Abstract

The vangas of Madagascar exhibit extreme diversity in morphology and ecology. Recent studies have shown that several other Malagasy species also are part of this endemic radiation, even as the monophyly of the clade remains in question. Using DNA sequences from 13 genes and representatives of all 15 vanga genera, we find strong support for the monophyly of the Malagasy vangids and their inclusion in a family along with six aberrant genera of shrike-like corvoids distributed in Asia and Africa. Biogeographic reconstructions of these lineages include both Asia and Africa as possible dispersal routes to Madagascar. To study patterns of speciation through time, we introduce a method that can accommodate phylogenetically non-random patterns of incomplete taxon sampling in diversification studies. We demonstrate that speciation rates in vangas decreased dramatically through time following the colonization of Madagascar. Foraging strategies of these birds show remarkable congruence with phylogenetic relationships, indicating that adaptations to feeding specializations played a role in the diversification of these birds. Vangas fit the model of an ‘adaptive radiation’ in that they show an explosive burst of speciation soon after colonization, increased diversification into novel niches and extraordinary ecomorphological diversity.

Keywords: passerines, phylogeny, diversification, foraging strategies, adaptive radiation

1. Introduction

Adaptive radiation involves both taxonomic and ecological diversification in response to ecological opportunity [1], but the extent to which the process underlies the diversity of species and phenotypes across the tree of life remains poorly understood [2]. Perhaps the best-known examples of island adaptive radiation in birds are Darwin's finches (Thraupidae) and Hawaiian honeycreepers (Drepanidinae), but key tests of the adaptive radiation model have been applied to comparatively few insular avifaunas. The vangas (variously Vanginae or Vangidae) of Madagascar have been proposed to be a similar adaptive radiation [3,4], surpassing the finches in the number of species and rivalling both groups in ecomorphological disparity.

Variously a group of 15–21 species [5–7] endemic to Madagascar with one species extending into the Comoro Islands, vangas exhibit a great range of morphological, behavioural and ecological diversity. The composition of the group has long been a source of uncertainty. Evidence from recent phylogenetic investigations suggests that the subfamily is, if anything, larger and more diverse than previously recognized [3,8,9], while at the same time, others have questioned its monophyly [9,10]. The origins of this group have also been disputed [3,10,11]. Thus, while vangas are celebrated for their exceptional ecological and phenotypic diversity, we are still unsure whether the group represents an endemic in situ radiation or whether their diversity is at least partly attributable to a diverse pool of colonizing lineages.

Madagascar, being an island of continental scale and origins, has a unique biogeographic history. It has been isolated since around 84 million years ago when it split from other Gondwana fragments and was last connected to India and the Seychelles block [12]. While some endemic lineages have been proposed to be Gondwanan relicts isolated on Madagascar when the supercontinent rifted [13–15], the origins of most of the vertebrate fauna postdate these Cretaceous tectonic events [15]. Relatively few colonization events have been hypothesized to have occurred into Madagascar, with most endemic lineages proposed to be colonizers of African origin from across the Mozambique channel [15,16]. Hypotheses of modes of colonization of most terrestrial groups include rafting across the Mozambique Channel [15,17–20] or via landbridges that no longer exist [21,22], with the former receiving more support. Its proximity to Africa makes it reasonable to assume that much of the modern biota of Madagascar is derived from there, although an Asian component has been detected in some lineages [15,23–26]. Dispersals from Asia have been proposed to occur via stepping-stone islands across the Indian Ocean [25–27].

The avifauna of Madagascar is considered to be species-poor (ca 200 species) for its size [28], but about half of the species are endemic to the island. Vangas comprise one of the two larger endemic groups of passerines; the other being the Bernieridae, a newly discovered clade comprising species formerly placed in three different families [29,30]. The vangas are primarily insectivorous, although some eat fruits and even small vertebrates [28]. One of the most remarkable features of vangas is the diversity in bill size and shape that probably indicate adaptations to foraging behaviours and diets. For instance, some species probe for insects in bark, much like woodpeckers [7,28]. Earlier authors [31] hypothesized that the lack of woodpeckers in Madagascar allowed vangas to radiate into this niche.

Molecular phylogenetic studies have shown that several other species endemic to Madagascar and previously classified in other families actually belong with the vangas [3,8]. These newly classified vangas had formerly been placed with nuthatches (Hypositta), sylviid warblers (Newtonia), babblers (Mystacornis), bulbuls (Tylas) and platysteirids (Pseudobias). These results, in concert with uncertainty over vanga monophyly, pose a number of challenges to understanding the evolutionary ecological origins of Madagascar's diverse avifauna. Further, if the newly constituted Vanginae is found to be monophyletic, the morphological and ecological diversity encompassed by this radiation is significantly expanded.

In this study, we asked whether Malagasy vangas show phylogenetic and ecological patterns consistent with adaptive radiation, meaning that they are a monophyletic group exhibiting morphological and ecological diversity consistent with a model of ecological opportunity. We first tested the monophyly of the Vanginae as well as the hypothesis that vangas are an endemic in situ radiation in Madagascar. We then determined their biogeographic origins by examining their closest relatives. We studied the role of the different foraging strategies or feeding niches in driving the evolution of this group. Finally, we tested whether patterns of lineage diversification through time are consistent with a model of adaptive radiation driven by ecological opportunity [2,4,32,33], as would be expected if colonization of an area with vacant niches played a role in the evolutionary history of this group. To address temporal patterns of diversification, we introduce a method for diversification studies that can accommodate incomplete taxon sampling, regardless of whether those species have been sampled randomly or non-randomly [34].

2. Methods

(a). Phylogenetic analysis

We sampled all 15 genera and 16 out of 21 species of Vanginae (missing one species each of Xenopirostris and Calicalicus and three species of Newtonia), including all newly proposed members of this subfamily, and representatives of all potential relatives suggested by recent studies [3,10,35–38]. These included several African species of Playsteiridae and Malaconotidae, as well as Asian species proposed to be closely allied to vangas. In total, our phylogenetic dataset included 37 species, including 16 vangas, and nucleotide sequences from 13 genes, six mitochondrial and seven nuclear loci (see the electronic supplementary material for additional details).

We conducted phylogenetic analyses using maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. MP analyses were conducted in PAUP* [39] using heuristic searches to find the most parsimonious tree(s) and to calculate nodal support using bootstrap (see the electronic supplementary material). For ML, we conducted partitioned analyses in GARLI-PART v. 0.97 [40], and tested various partition schemes using Modeltest v. 3.7 [41] (see the electronic supplementary material). We used the best partition scheme to also search for the best ML tree and calculate bootstrap support in RAxML v. 7.0.4 [42]. In RAxML, we conducted a rapid bootstrap of 1000 replicates using the GTRCAT model [43,44] and the best likelihood tree using the GTRGAMMA model on the separate partitions, each with distinct models but joint branch-length optimization. We performed Bayesian inference using MrBayes v. 3.2 [45] using the same best partition scheme from the ML analysis and ran two Marko Chain Monte Carlo runs of four chains each for 20 million generations, sampling every 500th generation. We used default priors and unlinked all parameters across partitions except for branch-length calculations. Convergence of the two runs and stationarity were assessed using the AWTY tools [46]. A conservative burn-in of the first 4000 sampled generations was discarded.

We examined the robustness of our phylogenetic results by testing for topological instability and conflicts across the different loci. We used Mesquite v. 2.74 [47] to look at possible effects of missing data and rogue taxa, which cause instability or reduced resolution (see the electronic supplementary material). We examined genome-wide signal for the recovered relationships by comparing single-gene analyses with the combined analysis and looked for significant conflict in terms of relationships that were highly supported in the single-gene trees that were not found in the combined analysis. We also conducted a gene-jackknifing analysis in which we removed one gene at a time and analysed the remaining data in order to examine whether any relationships were driven by single genes (see the electronic supplementary material).

(b). Divergence times

We used the estimated dates in Barker et al. [35] for the split between Vireonidae and remaining corvoid birds (node 10 in Barker et al. [35]) as well as the split of a clade of shrike-like birds including Vanginae and Malaconotidae (node 11 in Barker et al. [35]). Most other recent studies [48–50] of corvoid birds have used the same calibration point to date divergences (the split of New Zealand from Gondwana at 82 million years corresponding to the basal divergence between Acanthisitta and all other passerines), therefore a range of potential calibrations was not available. Nevertheless, all of the studies using different analytical programmes have estimated roughly similar dates for those splitting events. We used r8s v. 1.71 [51] and both the non-parametric rate smoothing (NPRS) and penalized likelihood (PL) methods on the ML tree to estimate divergence times within vangas and their close relatives by setting the calibration point at the root of the tree (the split between vireos and other corvoids) to 37 million years ago [35]. Details are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

(c). Ancestral areas

We used Lagrange [52] to reconstruct ancestral areas using a likelihood method. We divided the globe into six relevant areas: Madagascar, Africa, tropical Asia, Eurasia (Palearctic), Australasia and Americas. Ranges of each terminal taxon were assigned based on the geographical extent of the respective genera. In Lagrange, we allowed ancestral areas to include any combination of areas except for two combinations of non-adjacent areas—Madagascar & Americas; Africa & Americas. We input the chronogram calculated by PL in r8s to run the Lagrange analysis. We set the program to estimate baseline rates of dispersal and local extinction. Given the small number of species in our phylogeny, in concert with low number of transitions between geographical regions, we did not attempt to account for regional differences in speciation and extinction rates [32,53] and consequent effects on the reconstruction of geographical character states.

(d). Lineage diversification rates

Under the ecological opportunity model, lineage diversification rates are expected to slow through time after initial colonization because of diversity-dependent feedback on speciation and/or extinction rates [32,54,55]. Under this ‘early burst’ model, lineage diversification is high immediately after colonization of a new region, but slows through time as niches get occupied and as ecological opportunities for speciation are diminished. Thus, the ecological opportunity model predicts a temporal deceleration in speciation within the Malagasy vanga radiation. We tested whether diversification rates varied through time following colonization of Madagascar using time-dependent diversification models described previously [55,56]. We fitted two time-constant and two time-varying models of diversification to the time-calibrated Malagasy vanga subclade.

One challenge in testing for temporal variation in diversification rates for vangas is that our sampling is both incomplete and phylogenetically non-random. To address this issue, we implemented a method for accommodating missing taxa in diversification analyses regardless of whether they are randomly or non-randomly sampled. To impute the position of ‘missing’ speciation times in our phylogeny, we used a variant of the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm that has been widely used to estimate missing data and latent variables in a variety of statistical applications [57]. We describe this method in detail in the electronic supplementary method. We also computed the gamma statistic [58], a measure of the distribution of speciation times in reconstructed phylogenetic trees. Gamma values significantly lower than those expected under constant-rate models of diversification imply a slowdown in speciation through time. See the electronic supplementary method for details.

(e). Foraging behaviour

The foraging behaviour of the vangas was described in depth by Schulenberg [28], Yamagishi & Nakamura [7] and Yamagishi & Eguchi [59]. We coded the foraging strategies employed by vangas and their close relatives as three main categories—gleaning, probing and sallying, as defined in Remsen & Robinson [60] (table 1). In cases where a taxon exhibits more than one mode, we coded this as a polymorphism. In cases where one behaviour is only rarely used, we examined coding as a polymorphism and as the dominant behaviour only. Both gave similar results in terms of reconstructing ancestral states. We used Mesquite to reconstruct the ancestral states of these traits using parsimony optimization. Because we had polymorphisms, we were unable to perform likelihood reconstructions.

Table 1.

Foraging behaviours of the Vangidae; the most frequently used techniques is listed first.

| Artamella | probing, gleaning |

| Calicalicus | gleaning |

| Cyanolanius | gleaning, sallying |

| Euryceros | sallying |

| Falculea | probing |

| Hypositta | gleaning |

| Leptopterus | gleaning, sallying |

| Mystacornis | gleaning, probing occasionally?a |

| Newtonia | gleaning |

| Oriolia | probing, gleaning |

| Pseudobias | sallying |

| Schetba | sallying |

| Tylas | gleaning, sallying |

| Vanga | sallying |

| Xenopirostris | probing, gleaning |

| Philentoma | gleaning; rarely sallying |

| Prionops | gleaning, sallying |

| Bias | sallying |

| Megabyas | sallying |

| Tephrodornis | gleaning, rarely sallying |

| Hemipus | gleaning, sallying |

aThere is evidence that Mystacornis uses probing behaviour to forage on the ground by sticking its bill into moss and dead material; this behaviour is somewhat different from that of the other vangas who probe, which tend to also manipulate the substrate by chiselling and stripping bark, etc.

3. Results

(a). Phylogenetic analysis

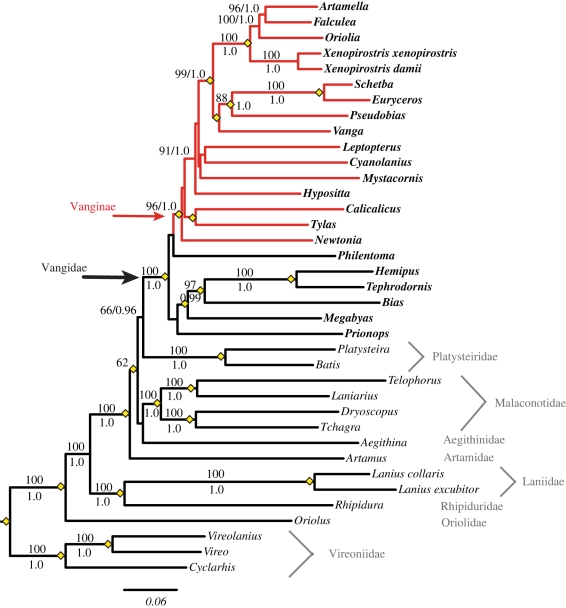

Our dataset had a total of 37 taxa and 11 118 aligned nucleotides from 13 genes, including four mitochondrial protein-coding genes (CYTB, ND2, ND3, COI), two rRNAs (12s, 16s), three nuclear exons (RAG1, RAG2, CMOS) and four nuclear introns (GAPDH, LDH, FIB5, MYO). All MP, ML and BI analyses of the combined dataset show that vangas are a monophyletic radiation endemic to Madagascar (figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2). This includes all the species in the traditional classification of the subfamily as well the newly proposed members such as Mystacornis, Newtonia, Tylas and Pseudobias. Nodal support for the monophyly of vangas is high in ML (96 Bootstrap (BS)) and BI (0.99 Posterior Probability (PP)), but not in MP (less than 50 BS).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships recovered using maximum likelihood (ML; GARLI). Vanginae are shown with red branches and the Vangidae are highlighted in bold. ML bootstrap support values are shown above nodes and Bayesian posterior probability values are below (or right) nodes on the ML tree. Yellow diamonds indicate where MP and ML topologies agree.

The closest relatives of vangas are a group of six Asian and African genera formerly placed in several different families at various times, including the Platysteiridae (Bias, Megabyas [6,7]), Malaconotidae (Prionops [5]), Prionopidae (Prionops, Philentoma, Tephrodornis [6]) and Campephagidae (Hemipus [5,6]), and incertae sedis (Philentoma, Tephrodornis [5]). In MP, these taxa fall into two groups with Tephrodornis, Hemipus, Bias, Megabyas in one clade as sister to the Malagasy vangas (Vanginae) and the clade of Philentoma + Prionops being sister to this larger clade. In ML and BI, Philentoma is consistently found as the sister species of Vanginae, although only with low support, and the remaining five are monophyletic, again with low support. The clade of vangas + the six relatives (hereby the Vangidae or vanga-shrikes) are found consistently in all analyses with high support (100 BS in ML, 1.0 PP in BI and 85 BS in MP). We found that the phylogenetic results were largely consistent across the different data partitions and analyses (see the electronic supplementary material).

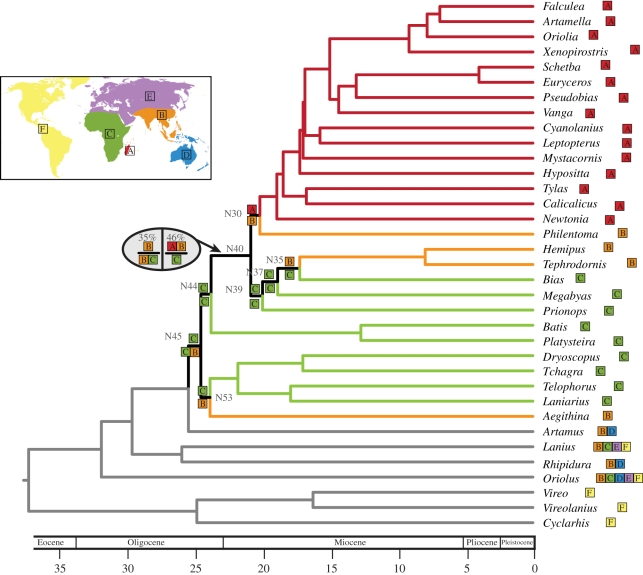

(b). Timing and biogeography

The divergence timing analysis shows that vangas reached Madagascar roughly 20 Ma (PL = 19.9; NPRS = 18.8, confidence intervals are shown in the electronic supplementary material, figure S3; figure 2). Diversification at the base of the clade including vangas and their shrike-like relatives (N45) happened relatively quickly, with this clade splitting from remaining corvoids at 24.2 Ma (PL; NPRS = 22.85) and subsequently colonizing Madagascar roughly four million years later. Accordingly, although we analysed a more finely sampled dataset of shrike-like corvoids, our dates are consistent with the results obtained for these nodes by Barker et al. [35] and Beresford et al. [48], the studies from which we derived our calibrations, and other recent studies that used somewhat different methods [61].

Figure 2.

Chronogram using penalized likelihood and ancestral area reconstruction using Lagrange. Nodes show the ancestral area(s) reconstruction with the highest likelihood of the descendant lineages on either side of split. Numbers at nodes prefixed with an ‘N’ refer to node numbers referenced in the text. For all nodes except N40, the reconstructions shown have about twice the relative probability (see the electronic supplementary material) as the next most likely. Coloured branches are used when all the descendant lineages are only found in a single area. Geographical areas are as follows: A (red), Madagascar; B (orange), Asia; C (green), Africa; D (blue), Australia; E (purple), Eurasia; F (yellow), Americas.

Results of the Lagrange ancestral area analysis are shown in figure 2. For all nodes, Lagrange reports multiple possible reconstructions within two likelihood units, however the reconstructions shown have about the twice the relative probability as the next most likely reconstruction (except for N40; see below). We predicted the ancestral areas of nodes within the clade of Asian-African-Malagasy shrike-like birds (node N45, figure 2). Lagrange predicts that the basal node of this lineage (N45) gave rise to descendants in Asia and Africa (Malaconotidae and Aegithinidae) and Africa (Platysteiridae, Vangidae). The ancestral distribution of Vangidae (N44) is Africa. In the first divergence within Vangidae (N40), there are two reconstructions with similar likelihoods and near relative probabilities—the first predicts the ancestral area at the top of the split to be Asia + Madagascar and the bottom of the split to be Africa (46% relative probability); the second predicts the ancestral area in the top to be Asia and the bottom to be Asia + Africa. The first reconstruction implies dispersal from Africa to Asia and Madagascar, although it is equivocal if this dispersal is from Africa to Asia and then Madagascar, or to Madagascar then Asia, or simultaneously to Asia and Madagascar. The second reconstruction also implies dispersal from Africa to Asia and then subsequently to Madagascar. From the African Vangidae (N39), there is a dispersal to Asia at N37 along the lineage leading to Hemipus and Tephrodornis.

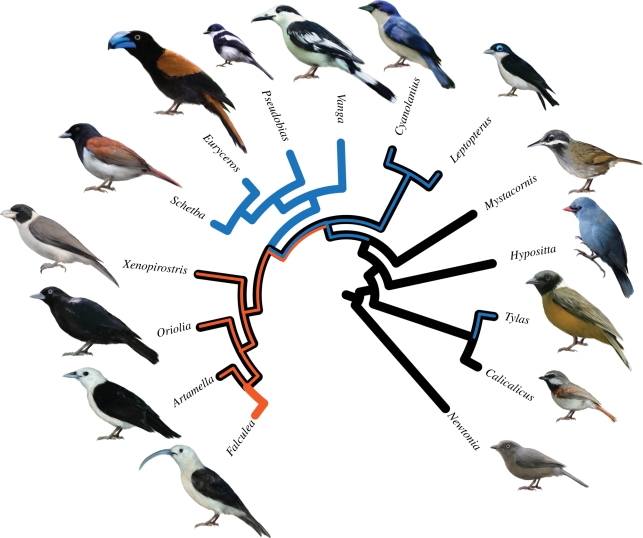

(c). Foraging behaviour

Optimizing and reconstructing ancestral states of foraging strategies show that the vangas first colonizing Madagascar were gleaners (figure 3). The basal divergences within Vanginae show these lineages to be mainly gleaners or generalist gleaners and salliers (figure 3), like their continental relatives (table 1). Probing vangas are united in one clade, as are vangas who are aerial or sallying specialists (figure 3). These two clades are sisters, a consistently well-supported relationship.

Figure 3.

The radiation of Vanginae and optimized foraging behaviour (table 1): black, gleaning; blue, sallying; red, probing. Illustrations of birds by Velizar Simeonovski.

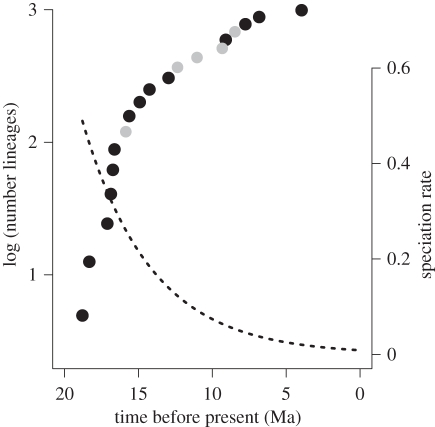

(d). Diversification rates

We used our implementation of the EM algorithm to estimate the positions of the five ‘missing’ speciation events in the Malagasy Vanginae (see §2). In each case, the ‘expectation’ step consisted of simulating subclades under the relevant diversification model, conditional on the full (sampled plus missing) diversity as well as the age of the subclade. These missing speciation times were then used jointly with the observed data to update parameters of the diversification model.

We found strong support for declining rates of speciation through time during the radiation of the Malagasy clade (table 2). The time-constant models provided a poor fit to the observed data (table 2) and the overall-best fit model specified an exponential decline in the rate of speciation through time (figure 4). Consistent with previous studies [56,62], extinction rates were estimated to be near zero under both time-constant and time-varying models of diversification.

Table 2.

Diversification-through-time patterns in Malagasy vangas. The λ model and the μ model give functional forms of speciation and extinction rates, respectively, through time under each fitted model; np is the number of parameters in each model and LogLik is log likelihood.

| model name | λ model | μ model | np | LogLik | AIC | ΔAIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pure birth | λ(t) = λ | μ(t) = 0 | 1 | −25.2 | 52.4 | 13.8 |

| birth–death | λ(t) = λ | μ(t) = μ | 2 | −25.2 | 54.4 | 15.8 |

| exponential, with extinction | λ(t) = λ0e−kt | μ(t) = μ0e−zt | 4 | −17.1 | 42.2 | 3.6 |

| exponential, no extinction | λ(t) = λ0e−kt | μ(t) = 0 | 2 | −17.3 | 38.6 | 0 |

Figure 4.

Tempo and mode of lineage diversification in Malagasy vangas. Black circles denote observed lineage-accumulation curve; grey circles are the locations of ‘missing’ speciation events estimated using the EM algorithm under the best-fit diversification model. ML estimate of speciation-through-time under exponential decline model is indicated by the dashed line.

Gamma statistics [58] computed for the Malagasy radiation provide further evidence for a slowing of speciation through time following the colonization of Madagascar. The observed gamma statistic (−3.32) is highly unlikely if speciation rates have been constant through time, under both random taxon sampling (p < 0.001) as well as ‘phylogenetically overdispersed’ taxon sampling (p = 0.017). This latter sampling model (see the electronic supplementary material) assumed a ‘worst case’ scenario for non-random taxon sampling, where only the most phylogenetically divergent subset of lineages was included in the analysis. These results are unlikely to be due to saturation of mtDNA: the observed gamma statistic was −3.52 for the PL-smoothed phylogeny constructed after excluding third codon positions from mtDNA protein coding genes. Finally, it is unlikely that this slowdown in diversification could have resulted from recent (post-Pleistocene) extinction of many vanga species or from the presence of unsampled (cryptic) species diversity. In the electronic supplementary material, figure S4, we demonstrate that at least 60 additional species of Malagasy vangas would have to be present (or to have recently gone extinct) to generate a gamma statistic of equal magnitude if speciation rates have truly been constant over time.

4. Discussion

(a). Vangidae

The origin of shrike-like corvoid birds in Madagascar has long fascinated ornithologists. Our study uncovers a novel group of species that are closely related to Malagasy vangas, which we place in the family Vangidae together with the vangas. This study is the first to show with strong support that the closest relatives of the Malagasy vangas (Vanginae) consist of species from both Africa and Asia.

The genera allied with the Malagasy vangas—Philentoma, Tephrodornis, Hemipus, Bias, Megabyas and Prionops—have all been notoriously hard to place within the Corvoids. They have been variously placed in several different oscine families, including Campephagidae, Malaconotidae, Platysteiridae and Prionopidae. This is the first study to bring all these aberrant taxa together in a phylogenetic analysis. We also find consistent, yet not strong, support for Philentoma to be the sister group to the Malagasy vangas, similar to Jonsson et al. [61].

(b). Monophyly of Vanginae

We find consistent support for the Vanginae being a monophyletic radiation endemic to Madagascar. Basal divergences in the Vanginae and Vangidae were rapid, leaving little signal to recover these deep branches. Data from 13 genes were needed to recover a strongly supported monophyletic Vanginae. As apparent from the gene-jackknifing and single-gene analyses, low support for the monophyly of this group with less data indicates poor signal at these basal, fast-paced divergence events.

Many of the relationships within Vanginae receive significant support, yet the placement of some species is weak, including many of the more ‘unstable’ taxa in our study as well as most of the taxa more recently identified to be part of the vanga radiation (i.e. Newtonia, Mystacornis and Hypositta). Eleven of the 15 genera of vangas are monotypic. Previously, three of these taxa, Leptopterus, Cyanolanius, Artamella, were categorized as congeners (in the genus Leptopterus). These taxa are not recovered as a monophyletic group and are instead distributed throughout the radiation. This is just one more example of how the extreme morphological differences between taxa have confused phylogenetic analyses and classifications. Our study samples only one set of congeneric species, Xenopirostris damii and Xenopirostris xenopirostris, which show a young divergence time. However in comparison, two considerably morphological divergent species, Euryceros and Schetba, show only a slightly greater genetic divergence (figure 1).

(c). Adaptive foraging strategies

A majority of Vangidae species glean arthropods from the surfaces of leaves or bark. This seems to be the primitive condition, with all of the early-diverging lineages of Vanginae exhibiting this behaviour and some of these lineages being generalists in terms of using gleaning, as well as an alternative behaviour, such as sallying. In a more derived clade of vangas, there is a split between species that probe versus species that specialize in sallying foraging techniques. All species in the Artamella-Falculea-Oriolia-Xenopirostris clade forage regularly if not primarily by probing with subsurface manoeuvres directed at bark or other woody substrates. This clade includes species with some of the most notable specialized bill morphologies among the vangas, including the deep, laterally compressed bills of the three species of Xenopirostris and the long, deeply curved (sickle-shaped) bill of Falculea. Species of vangas in this clade are important components of forest bird communities on Madagascar, with two or three species of probing vangas present at most sites (representing 5–14% of the passerine species diversity) [28]. Earlier authors [31] noted that Falculea filled a vacant woodpecker niche on Madagascar, but it was not recognized previously that Falculea is embedded within a small radiation of vangas with similar behaviours. The four taxa that use primarily sallying or aerial manoeuvres also are included in a single clade. Three of these taxa (Vanga, Schetba and Euryceros) sally to the ground or to foliage; perhaps the most specialized member of this clade, Pseudobias, sallies to air and to foliage. This study is the first to identify these taxa as a monophyletic group.

(d). Diversification of vangas and their relatives

The closest relatives of vangas are a group of shrike-like birds found primarily in the Old World tropics. Our biogeographic analysis shows that the Malagasy vanga radiation has connections to Asia as well as Africa. Most Malagasy fauna (birds, mammals, reptiles, etc.) were previously proposed to be derived from Africa, the closest mainland source. Our study tested different possibilities and provides evidence to substantiate the hypothesis of an Asian origin. Though the connection to Asia might be surprising, this is similar to patterns in other endemic radiations of Madagascar, both avian and non-avian [26,63–65].

Although our analysis is equivocal in terms of distinguishing the particular route of the vanga dispersal to Madagascar, all three scenarios of dispersal are intriguing: from Africa to Asia via Madagascar, to Madagascar via Asia, and simultaneously to Asia and Madagascar. The possibility of Philentoma arriving in Asia via Madagascar is intriguing because a lineage colonizing a mainland area from an island is considered a rare occurrence and has only recently been demonstrated [61,66].

Within the closest relatives of vangas, all genera have low species diversity, with one genus (Prionops) containing seven species, three genera (Philentoma, Hemipus and Tephrodornis) comprised of two species each, and two genera (Bias and Megabyas) being monotypic. All of these taxa are distributed in continental regions and even together do not equate the level of species diversity that radiated from the lineage that colonized Madagascar. This suggests these taxa did not diversify in these continental regions as successfully as vangas on Madagascar, perhaps owing to competition with other lineages, whereas the vangas on Madagascar probably encountered a depauperate avifauna and unoccupied niches upon colonization.

(e). Adaptive radiation in vangas

Increased diversification in the Vanginae correlates with the colonization of Madagascar. There is also remarkable congruence between feeding strategies and the phylogeny of this group. Given this, it is reasonable to assert that expanding and specializing feeding behaviours played a large role in the diversification and adaptive radiation of these groups within Madagascar, leading to the extreme morphological differentiation. Interestingly, the basal lineages of the Vangidae, both continental and Malagasy, all use a generalist or gleaning strategy and exhibit a great diversity in terms of plumage but do not show as much variation in bills compared with the more derived vanga groups.

Adaptive radiations, regardless of whether one views them as part of a continuum [67] or exceptional [1,2,4], have intriguing properties from which to study evolution. Our study shows that the incredible diversity of forms encompassed in the vangas of Madagascar arose as an in situ radiation and exhibits a pattern of diversification consistent with the ecological opportunity model. Upon colonization of Madagascar, the speciation rate of the early lineages was high and declined dramatically over time, presumably owing to the occupation and saturation of niches. We also show that foraging specializations in this group are due to common ancestry and that these adaptations led to further speciation. Both lines of evidence point towards speciation in vangas being driven by adaptation into unoccupied and novel ecological niches.

Acknowledgements

We thank Velizar Simeonovski for his extraordinary illustrations of birds. Fieldwork in Madagascar was authorized by the Direction des Eaux et Forests and the Commission Tripartite. For samples and logistics, we acknowledge the Field Museum of Natural History and, in particular, Steve Goodman. For helpful comments, we are grateful to John Bates, Cathy Bechtoldt, Nick Block, Josh Engel, Irby Lovette, Peter Makovicky, Rick Ree, V. V. Robin, Jason Weckstein, Dave Willard and Ben Winger. We also thank Associate Editor Trevor Price, Per Alström, and an anonymous reviewer for suggesting significant improvements to the paper. Laboratory work was conducted at the Pritzker Laboratory of Molecular Systematics at the Field Museum of Natural History and at the Laboratory of Analytical Biology at the Smithsonian Institution. This research was supported by grants from Sigma Xi, the University of Chicago (Neirman Fund), the American Museum of Natural History (Frank M. Chapman Fund), the Field Museum of Natural History (Reichelderfer Fund) and the National Science Foundation (DEB-0962078). Data generated in this study were deposited into GenBank (JQ239173-JQ239370).

References

- 1.Glor R. E. 2010. Phylogenetic insights on adaptive radiation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 41, 251–270 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173447 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173447) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schluter D. 2000. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamagishi S., Honda M., Eguchi K., Thorstrom R. 2001. Extreme endemic radiation of the Malagasy vangas (Aves: Passeriformes). J. Mol. Evol. 53, 39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Losos J. B., Mahler D. L. 2010. Adaptive radiation: the interaction of ecological opportunity, adaptation, and speciation. In Evolution since Darwin: the first 150 years (eds Bell M. A., Futuyma D. J., Eanes W. F., Levinton J. S.), pp. 381–420 Sunderland, MA: Sinauer [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickinson E. C. (ed.) 2003. The Howard and Moore complete checklist of the birds of the World, revised and enlarged. 3rd edn London, UK: Christopher Helm [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements J. F. 2007. The Clements checklist of birds of the world, 6th edn. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamagishi S., Nakamura M. 2009. Family Vangidae (Vangas). In Handbook of the birds of the world. Bush-Shrikes to Old World Sparrows, vol. 14 (eds del Hoyo J., Elliott A., Christie D.), pp. 142–171 Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansson U. S., Bowie R. C., Hackett S. J., Schulenberg T. S. 2008. The phylogenetic affinities of Crossley's babbler (Mystacornis crossleyi): adding a new niche to the vanga radiation of Madagascar. Biol. Lett. 4, 677–680 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0444 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0444) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulenberg T. S. 1995. Evolutionary history of the vangas (Vangidae) of Madagascar. PhD Committee on Evolutionary Biology. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manegold A. 2008. Composition and phylogenetic affinities of vangas (Vangidae, Oscines, Passeriformes) based on morphological characters. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 46, 267–277 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2008.00458.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2008.00458.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sibley C. G., Ahlquist J. A. 1990. Phylogeny and classification of birds. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plummer P. S., Belle E. R. 1995. Mesozoic tectono-stratigraphic evolution of the Seychelles microcontinent. Sediment. Geol. 96, 73–91 10.1016/0037-0738(94)00127-G (doi:10.1016/0037-0738(94)00127-G) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cracraft J. 2001. Avian evolution, Gondwana biogeography and the Cretaceous–Tertiary mass extinction event. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 459–469 10.1098/rspb.2000.1368 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1368) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noonan B. P., Chippindale P. T. 2006. Vicariant origin of Malagasy reptiles supports Late Cretaceous Antarctic land bridge. Am. Nat. 168, 730–741 10.1086/509052 (doi:10.1086/509052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoder A. D., Nowak M. D. 2006. Has vicariance or dispersal been the predominant biogeographic force in Madagascar? Only time will tell. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 405–431 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110239 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110239) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson G. G. 1940. Mammals and land bridges. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 30, 137–163 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali J. R., Huber M. 2010. Mammalian biodiversity on Madagascar controlled by ocean currents. Nature 463, 653–656 10.1038/nature08706 (doi:10.1038/nature08706) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller S., Schwarz M., Tierney S. 2005. Phylogenetics of the allodapine bee genus Braunsapis: historical biogeography and long-range dispersal over water. J. Biogeogr. 32, 2135–2144 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01354.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01354.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vences M., Vieites D. R., Glaw F., Brinkmann H., Kosuch J., Veith M., Meyer A. 2003. Multiple overseas dispersal in amphibians. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 2435–2442 10.1098/rspb.2003.2516 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2516) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoder A. D., Burns M. M., Zehr S., Delefosse T., Veron G., Goodman S. M., Flynn J. J. 2003. Single origin of Malagasy Carnivora from an African ancestor. Nature 421, 734–737 10.1038/nature01303 (doi:10.1038/nature01303) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCall R. A. 1997. Implications of recent geological investigations of the Mozambique Channel for the mammalian colonization of Madagascar. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 264, 663–665 10.1098/rspb.1997.0094 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0094) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wit M. J. 2003. Madagascar: heads it's a continent, tails it's an island. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 31, 213–248 10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141337 (doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141337) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keith S. 1980. Origins of the avifauna of the Malagasy region. In Proceedings of the 4th Pan African Ornithological Congress (ed. Johnson D. N.), pp. 99–108 Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Ornithological Society [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marks B. D., Willard D. E. 2005. Phylogenetic relationships of the Madagascar pygmy kingfisher (Ispidina madagascariensis). Auk 122, 1271–1280 10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[1271:PROTMP]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[1271:PROTMP]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warren B. H., Strasberg D., Bruggemann J., Prys-Jones R., Thébaud C. 2010. Why does the biota of the Madagascar region have such a strong Asiatic flavour? Cladistics 26, 526–538 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00300.x (doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00300.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren B. H., Bermingham E., Prys-Jones R. P., Thébaud C. 2005. Tracking island colonization history and phenotypic shifts in Indian Ocean bulbuls (Hypsipetes: Pycnonotidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 85, 271–287 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00492.x (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00492.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheldon F. H., Lohman D. J., Lim H. C., Zou F., Goodman S. M., Prawiradilaga D. M., Winker K., Braile T. M., Moyle R. G. 2009. Phylogeography of the magpie–robin species complex (Aves: Turdidae: Copsychus) reveals a Philippine species, an interesting isolating barrier and unusual dispersal patterns in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. J. Biogeogr. 36, 1070–1083 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02087.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02087.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulenberg T. S. 2003. Vangidae, vangas. In The natural history of Madagascar (eds Goodman S. M., Benstead J. P.), pp. 1138–1143 Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cibois A., Slikas B., Schulenberg T. S., Pasquet E. 2001. An endemic radiation of Malagasy songbirds is revealed by mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Evolution 55, 1198–1206 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00639.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00639.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cibois A., Normand D., Gregory S. M. S., Pasquet E. 2010. Bernieridae (Aves: Passeriformes): a family-group name for the Malagasy sylvioid radiation. Zootaxa 2554, 65–68 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreau R. E. 1966. The bird faunas of Africa and its islands. London, UK: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabosky D. L., Glor R. E. 2010. Equilibrium speciation dynamics in a model adaptive radiation of island lizards. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22 178–22 183 10.1073/pnas.1007606107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1007606107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoder J. B., et al. 2010. Ecological opportunity and the origin of adaptive radiations. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 1581–1596 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02029.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02029.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brock C. D., Harmon L. J., Alfaro M. E. 2011. Testing for temporal variation in diversification rates when sampling is incomplete and nonrandom. Syst. Biol. 60, 410–419 10.1093/sysbio/syr007 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barker F. K., Cibois A., Schikler P., Feinstein J., Cracraft J. 2004. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11 040–11 045 10.1073/pnas.0401892101 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuchs J., Bowie R. C., Fjeldsa J., Pasquet E. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of the African bush-shrikes and helmet-shrikes (Passeriformes: Malaconotidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 33, 428–439 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.06.014 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.06.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs J., Cruaud C., Couloux A., Pasquet E. 2007. Complex biogeographic history of the cuckoo-shrikes and allies (Passeriformes: Campephagidae) revealed by mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44, 138–153 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.014 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyle R., Cracraft J., Lakim M., Nais J., Sheldon F. 2006. Reconsideration of the phylogenetic relationships of the enigmatic Bornean Bristlehead (Pityriasis gymnocephala). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 39, 893–898 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.024 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swofford D. L. 2003. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4b10. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zwickl D. J. 2006. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. PhD dissertation. University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA [Google Scholar]

- 41.Posada D., Crandall K. A. 1998. Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14, 817–818 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. 2008. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web-servers. Syst. Biol. 57, 758–771 10.1080/10635150802429642 (doi:10.1080/10635150802429642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stamatakis A. 2006. Phylogenetic models of rate heterogeneity: a high performance computing perspective. In Proc. of the 20th International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), Rhodes Island, Greece, 25–29 April 2006. 10.1109/IPDPS.2006.1639535 (doi:10.1109/IPDPS.2006.1639535) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nylander J. A., Wilgenbusch J. C., Warren D. L., Swofford D. L. 2008. AWTY (are we there yet?): a system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 24, 581–583 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm388 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm388) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maddison W. P., Maddison D. R. 2010. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.73. See http://mesquiteproject.org

- 48.Beresford P., Barker F. K., Ryan P. G., Crowe T. M. 2005. African endemics span the tree of songbirds (Passeri): molecular systematics of several evolutionary ‘enigmas’. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 849–858 10.1098/rspb.2004.2997 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuchs J., Fjeldsa J., Bowie R. C., Voelker G., Pasquet E. 2006. The African warbler genus Hyliota as a lost lineage in the Oscine songbird tree: molecular support for an African origin of the Passerida. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 39, 186–197 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.020 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Njabo K. Y., Bowie R. C., Sorenson M. D. 2008. Phylogeny, biogeography and taxonomy of the African wattle-eyes (Aves: Passeriformes: Platysteiridae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 48, 136–149 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.01.013 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.01.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanderson M. J. 2003. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19, 301–302 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ree R. H., Smith S. A. 2008. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst. Biol. 57, 4–14 10.1080/10635150701883881 (doi:10.1080/10635150701883881) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldberg E. E., Lancaster L. T., Ree R. H. 2011. Phylogenetic inference of reciprocal effects between geographic range evolution and diversification. Syst. Biol. 60, 451–465 10.1093/sysbio/syr046 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillimore A. B., Price T. D. 2008. Density-dependent cladogenesis in birds. PLoS Biol. 6, e71. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060071 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rabosky D. L., Lovette I. J. 2008. Density-dependent diversification in North American wood warblers. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 2363–2371 10.1098/rspb.2008.0630 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0630) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rabosky D. L., Lovette I. J. 2008. Explosive evolutionary radiations: decreasing speciation or increasing extinction through time? Evolution 62, 1866–1875 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00409.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00409.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dempster A. P., Laird N., Rubin D. 1977. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Lond. B 39, 1–38 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pybus O. G., Harvey P. H. 2000. Testing macro–evolutionary models using incomplete molecular phylogenies. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 2267–2272 10.1098/rspb.2000.1278 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1278) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamagishi S., Eguchi K. 1996. Comparative foraging ecology of Madagascar vangids (Vangidae). Ibis 138, 283–290 10.1111/j.1474-919X.1996.tb04340.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1996.tb04340.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Remsen J. V., Jr, Robinson S. K. 1990. A classification scheme for foraging behavior of birds in terrestrial habitats. In Avian foraging: theory, methodology, and applications (eds Morrison M. L., Ralph C. J., Verner J., Jehl J. R., Jr). Studies in avian biology, vol. 13, pp. 144–160 See http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/cooper/sab_013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jonsson K. A., Fabre P. H., Ricklefs R. E., Fjeldsa J. 2011. Major global radiation of corvoid birds originated in the proto-Papuan archipelago. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2328–2333 10.1073/pnas.1018956108 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1018956108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morlon H., Potts M. D., Plotkin J. B. 2010. Inferring the dynamics of diversification: a coalescent approach. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000493. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000493 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Renner S. S. 2004. Multiple Miocene Melastomataceae dispersal between Madagascar, Africa and India. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 359, 1485–1494 10.1098/rstb.2004.1530 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1530) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sparks J. 2004. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the Malagasy and South Asian cichlids (Teleostei: Perciformes: Cichlidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 30, 599–614 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00225-2 (doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00225-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vences M., Freyhof J., Sonnenberg R., Kosuch J., Veith M. 2001. Reconciling fossils and molecules: Cenozoic divergence of cichlid fishes and the biogeography of Madagascar. J. Biogeogr. 28, 1091–1099 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00624.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00624.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Filardi C. E., Moyle R. G. 2005. Single origin of a pan-Pacific bird group and upstream colonization of Australasia. Nature 438, 216–219 10.1038/nature04057 (doi:10.1038/nature04057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Olson M. E., Arroyo-Santos A. 2009. Thinking in continua: beyond the ‘adaptive radiation’ metaphor. BioEssays 31, 1337–1346 10.1002/bies.200900102 (doi:10.1002/bies.200900102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]