Abstract

Lentiviral vectors are beginning to emerge as a viable choice for human gene therapy. Here, we describe a method that combines the convenience of a suspension cell line with a scalable, nonchemically based, and GMP-compliant transfection technique known as flow electroporation (EP). Flow EP parameters for serum-free adapted HEK293FT cells were optimized to limit toxicity and maximize titers. Using a third generation, HIV-based, lentiviral vector system pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis glycoprotein envelope, both small- and large-volume transfections produced titers over 1×108 infectious units/mL. Therefore, an excellent option for implementing large-scale, clinical lentiviral productions is flow EP of suspension cell lines.

Witting and colleagues describe a flow electroporation (flow EP) transfection method for efficient, scalable, nonchemically based and GMP-compliant production of lentiviral vectors. Both small- and large-scale flow EP transfections of serum-free adapted HEK293FT cells using a third-generation HIV-based lentiviral vector system produce titers over 1 × 108 infectious units/ml.

Introduction

Great potential in treating a variety of inherited and acquired diseases in humans exists for gene therapy. Successful, permanent gene correction typically requires the use of integrating viral vectors; the increasing popularity of modified retroviruses highlights this fact. For example, a recent clinical trial using Moloney murine leukemia virus to deliver adenosine deaminase (ADA) to CD34+ bone marrow cells reported long-term success in treating severe combined immunodeficiency caused by a lack of ADA (Aiuti et al., 2009). Future clinical trials, however, may trend toward the use of lentiviral vectors. These vectors possess the ability to integrate into the genome of both nondividing and dividing cells and have a reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis (Zufferey et al., 1998; Montini et al., 2009). A phase I clinical trial using lentiviruses to treat HIV (Levine et al., 2006) and a recent report showing transfusion independence in a β-thalassemia patient (Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010) illustrate these vectors' utility in clinical applications.

Expanded use of lentiviral vectors in early Phase I/II clinical trials necessitates efficient, large-scale production under current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) guidelines. To meet this demand, several investigators have created packaging cell lines (PCLs) to produce lentiviruses (Kafri et al., 1999; Klages et al., 2000; Farson et al., 2001; Pacchia et al., 2001; Sparacio et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2001; Kuate et al., 2002; Ikeda et al., 2003; Kumar et al., 2003; Ni et al., 2005; Cockrell et al., 2006; Broussau et al., 2008). The more successful PCLs utilized inducible expression systems in an attempt to circumvent cellular toxicity from HIV proteins and the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) envelope (Kafri et al., 1999; Klages et al., 2000; Pacchia et al., 2001; Sparacio et al., 2001; Cockrell et al., 2006; Ni et al., 2005; Broussau et al., 2008). Unfortunately, using PCLs in large productions is problematic due to technical constraints. For example, the generation of PCLs takes several months of clone isolation and characterization. Furthermore, due to vector component gene silencing, reduced titers are observed in PCLs over time (Ni et al., 2005).

As an alternative to PCLs, transient transfection methods allow rapid generation of clinical product and can be adapted quickly to new transgenes and pseudotypes. Such a strategy offers better flexibility in productions for early Phase I/II clinical trials. The most common transient transfection technique used in lentivirus production is calcium phosphate precipitation of DNA (Graham and van der Eb, 1973; Bajgelman et al., 2003; Karolewski et al., 2003; Sena-Esteves et al., 2004; Kutner et al., 2009). Disadvantages of the calcium phosphate method include reagent pH sensitivity (Karolewski et al., 2003) and effectiveness only in adherent cell lines. Other transient transfection methods using lipofection (Felgner et al., 1987) or polyethylenimine have been reported (Kuroda et al., 2009; Segura et al., 2010). However, their use may add significant cost to large-scale, clinical productions when cGMP-grade transfection reagents must be used.

PCLs and current transfection techniques have advantages, but they also have important disadvantages that may compromise or complicate the generation of lentiviral vector in large production batches (>50 L). Therefore, other methods should be examined. Electroporation (EP) is an efficient means to load foreign DNA inside the cell (Tsong, 1991; Rols, 2006). The mechanism is thought to involve the electrophoretic association of DNA with the plasma membrane with subsequent entry into the cell (Phez et al., 2005). This technology has been developed extensively over the past decade and several manufacturers offer electroporation units. However, most EP systems are designed to transfect relatively small volumes (typically in a cuvette). Flow EP addresses this limitation by continuously passing the desired volume of a cell and DNA suspension between two electrodes (Rols et al., 1992). The procedure can be effectively scaled up for large bioprocessing applications while maintaining regulatory compliance (Li et al., 2002, 2010). Flow EP also eliminates the need for chemical transfection reagents. These factors are highly relevant to a successful clinical lentiviral production.

In the current study, we report the suitability of using flow EP for large-scale productions of lentivirus. The productions consist of a “standard” third generation lentiviral vector expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) pseudotyped with the VSV-G envelope. We evaluated the lentiviral production efficiency of flow EP in different volumes benchmarked against cuvette or “static” EP. Next, our optimized flow EP method was compared to a standard calcium phosphate transfection in terms of titer, producer cell toxicity, and residual plasmid DNA. For each aspect, flow EP was equal to or outperformed calcium phosphate transfection. Therefore, this method is highly suited to lentiviral productions for early phase clinical gene therapy trials with potential for further scale-up.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HEK293 FT cells were obtained from Invitrogen. These cells stably express the SV40 T antigen from the pCMVSPORT6TAg.neo plasmid (the parental line was a fast-growing clone isolated from the HEK293 cell line; Graham et al., 1977). The HEK293 FT cells were adapted to serum-free conditions by MaxCyte and designated 293FT(s). Serum-free growth (SFG) media consisted of Freestyle 293 media supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), 5000 U/mL penicillin, 5000 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.1% anticlumping agent, and 50 μg/mL G418 (all from Invitrogen). Lentivirus production (LP) media consisted of SFG with no G418 supplement and the addition of 10 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma). 293FT(s) were cultured in T25 or T175 flasks on a platform shaker set at 60 rpm inside a cell culture incubator. HEK293T cells were obtained from the Cell Genesys and grown in D10 media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 1×Glutamax, 4.5 g/L glucose, 5000 U/mL penicillin, 5000 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum).

Plasmids

We used a third generation lentivirus with components split over four plasmids. A plasmid containing an HIV-based, self-inactivating lentiviral vector, pCSCGW (pCSC-SP-PW-GFP; Marr et al., 2004) expressing eGFP from a CMV promoter was used for transgene expression. The remaining three plasmids included the following: pMDL, containing the HIV GAG-POL gene; pMD2.g, containing VSV-G; and pRSV-REV, containing the HIV rev gene (Zufferey et al., 1998).

Growth of 293FT(s) cells in 10-L Cellbags

293FT(s) cells grown to maximum cell density (typically 2×106 to 3×106 cells/mL) in several T175 flasks were harvested by centrifugation and used to inoculate 2 L of SFG media in a 10L Cellbag (GE Healthcare) to a final concentration of 5×105 cells/mL. The 10-L Cellbag was mounted on a Wave bioreactor System 20/50 (GE Healthcare) and airflow was controlled with a CO2MIX20 (GE Healthcare). A CCA T/S blood gas analyzer with E-Glu cassettes (OPTI Medical) was used to monitor glucose, pH, pO2, and pCO2. The cells were further expanded to 5 L over 5 days with a complete media change-out occurring on day 3. Airflow was absent overnight on day 1 to prevent pH increase by excessive CO2 removal before cells were able to condition the 2 L of media. This was found not to be an issue when 5 L of media was used as on day 3. Media was added and removed from the Cellbag by using a peristaltic pump and tubing attached to the inoculation port.

Lentivirus production using EP

293FT(s) cells were harvested by centrifugation at 500×g for 5 min. After aspiration of the medium, cells were resuspended with 60% MaxCyte EP buffer (in sterile distilled water) (Li et al., 2002). The cells were again pelleted by centrifugation, the liquid aspirated, and resuspended in 60% EP Buffer. A viable cell count was obtained using a hemocytometer and trypan blue staining and the cell suspension adjusted to a concentration of 1×108 cells/mL. Plasmid molar ratios of 2:1:1:0.1 (CSCGW:MDL:REV:MDG) were used in the EP transfection cocktail. Cells were electroporated using a GMP-compliant, MXCT GT Flow Electroporation unit (MaxCyte) (Li et al., 2002, 2010) by using one of the following described methods.

For static EP, 1.5×107 cells and 5.9 μg of DNA (154.2 μL total volume) were added to an OC-400 EP cuvette (MaxCyte). After EP, cells were transferred to a T25 flask and incubated for 20 min in a 37°C cell culture incubator with 7.5 μg of DNase (Benzonase, EMD Biosciences or Pulmozyme, Genentech). LP media was added to the cells to a final volume of 4 mL. Viable cell count was obtained using a hemocytometer and trypan blue staining. Aliquots of virus-containing media were harvested 48 hr post-EP, filtered with a 0.45-μm syringe filter, and stored at −80°C.

For flow EP, 10–100 mL of cells at 1×108 cells/mL and 39.2 μg of DNA/mL of cells were added to a CL-2 EP assembly (MaxCyte). After EP, cells were transferred to multiple T175 flasks in volumes of 10 or 20 mL and incubated for 20 min in a 37°C cell culture incubator with 50 μg/mL of DNase (Benzonase or Pulmozyme). After incubation, cell suspensions were transferred to a 10-L Cellbag and cultured in a Wave bioreactor using the following settings: 25 rocks/min, 7.5° rocking angle, and 5% CO2 airflow of 0.3 L/min. T175 flasks were washed with LP media one to three times, pooled, and then added to the Cellbag to maximize cell recovery. Viable cell count was obtained using a hemocytometer and trypan blue staining. LP media was added to the Cellbag to obtain a final volume of 2.1 to 2.3 L. In some experiments after cells underwent flow EP they were transferred to T25 flasks for DNase treatment and viral production as described for static EP. Aliquots of virus-containing media were harvested 48 hr post-EP, filtered with a 0.45-μm syringe filter, and stored at −80°C.

Lentivirus production using calcium phosphate transfection.

HEK293T cells were seeded at 1.7×106 cells per T25 flasks or 5×106 cells per T75 flask. The following day, the cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method as previously described (Kahl et al., 2004). Cells were re-fed D10 media supplemented with 10 mM sodium butyrate (4 mL in T25 and 12 mL in T75 flasks) 16–18 hrs posttransfection. Lentivirus was harvested 48 hr posttransfection. Aliquots were filtered with a 0.45-μm syringe filter and stored at −80°C.

Infectious titer determination

HEK293T cells were plated in 12-well plates at a concentration of 1×105 cells/well. Serial dilutions of lentivirus-containing media with HEK293T growth media with 8 μg/mL polybrene was added to the cells 2 hr postplating in a final volume of 1 mL. Each dilution had at least two corresponding wells as replicates. Cells were harvested 3 days later for flow cytometric analysis using a FACSCalibur and Cellquest software (BD Biosciences). Infectious titers were determined using the dilution yielding 2%–20% GFP-positive cells with the following equation: (dilution×%GFP positive×100,000)/100. All titers were determined from aliquots that underwent one freeze–thaw cycle.

p24 assay

To determine p24 concentrations, serial dilutions of lentivirus-containing media were used with the HIV-1 p24ca Antigen Capture Assay Kit (AIDS Vaccine Program/SAIC-Frederick, Inc.). The manufacturer's protocol was followed.

Cell toxicity assay

Aliquots of lentiviral production supernatants were used in the Cell Death Detection ELISAplus kit (Roche Applied Science) according to manufacturer's instructions. This assay detects nucleosomes released into the media to give an overall estimate of cell necrosis. Absorbance values were converted to arbitrary units by multiplying by 1000.

Real-time PCR detection of plasmid DNA

DNA was extracted from a 0.5-mL aliquot of 48 hr lentivirus production supernatant using phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, pH 7.9). Precipitation of DNA was accomplished by adding 1 μL of 5 mg/mL linear acrylamide (Invitrogen), 33 μL of 3 M sodium acetate, and 735 μL of ethanol to 333 μL from the aqueous phase of the proceeding step. The mixtures were incubated overnight at −20°C. DNA precipitates were pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, resuspended in equal volumes of Tris buffer (pH 8.0), and concentrations determined. Real-time PCR was performed with 1 ng of the isolated DNA using primers to the ampicillin resistance gene as previously described (Sastry et al., 2004). Values are reported as nanograms of plasmid per milliliter of supernatant. This was obtained by multiplying the PCR results by the DNA dilution factor (variable) and then by three (due to precipitating 0.33 mL of supernatant).

Statistics

Data were analyzed by two tailed t test or one-way ANOVA where applicable, and p values under 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and Discussion

Optimization of EP conditions for lentivirus production

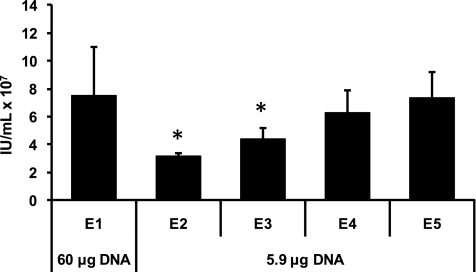

We have previously reported that static EP of lentiviral production plasmids generates high titers in HEK293T cells (Li et al., 2008). Considering the high cost of cGMP grade DNA used in clinical productions, achieving lower DNA concentrations requires further optimization of the EP conditions. Transfection efficiency with decreased DNA concentrations can be compensated for with increased electroporation energy (Kubiniec et al., 1990; Rols and Teissie, 1998). To apply this principle, a series of static, cuvette-based electroporations was performed with reduced DNA amounts but increasing levels of applied energy. Figure 1 shows a representative experiment where gradually increasing the total EP energy and using approximately one tenth of the DNA, we can obtain titers equivalent to the initially reported results (designated E1). Raising EP energy beyond the E5 value did not further increase titers (data not shown). Therefore, the E5 program settings were used in static EP for the remainder of this study.

FIG. 1.

Optimization of EP conditions at reduced DNA concentrations. Static EP with lentiviral plasmids was performed as described in the Methods section using either 60 μg or 5.9 μg of plasmid DNA. E values are preloaded computer-controlled protocols with increasing energy delivered to the cells (i.e., E1<E2<E3<E4<E5). Viral titers were determined by flow cytometric assay of 48-hr supernatants. Results are an average of three replicates. IU, infectious unit. *Signifies statistically significant difference with p<0.01 compared to E5 as determined by Student's t test.

Application of static EP settings to a flow EP program for scale-up

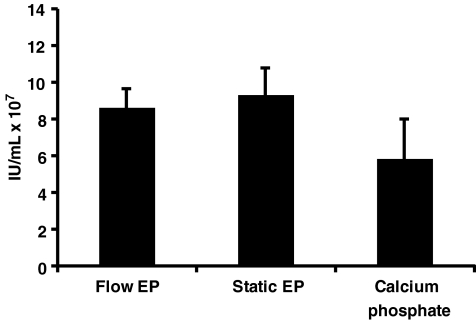

The MaxCyte GT flow EP system was designed to use static EP energy settings in a flow EP protocol without further optimization; this effectively allows for direct scale-up (Li et al., 2002). To confirm this ability in regards to lentivirus production in 293FT(s) cells, flow EP was executed with 10 or 50 mL of cell suspension. Static EP was done with an aliquot of the cells as a control. An equivalent amount of cells from each EP method were then transferred to T25 flasks for lentiviral production. Additionally, the calcium phosphate transfection method routinely used in our lab for lentivirus production in HEK293T cells (Kahl et al., 2004) was performed as a comparison. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, the average titers for flow EP, static EP, and the calcium phosphate method were not statistically significant. Our titers were also comparable to previously reported values for adherent HEK293T cells (Zufferey et al., 1998; Karolewski et al., 2003; Kutner et al., 2009). Interestingly, flow EP requires one third less DNA than the calcium phosphate method in a T25 flask lentivirus production (5.9 μg versus 9.2 μg of DNA). These results establish that flow EP can be successfully used for lentivirus production and titers achieved are at least equivalent to the calcium phosphate method.

FIG. 2.

Testing optimized static EP conditions in a flow EP protocol. Flow EP (two replicates with 10 mL and two replicates with 50 mL), static EP, or calcium phosphate transfection was performed as described in the Methods section. Equal counts of cells from each EP method were added to 4 mL of media for viral production. Viral titers were determined by flow cytometric assay of 48-hr supernatants. The group means were not statistically different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F2,8=3.15, p=0.098).

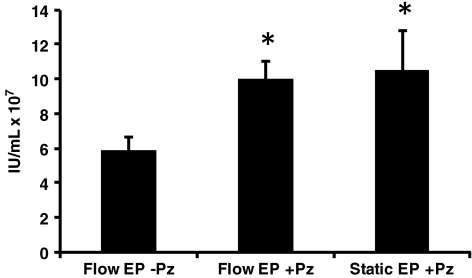

Pulmozyme DNase usage during recovery incubation increases titers

The addition of a bacterial sourced DNase (e.g., Benzonase, EMD Biosciences) to the cells immediately following EP improves viability which, consequently, improves lentivirus titers (Li et al., 2008). The mechanism of improved cell viability after EP is hypothesized to involve an increase in the plasma membrane sealing rate due to digestion of DNA on the plasma membrane (Li et al., 2008). DNase has previously been used in clinical lentiviral production protocols to eliminate plasmid contamination in the final product (Slepushkin et al., 2003; Levine et al., 2006). Pulmozyme, a human DNase approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in cystic fibrosis therapy, was examined as a potential alternative. 293FT(s) cells in a volume of 10 mL were transfected by flow EP. Aliquots of transfected cells were incubated with or without 50 μg/mL of Pulmozyme in T25 flasks. An equivalent number of cells transfected by static EP were similarly treated with 50 μg/mL of Pulmozyme as a control. As seen in Fig. 3, the addition of Pulmozyme increased the 48-hr titer almost twofold. Importantly, this step must be performed in cell culture vessels to allow for gas exchange. We observed that using capped tubes, even with a low volume of liquid, would kill most of the cells when incubated at 37°C for 20 min (data not shown). Pulmozyme was included in the flow EP protocol for the remainder of the study.

FIG. 3.

Increased titer with Pulmozyme treatment during EP recovery. Ten-milliliter flow or static EP was performed as described in the Methods section. Recovery incubation immediately following EP was performed with or without 50 μg/mL Pulmozyme in T25 flasks containing equivalent numbers of cells. Viral titers were determined by flow cytometric assay of 48-hr supernatants. Results are an average of two replicates. IU, infectious unit; Pz=Pulmozyme. *Signifies statistically significant difference with p<0.01 compared to Flow EP without Pulmozyme as determined by Student's t test.

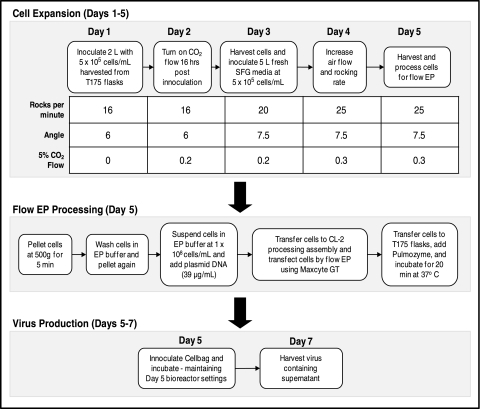

Lentivirus productions in a Wave bioreactor using flow EP transfected cells

In contrast to using multiple T-flasks, roller bottles, or cell factories, Wave bioreactors can be adapted to varying batch sizes in a single, closed system. We performed three independent, large-scale lentivirus productions in 10-L Cellbags (maximum liquid capacity of 5 L). The overall workflow for cell expansion and production is shown in Fig. 4. As detailed in Table 1, titers were consistent between productions and comparable to the small-scale titers (see Fig. 2). The specific productivity of each experiment was also consistent with approximately 40 infectious particles harvested per viable transfected cell (Table 1). Expressing the infectious titer data as a ratio with p24 assay data, the flow EP productions yielded values of greater than 1×105 IU/ng of p24 (Table 1). The ratios were slightly higher than previously reported values for calcium phosphate transfections (Mochizuki et al., 1998; Follenzi and Naldini, 2002). Elevated ratios indicate a higher percentage of infectious particles from total particles produced. Overall, flow EP is a viable method for large-scale lentivirus production.

FIG. 4.

Workflow of cell expansion and lentivirus production in Wave bioreactor using 10-L Cellbags. Cell expansion is initialized in 2 L of media and then scaled up to 5 L over a period of 5 days. On the fifth day, cells are harvested and subjected to flow EP. The transfected cells are added to fresh media and viral production occurred over days 6 and 7. Wave bioreactor settings on days 6 and 7 were maintained at day-5 values.

Table 1.

Titer Results of Large-Scale Lentivirus Productions in 10-L Cellbagsa

| Production no. | Volume (mL) | Total cells | 48-hr titer (IU/mL) | Cumulative titer (IU) | Productivity (IU/cell) | p24 (ng/mL) | IU/ng of p24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2300 | 6.0×109 | 9.8×107 | 2.2×1011 | 37 | 771±58 | 1.3×105 |

| 2 | 2300 | 4.8×109 | 8.8×107 | 2.0×1011 | 42 | 614±76 | 1.4×105 |

| 3 | 2100 | 7.4×109 | 1.3×108 | 2.7×1011 | 36 | 739±33 | 1.7×105 |

The total cell count is based on viable cells counted immediately following the addition of electroporated cells to the Cellbag. A reduction in the number of T175 flask washes (used in the post-EP Pulmozyme treatments) from three to one led to the slightly lower final volume in experiment 3. Viral titers and p24 assays were performed using aliquots of 48-hr posttransfection harvests.

Harvested supernatant from lentivirus productions may include contaminants in the forms of plasmid DNA from transfection. DNase treatment postproduction, as reported previously (Slepushkin et al., 2003; Transfiguracion et al., 2003; Sastry et al., 2004), is a highly effective way to eliminate residual plasmid. Since a DNase digestion step is performed post-EP, the elimination of residual plasmid was quantified by using a real-time PCR assay (Sastry et al., 2004). Plasmid DNA was detected in each production (Table 2). Except for production 2, plasmid contamination was slightly less than a T75 flask calcium phosphate transfection not treated with DNase. All values were within a range previously reported for unconcentrated lentiviral supernatants (Sastry et al., 2004). Consequently, the flow EP transfection method may still benefit from postharvest DNase treatment similar to calcium phosphate transfections in clinical productions.

Table 2.

Comparison of Lentivirus Harvest Contaminantsa

| Sample | Plasmid DNA (ng/mL) | Histone–DNA (arbitrary units) |

|---|---|---|

| Production 1 | 5±1 | 10±1* |

| Production 2 | 138±7 | 3±1* |

| Production 3 | 6±1 | 302±10* |

| CaPO4 transfection | 27±3 | 1040±194 |

Released cellular histone–DNA complexes and residual plasmid DNA assays were performed using aliquots of 48-hr posttransfection harvests. The CaPO4 transfection sample was not treated with DNase. Assay data are representative of at least two separate experiments.

Statistically significantly different at p<0.01 compared to CaPO4 transfection as determined by Student's t test.

To study contaminants specifically from producer cells, a commercial ELISA kit was employed to detect histone–DNA complexes released from necrotic cells. Data from a representative ELISA assay in Table 2 demonstrate that flow EP productions consistently resulted in significantly less necrotic marker. The differences cannot be accounted for by cell density alone. Calcium phosphate transfections average 2×106 to 3×106 cells/mL posttransfection; this count is comparable to the productions reported here with 293FT(s) cells (2.1×106 to 3.5×106 cells/mL). Taken as a whole, the data suggest the flow EP method yields similar, and possibly lower, producer cell contaminants when weighed against calcium phosphate transfection. Since serum-free media is utilized, further downstream purification can be carried out to effectively reduce contaminants (Slepushkin et al., 2003; Segura et al., 2007; Lesch et al., 2011).

The purpose was to develop a scalable GMP-compliant flow electroporation system for lentivirus production. The results demonstrated that flow electroporation development was successful overall (Table 1). However, the original strategy of performing 5-L productions was unfortunately limited to 2 L due to modest cell densities obtained during expansion. Independent of Cellbag size, we observed that 293FT(s) cells reach a maximum density of approximately 2×106 cells/mL (data not shown). Metabolic data provide clues to potential factors contributing to the modest cell densities. Metabolic readings at the time of lentivirus harvest were similar to those observed on Day 5 of cell expansion (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum). Although media oxygen saturation values (Supplementary Table S1) were in agreement with previous studies (Cote et al., 1998; Segura et al., 2007; Ansorge et al., 2009; Le Ru et al., 2010), the possibility cannot be ruled out that cell density was affected by oxygen saturation falling below a critical point in between measurements. As evidenced by increasingly lower pH in mature cultures (Supplementary Table S1), cell density could also be influenced by lactate accumulation from the metabolism of glucose. Taken together, the task of true scalability using flow EP of 293FT(s) cells for lentivirus production reduces to the further development of optimized culture conditions. Based on the current system, 10 L of 293FT(s) cells at maximum density would be required for a 5-L production. Two potential improvements for Wave bioreactor include using regulated, inline oxygen airflow to insure consistent oxygenation and/or a perfusion system to eliminate lactate. Using different bioreactors and HEK293-based suspension cell lines entirely (Cote et al., 1998; Segura et al., 2007; Le Ru et al., 2010), other studies have reported two- to threefold higher densities. As a result, it may be more straightforward to apply flow EP transfection to these other culture systems instead of optimizing 293FT(s) growth.

Another limitation of the flow EP protocol reported here is liquid handling. A benchtop centrifuge was used to pellet cells after removal from the cellbags by peristaltic pump. Even with 0.5-L bottles, this proved time consuming and led to some cell loss. More importantly, for a clinical production in which sterility is paramount, a more streamlined cell-harvesting method with limited use of transfer vessels is necessary. Such a method could utilize tangential flow filtration for cell harvesting and buffer exchanges. A further reduction in transfer vessels could be realized by using a single Pulmozyme treatment vessel instead of multiple T175 flasks (e.g., 2-L Cellbag). While the liquid handling in our study was not optimal, it does not diminish flow EP being an efficient transient transfection method for lentivirus production when processing large numbers of cells.

In summary, we have successfully demonstrated the ability to produce lentivirus on a significantly large scale using flow EP. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a flow EP method used to produce lentivirus in a bioreactor. As a transient transfection method, flow EP has the advantage of providing flexibility in early stage clinical trial productions while avoiding the caveats associated with PCLs. Additionally, flow EP lowers production costs by eliminating the need for cGMP-grade chemical transfection reagents. Although 293FT(s) cells are used in the present study, we stress the fact that flow EP can be successfully used with any HEK293-based suspension cell line in lentivirus productions. Future studies should explore further refinements and scale-up of this method.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R44HL088996-03 to Madhusudan Peshwa). Scott Witting was also supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P30 HL101337 to Kenneth Cornetta). The authors thank Dr. Philip Zoltick for the lentiviral transgene plasmid (pCSCGW) and Sarah Dolan and Priya Vallanda for excellent technical assistance.

Author Disclosure Statement

Lin-Hong Li, Cornell Allen, James Brady, Rama Shivakumar, and Madhusudan Peshwa are employed by MaxCyte.

References

- Aiuti A. Cattaneo F. Galimberti S., et al. Gene therapy for immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:447–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge S. Lanthier S. Transfiguracion J., et al. Development of a scalable process for high-yield lentiviral vector production by transient transfection of HEK293 suspension cultures. J. Gene Med. 2009;11:868–876. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajgelman M.C. Costanzi-Strauss E. Strauss B.E. Exploration of critical parameters for transient retrovirus production. J. Biotechnol. 2003;103:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(03)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussau S. Jabbour N. Lachapelle G., et al. Inducible packaging cells for large-scale production of lentiviral vectors in serum-free suspension culture. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:500–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M. Payen E. Negre O., et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human beta-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockrell A.S. Ma H. Fu K., et al. A trans-lentiviral packaging cell line for high-titer conditional self-inactivating HIV-1 vectors. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote J. Garnier A. Massie B. Kamen A. Serum-free production of recombinant proteins and adenoviral vectors by 293SF-3F6 cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998;59:567–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farson D. Witt R. McGuinness R., et al. A new-generation stable inducible packaging cell line for lentiviral vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001;12:981–997. doi: 10.1089/104303401750195935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgner P.L. Gadek T.R. Holm M., et al. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenzi A. Naldini L. Generation of HIV-1 derived lentiviral vectors. Methods Enzymol. 2002;346:454–465. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)46071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham F.L. van der Eb A.J. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology. 1973;54:536–539. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham F.L. Smiley J. Russell W.C. Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y. Takeuchi Y. Martin F., et al. Continuous high-titer HIV-1 vector production. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:569–572. doi: 10.1038/nbt815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafri T. van Praag H. Ouyang L., et al. A packaging cell line for lentivirus vectors. J. Virol. 1999;73:576–584. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.576-584.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl C.A. Marsh J. Fyffe J., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-derived lentivirus vectors pseudotyped with envelope glycoproteins derived from Ross River virus and Semliki Forest virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:1421–1430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1421-1430.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolewski B.A. Watson D.J. Parente M.K. Wolfe J.H. Comparison of transfection conditions for a lentivirus vector produced in large volumes. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003;14:1287–1296. doi: 10.1089/104303403322319372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klages N. Zufferey R. Trono D. A stable system for the high-titer production of multiply attenuated lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2000;2:170–176. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuate S. Wagner R. Uberla K. Development and characterization of a minimal inducible packaging cell line for simian immunodeficiency virus-based lentiviral vectors. J. Gene Med. 2002;4:347–355. doi: 10.1002/jgm.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiniec R.T. Liang H. Hui S.W. Effects of pulse length and pulse strength on transfection by electroporation. Biotechniques. 1990;8:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M. Bradow B.P. Zimmerberg J. Large-scale production of pseudotyped lentiviral vectors using baculovirus GP64. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003;14:67–77. doi: 10.1089/10430340360464723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda H. Kutner R.H. Bazan N.G. Reiser J. Simplified lentivirus vector production in protein-free media using polyethylenimine-mediated transfection. J. Virol. Methods. 2009;157:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner R.H. Zhang X.Y. Reiser J. Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:495–505. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru A. Jacob D. Transfiguracion J., et al. Scalable production of influenza virus in HEK-293 cells for efficient vaccine manufacturing. Vaccine. 2010;28:3661–3671. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch H.P. Laitinen A. Peixoto C., et al. Production and purification of lentiviral vectors generated in 293T suspension cells with baculoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2011;18:531–538. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B.L. Humeau L.M. Boyer J., et al. Gene transfer in humans using a conditionally replicating lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:17372–17377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. Liu L.N. Allen C., et al. DNase treatment following electrotransfection enhances cell viability and transgene expression. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:S315. [Google Scholar]

- Li L. Liu L.N. Feller S., et al. Expression of chimeric antigen receptors in natural killer cells with a regulatory-compliant non-viral method. Cancer Gene Ther. 2010;17:147–154. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.H. Shivakumar R. Feller S., et al. Highly efficient, large volume flow electroporation. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;1:341–350. doi: 10.1177/153303460200100504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr R.A. Guan H. Rockenstein E., et al. Neprilysin regulates amyloid Beta peptide levels. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004;22:5–11. doi: 10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki H. Schwartz J.P. Tanaka K., et al. High-titer human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vector systems for gene delivery into nondividing cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:8873–8883. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8873-8883.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E. Cesana D. Schmidt M., et al. The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:964–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI37630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y. Sun S. Oparaocha I., et al. Generation of a packaging cell line for prolonged large-scale production of high-titer HIV-1-based lentiviral vector. J. Gene Med. 2005;7:818–834. doi: 10.1002/jgm.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchia A.L. Adelson M.E. Kaul M., et al. An inducible packaging cell system for safe, efficient lentiviral vector production in the absence of HIV-1 accessory proteins. Virology. 2001;282:77–86. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phez E. Faurie C. Golzio M., et al. New insights in the visualization of membrane permeabilization and DNA/membrane interaction of cells submitted to electric pulses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1724:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rols M.P. Electropermeabilization, a physical method for the delivery of therapeutic molecules into cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rols M.P. Teissie J. Electropermeabilization of mammalian cells to macromolecules: control by pulse duration. Biophys. J. 1998;75:1415–1423. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rols M.P. Coulet D. Teissie J. Highly efficient transfection of mammalian cells by electric field pulses. Application to large volumes of cell culture by using a flow system. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;206:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry L. Xu Y. Cooper R., et al. Evaluation of plasmid DNA removal from lentiviral vectors by benzonase treatment. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:221–226. doi: 10.1089/104303404772680029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M.M. Garnier A. Durocher Y., et al. Production of lentiviral vectors by large-scale transient transfection of suspension cultures and affinity chromatography purification. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007;98:789–799. doi: 10.1002/bit.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M.M. Garnier A. Durocher Y., et al. New protocol for lentiviral vector mass production. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;614:39–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-533-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Esteves M. Tebbets J.C. Steffens S., et al. Optimized large-scale production of high titer lentivirus vector pseudotypes. J. Virol. Methods. 2004;122:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepushkin V. Chang N. Cohen R., et al. Large-scale purification of a lentiviral vector by size exclusion chromatography or Mustang Q ion exchange capsule. Bioproc. J. 2003 Sep-Oct;:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sparacio S. Pfeiffer T. Schaal H. Bosch V. Generation of a flexible cell line with regulatable, high-level expression of HIV Gag/Pol particles capable of packaging HIV-derived vectors. Mol. Ther. 2001;3:602–612. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transfiguracion J. Jaalouk D.E. Ghani K., et al. Size-exclusion chromatography purification of high-titer vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein-pseudotyped retrovectors for cell and gene therapy applications. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003;14:1139–1153. doi: 10.1089/104303403322167984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsong T.Y. Electroporation of cell membranes. Biophys. J. 1991;60:297–306. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K. Ma H. McCown T.J., et al. Generation of a stable cell line producing high-titer self-inactivating lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2001;3:97–104. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R. Dull T. Mandel R.J., et al. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J. Virol. 1998;72:9873–9880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9873-9880.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.