Abstract

Designing and building multigene constructs is commonplace in synthetic biology. Yet functional successes at first attempts are rare because the genetic parts are not fully modular. In order to improve the modularity of transcription, we previously showed that transcription termination in vitro by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase could be made more efficient by substituting the standard, single, TΦ large (class I) terminator with adjacent copies of the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) small (class II) terminator. However, in vitro termination at the downstream VSV terminator was less efficient than at the upstream VSV terminator, and multigene overexpression in vivo was complicated by unexpectedly inefficient VSV termination within E. coli cells. Here, we address hypotheses raised in that study by showing that VSV or preproparathyroid hormone (PTH) small terminators spaced further apart can work independently (i.e. more efficiently) in vitro, and that VSV and PTH terminations are severely inhibited in vivo. Surprisingly, the difference between class II terminator function in vivo versus in vitro is not due to differences in plasmid supercoiling, as supercoiling had a minimal effect on termination in vitro. We therefore turned to TΦ terminators for “BioBrick” synthesis of a pentameric gene construct suitable for overexpression in vivo. This indeed enabled coordinated overexpression and copurification of five His-tagged proteins using the first construct attempted, indicating that this strategy is more modular than other strategies. An application of this multigene overexpression and protein copurification method is demonstrated by supplying five of the six E. coli translation factors required for reconstitution of translation from a single cell line via copurification, greatly simplifying the reconstitution.

Keywords: synthetic biology, gene expression, T7 RNA polymerase, transcription terminator, translation

Introduction

An important goal of synthetic biology is development of methods for modular construction of pre-designed multigene systems. Ideally, whether the genes are chromosomal or extra-chromosomal, whether they are clustered or not, whether they express proteins or just RNAs, and whether they express highly or lowly, their expression should be both reliable and coordinated. In current technology, as the number of genes increases from two to several, the systems generally become unwieldy and behave unpredictably (Kwok 2010). For example, successful programming of microbal enzyme pathways for synthesis of the anti-malarial drug artemisinin took 150-person years of work (Keasling 2010). As another example, take our recent balanced overexpression of five genes, both in vitro and in vivo, using small terminators for T7 RNA polymerase (T7 RNAP): achieving the in vivo result required troubleshooting unexpected results by redesigning the constructs (Du et al. 2009). Here, we test hypotheses proposed to explain our unexpected results, and then apply this new information to develop an improved method for multigene overexpression in vivo.

Applications of multigene expression pursued by our laboratory include scalable synthesis of purified translation systems (Du et al. 2009; Forster et al. 2001; Shimizu et al. 2001) and synthesis of a minimal cell (Forster and Church 2006; Jewett and Forster 2010). A simple plan for both of these projects is placement of all of the genes on a circular genome, with each gene being flanked by a promoter and a terminator for T7 RNAP (Watanabe et al. 2006). However, the tandem arrangement of 30 or so such genes may create problems due to known incomplete termination at each standard 100 bp class I terminator, TΦ (Macdonald et al. 1994) (~70% termination in vitro and in vivo (Studier and Moffatt 1986)), and due to potential recombination between many tandem copies of this large terminator during passage in vivo. Thus, we investigated the possible utility of the most efficient of the small class II T7 terminators in tandem to increase termination while decreasing recombination potential (Du et al. 2009). The most efficient known such terminator (~70% termination in vitro; untested in vivo (Lyakhov et al. 1998)) is the artificial, 18-bp terminator derived from Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV (Whelan et al. 1995)). Our initial design using one to three VSV terminators in tandem was effective in vitro for transcription termination and protein synthesis, as predicted from prior in vitro termination efficiencies. Unexpectedly, in contrast to in vitro, our results in vivo for protein overexpression from the same plasmid clones led us to conclude that run through transcription may be efficient in vivo (Du et al. 2009).

T7 RNAP is one of the most intensely studied and utilized enzymes in molecular biology. Yet, while class II termination has been well characterized in vitro (Nayak et al. 2008), there is little definitive in vivo information because termination efficiencies are difficult to measure in vivo in the presence of cellular RNA transcripts and in the face of highly active RNases. In the case of the only natural class II terminator, the T7 Concatemer Junction Sequence (CJ), there is some in vivo data. CJ function is apparently required for growth of T7 phage because mutant T7 RNAP that is defective in class II terminator recognition fails to support maturation or packaging of the phage (Lyakhov et al. 1997). But in vivo activity of CJ was difficult to ascertain when it was transplanted into the 3’ end of a gene upstream of a T7 promoter (Cheng and Goldman 2001; Harvey et al. 1999).

Adding to the complexity, results with one class II terminator may not be generalizable to other class II terminators despite their homologous sequences. For example, in vitro kinetics showed that at CJ, in addition to 25% termination by T7 RNAP, pausing occurred at 35% efficiency before continuing extension (Lyakhov et al. 1998). However, only termination, not pausing, occurred at an artificial class II terminator found in human preproparathyroid hormone (PTH; (Mead et al. 1986)). This lack of pausing at PTH was attributed to a longer run of encoded 3’-terminal U residues thought to destabilize the DNA-RNA hybrid (Lyakhov et al. 1998). Consistent with this hypothesis, the higher VSV termination efficiency than PTH correlates with an even longer run of U residues. Also noteworthy is a personal communication on page 18807 of (He et al. 1998): “Mead has found that utilization of the PTH terminator is decreased about 10-fold on a negatively supercoiled template as opposed to a linear template”. Given that plasmid DNA is negatively supercoiled in vivo and is relaxed in vitro either by nicking or linearization, this personal communication warranted further investigation as a possible explanation for our intriguing results with the homologous VSV terminator. But the VSV terminator apparently differs from the PTH terminator with regard to the effect of supercoiling because transcription of circular plasmid DNA containing the VSV terminator terminates efficiently in vitro (Whelan et al. 1995).

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructs

The construction and sequences of constructs 14, 15 and 24 in our Biobrick derivative of pET-24a (Novagen, Madison, WI) have been described (Du et al. 2009). The remaining constructs in Figs. 1, 4 and 5 were prepared in the same way using the stepwise BioBrick strategy (Knight 2003) in E. coli DH5α cells. Oligodeoxyribonucleotides (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were synthesized as BioBrick parts (flanked by EcoRI and XbaI and by SpeI and PstI sites) containing the T7 RNAP terminators VSV: TATCTGTTAGTTTTTTTC, PTH: ATGCTTGCCATCTGTTTTCTTGCAAG or TΦ: CTGCTAACAA AGCCCGAAAG GAAGCTGAGT TGGCTGCTGC CACCGCTGAG CAATAACTAG CATAACCCCT TGGGGCCTCT AAACGGGTCT TGAGGGGTTT TTTGCTGAAA GGAGGAACT. The 8 bp spacer sequence in Fig. 4 is TACTAGAG. Plasmids were purified by the alkaline lysis method (HiSpeed kits by Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and insert sequences were confirmed by sequencing.

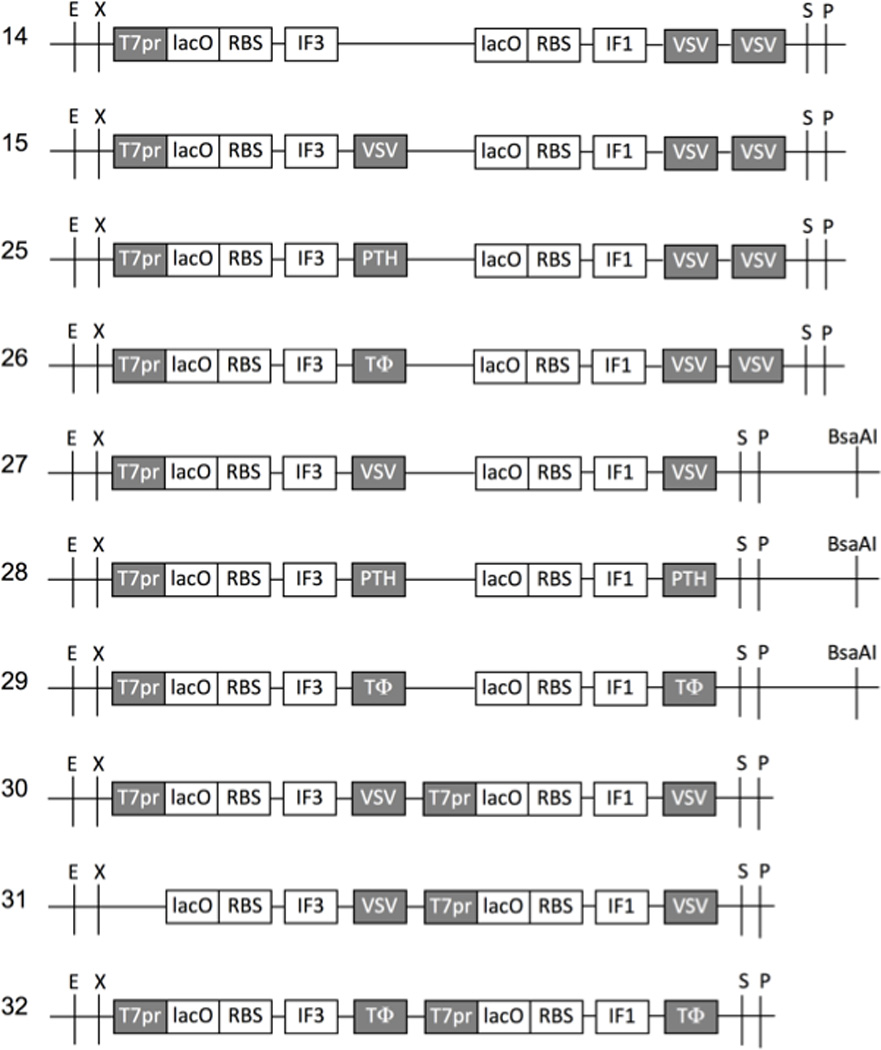

Figure 1.

Plasmid constructs containing dimeric genes. Variable modules are in grey. T7pr: T7 RNAP promoter; lacO: lac operator; RBS: ribosome binding site; IF3 and IF1: genes for E. coli translation initiation factors; VSV, PTH and TΦ: T7 RNAP terminators; E: EcoRI; X: XbaI; S: SpeI; P: PstI.

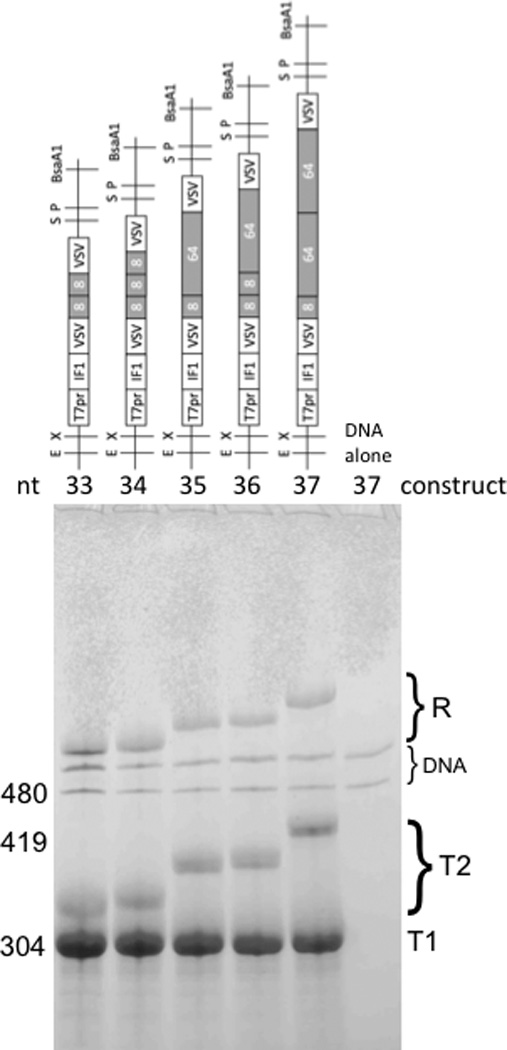

Figure 4.

Monomeric gene constructs and their transcription products. Constructs (top) were designed to determine the effect of spacing on tandem VSV terminator efficiencies. Variable modules are in grey, with sizes in bp given in white. Transcription products of BsaAI-linearized plasmids were analyzed by polyacrylamide/urea gel electrophoresis and staining with toluidine blue (bottom). Marker RNAs (not shown) had the nucleotide sizes and mobilities shown. Faint background bands present in all phenol/chloroform-extracted, ethanol-precipitated, cut plasmids are presumably prominently staining restriction fragments derived from a region outside the inserts and are labeled DNA on the figure; other labels are as in Fig. 3.

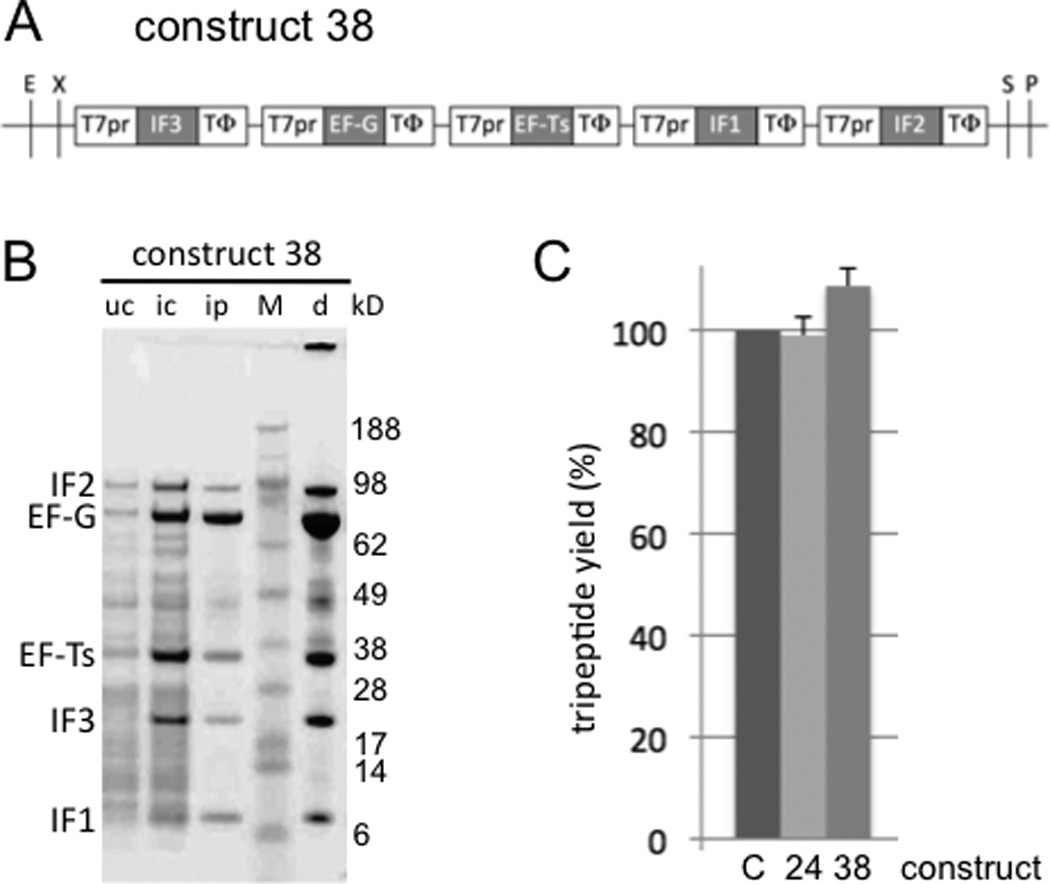

Figure 5.

Coexpression, copurification and translation activity of protein products from pentameric gene constructs. A. Pentameric gene/TΦ construct assembled using the BioBrick strategy. B. In vivo protein coexpression and copurification from construct 38. uc: Uninduced cell crude lysate supernatant; ic: induced cell crude lysate supernatant; ip: induced cell purified proteins from Ni-NTA; M: molecular weight marker proteins; d: dialyzed ip. C. Purifed in vitro translation using the five translation factors produced simutaneously from constructs 24 (Du et al. 2009) or 38 together with one other translation factor, EF-Tu. C: positive control translations using the six individually purified factors, normalized to 100% in each experiment. Standard deviations of the test translations are shown.

Purified transcriptions with T7 RNAP

Plasmid preps (1 µg), either untreated, linearized or treated with E. coli Topoisomerase I according to the manufacturer’s protocol (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), were transcribed in 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM spermidine, 0.05 mg/ml BSA, 20 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.01% Triton-X100, 4 mM each NTP, 0.005 U/µl inorganic pyrophosphatase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1 U/µl rRNasin (Promega, Madison, WI) and 25 U T7 RNAP (New England Biolabs or purified from overexpression of pBH161 plasmid kindly supplied by William McAllister (He et al. 1997)) in 20 µl at 37°C for 3 h (Milligan and Uhlenbeck 1989). Toluidine blue-stained gel bands were quantified by Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gels were reproducible.

Overexpressions in E. coli

Transformed E. coli BL21 (λDE3) cells were grown in LB/kanamycin (50 µg/ml) to OD600 0.6–0.8, IPTG was added to 1 mM, and cells were harvested at 3–5 h. For Figs. 2 and 5B lanes uc and ic, cells were lysed with 8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, centrifuged at 10,000 g and supernatants analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. Gels were reproducible. For Fig. 5B lanes ip and d, cells were lysed under native conditions by sonication, centrifuged and the supernatant purified using Ni-NTA agarose as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA); purified proteins were dialyzed against 100 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4.

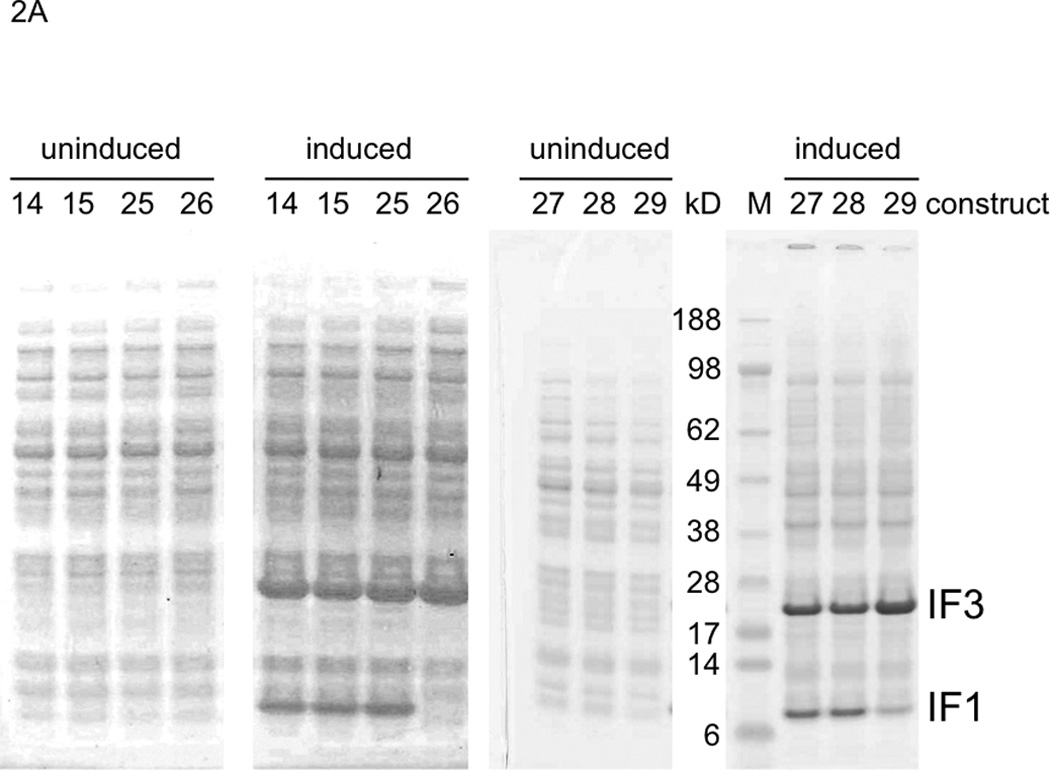

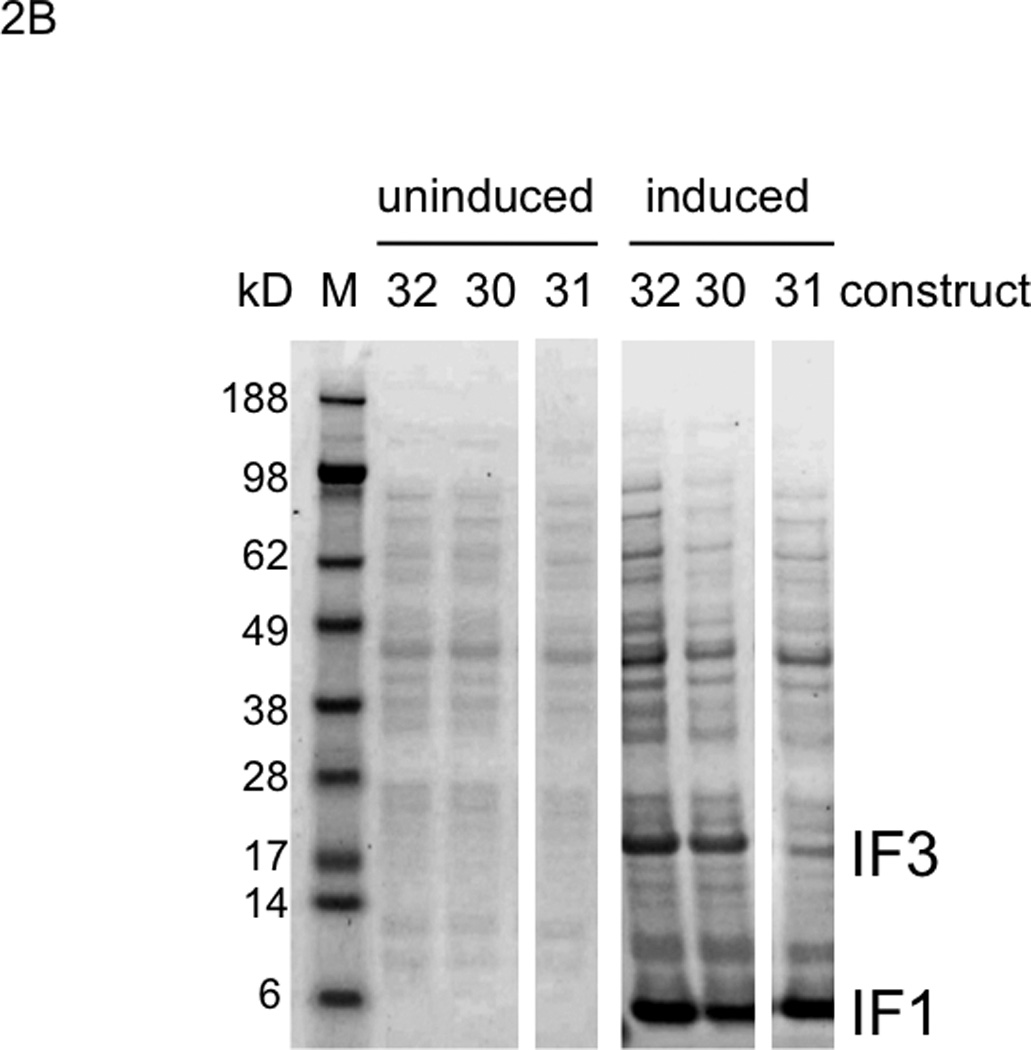

Figure 2.

Protein overexpression in E. coli of all constructs in Fig. 1. A. Overexpression of constructs having a T7pr upstream of the first gene, not the second gene. B. Overexpression of constructs having a T7pr upstream of the second gene. M: molecular weight marker proteins.

Purified translations

To assay translation factors in a translation cycle including translocation, translations were programmed for incorporation of a 3H-amino acid at the C-terminus of a tripeptide. Positive control translations contained 0.5 µM each of individually expressed and purified E. coli IF1, IF2, IF3, EF-G and EF-Ts, 2.5 µM EF-Tu, 0.25 µM purified ribosomes, 1 µM appropriate mRNA, 0.2 µM (limiting) unlabeled fMet-tRNAifMet, 0.5 µM unlabeled first elongator aminoacyl-tRNA and 0.5 µM 3H-labeled C-terminal, elongator aminoacyl-tRNA (Tan et al. 2005). Translations were performed without preincubation in 5 µl volumes at 37°C for 40 min, terminated by the addition of NaOH, then fractionated by ion exchange mini-chromatography. Translations for constructs 24 and 38 used mRNAs encoding fMVE and fMTV, respectively, together with appropriate cognate aminoacyl-tRNAs, and substituted individually expressed IF1, IF2, IF3, EF-G and EF-Ts with batch overexpressed/Ni-NTA-copurified/dialyzed protein products. Maximal concentrations of individual translation factors assayed varied from 0.66–7.2 µM, depending on the relative abundances of the factors in the batches; using three times less of the batches did not significantly affect tripeptide yields.

Results and Discussion

VSV and PTH T7 termination are severely inhibited in vivo

Surprisingly efficient transcription through a VSV terminator was first suggested based on high overexpression in E. coli of the downstream protein from bicistronic constructs of E. coli initiation factor 3 (IF3) and initiation factor 1 (IF1) genes that contained only one T7 RNAP promoter per construct ((Du et al. 2009); e.g. see constructs 14 and 15 shown again here in Fig. 1). In contrast, in vitro transcriptions and translations of these and related uncut, circular plasmids had given decreasing yields of the downstream (IF1) RNA transcript portion and IF1 protein as the number of VSV terminators between the IF3 and IF1 genes increased, as predicted (Du et al. 2009). In order to test our hypothesis that the in vivo results were due to efficient run through of class II transcription termination, we made new dimer constructs that replaced the VSV terminator with the classic class II terminator, PTH, or the classic class I terminator, TΦ (Fig. 1, constructs 25 and 26). Substitution with PTH gave the same overexpression as with the VSV terminator or with no terminator (Fig. 2A, induced 25, 14 and 15; the latter two are repetitions of (Du et al. 2009) as controls; quantitated with replicates in Supplementary Fig. S1). In striking contrast, substitution with TΦ abolished downstream IF1 overexpression (Fig. 2A, induced 26). This indicated very little, if any, class II termination occurs during plasmid transcription in E. coli. These results were confirmed with related constructs 27–29 (Fig. 1; these constructs were prepared for Fig. 3 below) that differed from constructs 15, 25 and 26 only in the number and/or type of terminators located downstream of the downstream gene (Fig. 2A, induced 27–29).

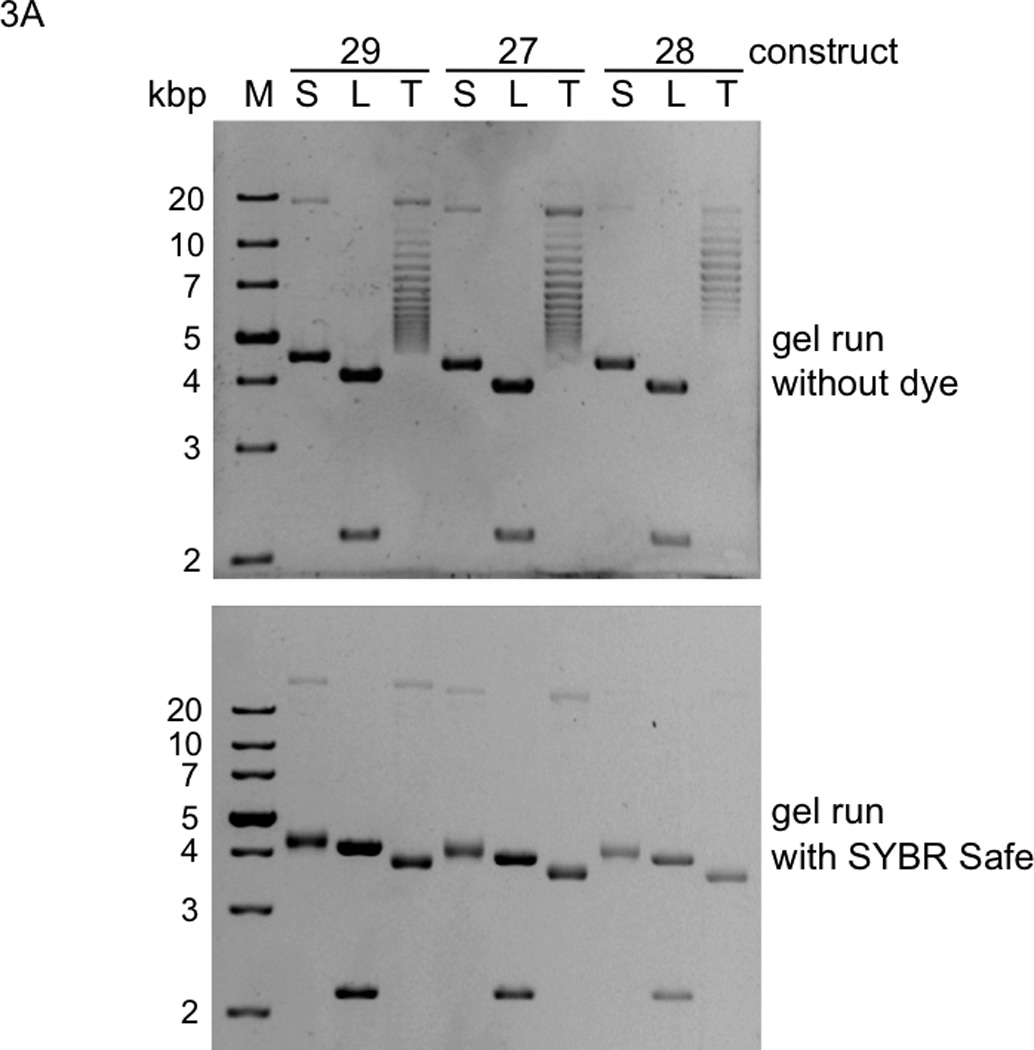

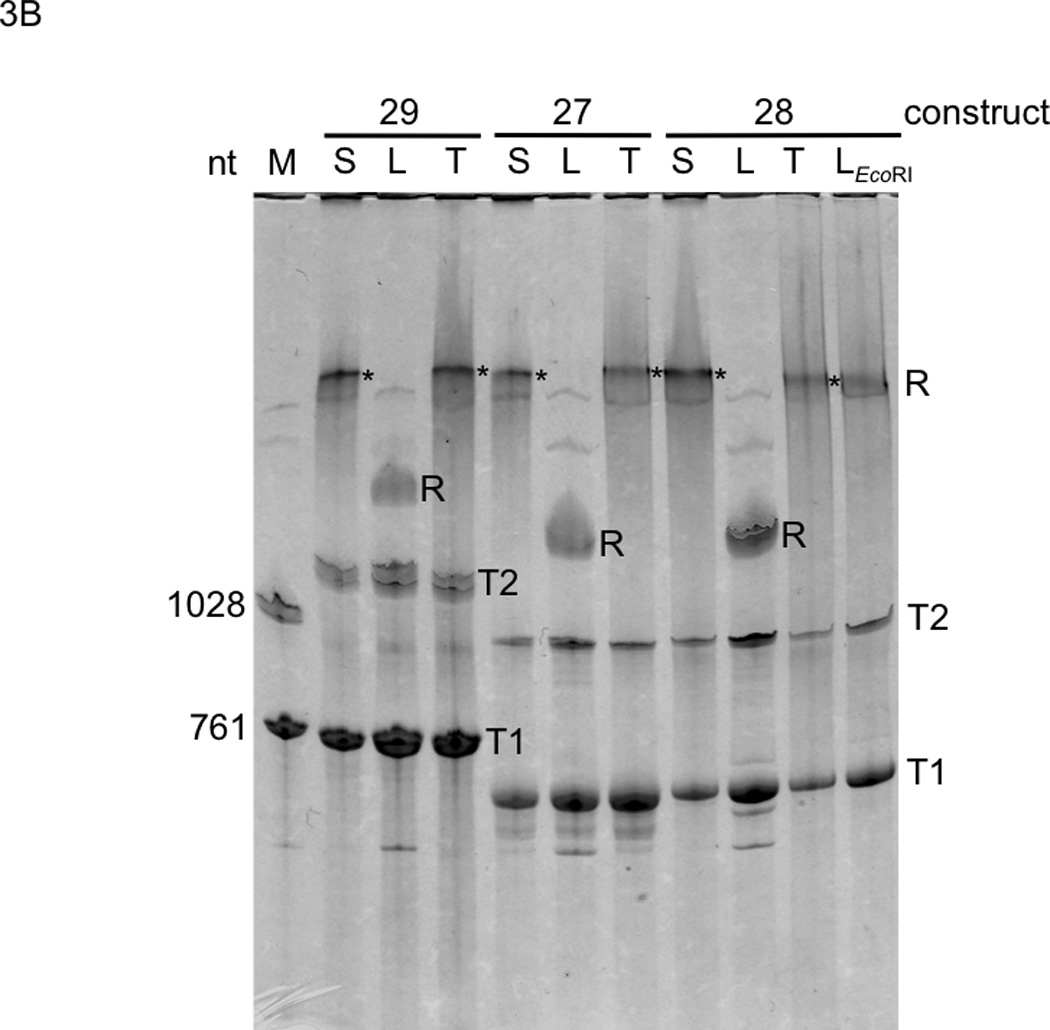

Figure 3.

Analysis of topologies and T7 RNAP transcription products of plasmid constructs 27–29. S: supercoiled plasmid prep; L: linearized plasmid prep (cut at two sites by BsaAI); T: topoisomerase I-treated plasmid prep. A. DNAs were electrophoresed through 0.8% agarose gels and visualized with SYBR Safe (photographic negatives are shown). Note that the in the lower gel, with respect to the DNA markers (M), the supercoiled plasmids ran faster and the topoisomerase-treated plasmids collapsed into a single band. B. Transcription products were electrophoresed through a 3.5% polyacrylamide/urea gel and stained with toluidine blue. M: marker RNAs; T1 and T2: termination products from first and second terminators, respectively; R: run off products; *: products from an efficient stop at a site close to the downstream end of template LEcoRI (construct 28 cut by EcoRI just upstream of the T7pr that yielded a marker run off product corresponding to once around the plasmid).

Additional evidence for inefficient VSV termination in vivo had come from protein overexpression from pentameric gene constructs where each of the five genes was flanked by a T7 promoter and a VSV terminator (Du et al. 2009). Yields of the five different protein products from each construct correlated roughly with the number of upstream T7 promoters, and this relationship held for the two different gene orders tested (constructs 21–24 of (Du et al. 2009)). The presumed explanation was a combination of (i) inefficient VSV terminations and (ii) inefficient transcription completely around the plasmid through the pentameric insert again and/or inefficient translation of such distal downstream, repeated, pentameric, insert RNA copies. If both processes in (ii) were efficient, there would have been similar yields of each protein, regardless of the gene order. Although transcription by T7 RNAP of plasmids lacking T7 terminators is highly processive in vitro and vivo and may frequently go around the plasmid a few times, some plasmid sequences do result in efficient termination at non-standard T7 terminator sites (Studier and Moffatt 1986). To test our hypothesis that in vivo protein production from downstream translation of “go around” transcripts was negligible from our plasmids, we constructed two new variants of our dimeric gene overexpression system: construct 30 with each gene flanked by a T7 promoter and a VSV terminator, and construct 31 that differed by deletion of its upstream T7 promoter (Fig. 1). Thus, if IF3 overexpression occurred from induction with construct 31, it would come from go around T7 RNAP transcription/translation. As expected, control construct 30 gave the same overexpression pattern of IF3 and IF1 (Fig. 2B, induced 30; quantitated with replicates in Supplementary Fig. S1) as previously observed with a highly related construct (construct 11 in (Du et al. 2009) only differed from construct 30 by having one additional VSV terminator downstream of IF1). In marked contrast, deletion of the upstream T7 promoter reduced IF3 production to a barely detectable level (Fig. 2B, induced 31). This supported our hypothesis that go around transcription/translation was minimal from our plasmids, and supported our interpretation of the prior pentameric overexpression results as implying poor termination by VSV terminators in vivo (Du et al. 2009).

Our arbitrary choice here of IF3 as the coding sequence immediately upstream of the terminators is not the reason termination is inefficient in vivo for class II, not class I, termination. In comparison with constructs 14, 15, 25 and 26, constructs 16 and 17 (Du et al. 2009) have additional sequences between a VSV terminator and the upstream IF3 and downstream IF1 genes, yet they give the same in vivo expression patterns. Furthermore, constructs 21 and 22 (Du et al. 2009) have VSV terminators immediately downstream of four different, non-IF3 genes, yet their in vivo expression patterns again indicate inefficient termination.

In an attempt to activate class II termination in vivo, we cotransformed E. coli with pLysS to express T7 lysozyme because this enzyme increases efficiencies of termination in vitro with all class II terminators (Lyakhov et al. 1998). However, based on our in vivo overexpression assay performed as in Fig. 2A (using constructs 14–17 of (Du et al. 2009); results not shown), pLysS did not activate VSV termination in vivo. So for in vivo termination of T7 RNAP, there is no current alternative to classical class I termination. The TΦ strategy is indeed effective for overexpression in vivo in our dimeric monocistronic format, as verified using construct 32 (Fig. 1) in Fig. 2B (induced 32). While its overexpression is not significantly better than from our class II construct 30 (Fig. 2B, induced 30), we reasoned that the class I approach would give more balanced overexpression for pentameric genes (tested below). Another conclusion, given our dramatic differences in results between in vitro and in vivo with VSV and PTH terminators, is that in vitro class II termination data may not be relevant to the in vivo situation (e.g. concerning CJ).

VSV and PTH T7 termination are minimally affected by supercoiling in vitro

Before moving to more complex pentameric gene constructs, we further exploited our simpler dimeric gene constructs to test a potential explanation for our dramatic differences between in vitro and in vivo class II terminations: the published personal communication stating “Mead has found that utilization of the PTH terminator is decreased about 10-fold on a negatively supercoiled template as opposed to a linear template” (He et al. 1998). However, we note that this explanation may only be applicable to PTH, not VSV, because of the published efficient VSV termination in vitro from transcription of unlinearized, circular, presumably supercoiled plasmid DNAs (Whelan et al. 1995). It is nevertheless conceivable that those circular VSV plasmid templates were somehow nicked during preparation and/or storage and therefore actually relaxed. Similarly, our efficient VSV termination in coupled transcription/translations in vitro using circular DNAs (Du et al. 2009) is even more likely to have suffered from a nicking complication, given the known high DNase activities in crude translation systems.

Our experimental approach required (i) verification that our plasmid preparations were supercoiled and (ii) comparison of termination efficiencies from supercoiled and relaxed forms of each plasmid template in a purified transcription system. We used our dimeric gene constructs 27–29 (Fig. 1), as opposed to monomeric constructs, because the second termination per plasmid provides additional comparative data. Analysis of these plasmid preps, together with their linearized and topoisomerase I-relaxed derivatives, by electrophoresis in the absence or presence of interchelating dye verified that the untreated plasmids were indeed supercoiled (Fig. 3A (Bjornsti and Megonigal 1999)). These three topological versions of each template were then transcribed by T7 RNAP and analyzed by electrophoresis. Surprisingly, DNA topology had little, if any, effect on PTH termination (Fig. 3B). VSV and TΦ termination were also similarly unaffected (Fig. 3B). Thus, our VSV terminations are consistent with the published data by (Whelan et al. 1995), while our PTH terminations are inconsistent with the personal communication by Mead cited by (He et al. 1998). If Mead’s results were cited correctly, his PTH termination assay must have been different from ours in some very important way. In any case, our undetectable VSV and PTH termination activity in vivo cannot be attributed to negative supercoiling. Developing a system to study inhibition of class II termination may prove challenging given that inhibition is not observed in purified transcription systems with different extents of supercoiling or even with circular native plasmids in crude translation systems containing all soluble E. coli proteins (Du et al. 2009). Possible causes of the inhibition are highly speculative, ranging all the way from in vivo ionic or substrate concentrations to antitermination proteins. More definitively, we can now conclude that template linearization is unnecessary when using PTH or VSV terminators for in vitro synthetic biology projects.

Efficient termination in vitro of VSV terminators in tandem

Further information relevant to in vitro synthetic biology projects is revealed by comparison of termination efficiencies at the first and second terminators within individual linearized constructs (Fig. 3B, lanes 27L, 28L and 29L). The calculated efficiencies of termination at T1 and T2 from densitometric analysis of replicate gels (Supplementary Fig. S2) gave comparable efficiencies of termination at both terminators within each construct, indicating that a spacer sequence of 336 bp (i.e. the whole IF1 gene) is sufficient for virtually independent function of tandem VSV and PTH terminators. This independence differs somewhat from our prior results with tandem VSV terminators spaced only 8 bp apart, where second and third VSV terminations (12–41%) were less efficient compared with the first (51–62%; (Du et al. 2009)). This raises the question of the minimum spacer sequence required for independent function of VSV terminators, pertinent to our proposal that small terminators, closely spaced in tandem, could be useful in synthetic biology for overcoming the inherent inefficiency of single termination (Forster and Church 2006). This question was addressed by building and transcribing IF1 constructs 33–37 having intermediate spacer lengths (Fig. 4). The calculated efficiencies of termination at T1 and T2 from densitometric analysis of replicate gels (Supplementary Fig. S3) gave the same efficiencies of termination in all cases, even with spacers as short as 16 bp. This demonstrated independent termination at tandem terminators with a high combined efficiency of ~90%. The VSV terminator-16 bp spacer-VSV terminator sequence is only 52 bp long, four times smaller than prior tandem terminator constructs where both terminators were fully active in vitro (tandem TΦ terminators (Baron and Barrett 1997; Macdonald et al. 1993; Wirtz et al. 1998)). As our 52 bp tandem terminator is easier to synthesize from deoxyribonucleotides and less likely to undergo recombination than the larger TΦ dimer, it should constitute a useful part in the synthetic biologist’s toolkit for in vitro applications (Forster and Church 2007). Furthermore, essentially complete termination should be possible if more tandem terminators are inserted.

Coordinated overexpression of five genes using class I terminators in vivo

Next, we returned to our in vivo synthetic biology goal of developing methods for modular construction of pre-designed multigene systems. We tested if the TΦ termination strategy (induced 32 in Fig. 2B), the most promising of the termination strategies based on our results, could be generalized to a more complicated, pentameric, gene overexpression goal. Such a strategy was successful for an octameric gene construct (Watanabe et al. 2006), although it is unclear if all proteins were highly expressed. Our goal is synthesis from a single plasmid of five of the six His-tagged E. coli translation factors required for our simplified translation system (Forster et al. 2001)). The sixth factor, EF-Tu, was omitted because it is required at much higher levels for efficient reconstitution of translation. Despite the recombination potential of up to five repeats of the 120 bp TΦ terminator, the four-step BioBrick cloning of construct 38 (Fig. 5A) in E. coli DH5α cells was straightforward and the constructs were stable. The final construct was also stable during growth and overexpression in E. coli BL21 (λDE3) cells, conditions known to select against unstable (or toxic) plasmids. Comparison of cell lysates of uninduced versus induced cells containing construct 38 revealed induction bands for all five encoded proteins (Fig. 5B, lanes uc and ic). Although the molar yields of the five translation factor products were not identical, this constitutes the only example that we are aware of, in addition to our clones 23 and 24 (Du et al. 2009), of simultaneous overexpression of five proteins efficiently enough to detect all as stained induction bands in crude cell lysates. Expression was leaky in the uninduced control, presumably due to increasing the number of plasmid-encoded lac operators five times without altering the number of plasmid-encoded lac genes (just one).

In contrast to the pentameric gene overexpression strategy without TΦ (Du et al. 2009), the pentameric strategy with TΦ here achieved success with the first clone constructed. Furthermore, it also should be more modular because of the high termination efficiency of TΦ in vivo. The potential disadvantage versus the strategy without TΦ is the higher recombination potential when making constructs containing tens of TΦ terminators (e.g. for our proposed coexpression and copurification of all 31 proteins of the PURE translation system (Shimizu et al. 2001) from one plasmid or genome to dramatically decrease its cost, or for building a minimal cell). However, in preliminary studies we have cloned plasmids containing up to 17 genes with 17 TΦ terminators and these also appear stable in E. coli DH5α cells during growth and overexpression in E. coli BL21 (λDE3) cells (unpublished data). With the advent of many new E. coli strains engineered to decrease recombination, it remains to be seen if the potential recombination disadvantage is imagined or real.

An application of the in vivo multigene overexpression strategy: simplification of translation reconstitution

Utility of our pentameric coexpression/copurification strategies, either with TΦ (construct 38) or without TΦ (construct 24 in (Du et al. 2009)), was demonstrated by reconstitution of translation. Large-scale overexpression from either clone followed by single-batch Ni-NTA binding and elution under native conditions yielded all five proteins in purified form (Fig. 5B, lanes ip and d for construct 38; see Fig. 7B in (Du et al. 2009) for construct 24). Our standard purified system for tripepeptide synthesis was then reconstituted by substituting individually-purified IF1, IF2, IF3, EF-Ts and EF-Tu with the same five factors coexpressed/copurifed from either construct (see Materials and Methods). Tripeptide yields were equivalent, independent of whether the five translation factors were prepared separately (Fig. 5C, bar C) or together (Fig. 5C, bars 24 and 38), demonstrating that the overexpressed proteins function as expected. Thus our coexpression/copurification strategies substantially reduce the time and effort associated with production of our reconstituted translation system. The availability of these new clones makes this reconstituted translation system less expensive and more accessible for basic research (Pavlov et al. 2009) and for synthetic biology applications such as peptidomimetic library synthesis in selections by pure translation display (Forster et al. 2004).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank William McAllister for supplying pBH161 plasmid encoding His-tagged T7 RNA polymerase, William McAllister, Neil Osheroff, Rui Sousa and F. William Studier for discussions of our results, and Måns Ehrenberg, Michael Jewett, Harriet Mellenius and Samudyata Vanamali for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society and Uppsala University.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health

Contract grant sponsor: American Cancer Society

References

- Baron MD, Barrett T. Rescue of rinderpest virus from cloned cDNA. J Virol. 1997;71(2):1265–1271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1265-1271.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsti M-A, Megonigal M. Resolution of DNA molecules by one-dimensional agarose-gel electrophoresis. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1999;94:9–17. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-259-7:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Goldman E. Reversal of inhibition by the T7 concatemer junction sequence on expression from a downstream T7 promoter. Gene Expr. 2001;9(6):257–264. doi: 10.3727/000000001783992524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Gao R, Forster AC. Engineering multigene expression in vitro and in vivo with small terminators for T7 RNA polymerase. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;104(6):1189–1196. doi: 10.1002/bit.22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster AC, Church GM. Towards synthesis of a minimal cell. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2(45):1–10. doi: 10.1038/msb4100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster AC, Church GM. Synthetic biology projects in vitro. Genome Res. 2007;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1101/gr.5776007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster AC, Cornish VW, Blacklow SC. Pure translation display. Anal Biochem. 2004;333(2):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster AC, Weissbach H, Blacklow SC. A simplified reconstitution of mRNA-directed peptide synthesis: activity of the epsilon enhancer and an unnatural amino acid. Anal Biochem. 2001;297(1):60–70. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey B, Korus M, Goldman E. The T7 concatemer junction sequence interferes with expression from a downstream T7 promoter in vivo. Gene Expr. 1999;8(3):141–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Kukarin A, Temiakov D, Chin-Bow ST, Lyakhov DL, Rong M, Durbin RK, McAllister WT. Characterization of an unusual, sequence-specific termination signal for T7 RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(30):18802–18811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Rong M, Lyakhov D, Gartenstein H, Diaz G, Castagna R, McAllister WT, Durbin RK. Rapid mutagenesis and purification of phage RNA polymerases. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;9(1):142–151. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett MC, Forster AC. Update on designing and building minimal cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21(5):697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keasling JD. Manufacturing molecules through metabolic engineering. Science. 2010;330(6009):1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1193990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight T. Indempotent vector design for standard assembly of biobricks. 2003 http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/21168.

- Kwok R. Five hard truths for synthetic biology. Nature. 2010;463(7279):288–290. doi: 10.1038/463288a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyakhov DL, He B, Zhang X, Studier FW, Dunn JJ, McAllister WT. Mutant bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerases with altered termination properties. J Mol Biol. 1997;269(1):28–40. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyakhov DL, He B, Zhang X, Studier FW, Dunn JJ, McAllister WT. Pausing and termination by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1998;280(2):201–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald LE, Durbin RK, Dunn JJ, McAllister WT. Characterization of two types of termination signal for bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1994;238(2):145–158. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald LE, Zhou Y, McAllister WT. Termination and slippage by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1993;232(4):1030–1047. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead DA, Szczesna-Skorupa E, Kemper B. Single-stranded DNA 'blue' T7 promoter plasmids: a versatile tandem promoter system for cloning and protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1986;1(1):67–74. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JF, Uhlenbeck OC. Synthesis of small RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:51–62. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak D, Siller S, Guo Q, Sousa R. Mechanism of T7 RNAP pausing and termination at the T7 concatemer junction: a local change in transcription bubble structure drives a large change in transcription complex architecture. J Mol Biol. 2008;376(2):541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov MY, Watts RE, Tan Z, Cornish VW, Ehrenberg M, Forster AC. Slow peptide bond formation by proline and other N-alkylamino acids in translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(1):50–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809211106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Inoue A, Tomari Y, Suzuki T, Yokogawa T, Nishikawa K, Ueda T. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19(8):751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW, Moffatt BA. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189(1):113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Blacklow SC, Cornish VW, Forster AC. De novo genetic codes and pure translation display. Methods. 2005;36(3):279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Hotta K, Praseuth AP, Koketsu K, Migita A, Boddy CN, Wang CC, Oguri H, Oikawa H. Total biosynthesis of antitumor nonribosomal peptides in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(8):423–428. doi: 10.1038/nchembio803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan SP, Ball LA, Barr JN, Wertz GT. Efficient recovery of infectious vesicular stomatitis virus entirely from cDNA clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(18):8388–8392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz E, Hoek M, Cross GA. Regulated processive transcription of chromatin by T7 RNA polymerase in Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(20):4626–4634. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.20.4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.