Abstract

Smoking is responsible for over 400,000 premature deaths in the United States every year, making it the leading cause of preventable death. In addition, smoking-related illness leads to billions of dollars in healthcare expenditures and lost productivity annually. The public is increasingly aware that successfully abstaining from smoking at any age can add years to one’s life and reduce many of the harmful effects of smoking. Although the majority of smokers desire to quit, only a small fraction of attempts to quit are actually successful. The symptoms associated with nicotine withdrawal are a primary deterrent to cessation and they need to be quelled to avoid early relapse. This review will focus on the neuroadaptations caused by chronic nicotine exposure and discuss how those changes lead to a withdrawal syndrome upon smoking cessation. Besides examining how nicotine usurps the endogenous reward system, we will discuss how the habenula is part of a circuit that plays a critical role in the aversive effects of high nicotine doses and nicotine withdrawal. We will also provide an updated summary of the role of various nicotinic receptor subtypes in the mechanisms of withdrawal. This growing knowledge provides mechanistic insights into current and future smoking cessation therapies.

Keywords: Reward, negative motivation, dopamine, withdrawal, VTA, nucleus accumbens, habenula, addiction, drug abuse, nicotinic receptors, nicotinic knockout mice

1 Introduction

In the United States, about 21% of adults currently smoke cigarettes [1]. Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death, responsible for 443,000 premature deaths every year. The economic impact is staggering, with a cost to the health care system of about $96 billion and $97 billion in lost productivity [2]. Smoking decreases one’s life expectancy mostly due to tobacco-related vascular, neoplastic, and respiratory disease [3]. Specifically, lung cancer is highly attributable to smoking and is the leading cause of cancer death among men and women [4]. To never smoke is obviously the best strategy to avoid the deleterious consequences of smoking, but for those who have become addicted, quitting brings significant benefits. A smoker who quits at 35 years of age will live about 8 years longer than a continuing smoker [5], and will have a similar life expectancy as a never smoker [3]. Even quitting in old age can add years to one’s life [5]. However, in a given year, only 3% of smokers are actually successful in their cessation attempts, even though 70% of smokers express desire to quit [6].

Nicotine, the major addictive component of tobacco, binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR). nAChRs are ligand gated ion channels activated by the endogenous neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh). Neuronal type nAChRs are composed of differing combinations of α and β subunits, with nine genes encoding α subunits (α2–10) and three encoding β subunits (β2–4)[7–9]. α7 homomers and α4β2 heteromers represent the two major nAChR subtypes found throughout the brain but other nAChR subunit combinations are expressed in selected brain areas [9–13].

Genetic, developmental, and environmental factors determine whether someone will become addicted to the nicotine contained in tobacco [6, 14, 15] and will start to smoke compulsively, despite well known health consequences [16, 17]. The addiction process involves the activation of various brain circuits, including the dopaminergic (DAergic) reward system and the circuits that underlie motivation, decision making, and habit formation [18]. Many neurotransmitters and neuropeptides are involved in the process, as nAChRs are strategically positioned to modulate the release of virtually every major neurotransmitter [8, 19, 20]. The neuroadaptations arising from chronic nicotine exposure cause widespread alterations in brain neurotransmission that promote and sustain the use of tobacco [21–24]. Smoking cessation disrupts the equilibrium maintained in the presence of nicotine and leads to the manifestations of withdrawal. The symptoms associated with the nicotine abstinence syndrome contribute to the maintenance of the smoking habit and are a potent deterrent for those who are trying to quit [25–27]. The following sections summarize our current understanding of the mechanisms underlying the behavioral manifestations of nicotine withdrawal and discuss existing and potential strategies for smoking cessation.

2 The Dopaminergic system, goal-directed behavior, and nicotine’s effects

2.1 Role of the Dopaminergic system

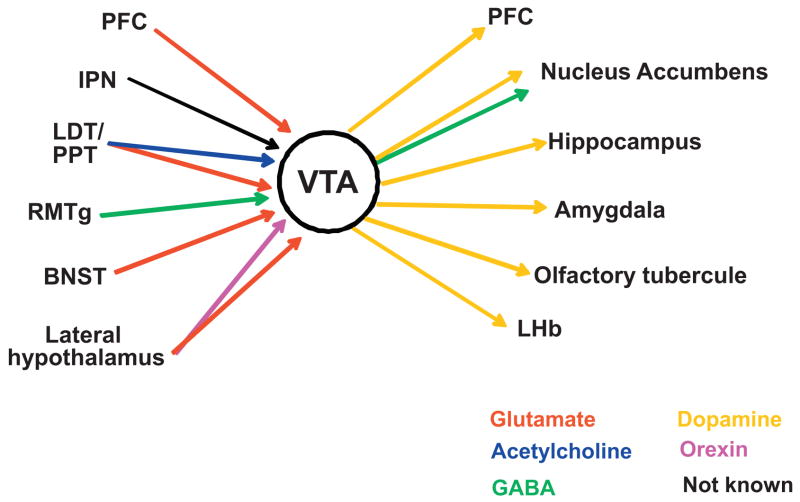

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra provide the major source of dopamine (DA) in the brain. The role of the DAergic system (in particular the mesocorticolimbic pathway) in drug addiction derives from DA’s ability to modulate many of the limbic and cortical sites involved in goal-directed behavior (Fig. 1) [18, 28–31]. Presentation of natural reinforcers, such as food and sex, causes DA neurons to switch from low-frequency tonic activity at rest to phasic bursting. The DA released encodes reward prediction errors and incentive salience and provides a learning signal for the optimization of goal-directed behavior [31, 32]. Addictive drugs, including nicotine, hijack the mechanisms of experience-dependent adaptive behavior and lead to abnormally high DA levels [33]. Repeated exposure to the drug results in synaptic adaptations that produce behavioral changes. Although changes in DA levels are the main feature of addictive drugs, it should be kept in mind that other neurotransmitters and neuropeptides participate in nicotine reward, including glutamate, cannabinoids, and opioids [34–37].

Fig. 1.

Major VTA afferent and efferent projections. VTA DA neurons send projections to NAcc, PFC, the hippocampus, the amygdala and the olfactory tubercule [256]. Through those projections, the DAergic system influences reward-related behavior by affecting reinforcement (NAcc), learning and declarative memory (hippocampus), emotional memory (amygdala), habit formation (ventral and dorsal striatum), and executive functions and working memory (PFC and orbitofrontal cortex). The activity of the VTA is in turn regulated by inputs from the PFC, the laterodorsal and pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei (LDT/PPT), the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMT), the lateral hypothalamus, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) [257–260]. DA neurons also receive inhibitory inputs from intra-VTA GABAergic neurons, NAcc, and ventral pallidum [261,262]. Neurotrasmitters are color coded as indicated.

2.2 Cholinergic influences over midbrain DA neurons and ventral striatum

The cholinergic system exerts a profound effect on DAergic activity as ACh released in the VTA promotes the switch between tonic and phasic activity in DAergic neurons that signals reward and salience [38, 39]. Cholinergic inputs to the midbrain DA center originate from the pedunculopontine tegmentum (PPT) and the laterodorsal tegmentum (LDT) in which cholinergic neurons are interspersed with GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons [40–42]. The PPT/LDT are also the source of the excitatory glutamatergic inputs to the DA neurons projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) [40]. Various nAChR subtypes are expressed on midbrain DA, GABA, and glutamatergic neurons, and nAChRs are also expressed on afferent projections including those from cortex, PPT/LDT, and the NAcc [43–45]. nAChRs are also present on DAergic axon terminals [13, 46] and GABA interneurons in the NAcc [47]. In the NAcc, cholinergic innervation arises from striatal interneurons [48–50]. Each of these neuronal subpopulations expresses nAChRs of differing subunit compositions and with differing cellular localizations [8, 9, 51]. By binding to those nAChRs, nicotine can alter DAergic activity by directly activating DA neurons in the VTA and by modulating the release probability of both inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters from presynaptic terminals in VTA and NAcc. These actions result in enhanced neuronal firing beyond that normally driven by environmental cues and contribute to the addiction process [52]. Pharmacological experiments, the analysis of nAChR null mice, and lentivirus-based re-expression studies are providing constant refinement to our understanding of the effects of nicotine on the circuits underlying goal-directed behavior (Table 1).

Table 1. nAChR influences on neurotransmitter release.

Neurotransmitters released in response to nicotine, the brain areas where this release is known to occur, and nAChR subtypes known to facilitate this action.

| Neurotransmitter Released | Brain Region | nAChRs involved | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | VTA NAcc PFC |

α4β2*, α4*,α6*, α6β2* α4β2*; α7 |

[13, 264–266] [12, 13, 267, 268] [269] |

| Glutamate | VTA NAcc PFC Amygdala IPN |

α7 β2* ? α4β2*; α7 α4β2*; α7 α7 |

[270, 271] [272] [269, 273] [272, 274–277] [278] |

| GABA | VTA NAcc Amygdala |

α6β2* α4β2* α3β4*; α7 |

[279, 280] [47, 281] [276, 282] |

| Acetylcholine | MHb IPN |

α3β4*, α3β3β4 | [223] |

| Norepinephrine | Hippocampus Cortex |

α3β4*, β4* (rat); α6β2β3* (mouse) α3β2*, α6* |

[283, 284] [285] |

VTA, ventral tegmental area; NAcc, nucleus accumbens; PFC, prefrontal cortex; IPN, interpeduncular nucleus; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; MHb, medial habenula. The asterisk denotes the potential presence of other nAChR subunits.

2.3 The habenula as a source of anti-reward

Although it was originally postulated that the DA released from the VTA only mediates the hedonic or pleasurable effects of natural reinforcers, it is now clear that changes in DAergic activity can also signal punishment, aversion, or lack of expected reward [53–58]. Reward omission induces phasic inhibition of VTA neurons [56, 57] and aversive stimuli excite ventral [58] and inhibit dorsal [55] VTA neurons. Moreover, aversive stimuli increase the firing of NAcc neurons [59]. The fact that inhibition of VTA neurons can signal the motivational value of unexpected and aversive stimuli suggests the existence of neuronal circuits that interact, and partially overlap, to maximize reward and minimize aversive effects. Nicotine follows an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve [18, 60], and smokers titrate their nicotine intake to experience the rewarding while avoiding the aversive effects produced by high nicotine doses [61–64]. Our understanding of the circuits and molecular mechanisms governing the processing of aversive stimuli, including the effects of high nicotine doses, is still limited. However, the habenular complex, which receives inputs from the VTA, is emerging as an important component in the process.

The habenula is an epithalamic nucleus involved in the mechanisms of fear, anxiety, depression, and stress [18, 30, 65, 66]. It is divided into the medial nucleus (MHb) and the two divisions of the lateral nucleus (LHb). The LHb receives inputs mainly from the basal ganglia and sends outputs to DAergic neurons and serotonergic neurons, while the MHb receives inputs mainly from the limbic system and sends outputs to the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) [67]. Studies conducted in recent years have identified the LHb as a source of anti-reward signals that plays an important role in determining the reward-related activity of DA neurons [18, 30, 68–70]. The firing patterns of glutamatergic LHb neurons mirror those of DA cells: spike activity increases in LHb neurons in the absence of predicted reward and decreases upon delivery of reward [69, 70]. Furthermore, electrical stimulation of the LHb inhibits the vast majority of DA neurons [69, 71, 72]. Such inhibition is not direct, but rather occurs through the stimulation of neurons in the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) [73]. The RMTg sends GABAergic inhibitory projections to the VTA and substantia nigra [54, 74, 75] and provides tonic inhibition of DA cells [30]. Similarly to the LHb, RMTg neurons are phasically activated by aversive stimuli and inhibited by natural rewards like food or reward predictive stimuli [54].

Although it is currently unknown whether the MHb contributes directly to the regulation of monoamine transmission, the literature suggests an involvement of the MHb/IPN axis with brain reward areas. Electrical stimulation of the MHb and the fasciculus retroflexus, the primary efferent pathway of the MHb, produces rewarding effects [76], and most stimulant drugs of abuse cause axonal degeneration in the lateral habenula and the fasciculus retroflexus. In particular, nicotine causes degeneration of neurons in the portion of the fasciculus retroflexus that connects the MHb to the IPN [77, 78]. A recent report suggests that α5-containing nAChRs in the MHb are key to the control of the amounts of nicotine self-administered as α5−/− mice continue to self-administer nicotine at doses that normally elicit strong aversion in wild type animals [79, 80]. However, lentiviral-based re-expression of the α5 subunit in the MHb or the IPN is sufficient to bring nicotine self-administration back to wild type levels [80]. Additionally, blocking cholinergic transmission in either the MHb or IPN is sufficient to precipitate somatic signs of nicotine withdrawal [81]. Taken together, these data suggest a prominent role of the MHb/IPN axis in nicotine dependence because of its involvement in mediating nicotine’s aversive effects and somatic symptoms of withdrawal.

2.4 Nicotine induced neuroadaptations

Nicotine dependence is accompanied by neuroadaptive changes that occur especially in the circuits underlying emotion and motivation [23, 82]. Neuronal nAChR upregulation is an important adaptive change and a major contributor to the addictive properties of nicotine [83–86]. Nicotine desensitizes nAChRs and renders them unresponsive and this phenomenon drives an increase in receptor levels as part of an attempt to maintain circuit-level homeostasis [87–89]. Upregulation of nAChRs is the product of several concurrent mechanisms, including changes in receptor assembly, trafficking, and degradation [18, 90]. Isomerization of surface nAChRs to high-affinity nicotinic sites has also been proposed to result from prolonged nicotine exposure [91, 92]. Relevant to the understanding of the neuroadaptations produced by nicotine is the fact that nAChR upregulation differs among receptor subtypes, varies among brain regions for the same subtype, and even depends on the contingency of nicotine administration [9, 90, 93]. Because of this phenomenon, the way in which cholinergic inputs modulate neurotransmitter release is completely altered.

Besides altering cholinergic function, repeated nicotine exposure produces heterologous adaptations. For example, nicotine increases AMPA/NMDA current ratios (a hallmark of long-term potentiation) at DA neurons [94–96] and other locations involved in drug-associated memory [97–99]. In the NAcc, nicotine leads to an increase in high affinity DA D2 receptors [100]. Such a phenomenon is analogous to that observed upon cocaine exposure, which leads to an increase in G-protein coupled DA D2 receptors and consequent DA supersensitivity in cocaine-treated animals [101]. A similar form of plasticity might occur during nicotine exposure. Nicotine self-administration also decreases expression of the cystine-glutamate exchanger, xCT, in the NAcc and VTA, and decreases the glial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, in the NAcc [102]. Synaptic function might also be altered by changes in the turnover of scaffolding proteins, a phenomenon reflecting nicotine’s partial inhibition of proteasomal function [86, 103, 104].

Another system that is affected by nicotine exposure is the endogenous opioid system [105–107]. The endogenous opioid system influences both negative and positive motivational and affective states [108]. Opioid peptides affect DA function in the VTA and the striatum. In particular, dynorphins decrease and enkephalins increase DA release [109–115]. Conversely, DA controls the synthesis of striatal dynorphin and enkephalin by affecting their mRNA levels [106, 116]. Nicotine affects these system-level and cellular interactions by altering synthesis and release of opioid peptides in a time- and peptide-specific fashion [36]. The ensuing plasticity participates in the mechanisms that maintain nicotine consumption but also participate in the nicotine-withdrawal syndrome [7, 106]. What we discussed above are examples of the complex changes produced by nicotine. As nAChR activation affects the release of virtually every major neurotransmitter [106, 117, 118], chronic nicotine exposure is likely to cause global alterations in brain neurotransmission. These complex, within-system and between-system adaptations create a new equilibrium that requires the presence of nicotine to be maintained.

3. Nicotine Withdrawal: Definition, Neurobiology, Animals models

3.1 Definition of Nicotine Withdrawal

Withdrawal is a collection of affective and somatic symptoms that emerge a few hours after nicotine abstinence and reflect the imbalance in brain neurochemistry created by the absence of nicotine. Seven nicotine withdrawal symptoms were validated in a recent comprehensive review on the topic [119] and appear in the DSM-IV-TR [120]. The symptoms are irritability/anger/frustration, anxiety, depression/negative affect, concentration problems, impatience, insomnia, and restlessness. Other symptoms (including altered neurohormonal profiles, perturbations of learned behaviors, weight gain, decreased heart rate, constipation, and mouth ulcers) are also likely valid symptoms but require further study [119, 121, 122]. Many of these symptoms are common to other drugs of abuse, but weight gain and decreased heart rate appear to be more specific to nicotine withdrawal [123]. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms are typically reported to reach a peak within the first week of abstinence and taper off for the next 3–4 weeks [119, 124]. However, some reports indicate that symptoms can subside within 10 days [125], while others indicate that withdrawal symptoms may persist past 31 days [126, 127].

Nicotine withdrawal symptoms are highly variable between patients and can be quite severe, with increased severity of withdrawal being predictive of increased rates of relapse [25, 27, 128–130]. Powerful cravings also accompany withdrawal, which may be precipitated by the sight of a cigarette, or a situation/place associated with the act of smoking [131]. The emergence of negative affective symptoms, such as dysphoria, anxiety and irritability and, to a lesser extent, the somatic manifestations of withdrawal, serve as negative reinforcers that sustain the vicious cycle of addiction [23, 121, 132–134]. Continued use or relapse is therefore driven not only by the pursuit of hedonically positive effects but also the avoidance of negative states associated with withdrawal.

3.2 Neural Basis of Withdrawal

Abrupt cessation of nicotine alters the neurochemistry of the addicted brain, thus triggering the affective and somatic signs of withdrawal. Acute withdrawal from all major drugs of abuse, including nicotine, decreases activity of the mesolimbic DAergic system, [135–139] and the consequent decrease in accumbal DA levels is likely the main trigger of the withdrawal syndrome. The hypodopaminergic state associated with withdrawal is produced by both a reduction in DA release and an increase in DA re-uptake [140]. Increased DA re-uptake is due to upregulation of the DA transporter (DAT) [137, 141]. Interestingly, the deficits in DA transmission observed in the NAcc during withdrawal are paralleled by an increase in DA output in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [138]. Such increases in PFC DA release may be important in mediating some of the aversive aspects of nicotine withdrawal. Enhanced DA transmission in the PFC occurs during exposure to stressful and aversive stimuli [142–144], and contributes to anxiety-related behaviors [145, 146]. Anxiety and stress exert complex influences on all aspects of nicotine dependence, including the withdrawal syndrome. Due to its perceived calming effects, smoking is often used by smokers as a tool to attenuate stress and anxiety [147–149]. Anxiety is a symptom of withdrawal and it acts as a potent negative reinforcer that promotes smoking [120, 124, 150–152]. Besides being a product of nicotine withdrawal, stress and anxiety can exacerbate the symptoms of withdrawal, which leads to increased craving and relapse [151, 153–156].

The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), together with the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and the posterior shell of the NAcc is part of the “extended amygdala” [157]. This circuit and the HPA axis play crucial roles in the processing of the negative affective states associated with drug withdrawal [23, 24, 157]. Elevations in corticosterone and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) are observed during acute withdrawal from many drugs, including nicotine [21, 24]. CRF levels increase by >500% in the CeA after nicotine withdrawal is precipitated with the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine [158]. Injection of a CRF1 receptor antagonist into the CeA blunts anxiety-like behavior during nicotine withdrawal [158]. These data collectively suggest that smoking cessation rates could be improved by quelling anxiety with drugs that address the dysregulation of the stress response system observed during withdrawal.

As already discussed in section 2.4, nicotine-induced neuroadaptations occur at many brain sites and affect several neurotransmitter systems. Therefore, nicotine withdrawal is expected to disrupt many of the neurotransmitter and neuropeptide systems that had adapted to the chronic presence of the drug [132]. The opioid system, dynorphin in particular, seems to be engaged in the mechanisms of nicotine withdrawal [106]. Other candidates are the serotoninergic and the noradrenergic systems which are known to mediate the manifestations of withdrawal from other drugs of abuse [159–162].

3.3 Animal Models of Withdrawal

Animal models of nicotine deprivation are invaluable tools for the understanding of the molecular underpinning of nicotine withdrawal symptoms and provide a way to test potential smoking cessation agents. Rodents chronically exposed to nicotine undergo a characteristic withdrawal syndrome which develops spontaneously, after removing the nicotine source, or can be precipitated by administration of a nAChR antagonist such as mecamylamine [7, 11, 81, 163–166]. Several behavioral tests are available to explore both the somatic and affective dimensions of withdrawal. The distinction between somatic and affective symptoms originated from the notion that the somatic signs reflect mainly peripheral, “bodily” mechanisms in contrast with the affective symptoms which are produced by centrally based mechanisms [167, 168]. This distinction is still maintained although there is evidence that, besides a peripheral nAChR component, somatic signs might have a central component that reflects a dysphoric state of heightened irritability [166, 169].

The following section briefly describes the tests most commonly used to assess nicotine withdrawal symptoms in rodents. In addition, based on pharmacologic studies and the analysis of nAChR mutant mice, it provides a summary of the most recent advances in the understanding of the nAChR subtypes and the brain areas involved in the nicotine withdrawal syndrome.

3.3.1 Somatic signs of withdrawal

The somatic manifestations of nicotine withdrawal in rodents can be detected as an increase in several stereotypic behaviors. Somatic signs of withdrawal include chewing, teeth-chattering, shakes, tremors, writhing, palpebral ptosis, gasps, and yawns [7, 163]. The analysis of nAChR mutant mice has helped to identify the brain region and the nAChR subtypes that are responsible for the somatic manifestations of nicotine withdrawal (Table 2). Somatic withdrawal can be precipitated by mecamylamine microinjection into the MHb or the IPN, but not into hippocampus, cortex, or VTA [81]. The MHb/IPN express nAChRs comprising the α2 (IPN), α5, and/or β4 nAChR subunits and absence of any one of those nAChR subunits abolishes the somatic manifestations of nicotine withdrawal [11, 81, 170]. α7-containing nAChRs might contribute to, but are not necessary for, the somatic manifestation of nicotine abstinence [171]. Interestingly, somatic signs of withdrawal are preserved in mice lacking the β2 or the α6 nAChR subunits [11, 172] even though, as seen in section 3.3.2, those subunits are critical for other aspects of withdrawal. These studies demonstrate that the MHb/IPN axis and specific nAChRs expressed within that axis are critical for at least the somatic signs of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome. In combination with the data showing that a circuit comprising the MHb and IPN is involved in controlling the intake of normally aversive doses of nicotine [80], the results suggest that, similarly to the LHb, the MHb may process signals with aversive valence.

Table 2.

Effect of nAChR Subunits on Rodent Models of Nicotine Withdrawal

| Signs | Effect | No Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Somatic |

α2 X [81] α5 ↓ or X [81, 170] α7 ↓ [165, 171] β4 X [11] |

α6 [172] α7 [170, 286] β2 [11] |

|

Affective Anxiety-related Behavior Attention Tasks (5-CSRTT) Intracranial Self Stimulation Conditioned Place Aversion Trace Fear Conditioning |

α6 X dd [172] β2 X EPoa [170] |

α5 [170] α7 [170] |

| --- | α7 [206] | |

| α5 ↓ [80] | α7 [287] | |

| α6 X dd [172] β2 X [170] |

α5 [170] α7 [170] |

|

| β2 X [201] | α7 [201] |

X = Withdrawal phenotype abolished; ↓ = Withdrawal phenotype diminished; EPoa = effect seen in the elevated plus maze, open arm time only; dd = dose dependent

3.3.2 Affective/cognitive symptoms of withdrawal

Affective symptoms such as anhedonia (inability to find pleasure in previously enjoyable activities), anxiety, and irritability are some of the most commonly reported manifestations of nicotine withdrawal in humans [119]. Affective signs of withdrawal can also be examined in rodents using behavioral paradigms that test for anhedonia, conditioned place aversion, anxiety, and conditioned fear [7, 165–167, 173].

Reward/Anhedonia

Intracranial self stimulation is a well established experimental procedure used to measure reward [174, 175]. Rodents will repeatedly self stimulate in reward-related areas such as the posterior lateral hypothalamus and the VTA where changes in thresholds for self stimulation can be monitored [167, 174, 176]. The threshold for intracranial self stimulation decreases with increased function of the brain reward systems and increases when activity in the same centers is reduced. Drugs of abuse, including nicotine, lower reward thresholds [174, 177–179]. The effects of nicotine are long lasting and are blocked by nicotinic, but not muscarinic, antagonists [178–181]. Like many of the effects of nicotine, reward threshold also presents a U-shaped dose-response curve: at higher doses of nicotine the reward threshold increases above baseline. This effect is dependent upon the α5 nAChR subunit in the MHb, since a rat will maintain a decreased reward threshold at higher doses when α5 is knocked down with lentiviral vector-based shRNA [80].

Withdrawal from drugs of abuse leads to decreased function of the reward system and changes ICSS thresholds [175, 182]. Such a phenomenon is thought to represent a negative affective state associated with withdrawal. Rats undergoing spontaneous withdrawal from chronic nicotine treatment show a dramatic increase in reward thresholds [167]. Normally neutral stimuli, such as a light or a tone, will also increase ICSS thresholds if that stimulus is paired with withdrawal from nicotine [183]. This phenomenon indicates that environmental cues associated with abstinence from nicotine may reduce the function of brain reward centers.

Conditioned Place Aversion

Conditioned place aversion (CPA) is a paradigm designed to test an animal’s drive to avoid contextual cues associated with a negative affect. Animals chronically treated with nicotine are confined in one of two chambers of the CPA apparatus while experiencing nicotine withdrawal symptoms triggered by the injection of a nAChR antagonist. On a different day, the same mice are injected with saline and exposed to the other chamber of the CPA apparatus. During training, associations are made between the negative affective state produced by withdrawal and the withdrawal-paired chamber so that exposure to the apparatus on testing day triggers avoidance of the compartment associated with the withdrawal effects. Both the α4β2 nAChR antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) and mecamylamine produce CPA in nicotine-treated rats, although the doses needed to elicit the behavior may be higher than those required to increase ICSS thresholds [184–188]. These differences may signify the existence of different mechanisms for ICSS and CPA, but might also reflect strain-specific differences [186, 187]. Pharmacological studies in nAChR null mice indicate that β2-containing and α6-containing nAChRs are necessary for CPA, but neither the α5, nor the α7 subunits affect CPA behavior [170, 172, 189].

Anxiety-related behaviors

Nicotine withdrawal can elicit anxiety-like behaviors in mice [190–192]. The most common paradigm used to observe these behaviors is the elevated plus maze (EPM) [193]. When nicotine withdrawal is precipitated in mice or rats, the animals spend significantly less time in the open arms of the EPM than saline-treated mice, a phenomenon that signals increased anxiety [165, 194]. In the open field paradigm, mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal is accompanied by a dramatic increase in thigmotaxis, i.e. an increase in the time spent in the periphery of the open field [195, 196]

Other animal models of anxiety are also altered by nicotine withdrawal. The light-dark box is a testing paradigm in which a mouse is placed in a novel environment that contains a brightly lit compartment and a dark compartment. The mouse will preferentially remain in the dark half of the box. The amount of time spent in the lit half and the time it takes for the mouse to cross into the lit half are measures of anxiety-like behaviors. Mice undergoing spontaneous withdrawal from nicotine will spend less time in the lit compartment relative to nicotine naïve mice [190, 192]. The influence of various nAChR subtypes on withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behaviors has not been examined exhaustively. So far, it has been established that the β2 and α6 nAChR subunits are necessary for increased anxiety during withdrawal [170, 172], whereas, α5 and α7 may not be required [170].

Fear Conditioning

Trace fear conditioning is a conditioning paradigm in which the conditioned stimulus (CS) is presented and then terminated with a time interval before the unconditioned stimulus (US) is applied [197]. Cued delay fear conditioning, in which the CS co-terminates with the US, is known to be hippocampus independent, whereas trace fear conditioning is dependent on the hippocampal circuitry [197]. Nicotine is known to enhance hippocampus-dependent contextual and cued trace fear conditioning, but not cued delay fear conditioning [198]. This enhancement by nicotine requires β2-containing but not α7-containing nAChRs [199]. Also, systemic administration of NMDA receptor antagonists inhibits acquisition of contextual fear conditioning [200]. This effect is ameliorated by co-administration of systemic nicotine acting at α4β2-containing nAChRs, as indicated by antagonism with DHβE [200].

As with many effects of acute or chronic drug use, the withdrawal syndrome often results in an opposite effect. Since nicotine enhances trace fear conditioning, one could expect withdrawal to cause a deficit in the same paradigm. Raybuck and Gould [201] demonstrated that spontaneous withdrawal from chronic nicotine leads to deficits in the acquisition of trace fear conditioning. Withdrawal precipitated by DHβE, but not methyllycaconitine (MLA), led to a similar deficit, implicating high-affinity receptors such as those containing the α4, and the β2/β4 nAChR subunits. Confirming this result, β2-null mice were not observed to have a deficit in trace fear conditioning upon spontaneous nicotine withdrawal [201].

Five-choice serial reaction time task

Tobacco deprivation impairs attention and cognitive abilities within 12 h of smoking cessation [202–204]. Models of attention might be useful to test this dimension of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome. The five-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT) is a visual attention task [205] that can reliably detect cognitive aspects of nicotine withdrawal [206, 207]. Significant deficits in sustained attention were seen after spontaneous withdrawal from nicotine in male rats [206], as well as during withdrawal precipitated with DHβE [206]. The α7 nAChR antagonist MLA failed to precipitate attention deficits in nicotine-treated rats [206], suggesting that α4β2-containing, but not α7-containing nAChRs are important for 5-CSRTT.

4. Pharmacotherapy of nicotine addiction

4.1 Current therapies

To be successful, anti-smoking strategies need to reduce the motivation to smoke and the physiological and psychomotor symptoms experienced during a quit attempt. All current therapeutic strategies, albeit with different mechanisms, address the hypodopaminergic state produced by withdrawal in the VTA. Other mechanisms of action might also contribute to their ability to promote smoking cessation.

Nicotine replacement therapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) has been the primary pharmacologic aid for tobacco cessation. As nicotine is the principal addictive component of cigarettes and other tobacco products, supplementing the user with nicotine during abstinence will ease the transition from smoking to complete abstinence by relieving withdrawal and nicotine craving [6, 208]. Because nicotine undergoes first pass metabolism in the liver, the bioavailability of nicotine administered per os is reduced. To avoid this problem, nicotine replacement products are formulated for absorption through the oral mucosa (chewing gum, lozenges, sublingual tablets, inhaler) or the skin (transdermal patches). Regardless of the route of administration (gum, patch, nasal spray, or inhaler), NRT decreases withdrawal scores by a similar degree [209]. NRT roughly doubles quit rates compared to placebo, but a large percentage of subjects relapses to smoking within 6 to 12 months [210, 211]. For smokers who declare unwillingness or inability to attempt an abrupt quit, the 12-month sustained abstinence success rate is 5.3% with NRT versus approximately 2.6% with placebo. In smokers willing to attempt an abrupt quit with NRT, the success rate is around 16% with NRT versus 10% with placebo [212]. Newer, more targeted pharmacotherapies have led to significant improvements in aiding tobacco cessation rates [213].

Bupropion

Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant and smoking cessation aid that exerts its actions by targeting multiple neurotransmitter systems [214]. Inhibition of catecholamine reuptake is one of bupropion’s mechanisms of action [215]. Microdialysis studies indicate that bupropion treatment increases extracellular concentrations of DA and norepinephrine (NE) in the hypothalamus, PFC, and NAcc [216]. The drug may also function by increasing NE levels in the dorsal raphe nucleus, thus leading to increased serotonin (5-HT) levels [217]. Besides reducing NE, DA, and 5-HT reuptake, the drug increases the activity of vesicular monoamine transporters [214]. Bupropion also functions as a non-competitive antagonist at many nAChR subtypes [218]. Bupropion inhibits the function of α3β2-, α4β2-, and α7-nAChRs heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes [219]. It also non-competitively inhibits carbamylcholine-induced 86Rb+ efflux from human neuroblastoma cells expressing α3β4-containing nAChRs [218]. α3β4-containing nAChRs are believed to play a major role in nicotine-evoked NE release from the hippocampus [220, 221]. In addition, the α3 and β4 nAChR subunits are expressed at high levels in the MHb/IPN axis [222–224], which, as discussed in section 2.3, is emerging as a brain circuit involved in the processing of anti-reward stimuli and nicotine withdrawal [11, 80, 222].

Preclinical studies suggest that bupropion and nicotine might exert similar systems level effects. Both drugs are psychomotor stimulants [225, 226] and both increase catecholamine concentrations in midbrain limbic regions [214, 227]. In addition, both nicotine and bupropion serve as primary reinforcers in non-human subjects [228] and increase responding for reinforcing non-drug stimuli [229–231]. Therefore, the anti-smoking properties of bupropion may depend on its ability to substitute some of the psychomotor and/or reinforcement-related effects of nicotine [232]. Bupropion improves rates of abstinence to 14–18% of subjects [150, 233], which are further augmented to 29% when the drug is combined with NRT [210, 234, 235].

Varenicline

Varenicline is the third medication, besides NRT and bupropion, to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for smoking cessation. It is a derivative of cytisine, a plant alkaloid with selective affinity and partial agonism for α4β2 nAChRs [236–238]. Varenicline has been touted as being effective through its partial agonism of α4β2 nAChRs. This effect is thought to decrease withdrawal and cravings [239]. Varenicline can block nicotine-induced decreases in brain stimulation thresholds, suggesting that it makes smoking less enjoyable [240]. Varenicline’s effect is removed by pre-treatment with the non-selective nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine, or the α4-containing nAChR specific antagonist DHβE. On the other hand, the α7-specific antagonist, MLA, has no effect on reward thresholds [240]. Besides acting at α4β2-containing nAChRs, varenicline has significant effects at other nAChR subtypes. It acts as a partial agonist at α3β4-, α2-, and α6-containing nAChRs, and a full agonist at α7 nAChRs [238]. Varenicline’s interactions with α3β4-, α2-, or α6-containing nAChRs might also contribute to its therapeutic effects given the role of those receptors in both the rewarding and/or aversive effects of nicotine [11, 13, 80, 81].

Two large, randomized, placebo-controlled studies released in 2006 related the efficacy of varenicline to that of bupropion in aided smoking cessation [233, 241]. Nearly one quarter (21–23%) of patients taking varenicline for a short period of time (12 weeks) maintained abstinence at 52 weeks of follow-up. This represents a significant improvement over sustained-release bupropion (14–16%) and placebo (8–10%). Further analyzing the mechanisms of this effect, negative affect and craving associated with abstinence were decreased in patients taking varenicline relative to placebo [233]. However, the drug had no significant effect on restlessness, insomnia, or increased appetite. Gonzales and colleagues [241] found a similar decrease in negative affect, but also found a significant decrease in restlessness in patients taking varenicline. Individuals who relapsed derived less enjoyment from smoking while taking varenicline [241]. A very recent review of the literature suggests that, overall, varenicline works better than bupropion as a smoking cessation aid, although it is not clear how superior it is to NRT in the long term. Two open label, randomized controlled trial were unable to confirm significant improvements with varenicline over NRT in continuous abstinence rates at 52 weeks following short term treatment [213, 242, 243]. However, it should be noted that the 52 week abstinence rate for NRT was found to be 20.4%, higher than most previously reported rates, while varenicline maintained the usual reported rate (26.1%) [242].

Although bupropion and varenicline were proven safe in clinical trials, safety concerns have arisen based on post-marketing reports that led to the addition of warnings in the prescribing information of the two drugs. Although a causal relationship has not been established, serious adverse events in patients treated with bupropion or varenicline include changes in behavior, depression, self-injurious thoughts, and suicidal behavior [234, 244]. Because long-term tobacco use causes morbidity in a high percentage of subjects and ends up killing half of all long-term smokers, the benefits of the two drugs outweigh the risks of serious adverse events in a small percentage of subjects. However, the occurrence of serious side effects and the relatively small, long-term rates of abstinence in smokers serve as an impetus for the development of new, safer therapeutic interventions [239, 245].

Nicotine vaccine

All the previously described pharmacotherapies require compliance to maintain efficacy. Nicotine vaccination offers a promising, more permanent approach to aid the willing addict in cessation attempts. Exposure to nicotine conjugated to immunogenic proteins (e.g. cholera toxin b, a virus-like particle, and Pseudomonas exotoxin A) leads to production of IgGs, some of which will be targeted against nicotine [239, 246]. Anti-nicotine antibodies will bind to nicotine with high affinity and specificity, thus preventing or at least slowing nicotine’s entry into the brain [247]. Decreasing the rate of absorption and the actions of an addictive drug on its targets reduce its rewarding effects and may aid in quitting [247, 248]. A recent preclinical study demonstrated the efficacy of this approach [249]. After immunization using Pseudomonas exoprotein A conjugated to nicotine, rats exposed to cigarette smoke demonstrated a significant increase in serum nicotine levels, indicating prevention of nicotine entry into the brain. With a 10 minute nose-only exposure, modeling one cigarette, brain levels of nicotine were reduced by 90% in the vaccinated animals. After a 2 hour whole body exposure to smoke, a 35% reduction in brain nicotine was detected [249]. These results confirm other studies using non-inhalation routes of administration [250–252]. Early phase 1/2 clinical trials in humans have demonstrated drug safety, effective immunogenicity, and promising increases in abstinence rates, especially among individuals with higher levels of anti-nicotine IgGs [253–256]. Whether a nicotine vaccine is going to be effective for real-world use remains an open question. The results of ongoing clinical trials are eagerly awaited.

5. Conclusions

Chronic exposure to nicotine produces neuroadaptations in a host of neurotransmitter and neuropeptide systems. Those neuroadaptations are responsible for the psychological and behavioral symptoms associated with nicotine abstinence and make nicotine addiction so hard to break. Driven by preclinical studies in various animal models as well as human studies, the improved understanding of the mechanisms involved in nicotine dependence has led to new treatments. Targeting of the α4β2 nAChR subtype with varenicline significantly improves abstinence rates, and recent studies provide additional nAChR targets that might help to design more effective pharmacological agents. A multipronged approach that could simultaneously address the dysfunction of the DAergic system, the deficits in executive control over the drug, and the connection between stress/anxiety and nicotine consumption would indeed offer the best relief from the symptoms of withdrawal. Finally, a nicotine vaccine, if effective, could provide a paradigm shift in the treatment of nicotine dependence. The concerted effort of basic scientists and clinicians will be needed to stop the global epidemic of tobacco-related disease and premature mortality.

Acknowledgments

Work in the De Biasi lab is supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA017173 & DA024385), the National Cancer Institute (U19 CA148127), and the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas (RP100443 and RP101120). M. P. is the recipient of a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Student Research Fellowship.

The authors acknowledge the joint participation of the Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation through its direct engagement in the continuous active conduct of medical research in conjunction with Baylor College of Medicine and the ‘Genomic, Neural, Preclinical Analysis for Smoking Cessation’ Project for the Dan L Duncan Cancer Center

Abbreviations

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- BNST

bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- CeA

central nucleus of the amygdala

- 5-CSRTT

five-choice serial reaction time task

- CPA

conditioned place aversion

- CRF

corticotropin-releasing factor

- DA

dopamine

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- EPM

elevated plus maze

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptophan

- ICSS

intracranial self-stimulation

- LDT

laterodorsal tegmentum

- MLA

methyllycaconitine

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- NAcc

nucleus accumbens

- NE

norepinephrine

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PPT

pedunculopontine tegmentum

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged >or=18 years --- United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Benefits of smoking cessation for longevity. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):990–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2295–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Biasi M, Salas R. Influence of neuronal nicotinic receptors over nicotine addiction and withdrawal. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233(8):917–29. doi: 10.3181/0712-MR-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotti C, et al. Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78(7):703–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salas R, et al. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 5 mediates acute effects of nicotine in vivo. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;63:1059–1066. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salas R, Pieri F, De Biasi M. Decreased signs of nicotine withdrawal in mice null for the beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Neurosci. 2004;24(45):10035–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1939-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exley R, et al. Alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2158–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Exley R, et al. Distinct contributions of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit {alpha}4 and subunit {alpha}6 to the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bierut LJ. Genetic vulnerability and susceptibility to substance dependence. Neuron. 2011;69(4):618–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. The role of sensory perception in the development and targeting of tobacco products. Addiction. 2007;102(1):136–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samet JM. The 1990 Report of the Surgeon General: The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142(5):993–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. 2010. Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Biasi M, Dani JA. Reward, Addiction, Withdrawal to Nicotine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albuquerque EX, et al. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wonnacott S, et al. Nicotinic receptors modulate transmitter cross talk in the CNS: nicotinic modulation of transmitters. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30(1–2):137–40. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:1:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koob G, Kreek MJ. Stress, Dysregulation of Drug Reward Pathways, and the Transition to Drug Dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1149–1159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenny PJ, Markou A. Neurobiology of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70(4):531–49. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):217–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychol Med. 1989;19(4):981–5. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Profiles in discouragement: two studies of variability in the time course of smoking withdrawal symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(2):238–51. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.al’Absi M, et al. Prospective examination of effects of smoking abstinence on cortisol and withdrawal symptoms as predictors of early smoking relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(3):267–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275(5306):1593–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wise RA. Roles for nigrostriatal--not just mesocorticolimbic--dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(10):517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikemoto S. Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: A neurobiological theory. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35(2):129–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz W. Dopamine signals for reward value and risk: basic and recent data. Behav Brain Funct. 2010;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron. 2010;68(5):815–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blum K, et al. Reward Circuitry Dopaminergic Activation Regulates Food and Drug Craving Behavior. Curr Pharm Des. 2011 doi: 10.2174/138161211795656819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liechti ME, Markou A. Role of the glutamatergic system in nicotine dependence : implications for the discovery and development of new pharmacological smoking cessation therapies. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(9):705–24. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wooters TE, Bevins RA, Bardo MT. Neuropharmacology of the interoceptive stimulus properties of nicotine. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2009;2(3):243–55. doi: 10.2174/1874473710902030243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berrendero F, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms involved in nicotine dependence and reward: participation of the endogenous opioid system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(2):220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maldonado R, Berrendero F. Endogenous cannabinoid and opioid systems and their role in nicotine addiction. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11(4):440–9. doi: 10.2174/138945010790980358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wanat MJ, et al. Phasic dopamine release in appetitive behaviors and drug addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2009;2(2):195–213. doi: 10.2174/1874473710902020195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grace AA, et al. Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(5):220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Laterodorsal tegmental projections to identified cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483(2):217–35. doi: 10.1002/cne.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maskos U. The cholinergic mesopontine tegmentum is a relatively neglected nicotinic master modulator of the dopaminergic system: relevance to drugs of abuse and pathology. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(S1):S438–S445. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maskos U. Role of endogenous acetylcholine in the control of the dopaminergic system via nicotinic receptors. J Neurochem. 2010;114(3):641–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalivas PW. Neurotransmitter regulation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18(1):75–113. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90008-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steffensen SC, et al. Electrophysiological characterization of GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1998;18(19):8003–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-08003.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walaas I, Fonnum F. Biochemical evidence for gamma-aminobutyrate containing fibres from the nucleus accumbens to the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area in the rat. Neuroscience. 1980;5(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Threlfell S, Cragg SJ. Dopamine signaling in dorsal versus ventral striatum: the dynamic role of cholinergic interneurons. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:11. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Rover M, et al. Cholinergic modulation of nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(12):2279–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woolf NJ. Cholinergic systems in mammalian brain and spinal cord. Prog Neurobiol. 1991;37(6):475–524. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90006-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Contant C, et al. Ultrastructural characterization of the acetylcholine innervation in adult rat neostriatum. Neuroscience. 1996;71(4):937–47. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calabresi P, et al. Acetylcholine-mediated modulation of striatal function. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(3):120–6. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klink R, et al. Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. J Neurosci. 2001;21(5):1452–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sulzer D. How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission. Neuron. 2011;69(4):628–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(1):1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jhou TC, et al. The rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), a GABAergic afferent to midbrain dopamine neurons, encodes aversive stimuli and inhibits motor responses. Neuron. 2009;61(5):786–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science. 2004;303(5666):2040–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schultz W. Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:259–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schultz W. Behavioral dopamine signals. Trends in Neurosciences. 2007;30(5):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brischoux F, et al. Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(12):4894–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Nucleus accumbens neurons are innately tuned for rewarding and aversive taste stimuli, encode their predictors, and are linked to motor output. Neuron. 2005;45(4):587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Picciotto MR. Nicotine as a modulator of behavior: beyond the inverted U. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24(9):493–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00230-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hutchison MA, Riley AL. Adolescent exposure to nicotine alters the aversive effects of cocaine in adult rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30(5):404–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benowitz NL, Jacob P., 3rd Trans-3′-hydroxycotinine: disposition kinetics, effects and plasma levels during cigarette smoking. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(1):53–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kassel JD, et al. Smoking topography in response to denicotinized and high-yield nicotine cigarettes in adolescent smokers. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dani JA, Kosten TR, Benowitz NL. The pharmacology of nicotine and tobacco. In: Ries RK, et al., editors. Principles of Addiction Medicine. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. pp. 179–91. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winter C, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the lateral habenula improves depressive-like behavior in an animal model of treatment resistant depression. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216(1):463–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Geisler S, Trimble M. The lateral habenula: no longer neglected. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(6):484–9. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(7):503–13. doi: 10.1038/nrn2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matsumoto M. Role of the lateral habenula and dopamine neurons in reward processing. Brain Nerve. 2009;61(4):389–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1111–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hikosaka O, et al. Habenula: crossroad between the basal ganglia and the limbic system. J Neurosci. 2008;28(46):11825–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3463-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Christoph GR, Leonzio RJ, Wilcox KS. Stimulation of the lateral habenula inhibits dopamine-containing neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the rat. J Neurosci. 1986;6(3):613–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-03-00613.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ji H, Shepard PD. Lateral Habenula Stimulation Inhibits Rat Midbrain Dopamine Neurons through a GABAA Receptor-Mediated Mechanism. J Neurosci. 2007;27(26):6923–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0958-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perrotti LI, et al. DeltaFosB accumulates in a GABAergic cell population in the posterior tail of the ventral tegmental area after psychostimulant treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21(10):2817–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jhou TC, et al. The mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus: A structure targeted by the lateral habenula that projects to the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and substantia nigra compacta. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513(6):566–96. doi: 10.1002/cne.21891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Balcita-Pedicino J, et al. rostromedial mesopontine tegmentum as a relay between the lateral habenula and dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area: ultrastructural evidence in the rat. 2009 Annual Meeting Society for Neuroscience; 2009; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sutherland RJ, Nakajima S. Self-stimulation of the habenular complex in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1981;95(5):781–91. doi: 10.1037/h0077833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ellison G, et al. The neurotoxic effects of continuous cocaine and amphetamine in Habenula: implications for the substrates of psychosis. NIDA Res Monogr. 1996;163:117–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ellison G. Neural degeneration following chronic stimulant abuse reveals a weak link in brain, fasciculus retroflexus, implying the loss of forebrain control circuitry. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12(4):287–97. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fowler C, Kenny P. Intravenous nicotine self-administration in wildtype and α5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knockout mice. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting; 2009; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fowler CD, et al. Habenular alpha5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature. 2011;471(7340):597–601. doi: 10.1038/nature09797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salas R, et al. Nicotinic receptors in the habenulo-interpeduncular system are necessary for nicotine withdrawal in mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29(10):3014–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solomon RL, Corbit JD. An opponent-process theory of motivation. I. Temporal dynamics of affect. Psychol Rev. 1974;81(2):119–45. doi: 10.1037/h0036128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wonnacott S. The paradox of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor upregulation by nicotine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11(6):216–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90242-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marks MJ, et al. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit RNA after chronic nicotine treatment. J Neurosci. 1992;12(7):2765–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Buisson B, Bertrand D. Chronic exposure to nicotine upregulates the human (alpha)4((beta)2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor function. J Neurosci. 2001;21(6):1819–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01819.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rezvani K, et al. Nicotine regulates multiple synaptic proteins by inhibiting proteasomal activity. J Neurosci. 2007;27(39):10508–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3353-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fenster CP, et al. Upregulation of surface alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors is initiated by receptor desensitization after chronic exposure to nicotine. J Neurosci. 1999;19(12):4804–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04804.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dani JA, Heinemann S. Molecular and cellular aspects of nicotine abuse. Neuron. 1996;16(5):905–8. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Picciotto MR, et al. It is not “either/or”: activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84(4):329–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lester HA, et al. Nicotine is a selective pharmacological chaperone of acetylcholine receptor number and stoichiometry. Implications for drug discovery. Aaps J. 2009;11(1):167–77. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Buisson B, Bertrand D. Nicotine addiction: the possible role of functional upregulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23(3):130–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vallejo YF, et al. Chronic nicotine exposure upregulates nicotinic receptors by a novel mechanism. J Neurosci. 2005;25(23):5563–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5240-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gentry CL, Lukas RJ. Regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor numbers and function by chronic nicotine exposure. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1(4):359–85. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gao M, et al. Mechanisms involved in systemic nicotine-induced glutamatergic synaptic plasticity on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2010;30(41):13814–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1943-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Placzek AN, Zhang TA, Dani JA. Nicotinic mechanisms influencing synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30(6):752–60. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Saal D, et al. Drugs of abuse and stress trigger a common synaptic adaptation in dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2003;37(4):577–82. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dani JA, De Biasi M. Cellular mechanisms of nicotine addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70(4):439–46. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(11):844–58. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tang J, Dani JA. Dopamine Enables In Vivo Synaptic Plasticity Associated with the Addictive Drug Nicotine. Neuron. 2009;63(5):673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Novak G, Seeman P, Le Foll B. Exposure to nicotine produces an increase in dopamine D2(High) receptors: a possible mechanism for dopamine hypersensitivity. Int J Neurosci. 2010;120(11):691–7. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2010.513462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Briand LA, et al. Cocaine self-administration produces a persistent increase in dopamine D2 High receptors. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(8):551–6. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Knackstedt LA, et al. The role of cystine-glutamate exchange in nicotine dependence in rats and humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(10):841–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hwang YY, Li MD. Proteins differentially expressed in response to nicotine in five rat brain regions: identification using a 2-DE/MS-based proteomics approach. Proteomics. 2006;6(10):3138–53. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rezvani K, et al. UBXD4, a UBX-containing protein, regulates the cell surface number and stability of alpha3-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29(21):6883–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4723-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Berrendero F, et al. Nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and physical dependence are decreased in mice lacking the preproenkephalin gene. J Neurosci. 2005;25(5):1103–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3008-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hadjiconstantinou M, Neff NH. Nicotine and endogenous opioids: Neurochemical and pharmacological evidence. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(7–8):1209–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Trigo JM, et al. The endogenous opioid system: a common substrate in drug addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(3):183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Steiner H, Gerfen CR. Role of dynorphin and enkephalin in the regulation of striatal output pathways and behavior. Exp Brain Res. 1998;123(1–2):60–76. doi: 10.1007/s002210050545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Devine DP, et al. Differential involvement of ventral tegmental mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors in modulation of basal mesolimbic dopamine release: in vivo microdialysis studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266(3):1236–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Opposite effects of mu and kappa opiate agonists on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and in the dorsal caudate of freely moving rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244(3):1067–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Longoni R, et al. (D-Ala2)deltorphin II: D1-dependent stereotypies and stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1991;11(6):1565–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01565.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pentney RJ, Gratton A. Effects of local delta and mu opioid receptor activation on basal and stimulated dopamine release in striatum and nucleus accumbens of rat: an in vivo electrochemical study. Neuroscience. 1991;45(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. The effects of opioid peptides on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1990;55(5):1734–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Identification of the opioid receptor types mediating beta-endorphin-induced alterations in dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;190(1–2):177–84. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94124-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Opposing tonically active endogenous opioid systems modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(6):2046–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Angulo JA, McEwen BS. Molecular aspects of neuropeptide regulation and function in the corpus striatum and nucleus accumbens. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1994;19(1):1–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kenny PJ. Tobacco dependence, the insular cortex and the hypocretin connection. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;97(4):700–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Picciotto MR. Common aspects of the action of nicotine and other drugs of abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(1–2):165–72. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(3):315–27. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: 2000. text revision ed. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the ‘dark side’ of drug addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1442–4. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Buchhalter AR, Fant RV, Henningfield JE. Nicotine. In: Sibley DR, et al., editors. Handbook of contemporary neuropharmacology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. pp. 535–566. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hughes JR, Higgins ST, Bickel WK. Nicotine withdrawal versus other drug withdrawal syndromes: similarities and dissimilarities. Addiction. 1994;89(11):1461–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hughes JR, et al. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. A replication and extension. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(1):52–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shiffman S, et al. Natural history of nicotine withdrawal. Addiction. 2006;101(12):1822–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gilbert DG, et al. EEG, physiology, and task-related mood fail to resolve across 31 days of smoking abstinence: relations to depressive traits, nicotine exposure, and dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7(4):427–43. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gilbert DG, et al. Mood disturbance fails to resolve across 31 days of cigarette abstinence in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):142–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Piasecki TM, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: II. Improved tests of withdrawal-relapse relations. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(1):14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Piasecki TM, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: III. Correlates of withdrawal heterogeneity. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11(4):276–85. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Piasecki TM, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: I. Abstinence distress in lapsers and abstainers. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(1):3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shiffman S, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(4):531–45. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24(2):97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Piper ME, et al. Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment. Addiction. 2011;106(2):418–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Allen SS, et al. Craving, withdrawal, and smoking urges on days immediately prior to smoking relapse. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(1):35–45. doi: 10.1080/14622200701705076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hildebrand BE, et al. Reduced dopamine output in the nucleus accumbens but not in the medial prefrontal cortex in rats displaying a mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Brain Res. 1998;779(1–2):214–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rada P, Jensen K, Hoebel BG. Effects of nicotine and mecamylamine-induced withdrawal on extracellular dopamine and acetylcholine in the rat nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;157(1):105–10. doi: 10.1007/s002130100781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rahman S, et al. Neuroadaptive changes in the mesoaccumbens dopamine system after chronic nicotine self-administration: a microdialysis study. Neuroscience. 2004;129(2):415–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Carboni E, et al. Dissociation of physical abstinence signs from changes in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and in the prefrontal cortex of nicotine dependent rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58(1–2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Weiss F, et al. Basal extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens are decreased during cocaine withdrawal after unlimited-access self-administration. Brain Res. 1992;593(2):314–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91327-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Duchemin AM, et al. Increased expression of VMAT2 in dopaminergic neurons during nicotine withdrawal. Neurosci Lett. 2009;467(2):182–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hadjiconstantinou M, et al. Enhanced dopamine transporter function in striatum during nicotine withdrawal. Synapse. 2011;65(2):91–8. doi: 10.1002/syn.20820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Thierry AM, et al. Selective activation of mesocortical DA system by stress. Nature. 1976;263(5574):242–4. doi: 10.1038/263242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Inglis FM, Moghaddam B. Dopaminergic innervation of the amygdala is highly responsive to stress. J Neurochem. 1999;72(3):1088–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kawasaki H, et al. Single-neuron responses to emotional visual stimuli recorded in human ventral prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(1):15–6. doi: 10.1038/82850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]