation. We use the x- and y-coordinates of each anemone to determine the expected distribution of dispersal distances (the distribution of distances between each and every population in the metapopulation). We use parentage analyses to trace recruits back to parents and determine the observed distribution of dispersal distances. Then, we employ a logistic model to (i) compare the observed and expected dispersal distance distributions and (ii) determine the relationship between the probability of successful dispersal and the distance between populations. The observed and expected dispersal distance distributions are significantly different (p < 0.0001). Remarkably, the probability of successful dispersal between populations decreases fivefold over 1 km. This study provides a framework for quantitative investigations of larval dispersal that can be applied to other species. Further, the approach facilitates testing biological and physical hypotheses for the factors influencing larval dispersal in unison, which will advance our understanding of marine population connectivity.

Keywords: propagule dispersal, dispersal kernel, parentage analyses, population connectivity, reserve design, marine fish

1. Introduction

Understanding patterns of larval dispersal is a major goal of twenty-first century marine ecology [1–4]. These patterns determine the probability of larval exchange, or connectivity, among populations [1,5]. Population connectivity, in turn, has major consequences for all aspects of an organism's biology [6], from individual behaviour [7,8] to metapopulation dynamics [9,10], and from evolution within metapopulations [11,12] to the origin and extinction of species [13,14]. Further, understanding patterns of larval dispersal is critical for the design of effective networks of marine reserves—vital tools in the development of sustainable fisheries [15–20].

A fundamental question of marine larval dispersal and population connectivity is: how does the probability of larval exchange vary as a function of distance between populations? Coupled biophysical models predict that the probability of successful dispersal declines dramatically over 10–100 km for a variety of species [20–24]. Estimates of genetic isolation-by-distance provide indirect support for this prediction [11,12,25–27], as do demonstrations of high levels of self-recruitment to natal populations [28–32]. However, direct measures of the relationship between the probability of successful dispersal and distance between populations are lacking. Direct measures, obtained by tracing individual larvae back to their parents using molecular markers, will generate new insights and enable us to test predictions of biophysical models, just as they have been carried out in terrestrial systems [33–37].

The clown anemonefish (Amphiprion percula) offers a tractable system to test directly the hypothesis that the probability of successful dispersal declines as a function of distance between populations. Amphiprion percula live in small breeding groups that inhabit sea anemones [38–41]. These groups can be considered populations within a metapopulation (sensu [42]). In any given metapopulation of A. percula, all anemones can be located and all fish can be genotyped [43,44]. These data can be used to generate the observed dispersal distance distribution (the distribution of distances between recruits and their parents; figure 1a) and the expected dispersal distance distribution (the distribution of distances between each and every anemone in the metapopulation; figure 1b), which can be compared statistically [33,35,43]. Here, we use such data from a metapopulation of A. percula to test two hypotheses: (i) the observed distribution of dispersal distances will differ from the expected distribution of dispersal distances and (ii) the probability of successful dispersal will decline as a function of distance between populations.

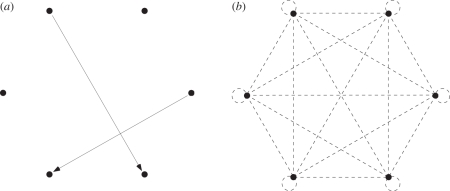

Figure 1.

Dispersal distances in a hypothetical metapopulation composed of six populations (black circles). (a) Observed dispersal distances are the distances between recruits and their parents in the metapopulation—there are two observed dispersal distances in this metapopulation (solid lines). (b) Expected dispersal distances are the distances between each and every population in the metapopulation—there are 6 × 6 = 36 expected dispersal distances in this metapopulation (dashed lines). In a well-mixed metapopulation, the observed distribution of dispersal distances will be the same as the expected distribution of dispersal distances.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study population

This study was conducted using a metapopulation of the clown anemonefish, A. percula (Family: Pomacentridae), at Kimbe Island, Papua New Guinea—an area of approximately 1 km square [44]. All fieldwork was conducted using self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) at depths of up to 15 m. In December 2004, 275 anemones occupied by A. percula were located. At this site, all anemones were occupied, consistent with observations at other sites in Papua New Guinea [38,40]. All anemones were mapped [44] and their depths were measured. The two largest fish (i.e. potential breeders [39,45]) in each anemone were captured, fin-clipped and returned to their anemone. In December 2004 and April 2005, all juvenile fish (i.e. recent recruits [38,46]) in each anemone were collected. Based on otolith increment counts, these recruits were no more than four months old (N. Raventos 2008, unpublished data). Thus, counts of dispersal events and probabilities of dispersal, reported below, represent counts and probabilities for a period of approximately eight months.

(b). Observed dispersal distances

To generate an observed distribution of dispersal distances, we traced recruits back to their parents using nuclear DNA markers. Five hundred and six breeders and 469 new recruits were genotyped at 16 highly polymorphic microsatellite loci that satisfied Hardy–Weinberg assumptions [44]. Parentage analyses, implemented using FAMOZ [17,18], were used to assign recruits to parents around Kimbe Island. One hundred and six recruits to the island were assigned to parents from the island [44]. Some dispersal events will have been missed because settlers can be driven from the anemone within hours of their arrival [38,47]. Individuals that we trace back to their parents are those individuals that managed to disperse and recruit to an anemone. For brevity, we define the combination of dispersal and recruitment as ‘successful dispersal’. Tracing recruits back to their parents and estimating the distance between anemones (see below) enabled us to generate an observed dispersal distance distribution (figure 2).

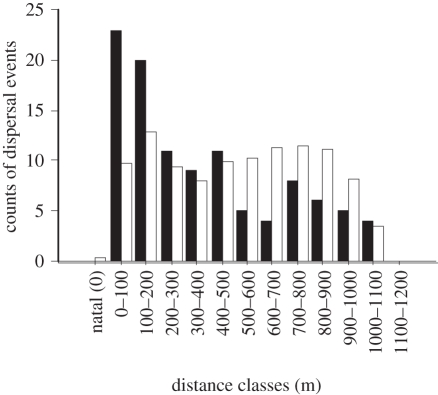

Figure 2.

Dispersal distance distributions in a metapopulation of the clown anemonefish Amphiprion percula: observed dispersal distance distribution, determined by tracing recruits back to their parents using molecular markers (black bars, n = 106); expected dispersal distance distribution determined by estimating the distance between each and every anemone in the metapopulation (white bars, n = 75 635 scaled to n = 106). To facilitate visualization of the data, observed and expected dispersal distances are assigned to 100 m bins. Counts of successful dispersal are the counts over approximately eight months.

(c). Expected dispersal distances

To generate an expected distribution of dispersal distances, we estimated the distance between each and every anemone in the metapopulation. The x-, y- and z-coordinates of each anemone were entered into a database. These coordinates were then used to estimate the shortest in-water distance between each and every anemone. Further, these coordinates were used to estimate the direction and depth change between each pair of anemones, so that we could control for these factors in our statistical analysis (see below). In this metapopulation of 275 anemones, there are 2752 = 75 625 expected dispersal distances. However, we exclude 275 distances that involve return to the natal anemone because A. percula do not form kin groups [43] and larvae actively avoid settling with kin [48]. Estimating the distance between each and every anemone in the metapopulation enabled us to generate an expected dispersal distance distribution (figure 2).

(d). Statistical analyses

We tested the hypotheses that (i) the observed distribution of dispersal distances will differ from the expected distribution of dispersal distances and (ii) the probability of successful dispersal will decline as a function of distance between populations, using a logistic model (JMP v. 8.0.1). The probability of successful dispersal between anemones (0 or 1) was used as the dependent variable, whereas distance (continuous), direction (categorical) and depth change (continuous) between anemones were used as independent variables. There was never more than one dispersal event between any two anemones, so there is no loss of numeric information when using the binary response variable. This approach enabled us to test for the effect of one variable (e.g. distance) while controlling statistically for the effect of other variables (e.g. direction and depth change), and explore the effect of interactions between variables. Independent variables were removed from the model in a backward stepwise fashion if they did not have a significant effect. We confirmed that the model generated in this way was the same as the model generated using a forward stepwise approach.

3. Results

The observed dispersal distance distribution was significantly different from the expected dispersal distance distribution (whole model Chi-square test: χ2 = 31.8, d.f. = 2, p < 0.0001, r2 = 0.02). The probability of successful dispersal between populations declined as a function of distance between populations: larvae were five times as likely to successfully disperse 1 m as they were to successfully disperse 1 km (table 1 and figure 3). The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the model parameter estimates indicate that larvae were between 2.5 and 10 times more likely to disperse 1 m than they were to disperse 1 km.

Table 1.

Probability of successful dispersal between populations in relation to multiple independent variables. Summary of the results of a stepwise logistic model that investigated the effects of distance, direction, depth change and all interactions.

| parameter | estimate | lower 95% | upper 95% | χ2 | prob > χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | −5.8880 | −6.2263 | −5.5717 | 1246.00 | <0.0001 |

| depth | −0.0839 | −0.1374 | −0.0299 | 9.36 | 0.0022 |

| distance | −0.0016 | −0.0023 | −0.0009 | 21.31 | <0.0001 |

Figure 3.

Probability of successful dispersal between populations as a function of distance between populations, within a metapopulation of the clown anemonefish Amphiprion percula. Solid line represents the relationship between probability of successful dispersal and distance between populations estimated from a logistic model (table 1). Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around this estimated relationship (table 1). Reported probability of successful dispersal is the probability of successful dispersal over approximately eight months.

The probability of successful dispersal between populations was not related to the direction between populations. That is to say, at this spatial scale (up to 1 km) and this temporal resolution (lumping dispersal events that occurred over four months), there was no consistent bias in the direction of dispersal. The probability of successful dispersal between populations was, however, related to the difference in depth between populations: larvae were more likely to recruit to populations deeper than the population of their birth, than they were to recruit to populations shallower than the population of their birth (table 1).

4. Discussion

Quantifying how the probability of larval exchange varies as a function of distance between populations remains a daunting logistical challenge for marine ecologists. Here, we take on this challenge, using data from a population of the clown anemonefish, A. percula, at Kimbe Island, in Papua New Guinea. Amphiprion percula live in small breeding groups that inhabit sea anemones, and these groups can be thought of as populations within a metapopulation. We used the x- and y-coordinates of each anemone to estimate the distance between each population and determine the expected distribution of dispersal distances; we traced recruits back to their parents using parentage analyses to determine the observed distribution of dispersal distances. We used these data to test two hypotheses: (i) the observed distribution of dispersal distances will differ from that expected by random chance and (ii) the probability of successful dispersal will decline as a function of distance between populations.

(a). Dispersal with respect to random chance

We show that the probability of successful dispersal between populations is not random: the probability of successful dispersal varies as a function of distance and depth displacement. While significant, the whole model explains only a small proportion of the total variation in the data. This is probably because we are trying to explain which of 75 000+ possible dispersal trajectories are used with only 106 observed dispersal events. Presumably, there were many dispersal trajectories not used simply because our observed number of dispersal events was low. We anticipate that increasing sample size will increase the proportion of the variation explained. Furthermore, in this study, we are investigating the pattern of dispersal in three-dimensional space, without investigating any causal agents. We know that behavioural and physical processes influence the probability that a particular dispersal trajectory will be taken. Incorporating these factors into the model in the future will, probably, improve the proportion of the variation explained beyond the baseline set here.

(b). Dispersal with respect to distance

Most strikingly, we found that the probability of successful dispersal declined significantly as the distance between populations increased. Larvae are five times more likely to disperse 1 m than they are to disperse 1 km. The 95% CIs show that larvae are 2.5–10 times more likely to disperse 1 m than they are to disperse 1 km. This suggests that the A. percula dispersal kernel is a unimodal leptokurtic distribution with a peak close to source, analogous to the majority of terrestrial seed dispersal kernels [6].

We note that many dispersal events will have gone undocumented because residents sometimes drive settlers from anemones within hours of arrival [38,47] and we were unable to sample at this temporal resolution. Given this limitation, there are two plausible alternative hypotheses for the relationship that we observe between the probability of successful dispersal and distance: (i) the probability of dispersal itself decreases as a function of distance and (ii) the probability of recruitment decreases with distance. We favour the former hypothesis because it is difficult to envisage why recruitment would vary so dramatically with distance at this small spatial scale. Furthermore, if the probability of recruitment were to decline with distance, then this would create natural selection for behaviours that facilitate larvae dispersing short distances.

To the best of our knowledge, these are the first quantitative estimates of population connectivity parameters and associated error, based on direct measures of larval dispersal, in the marine environment. Such data hold the key to fisheries management and the design of effective networks of marine reserves [1]. The rapid decline in the probability of successful dispersal with distance, if it were also found in other species, would have significant implications for the spacing of marine protected areas and the scale of fisheries management.

(c). Dispersal with respect to direction and depth

In contrast to the effect of distance, we found that the probability of successful dispersal did not vary consistently with direction between populations. This result is perhaps surprising given that currents are predicted to have strong effects on the probability of dispersal [20–23]. It should be noted that there was a mismatch between the temporal resolution at which our data were collected (we lumped dispersal events that occurred over an eight-month period) and the temporal scales at which currents around Kimbe Island are likely to vary. Having said that, for clownfish in Kimbe Bay, it is possible that currents do not play a significant role in determining the pattern of dispersal at this small spatial scale (less than 1 km). We expect that currents will play a more significant role in determining the pattern of dispersal at larger spatial scales.

Unexpectedly, we found that the probability of successful dispersal varied with depth displacement between populations. Larvae were more likely to recruit to populations deeper than the population of their birth than they were to recruit to populations shallower than the population of their birth. It is beyond the scope of this paper to speculate on the causes of this pattern. Further work is clearly warranted to test alternative biological (proximate and ultimate) and physical hypotheses for the causes of the pattern.

(d). Future directions

We have used the clownfish (A. percula) as a model to develop a framework for quantitative investigations of marine larval dispersal and population connectivity. In the future, we will use this approach to investigate spatial and temporal variation in the pattern of dispersal in A. percula. We suggest that the approach could also be used to investigate the pattern of dispersal in other species and to test the generality of the findings emerging from A. percula. One challenge in doing this would be tracing sufficient numbers of recruits back to their parents, but similar levels of self-recruitment to those found in A. percula have been recorded in other damselfishes [29], wrasses [30], butterflyfishes [28], triple-fin blennies [49] and a rapidly increasing list of reef fish species [50], suggesting that this would be possible. Furthermore, many of these species exhibit quite specialized breeding and recruitment sites and, with appropriate sampling, it would be possible to generate the observed and expected distributions of dispersal trajectories that hold the key to the analysis employed here. Because A. percula is sometimes regarded as being unique, we consider that testing the generality of the findings emerging from A. percula should be made a priority.

Our study also provides a framework for testing alternative hypotheses regarding the biological and physical factors that might influence marine larval dispersal and population connectivity. Considering biological factors, in A. percula, male growth and female body size influence the numbers of eggs produced in each population [39,45], whereas anemone saturation and reef type influence the likelihood of recruitment to each population [38,51]. It should be relatively straightforward to include these factors as additional independent variables in the logistic model and also determine whether they influence the probability of successful dispersal. Considering physical factors, high-resolution biophysical models predict connectivity based on the probability that water parcels from one location are advected to another location [21–24]. It should be possible to include the physical connectivity estimates derived from these models as an additional independent variable in the logistic model and determine the extent to which they explain population connectivity. By developing a framework for testing biological and physical hypotheses in unison, this study lays the foundation for a deeper understanding of marine larval dispersal and population connectivity.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, Coral Reef Initiatives for the Pacific (CRISP), Global Environmental Facility CRTR Connectivity Working Group, National Science Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, Total Foundation, James Cook University, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Boston University. We thank Steven Bogdanowicz, Cassidy D'Aloia, Cristina García, José Godoy, Richard Harrison, Pedro Jordano, Amy McCune, Elizaveta Pachepsky and Colleen Webb for helpful comments and discussion; Glenn Almany, Michael Berumen, Caroline Hervet, Vanessa Messmer, Craig Syms and Maya Srinivasan for providing assistance in the field; the Mahonia Na Dari Research and Conservation Centre, Walindi Plantation Resort, The Nature Conservancy and the crew of FeBrina for providing essential logistical support; and the traditional landowners for allowing us access to their reefs.

References

- 1.Botsford L. W., White J. W., Coffroth M. A., Paris C. B., Planes S., Shearer T. L., Thorrold S. R., Jones G. P. 2009. Connectivity and resilience of coral reef metapopulations in marine protected areas: matching empirical efforts to predictive needs. Coral Reefs 28, 327–337 10.1007/s00338-009-0466-z (doi:10.1007/s00338-009-0466-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowen R. K., Gawarkiewicz G., Pineda J., Thorrold S. R., Werner F. E. 2007. Population connectivity in marine systems: an overview. Oceanography 20, 14–21 10.5670/oceanog.2007.26 (doi:10.5670/oceanog.2007.26) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kritzer J. P., Sale P. F. 2004. Metapopulation ecology in the sea: from Levin's model to marine ecology and fisheries science. Fish Fisheries 5, 131–140 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2004.00131.x (doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2004.00131.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner R. R., Cowen R. K. 2002. Local retention of production in marine populations: evidence, mechanisms and consequences. Bull. Mar. Sci. 70, S245–S249 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowen R. K., Gawarkiewicz G., Pineda J., Thorrold S., Werner F. 2002. Population connectivity in marine systems. Report of a workshop to develop science recommendations for the National Science Foundation, 4–6 November 2002 Colorado: Durango; (See http://www.nsf.gov/geo/oce/pubs/PopComFinalReport1.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin S. A., Muller-Landau H. C., Nathan R., Chave J. 2003. The ecology and evolution of seed dispersal: a theoretical perspective. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 575–604 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132428 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132428) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnstone R. A. 2008. Kin selection, local competition, and reproductive skew. Evolution 62, 2592–2599 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00480.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00480.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokko H., Lundberg P. 2001. Dispersal, migration, and offspring retention in saturated habitats. Am. Nat. 157, 188–202 10.1086/318632 (doi:10.1086/318632) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botsford L. W., Hastings A., Gaines S. D. 2001. Dependence of sustainability on the configuration of marine reserves and larval dispersal distances. Ecol. Lett. 4, 144–150 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00208.x (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00208.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastings A., Botsford L. W. 2006. Persistence of spatial populations depends on returning home. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6067–6072 10.1073/pnas.0506651103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0506651103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purcell J. F. H., Cowen R. K., Hughes C. R., Williams D. A. 2006. Weak genetic structure indicates strong dispersal limits: a tale of two coral reef fish. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1483–1490 10.1098/rspb.2006.3470 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3470) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor M. S., Hellberg M. E. 2003. Genetic evidence for local retention of pelagic larvae in a Caribbean reef fish. Science 299, 107–109 10.1126/science.1079365 (doi:10.1126/science.1079365) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jablonski D. 1986. Larval ecology and macroevolution in marine invertebrates. Bull. Mar. Sci. 39, 565–587 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lester S. E., Ruttenberg B. I. 2005. The relationship between pelagic larval duration and range size in tropical reef fishes: a synthetic analysis. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 585–591 10.1098/rspb.2004.2985 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gell F. R., Roberts C. M. 2003. Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 448–455 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00189-7 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00189-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sala E., Aburto-Oropeza O., Paredes G., Parra I., Barrera J. C., Dayton P. K. 2002. A general model for designing networks of marine reserves. Science 298, 1991–1993 10.1126/science.1075284 (doi:10.1126/science.1075284) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber L. R., Botsford L. W., Hastings A., Possingham H. P., Gaines S. D., Palumbi S. R., Andelman S. 2003. Population models for marine reserve design: a retrospective and prospective synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 13, S47–S64 10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0047:PMFMRD]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0047:PMFMRD]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber S., Chabrier P., Kremer A. 2003. FAMOZ: a software analysis using dominant, codominant and uniparentally inherited markers. Mol. Ecol. Notes 3, 479–481 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00439.x (doi:10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00439.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sale P. F., et al. 2005. Critical science gaps impede use of no-take fishery reserves. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 74–80 10.1016/j.tree.2004.11.007 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.11.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treml E. A., Halpin P. N., Urban D. L., Praston L. F. 2008. Modeling population connectivity by ocean currents, a graph-theoretic approach for marine conservation. Landscape Ecol. 23, 19–36 10.1007/s10980-007-9138-y (doi:10.1007/s10980-007-9138-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowen R. K., Lwiza K. M. M., Sponagule S., Paris C. B., Olson D. B. 2000. Connectivity of marine populations: open or closed? Science 287, 857–859 10.1126/science.287.5454.857 (doi:10.1126/science.287.5454.857) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowen R. K., Paris C. B., Srinivasan A. 2006. Scaling of connectivity in marine populations. Science 311, 522–527 10.1126/science.1122039 (doi:10.1126/science.1122039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitarai S., Siegel D. A., Watson J. R., Dong C., McWilliams J. C. 2009. Quantifying connectivity in the coastal ocean with application to the Southern California bight. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C10026. 10.1029/2008JC005166 (doi:10.1029/2008JC005166) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel D. A., Kinlan B. P., Gaylord B., Gaines S. D. 2003. Lagrangian descriptions of marine larval dispersion. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 260, 83–96 10.3354/meps260083 (doi:10.3354/meps260083) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baums I. B., Miller M. W., Hellberg M. E. 2005. Regionally isolated populations of an imperiled Caribbean coral, Acropora palmata. Mol. Ecol. 14, 1377–1390 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02489.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02489.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerlach G., Atema J., Kingsford M. J., Black K. P., Miller Sims V. 2007. Smelling home can prevent dispersal of reef fish larvae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 858–863 10.1073/pnas.0606777104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0606777104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinlan B. P., Gaines S. D. 2003. Propagule dispersal in marine and terrestrial environments: a community perspective. Ecology 84, 2007–2020 10.1890/01-0622 (doi:10.1890/01-0622) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almany G. R., Berumen M. L., Thorrold S. R., Planes S., Jones G. P. 2007. Local replenishment of coral reef fish populations in a marine reserve. Science 316, 742–744 10.1126/science.1140597 (doi:10.1126/science.1140597) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones G. P., Milicich M. J., Emslie M. J., Lunow C. 1999. Self-recruitment in a coral reef fish population. Nature 402, 802–804 10.1038/45538 (doi:10.1038/45538) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swearer S. E., Caselle J. E., Lea D. W., Warner R. R. 1999. Larval retention and recruitment in an island population of coral-reef fish. Nature 402, 799–802 10.1038/45533 (doi:10.1038/45533) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorrold S. R., Latkoczy C., Swart P. K., Jones C. M. 2001. Natal homing in a marine fish metapopulation. Science 291, 297–299 10.1126/science.291.5502.297 (doi:10.1126/science.291.5502.297) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones G. P., Planes S., Thorrold S. R. 2005. Coral reef fish larvae settle close to home. Curr. Biol. 15, 1314–1318 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.061 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.061) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García C., Jordano P., Godoy J. A. 2007. Contemporary pollen and seed dispersal in a Prunus mahaleb population: patterns in distance and direction. Mol. Ecol. 16, 1947–1955 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03126.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03126.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godoy J. A., Jordano P. 2001. Seed dispersal by animals: exact identification of source trees with endocarp DNA microsatellites. Mol. Ecol. 10, 2275–2283 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01342.x (doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01342.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jordano P., García C., Godoy J. A., García-Castaño J. L. 2007. Differential contribution of frugivores to complex seed dispersal patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3278–3282 10.1073/pnas.0606793104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0606793104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nathan R. 2006. Long-distance dispersal of plants. Science 313, 786–788 10.1126/science.1124975 (doi:10.1126/science.1124975) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nathan R., Muller-Landau H. C. 2000. Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 278–285 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01874-7 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01874-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buston P. M. 2003. Forcible eviction and prevention of recruitment in the clown anemonefish. Behav. Ecol. 14, 576–582 10.1093/beheco/arg036 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arg036) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buston P. M. 2004. Does the presence of non-breeders enhance the fitness of breeders? An experimental analysis in the clown anemonefish Amphiprion percula. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 57, 23–31 10.1007/s00265-004-0833-2 (doi:10.1007/s00265-004-0833-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elliott J. K., Mariscal R. N. 2001. Coexistence of nine anemonefish species: differential host and habitat utilization, size and recruitment. Mar. Biol. 138, 23–36 10.1007/s002270000441 (doi:10.1007/s002270000441) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fautin D. G. 1992. Anemonefish recruitment: the roles of order and chance. Symbiosis 14, 143–160 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanski I. 1998. Metapopulation dynamics. Nature 396, 41–49 10.1038/23876 (doi:10.1038/23876) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buston P. M., Bogdanowicz S. M., Wong A., Harrison R. G. 2007. Are clownfish groups composed of relatives? Analysis of microsatellite DNA variation in Amphiprion percula. Mol. Ecol. 16, 3671–3678 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03421.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03421.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Planes S., Jones G. P., Thorrold S. R. 2009. Larval dispersal connects fish populations in a network of marine protected areas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5693–5697 10.1073/pnas.0808007106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0808007106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buston P. M., Elith J. 2011. Determinants of reproductive success in dominant pairs of clownfish Amphiprion percula: a boosted regression tree analysis. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 528–538 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01803.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01803.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buston P. M. 2004. Territory inheritance in clownfish. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, S252–S254 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0156 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0156) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elliott J. K., Elliott J. M., Mariscal R. N. 1995. Host selection, location, and association behaviors of anemonefishes in field settlement experiments. Mar. Biol. 122, 377–389 10.1007/BF00350870 (doi:10.1007/BF00350870) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munday P. L., Dixson D. L., Donelson J. M., Jones G. P., Pratchett M. S., Devitsina G. V., Doving K. B. 2009. Ocean acidification impairs olfactory discrimination and homing ability of a marine fish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1848–1852 10.1073/pnas.0809996106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0809996106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carreras-Carbonell J., Macpherson E., Pascual M. 2007. High self-recruitment levels in a Mediterranean littoral fish population revealed by microsatellite markers. Mar. Biol. 151, 719–727 10.1007/s00227-006-0513-z (doi:10.1007/s00227-006-0513-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones G. P., Almany G. R., Russ G. R., Sale P. F., Steneck R. S., van Oppen M. J. H., Willis B. L. 2009. Larval retention and connectivity among populations of corals and reef fishes: history, advances and challenges. Coral Reefs 28, 307–325 10.1007/s00338-009-0469-9 (doi:10.1007/s00338-009-0469-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixson D. L., Jones G. P., Munday P. L., Planes S., Pratchett M. S., Srinivasan M., Syms C., Thorrold S. R. 2008. Coral reef fish smell leaves to find island homes. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 2831–2839 10.1098/rspb.2008.0876 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0876) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]