Abstract

Objective

There is little evidence whether sudden cardiac death (SCD) is increasing in Asia, although the incidence of coronary heart disease among urban middle-aged Japanese men has increased recently. We examined trends in the incidence of SCD and its risk factors in the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study.

Design and setting

This was a population-based longitudinal study. Surveillance of men and women for SCD incidence and risk factors was conducted from 1981 to 2005.

Subjects

The surveyed population was all men and women aged 30–84 years who lived in three rural communities and one urban community in Japan.

Main outcome measures

Trends in SCD incidence and its risk factors.

Results

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of SCD decreased from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995, and plateaued thereafter. The annual incidence per 100 000 person-years was 76.0 in 1981–1985, 57.9 in 1986–1990, 39.3 in 1991–1995, 31.6 in 1996–2000 and 36.8 in 2001–2005. The prevalence of hypertension decreased from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995, and plateaued thereafter for men and women. The age-adjusted prevalence of current smoking for men decreased while that of diabetes mellitus increased for both sexes from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005.

Conclusions

The incidence of SCD decreased from 1981 to 1995 but was unchanged from 1996 to 2005. Continuous surveillance is necessary to clarify future trends in SCD in Japan because of an increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus.

Article summary

Article focus

The incidence of coronary heart disease among urban middle-aged Japanese men increased from the 1990s to the 2000s, therefore the incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) may have increased in recent decades.

This is the first study to examine recent trends in SCD in Japan.

Key messages

The age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of SCD among men and women aged 30–84 years in four Japanese communities decreased from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995 and plateaued after 1996.

Continuous surveillance is necessary to clarify future trends in SCD in Japan because of an increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Trends in SCD were analysed using population-based data from a large number of participants in a long-term observational study and annual cardiovascular risk factor surveys ascertained the trends in predisposing risk factors of SCD.

The incidence of SCD was only examined for people aged 30–84 years; other age ranges were not included.

Clinical features and neuroimaging reports were used to exclude death due to stroke; some cases may have been misclassified, especially out-of-hospital deaths.

In the USA, estimates of the annual number of sudden cardiac deaths (SCDs) range from 184 000 to 400 000, accounting for almost half of all coronary heart disease (CHD) deaths.1–4 The incidence of SCD was 50% higher in men than women, and the age-adjusted annual incidence of SCD among US residents aged ≥35 years in 1998 was 410.6 per 100 000 for men and 274.6 per 100 000 for women.3 Several population-based studies have reported the incidence of SCD in Japanese adults,5–8 however these studies are questionable due to methodological problems, such as small sample size,7 a working population8 and an inaccurate definition of SCD based on death certificate data only.6 Baba et al reported that in Suita City (census population: approximately 340 000), the incidence of SCD was 31 (men=45, women=20) per 100 000 people in a sample aged 20–74 years. Information on SCD was determined using police records.5 These findings suggest that the incidence of SCD in Japan is about one-fifth of that in the USA.1 3 9

SCD is generally considered to be caused by CHD. The CHD mortality rate in Japan has been observed to be one-third to one-fifth of that in the USA.6 9 10 This difference might explain the variation in the incidence of SCD between Japan and the USA. However, Kitamura et al reported a significant increase in the incidence of CHD among middle-aged urban Japanese men from 1980–1987 to 1996–2003.11 Therefore, the incidence of SCD for Japanese individuals may have increased in recent decades. So far, no epidemiological study has been reported which has investigated trends in the incidence of SCD in a large population-based study.

The purpose of this study was to examine trends in the incidence of SCD and its risk factors in the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS), a longitudinal community-based study of Japanese men and women.

Methods

The CIRCS is a population-based study of cardiovascular risk factors, disease incidence and their respective trends in Japanese communities (Appendix 1). Details of the study design and procedures have been reported elsewhere.11–14 Briefly, the subjects were Japanese men and women who lived in a north-eastern rural community, Ikawa, a south-western rural community, Noichi, a central rural community, Kyowa and a south-western urban suburb, the Minami-Takayasu district of Yao. Annual cardiovascular risk surveys have been conducted since 1963 in the district of Yao City and Ikawa, since 1969 in Noichi and since 1981 in Kyowa by a joint research team from the Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion, the University of Tsukuba, and Osaka University. In Ikawa, the census population for the age range 30–84 years was 3983 in 1985, 4166 in 1995 and 4173 in 2000. The corresponding population figures for the other communities were 12 940, 14 170 and 14 825 in Yao; 81 49, 10 772 and 10 573 in Noichi; and 96 14, 9 590 and 10 948 in Kyowa.

Informed consent was obtained from community representatives to conduct an epidemiological study based on guidelines established by the Council for International Organisations of Medical Science.15 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion.

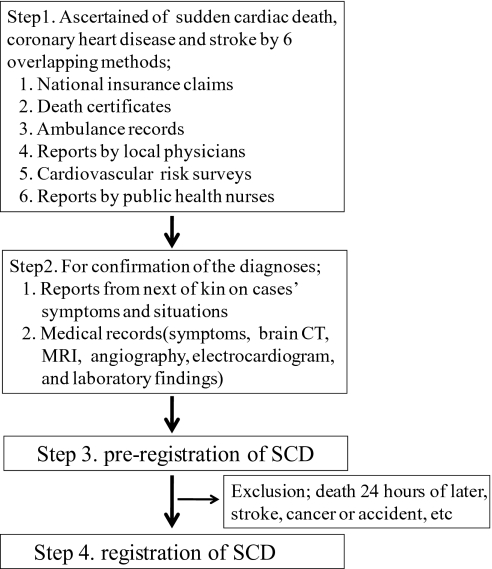

The study included all SCD events that occurred among all residents between 1 January 1981 and 31 December 2005. CHD and SCD events were ascertained from national insurance claims, reports by local physicians, ambulance records, death certificates, reports by public health nurses and health volunteers, and annual cardiovascular risk surveys (figure 1).11–14 Subjects who had moved away from the community or died were treated as censored cases. For confirmation of diagnosis, we also obtained histories from next of kin and reviewed medical records in local hospitals.

Figure 1.

Determination of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

CHD criteria were modified from those of the WHO Expert Committee.16 The indication for definite myocardial infarction (MI) was typical, severe chest pain (lasting at least 30 min and without a definite non-ischaemic cause) accompanied by new, abnormal and persistent Q or QS waves, consistent changes in cardiac enzyme levels or both. If the electrocardiographic and enzyme levels were non-diagnostic or unavailable, but the patient suffered typical chest pain, a diagnosis of possible MI was made. For our study, definite and possible infarctions were combined into a single category, MI. These criteria are essentially the same as those of the WHO Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA) project.17 Angina pectoris was defined as repeated episodes of chest pain during effort, usually disappearing rapidly after the cessation of effort or upon use of sublingual nitroglycerine.12 13 In the present study, CHD included definite or probable MI and angina pectoris.

SCD was defined as sudden unexpected death either within 1 h of symptom onset or within 24 h of having been observed alive and symptom free. We excluded candidate cases if they survived for over 24 h after symptom onset or if there was another apparent cause of death, such as stroke, cancer or accident. The final diagnosis of SCD was made by a panel of three or four trained physician epidemiologists, blinded to the data of cardiovascular risk factors. We further classified the SCD cases into two groups according to the presence or absence of MI.18 If the SCD case was accompanied by MI, it grouped SCD with MI (SCD_MI), and others were grouped as SCD without MI (SCD_NMI). In addition, SCD cases were divided into two groups stratified by time of symptom onset. If the time of symptom onset was within 1 h, they were categorised as SCD1, and if it occurred within 24 h but they were not SCD1, they were categorised as SCD1-24. Finally, SCD cases were divided into two groups based on place of death.3 If the place of death was in an emergency room (ER) or a hospital, the case was categorised as SCD_ER, and if it was outside of a hospital, it was categorised as SCD_NER (table 1).

Table 1.

Trends in age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of sudden cardiac death per 100 000 person-years (and 95% CIs) among men and women aged 30–84 years in four Japanese communities from 1981 to 2005

| 1981–1985 | 1986–1990 | 1991–1995 | 1996–2000 | 2001–2005 | p for trend | |

| Total | ||||||

| Population | 31 754 | 34 686 | 36 717 | 38 698 | 40 519 | |

| Cases | 114 | 101 | 83 | 76 | 97 | |

| Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence | 76.0 (44.8 to 107.2) | 57.9 (32.7 to 83.1) | 39.3 (20.3 to 58.3) | 31.6 (15.6 to 47.6) | 36.8 (19.8 to 53.8) | <0.01 |

| Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence | ||||||

| 30–64 years | 24.1 (4.8 to 43.4) | 19.7 (3.3 to 36.1) | 15.7 (1.8 to 29.6) | 12.4 (0.7 to 24.1) | 17.0 (2.5 to 31.5) | 0.266 |

| 65–74 years | 217.1 (64.9 to 369.3) | 100.2 (1.7 to 198.7) | 99.7 (8.6 to 190.8) | 83.8 (8.9 to 158.7) | 101.8 (24.1 to 179.5) | <0.01 |

| 75–84 years | 541.0 (187.9 to 894.1) | 527.2 (210.6 to 843.8) | 258.5 (67.2 to 449.8) | 204.3 (39.5 to 369.1) | 190.8 (51.1 to 330.5) | <0.01 |

| 40–74 years | 65.0 (29.9 to 100.1) | 40.0 (14.1 to 65.9) | 34.6 (12.2 to 57.0) | 28.8 (10.0 to 47.6) | 33.4 (13.5 to 53.3) | <0.01 |

| Men | ||||||

| Population | 15 048 | 16 471 | 17 421 | 18 422 | 19 306 | |

| Cases | 70 | 61 | 49 | 50 | 67 | |

| Age-adjusted incidence | 111.7 (53.1 to 170.3) | 82.1 (36.0 to 128.2) | 54.4 (20.2 to 88.6) | 49.3 (18.6 to 80.0) | 57.9 (26.2 to 89.6) | <0.01 |

| Women | ||||||

| Population | 16 706 | 18 215 | 19 296 | 20 276 | 21 213 | |

| Cases | 44 | 40 | 34 | 26 | 30 | |

| Age-adjusted incidence | 50.6 (17.1 to 84.1) | 39.5 (12.0 to 67.0) | 27.1 (6.3 to 47.9) | 16.7 (2.0 to 31.4) | 18.2 (2.5 to 33.9) | <0.01 |

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted annual incidence of SCD was calculated from the number of new cases per 100 000 person-years during the periods 1981–1985, 1986–1990, 1991–1995, 1996–2000 and 2001–2005 in the four Japanese communities studied. The rate of moving out from the community during these periods was 2.1%, 3.1%, 2.8%, 2.9% and 1.9%, respectively. In this study, all analyses were limited to men and women aged 30–84 years because the number of SCDs in people aged <30 years was too small (<1%) and for many cases aged ≥85 years, causes of death were difficult to identify.

Cardiovascular risk factors were determined from residents of the four communities in risk factor surveys during each of the five study periods. The surveys were conducted to promote primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The participation rate among the census population in each survey period was 41.9%, 36.8%, 37.1%, 34.8% and 32.0%, respectively. When the age of participants was restricted to 40–74 years, the participation rate was 57.2%, 48.2%, 44.2%, 40.1% and 35.4%, respectively. The participation rate for the age group 40–74 years in Ikawa and Kyowa (with high participation rates) was 73.9%, 62.7%, 61.1%, 57.3%, and 53.6%, respectively, while that in Yao and Noichi (with lower participation rates) was 45.3%, 38.8%, 33.6%, 29.4% and 26.1%, respectively. If people participated in the risk factor survey more than once during each survey period, we used the data from the earliest year.

The items examined in the risk factor surveys included medical history, measurement of total cholesterol, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), blood glucose, ECG findings, and drinking and smoking habits.11 Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, or use of an antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting glucose level ≥7.00 mmol/litre, a non-fasting glucose level ≥11.10 mmol/litre or use of an antidiabetic medication. Overweight was defined as a BMI ≥25 kg/m2. ECG data were obtained with the person in the supine position and were coded with the Minnesota Code, second version,19 by trained physician epidemiologists.

To calculate age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence, we employed the direct standardisation method using the age and sex distributions of the Japanese national model population from 1985 as the standard population. Linear trends in incidence were examined with the χ2 test. We calculated 95% CIs using the following equation:

where N is the standard population for the 5-year age category i, p is the crude incidence of the population for age category i, and n is the number of the population for age category i. Sex-specific age-adjusted means of risk factors were estimated by analysis of covariance, and age-adjusted prevalence by the direct method of standardisation.

The significance of risk factor trends was examined for continuous variables by using the regression analysis for repeated measures,11 with the five periods represented as 1982.5, 1987.5, 1992.5, 1997.5 and 2002.5, and for discrete variables by using the χ2 test for trends. All statistical analyses were performed with the SAS System for Windows (V.9.1).

Results

In this study, 471 people with SCD were identified over 25 years, consisting of 117 SCD_MI and 354 SCD_NMI, 163 SCD1 and 308 SCD1-24, 190 SCD_NER, and 281 SCD_ER. The number of SCDs (in parentheses, SCD_MI) was presented according to the time of symptom onset and the place of death (online supplemental table 1).

As shown in table 1, age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of SCD decreased from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995, however the rate plateaued after 1996 (p for trend <0.01 from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995 and p=0.73 from 1991–1995 to 2001–2005). The annual incidence (95% CI) of SCD per 100 000 person-years during the five periods were 76.0 (44.8 to 107.2), 57.9 (32.7 to 83.1), 39.3 (20.3 to 58.3), 31.6 (15.6 to 47.6) and 36.8 (19.8 to 53.8), respectively. A total of 731 individuals with CHD were identified over 25 years: 256 with definite MI, 254 with probable MI and 221 with angina pectoris, and the number of CHD deaths was 178. The features of the SCD trends for the age groups 30–64, 65–74 and also 40–74 were similar to those of the overall trend, while there was a constant decline in the SCD incidence for age group 75–84.

A similar trend was observed for age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of CHD. The annual incidence (95% CI) of CHD per 100 000 person-years was 98.2 (62.7 to 133.7), 87.0 (56.0 to 118.0), 78.0 (50.9 to 105.1), 50.0 (29.8 to 70.2) and 57.5 (36.5 to 78.5), respectively. A slightly different trend was observed for MI. The annual incidence (95% CI) of MI per 100 000 person-years was 55.2 (28.6 to 81.8), 58.9 (33.4 to 84.4), 57.5 (34.4 to 80.6), 34.6 (17.9 to 51.3) and 45.6 (26.9 to 64.3) (data not shown in table 1).

The incidence of SCD was two to three times higher for men than for women, while age-adjusted annual incidence (95% CI) of SCD per 100 000 person-years during the five time periods was 111.7 (53.1 to 170.3), 82.1 (36.0 to 128.2), 54.4 (20.2 to 88.6), 49.3 (18.6 to 80.0) and 57.9 (26.2 to 89.6) for men and 50.6 (17.1 to 84.1), 39.5 (12.0 to 67.0), 27.1 (6.3 to 47.9), 16.7 (2.0 to 31.4) and 18.2 (2.5 to 33.9) for women (table 1).

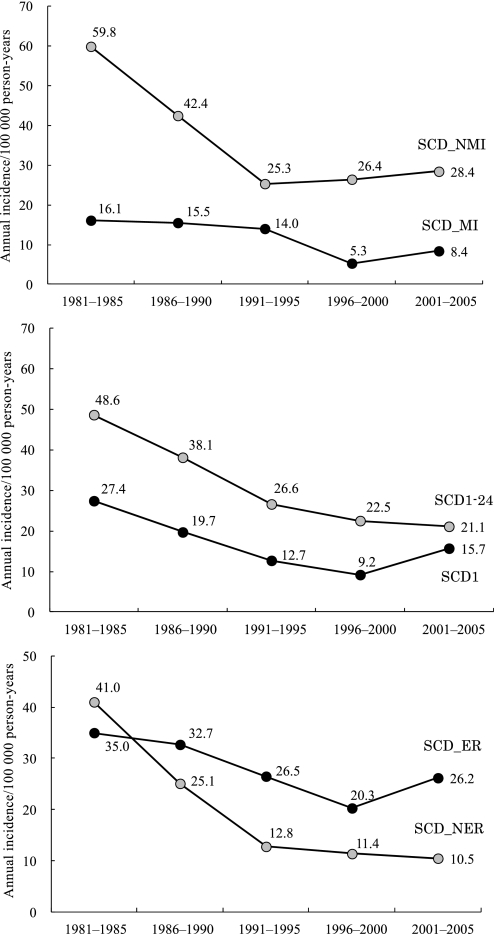

We further analysed the incidence of SCD stratified by the presence or absence of MI, the time of symptom onset and the place of death (figure 2). The age-adjusted and sex-adjusted annual incidence (95% CI) of SCD per 100 000 person-years was 16.1 (1.7 to 30.5), 15.5 (2.4 to 28.6), 14.0 (2.7 to 25.3), 5.3 (0 to 11.7) and 8.4 (0.3 to 16.5) for SCD_MI and 59.8 (32.1 to 87.5), 42.4 (20.8 to 64.0), 25.3 (10.0 to 40.6), 26.4 (11.7 to 41.1) and 28.4 (13.4 to 43.4) for SCD_NMI. The calculation of the incidence stratified by the time of symptom onset yielded age-adjusted and sex-adjusted annual incidence (95% CI) per 100 000 person-years of 27.4 (8.6 to 46.2), 19.7 (4.9 to 34.5), 12.7 (1.9 to 23.5), 9.2 (0.3 to 18.1) and 15.7 (4.4 to 27.0) for SCD1, and 48.6 (23.7 to 73.5), 38.1 (17.7 to 58.5), 26.6 (10.9 to 42.3), 22.5 (9.1 to 35.9) and 21.1 (8.4 to 33.8) for SCD1-24. The calculation of the incidence stratified by the place of death yielded the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted annual incidence (95% CI) per 100 000 person-years of 41.0 (18.0 to 64.0), 25.1 (8.5 to 41.7), 12.8 (2.1 to 23.5), 11.4 (1.9 to 20.9) and 10.5 (1.7 to 19.3) for SCD_NER, and 35.0 (13.9 to 56.1), 32.7 (13.7 to 51.7), 26.5 (10.7 to 42.3), 20.3 (7.3 to 33.1) and 26.2 (11.6 to 40.8) for SCD_ER. These trends showed similar features to those of the overall trend.

Figure 2.

Trends in age-adjusted and sex-adjusted annual incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD), stratified by the presence or absence of myocardial infarction (MI), the time of symptom onset and the place of death. Annual incidence per 100 000 among men and women aged 30–84 in four Japanese communities from 1981 to 2005: SCD with MI (SCD_MI) and SCD without MI (SCD_NMI), SCD within 1 h (SCD1) and SCD between 1 and 24 h (SCD1-24), SCD in an emergency room or a hospital (SCD_ER) and SCD outside of a hospital (SCD_NER).

We estimated the national SCD incidence in 2009 by using the results from this study. For this estimation, we multiplied the age-specific and sex-specific populations in 2009 by the age-specific and sex-specific incidences of SCD from 2001 to 2005. For the population aged 85 years or over, we used the incidence of SCD for ages 75–84 years. We predicted the number of cases of SCD in Japan to be at least 51 700 cases in 2009.

As shown in table 2, the overall trends in risk factors of SCD showed the same features for men and women, except for diastolic BP, BMI, current smoking and heavy drinking. Mean diastolic BP for women decreased from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005 (p for trend was <0.01), whereas that for men was constant from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995, but increased after 1996 (p for trend was <0.01). For men and women, mean systolic BP decreased from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005 (p for trend was <0.01). The prevalence of hypertension decreased from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995, but plateaued after 1996 in both sexes. The mean BMI for women declined from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005 (p for trend was <0.01), whereas BMI for men increased. The prevalence of current smoking and heavy drinking decreased constantly from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005 (p for trend was <0.01, for both) for men but did not change for women. Mean levels of total cholesterol, and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus increased continuously from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005 (p for trend was <0.01, for both sexes). The prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy dramatically decreased from 1981–1985 to 2001–2005 (p for trend was <0.01, in both sexes). Additionally, we examined the risk factor trends in ages 40–74 years (online supplemental table 2), and also stratified by community (Ikawa and Kyowa: online supplemental table 3/Yao and Noichi: online supplemental table 4), and found the same trends.

Table 2.

Trends in age-adjusted and sex-adjusted cardiovascular risk factors among men and women aged 30–84 years in four Japanese communities from 1981 to 2005

| 1981–1985 | 1986–1990 | 1991–1995 | 1996–2000 | 2001–2005 | p for trend | |

| Men | ||||||

| N | 5350 | 4992 | 5175 | 5039 | 4900 | |

| Age, years | 55 | 56 | 58 | 59 | 60 | |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 137 | 134 | 133 | 134 | 133 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 81 | 81 | 81 | 82 | 82 | <0.01 |

| Antihypertensive medication, % | 19.8 | 18.6 | 17.2 | 18.0 | 20.1 | 0.550 |

| Hypertension, % | 49.2 | 44.1 | 41.3 | 44.7 | 44.6 | <0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.7 | 22.9 | 23.3 | 23.5 | 23.8 | <0.01 |

| Overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), % | 26.2 | 29.2 | 29.6 | 33.5 | 34.7 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/litre | 4.75 | 4.89 | 4.98 | 5.13 | 5.23 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol ≥5.69 mmol/litre, % | 14.0 | 17.7 | 20.7 | 26.8 | 31.4 | <0.01 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/litre | 63.0 | 69.7 | 67.7 | 63.0 | 61.1 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 3.8 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 9.7 | <0.01 |

| Heavy drinking (ethanol intake ≥46 g/day), % | 33.4 | 29.8 | 28.3 | 27.5 | 23.1 | <0.01 |

| Current smoking, % | 60.1 | 55.8 | 52.6 | 49.5 | 44.6 | <0.01 |

| ECG findings, % | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.731 |

| Ventricular premature contraction | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.039 |

| Supraventricular premature contraction | 3.3 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 0.547 |

| Major ST-T abnormality | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 0.109 |

| Minor ST-T abnormality | 12.5 | 10.1 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 0.871 |

| PQ prolonged | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.298 |

| Complete/incomplete right bundle | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 6.7 | <0.01 |

| Wide QRS | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.1 | <0.01 |

| Abnormal Q wave | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.431 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 29.1 | 27.5 | 22.5 | 19.2 | 17.3 | <0.01 |

| Women | ||||||

| N | 7949 | 7781 | 8463 | 8436 | 8082 | |

| Age, years | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 134 | 132 | 130 | 130 | 128 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 79 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 77 | <0.01 |

| Antihypertensive medication, % | 19.2 | 18.4 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 18.1 | <0.01 |

| Hypertension, % | 42.0 | 37.1 | 34.0 | 34.9 | 33.6 | <0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.5 | 23.4 | 23.3 | 23.3 | 23.2 | <0.01 |

| Overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), % | 34.4 | 33.4 | 31.1 | 30.9 | 28.0 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/litre | 5.09 | 5.24 | 5.27 | 5.44 | 5.49 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol ≥5.69 mmol/litre, % | 24.7 | 29.3 | 31.1 | 39.7 | 44.7 | <0.01 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/litre | 58.3 | 65.2 | 62.6 | 57.2 | 56.5 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 2.1 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.4 | <0.01 |

| Heavy drinking (ethanol intake ≥46 g/day), % | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.109 |

| Current smoking, % | 6.3 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 7.1 | <0.01 |

| ECG findings, % | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | <0.01 |

| Ventricular premature contraction | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.825 |

| Supraventricular premature contraction | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.316 |

| Major ST-T abnormality | 6.5 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.8 | <0.01 |

| Minor ST-T abnormality | 21.9 | 18.6 | 19.8 | 19.5 | 17.5 | <0.01 |

| PQ prolonged | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.212 |

| Complete/incomplete right bundle | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 0.099 |

| Wide QRS | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.751 |

| Abnormal Q wave | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.015 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 11.1 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 6.0 | 4.9 | <0.01 |

Data are mean values or percentages.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure.

Discussion

In this longitudinal community-based study from 1981 to 2005, we found that the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted annual incidence of SCD decreased from 1981 to 1995 and plateaued thereafter. This trend was similarly observed when SCD was stratified according to the following factors: presence of MI, with MI constituting approximately 20–35% of all SCDs; time of symptom onset, with SCD within 1 h constituting approximately 30–45% of all SCDs; and place of death, with SCD in the emergency room or hospital constituting approximately 4–70% of all SCDs. Although the incidence of SCD was higher for men than for women, which is consistent with previous reports,3 20 trends in the incidence of SCD did not vary according to age or sex. Since Japan is a rapidly ageing country, the number of SCDs in Japan, although much lower than in the USA,3 may increase in the future due to an increased older population.

Several population-based studies have previously reported the incidence of SCD among the Japanese population. The Hisayama study reported that the age-adjusted annual incidence rate of SCD between 1988 and 2000 was 76 per 100 000 person-years for men and 19 per 100 000 person-years for women aged 40 and over, and that the incidence rate did not change during the study period. However, the size of this population sample was 1110 for men and 1527 for women, which made it difficult to evaluate trends in the incidence of SCD.7 Baba et al reported that the annual SCD incidence in people aged 20–74 years in Suita City in 1992 was 45 per 100 000 for men and 20 per 100 000 for women.5 Our study showed a similar age-adjusted annual incidence of SCD (57.9 per 100 000 person-years for men and 18.2 per 100 000 person-years for women aged 30–84 years) in 2001–2005.

In Western countries, SCD accounts for almost half of all CHD deaths,2 21 while CHD accounted for at least 80% of all SCD cases.22 In this study, SCD accounts for 10% of all CHD deaths, while CHD accounted for 25% of all SCD cases, which was generally consistent with the findings from a previous Japanese population-based study.20 The lower incidence11 and mortality rates9 10 23 from CHD in Japan than in the USA probably correspond to the lower incidence of SCD in Japan.

Several population-based studies have reported the age-adjusted annual incidence of MI among Japanese men and women24–26: 42.3 per 100 000 person-years for age 20 years and over in 1988–1998,24 45.8 per 100 000 person-years for the age range 35–64 years in 1994–1996,25 and 49.7 per 100 000 person-years for age 20 years and over in 1996–1998.26 In this study, the age- adjusted and sex- adjusted annual incidence of MI for the age range 30–84 years was 34.6–58.9 per 100 000 person-years in 1981–2005. These findings confirm the low incidence of CHD in Japan. However, Rumana et al reported that the incidence of acute MI increased from 1990–1992 to 1999–2001 in the Takashima AMI Registry.26 Furthermore, Kitamura et al reported a significant increase in the incidence of CHD from 1980–1987 to 1996–2003 for middle-aged men in an urban community,11 which was involved in this CIRCS. Because the prevalence of overweight and diabetes mellitus has increased during the last two decades as seen in our study and other Japanese studies,9 11 27 the incidence of SCD might increase in the future.

The data presented here show that the incidence of SCD_ER decreased from 1981 to 1995, but plateaued after 1996, whereas the incidence of SCD_NER has decreased steadily over time. The plateauing trend of SCD_ER may be due to the doubling of the number of patients transported to emergency rooms by ambulance between 1996 and 2006.28

Risk factors for SCD among Americans have been identified as hypertension, hypertensive organic change, older age, male sex, smoking, heavy drinking, overweight, diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy.3 Hypertension, current smoking and diabetes mellitus were found to be potential risk factors for SCD among the Japanese population.20 29 In this study, the SCD incidence decreased from 1981 to 1995 when a reduction in the prevalence of hypertension and current smoking was observed. The SCD incidence remained unchanged from 1996 to 2005 when the prevalence of hypertension was unchanged, the prevalence of current smoking decreased and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus increased.

This study has the following strengths. We analysed trends in SCD using population-based data, including urban and rural areas, from a large number of participants in a long-term observational study. The cause of death from death certificates was validated by medical records and/or information from next of kin. In addition, annual cardiovascular risk factor surveys ascertained the trends in predisposing risk factors of SCD.

Nonetheless, our study has a few limitations. First, we only examined the incidence of SCD for the age range 30–84 years. However the frequency of SCD among people <30 years old was found to be <1% even in the USA,3 so this age window is unlikely to substantially affect the results. Second, although clinical features and neuroimaging reports were used to exclude death due to stroke, some cases may have been misclassified, especially out-of-hospital deaths. Such misclassifications may well have affected the changes in the incidence of SCD that occurred out of hospital. Third, since we did not include cases of resuscitated SCDs for over 24 h after symptom onset, the true incidence of SCD might be underestimated. However, the magnitude of underestimation should be small because the annual number of resuscitated cardiac arrest cases in our surveyed population was only around 0.7 based on the 2003 statistics of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency.30

In conclusion, age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of SCD for a general Japanese population decreased from 1981–1985 to 1991–1995 and plateaued after 1996, when a reduction in the prevalence of hypertension and current smoking was observed. Continuous surveillance is necessary to clarify future trends in SCD in Japan because of an increasing trend for diabetes mellitus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, staff and the participants of the CIRCS for their valuable contributions. We acknowledge Drs Hiromichi Kimura, Sachiko Masuda and Toshihiko Yamada, University of Tokyo, and Dr Koji Tachikawa, University of Nagoya for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

Appendix 1. CIRCS study collaborators

The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS) is a collaborative study managed by the Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion, University of Tsukuba, Osaka University and Ehime University. The following CIRCS investigators contributed to this study: Masamitsu Konishi, Yoshinori Ishikawa, Akihiko Kitamura, Masahiko Kiyama, Takeo Okada, Kenji Maeda, Masakazu Nakamura MD, Masatoshi Ido, Masakazu Nakamura PhD, Takashi Shimamoto, Minoru Iida and Yoshio Komachi, Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion, Osaka; Yoshihiko Naito, Mukogawa Women's University, Nishinomiya; Tomonori Okamura, Keio University, Tokyo; Shinichi Sato, Chiba Prefectural Institute of Public Health, Chiba; Tomoko Sankai, Kazumasa Yamagishi, Kyoko Kirii, ChoyLye Chei, Kimiko Yokota and Minako Tabata, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba; Mitsumasa Umesawa, Ibaraki Prefectural University of Health Sciences, Inashiki; Hiroyasu Iso, Tetsuya Ohira, Renzhe Cui, Hironori Imano, Ai Ikeda, Satoyo Ikehara, Isao Muraki and Minako Maruyama, Osaka University, Suita; Takeshi Tanigawa, Isao Saito, Katsutoshi Okada and Susumu Sakurai, Ehime University, Toon; Masayuki Yao, Ranryoen Hospital, Ibaraki; and Hiroyuki Noda, Osaka University Hospital, Suita, Ai Ikeda, National Cancer Center, Tokyo.

Footnotes

To cite: Maruyama M, Ohira T, Imano H, et al. Trends in sudden cardiac death and its risk factors in Japan from 1981 to 2005: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). BMJ Open 2012;2:e000573. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000573

Contributors: Minako Maruyama analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and provided statistical expertise. Akihiko Kitamura, Masahiko Kiyama, Takeo Okada, Kenji Maeda, Yoshinori Ishikawa and Takashi Shimamoto acquired the data and critically revised the manuscript. Tetsuya Ohira, Hironori Imano, Hiroyuki Noda, Kazumasa Yamagishi and Hiroyasu Iso conceived and designed the study, acquired and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported in part by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (grant-in-aid for research C: 21590731).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Osaka Medical Center for Health Science and Promotion.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data.

References

- 1.Chugh SS, Jui J, Gunson K, et al. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death certificate-based review in a large U.S. community. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:1268–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Castellanos A. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology, transient risk, and intervention assessment. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:1187–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, et al. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation 2001;104:2158–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adabag AS, Lueqker RV, Roger VL, et al. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:216–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba S, Konishi M, Asano G, et al. Survey of sudden cardiac death for the complete medical recode in a large city—consider the frequency and underlying and background factor in Japanese. JACD. 1996;31:100–6 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toyoshima H, Hayashi S, Tanabe N, et al. Estimation of the proportional rate of ischemic heart disease in sudden death from death certificate and registration surveys in Niigata prefecture in Japanese. JACD 1996;31:93–9 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubo M, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, et al. Trends in the incidence, mortality, and survival rate of cardiovascular disease in a Japanese community: the Hisayama Study. Stroke 2003;34:2349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura T, Kondo H, Hirai M, et al. Sudden death in the working population. A collaborative study in central Japan. Eur Heart J 1999;20:338–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iso H. Changes in coronary heart disease risk among Japanese. Circulation 2008;118:2725–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baba S, Ozawa H, Sakai Y, et al. Heart disease deaths in a Japanese urban area evaluated by clinical and police records. Circulation 1994;89:109–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura A, Sato S, Kiyama M, et al. Trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease and stroke and their risk factors in Japan, 1964 to 2003. The Akita-Osaka Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:71–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimamoto T, Komachi Y, Inaba H, et al. Trends for coronary heart disease and stroke and their risk factors in Japan. Circulation 1989;79:503–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura A, Iso H, Iida M, et al. Trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease and stroke and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among Japanese men from 1963 to 1994. Am J Med 2002;112:104–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imano H, Kitamura A, Sato S, et al. Trends for blood pressure and its contribution to stroke incidence in the middle-aged Japanese population. The Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Stroke 2009;40:1571–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International guidelines for ethical review of epidemiological studies. Law Med Health Care 1991;19:247–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Expert Committee. Arterial Hypertension and Ischemic Heart Disease, Preventive Aspects. WHO Technical Report Series No 231. Geneva: WHO, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, et al. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration Procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation 1994;90;583–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannel WB, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, et al. Sudden coronary death in women. Am Heart J 1998;136:205–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Kornitzer M, et al. Prognostic value of ECG findings for total, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease death in men and women. Heart 1998;80:570–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanabe N, Toyoshima H, Hayashi S, et al. Epidemiology of sudden death in Japan (In Japanese). Jpn J Electrocardiol 2006;26:111–17 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox CS, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Temporal trends in coronary heart disease mortality and sudden cardiac death from 1950 to 1999: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004;110:522–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myerburg RJ. Sudden cardiac death: exploring the limits of our knowledge. J Cadiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12:369–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito I, Folsom AR, Aono H, et al. Comparison of fatal coronary heart disease occurrence based on population surveys in Japan and the USA. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:837–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida M, Yoshikuni K, Nakamura Y, et al. Incidence of acute myocardial infarction in Takashima, Shiga, Japan. Circ J 2005;69:404–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanabe N, Saito R, Sato T, et al. Event rates of acute myocardial infarction and coronary death in Niigata and Nagaoka cities in Japan. Circ J 2003;67:40–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rumana N, Kita Y, Turin TC, et al. Trend of increase in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction in a Japanese population. Takashima AMI registry, 1990–2001. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:1358–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam MM, Horibe H, Kobayashi F. Current trend in prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Japan, 1964–1992. J Epidemiol 1999;9:155–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fire and Disaster Management Agency Current State of Emergency Rescue in Japan 2006. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2008/07/dl/s0717-7c.pdf (accessed 17 Jul 2009).

- 29.Ohira T, Maruyama M, Imano H, et al. Risk Factors for Sudden Cardiac Death among Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Hypertens 2012. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fire and Disaster Management Agency The Effect of ‘Defibrillation’ by Emergency Live-saving Technician. http://www.fdma.go.jp/ugoki/h1604/17.pdf (accessed 1 Feb 2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.