Abstract

Antiviral drugs are important components for the control of influenza. The key question is whether antiviral use or natural virus evolution will lead to the emergence of drug-resistant virus with comparable or superior fitness to drug-susceptible counterpart. Currently, neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors (NAIs) are the first choice for influenza prevention and treatment. In this article we will review complex process of the risk assessment for the fitness of NAIs-resistant seasonal H1N1 and H3N2, pandemic 2009 H1N1, and highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A viruses: identification of antiviral susceptibility, degree of functional NA loss, molecular markers of resistance, and evaluation of replicative ability in vivo, virulence and transmissibility in animal studies (mouse, ferret and guinea pig models).

Antiviral drugs currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration to control influenza infection are M2-ion channel blockers (ie, amantadine and rimantadine) and neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors [(NAI), ie, zanamivir and oseltamivir). Both classes of drugs target specific influenza A virus proteins and interfere with either viral uncoating inside the cell (M2-blockers) or the release of influenza virions from infected cell (NAI) [1]. The NAIs are effective against all 9 NA subtypes of influenza A viruses and 2 lineages of influenza B viruses; adamantanes are only effective against influenza A viruses.

The incidence of naturally occurring amantadine-resistant variants has increased dramatically since 2003 and thus limited our options to NAIs. Although NAIs were assumed to be less prone to select resistant influenza viruses, NAI-resistant variants exist [2–4]. Clinically derived drug-resistant viruses have mutations that are NA subtype-specific and differ with the NAI used [5]. The most frequently observed mutations in NAI-resistant variants of influenza A viruses of the N1 NA subtype are H274Y and N294S (N2 numbering here and throughout the text); those of N2 NA subtype most frequently harbor R292K and E119V, and influenza B viruses most frequently harbor R152K and D198N. Although amino acid substitutions at other positions at the catalytic or framework NA residues of influenza A viruses also reduce NAI susceptibility [5], the contribution of these substitutions in clinic is uncertain.

Definition of viral fitness and methods of analysis

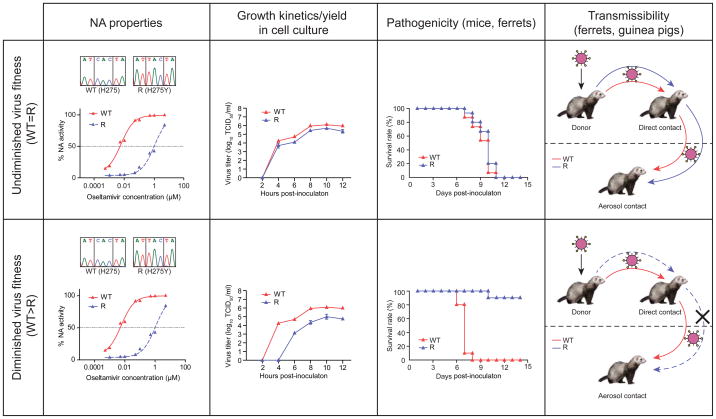

Viral fitness can be defined as the summation of parameters that quantify the degree of virus adaptation to a given environment [6]. Virus replication is an error-prone process resulting in a large number of variants in patients. Misincorporation in the influenza genome occurs at a rate of 10−3 to 10−5 events per nucleotide, suggesting that the emergence of resistant variants is inevitable [7]. However, the fitness of drug-resistant mutants differs and can be separated into 3 groups by comparison to drug-susceptible counterparts: (1) undiminished virus fitness (wild-type (WT)=resistant (R); (2) reduced virus fitness (WT>R); and (3) superior virus fitness (WT<R) (Figure 1). If the resistance mutations led to only a modest biologic fitness cost and the virus remained highly transmissible, then the effectiveness of the antiviral would drop dramatically.

Figure 1. Assessment of fitness of neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza viruses in vitro and in vivo.

NA, neuraminidase; WT, wild-type virus; R, NAI–resistant virus. These figures are just examples of experimental data obtained with WT and R viruses.

WT=R, fitness of the wild-type virus is similar to that of its NAI-resistant counterpart; WT>R, fitness of the wild-type virus is greater than that of its NAI-resistant counterpart, data representing superior fitness of NAI-resistant counterpart as compared to wild-type virus (WT<R) is not included into the figure.

Determination of the virus resistance phenotype should be based on both phenotypic and genotypic methods. Phenotypic methods include biochemical NA inhibition assays using different substrates [8–10]. Plaque reduction assays (or virus yield reduction assays) are not recommended for evaluating NAI resistance, particularly that of low-passage clinical isolates, because these assays may yield anomalous results. Such faulty results can occur because the viral hemagglutinin (HA) from clinical isolates prefers to bind to α-2,6-linked sialic acid receptors rather than to those expressed on the surface of the cells, eg, on Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Genotypic methods involve screening for known NAI mutations in a viral genome and include Sanger DNA sequencing, pyrosequencing method, single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assays, and real-time PCR approaches [11–14]. All methods except Sanger sequencing are NA subtype–specific and should be developed and validated for each known amino acid substitution conferring resistance to NAIs. SNP assays enable detection and quantification of a minor subpopulation of NAI-resistant and -susceptible mutants [12].

The fitness of NAI-resistant mutants can be experimentally assayed in vitro by determining NA enzyme kinetics [ie, the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km)], which reflect the affinity of NA for its substrate, and velocity (Vm), which reflects NA activity [15–17]. HA-receptor binding assays, plaque morphology, and replication kinetics in different cell cultures can also be measured.

In vivo measurements of the pathogenicity and transmissibility of NAI-resistant mutants make use of 3 animal models: BALB/c mice, Hartley strain guinea pigs, and ferrets [18–20]. The mouse model is limited because mice are not natural hosts for influenza, do not show signs of infection similar to those seen in humans, and do not transmit virus [18]. Hartley strain of guinea pig has been reported to be a transmission model for human influenza viruses although the lack of clinical signs of infection limit its usefulness for evaluating pathogenicity [19]. Ferrets are the gold standard in animal models for influenza pathogenicity and transmissibility because they have human-like distribution of sialic-acid receptors in their respiratory tracts, show clinical signs of infection similar to those seen in humans (ie, fever, sneezing, coughing), and are susceptible to contact and aerosol routes of influenza transmission [18, 20, 21].

Fitness of oseltamivir-resistant seasonal H1N1 and H3N2 influenza viruses

Among known NAIs resistance markers, the H274Y is one of the best characterized. Compared to oseltamivir-susceptible viruses, seasonal H1N1 viruses with the H274Y substitution were thought to have high levels of oseltamivir resistance and reduced growth in cell culture, attenuated phenotypes in mice and ferrets, and poor transmissibility in animals [22–24]. These findings led to the hypothesis that NAI-resistant viruses would be less infectious, less transmissible in humans, and thus unlikely to be of clinical consequence. This hypothesis held true for 8 influenza seasons after NAIs became available in clinics in 1999, and the prevalence rate of oseltamivir-resistant viruses was less than 1% in adults and 4% to 18% in children [25, 26]. However, beginning in the 2007–2008 influenza season, viruses containing the H274Y NA mutation rapidly became predominant among human seasonal H1N1 isolates [2].

The unexpected natural emergence (ie, in the absence of drug pressure) and spread of oseltamivir-resistant variants among seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses of A/Brisbane/59/2007 lineage showed that drug-resistant viruses can be extremely fit and transmissible in humans [4, 27]. Experimental studies confirmed the undiminished fitness of oseltamivir-resistant A/Brisbane/59/2007-like viruses that could replicate to titers similar to or greater than those of their oseltamivir-susceptible counterparts and cause a higher febrile response in ferrets (Table 1) [28]. Moreover, these viruses’ NA had an increased affinity for its substrate, leading to restoration of NA receptor-cleaving functions to balance the HA receptor-binding functions [16]. The functional balance of NA and HA can also be restored through the acquisition of “permissive” secondary mutations outside the NA active site that enhance NA’s surface expression and enable the virus to tolerate subsequent occurrences of the H274Y mutation [29]. The V234M and R222Q NA mutations increase the amount of NA that reaches the cell surface and thus decrease defects in NA folding or transport that are caused by the H274Y mutation [29].

Table 1.

Fitness of clinically derived neuraminidase inhibitor–resistant influenza viruses in experimental models.

| Influenza virus | NA mutation* | NAI susceptibility

|

Virus fitness

|

Overall fitness | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oseltamivir (fold difference) | Zanamivir | In vitro

|

In vivo

|

|||||||

| Growth kinetic | Animal model | Pathogenicity | Direct transmission | Aerosol transmission | ||||||

| Seasonal H1N1 | ||||||||||

| A/Brisbane/59/2007-like | H274Y | R (~770)** | S | WT=R | Ferrets | R>WT | ND | ND | Undiminished | 23 |

| A/Quebec/15349/2008) | ||||||||||

| A/New Caledonia/20/99-like | R (~400–950) | S | WT>R | |||||||

| A/Texas/36/91 | Mice | WT>R | NT | NT | Diminished | 22 | ||||

| rg A/WSN/33 | Ferrets | WT>R | WT>R | ND | Diminished | 22–24 | ||||

| A/Mississipi/3/2001 | ||||||||||

| A/New Caledonia/20/99 | ||||||||||

| A/Solomon Islands/03/2006 | ||||||||||

| Seasonal H3N2 | ||||||||||

| A/Wuhan/359/95-like | E119V | R (~140–2058) | S | WT=R | Ferrets | ND | WT=R | ND | Undiminished | 24, 30 |

| rg A/Wuhan/359/95 | ||||||||||

| rg A/Panama/2007/99 | Guinea pigs | WT=R | WT=R | WT>R | Diminished | 33 | ||||

| A/California/7/2004-like | E119V+I222V | R (~224–2300) | S | WT=R | Guinea pigs | WT=R | WT=R | WT>R | Diminished | 33 |

| rg A/Panama/2007/99 | ||||||||||

| rg A/Wuhan/359/95 | R292K | R (~10000–38000) | IR (~13) | WT>R | Mice | WT>R | ND | ND | Diminished | 31 |

| A/Sydney/5/97 | ||||||||||

| Ferrets | WT>R | WT>R | WT>R | Diminished | 31, 30, 34 | |||||

| Pandemic 2009 H1N1 | ||||||||||

| rg A/California/04/2009 | H274Y | R (~100–1500) | S | WT≥R | Guinea pigs | ND | WT=R | WT=R | Undiminished | 44 |

| rg A/Hansa Hamburg/01/2009 | ||||||||||

| A/Quebec/147365/2009 | Mice | WT≤R | ND | ND | Undiminished | 45, 47 | ||||

| A/Bethesda/NIH107-D31/2009 | ||||||||||

| A/Bethesda/NIH106-D14/2009 | ||||||||||

| A/Osaka/180/2009 | Ferrets | WT=R | WT=R | WT=R | Undiminished | 44, 46, 47 | ||||

| A/Vietnam/HN32060/2009 | ||||||||||

| A/Denmark/528/2009 | H274Y | R (~200) | S | WT>R | Ferrets | WT=R | WT=R | WT>R | Diminished | 15, 48 |

Amino acid numbering is based on that of N2 NA.

Assayed by performing NA enzyme inhibition assays with MUNANA substrate. The fold difference in enzymatic activity of each mutant was compared to that of its oseltamivir-susceptible counterpart.

Abbreviations: rg, recombinant influenza virus; WT, wild-type virus; R, neuraminidase inhibitor–resistant virus; S, neuraminidase inhibitor–susceptible virus; ND, not determined; IR, intermediate resistance.

WT>R, fitness of the wild-type virus is greater than that of its oseltamivir-resistant counterpart; WT=R, fitness of the wild-type virus is similar to that of its oseltamivir-resistant counterpart; WT<R, fitness of the wild-type virus is less than that of its oseltamivir-resistant counterpart.

Several studies in animal models have examined the infectivity and transmissibility of NAI-resistant H3N2 influenza viruses with the E119V and R292K mutations (Table 1). The E119V mutation confers resistance to oseltamivir, and the R292K mutation confers resistance to oseltamivir and a low resistance to zanamivir [24, 30–34]. In the earliest studies, oseltamivir-resistant H3N2 viruses with the R292K mutation exhibited severely diminished replication and virulence in vitro and in vivo [30, 34] and were therefore thought to be of little clinical consequence. Subsequent studies showed that NAIs-resistant H3N2 viruses may differ substantially in fitness and transmissibility depending on the location of the mutation and the amount of function lost [31]. However, NAI- resistant H3N2 viruses with the R292K mutation are not transmitted among ferrets by direct contact, and those with the E119V mutation must be given at a higher virus dose than the wild-type virus to be transmitted by direct contact [24, 30]. Furthermore, recombinant NAI-resistant H3N2 viruses with either the E119V mutation or the E119V+I222V NA mutations are efficiently transmitted among guinea pigs by direct contact but not by respiratory droplets [32, 33, 35].

Fitness of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza viruses

In April 2009, widely spread oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 A/Brisbane/59/2007–like influenza viruses were replaced by the antigenically divergent, oseltamivir-susceptible H1N1virus that caused the first pandemic of the 21st century [36]. The clinical use of oseltamivir to control influenza increased substantially during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Importantly, most influenza viruses isolated during the pandemic were susceptible to oseltamivir and zanamivir [37]. Sporadic cases of pandemic H1N1 influenza have been associated with mutant viruses possessing the H274Y NA mutation, and more than 200 oseltamivir-resistant variants have been isolated worldwide from patients receiving oseltamivir [38], 76% of whom were immunocompromised [39]. Only a few community clusters of person-to-person transmission of oseltamivir-resistant viruses were reported [40, 41], including 2 suspected cases of nosocomial transmission among immunocompromised patients [42, 43].

To better assess the risk of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic viruses, several groups studied the in vitro properties, pathogenicity, and transmissibility of oseltamivir-susceptible and –resistant viruses (Table 1). Compared to the in vitro growth kinetics of the wild-type virus, the growth of viruses with the H274Y NA mutation was either similar [44] or mildly attenuated 6 to 24 hours after inoculation, although final virus yields of both viruses were similar 48–72 hours after inoculation [15, 45–47]. The H274Y NA mutation reduced NA’s affinity for substrate and its catalytic activity, yet the function of NA in oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 pandemic viruses was not severely impaired [15]. Surprisingly, 4 groups using ferret and guinea pig models found that the transmission rates of oseltamivir-susceptible and -resistant 2009 H1N1 viruses are the same [44–47].

As with other influenza virus subtypes, the observed transmissibility of pandemic oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 viruses depends on the strain and experimental conditions. Duan et al. [15] showed that A/Denmark/528/09 (H1N1) virus with the H274Y NA mutation is less transmissible in ferrets through the respiratory droplet route than is its susceptible counterpart although it is efficiently transmitted through direct contact. The results of competitive fitness experiments in which ferrets were co-inoculated with oseltamivir-susceptible and -resistant viruses confirmed that the fitness of the mutant virus was diminished [48]. However, mutant and wild-type viruses replicated to similar levels in the upper respiratory tract and caused similar clinical signs in inoculated ferrets and thus possessed similar pathogenicity [48]. These data are consistent with the available epidemiological information which showed no evidence of predominant circulation of oseltamivir-resistant viruses [49]. Recently, NA mutations, which confer intermediate level of resistance to oseltamivir and/or zanamivir (S274N; I222R/N/V) were described [37, 50, 51]. Further studies are needed to assess effects of these mutations along and in conjunction with the H274Y NA on fitness of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic viruses.

Fitness of oseltamivir-resistant highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza viruses

The pandemic potential of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza viruses has been a serious public health concern since its first isolation from humans in 1997 [52, 53]. Phenotypic assays of H5N1 influenza viruses isolated from untreated patients revealed high susceptibility to the NAIs oseltamivir and zanamivir [54]. Oseltamivir-resistant variants with the H274Y NA mutation were isolated from 5 patients after [55–57] or before drug treatment [57, 58] out of 562 confirmed human H5N1 cases. Additionally, oseltamivir-resistant H5N1 viruses with the N294S NA mutation were isolated from 2 patients after oseltamivir treatment [57].

Reports about the fitness of highly pathogenic oseltamivir-resistant H5N1 viruses of clade 1 offered different findings [17, 56]. The inefficient transmissibility of H5N1 influenza viruses in ferrets [18] (as in humans) restricted experimental possibilities to evaluations of NA enzymatic properties, replication in cell culture, and pathogenicity in mammals (Table 2). In ferrets, an oseltamivir-resistant A/Hanoi/30408/2005 (H5N1) virus carrying the H274Y NA mutation replicated approximately 10 times less efficiently in the upper respiratory tract than did the wild-type virus [56]. A clone of this mutant H5N1 virus with the N294S substitution also had lower levels of virus replication and pathogenicity in mice and ferrets and less susceptibility to oseltamivir than did the wild-type virus [59]. In contrast, neither the H274Y nor the N294S NA mutations compromised the lethality or pathogenicity of clade 1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) virus in mice and ferrets [7, 60, 61], suggesting that oseltamivir-resistant variants of H5N1 subtype may possess an undiminished phenotype and exhibit high pathogenicity in mammalian species. Interestingly, oseltamivir resistance mutations substantially decrease the enzymatic activity of avian-like NA glycoprotein of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) virus but do not affect virus pathogenicity in mice and ferrets [7, 60]. Thus, the extremely efficient replication complexes of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses can overcome deficiency in NA function, leading to fitness similar to that of wild-type viruses.

Table 2.

Fitness of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses carrying H274Y and N294S NA mutations.

| H5N1 influenza virus | NA mutation* | NA enzyme activity | NAI susceptibility

|

Virus fitness

|

Overall Fitness | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oseltamivir (fold difference) | Zanamivir | In vitro

|

Pathogenicity in vivo

|

|||||||

| Plaque size | Growth kinetic | Mice | Ferrets | |||||||

| rgA/Vietnam/1203/2004 (clade 1) | H274Y | WT>R | R (1500–3000)** | S | WT>R | WT=R | WT=R | WT=R | Undiminished | 17, 59–61 |

| N294S | WT>R | IR (20) | S | WT=R | WT=R | WT=R | WT=R | Undiminished | 17, 59, 61 | |

| A/Hanoi/30408/2005 (clade 1) | H274Y | ND | R (~1500) | S | ND | ND | WT>R | WT>R | Diminished | 56, 63 |

| N294S | ND | R (~15) | S | ND | ND | WT>R | WT>R | Diminished | 63 | |

| rgA/Turkey/15/2006 (clade 2.2) | H274Y | WT>R | R (~1000) | S | WT>R | WT=R | ND | WT>R | Slightly diminished | 60, 62 |

| N294S | WT>R | R (60) | S | WT>R | W=>R | ND | WT<R | Superior | 62 | |

Amino acid numbering is based on that of N2 NA.

Assayed by performing NA enzyme inhibition assays with MUNANA substrate. The fold difference in enzymatic activity of each mutant was compared to that of its oseltamivir-susceptible counterpart.

Abbreviations: rg, recombinant influenza virus; WT, wild-type virus; R, neuraminidase inhibitor–resistant virus; S, neuraminidase inhibitor–susceptible virus; ND, not determined; IR, intermediate resistance.

WT>R, fitness of the wild-type virus is greater than that of its oseltamivir-resistant counterpart; WT=R, fitness of the wild-type virus is similar to that of its oseltamivir-resistant counterpart; WT<R, fitness of the wild-type virus is less than that of its oseltamivir-resistant counterpart.

The background NA sequence of an H5N1 virus can determine whether a particular resistance-associated NA mutation changes the mutant’s fitness. For example, the H274Y NA mutation does not affect the fitness of the A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) virus [30, 60] but diminishes that of the less pathogenic A/Hanoi/30408/2005 (H5N1) virus [56]. Fitness of highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses depend on location of particular NA mutations: in the homogeneous background of clade 2.2 A/Turkey/15/2006 (H5N1)-like virus, the H274Y NA mutation did not affect virulence, and the N294S NA mutation caused significantly higher virus titers and inflammation in the lungs than the wild-type virus did [62].

Concluding remarks

Prior to 2007, the resistance to NAIs among circulating influenza viruses remained low and was though of less clinical significance due to the mutations in the NA that diminished viral fitness of NAIs-resistant mutants. The emergence and spread around the globe of oseltamivir-resistant seasonal H1N1 viruses without drug selective pressure suggested that mutations accumulated through natural genetic drift in influenza viruses can compensate for the fitness deficit in drug-resistant viruses, providing the ability to transmit between individuals. Given the diversity and rapid mutation rate of influenza, understanding the genetic pathways crucial to the emergence of transmissible drug-resistant viruses is a key step in assessing the risk of a drug-resistant, pandemic influenza strain emerging in the future.

Efforts should be made to optimize assays between different laboratories, such as the use of genetically characterized pairs of NAI-susceptible and –resistant viruses, use of recommended cell lines, and improvements in animal models. For example, the virus dose used for inoculation, size of viral particles, direction of air flow, use of both direct contact and aerosol routes of transmission, and time and duration of contact that naive animals have with infected donor animals should be standardized. Furthermore, using the powerful reverse genetics method can provide additional information about the role of mutations from other genes (eg, NP, PB2, and PB1-F2) in drug-resistant viruses. Sensitive methods that enable detection of low abundance viral quasi species can detect resistance in an individual, which may help predict the emergence of clinically important resistant viruses. The risk of emergence of drug-resistant influenza viruses with sufficient viral fitness to become dominant should be monitored closely and considered in seasonal evaluation of circulating viruses.

Neuraminidase inhibitors are important class of antiviral drugs for the control of influenza.

The development of drug resistance is a major obstacle to antiviral therapy.

In this review we focused on the complex process of fitness evaluation for drug-resistant influenza A viruses.

The risk assessments for the emergence of virulent and transmissible drug-resistant influenza viruses are also discussed.

Acknowledgments

The author’s laboratory is funded in part by the National Institute Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, under contract number HHSN266200700005C and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). We thank Julie Groff for making the illustration and Cherise Guess for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1**.Das K, Aramini JM, Ma LC, Krug RM, Arnold E. Structures of influenza A proteins and insights into antiviral drug targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:530–538. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1779. A comprehensive analysis of the crystal structures of influenza A virus proteins and a description of the mechanisms of action of currently available anti-influenza drugs are given together with allosteric explanations of the drug-resistance mechanisms. Protein structure-based discovery approaches for novel anti-influenza drugs are discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meijer A, Lackenby A, Hungnes O, Lina B, van-der-Werf S, Schweiger B, Opp M, Paget J, van-de-Kassteele J, Hay A, Zambon M. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus A (H1H1), Europe, 2007–08 season. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:552–560. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.081280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deyde VM, Xu X, Bright RA, Shaw M, Smith CB, Zhang Y, Shu Y, Gubareva LV, Cox NJ, Klimov AI. Surveillance of resistance to adamantanes among influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) viruses isolated worldwide. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:249–257. doi: 10.1086/518936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharan NJ, Gubareva LV, Meyer JJ, Okomo-Adhiambo M, McClinton RC, Marshall SA, St George K, Epperson S, Brammer L, Klimov AI, et al. Infections with oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) virus in the United States. JAMA. 2009;301:1034–1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferraris O, Lina B. Mutations of neuraminidase implicated in neuraminidase inhibitors resistance. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domingo E, Menendez-Arias L, Holland JJ. RNA virus fitness. Rev Med Virol. 1997;7:87–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(199707)7:2<87::aid-rmv188>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drake JW. Rates of spontaneous mutation among RNA viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4171–4175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wetherall NT, Trivedi T, Zeller J, Hodges-Savola C, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Zambon M, Hayden FG. Evaluation of neuraminidase enzyme assays using different substrates to measure susceptibility of influenza virus clinical isolates to neuraminidase inhibitors: Report of the neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility network. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:742–750. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.742-750.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blick TJ, Tiong T, Sahasrabudhe A, Varghese JN, Colman PM, Hart GJ, Bethell RC, McKimm-Breschkin JL. Generation and characterization of an influenza virus neuraminidase variant with decreased sensitivity to the neuraminidase-specific inhibitor 4-guanidino-Neu5Ac2en. Virology. 1995;214:475–484. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gubareva LV, Webster RG, Hayden FG. Detection of influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors by an enzyme inhibition assay. Antiviral Res. 2002;53:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obenauer JC, Denson J, Mehta PK, Su X, Mukatira S, Finkelstein DB, Xu X, Wang J, Ma J, Fan Y, et al. Large-scale sequence analysis of avian influenza isolates. Science. 2006;311:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1121586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan S, Boltz DA, Li J, Oshansky CM, Marjuki H, Barman S, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. A novel genotyping and quantitative analysis of neuraminidase inhibitor-resistance associated mutations in influenza A viruses by single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00316–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Sheu TG, Wallis TR, Fry A, Dharan N, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. Pyrosequencing as a tool to detect molecular markers of resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors in seasonal influenza A viruses. Antiviral Res. 2009;81:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki Y, Saito R, Sato I, Zaraket H, Nishikawa M, Tamura T, Dapat C, Caperig-Dapat I, Baranovich T, Suzuki T, et al. Identification of oseltamivir resistance among pandemic and seasonal influenza A (H1N1) viruses by an His275Tyr genotyping assay using the cycling probe method. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:125–130. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01401-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Duan S, Boltz DA, Seiler P, Li J, Bragstad K, Nielsen LP, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza virus possesses lower transmissibility and fitness in ferrets. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001022. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001022. Among the studies that evaluated the viral fitness of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 influenza viruses, only the results of this one are in line with epidemiologic and clinical observations and suggest the diminished fitness of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 influenza viruses. This study highlights the importance of combining data from in vitro growth kinetics experiments and data from in vivo direct- and aerosol-contact transmission experiments to determine viral fitness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rameix-Welti MA, Enouf V, Cuvelier F, Jeannin P, van der Werf S. Enzymatic properties of the neuraminidase of seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses provide insights for the emergence of natural resistance to oseltamivir. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000103. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen HL, Ilyushina NA, Salomon R, Hoffmann E, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant recombinant A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) influenza viruses retain their replication efficiency and pathogenicity in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 2007;81:12418–12426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01067-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belser JA, Szretter KJ, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Use of animal models to understand the pandemic potential of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2009;73:55–97. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(09)73002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. The guinea pig as a transmission model for human influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9988–9992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604157103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell CD, Subbarao K. The contribution of animal models to the understanding of the host range and virulence of influenza A viruses. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:502–15. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuoka Y, Lamirande EW, Subbarao K. The ferret model for influenza. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2009;Chapter 15(Unit 15G.2) doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc15g02s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ives JA, Carr JA, Mendel DB, Tai CY, Lambkin R, Kelly L, Oxford JS, Hayden FG, Roberts NA. The H274Y mutation in the influenza A/H1N1 neuraminidase active site following oseltamivir phosphate treatment leave virus severely compromised both in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2002;55:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baz M, Abed Y, Simon P, Hamelin ME, Boivin G. Effect of the neuraminidase mutation H274Y conferring resistance to oseltamivir on the replicative capacity and virulence of old and recent human influenza A(H1N1) viruses. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:740–5. doi: 10.1086/650464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herlocher ML, Truscon R, Elias S, Yen HL, Roberts NA, Ohmit SE, Monto AS. Influenza viruses resistant to the antiviral drug oseltamivir: Transmission studies in ferrets. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1627–1630. doi: 10.1086/424572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheu TG, Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten RJ, Xu X, Bright RA, Butler EN, Wallis TR, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. Surveillance for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among human influenza A and B viruses circulating worldwide from 2004 to 2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3284–3292. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00555-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiso M, Mitamura K, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Shiraishi K, Kawakami C, Kimura K, Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Kawaoka Y. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: Descriptive study. Lancet. 2004;364:759–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16934-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lackenby A, Hungnes O, Dudman SG, Meijer A, Paget WJ, Hay AJ, Zambon MC. Emergence of resistance to oseltamivir among influenza A(H1N1) viruses in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2008:13. doi: 10.2807/ese.13.05.08026-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baz M, Abed Y, Simon P, Hamelin ME, Boivin G. Effect of the neuraminidase mutation H274Y conferring resistance to oseltamivir on the replicative capacity and virulence of old and recent human influenza A(H1N1) viruses. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:740–5. doi: 10.1086/650464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Bloom JD, Gong LI, Baltimore D. Permissive secondary mutations enable the evolution of influenza oseltamivir resistance. Science. 2010;328:1272–5. 328. doi: 10.1126/science.1187816. The authors demonstrated that the H274Y NA mutation decreases the amount of NA on the cell surface and that secondary NA mutations (ie, V234M and R222Q) can compensate for the reduced fitness of the oseltamivir resistance phenotype, showing that the long-term evolutionary potential of NA inhibitor–resistant viruses might depend on “permissive” NA mutations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yen HL, Herlocher LM, Hoffmann E, Matrosovich MN, Monto AS, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza viruses may differ substantially in fitness and transmissibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4075–4084. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4075-4084.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr J, Ives J, Kelly L, Lambkin R, Oxford J, Mendel D, Tai L, Roberts N. Influenza virus carrying neuraminidase with reduced sensitivity to oseltamivir carboxylate has altered properties in vitro and is compromised for infectivity and replicative ability in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2002;54:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon P, Holder BP, Bouhy X, Abed Y, Beauchemin CA, Boivin G. The I222V neuraminidase mutation has a compensatory role in replication of an oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus A/H3N2 E119V mutant. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:715–717. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01732-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouvier NM, Lowen AC, Palese P. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A viruses are transmitted efficiently among guinea pigs by direct contact but not by aerosol. J Virol. 2008;82:10052–10058. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01226-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herlocher ML, Carr J, Ives J, Elias S, Truscon R, Roberts N, Monto AS. Influenza virus carrying an R292K mutation in the neuraminidase gene is not transmitted in ferrets. Antiviral Res. 2002;54:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baz M, Abed Y, McDonald J, Boivin G. Characterization of multidrug-resistant influenza A/H3N2 viruses shed during 1 year by an immunocompromised child. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1555–1561. doi: 10.1086/508777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, Gubareva LV, Xu X, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A(H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gubareva LV, Trujillo AA, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Mishin VP, Deyde VM, Sleeman K, Nguyen HT, Sheu TG, Garten RJ, Shaw MW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus drug susceptibility in vitro. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:1151–1159. doi: 10.3851/IMP1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baz M, Abed Y, Papenburg J, Bouhy X, Hamelin ME, Boivin G. Emergence of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1 virus during prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2296–2297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graitcer SB, Gubareva L, Kamimoto L, Doshi S, Vandermeer M, Louie J, Waters C, Moore Z, Sleeman K, Okomo-Adhiambo M, et al. Characteristics of patients with oseltamivir-resistant pandemic (H1N1) 2009, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:255–257. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.101724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Le QM, Wertheim HF, Tran ND, van Doorn HR, Nguyen TH, Horby P. A community cluster of oseltamivir-resistant cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:86–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910448. This is the first report of community transmission of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus, showing that these viruses can occur in patients who have not received antiviral prophylaxis or treatment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis-North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gulland A. First cases of spread of oseltamivir resistant swine flu between patients are reported in Wales. BMJ. 2009;339:b4975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen LF, Dailey NJ, Rao AK, Fleischauer AT, Greenwald I, Deyde VM, Moore ZS, Anderson DJ, Duffy J, Gubareva LV, et al. Cluster of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus infections on a hospital ward among immunocompromised patients-North Carolina, 2009. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:838–46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seibert CW, Kaminski M, Philipp J, Rubbenstroth D, Albrecht RA, Schwalm F, Stertz S, Medina RA, Kochs G, García-Sastre A, et al. Oseltamivir-resistant variants of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza a virus are not attenuated in the guinea pig and ferret transmission models. J Virol. 2010;84:11219–11226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01424-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamelin ME, Baz M, Abed Y, Couture C, Joubert P, Beaulieu E, Bellerose N, Plante M, Mallett C, Schumer G, et al. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic A/H1N1 virus is as virulent as its wild-type counterpart in mice and ferrets. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001015. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Memoli MJ, Davis AS, Proudfoot K, Chertow DS, Hrabal RJ, Bristol T, Taubenberger JK. Multidrug-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) viruses maintain fitness and transmissibility in ferrets. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:348–57. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiso M, Shinya K, Shimojima M, Takano R, Takahashi K, Katsura H, Kakugawa S, Le MT, Yamashita M, Furuta Y, et al. Characterization of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001079. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duan S, Boltz DA, Seiler P, Li J, Bragstad K, Nielsen LP, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Competitive transmissibility and fitness of oseltamivirsensitive and resistant pandemic influenza H1N1 viruses in ferrets. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2011;5 (Suppl 1):79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO. [Accessed 7 August 2011];Weekly update on oseltamivir resistance to influenza A (H1N1) 2009 viruses. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/oseltamivirresistant20100820.pdf.

- 50*.Hurt A, Lee R, Leang S, Cui L, Deng Y, Phuah S, Caldwell N, Freeman K, Komadina N, Smith D, et al. Increased detection in Australia and Singapore of a novel influenza A(H1N1) 2009 variant with reduced oseltamivir and zanamivir sensitivity due to a S247N neuraminidase mutation. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:19884. Starting in December 2010, an increasing proportion of influenza A (H1N1) viruses with intermediate resistance to both oseltamivir and zanamivir was detected during active surveillance in the Asia-Pacific region. Those mutants possessed a single S247N NA mutation and were widely distributed, suggesting that the mutation does not compromise viral transmissibility. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meijer A, Jonges M, Abbink F, Ang W, van Beek J, Beersma M, Bloembergen P, Boucher C, Claas E, Donker G, et al. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 influenza viruses detected through enhanced surveillance in the Netherlands, 2009–2010. Antiviral Res. 2011 Jul 15; doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.07.004. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Claas EC, Osterhaus AD, van Beek R, De Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Senne DA, Krauss S, Shortridge KF, Webster RG. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351:472–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, Regnery H, Lim W, Hall H, Perdue M, Swayne D, Bender C, Huang J, et al. Characterization of an avian influenza A(H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science. 1998;279:393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hurt AC, Selleck P, Komadina N, Shaw R, Brown L, Barr IG. Susceptibility of highly pathogenic A(H5N1) avian influenza viruses to the neuraminidase inhibitors and adamantanes. Antiviral Res. 2007;73:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.WHO. [Accessed 7 August 2011];Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to WHO. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2011_06_22/en/index.html.

- 56.Le QM, Kiso M, Someya K, Sakai YT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen KH, Pham ND, Ngyen HH, Yamada S, Muramoto Y, et al. Avian flu: Isolation of drug-resistant H5N1 virus. Nature. 2005;437:1108. doi: 10.1038/4371108a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Jong MD, Tran TT, Truong HK, Vo MH, Smith GJ, Nguyen VC, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Do QH, Guan Y, et al. Oseltamivir resistance during treatment of influenza A(H5N1) infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2667–2672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Earhart KC, Elsayed NM, Saad MD, Gubareva LV, Nayel A, Deyde VM, Abdelsattar A, Abdelghani AS, Boynton BR, Mansour MM, et al. Oseltamivir resistance mutation N294S in human influenza A(H5N1) virus in Egypt. J Infect Public Health. 2009;2:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59*.Kiso M, Takahashi K, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Shinya K, Sakabe S, Le QM, Ozawa M, Furuta Y, Kawaoka Y. T-705 (favipiravir) activity against lethal H5N1 influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:882–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909603107. This paper is the first to show that infection with oseltamivir-resistant highly pathogenic influenza H5N1 viruses can be controlled by T-705, a novel antiviral that is in phase II clinical trials in the United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Govorkova EA, Ilyushina NA, Marathe BM, McClaren JL, Webster RG. Competitive fitness of oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses in a ferret model. J Virol. 2010;84:8042–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00689-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiso M, Kubo S, Ozawa M, Le QM, Nidom CA, Yamashita M, Kawaoka Y. Efficacy of the new neuraminidase inhibitor CS-8958 against H5N1 influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000786. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ilyushina NA, Seiler JP, Rehg JE, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Effect of neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant mutations on pathogenicity of clade 2.2 A/Turkey/15/06 (H5N1) influenza virus in ferrets. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000933. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiso M, Ozawa M, Le MT, Imai H, Takahashi K, Kakugawa S, Noda T, Horimoto T, Kawaoka Y. Effect of an asparagine-to-serine mutation at position 294 in neuraminidase on the pathogenicity of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus. J Virol. 2011;85:4667–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00047-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]