Abstract

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (Ca ex PA) is a carcinoma arising from a primary or recurrent benign pleomorphic adenoma. It often poses a diagnostic challenge to clinicians and pathologists. This study intends to review the literature and highlight the current clinical and molecular perspectives about this entity. The most common clinical presentation of CA ex PA is of a firm mass in the parotid gland. The proportion of adenoma and carcinoma components determines the macroscopic features of this neoplasm. The entity is difficult to diagnose pre-operatively. Pathologic assessment is the gold standard for making the diagnosis. Treatment for Ca ex PA often involves an ablative surgical procedure which may be followed by radiotherapy. Overall, patients with Ca ex PA have a poor prognosis. Accurate diagnosis and aggressive surgical management of patients presenting with Ca ex PA can increase their survival rates. Molecular studies have revealed that the development of Ca ex PA follows a multi-step model of carcinogenesis, with the progressive loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal arms 8q, then 12q and finally 17p. There are specific candidate genes in these regions that are associated with particular stages in the progression of Ca ex PA. In addition, many genes which regulate tumour suppression, cell cycle control, growth factors and cell–cell adhesion play a role in the development and progression of Ca ex PA. It is hopeful that these molecular data can give clues for the diagnosis and management of the disease.

Keywords: Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, Pathology, Carcinogenesis, Genes

Introduction

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (Ca ex PA) is defined as a carcinoma arising from a primary (de novo) or recurrent benign pleomorphic adenoma (PA) [1, 2]. Ca ex PA has been named as carcinoma ex mixed tumour, carcinoma ex adenoma, and carcinoma ex benign pleomorphic adenoma [1–3]. The current definition of Ca ex PA became widely accepted in the second half of the twentieth century. In the literature, Gnepp collated many studies from 1953 to 1991 and published a review on Ca ex PA in 1993 [1]. However, there is a lack of review of this topic in the recent literature. Also, the disease is uncommon and often poses a diagnostic challenge to clinicians and pathologists. In this study, we reviewed the recent literature and highlighted the current clinical, pathologic, and molecular perspectives regarding this entity.

Epidemiology

Gnepp summarizes approximately 60 series with Ca ex PA and noted that Ca ex PA constitutes approximately 3.6% of all salivary gland neoplasms, 6.2% of all mixed tumours, and 11.6% of all malignant salivary gland neoplasms [1]. Ca ex PA is uncommon, as it has a prevalence rate of 5.6 cases per 100,000 malignant neoplasms and a yearly incidence rate of 0.17 tumours per 1 million persons [1]. The cancer is found predominantly in the sixth to eighth decades of life and is slightly more common in females [1].

Geographical differences in the prevalence of Ca ex PA have been reported. Malata et al. [4], in 1997 noted that in the United Kingdom Ca ex PA forms about 25% of all primary parotid malignant neoplasms. On the other hand, a lower prevalence of Ca ex PA was reported in series from other countries. For instance, Byrne et al. [5] reported in 1988 that the cancer had a prevalence of 12% among primary parotid malignant neoplasms in the United States, whereas Zbären et al. [6] in 2008 showed that Ca ex PA comprises 14% of all primary parotid malignant neoplasms over a 20 year period in Switzerland.

Clinical Features

Ca ex PA is a carcinomatous transformation within a primary (de novo) or recurrent pleomorphic adenoma. Nouraei et al. [2] and Zbären et al. [6] observed that 25% of their 28 patients and 21% of their 24 patients, respectively, had a previously treated pleomorphic adenoma.

The most common clinical presentation of Ca ex PA is of a firm mass in the parotid gland. Nouraei et al. [2] reported the presence of a parotid mass in 96% of the 25 patients examined, whereas Olsen and Lewis noted a parotid mass in 86% of the 66 patients examined [2, 7].

Ca ex PA predominantly affects the major salivary glands with a majority of cases noted in the parotid and submandibular glands. The cancer has been known to manifest in the minor salivary glands in the oral cavity, particularly the hard and soft palate [8, 9]. On average, the cancers at these sites tend to be smaller than those arising from the major salivary glands. In addition to these sites, cases of Ca ex PA have been reported in the breast, lacrimal gland, trachea, and nasal cavity [10–13].

Ca ex PA can be asymptomatic as most of the cancers are not widely invasive and often have similar clinical presentations as PA [6, 7]. Pain usually results from local extension of the neoplasm into adjacent soft and hard tissues [6]. When Ca ex PA involves the facial nerve, the patient presents with facial nerve paresis or palsy. In the series by Olsen and Lewis examining 66 patients with Ca ex PA, facial nerve involvement was present in approximately one third of the cases (n = 21) [7]. Also, the clinical presentation may mimic a multiple facial nerve schwannoma [14]. In some instances, patients with Ca ex PA were reported to present with skin ulceration, tumour fungation, skin fixation, palpable lymphadenopathy and dysphagia [2, 7]. In addition, they may have swollen jaw (due to bone invasion), dental pain, and sudden loss of vitality [15]. The cancer has also been seen as a lacrimal sac mass, extending into the canaliculi and nasolacrimal duct, with or without chronic epiphora and recurrent dacryocystitis [11].

Patients frequently become aware of the cancer when they experience rapid enlargement of the mass, pain, or other clinical symptoms. On the other hand, rare patients with Ca ex PA may carry a slow growing mass for over 40 years before coming to clinical attention [7].

Increased preoperative duration of a PA increases the risk of malignant transformation into Ca ex PA. In Gnepp’s review, the cancer had a mean lead up time of 23.3 years, with half the patients aware of the swelling for about 2–3 years [1]. Although the time from the onset of symptoms until diagnosis varied dramatically from 1 month to 52 years, more recent literature showed a mean lead up time of 9 years, with half the patients being aware of a painless mass for less than 1 year [7, 16]. Since the presenting symptoms are quite similar to those presenting with a benign PA, it is important that clinicians maintain a high level of clinical suspicion, which can be challenging considering the rarity of this cancer.

Pathology

Macroscopic

The proportions of adenoma and carcinoma components determine the macroscopic features of this neoplasm. When the PA component is dominant, the tumour looks greyish-blue, and transparent to yellowish-white. This appearance may be related to hyalinization and calcification in the stroma. On the other hand, when the malignant components are dominant, the tumour is widely infiltrative, resulting in necrosis and haemorrhage, and can easily be recognized as a malignant tumour. The size of the tumours varies from 1 to 25 cm [1, 7, 17].

Microscopic

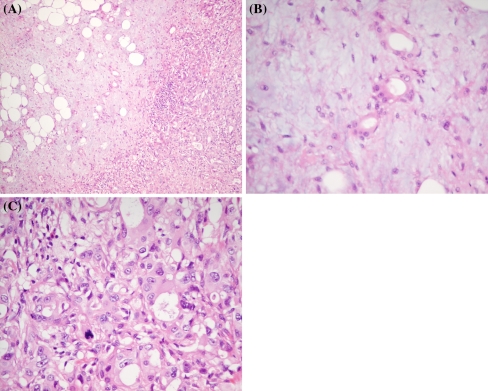

Ca ex PA, by definition, is composed of a mixture of PA and carcinoma on microscopic examination (Fig. 1). Lewis et al. [17], in an analysis of 73 cases of Ca ex PA noted that the carcinomatous component made up more than 50% of the cancer in 84% of cases. Zbären et al. [6], in an analysis of 19 Ca ex PA cases, reported that the carcinomatous components made up less than 33% of the tumour in 21% of the neoplasms, between 33 and 66% in 37% of the neoplasms and greater than 66% in 42% of the neoplasms. In certain cases, the carcinoma grows to occupy the entire neoplasm leaving no trace of the PA component. In this instance, the detection of the PA component relies on previous biopsy, clinicopathologic correlation or additional sectioning of the specimen. Alternatively, the cancer can be predominantly the PA component with sparse, scattered foci of malignant transformation characterized by nuclear pleomorphism, frequent/atypical mitotic figures, haemorrhage, and necrosis. These cases often leave pathologists with a diagnostic challenge and may lead to a misdiagnosis thereby adversely affecting the treatment protocol.

Fig. 1.

a Ca ex PA demonstrating the co-existence of PA (left) and carcinoma (right) components (H&E, original magnification ×10). b Higher magnification of the PA area in a composed of glands with myoepithelial cells radiating out in a myxoid stroma (H&E, original magnification ×40). c Higher magnification of the carcinoma area in a composed of a poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma with scanty glandular formation, marked nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitosis (H&E, original magnification ×40)

Based on the presence and extent of invasion of the carcinomatous component outside the fibrous capsule, Ca ex PA can be subdivided into non-invasive Ca ex PA, minimally invasive Ca ex PA, and invasive Ca ex PA [18, 19]. Olsen et al. [7] noted that the extent of invasion beyond the fibrous capsule ranged from 2 to 100 mm with a mean of 24 mm.

The concept of non-invasive Ca ex PA was first introduced in 1977 by LiVolsi and Perzin [20] in a study of 47 cases of Ca ex PA. It is also known in the literature as intra-capsular CA ex PA and carcinoma in situ [21, 22]. The carcinoma component in a non-invasive Ca ex PA is confined within the well-defined fibrous capsule of the PA. Although non-invasive Ca ex PA marks the beginning of the malignant transformation, it tends to exhibit the benign behaviour of PA [20, 23]. Zbären et al. [6] noted that at the time of histological analysis, 26% of the Ca ex PAs examined fall under this category.

When the malignant component of Ca ex PA undergoes <1.5 mm penetration into extracapsular tissue, it is classified as minimally invasive Ca ex PA [18]. Histologically, it is very similar to intra-capsular Ca ex PA with varying proportions of mixed tumour areas, intra-ductal carcinoma areas and carcinoma areas [6, 21]. Zbären et al. [6] noted that in the study of 24 Ca ex PA, 37% of the Ca ex PAs were classified as minimally invasive.

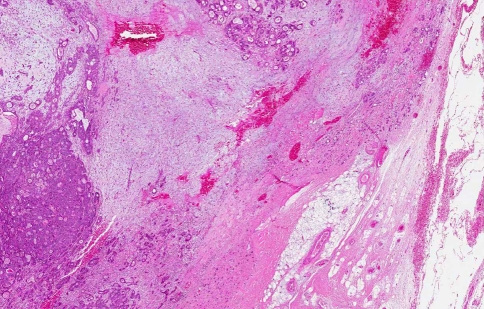

Invasive Ca ex PA is defined as greater than 1.5 mm invasion by the malignant component from the tumour capsule into adjacent tissue [18] (Fig. 2). The PA areas are composed of nodules of hyalinized tissue with sparse, scattered ductal structures as the carcinoma areas increase in proportion. Although the invasive carcinoma areas are very similar to those described in intra-capsular Ca ex PA carcinoma areas, there is an increased tendency for malignant cells to decrease in size and migrate away from the origin [19].

Fig. 2.

Ca ex PA with invasion outside the capsule. The carcinoma forms tiny glands and nests infiltrating through the capsule into the adjacent adipose tissue (H&E, original magnification ×2)

Ca ex PA can also be divided into those with only epithelial (luminal) malignancy and those with myoepithelial (non-luminal) malignancy. According to the study by Demasi et al. [21] of 16 cases of Ca ex PA, cancers with only epithelial (luminal) malignancy formed 75% of all cases. These Ca ex PAs were found across the entire spectrum of invasion, from intra-capsular Ca ex PA to frankly invasive Ca ex PA. The study suggested that Ca ex PA with only epithelial differentiation were limited to the major salivary glands [21]. Ca ex PA with myoepithelial differentiation can be further subdivided into those that exhibit both epithelial and myoepithelial malignancy and those with exclusive myoepithelial malignancy. Those with exclusive myoepithelial malignancy are quite rare. Altemani et al. [19] observed that the malignant transformation of myoepithelial cells results in the absence of ductal structures. Ca ex PAs with myoepithelial differentiation were usually frankly invasive and were found in both the major and minor salivary glands.

The malignant component of Ca ex PA is most often adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified. Sometimes, the component may be adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, or salivary duct carcinoma. The other less common histological subtypes include acinic cell carcinoma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma [6, 16, 17, 24]. The malignant component may also be a mixture of subtypes. For instance, Nakamori et al. [25] reported a case of Ca ex PA with the presence of squamous cell carcinoma and salivary duct carcinoma. It is worth noting that in metastases of Ca ex PA, only the carcinomatous component was present.

Diagnosis

Pathological assessment is the gold standard for making the diagnosis. Prior to surgical excision, diagnostic modules can include fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), sonography, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Studies comparing the preoperative diagnostic accuracy of sonography, CT and MRI in diagnosing Ca ex PA are few. MRI is considered the superior diagnostic tool over CT as it is most sensitive in detecting malignancy and allows better delineation of tissue planes. Kato et al. [26] suggested the use of diffusion-weighted MRI to enhance the differentiation of cancer areas in Ca ex PA.

FNAC is commonly used pre-operatively to diagnosis Ca ex PA. The sensitivity, however, is low largely related to sampling error. Klijanienko et al. [27] reported the largest series of findings of FNAC in Ca ex PA in 1999 and reviewed the literature to date. They noted that 13 of 26 (50%) patients were diagnosed by FNAC. In their review of the literature (including their cases), 54% (36 of 67) of Ca ex PA cases were diagnosed pre-operatively by FNAC. They also showed that high-grade carcinoma was more likely to be diagnosed than low-grade carcinoma. However, a more recent series showed a much lower sensitivity for FNAC. In 2008, Zbären et al. [6] reported that 44% (7 of 16) Ca ex PA cases showed malignant cells at FNAC whereas Nouraei et al. [2] noted that 29% (4 of 14) of the cancers were positive for malignancy by FNAC. Overall, none of these pre-operative diagnostic measures are of high accuracy when used alone. Hence, a combination of these diagnostic tools, such as using MRI scan and FNAC, should be utilised to make a preoperative diagnosis [28].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a slow growing parotid mass that has recently exhibited a growth spurt should raise the suspicion of a Ca ex PA. A Ca ex PA can be mistaken for a benign PA. It can also be misdiagnosed as other benign and malignant salivary gland tumours [29]. A high grade salivary gland adenocarcinoma that is difficult to classify should include Ca ex PA in its differential. Metastatic mixed tumour is less common than Ca ex PA [30] and is differentiated from Ca ex PA by having no carcinomatous component.

Treatment

Treatment for Ca ex PA often involves an ablative surgical procedure which may or may not be followed by reconstructive surgery. Since Ca ex PA predominantly affects the parotid gland, the ablative surgery often involves parotidectomy. Superficial parotidectomy is used for intracapsular or minimally invasive Ca ex PA localized to the superficial lobe of the parotid gland. Total or radical parotidectomy is indicated for frankly invasive Ca ex PA. Total parotidectomy involves the resection of both the deep and superficial lobes of the parotid and every attempt is made to preserve the facial nerve. If the facial nerve is involved by the cancer, a radical parotidectomy involving resection en bloc of the facial nerve along with the deep and superficial lobes of the parotid is performed. A concomitant neck dissection may be needed if cervical lymph nodes show evidence of metastases. Neck dissection can be functional, modified, or radical. The literature is limited on which of these procedures is most beneficial to the patient [2, 7].

The surgical procedure to remove the neoplasm may be followed by an immediate reconstructive surgery. Facial reanimation surgery that involves immediate sural nerve grafting may be performed. However, this is not undertaken in the case of longstanding preoperative facial nerve palsy. A soft tissue reconstruction like radial forearm free flap, a sternomastoid flap or a cervical rotation flap is performed in some instances.

The surgical approach varies according to the sites of the Ca ex PA. For example, Baredes et al. [11] recommends the use of lateral rhinotomy and medial maxillectomy for Ca ex PAs of the lacrimal gland that seems to have a higher success rate than a resection through dacryocystectomy. This was followed by an en bloc resection of the medial maxilla along with the nasolacrimal apparatus. Surgical management of a tracheal Ca ex PA involves segmental tracheal resection with suprahyoid release [12]. Post-operative radiotherapy is used for high grade disease, in cases of questionable resection adequacy, and for lymph node and peri-neural invasion [16]. Patients can also be offered the option of combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, there is limited literature on the effectiveness of chemotherapy in the management of Ca ex PA [2, 16].

Prognosis

The prognosis of Ca ex PA depends on pathological staging parameters like the level of invasion, lymph node involvement, and local or distant metastasis [1, 18]. Also, patients with non-invasive or minimally invasive Ca ex PA have better prognoses than patients with invasive Ca ex PA [18]. Furthermore, tumour size and grade are also noted to be significant prognostic indicator in invasive Ca ex PAs [18]. Patients with high grade carcinomatous components have poor prognosis when compared to patients with low grade carcinomatous components [17]. Clinically, the prognosis of the cancer also depends on the completeness of the tumour resection [18]. In addition, accurate diagnosis and aggressive surgical and radiological management of patients presenting with Ca ex PA may increase the survival rates of patients with Ca ex PA [18].

Overall, the survival rate for Ca ex PA was worse than for most salivary gland malignancies.

The survival rates of the patients with Ca ex PA vary. In the older series, Gnepp presented a 5-year survival range of 25–65% [1]. Olsen et al. [7] noted a 5 year disease-specific survival rate of 37% in 73 patients with the cancer and Nouraei et al. [2] reported 44% survival rates in 28 patients with the cancer. On the other hand, Zbären et al. [6] noted a higher survival rate of 75% in their series of 24 patients and Luers et al. [16] reported a survival rate of 60% in 22 patients with the cancer [6]. The higher survival rate noted by Zbären et al. [6] may due to the higher proportion of intra-capsular Ca ex PA in their study, which behaves like a benign PA and, hence, has a better prognosis [16].

Loco-regional recurrence is considered to be a major prognostic factor for patients with Ca ex PA. Olsen et al. [7] reported local recurrence in 23% of patients and regional recurrence in 18% of patients with Ca ex PA. The prognosis after detection of progression or recurrence is poor, with a median survival of less than 1 year. Olsen et al. [7] noted that all disease specific deaths occurred within 6 years after the initial operation and Nouraei et al. [2] reported absence of disease specific deaths after 5 years of surgery.

Molecular Pathology

Recent molecular analysis of CA ex PA has given new data on its carcinogenesis. These include the data from chromosomal analyses and more specific data on the individual genes involved in CA ex PA.

Chromosomal Changes

The development of CA ex PA follows the multi-step model of carcinogenesis demonstrating progressive loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at chromosomal arms 8q, then 12q, and finally 17p. El-Naggar et al. [31] analysed DNA from PAs and CA ex PAs and concluded that both PAs and the benign components of CA ex PA showed most LOH on chromosomal arm 8q, with progressively rarer losses on 12q and 17p. However, the carcinomatous components specifically exhibited a similar or slightly higher LOH at 8q and a significantly higher LOH on chromosomal arms 12q and 17p [31]. Hence, LOH on chromosomal arm 8q is indicative of early events in a PA, while loss on chromosomal arm 12q identifies the subset of adenomas with potential for malignant transformation. Alterations at 17p are present in the late event of carcinogenesis, i.e. Ca ex PA [31].

There are specific candidate genes in these regions that are associated with particular stages in the progression of Ca ex PA. Early alterations of chromosomal arm 8q in a PA often involve PLAG1 (8q12.1), an adenoma associated gene, and MYC (8q22.1–q24.1), a known oncogene, resulting in their overexpression [32, 33]. However, the malignant transformation of a PA to Ca ex PA can be attributed to the 12q genes, HMGIC, HMGA2 and MDM2. Röijer et al. [32] noted a translocation involving a 12q breakpoint 5′ of HMGIC followed by the translocation of HGMGIC and MDM2 resulting in deletion/amplification. Alterations of HMGA2 include amplification disruption of the 5′ or entire coding sequence, and gene fusion, particularly with WIF1. MDM2 is frequently co-amplified with HMGA2.

Tumour Suppressors and Cell Cycle Control

The p53 gene is a tumour suppressor, implicated in the development and progression of many cancers. It is located at 17p13. Fowler et al. [34] showed that 17p loss was common in Ca ex PA, indicating that p53 is thereby commonly lost in the pathogenesis of Ca ex PA. Mutation of p53 is also implicated in the malignant transformation of Ca ex PA. Point mutation of p53 in Ca ex PA was first reported by Righi et al. [35]. The authors also reported positive p53 protein expression and mutation in 4 cases of Ca ex PA. Ihrler et al. [36] reported the expression of p53 protein (positive in 15 of 19 cases) in intraductal Ca ex PA with high grade cellular atypia. This study also found p53 mutations in 37% (7 of 19 cases) of cases of Ca ex PA. In addition, Ihrler et al. [36] noted a high incidence of p53 protein accumulation in cases with no p53 mutation. Similar results concerning p53 overexpression and mutation were also noted previously by Nordkvist et al. [37]. These studies suggest a role for p53 in the malignant transformation of Ca ex PA. A recent study by Gedlicka et al. [38], however, did not find any p53 mutations in the 11 cases of Ca ex PA studied. Thus, p53-independent progression of PA to Ca ex PA is possible.

The cyclin D1 and p16 genes are involved in cell cycle regulation. Oncogenic effects of cyclin D1 are similar to those of inactivation of p16, which is a known tumour suppressor. Deregulation of these genes has importance in the development and progression of human cancers. Patel et al. [39] found increased immunohistochemical staining for both cyclin D1 and p16 proteins in the malignant epithelial component of Ca ex PA (n = 14) compared to normal epithelial and stromal components.

p21 is an another cell cycle regulatory protein whose inhibitory effects on cell division can lead to cancerous changes in normal cells when disrupted by mutation or other factors. Tarakji et al. [40] reported p21 protein expression in 33% (9 of 27) of cases of Ca ex PA, increasing from only 6.9% in PA. Their results indicated that the expression of p21 may increase as Ca ex PA progresses, implicating it or its controlling genes in disease progression.

COX-2

Another gene commonly dysregulated in cancer is COX-2. COX-2 is expressed in response to tumour necrosis factor, epidermal growth factor and other genes, and catalyses the formation of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid [41, 42]. COX-2 is associated with increased angiogenesis and cellular proliferation and its over-expression has been found in colorectal, head and neck, and other cancers [42]. Katori et al. [43] found that Ca ex PA expressed COX-2 specifically in the high grade carcinomatous component. The authors also found that expression of COX-2 was significantly lower in PA than Ca ex PA, indicating that increased COX-2 expression may be an important early stage event in the pathogenesis of the disease [43].

Growth Factors and Receptors

Fibroblast growth factors (FGF) are small polypeptide growth factors that have a role in anti-apoptosis, tumour growth, differentiation, and angiogenesis [44]. Martinez et al. [45] reported FGF-2 protein over-expression in the myoepithelial cells of Ca ex PA. They also noted that the myoepithelial cells over-expressing FGF-2 might interact in a paracrine manner with the FGF-2 receptors on the epithelial cells nearby to induce a malignant transformation [45]. In addition, the results implied that this increased FGF-2 expression was induced by the malignant cells, since cultured benign cells increased expression of FGF-2 when exposed to serum from malignant cells. This suggests that a paracrine feedback loop is in operation and may be involved in the transition of in situ to invasive carcinoma. While FGFR-1 is expressed in PAs, FGFR-2 is not present in PAs but is strongly expressed in Ca ex PA [46]. This would indicate that it is through FGFR-2 that the effects of FGF-2 in Ca ex PA are mediated.

Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ-1) acts as a tumour suppressor gene in the early stages of malignancy. In cancer of advanced stages, TGFβ-1 plays a role in the survival, progression, and metastasis of the entity by encouraging epithelial mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, and evasion of immune surveillance. While TGFβ-1 expression was observed in 10/10 cases examined by Furuse et al. [46], it was absent in the epithelial and myoepithelial cells of PA. Transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα) is involved in the maturation and differentiation of keratinocytes. Katori et al. [41] observed elevated levels of TGFα in the 39 cases of Ca ex PA examined, with significant overexpression in the high grade carcinomatous components and low staining levels in the low grade carcinomatous components.

HGF-A (scatter factor) and c-Met (a proto-oncogene) play a role in angiogenesis and tumour progression and were strongly expressed in 10/10 cases of Ca ex PA [46]. Similarly IGFR-1, observed in 10/10 cases of Ca ex PA by Furuse et al. [46], is often detected in many cancers.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is important in invasive progression of Ca ex PA from intra-capsular to frank invasion, as the phosphorylation of EGFR triggers multiple biological processes essential for motility and matrix invasion. Katori et al. [41] noted that EGFR is over expressed in high grade Ca ex PAs and shows low staining levels in low grade Ca ex PA similar to TGFα.

C-erbB-2 (HER2) is a cell membrane surface-bound receptor tyrosine kinase and is normally involved in the signal transduction pathways leading to cell growth and differentiation. C-erbB-2 protein expression in parotid adenocarcinoma (Ca ex PA) was first reported by Sugawara et al. [47]. Another study reported 15% (2 of 13) of Ca ex PA showing c-erbB-2 protein over-expression and DNA amplification [48]. C-erbB-2 protein expression in Ca ex PA was also studied in a larger series (19 cases) by Rosa et al. [49]. Immunohistochemical staining of C-erbB-2 protein was found to be higher (21%) in cell membranes of high grade Ca ex PA [49]. Rosa et al. [49] also found negative C-erbB-2 protein expression in low grade Ca ex PA, as did Di Palma et al. [22] in their study of 11 Ca ex PA cases. These findings indicate that C-erbB-2 may play a role in tumour progression and malignant transformation of Ca ex PA. Anti-C-erbB-2 therapy (Herceptin) has been successfully used to control a case of advanced Ca ex PA. This would lend additional weight to research identifying high expression in high grade forms of the disease [50].

Cell Adhesion Molecules

E-cadherin, neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM), and beta-catenin play a crucial role in cell to cell adhesion and maintaining epithelial morphology. Positive E-cadherin expression was reported in a case of Ca ex PA with relatively less reactivity compared to benign tumours [51]. Also, Economopoulou et al. [52] reported focal loss of E-cadherin protein expression in 3 cases of Ca ex PA. Saleh et al. [53] showed that Ca ex PA cells express N-CAM at much lower levels than maternal PA. Genelhu et al. [54] found increased immunohistochemical staining of beta-catenin in Ca ex PA (7 cases), of which well differentiated Ca ex PA (4 of 7) showed protein staining in the cytoplasm and poorly and undifferentiated Ca ex PA showed beta-catenin expression in either cytoplasm or in the nucleus. Genelhu et al. [54] also found decreased cell membrane beta-catenin protein expression in high grade Ca ex PA. In addition, Araujo et al. [55] examined E-cadherin and beta-catenin expression in Ca ex PA, with similar findings to those above. Interestingly, they showed that the presence of type I collagen was associated with the above mentioned alterations in expression of E-cadherin and beta-actin [55]. This implies that E-cadherin, N-CAM, and beta-catenin in concert with extracellular matrix proteins may play a role in histological differentiation and malignant transformation of PA to Ca ex PA.

Conclusion

CA ex PA is an uncommon entity with significant clinical and pathological relevance. It is important to be aware of the disease as it is difficult to be diagnosed both clinically and pathologically. In recent years, many molecular studies have revealed that the development of Ca ex PA follows a multi-step model of carcinogenesis. There are also specific candidate genes that are associated with the development and progression of Ca ex PA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Alexander C L Chan from Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong for his contribution to the figures.

Footnotes

Joyce Antony and Vinod Gopalan were contribute equally to the work.

References

- 1.Gnepp DR. Malignant mixed tumours of the salivary glands: a review. Pathol Annu. 1993;28:279–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nouraei SA, Hope KL, Kelly CG, et al. Carcinoma ex benign pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1206–1213. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000181654.68120.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuroishikawa M, Kiyosawa M, Akashi T, et al. Case of lacrimal gland carcinoma ex adenoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004;48:181–182. doi: 10.1007/s10384-003-0025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malata CM, Camilleri IG, McLean NR, et al. Malignant tumours of the parotid gland: a 12 year review. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:600–608. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1226(97)90505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne MN, Spector JG. Parotid masses: evaluation, analysis, and current management. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:99–105. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198801000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zbären P, Zbären S, Caversaccio MD, Stauffer E. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: diagnostic difficulty and outcome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:601–605. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen KD, Lewis JE. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a clinicopathological review. Head Neck. 2001;23:705–712. doi: 10.1002/hed.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damm DD, Fantasia JE. Large palatal mass. Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. Gen Dent. 2001;49:574–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshihara T, Tanaka M, Itoh M, et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the soft palate. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:240–243. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100129809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes MM, Lesack D, Girardet C, et al. Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the breast. Report of three cases suggesting a relationship to metaplastic carcinoma of matrix-producing type. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:142–149. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baredes S, Ludwin DB, Troublefield YL, et al. Adenocarcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:940–942. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200306000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding CS, Yap WM, Teo CH, et al. Tracheal carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a rare tumour with potential problems in diagnosis. Histopathology. 2007;51:868–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho KJ, el-Naggar AK, Mahanupab P, et al. Carcnioma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the nasal cavity: a report of two cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:677–679. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100131019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park KC, Choi HJ, Kwon JK. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma mimicking multiple facial nerve schwannoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewan K, Owens J, Silvester K. Maintaining a high level of suspicion for recurrent malignant disease: report of a case with periapical involvement. Int Endod J. 2007;40:900–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luers JC, Wittekindt C, Streppel M, et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Study and implications for diagnostics and therapy. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:132–136. doi: 10.1080/02841860802183604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Sebo TJ. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: pathological analysis of 73 cases. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:596–604. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.25000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World health organisation classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altemani A, Martins MT, Freitas L, et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA): immunoprofile of the cells involved in carcinomatous progression. Histopathology. 2005;46:635–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LiVolsi VA, Perzin KH. Malignant mixed tumours: a clinicopathological study. Cancer. 1977;39:2209–2230. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197705)39:5<2209::AID-CNCR2820390540>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demasi AP, Furuse C, Soares AB, et al. Peroxiredoxin I, platelet-derived growth factor A, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha are overexpressed in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: association with malignant transformation. Human Pathol. 2009;40:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Palma S, Skalova A, Vanieek T, et al. Non-invasive (intracapsular) carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: recognition of focal carcinoma by HER-2/neu and MIB1 immunohistochemistry. Histopathology. 2005;46:144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandwein M, Huvos AG, Dardick I, et al. Noninvasive and minimally invasive carcinoma ex mixed tumor. A clinicopathologic and ploidy study of 12 patients with major salivary tumors of low (or no) malignant potential. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol Endod. 1996;81:655–664. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negahban S, Daneshbod Y, Shishegar M. Clear cell carcinoma arising from pleomorphic adenoma of a minor salivary gland: report of a case with fine needle aspiration, histologic and immunohistochemical findings. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:687–690. doi: 10.1159/000326043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamori K, Ohuchi T, Hasegawa T, et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the buccal region is composed of salivary duct carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma components. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:1116–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato H, Kanematsu M, Mizuta K, et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: radiologic-pathologic correlation with MR imaging including diffusion-weighted imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:865–867. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klijanienko J, El-Naggar AK, Vielh P. Fine-needle sampling findings in 26 carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenomas: diagnostic pitfalls and clinical considerations. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:163–166. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199909)21:3<163::AID-DC3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raine C, Saliba K, Chippindale AJ, et al. Radiological imaging in primary parotid malignancy. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:637–643. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Palma S, Lambros MB, Savage K, et al. Oncocytic change in pleomorphic adenoma: molecular evidence in support of an origin in neoplastic cells. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:492–499. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.031369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Fernandez J, Mateos-Micas M, Martinez-Tello FJ, et al. Metastatic benign pleomorphic adenoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Naggar AK, Callender D, Coombes MM, et al. Molecular genetic alterations in carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma: a putative progression model? Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:162–168. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(200002)27:2<162::AID-GCC7>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Röijer E, Nordkvist A, Ström AK, et al. Translocation, deletion/amplification, and expression of HMGIC and MDM2 in a carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:433–440. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64862-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martins C, Fonseca I, Roque L, et al. PLAG1 gene alterations in salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma: a combined study using chromosome banding, in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fowler MH, Fowler J, Ducatman B, et al. Malignant mixed tumors of the salivary gland: a study of loss of heterozygosity in tumor suppressor genes. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:350–355. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Righi PD, Li YQ, Deutsch M, McDonald JS, et al. The role of the p53 gene in the malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:2253–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ihrler S, Weiler C, Hirschmann A, Sendelhofert A, et al. Intraductal carcinoma is the precursor of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma and is often associated with dysfunctional p53. Histopathology. 2007;51:362–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nordkvist A, Röijer E, Bang G, Gustafsson H, et al. Expression and mutation patterns of p53 in benign and malignant salivary gland tumors. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:477–483. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gedlicka C, Item CB, Wögerbauer M, et al. Transformation of pleomorphic adenoma to carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland is independent of p53 mutations. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:127–130. doi: 10.1002/jso.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel RS, Rose B, Bawdon H, Hong A, et al. Cyclin D1 and p16 expression in pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Histopathology. 2007;51:691–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarakji B, Nassani MZ, Sloan P. Immunohistochemical expression of estrogens and progesterone receptors in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma-undifferentiated and adenocarcinoma types. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:432–436. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katori H, Nozawa A, Tsukuda M. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor, transforming growth factor-alpha and Ki-67 in relationship to malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:1207–1213. doi: 10.1080/00016480701230894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawata R, Hyo S, Araki M, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katori H, Nozawa A, Tsukuda M. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and Ki-67 are associated with malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powers CJ, McLeskey SW, Wellstein A. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors and signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7:165–197. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez EF, Demasi AP, Miguita L, et al. FGF-2 is overexpressed in myoepithelial cells of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma in situ structures. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:155–160. doi: 10.3892/or_00000840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuse C, Miguita L, Rosa AC, et al. Study of growth factors and receptors in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sugawara K, Mori S, Morita M. Expression of c-erbB-2 protein detected in adenocarcinoma arising from parotid pleomorphic adenoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1990;17:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(12)80193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Müller S, Vigneswaran N, Gansler T, et al. c-erbB-2 oncoprotein expression and amplification in pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: relationship to prognosis. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:628–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosa JC, Fonseca I, Félix A, et al. Immunohistochemical study of c-erbB-2 expression in carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. Histopathology. 1996;28:247–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharon E, Kelly RJ, Szabo E. Sustained response of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma treated with trastuzumab and capecitabine. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prabhu S, Kaveri H, Rekha K. Benign and malignant salivary gland tumors: comparison of immunohistochemical expression of e-cadherin. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Economopoulou P, Hanby A, Odell EW. Expression of E-cadherin, cellular differentiation and polarity in epithelial salivary neoplasms. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:515–518. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(00)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saleh ER, França CM, Marques MM. Neural adhesion molecule (N-CAM) in pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:562–567. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Genelhu MC, Gobbi H, Arantes DC, et al. Immunolocalization of beta-catenin in pleomorphic adenomas and carcinomas ex-pleomorphic adenomas of salivary glands. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:273–278. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000213123.04215.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.deAraújo VC, Furuse C, Cury PR et al. Desmoplasia in different degrees of invasion of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1:112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]